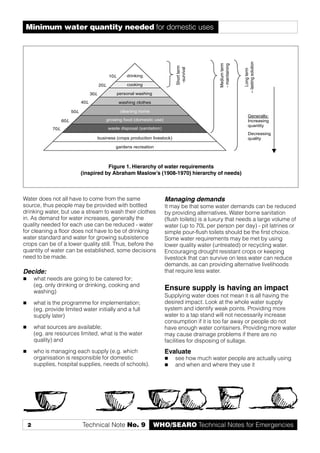

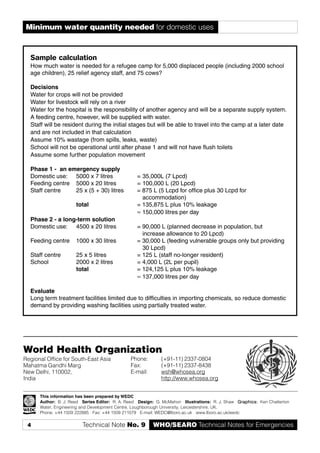

This document provides guidance on estimating water needs and requirements for domestic use after an emergency. It recommends collecting information on the population size and individual water usage. Standard water requirements are provided for drinking, sanitation, cooking, hygiene, and other domestic needs which range from 7 to 50 liters per person per day depending on the situation. Non-potable water sources can be used for some needs. Proper management of water supplies, collection points, storage, and waste disposal is necessary to ensure access to sufficient water.