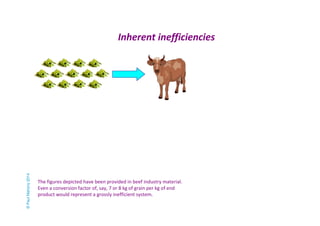

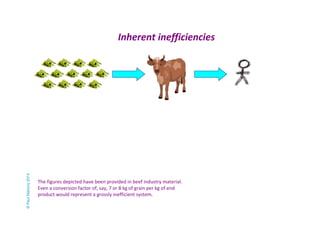

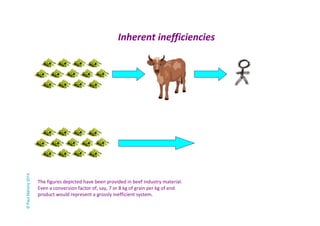

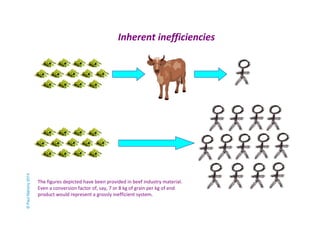

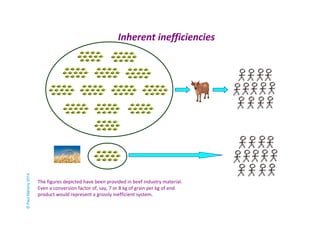

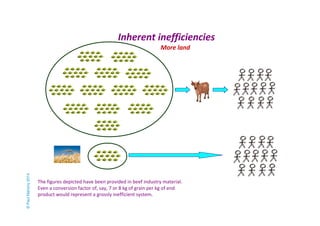

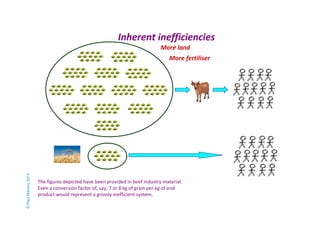

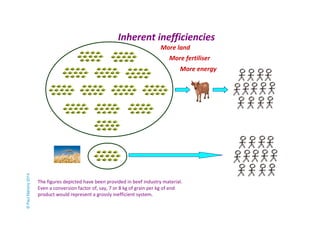

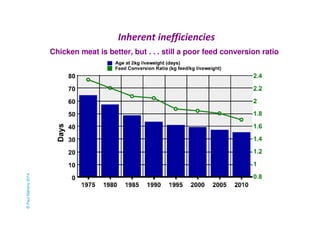

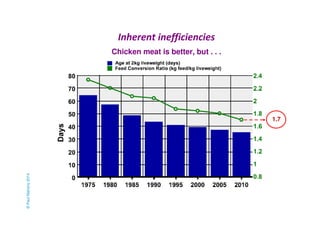

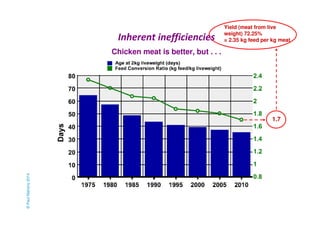

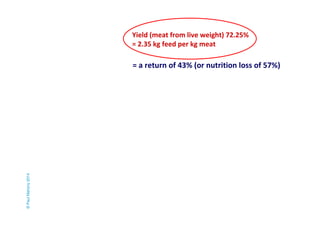

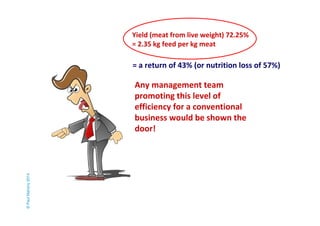

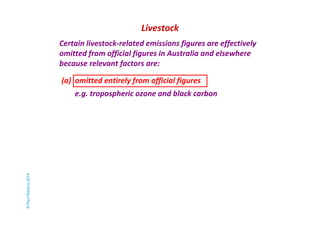

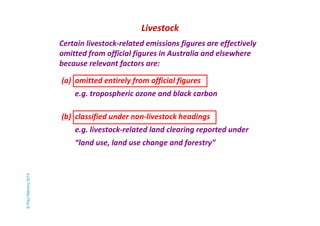

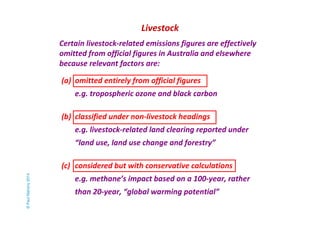

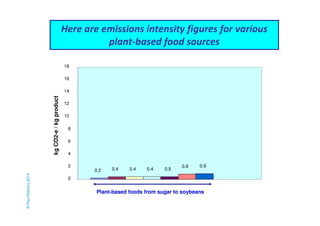

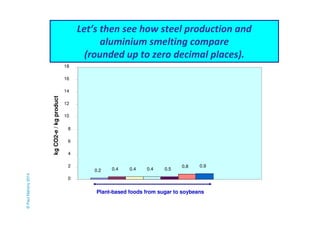

