The document is a foreword for a study guide called "The USMLE Step 1 BIBLE" for the United States Medical Licensing Exam Step 1. It was written to help students understand medicine and score as high as possible on the exam. It covers high-yield topics in depth to adequately prepare students. The best way to use the guide is combined with a quality question bank.

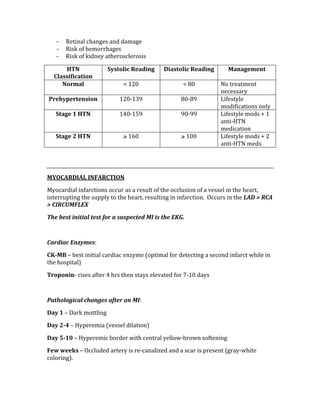

![Negative Predictive Value = d/d + c

The NPV is used to determine the probability of not having a condition when the test

result is negative.

Odds Ratio = (a/b)/ (c/d)

The OR determines the incidence of disease in people in the exposed groups divided

by those in an unexposed group.

OR > 1 = States that the factor being studied is a risk factor for the outcome

OR<1 = States that the factor being studied is a protective factor in respect to the

outcome

OR = 1, States that no significant difference in outcome in either exposed or

unexposed group

Relative Risk = [a/(a+b) / d/(c+d)]

Relative risk compares the disease risk in people exposed to a certain factor with

disease risk in people who have not been exposed

Attributable Risk = [a/(a+b) – d/(c+d)]

The attributable risk is the number of cases that can be attributed to one risk factor

INCIDENCE vs. PREVALENCE

Incidence is the number of new cases of a disease over a unit time, whereas

prevalence is the total number of cases of a disease (both new and old) at a certain

point in time. Any disease treated with the sole purpose of prolonging life (ie

terminal cancers), the incidence stays the same but prevalence will increase.

Shortterm diseases: Incidence > Prevalence

Longterm diseases: Prevalence > Incidence

VALIDITY vs. RELIABILITY

Validity is simply a test’s ability to measure what it claims to measure, whereas the

reliability of a test determines its ability to consistent results on repeated attempts.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/usmlestep1biblewithnotes-150512235651-lva1-app6891/85/Usmle-Step-1-Bible-201-320.jpg)

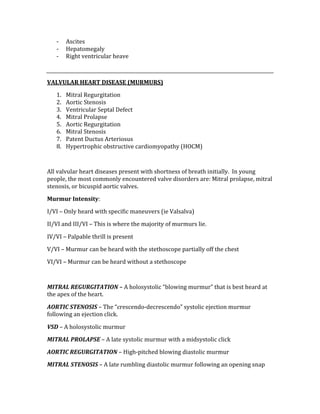

![CONFIDENCE INTERVAL AND pVALUE

These values strengthen the results of a study. For statistical significance, the CI

mustn’t contain the null value (RR = 1), and the closer the two numbers are

together, the more confident you can be that the results are statistically significant.

As far as the significance of the p‐value goes, a statistically significant result has a p‐

value of <0.05 (this means there is <5% chance that the results obtained were due

to chance alone).

CORRELATION COEFFICIENT

Two numbers that are between ‐1 and +1, it measures to what degree the variables

are related.

‐ A number of zero (0) means there is no correlation between variables.

‐ A number of +1 means there is a perfect correlation (both variables increase

or decrease proportionally)

‐ A number of ‐1 means there is a perfect negative correlation (variables move

in opposite directions proportionally)

ATTRIBUTABLE RISK PERCENT (ARP)

The ARP measures the impact of the particular risk factor being studied on a

particular population. It represents excess risk that can be explained by exposure to

a particular risk factor.

Calculate the ARP: ARP = [(RR ‐1)/RR]

STATISTICAL HYPOTHESES

The statistical hypotheses are used to determine whether or not there is an

association between risk factors and disease in a population. They are the ‘null

hypothesis’ and the ‘alternative’ hypothesis.

Null Hypothesis (Ho) – This hypothesis is the ‘hypothesis of no difference’, meaning

there is not an association between the disease and the risk factor.

Alternative Hypothesis (H1) – This hypothesis is the ‘hypothesis of some

difference’, meaning there is an association between the disease and the risk factor.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/usmlestep1biblewithnotes-150512235651-lva1-app6891/85/Usmle-Step-1-Bible-205-320.jpg)

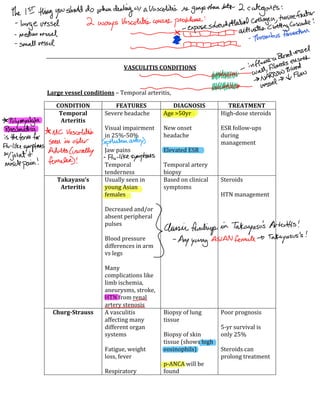

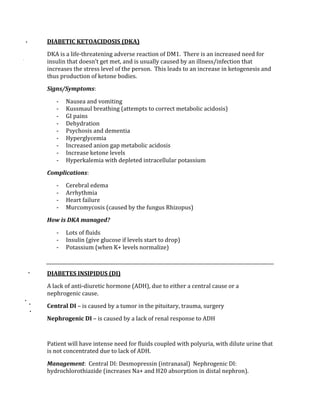

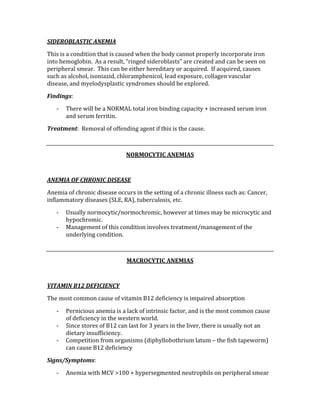

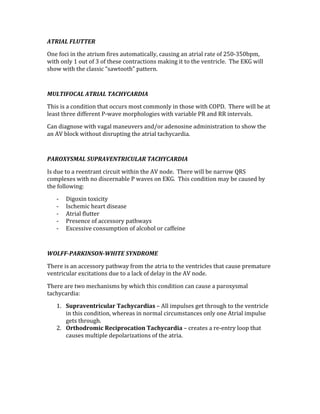

![ACID/BASE PHYSIOLOGY

Problem pH PCO2 [HCO3] Compensation Causes

Metabolic

Acidosis

⇓ ⇓ ⇓⇓ Patient will

hyperventilate

to blow off CO2

DKA, ASA

overdose,

lactic

acidosis

Respiratory

Acidosis

⇓ ⇑⇑ ⇑ Bicarb

absorption in

kidney

Obstruction

of airway

Respiratory

Alkalosis

⇑ ⇑⇑ ⇓ Kidney

secretes bicarb

Hypervent,

high alt.

Metabolic

Acidosis

⇑ ⇓ ⇑⇑ Pt will

hypoventilate

vomiting](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/usmlestep1biblewithnotes-150512235651-lva1-app6891/85/Usmle-Step-1-Bible-424-320.jpg)