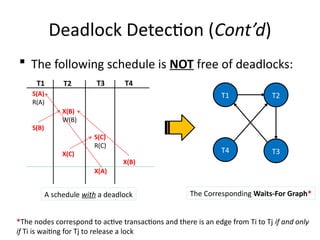

The document discusses transaction management in database systems, focusing on concurrency issues, locking protocols, and recovery methods. It explains the two-phase locking (2PL) protocol and its stricter variant, strict 2PL, which helps resolve anomalies such as read-write (RW), write-write (WW), and write-read (WR) conflicts. Additionally, it covers the importance of ensuring recoverable schedules to prevent cascading aborts, emphasizing the need for controlled locking mechanisms.