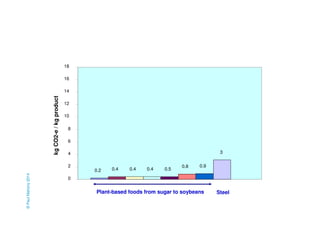

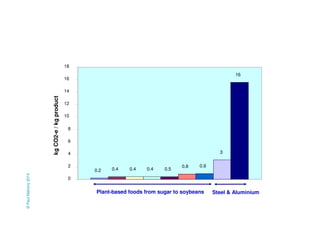

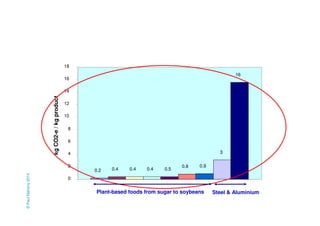

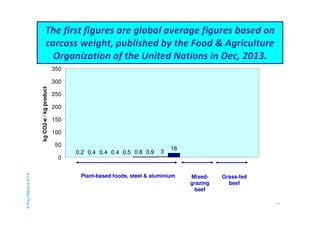

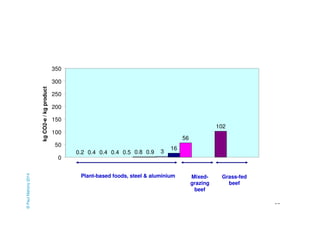

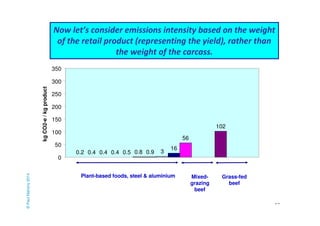

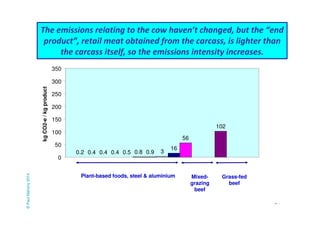

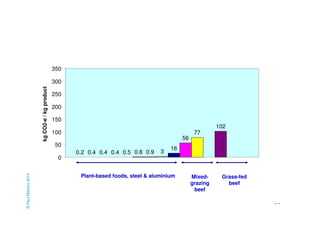

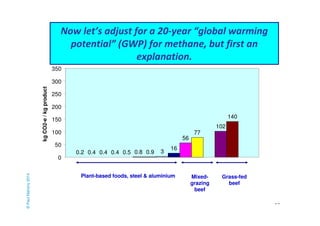

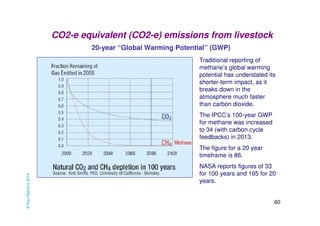

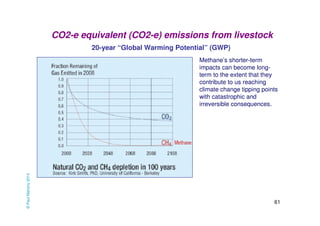

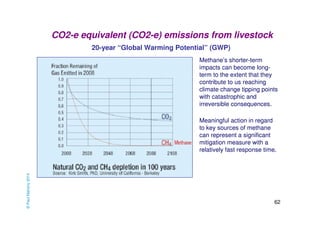

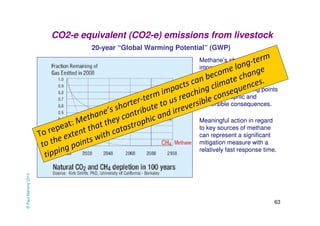

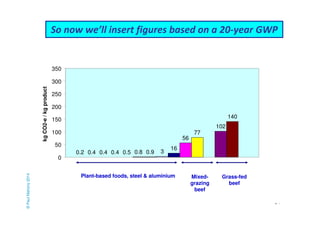

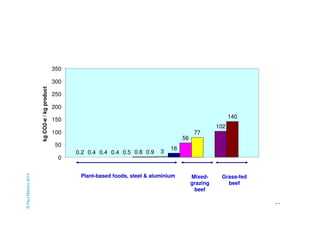

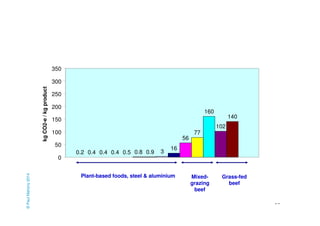

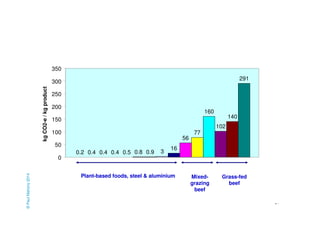

