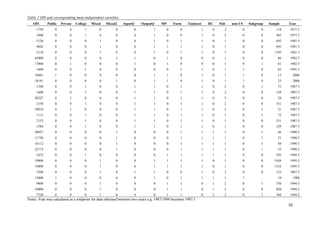

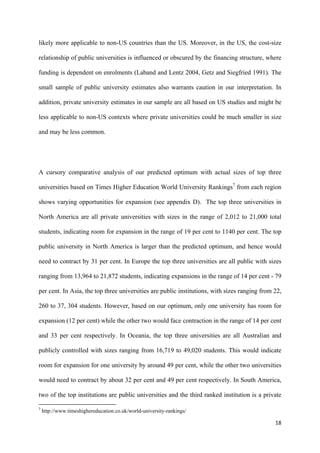

This study uses meta-regression analysis to estimate the optimal size of higher education institutions based on 21 previous studies. It finds an optimal institutional size of 24,954 students. The study also analyzes how institutional characteristics like being a public/private university, US/non-US, and sample size impact the optimal size. It suggests mergers could increase the size of some institution types but cautions that optimal sizes may vary in different contexts.