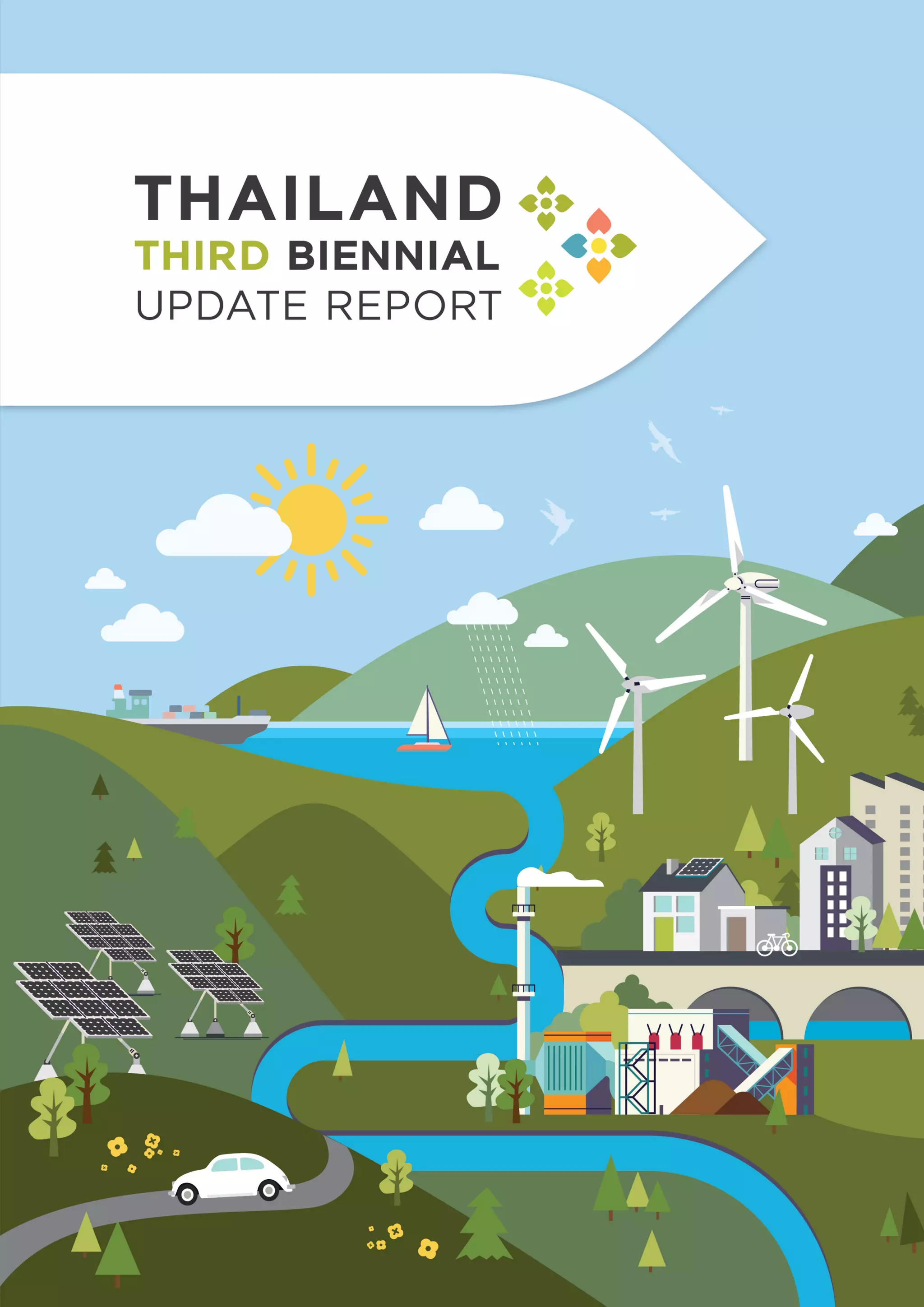

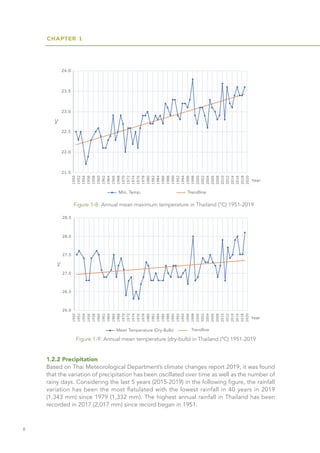

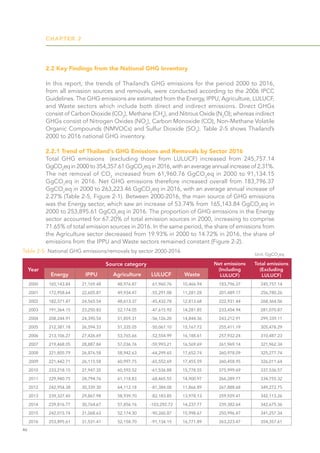

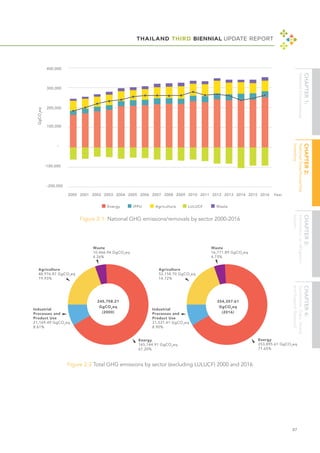

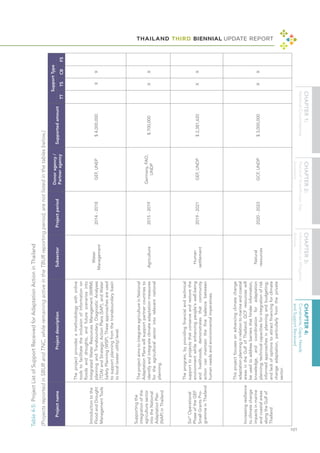

This document provides information on Thailand's Third Biennial Update Report (BUR), including contributors and contents. It lists government ministries and organizations that were involved in developing the report. The report contents include 4 chapters that discuss: 1) national circumstances, 2) national greenhouse gas inventory, 3) information on mitigation actions, and 4) constraints, gaps, needs and support received. It provides an overview of the report's purpose in presenting Thailand's efforts to address climate change in accordance with UNFCCC guidelines.