The document discusses the evolution of the Wonderland platform for European architecture, which fosters collaboration and innovation among emerging architectural practices. It highlights a shift from traditional architectural roles to a focus on participatory interventions, community engagement, and addressing urban challenges through alternative methodologies. Various projects and interviews illustrate the impact of these new practices in reactivating disused spaces and engaging local stakeholders across Europe.

![ACTIVATE & INVOLVE

content

Content

Editorial

2

4

Activate & Involve 8

Reactivate!

12

Mobile Fertile

14

Share & Communicate

18

Architecture for public - Budapest

19

Vacancy - Cluj

22

Social Coherence - Paris

24

The case of ‘The Sea in me‘‘

26

LOCAL SQUARES:

connecting and training participation experts in Europe

28

PLAN E[XTINCTION] 30

Suburban Storytelling

31

Interview with Volkmar Pamer, planning department City of Vienna 32

Test & Intervene

34

The wonderland pavilion - Venice

35

Project Space - Amsterdam

38

The Urban Islands Project 40

Play van Gendthallen! The making of the Freezing Favela

42

Park[haus]

44

Creating ordinary utopia

46

Interview with Stefanie Raab, Coopolis, Berlin 48

Interview with Jesper Koefoed-Melson, givrum.nu, Copenhagen 51

2](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/magazinactivateinvolve-131024085028-phpapp02/85/Wonderland-Magazine-Activate-Involve-2-320.jpg)

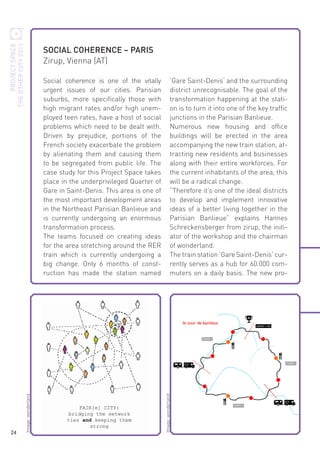

![Interview with Jurgen Hoogendoorn Reactivate!

Indira van ’t Klooster

City of Amsterdam

A10, Amsterdam (NL)

Amsterdam (NL) p. 68

p. 12

De Ceuvel

ACTIVATING URBAN VOIDS 2012

space&matter

PROJECT SPACE AMSTERDAM

placemakers, Amsterdam (NL) p. 38 Amsterdam (NL) p. 64

The Urban Islands

Spacepilots

Aachen (DE) p. 40

Interv

Jespe

Givru

p. 51

Play van Gendthallen!

Play the City

Amsterdam (NL) p. 42

Park[haus]

ACTIVATING URBAN VOIDS

superwondergroup MACH MANN HEIM

Mannheim (DE) p. 44 Mannheim (DE) p. 57

Mobile Fertile

Coloco

Paris (FR) p. 14

THE OTHER CITY 2011

SOCIAL COHERENCE - PARIS

Zirup, Vienna (AT) p. 24

Creating ordinary utopia

Cochenko

Paris (FR) p. 46

THE OTHER CITY 2010

THE WONDERLAND PAVILION – VENICE

celia & Hannes, Montpelier (FR) p. 35

PLAN E[XTINCTION]

PKMN

Madrid (ES) p. 30

6

The V-House

The Milk Train

Rome (IT) p. 62

Int

Co

Be](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/magazinactivateinvolve-131024085028-phpapp02/85/Wonderland-Magazine-Activate-Involve-6-320.jpg)

![PLAN E[XTINCTION]

PKMN Achitectures, Cienfuegos

(ES)

Plan E[xtintion] is a project that searches to link the collective identity of endangered settlements in Asturias with

that of their surviving inhabitants as a

way to stand out depopulation processes, turning the image of these citizens

into the representative image of this

phenomenon.

A pilot project of Plan E[xtintion] took

place in Cienfuegos [Asturias], a rural

settlement were only 10 people still

live permanently. All of the inhabitants

were reunited in an emblematic spot

and a collective portrait of them was taken. This photo has become the symbolic entrance of the village, as it happens

to be with the Osborne Bull or the Welcome to Fabulous Las Vegas entrance

sign. By reusing an obsolete PlanE sign

from the Spanish Economy and Employment Stimulus Plan, formerly used in

Gijón – a city where many of Cienfuegos’ inhabitants moved to live in - the

importance of the people living in these

settlements, which are bound to disappear, was underlined.