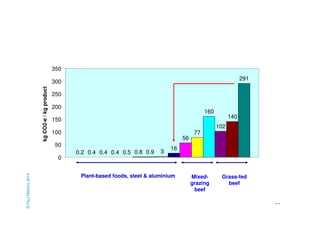

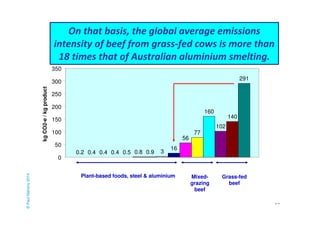

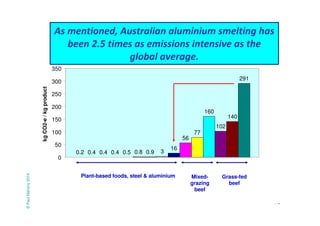

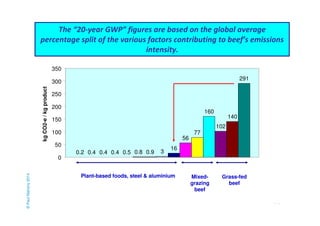

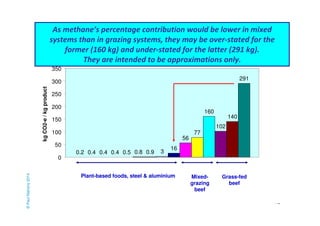

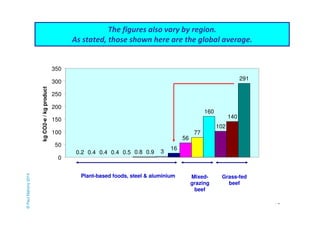

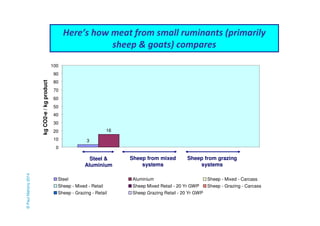

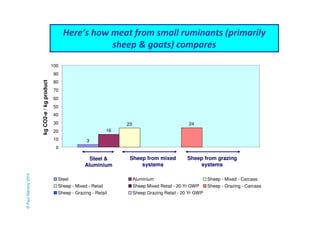

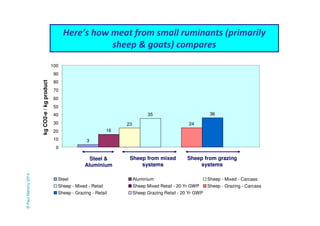

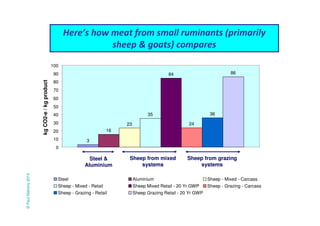

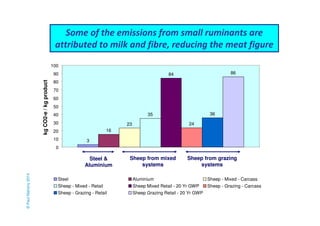

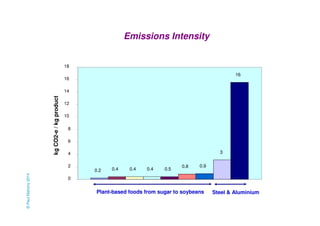

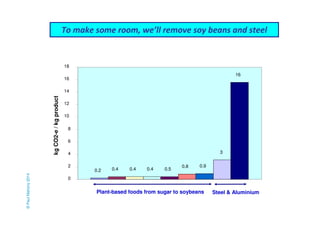

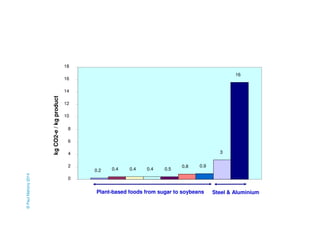

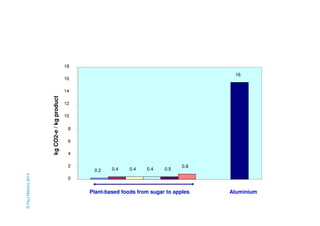

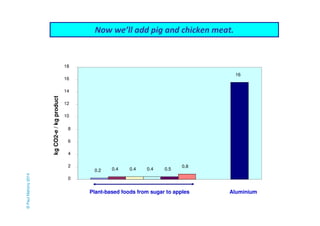

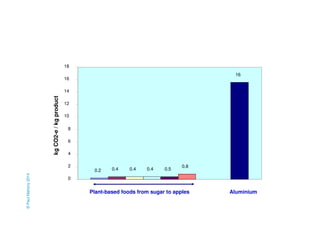

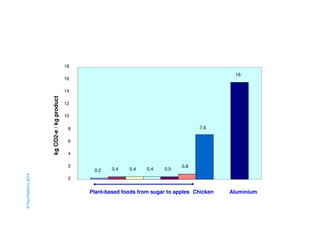

