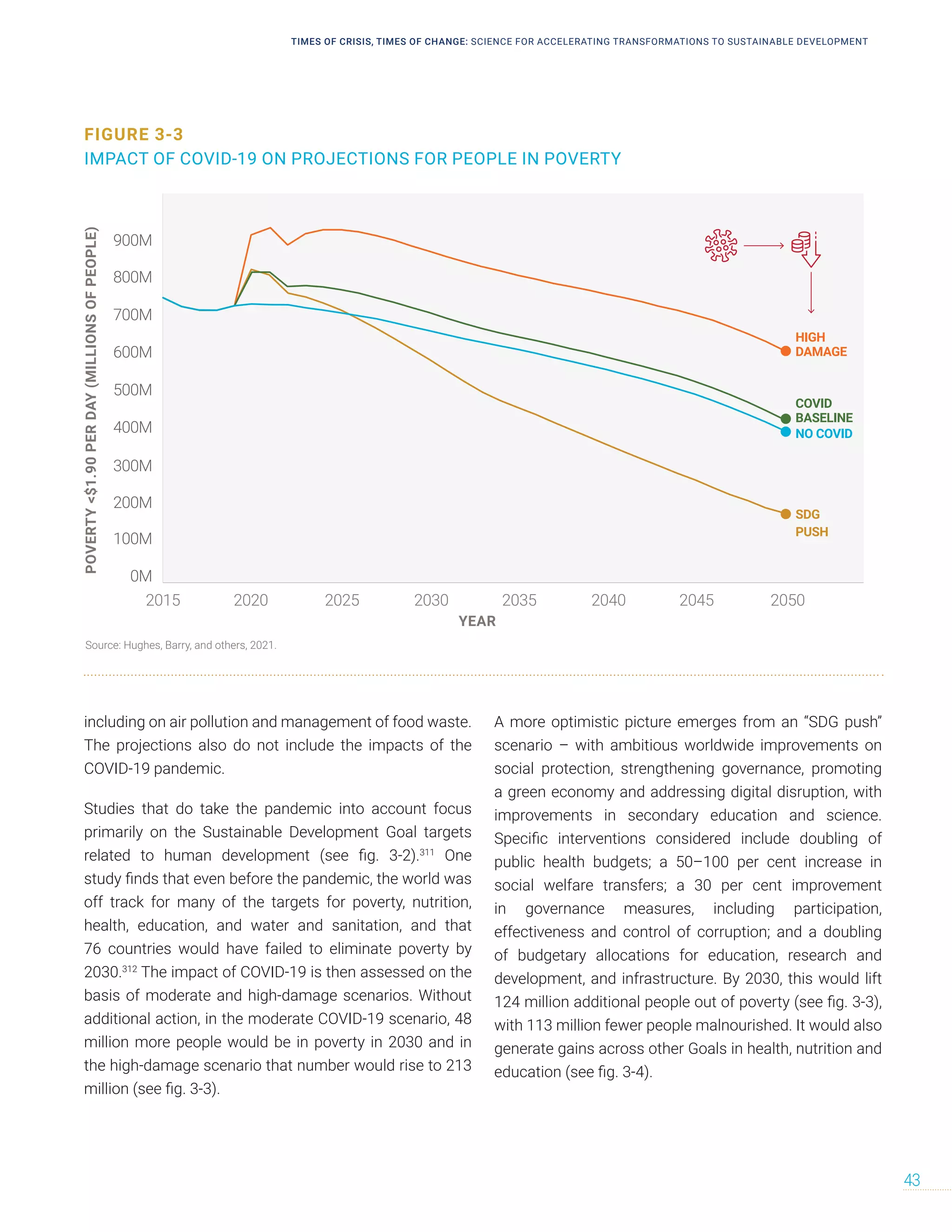

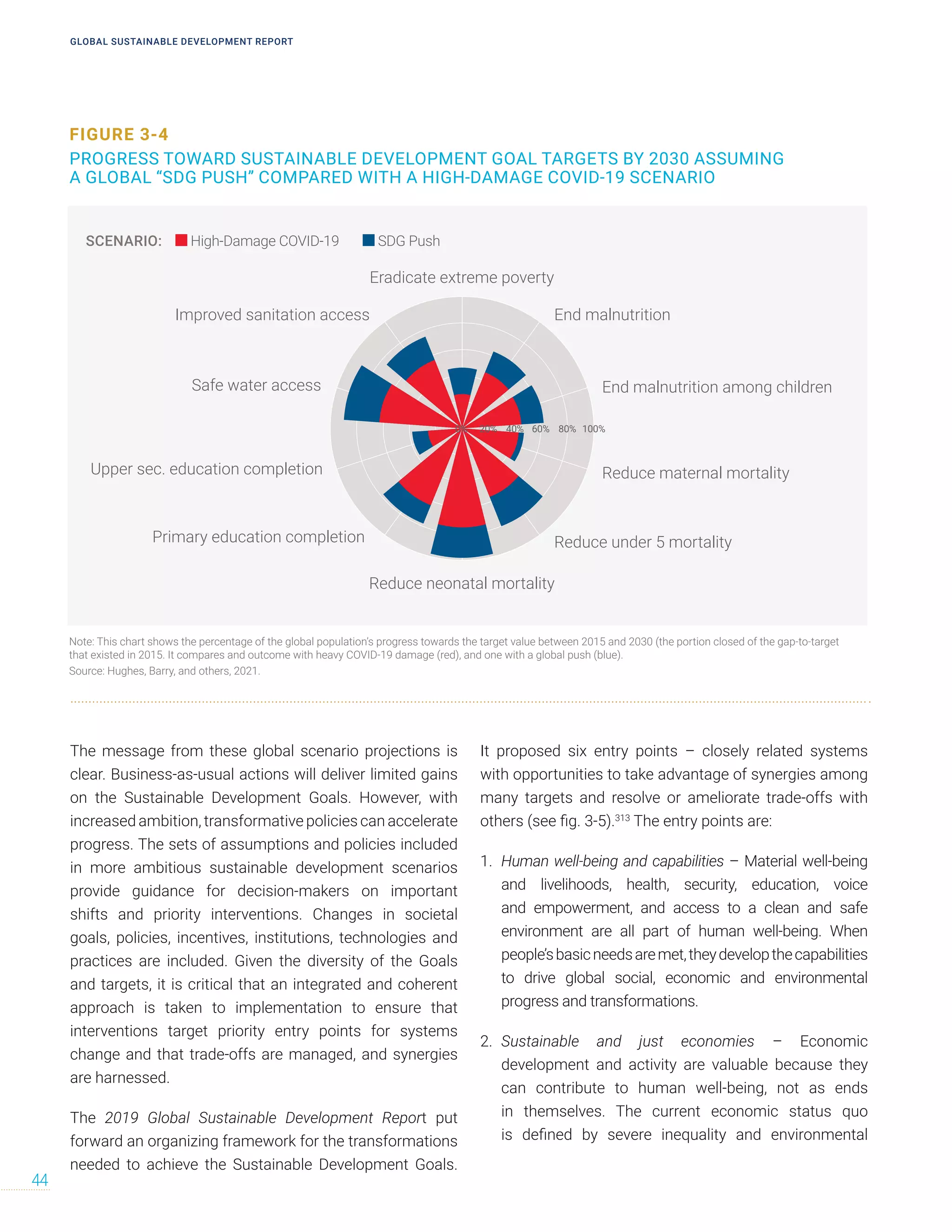

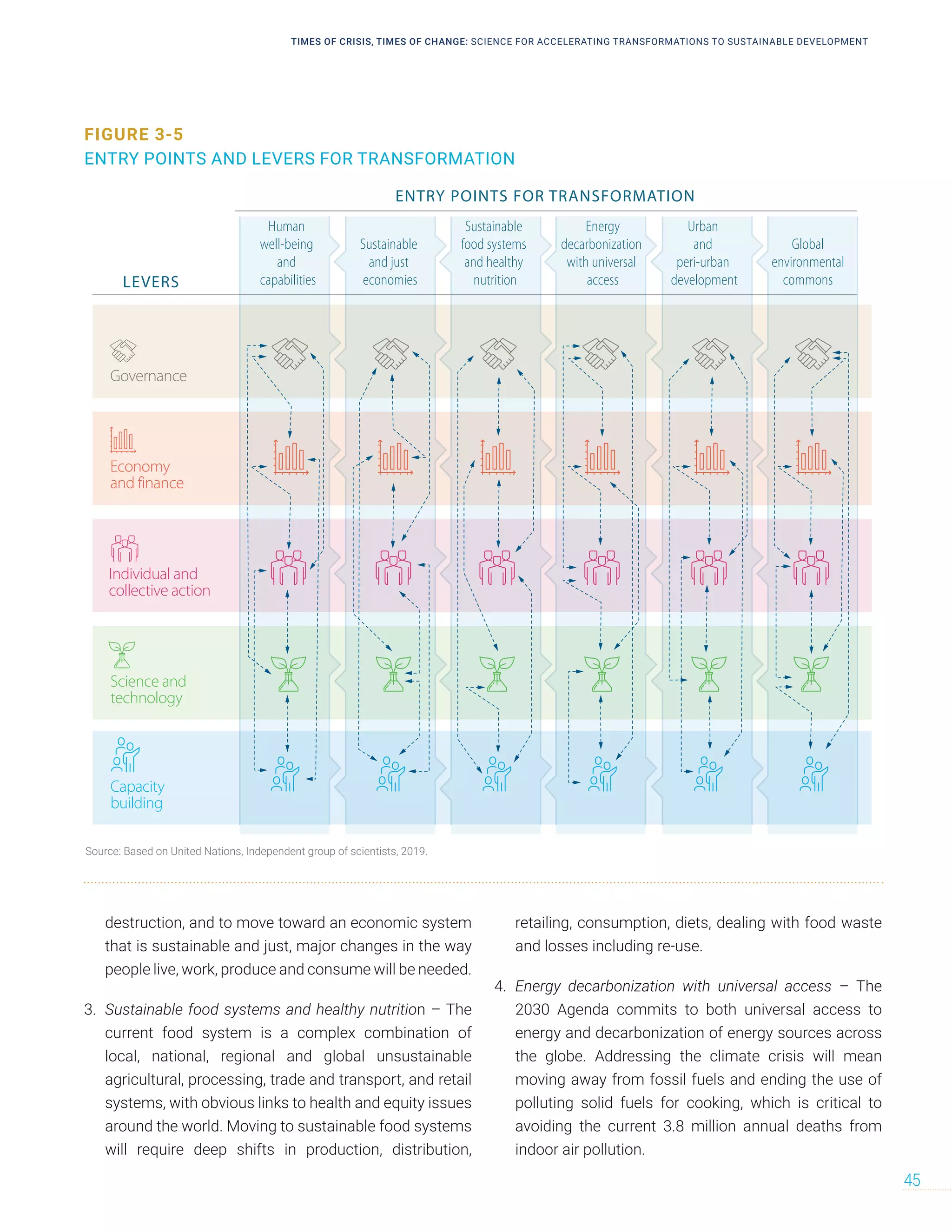

This document is the 2023 Global Sustainable Development Report produced by the Independent Group of Scientists appointed by the UN Secretary-General. It examines progress towards achieving the Sustainable Development Goals and identifies the transformations needed to accelerate progress by 2030. The report finds that while awareness and uptake of the SDGs has increased, the world is off track to meet many of the goals due to insufficient action in the face of ongoing crises like the COVID-19 pandemic, conflicts, and climate change impacts. It outlines pathways, entry points, and interventions that could drive the necessary transformations across sectors like food systems, energy, and the global environmental commons. The report emphasizes the critical role of science in supporting these transformations through multidisciplinary

![TIMES OF CRISIS, TIMES OF CHANGE: SCIENCE FOR ACCELERATING TRANSFORMATIONS TO SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT

115

Beisheim, Marianne, and others. 2022. Global Governance. In: F. Biermann, T. Hickmann and C.-A. Sénit, eds. The

Political Impact of the Sustainable Development Goals: Transforming Governance Through Global Goals? pp. 22-58.

Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

Bello, Ismail. 2020. Sustainable development goals (SDGs) for education in Nigeria: An examination of Etisalat

corporate social responsibility in Nigeria’s post-basic education sector. International Journal of Lifelong Education,

39(5-6): 562-575.

Benedek, Dora, and others. 2021. A Post-Pandemic Assessment of the Sustainable Development Goals. Washington,

D.C., International Monetary Fund.

Bettini, Giovanni, Giovanna Gioli and Romain Felli. 2020. Clouded skies: How digital technologies could reshape

“Loss and Damage” from climate change. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change, 11(4): e650.

Bezjak, Sonja and others. 2018. Open Science Training Handbook (1.0) [Computer software] Zenodo.

Bhutan National Happiness Index. 2023. Bhutan National Happiness Index. Available at

www.grossnationalhappiness.com

Biermann, Frank, Thomas Hickmann and Sénit, Carole-Anne. 2022. The Political Impact of the Sustainable

Development Goals: Transforming Governance Through Global Goals?, Cambridge University Press.

Biermann, Frank, Norichika Kanie and Rakhyun E.Kim. 2017. Global governance by goal-setting: the novel approach

of the UN Sustainable Development Goals Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 26–27: 26-31.

Bill Melinda Gates Foundation. 2022. Goalkeepers: Maternal Mortalit. Available at www.gatesfoundation.org/

goalkeepers/report/2020-report/progress-indicators/maternal-mortality

Bird, Chloe E. 2022. Underfunding of Research in Women’s Health Issues Is the Biggest Missed Opportunity

in Health Care. RAND Corporation.

Bjelle, Eivind Lekve, and others. 2021. Future changes in consumption: The income effect on greenhouse

gas emissions. Energy Economics, 95: 105114.

Bloomberg. 2021. ESG Assets Rising to $50 Trillion Will Reshape $140.5 Trillion of Global AUM by 2025,

Finds Bloomberg Intelligence.

Bogers, Maya, and others. 2022. The impact of the Sustainable Development Goals on a network of 276 international

organizations. Global Environmental Change, 76: 102567.

Bolton, Laura, and James Georgalakis. 2022. The Socioeconomic Impact of Covid-19 in Low- and Middle-Income

Countries, CORE Synthesis Report. Brighton, Institute of Development Studies.

Bowen, Thomas, and others. 2020. Adaptive social protection: building resilience to shocks. World Bank Publications.

Boyce, Daniel G., and others. 2022. A climate risk index for marine life. Nature Climate Change, 12(9): 854-862.

Breuer, Anita, Julia Leininger and Daniele Malerba. 2022. Governance mechanisms for coherent and effective

implementation of the 2030 Agenda: A Cross-National Comparison of Government SDG Bodies. In: A. Breuer, J.

Leininger and D. Malerba, eds. Governing the Interlinkages between the SDGs. London, Routledge.

Broadbent, Gail Helen, and others. 2022. Accelerating electric vehicle uptake: Modelling public policy options on

prices and infrastructure. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice, 162: 155-174.

Brockmeyer, Anne, and others. 2021. Taxing property in developing countries: theory and evidence from Mexico.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/finalgsdr2023-digital-11092311-230913121720-f3819da8/75/The-Global-Sustainable-Development-Report-2023-147-2048.jpg)

![GLOBAL SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT REPORT

124

__________. 2022d. Summary for Policymakers.

__________. 2023. Synthesis Report of the IPCC Sixth Assessment Report.

__________. n.d. Global Warming of 1.5°C: Headline Statements from the Summary for Policymakers.

Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES). 2019. Global

assessment report on biodiversity and ecosystem services of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on

Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services. Bonn, Germany, IPBES Secretariat. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3831673.

__________. 2023. Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services, Available

at https://ipbes.net

Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC). 2022. GRID 2022: Children and youth in displacement.

International Energy Agency (IEA). 2020. Global EV Outlook 2020. Available at www.iea.org/reports/

global-ev-outlook-2020

__________. 2021a. Global Energy Review 2021. Paris.

__________. 2021b. The Role of Critical Minerals in Clean Energy Transitions [World Energy Outlook Special Report].

International Energy Agency.

