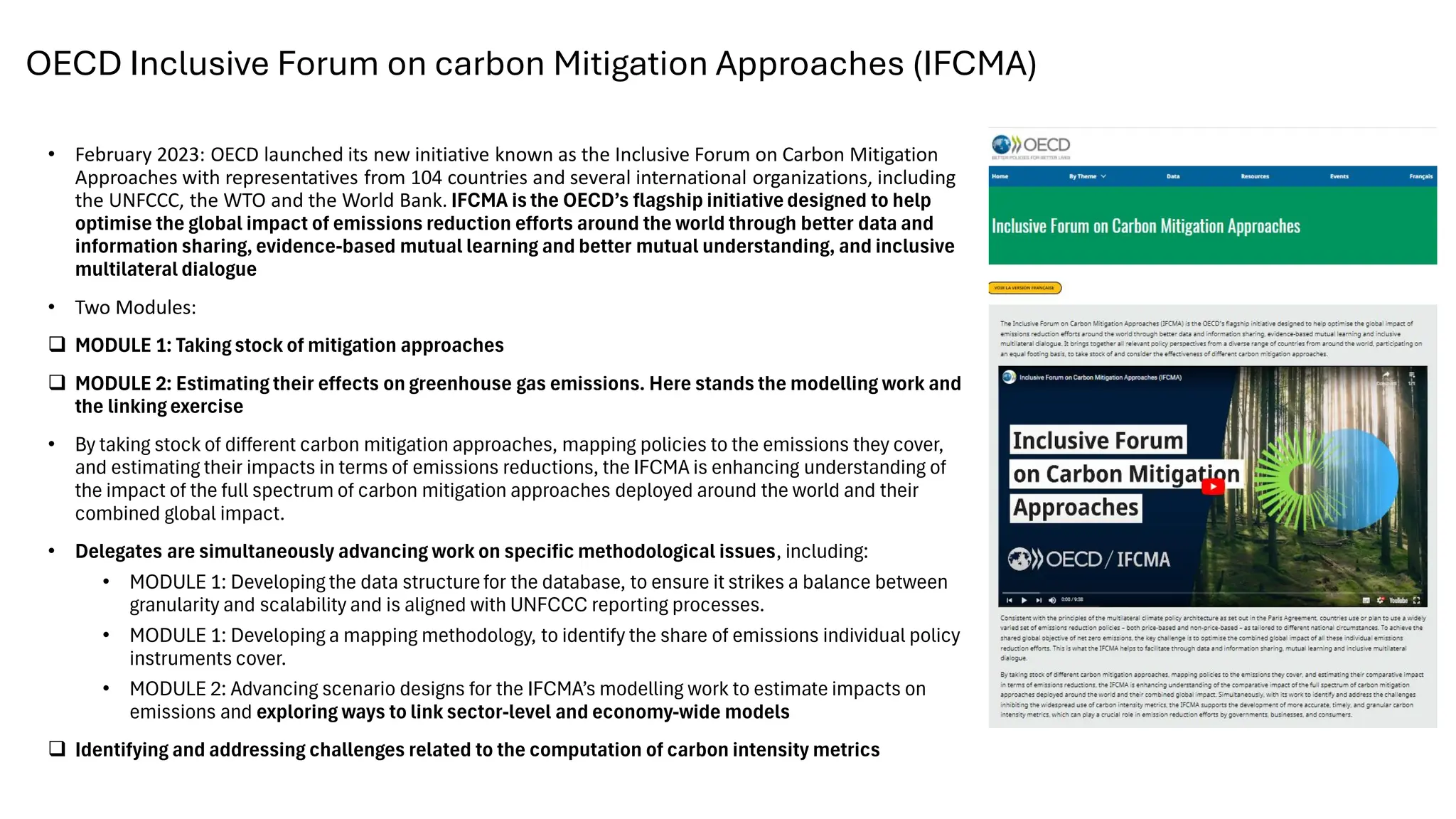

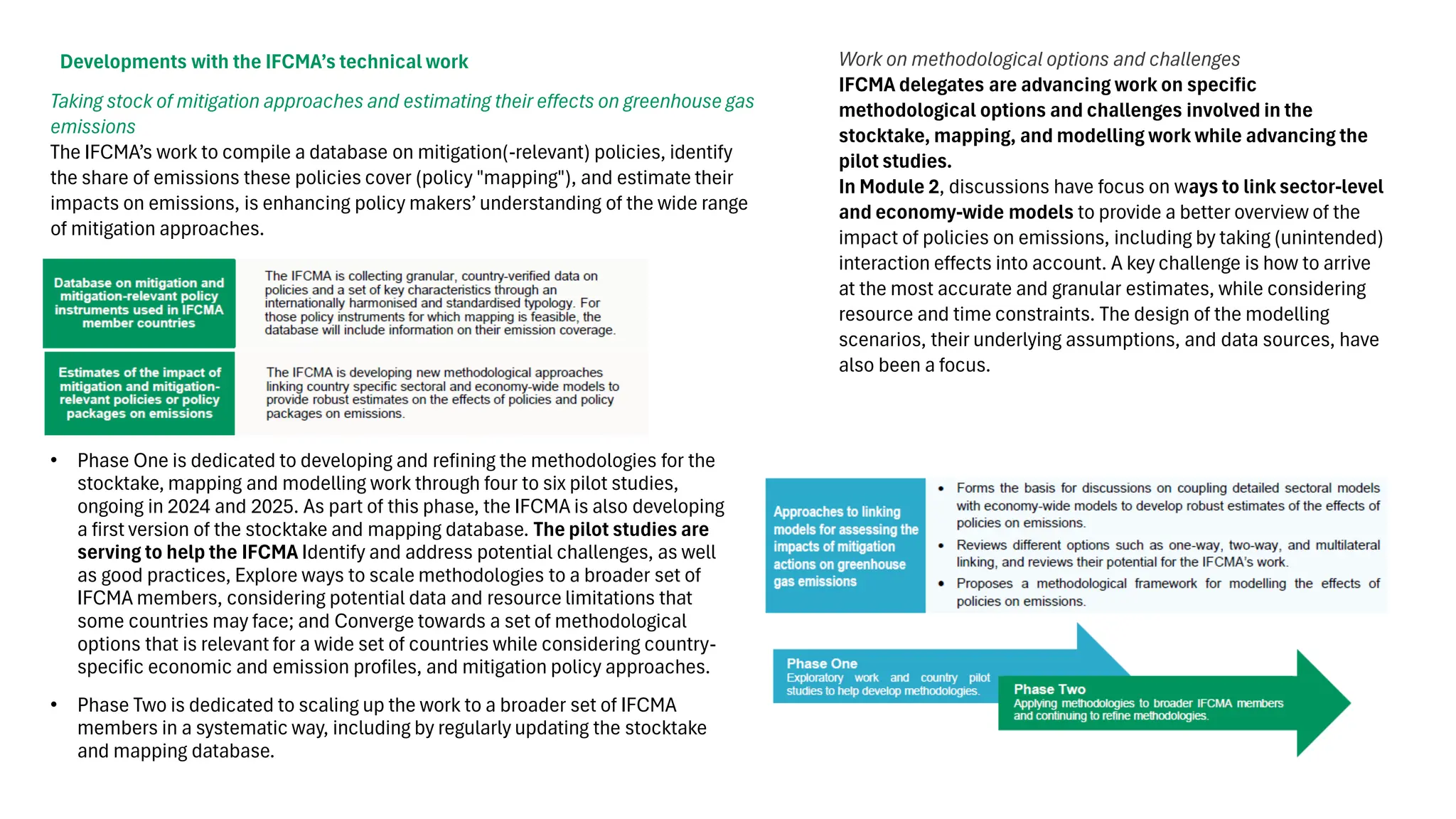

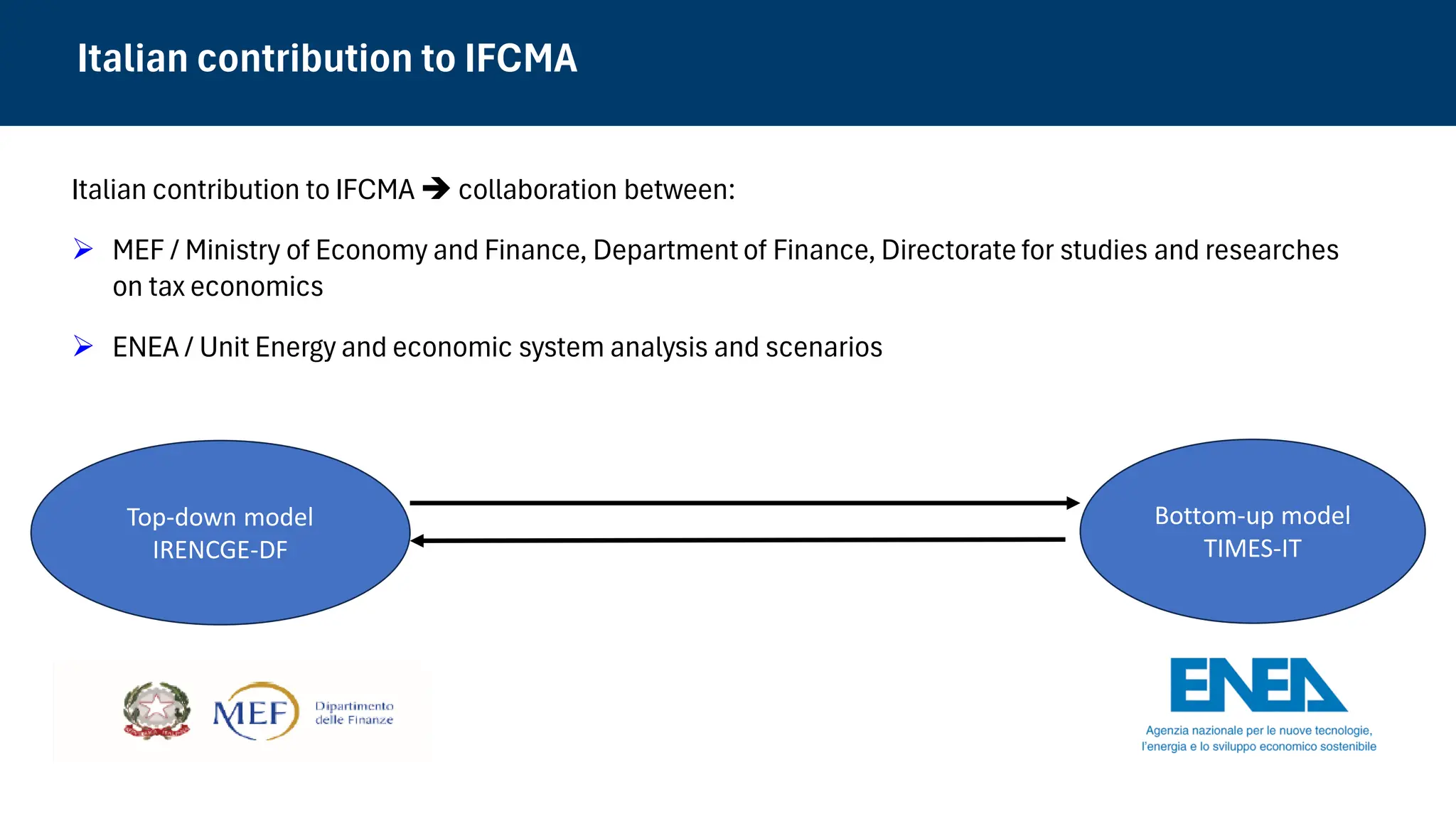

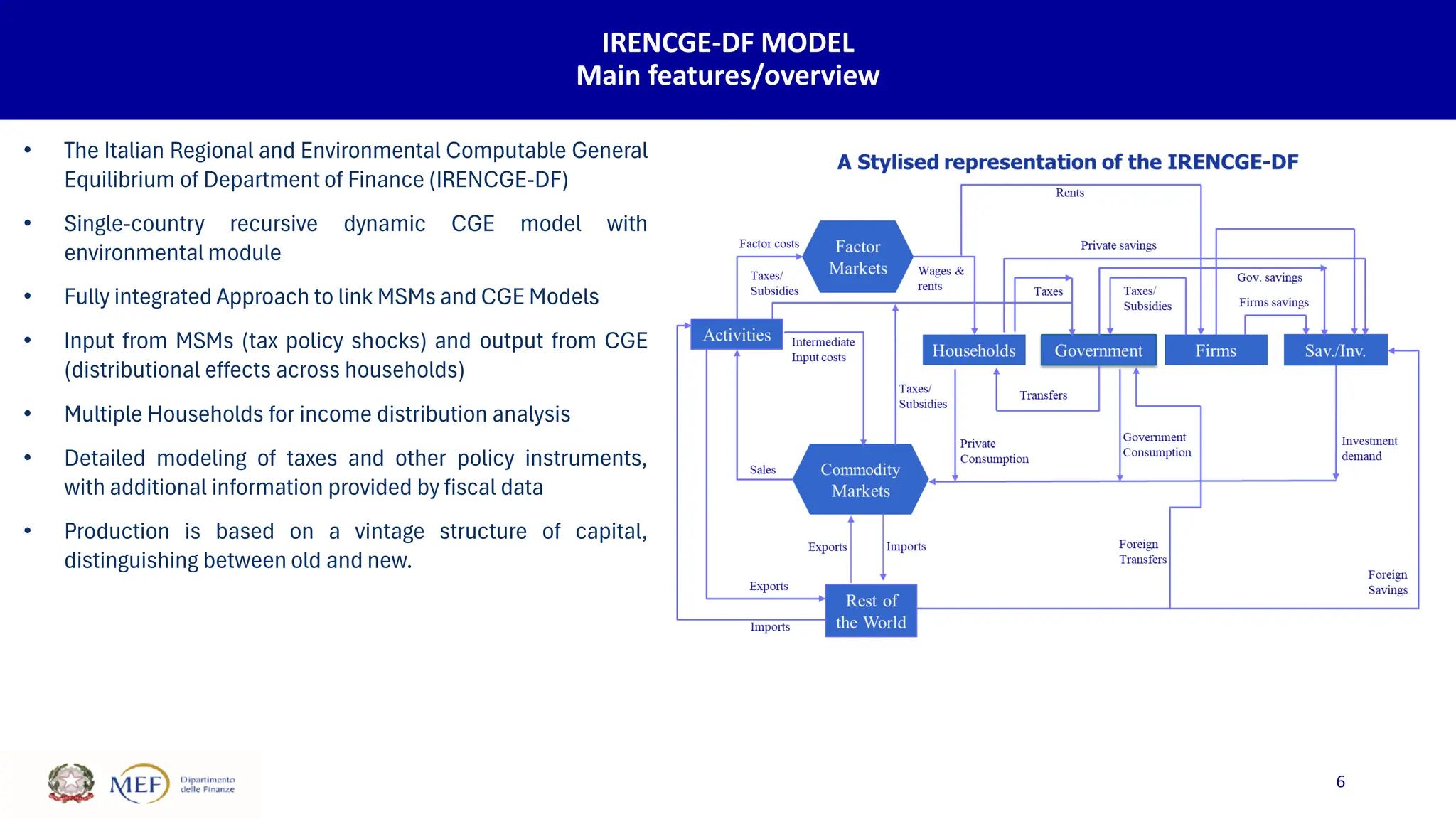

