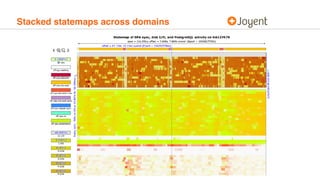

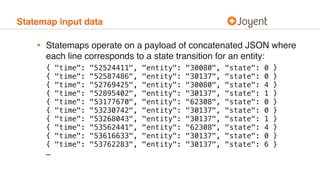

Statemaps provide a visualization of system state over time to help understand performance issues. They show transitions between different states for entities like processes. The statemap output is an interactive SVG that can be zoomed and filtered. Tagged, stacked, and coalesced statemaps provide additional context and correlation across systems. Statemaps are meant to raise questions about performance that can then be answered through system observability tools.

![Statemap input data

• States are described in JSON metadata header, e.g.:

{

"start": [ 1544138397, 322335287 ],

"title": "PostgreSQL statemap on HAB01436, by process ID",

"host": "HAB01436",

"entityKind": "Process",

"states": {

"on-cpu": {"value": 0, "color": "#DAF7A6" },

"off-cpu-waiting": {"value": 1, "color": "#f9f9f9" },

"off-cpu-semop": {"value": 2, "color": "#FF5733" },

"off-cpu-blocked": {"value": 3, "color": "#C70039" },

"off-cpu-zfs-read": {"value": 4, "color": "#FFC300" },

"off-cpu-zfs-write": {"value": 5, "color": "#338AFF" },

"off-cpu-zil-commit": {"value": 6, "color": "#66FFCC" },

"off-cpu-tx-delay": {"value": 7, "color": "#CCFF00" },

"off-cpu-dead": {"value": 8, "color": "#E0E0E0" },

"wal-init": {"value": 9, "color": "#dd1871" },

"wal-init-tx-delay": {"value": 10, "color": "#fd4bc9" }

}

}](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/statemapkubecon-181210194032/85/Visualizing-Systems-with-Statemaps-19-320.jpg)