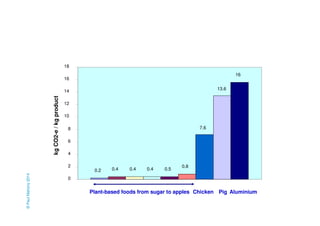

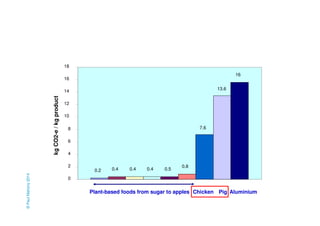

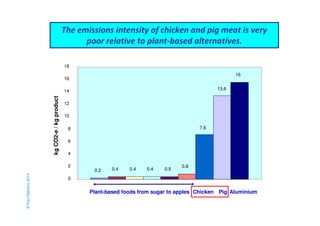

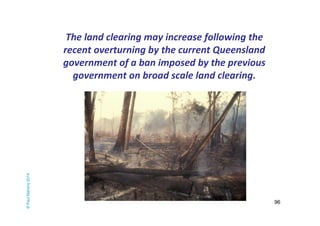

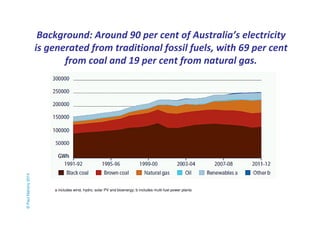

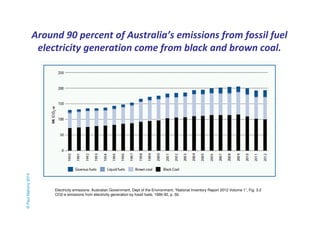

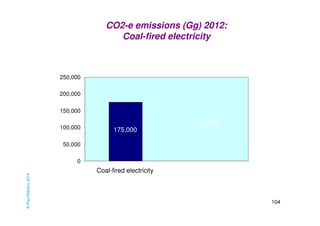

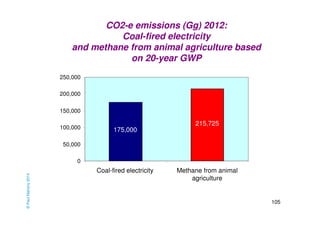

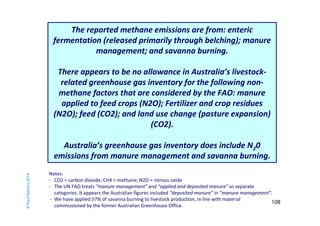

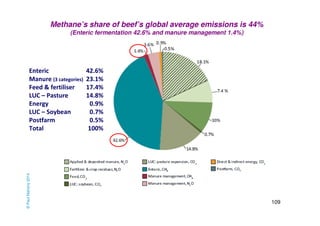

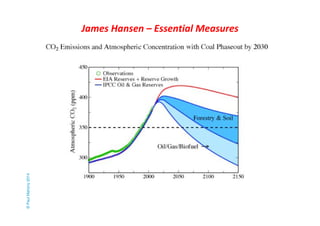

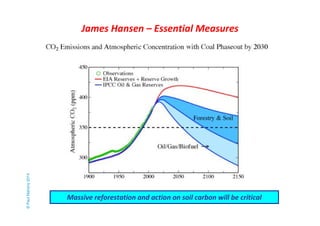

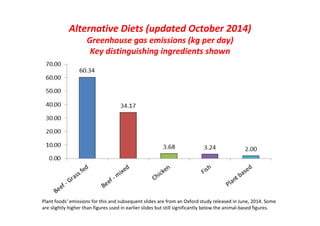

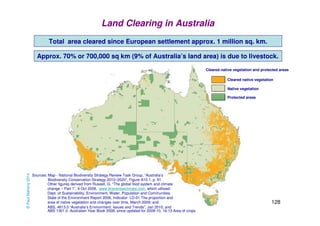

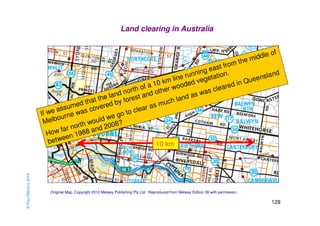

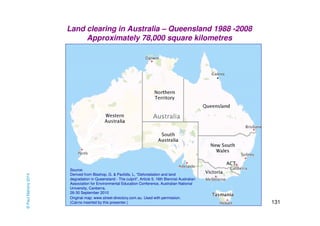

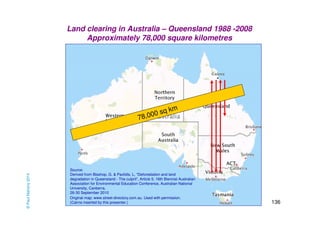