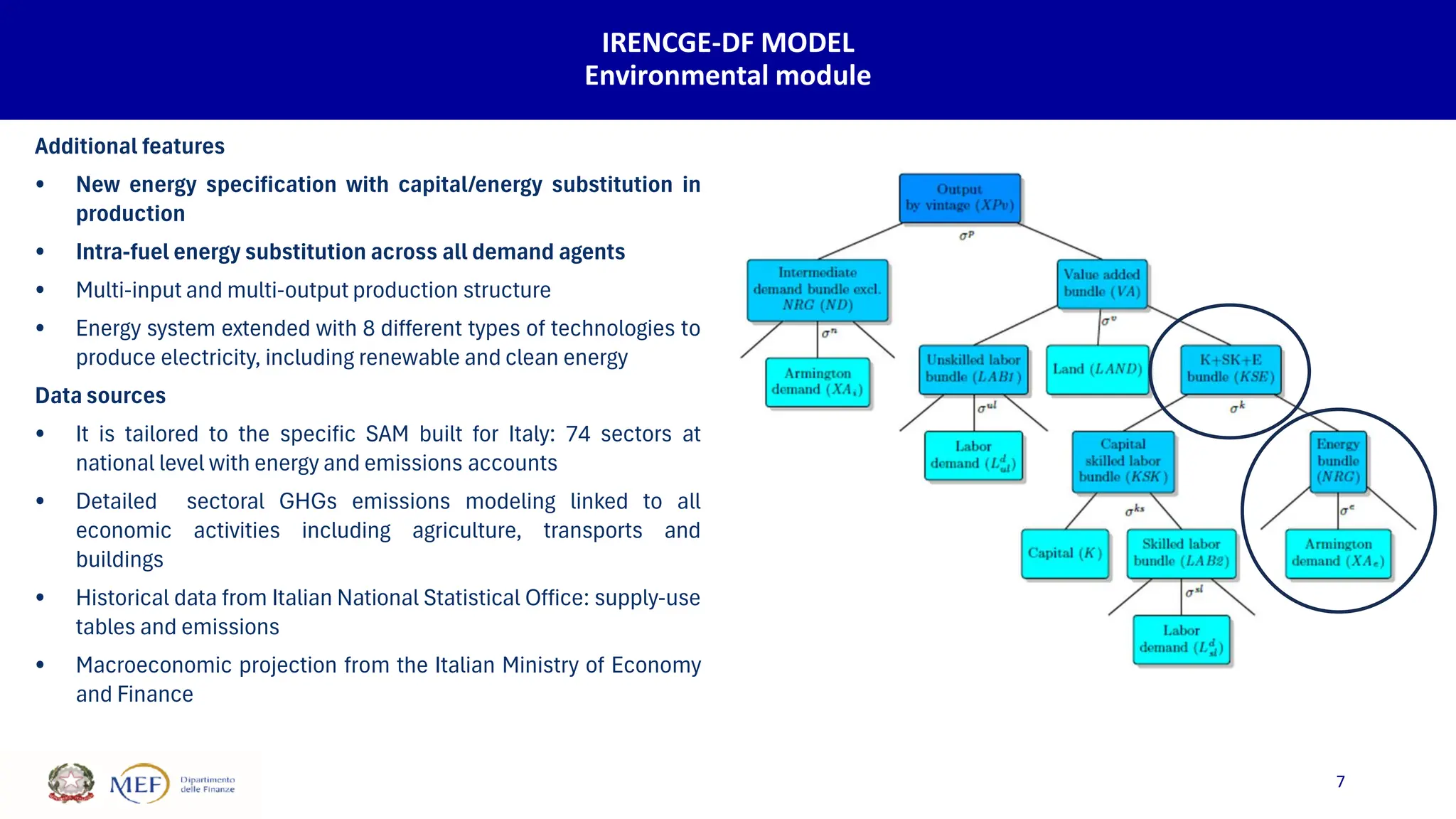

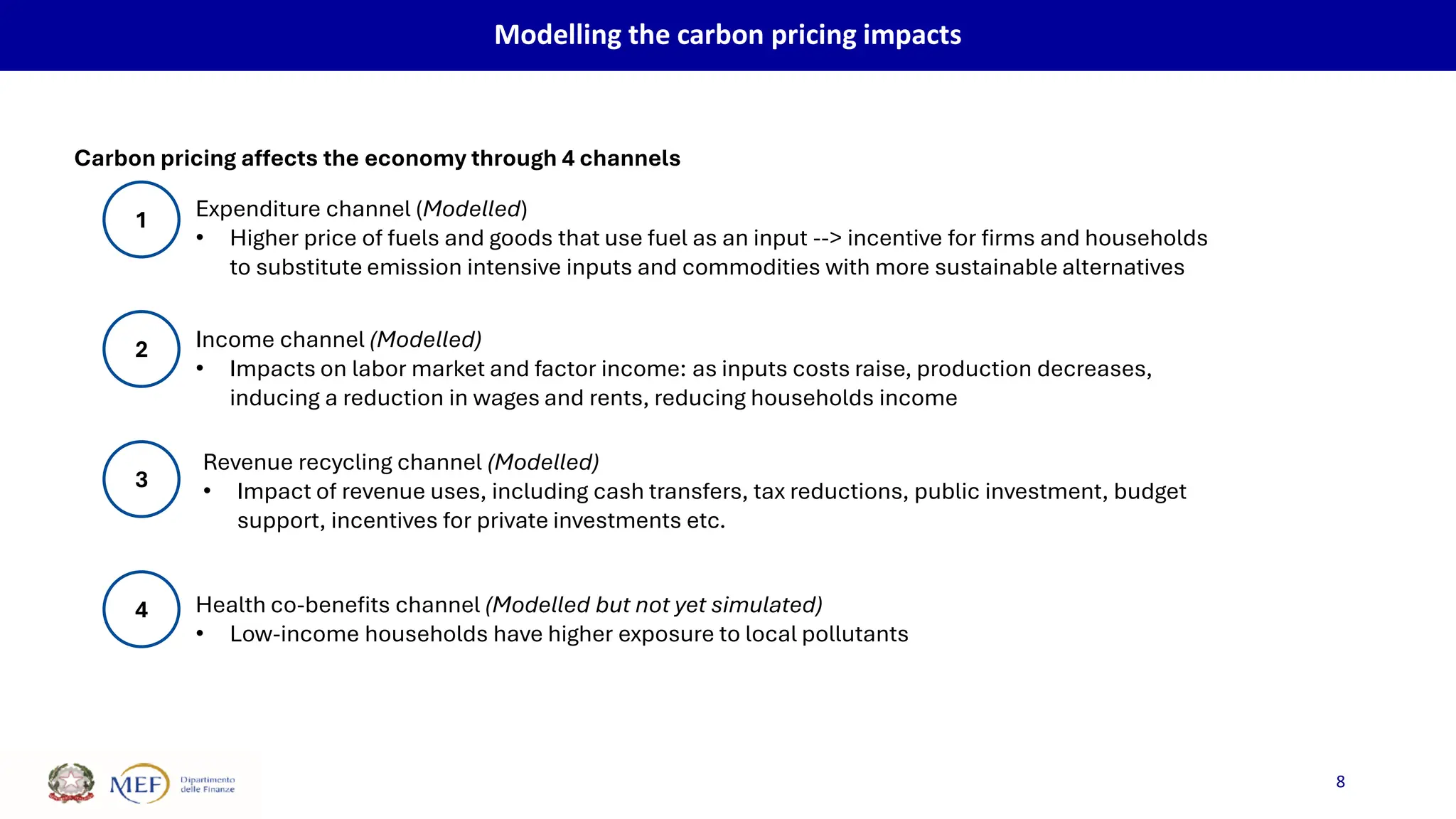

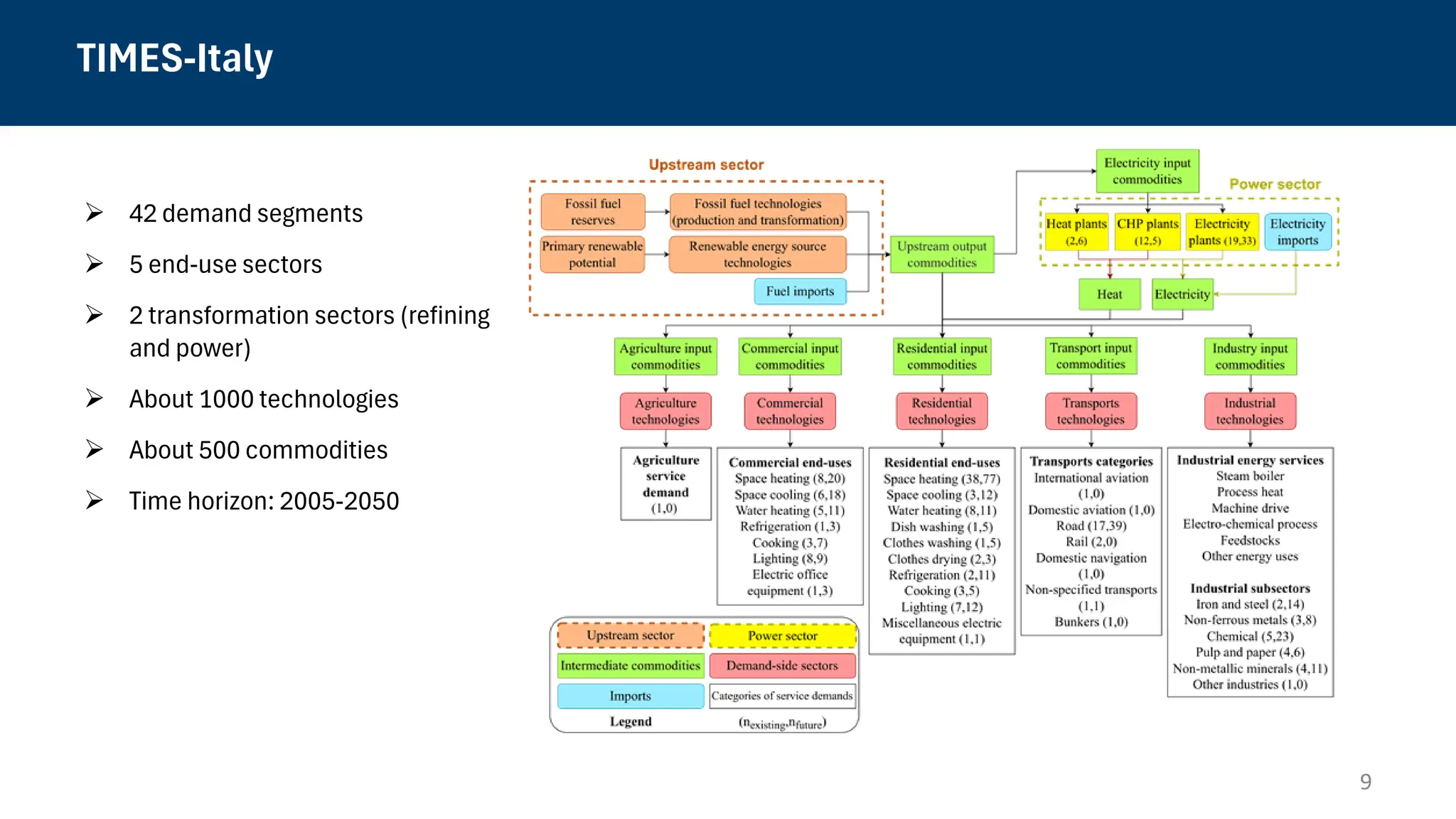

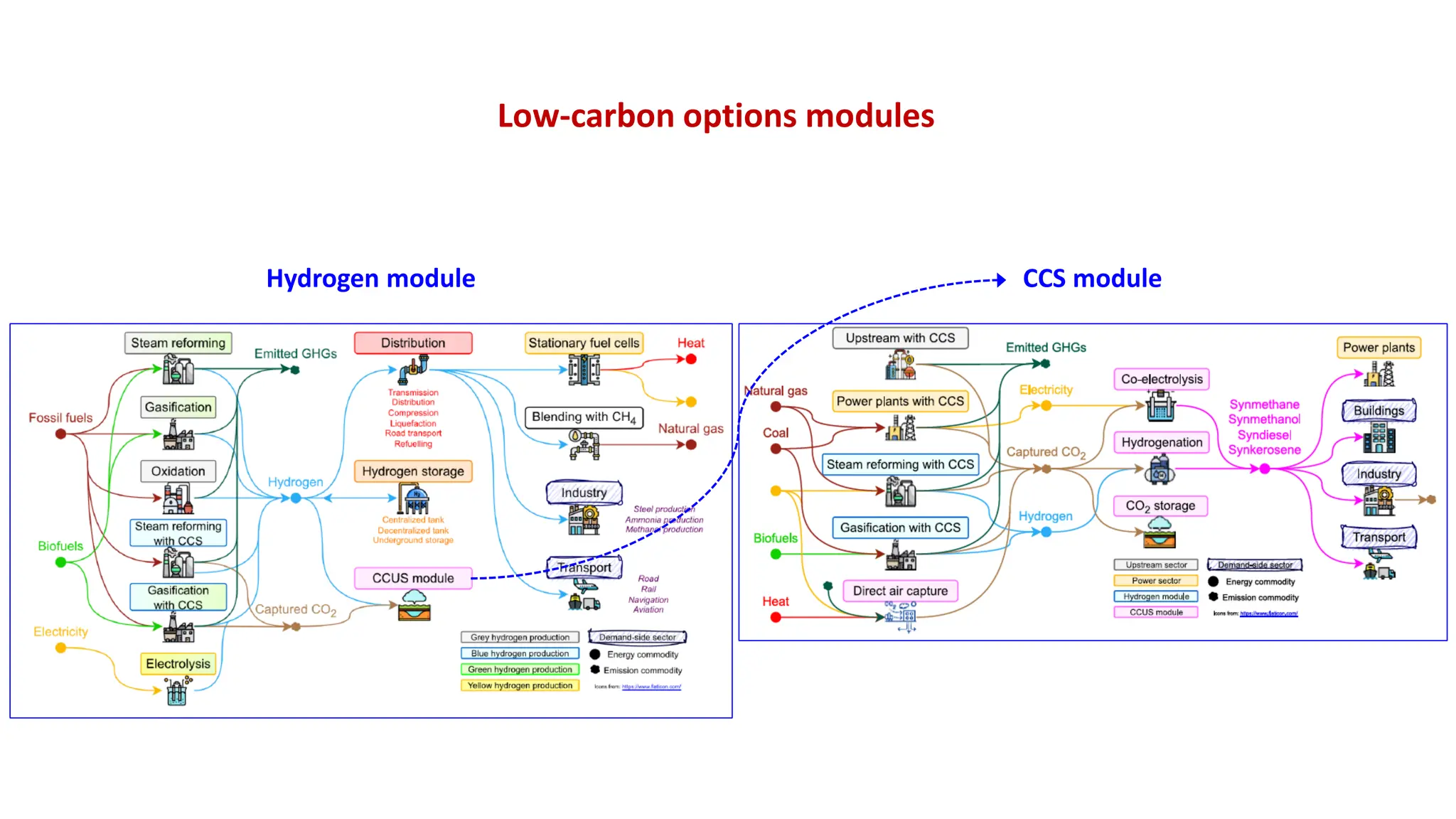