The Plan E[xtintion] was initiated in Cienfuegos (Asturias) Spain by the team PKMN [pacman] Architec-

Image: PKMN

tures. For further information: www.pkmn,es

30](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/magazinactivateinvolve-131024085028-phpapp02/85/Wonderland-Magazine-Activate-Involve-30-320.jpg)

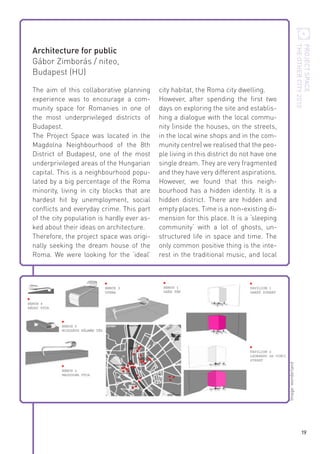

![Suburban storytelling

Onorthodox, Amsterdam (NL)

& Vienna (AT)

collective photo and video exhibition in

Rajka (HU) and a big three-village festivity for which the mayor decided to

close the street to car traffic (a third,

indirect intervention). Nostalgia re-established social ties from the past

and gave space to those who are rarely included in the social and spatial

discourse – the elderly. An in-between

use or action does not necessarily

need to be created by those with an

initial idea. Co-creation and -operation are important tools to enhance and

nurture community life, hence offering

a self-maintaining, resilient condition.

Image: Onorthodox

The sub- and ex-urban cross-border

area of Austria, Hungary and Slovakia is

connected with a common history, culture and languages, however separated

it may be when it comes to social ties.

Nostalgia, an intervention developed

in this area had a physical and social dimension. We used the abandoned

customs duty building, once separating

the countries, as an attractor, an object

of exhibition. The social layer of our

intervention lied in participation and

empowerment. We interviewed about

100 elderly people where we collected

personal stories and photographs from

the past. The intervention ended with a

ONORTHODOX is a young established group of urban researchers from different fields and countries that aim

at tackling urban issues. ONORTHODOX is an open project space founded by Margot Deerenberg [NL] and

Thomas Stini [AT] in 2009 in Amsterdam Vienna. The current project was realised by Margot Deerenberg,

/

Veronika Kovacsova, Thomas Stini. For further information: www.onorthodox.com

31](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/magazinactivateinvolve-131024085028-phpapp02/85/Wonderland-Magazine-Activate-Involve-31-320.jpg)

![Besides a space enabling people to

meet each other, it was decided that

the house should also fulfil the purpose of allowing the broadcasting and

statement of opinions on upcoming decisions. Initially, voting was about what

citizens of the area would like to do or

see if there were to be a public stage in

Amsterdam Noord.

The choice could be made by picking one

of the prepared symbols – from ballet to

bingo – or by drawing something new

on one of the empty papers and pinning

them on the inner wall of the house.

The shelters themselves, as well as the

symbols on color-coded sheets of paper

were prepared in co-operation with the

local students (of the Bredero Lyceum).

The students and architects started in

the early morning hours to finish the

house construction on time.

Applause arose when the house was

finally erected on all four pillars. The

teams were ready for the public intervention on the market square in Waterlandplein / Amsterdam Noord.

Walking to the square while carrying

the house generated a lot of attention.

The infamous Dutch weather also showed signs of mercy, and it stayed dry

throughout the whole intervention.

People were instantly curious about

the neon coloured-walking-house and

were willing to share their opinions.

Following the intervention, the house

looked fully packed with various symbols hanging on the inner walls of the

temporary shelter. It was a great success and helped us obtain valuable information about the needs and wishes

of the residents.

The workshop took place between 15th and 19th October 2012 in Amsterdam in collaboration with placemakers. Participants were SPACEPILOTS, PKMN [pac-man], Elana Bos, Veronika Kovacsova, Mara Pellizzari

Image: wonderland

Image: wonderland

and the Students of the Bredero Lyceum.

39](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/magazinactivateinvolve-131024085028-phpapp02/85/Wonderland-Magazine-Activate-Involve-39-320.jpg)

![THE URBAN ISLANDS PROJECT

SPACEPILOTS, Aachen (DE)

The Urban Islands Project is part of

an on-going project SPACEPILOTS introduced in 2009 under the title of Unlocking the City, aiming to excite young

people about their city, engage them

with their environment, and empower

them to get involved in the actual shaping of places.

We are inviting young people to participate in the research and development of

design ideas for Urban Islands. Therefore, by nature, the testing, analysing, and

constant adjusting of ideas is inherent to

the project and its aims. The resulting

works are interventions, installations, or

actions hinting at a particular potential

of an urban space while – temporarily offering a different use.

In a first phase, prior to the project, a city-wide survey has been run in London

in 2009 asking young people about their

local environment and the interventions

they would like to see put in place to improve their lives. The Urban Islands Project is a direct response to their call to

create places where they can meet each

other and feel safe.

