The document provides an overview of India's Twelfth Five Year Plan (2012-2017). The Plan aims to achieve faster, more inclusive and sustainable economic growth after growth slowed in the previous years. It focuses on immediately reviving investment to return to 9% growth, while also developing capabilities and managing resources rationally for long-term growth potential. Key areas of intervention include capacity building, governance reforms, developing human and institutional resources, managing national resources sustainably, and engaging with the global economy.

![Macroeconomic Framework 43

with 6 per cent achieved in the Eleventh Plan. 2.27. The fixed investment rate fell after 2007–08,

Construction, which grew at 9 per cent in the initially on account of global factors, and later also

Eleventh Plan, is projected to grow at an average owing to difficulties in the domestic arena which

rate of 8.4 per cent, again presumably because of affected the pace of implementation of projects. The

the depressed level at the start of the Plan period. initial estimate for the GFCF rate in 2011–12 at con-

The other service sectors are projected to grow stant prices is 32 per cent. The rate of gross domes-

fairly robustly with Trade Hotels and Restaurants at tic capital formation (GDCF), which includes stocks

8.4 per cent; Transport, Storage and Communication and valuables, but not other errors and omissions,

at 11.8 per cent; Insurance and Business Service at is 37.9 per cent, of which valuables is 2.8 per cent

9.6 per cent, and, finally, Community and Personal of GDP.

Services at 6.7 per cent.

2.28. For annual output growth to average 8.2 per

INVESTMENT cent in the Twelfth Plan period, and to approach

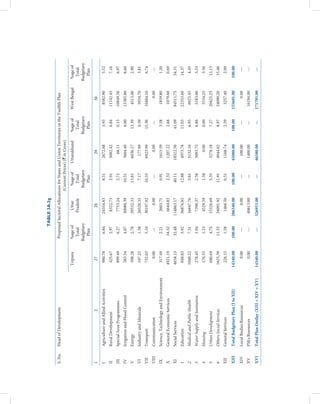

2.26. The ability to raise the rate of investment (ratio 9 per cent in the terminal year, it is estimated that

of gross fixed capital formation [GFCF)] to GDP) the fixed investment rate will have to increase by

is widely regarded as critical for the achievement about 3.0 percentage points of GDP over the level

of high growth. As shown in Figure 2.2, the period in 2011–12. The resulting trajectory of fixed invest-

when the economy grew rapidly after 2003–04 and ment over the Plan period is shown in Table 2.2. The

up to 2007–08 was a period when the investment rate fixed investment rate should increase to 35 per cent

increased. The fixed investment rate rose steadily of GDP (at constant prices) by the end of the Twelfth

after 2003–04 and peaked at close to 35 per cent in Plan, yielding an average fixed investment rate of

2007–08. Total capital formation—which includes 34 per cent of GDP for the Twelfth Plan period as

inventories and investment in valuables—was higher a whole. These levels are marginally higher than

at 39 per cent in that year, but for growth what mat- what was achieved in the Eleventh Plan but they are

ters is the fixed investment. broadly consistent with achieving an average real

35%

30%

25%

20%

15%

10%

1980

1982

1984

1986

1988

1990

1992

1994

1996

1998

2000

2002

2004

2006

2008

2010

2012

FIGURE 2.2: Fixed Investment Rate—Ratio to GDP—Over the Years](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/vol1-130312055349-phpapp02/85/The-12th-Five-year-Plan-Volume-1-49-320.jpg)

![Macroeconomic Framework 53

Prospects for Mobilising External Finance the banking channels was just 0.4 per cent of GDP