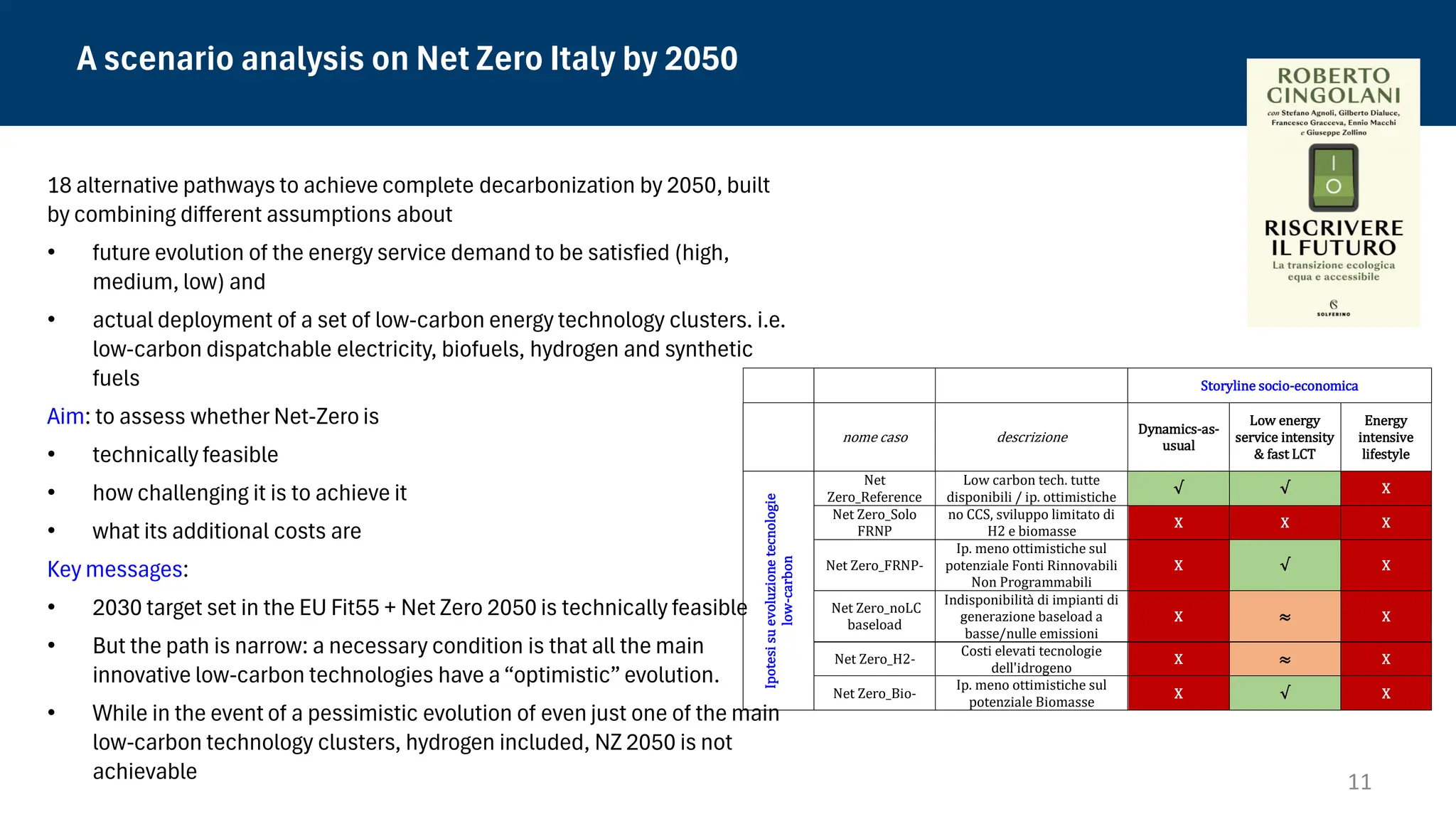

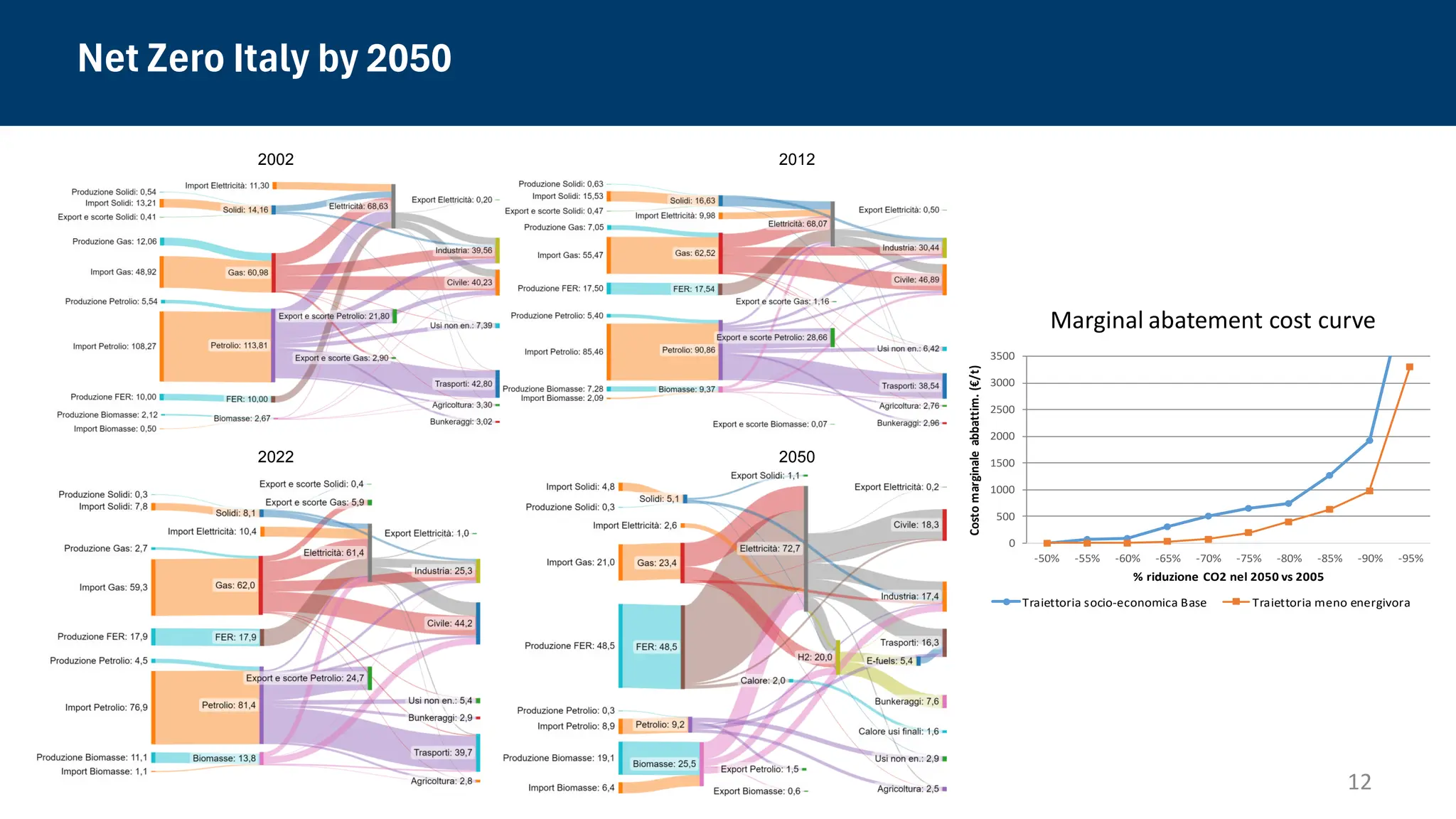

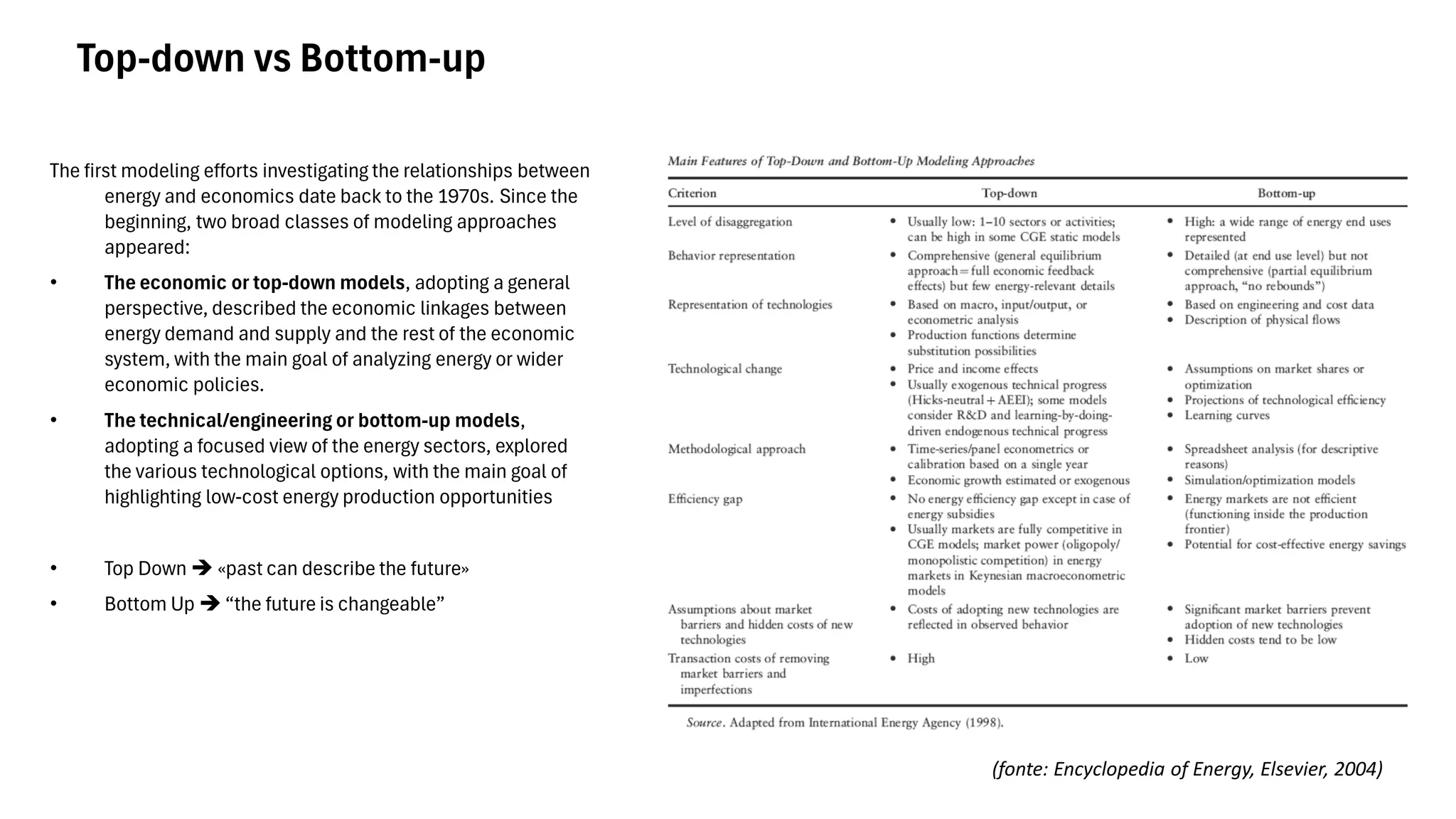

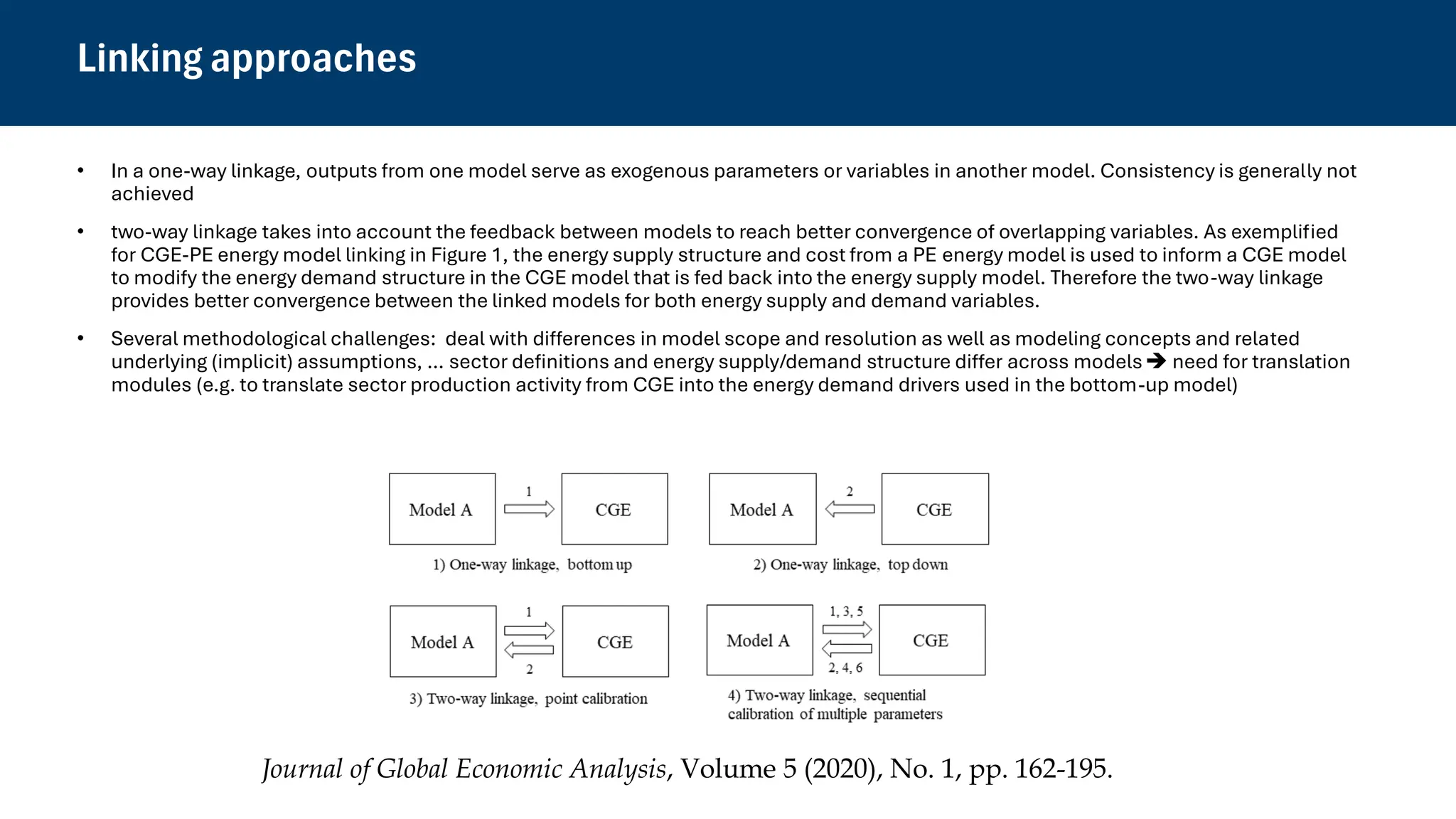

