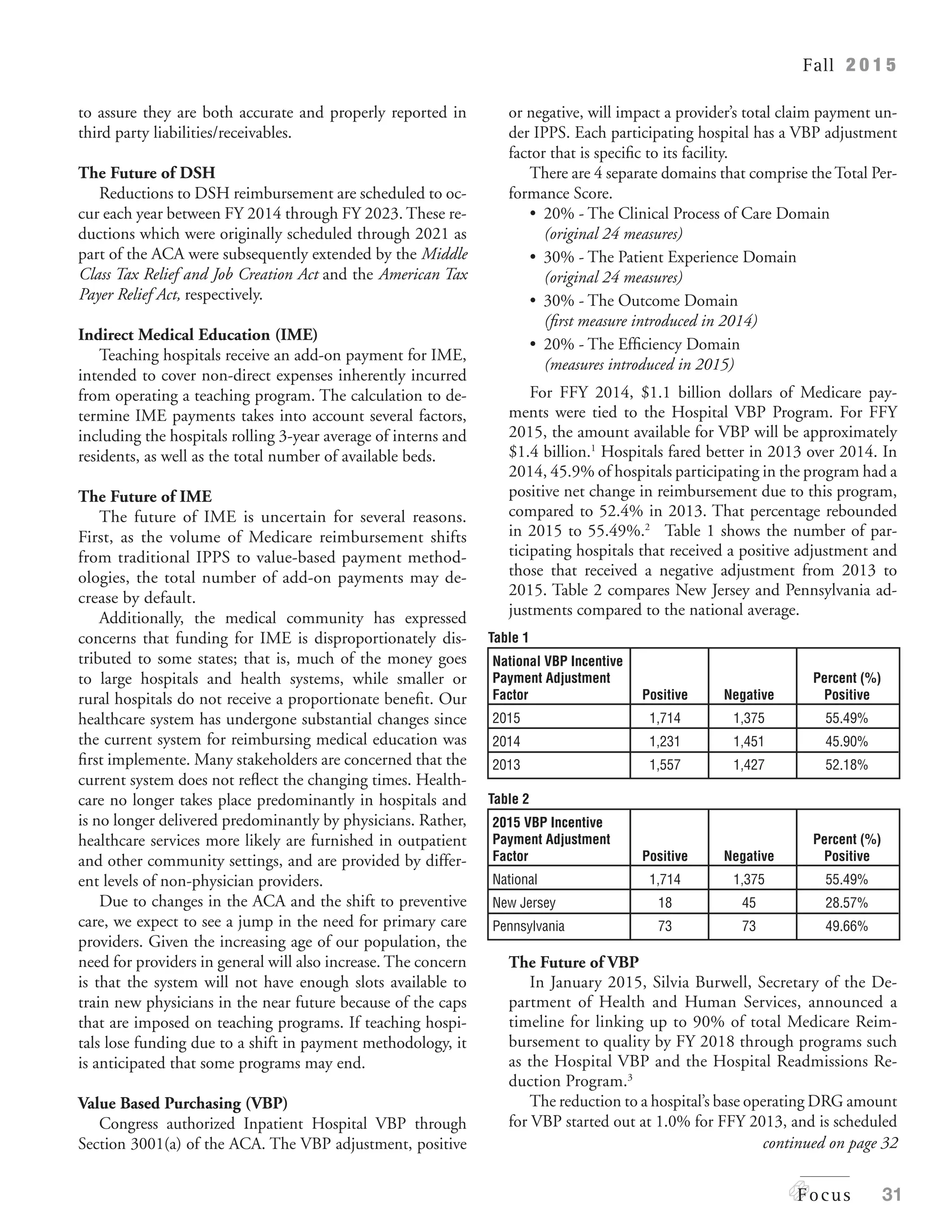

The document discusses the uncertain future of Medicare revenue for hospitals due to changes enacted by the Affordable Care Act and potential payment methodology revisions. Key areas of concern include reductions in Medicare add-ons, bad debt reimbursement, and the implications of value-based purchasing programs on hospital funding. It emphasizes the need for hospitals to monitor their eligibility for these payments and adapt to shifts in the reimbursement landscape.