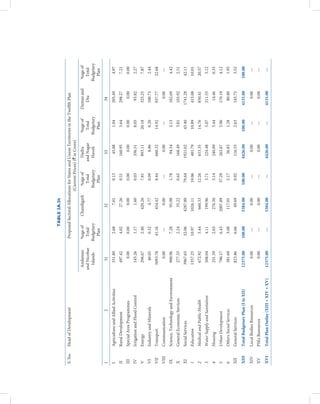

2.59. The capital inflow required to finance a pro- during the course of the Eleventh Plan.

jected average current account deficit of 2.9 per

cent of GDP can take several forms including FDI, 2.63. Total capital inflows from all sources thus

Foreign Institutional Investor (FII) flows, and vari- averaged 4.1 per cent of GDP in the Eleventh Plan

ous types of debt including short-term trade credit period. This volume of capital inflows was signifi-

and official external assistance. Our objective should cantly higher than the financing required for the

be to finance the deficit as much as possible through 2.7 per cent current account deficit, and the excess

stable foreign inflows. This means emphasising FDI was accumulated in the foreign currency assets

and minimising short-term debt in particular. The (including special drawing rights [SDRs] and gold)

pattern of capital flows in the Eleventh Plan period of the Reserve Bank of India (RBI).

and projection for the Twelfth Plan are summarised

in Table 2.3. 2.64. The baseline projections made for the Twelfth

Plan, as presented in Table 2.4, are based on con-

2.60. In the Eleventh Plan, inflows by way of FDI servative assumptions, keeping in mind the cur-

ranged between 1.4 and 2.8 per cent of GDP, averag- rent uncertain conditions in the global economic

ing 2.2 per cent of GDP. In the same period, there environment. This uncertainty is bound to lead to

risk aversion, and also conservative assessment of

were also outflows as Indian companies acquired

the relative attractiveness of India as a destination

overseas assets and this ranged between 1.0 and

for global capital in present circumstances. On this

1.5 per cent in various years, being much higher in

basis, the inbound FDI flows are projected to be

2007–08 and 2008–09, averaging 1.1 per cent for the

slightly less than that in the Eleventh Plan, to average

Eleventh Plan period as a whole. In 2011–12, out-

1.8 per cent of GDP. It is likely that outbound FDI

bound FDI flows were much lower at 0.6 per cent

will also be lower than in the Eleventh Plan level, and

of GDP. The net FDI inflow was thus 1.1 per cent of

is projected to be 0.7 per cent of GDP, and as a result

GDP for the Eleventh Plan as a whole.

the net inflow of FDI will remain almost unchanged

at 1.0 per cent of GDP.

2.61. Portfolio equity inflows fluctuated to a greater

extent, from 1.1–2.4 per cent of GDP in the Eleventh 2.65. Portfolio equity inflows are volatile and given

Plan period, and averaged 1.3 per cent of GDP for the global conditions that have been prevalent for

the Plan period as a whole. It is worth noting that some time, our projections assume that the total of

they were highest at 1.1 per cent in 2008–09, the year such inflows would be only around 0.5 per cent of

immediately after the financial crisis but otherwise GDP, much lower than the 1.3 per cent recorded in

they were positive in every year. This suggests that the Eleventh Plan. This assumption is almost cer-

while FII flows are more volatile, than FDI, they are tainly unduly cautious. Early resolution of some

not the same as ‘hot money’. of the uncertainties that have arisen in the mind of

foreign investors in India, combined with a visible

2.62. Loan capital inflows occur mostly through resumption of growth momentum in 2013–14, could

external commercial borrowings (ECBs) of Indian easily lead to stronger inflows in the remaining years.

private and public sector companies and non- An average of 1 per cent of GDP over the Plan period

resident bank deposits. Short-term trade loans as is not at all infeasible.

well as FII investment in Indian government and

corporate debt securities are also significant. Net 2.66. Loan and banking capital inflows, net of repay-

inbound official assistance now forms a relatively ments, taken together are expected to be 1.7 per cent

small component of capital inflows. These sources of GDP, lower than that the 1.9 per cent recorded in

taken together accounted for 1.5 per cent of GDP in the Eleventh Plan. Taking all the flows together, the

the course of the Eleventh Plan. Net inflow through total of capital inflows in the Twelfth Plan is expected](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/vol1-130312055349-phpapp02/85/The-12th-Five-year-Plan-Volume-1-59-320.jpg)

