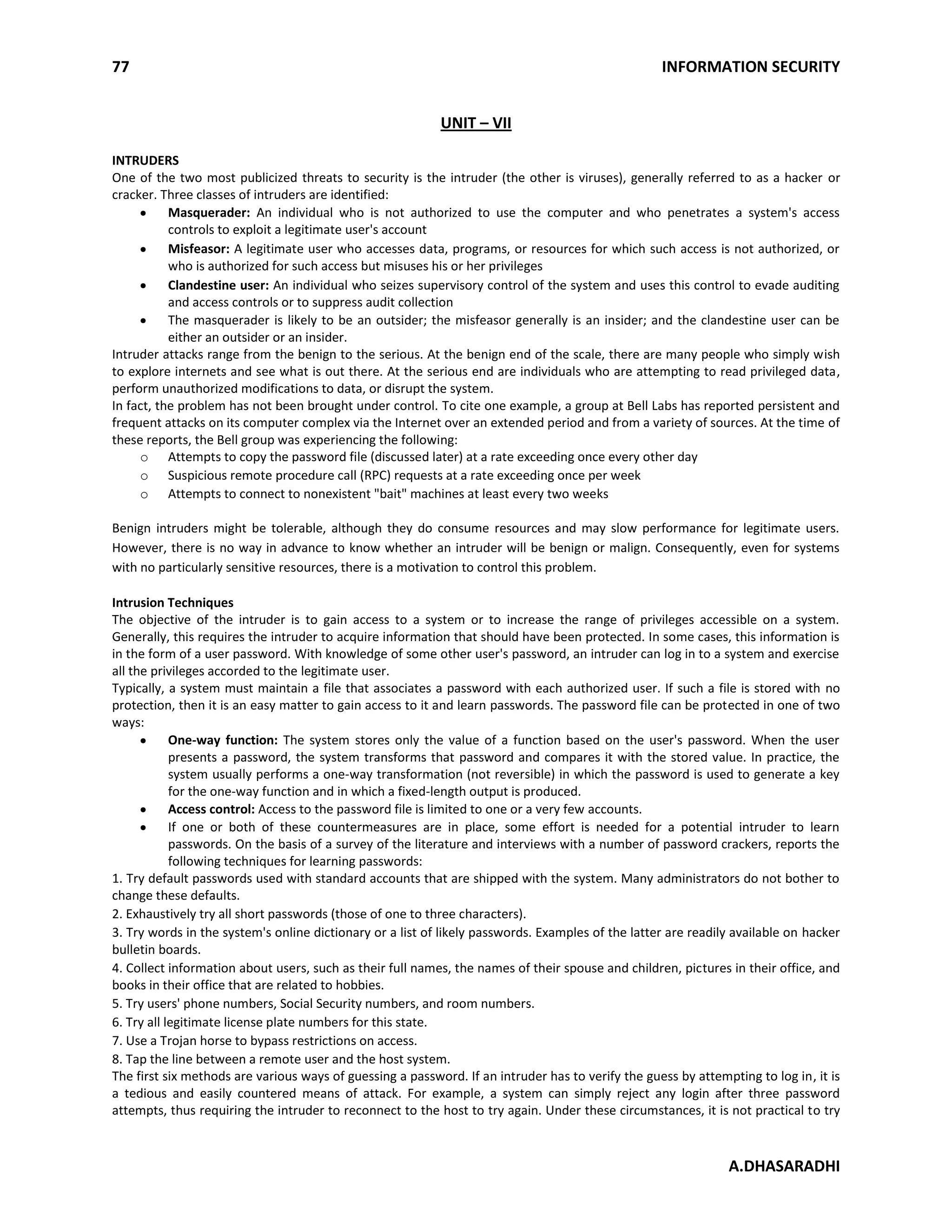

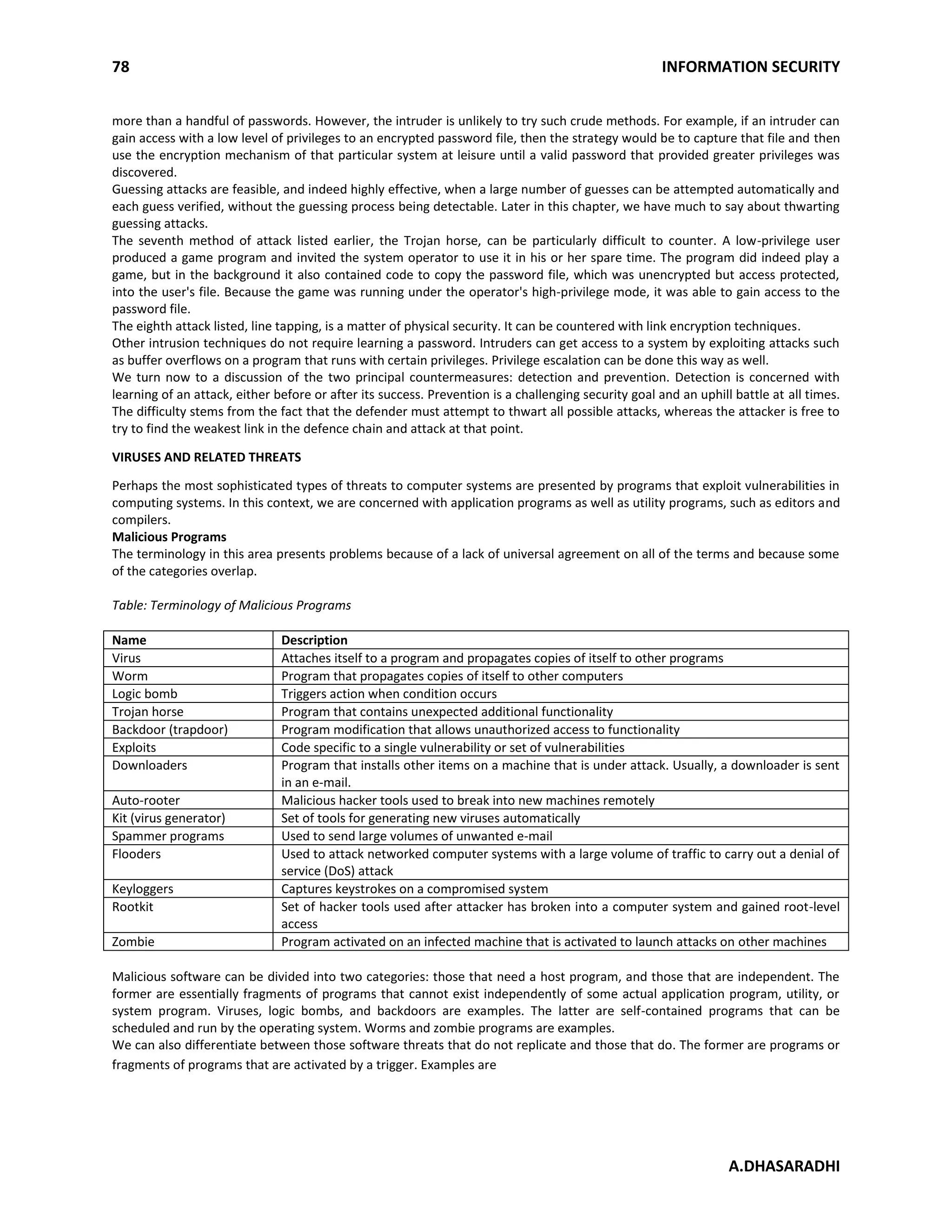

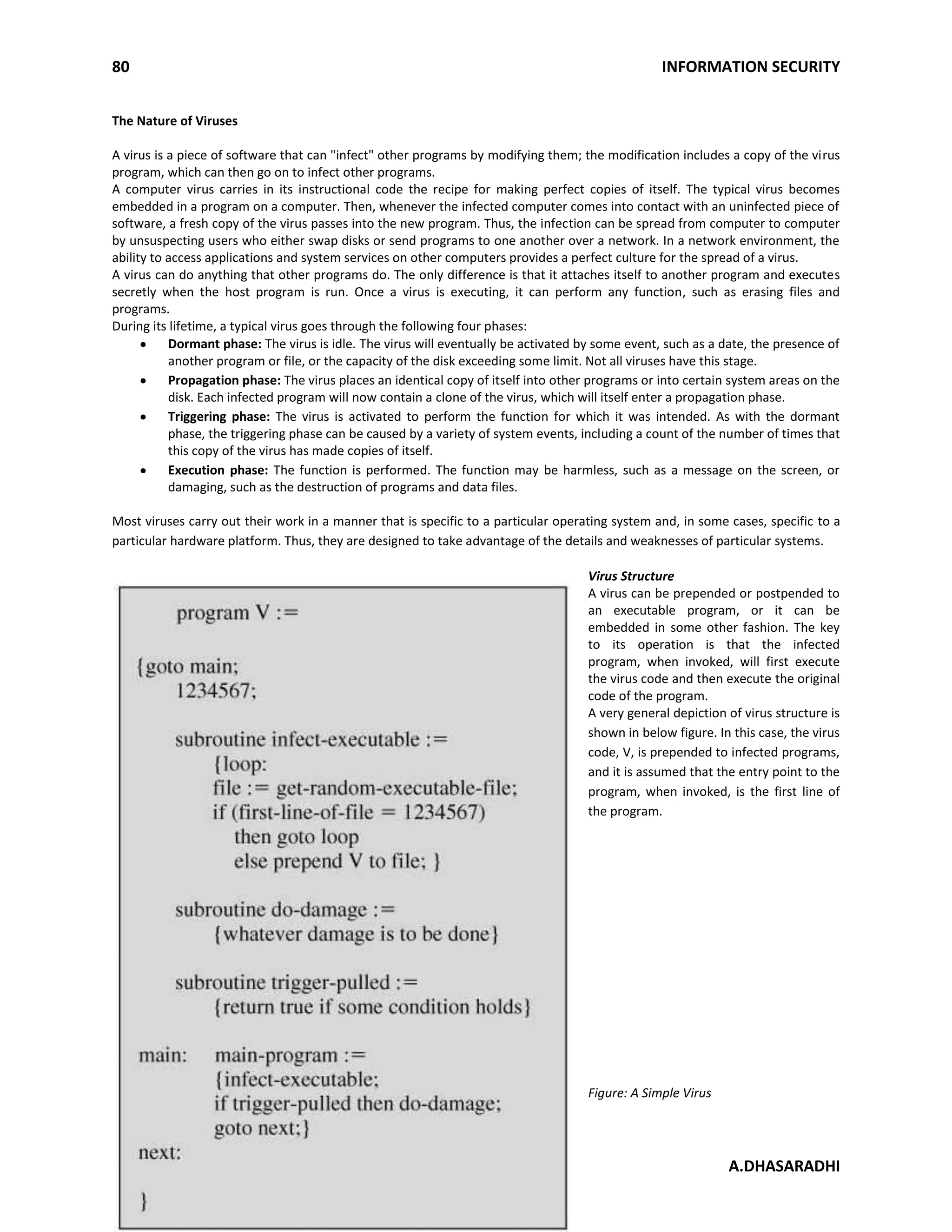

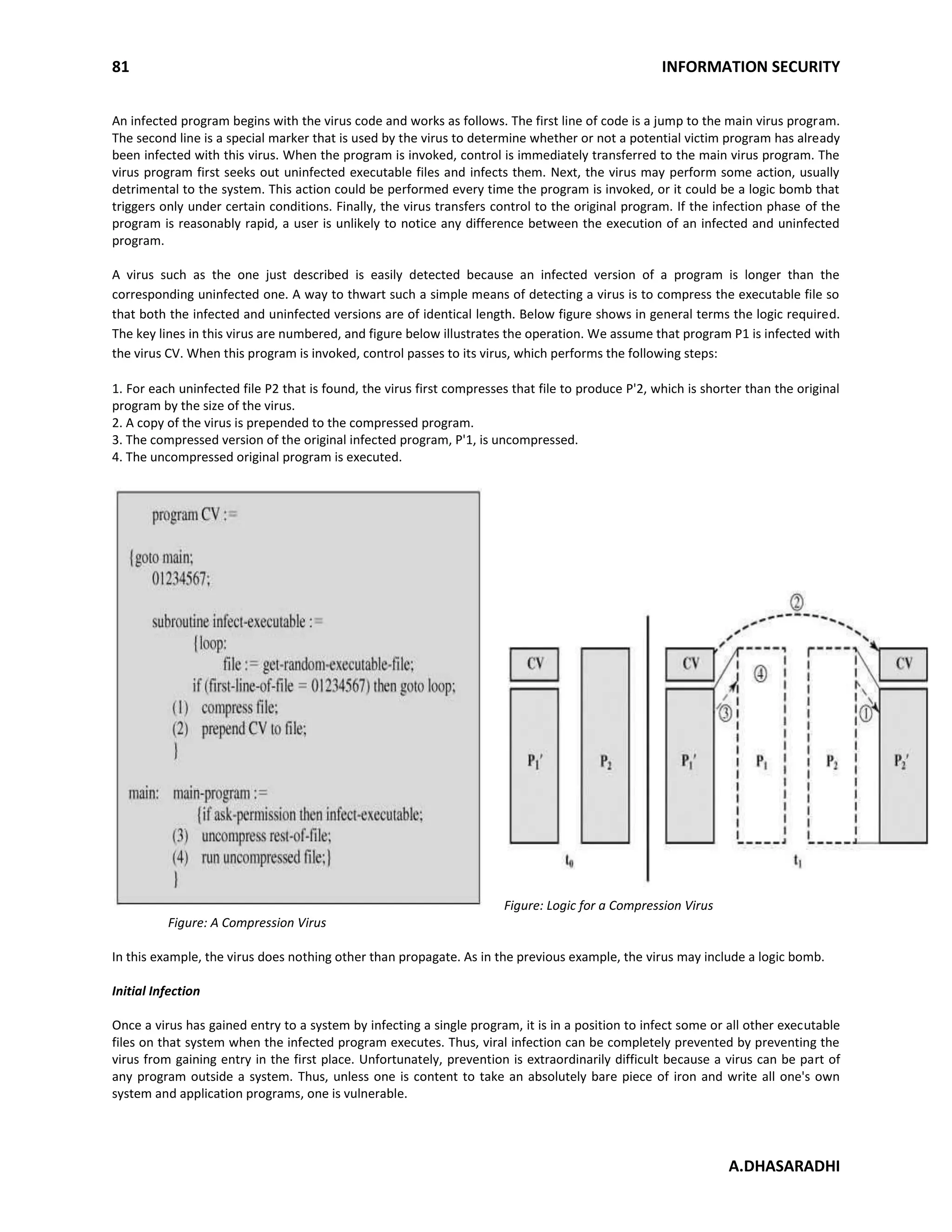

Intruders threaten computer security and are classified as masqueraders, misfeasors, or clandestine users. Intruder attacks range from benign to serious, seeking unauthorized access, data modification, or system disruption. A persistent problem is frequent attacks on computer systems via the internet from various sources, including attempts to copy password files, suspicious remote procedure calls, and attempts to connect to nonexistent machines. Intruders aim to gain access or privileges by techniques like guessing default passwords, short passwords in dictionaries, or personal information, or using Trojan horses or line tapping to bypass access controls. Malicious programs also threaten security and are classified based on behaviors like attaching to programs to propagate (viruses), propagating