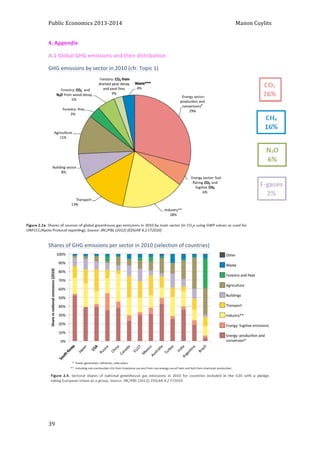

This document describes the use of modeling to analyze options for reducing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and their economic impacts. It discusses an accounting model called OPE2RA that was used to study scenarios for reducing Belgium's GHG emissions by 80-95% by 2050 compared to 1990 levels. The model establishes historical emissions by sector, builds baseline and mitigation scenarios by identifying reduction opportunities in sectors like transport, buildings, agriculture, industry and energy production, and analyzes scenario impacts on emissions, costs, energy use and other indicators.

![Public

Economics

2013-‐2014

Manon

Cuylits

Topic

5

:

Mitigation

options

“Reaching

80%

to

95%

GHG

emissions

reduction

[...]

is

possible.

Nevertheless,

reaching

this

target

is

very

challenging,

will

imply

large

reductions

in

all

sectors

and

a

thorough

understanding

of

the

various

interconnected

dimensions

is

key.”

Pestiaux

et

al.

(2013),

Scenarios

for

a

low

carbon

Belgium

by

2050,

Forthcoming

1.

Introduction

Objective

of

this

topic:

analyse

what

can

be

done

to

reduce

GHG

emissions

and

analyse

economic

impacts

of

these

actions

Models

are

used

to:

28

• Assess

the

emission

reduction

possibilities

at

the

level

of

a

sector/country/region/world

• Assess

the

impacts

of

emission

reductions

on

several

indicators

such

as

costs,

employment,

air

pollution,

etc...

This

requires

to

begin

with

a

clear

view

on:

• Possible

technological

levers

• Possible

behavioural

levers

• Their

combination

2.

Case-‐study

on

Belgium

:

OPEERA

accounting

model

2.1.

Overall

approach

• Establish

historical

GHG

emissions

per

sector

(starting

point,

e.g.

2010)

• Establish

a

mid-‐term

or

long-‐term

“business-‐as-‐usual”

scenario

(e.g.

up

to

2020

or

2050),

i.e.

under

no

additional

policies/measures/actions,

to

be

used

as

a

benchmark/reference

against

which

the

impact

of

targets/policies/

actions

(levers)

are

to

be

assessed;

• In

each

(sub)sector,

identify

emission

reduction

levers

and

possible

ambition

levels

for

each

lever:

o Possible

technologies

aimed

at

reducing

GHG

emissions,

with

due

attention

to

the

level

of

deployment

(existing,

in

demonstration

phase,

in

R&D

phase,

...)

o Activity

levels,

such

as

travel

demand

per

person

or

industrial

production

• Build

scenarios,

i.e.

coherent

set

of

assumptions

and

levers

leading

to

required

level

of

total

emission

reductions

in

2050

• Analyse

the

impacts

of

each

scenario

on

e.g.

energy

security,

final

energy

demand,

costs,

etc...

Source:

Pestiaux

et

al.

(2013)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/topic5-mitigationoptions-141127132453-conversion-gate02/75/Topic-5-mitigation-options-1-2048.jpg)