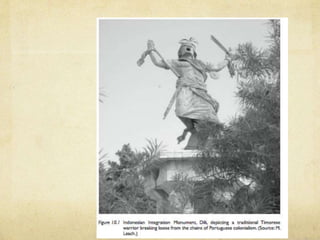

East Timor has a complex cultural heritage formed by its 450 year resistance against foreign occupiers including Portugal, Indonesia, and its current status as an independent nation. This cultural heritage includes memorial sites commemorating independence struggles and human rights abuses under occupation. There is ongoing debate between older and younger generations about how to characterize the nation's identity and historical narrative. East Timor aims to unify its people through preserving diverse aspects of its cultural legacy while acknowledging different experiences of colonialism.