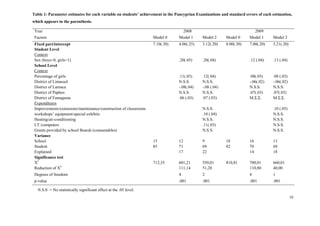

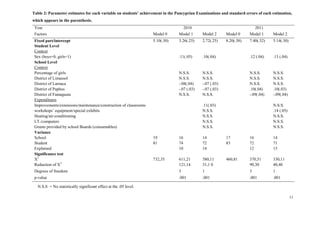

This document summarizes a study that examined the relationship between educational expenditures and student learning outcomes in Cyprus from 2008-2012. The study used multilevel analysis and discriminant function analysis to analyze test score data from over 9,500 secondary school students. The study found that investment in least effective schools had a positive impact on school effectiveness, while investment in specific equipment also improved student outcomes. Gender influenced outcomes but class size did not. The results suggest educational investment can improve school effectiveness and student learning when targeted appropriately.