__________ . 2022a. Global EV Outlook 2022: Securing supplies for an electric future. Available at https://iea.blob.core.

windows.net/assets/ad8fb04c-4f75-42fc-973a-6e54c8a4449a/GlobalElectricVehicleOutlook2022.pdf

__________. 2022b. World Energy Outlook 2022. Paris.

__________. 2022c. CO2 Emissions in 2022.

__________. 2023. Germany’s Renewables Energy Act.

International Labour Organization (ILO). 2017. World social protection report 2017-19: Universal social protection

to achieve the sustainable development goals. ILO.

__________. 2018. World Employment and Social Outlook 2018: Greening with Jobs.

__________. 2021a. Fewer women than men will regain employment during the COVID-19 recovery says ILO.

__________. 2021b. ILO Monitor: COVID-19 and the world of work. Eighth edition. Geneva.

__________. 2022. World Employment and Social Outlook: Trends 2022. Geneva, International Labour Office.

__________. 2023. World Employment and Social Outlook: Trends 2023. Geneva, International Labour Office.

International Monetary Fund (IMF). 2021. Macroeconomic Developments and Prospects in Low-Income Countries.

p. 47. Washington, D.C., International Monetary Fund.

International Organization for Migration (IOM). 2022. World Migration Report 2022. Geneva, International

Organization for Migration.

International Science Council (ISC). 2023. International Network for Governmental Science Advice. Available

at https://ingsa.org

International Telecommunication Union. 2022. Broadband Commission takes aim at closing the digital divide

by 2025. Geneva, ITU.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/finalgsdr2023-digital-11092311-230913121720-f3819da8/75/The-Global-Sustainable-Development-Report-2023-156-2048.jpg)