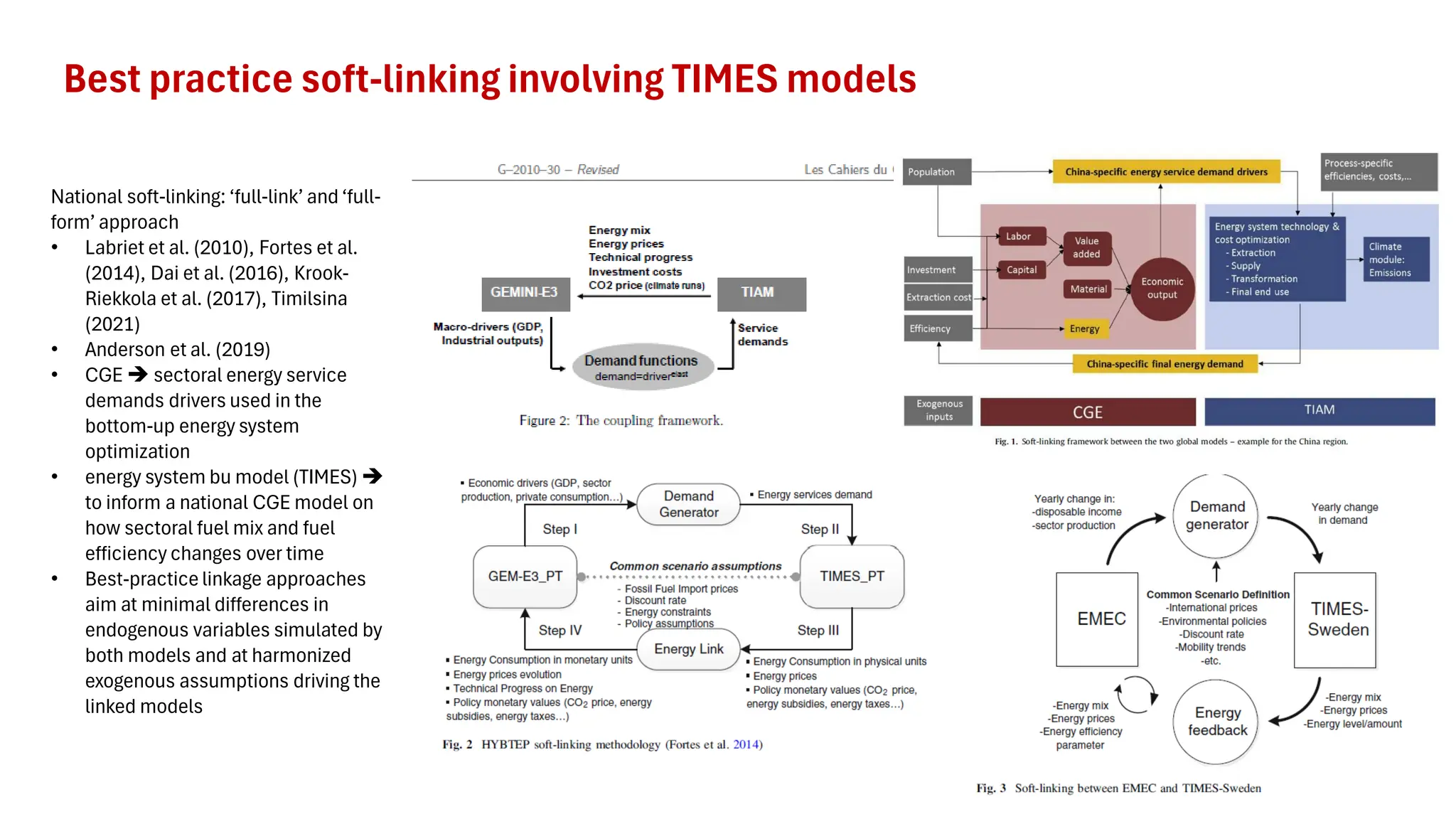

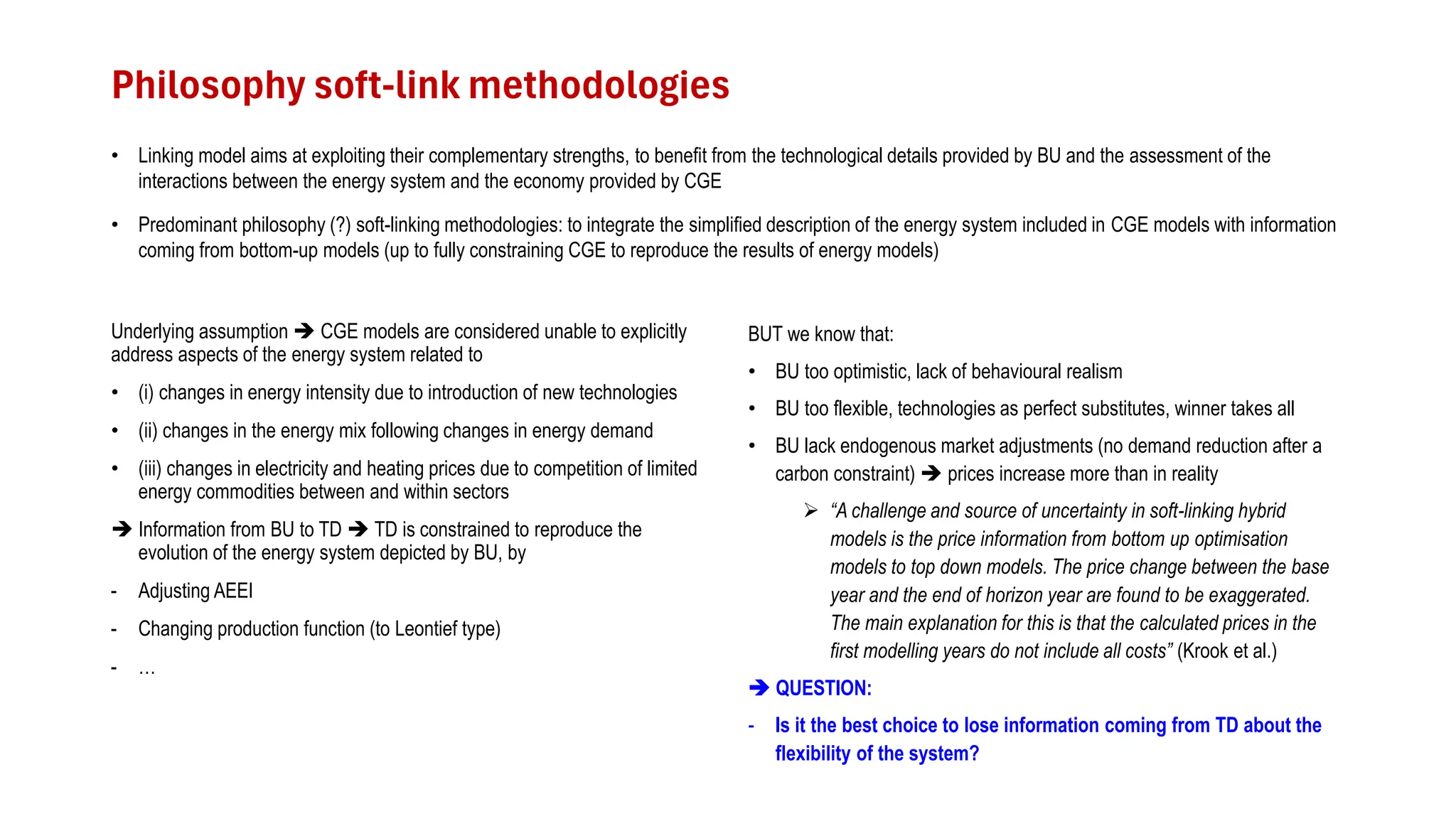

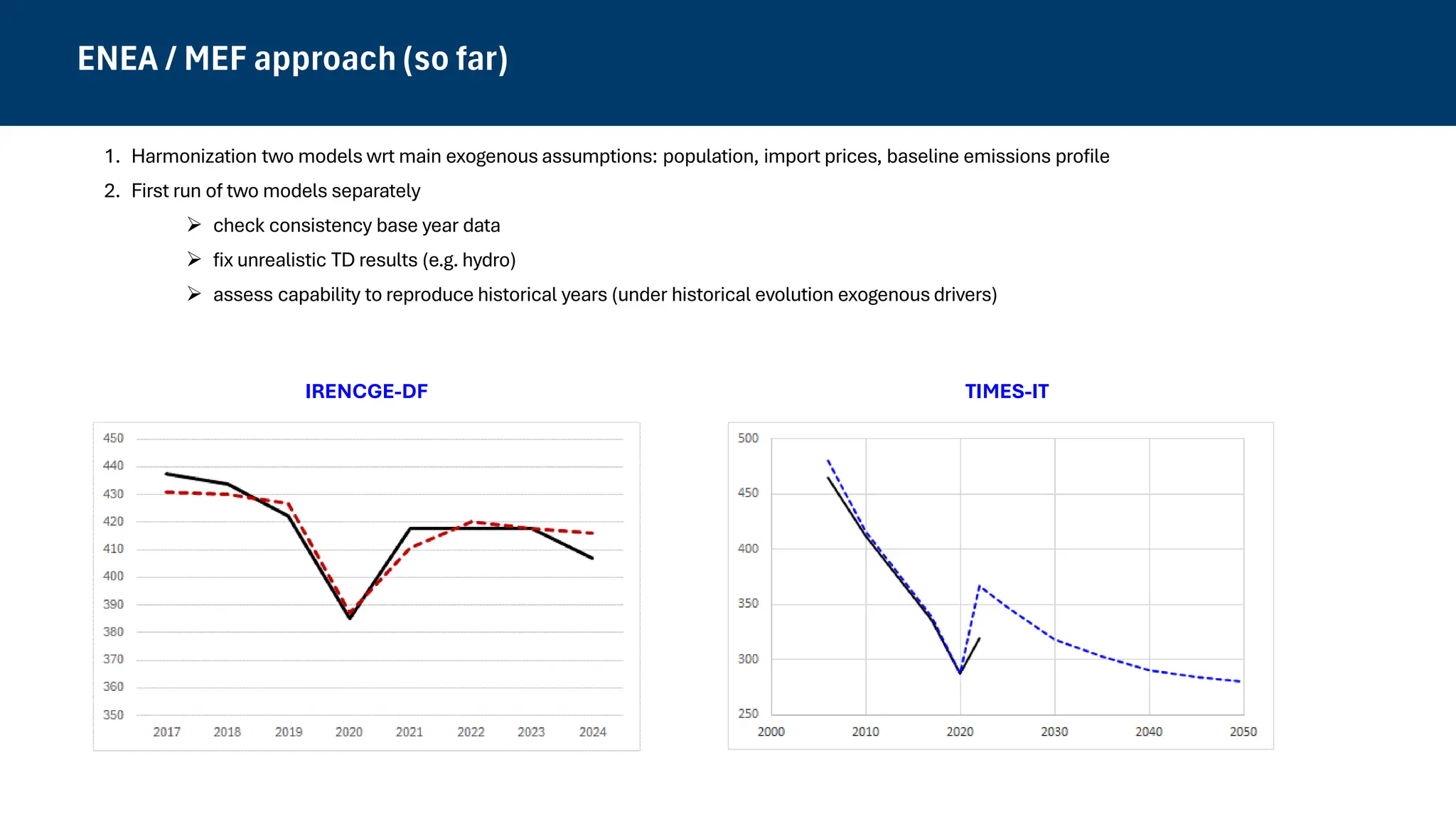

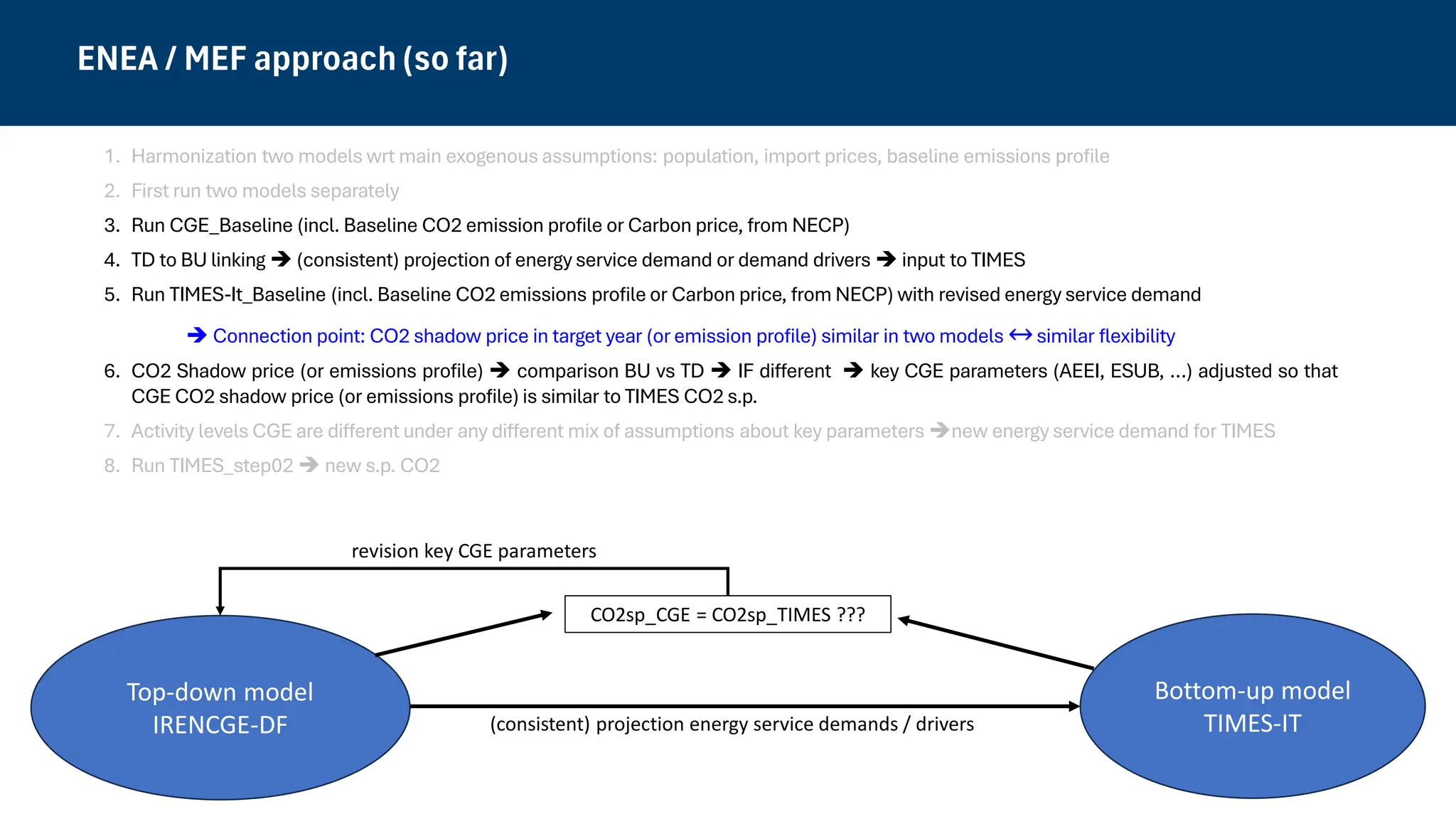

