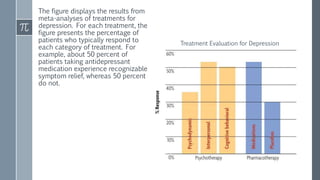

1. Researchers evaluate the effectiveness of therapies through methods like meta-analyses of existing studies to identify the most effective treatments for issues like depression. Common factors like the therapeutic relationship contribute to positive outcomes.

2. While therapies like CBT are supported as effective, researchers still do not fully understand why they work. Prevention strategies aim to reduce mental illness at the primary, secondary, and tertiary levels through skills training, early identification and treatment, and relapse prevention.

3. Evaluating therapeutic effectiveness and identifying common success factors helps improve treatments, while prevention research works to reduce mental illness occurrence and severity.