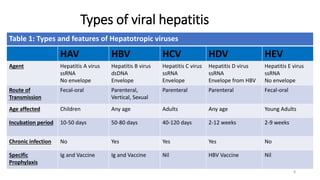

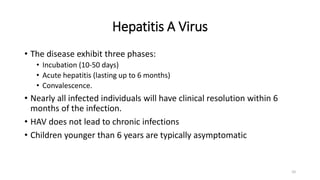

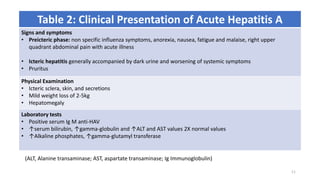

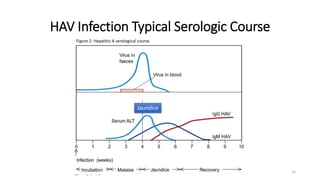

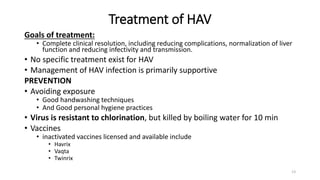

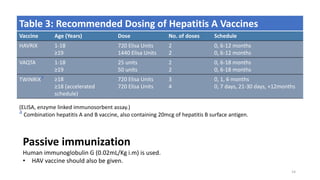

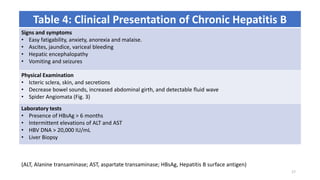

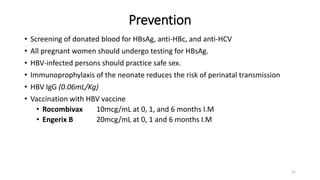

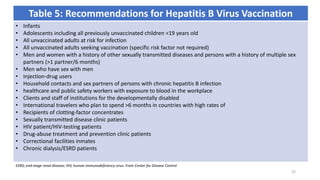

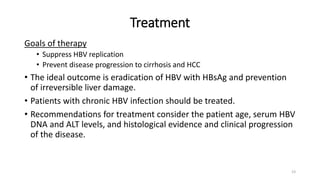

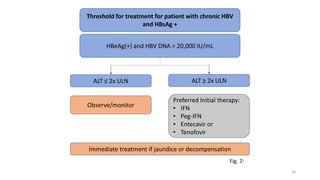

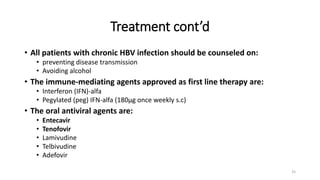

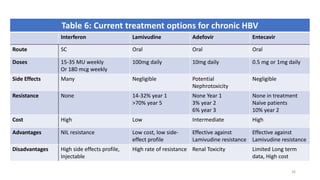

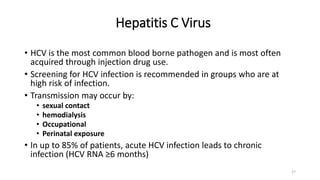

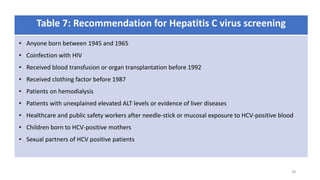

This document provides an overview of viral hepatitis, focusing on hepatitis A, B, C, D, and E viruses. It discusses the routes of transmission, clinical presentations, diagnostic markers, and treatment approaches for each type of viral hepatitis. The aims are to identify and discuss the various types of viral hepatitis, their clinical presentations, preventive measures, and available treatment regimens. Key points covered include the types of hepatotropic viruses that cause hepatitis, acute versus chronic infection, vaccination recommendations, and goals of antiviral therapy for chronic hepatitis B.

![References

• Koda-Kimble and Young’s: Viral Hepatitis, Applied Therapeutics the Clinical Use of Drugs 10th ED;

p1832

• Feather A, Randall D, Waterhouse M: Liver Disease, Kumar and Clark’s Clinical Medicine 10th ED

2021 p1284

• Wells BG, Schwinghammer TL, DiPiro JT, DiPiro CV; Viral Hepatitis: Pharmacotherapy Handbook

10th ED 2015 p341

• Kellerman RD, Rakel D.P. Hepatitis A, B, D and E, Conn’s Current Therapy 2019 p973

• Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 2017—Outbreaks of hepatitis A in multiple

states among people who are homeless and people who use drugs.

https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/outbreaks/2017March-hepatitisA.htm

• Lemon SM et al. Type A viral hepatitis: a summary and update on the molecular virology,

epidemiology, pathogenesis and prevention. J Hepatol. 2018 Jan;68(1):167–84. [PMID: 28887164]

• Linder KA et al. JAMA patient page. Hepatitis A. JAMA. 2017 Dec 19;318(23):2393. [PMID:

29094153]

46](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/viralhepatitisoverview-210401173903/85/Viral-hepatitis-overview-46-320.jpg)