![Sustainable Development 119

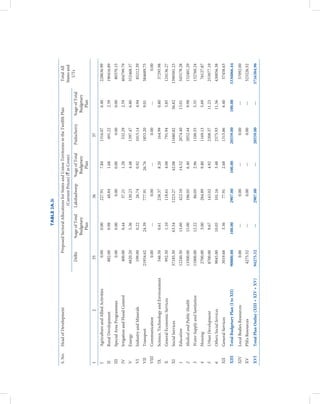

Box 4.2

Importance of Clean Coal Technology: Ultra-super Critical Power Plants

An Ultra Super Critical (USC) coal-based power plant has an efficiency of 46 per cent compared with 34 per cent for a sub

critical plant and 40 per cent for a Super Critical (SC) plant. Thus, with an USC or SC plant, the savings in coal consumption

and reduction in CO2 emission can be substantial. A 10,000 MW power plant will generate 60 billion units of electricity per

year at around 70 per cent load factor. It has a specific heat of 1870 kcal/kwh compared to 2530 kcal/kwh for a sub-critical

plant. Thus, every unit generated with USC will save 0.165 kg [(2530-1870)/4000] coal of 4000 kcal/kg; and 60 billion units

will save 9.9 million tonnes of coal per year.

When we substitute a sub-critical coal plant with solar plants, for every kwh generated we save 0.63 kg of coal (2530/4000).

Thus, 15.6 billion units (1000*9.9/0.63) will have to be generated by solar plants to save the equivalent 9.9 million tonnes

of coal. Since a solar plant generates 1500 units per KW of installed capacity, the matching installed capacity needed will be

nearly 100,000 MW (15.6*1000/15000). To put it simply, faster adoption of USC and SC technology can save as much coal as

would be saved by installation of ten times the solar power capacity. While from a long term perspective we need the solar

option, from a medium term perspective, development of USC and SC technology should be pursued vigorously.

also requires the development of special materi- increases the power generation potential. At the

als that can withstand high temperatures and pres- same time, the size of wind turbines has increased—

sures. The government should support research and while the earlier turbines were typically less than

development to promote indigenous manufacturing 1 MW, the recent designs go up to over 5 MW. Taking

of USC units. The first USC plant, which is a joint these into consideration, the wind potential in India

effort of BHEL, NTPC and IGCAR, is expected to is now estimated at about 103000 MW for 80 m hub

be operational in 2017. Deployment of USC plants height. This is based on meso-scale weather models

may be suitably incentivised and targeted during the and a land utilization rate at 2 per cent thought to be

Thirteenth Plan period. reasonable for Indian conditions. Some recent stud-

ies have estimated India’s wind potential to be over

4.37. Coal gasification provides opportunities for 500000 MW based on still higher hub heights and

higher efficiency. However, Indian coal has very high more land availability. However, this assessment is

ash content and initial results suggest that efficiency yet to be validated by experts working under Indian

gain over sub-critical units is only marginal. Under- conditions.

ground coal gasification is an important technol-

ogy since it enables utilisation of deep coal deposits, 4.39. Recent technological innovations, including

which cannot be mined using conventional means raising the height of the tower, could make wind a

or because they are located in environmentally frag- major renewable source of power generation for

ile regions. It also allows the possibility of in situ India and we could safely target a wind capacity

carbon capture. Given India’s coal shortage, there addition of 30000 MW by 2020. However, as noted

should be greater research in this technology, includ- in Chapter 12, wind potential is unevenly distributed

ing execution of a few pilot projects. Another poten- across the country; only Karnataka, Tamil Nadu,

tially promising technology is coal bed methane and Andhra Pradesh, Maharashtra and Gujarat have

it may be desirable to undertake some pilot action in significant potential. Therefore, realisation of wind

this regard. potential requires careful regional level planning and

coordination.

