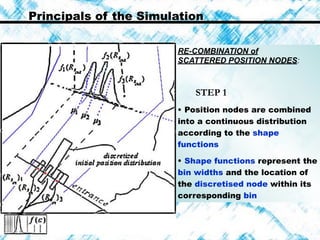

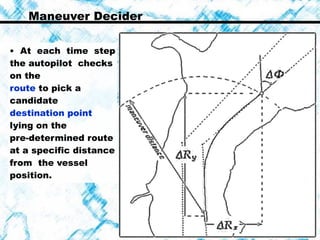

This document summarizes a stochastic modeling study of transit vessel traffic through the Strait of Istanbul. The objectives were to quantify casualty risk variation based on vessel size and different regions of the Strait. A mathematical simulation was developed using stochastic parameters like vessel length and pilot error. Position distributions were evaluated along checklines. Collision and grounding risks were highest for certain regions and supported statistical data. Further improvements could incorporate more detailed hydrodynamics and bathymetry.