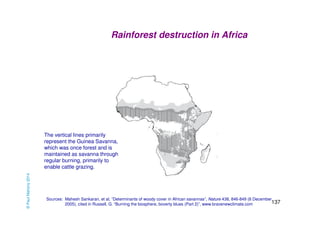

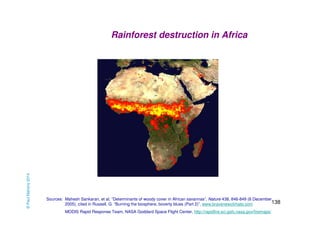

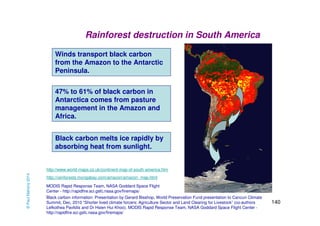

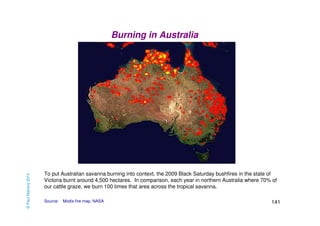

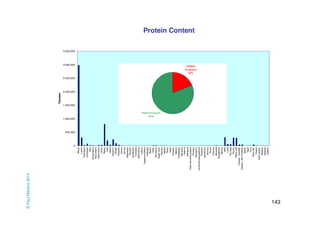

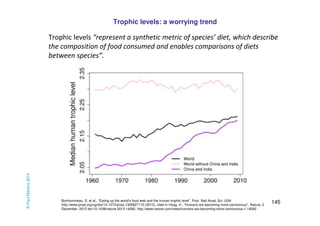

The document examines the inefficiencies in livestock production, particularly focusing on beef, highlighting substantial greenhouse gas emissions and resource usage required to produce meat. It emphasizes the significant environmental impact of the beef industry compared to plant-based food sources and discusses the omitted factors in livestock emissions reporting. Additionally, alternative measures for reducing methane emissions are suggested to mitigate climate change effects.