Wind Power

4.38. India has a potentially large capacity for adding 4.40. Wind power has significant seasonal and even

generation capacity based on wind power. Since, the intra-day variations. Therefore, setting targets for

power generated by a wind turbine is highly sensitive wind power capacity addition, without making a

to wind speeds, the global practice is now to build careful assessment of the capacity of the regional grid

towers in the range of 80–120 m, which significantly to balance its intermittency with alternative sources,](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/vol1-130312055349-phpapp02/85/The-12th-Five-year-Plan-Volume-1-125-320.jpg)

![176 Twelfth Five Year Plan

because of the lack of capabilities and understanding landowner the right to take substantially as much

at lower levels of the institutional ladder is sought groundwater as she or he desires from wells dug

to be taken care of through the concept of phased on own land. Landowners do not own ground-

institutional transition by providing step-wise, gate- water but enjoy access as part and parcel of their

protected processes for gradual introduction of the ownership rights to the land above:

decentralised institutional structure.

The person who owns the surface may dig

5.146. The Bill also builds in enough flexibility in therein, and apply all that is there found to

its design to take care of differences across States his own purposes at his free will and plea-

through a modular structure, from which modules sure; and that if, in the exercise of such right,

based on the state-specific situation, requirements, he intercepts or drains off the water collected

priorities of water sector governance, and other fac- from underground springs in his neighbour’s

tors could be selected by the state government while well, this inconvenience to his neighbour falls

preparing and enacting their final draft of the Bill. within the description of damnumabsquein-

juria [damage without injury], which cannot

NEW GROUNDWATER LAW29 become the ground of an action.30

5.147. Since sustainable and equitable management

of groundwater based on aquifer management is • Defined vs Undefined channels: ‘Groundwater

going to occupy centre-stage, this requires a new that percolates through underground strata,

legal framework to support efforts in this direction. which has no certain course, no defined limits,

but which oozes through the soil in every direc-

Limitations of the Present Legal Framework tion in which the rain penetrates is not subject to

for Groundwater the same rules as flowing water in streams or riv-

5.148. As early as the 1970s, the GoI put forward a ers.’29 On the other hand, where groundwater was

model bill to regulate groundwater use for adoption found to flow in defined channels, case law says

by the States. This model bill has been revised several that rules applicable to surface water would also

times (1992, 1996 and 2005) but the basic scheme apply. This has been interpreted30 to mean that the

adopted in the 1970s has been retained to date. The right of the landowner would then be limited to

Model Bill to Regulate and Control the Development use and consumption for household and drinking

and Management of Ground Water, 2005 only intro- purpose, for watering their cattle and even for irri-

duces a limited regulatory framework to address gating their land or for purposes of manufacture

groundwater depletion and pollution and amounts provided that

to little more than ‘grandfathering’ existing uses.

− the use is reasonable;

5.149. Rules concerning access to and use of ground- − it is required for their purposes as owners of

water in India have been progressively developed the land and

through judicial decisions. What is remarkable is − it does not destroy or render useless or mate-

that some of the most important legal principles rially diminish or affect the application of the

governing groundwater even today were laid down water by riparian owners below the stream in

in British common law as early as the middle of the the exercise either of their natural right or right

nineteenth century and have not been updated since. of easement, if any.

These legal principles are:

5.150. A lot of legal hermeneutics was devoted

• Landowners given full control of groundwater: over the years to clearly spelling out the distinction

Existing rules of access to and control over between defined and undefined channels of ground-

groundwater are still based on the common law water.31 The difficulty, of course, is that this differ-

doctrine of absolute dominion. This gives the entiation is completely meaningless in scientific](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/vol1-130312055349-phpapp02/85/The-12th-Five-year-Plan-Volume-1-182-320.jpg)