In 2010 we launched the project at the

London Festival of Architecture [LFA

2010], in the Borough of Southwark,

South London. During the LFA 2010 we

have been running a series of workshops with nine young people living in

the area, exploring possible ways to de-

40

tect, map and animate places through

urban interventions and architectural

actions. The youngsters set out scanning the neighbourhood to find overlooked spots and niches in their environment that might allow for an island to

unfold and act – be it as a meeting point,

a playground, a picnic corner…

Within three weeks they built urban

furniture, tested ways of mapping and

learned about the process of designing

in the public realm, planted seeds, created a light garden, exchanged ideas with

various local experts from the fields of

architecture, urban planning and lighting design, and made a documentary

– working with a photographer and filmmaker during the festival events.

In the last 3 years we have been testing

and developing The Urban Islands Project in various collaboration and cultural

contexts in London, Madrid, Bucharest

and Cologne.

The importance of such projects lies, I

think, in direct contrast to traditional architectural work in its limited temporality: as

they exists only for a short period of time,

the before and after appearance, use or

disuse of an area is brought to peoples

attention. This sharpened perception of

their neighbourhood, in return, most often prompts for debate - if not further

actions, and that way establishing the

idea.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/magazinactivateinvolve-131024085028-phpapp02/85/Wonderland-Magazine-Activate-Involve-40-320.jpg)

![Park[haus]

superwondergroup,

Mannheim (DE)

The top floor of the a car park in the city

centre of Stuttgart will be transformed

into a temporary community garden.

The design, realization and programme

is developed collectively with residents,

pupils and interested groups. The programme of the Park[haus] is composed

of urban gardening farming, flower/

beds, a lawn, a small kiosk and a community kitchen. Additionally a cultural

programme including workshops, discussions, film screenings and so on will

be organised by the participants.

The Leonhardsviertel in Stuttgart where

the car park is located is nowadays best

known as the red light district of Stuttgart. Right in front of the parking deck,

prostitution takes place. The neighbourhood is, however, also a residential area,

where you can find some of the oldest

houses in Stuttgart, the Jakobschule –

an elementary school rich in tradition. In

the narrow streets of the old town, some

well-known wine taverns are hidden.

However, the number of the brothels

increased over the last years and the

‘balance‘ of the neighbourhood is threatened. The City of Stuttgart tries to

buy uninhabited houses in order to rent

them, but financial means are limited. A

lot of children and adolescents live there, most of the families have low incomes, and leisure facilities are rare.

44

Stakeholders are:

superwondergroup

Initiator / Planning / Development of the

supporting programme / moderating

workshops & round table discussions /

setting up the 2-year-programme

Ebene 0 e.V.

Co-Initiator and organizer of the project.

The ‘Ebene 0’ is a non-profit art association with a focus on urban topics such as

temporary uses and alternative planning

approaches.

Parkservice Hüfner

Private enterprise, which is the tenant of

the car park and has interests in ‚upgrading‘ the typology of the car park.

Administration of the Neighbourhood /

Mayor of the Neighbourhood

Responsible for regulations and administrative issues. Provided initial financial support as well as a helping hand by

dealing with other departments.

The Project is divided into two phases,

differing mainly in the size of the used

parking space and the uses.

The first phase already started in April

2013 as an urban gardening project, with

around 80 interested citizens, in a sub

area of the top floor of the car park, and

will last until September / October 2013

when the urban garden will be dismantled. This phase is accompanied by a programme consisting of workshops (dea-](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/magazinactivateinvolve-131024085028-phpapp02/85/Wonderland-Magazine-Activate-Involve-44-320.jpg)

![Levente Polyak:

What can you offer the owner, so that

he decreases the price?

Image: Coopolis

Stefanie Raab:

Advice and experience in a special area – this is very important, you always have

to be very local. If we have projects in different places, we always have a project

manager for each one of them, so that the contact between the owners and the

users is enriched by the local knowledge of this person.

In fifty percent of the cases, neither the users nor the owners know what they need

in the beginning. So we have an open door once a week, a consultation process

with the users and also the owners of the real estates. If they [the owners] would

know what they wanted with it, it wouldn’t be empty. You have to find it out and give

them advice.

And if you have an owner who imagines 10 euro/m2 rent, we tell him, that this is

a very poor district here, there will be no activity that can bring so much money.

So you have to talk to him, so that he can also feel that his goals are unrealistic,

because the only reason for emptiness is that there is no market for a product, so

you have to create a market and bring someone who creates this product as well

as someone who needs this product.

50

The interview was conducted in the frame of

the Lakatlan Budapest project, initiated by the

KÉK - Hungarian Contemporary Architecture

Centre.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/magazinactivateinvolve-131024085028-phpapp02/85/Wonderland-Magazine-Activate-Involve-50-320.jpg)