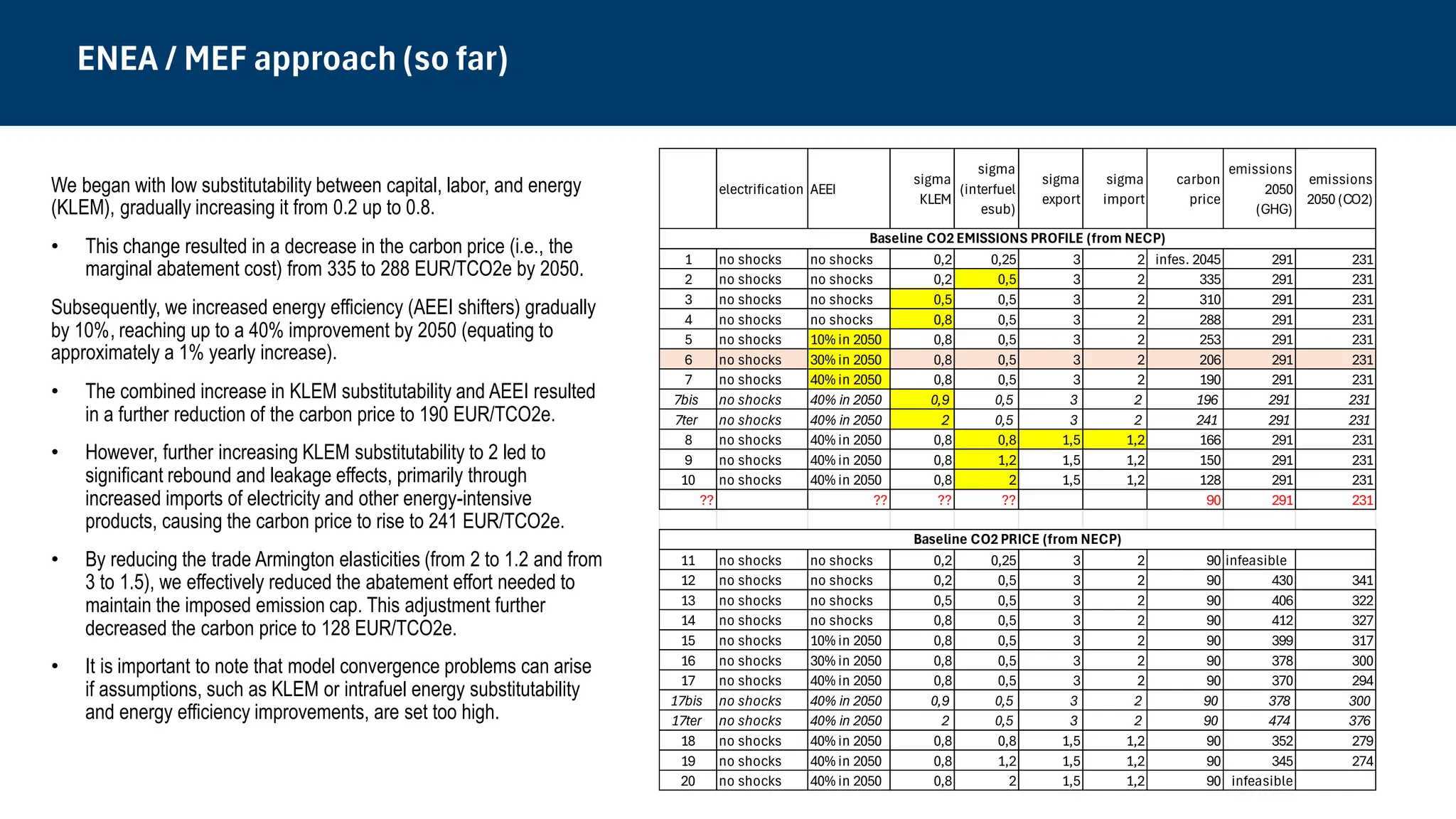

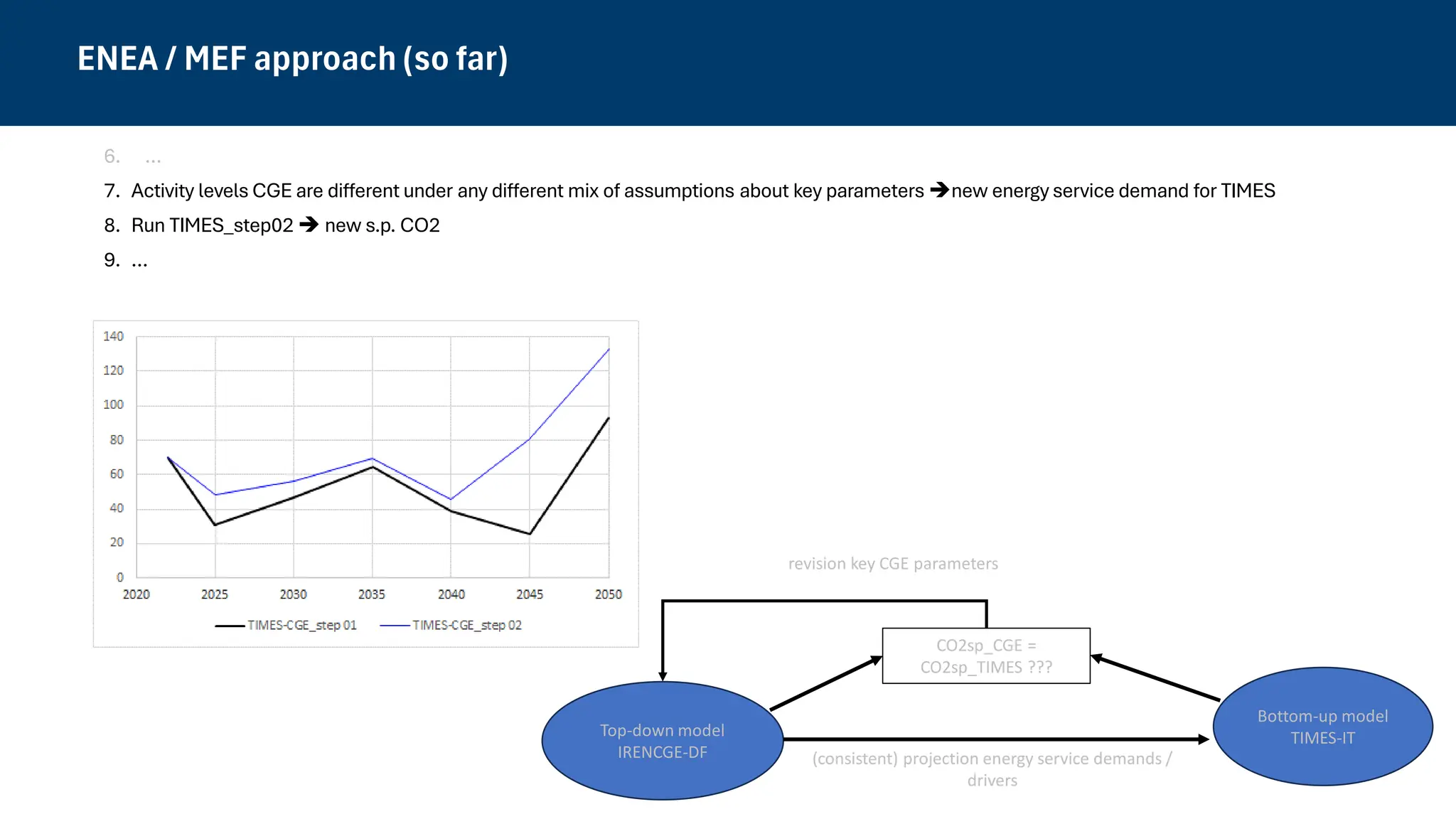

The document discusses the collaboration between ENEA and the Ministry of Economy and Finance (MEF) in Italy to contribute to the OECD's Inclusive Forum on Carbon Mitigation Approaches (IFCMA). It focuses on integrating top-down (CGE) and bottom-up (TIMES) models to enhance the understanding of carbon mitigation policies and their impact on greenhouse gas emissions through a refined methodology. Key phases involve pilot studies, data harmonization, and scenario analyses to model decarbonization pathways towards achieving net-zero emissions by 2050.