![GLOBAL SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT REPORT

180

282

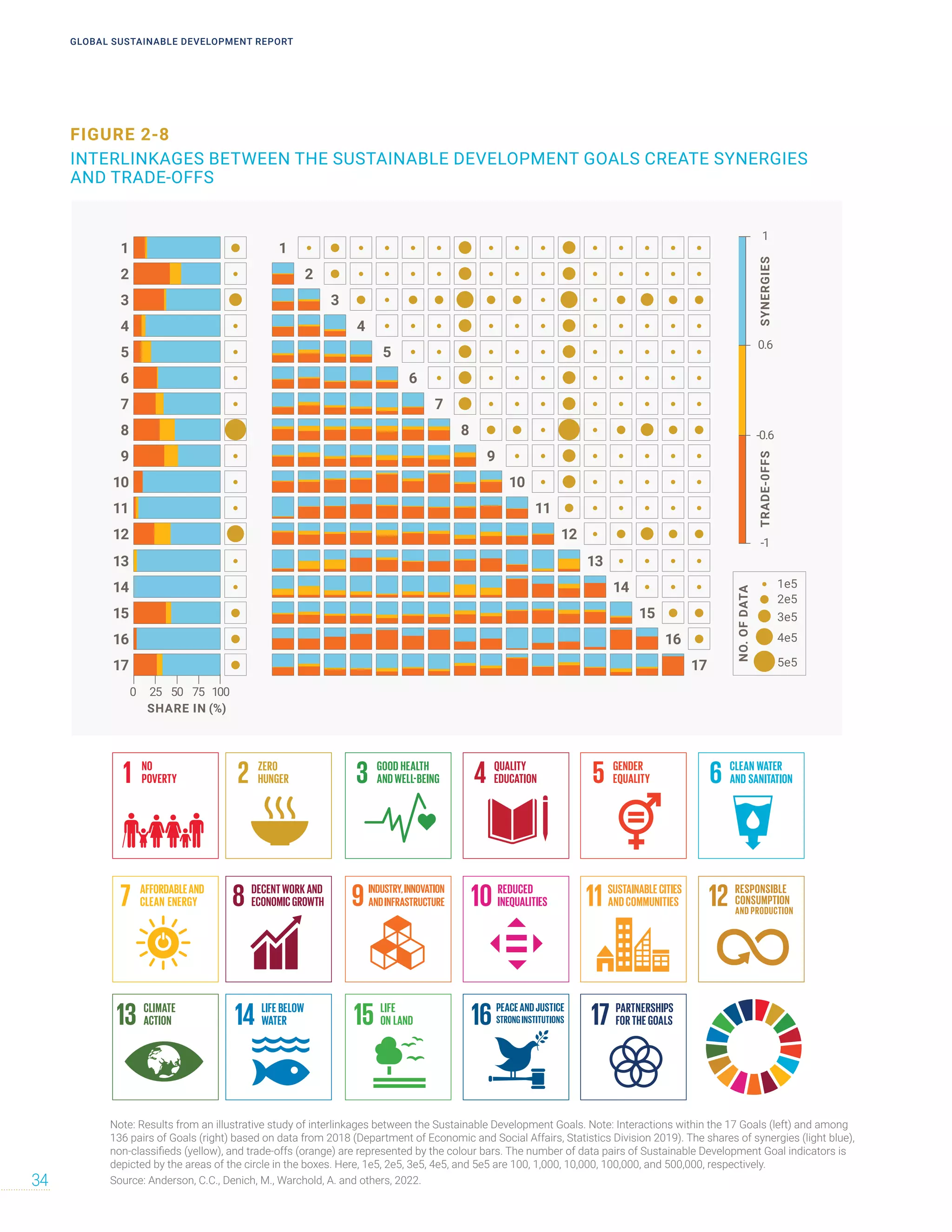

Nilsson, Måns, and others, 2022.

283

Lusseau, David, and Francesca Mancini, 2019.

284

Kostetckaia, Mariia, and Markus Hametner., 2022.

285

Warchold, Anne, Prajal Pradhan and Jürgen P. Kropp., 2021.

286

Bali Swain, Ranjula, and Shyam Ranganathan, 2021; Laumann, Felix, and others, 2022.

287

European Commission, 2021.

288

Morrison-Saunders, Angus, and others, 2020.

289

Barquet, Karina, and others, 2022.

290

OECD, 2019b.

291

OECD, 2019a.

292

OECD, 2019b.

293

Compiled and calculated from OECD data. Available at https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=IO_

GHG_2019#; and World Bank data. Available at https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/BX.GSR.MRCH.CD].

294

OECD and Joint Research Centre, 2021.; Sachs, Jeffrey, and others, 2022b.

295

Sachs, Jeffrey, and others, 2022a.

296

Malik, Arunima, and others, 2021.

297

OECD and Joint Research Centre, 2021.

298

See, for example, the frameworks and spillover categories proposed by Zhao, Zhiqiang, and others, 2021.; OECD

and Joint Research Centre, 2021.

299

European Commission, 2022.

300

Finland, Prime Minister's Office, 2020.; Sweden, 2021.; Kingdom of the Netherlands, 2022.

301

C40 Knowledge Hub. 2022.

302

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, 2022c.

303

O’Neill, B. C., and others, 2017.; Riahi, K., and others, 2017.

304

Riahi, K., and others, 2017.

305

van Vuuren, D.P., and others, 2022.

306

Riahi, K., and others, 2017.; O’Neill, B.C., and others, 2020.

307

O’Neill, B.C., and others, 2020.

308

Soergel, B., and others, 2021a.

