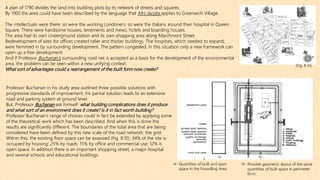

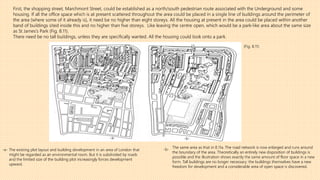

The document discusses urban planning and city grids. It begins by questioning traditional planning assumptions and doctrines. It then provides examples of cities with artificial grids imposed from the beginning, like Savannah and Manhattan, and how these grids still allowed for organic growth. While grids can result in monotony, they can also provide structure that enables growth. The key is finding the right balance between plot and building size and the street network. With the right framework, the same level of development can be achieved in a more open, organic layout compared to a clustered one.