309

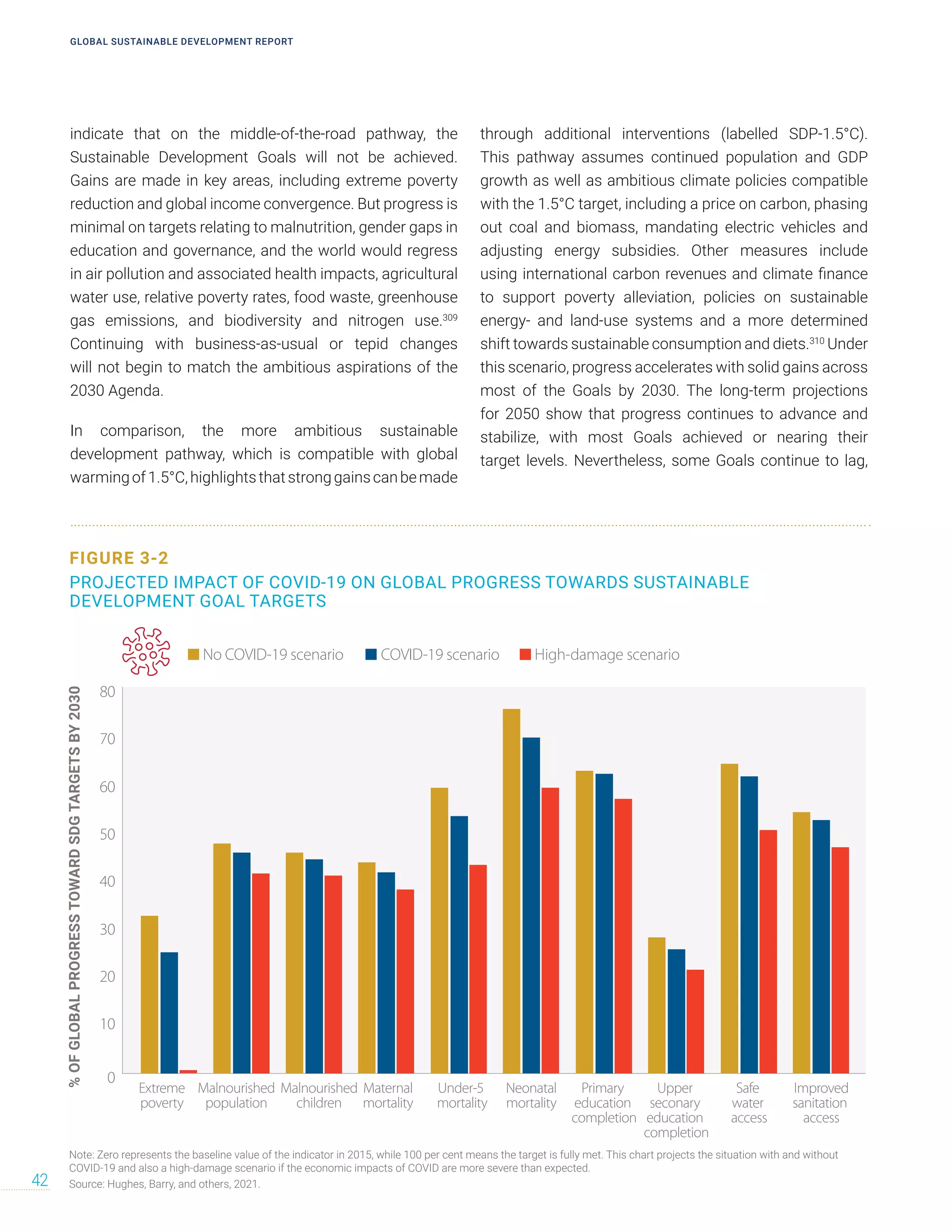

Other studies have come to similarly conclusions. Moyer and Hedden (2020) focus on the ‘human development

targets’ within the SDGs: those for poverty, nutrition, health, education, and water and sanitation. By 2015,

43 per cent of countries had already reached target values, and that by 2030 it was estimated to increase

only to 53 per cent. The study highlights particular difficulties for access to safe sanitation, upper secondary

school completion, and underweight children. It also concluded that 28 countries would not achieve any of

these development related targets, mostly in Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia. These projections do not

incorporate the impacts of COVID-19. Moyer, J. D. and S. Hedden, 2020.

310

Soergel, B., and others, 2021a.

311

Hughes, B., and others. 2020.; Laborde, D., W. Martin and R. Vos, 2021.

312

Hughes, B., and others, 2020.

313

Independent Group of Scientists appointed by the Secretary-General, 2019.

314

Linnér, B.-O. and V. Wibeck, 2021.

315

Meadows, D.H., 1999.

316

Davelaar, D., 2021.

317

Haukkala, T., 2018.

318

Loorbach, D., N. Frantzeskaki and F. Avelino, 2017.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/finalgsdr2023-digital-11092311-230913121720-f3819da8/75/The-Global-Sustainable-Development-Report-2023-212-2048.jpg)