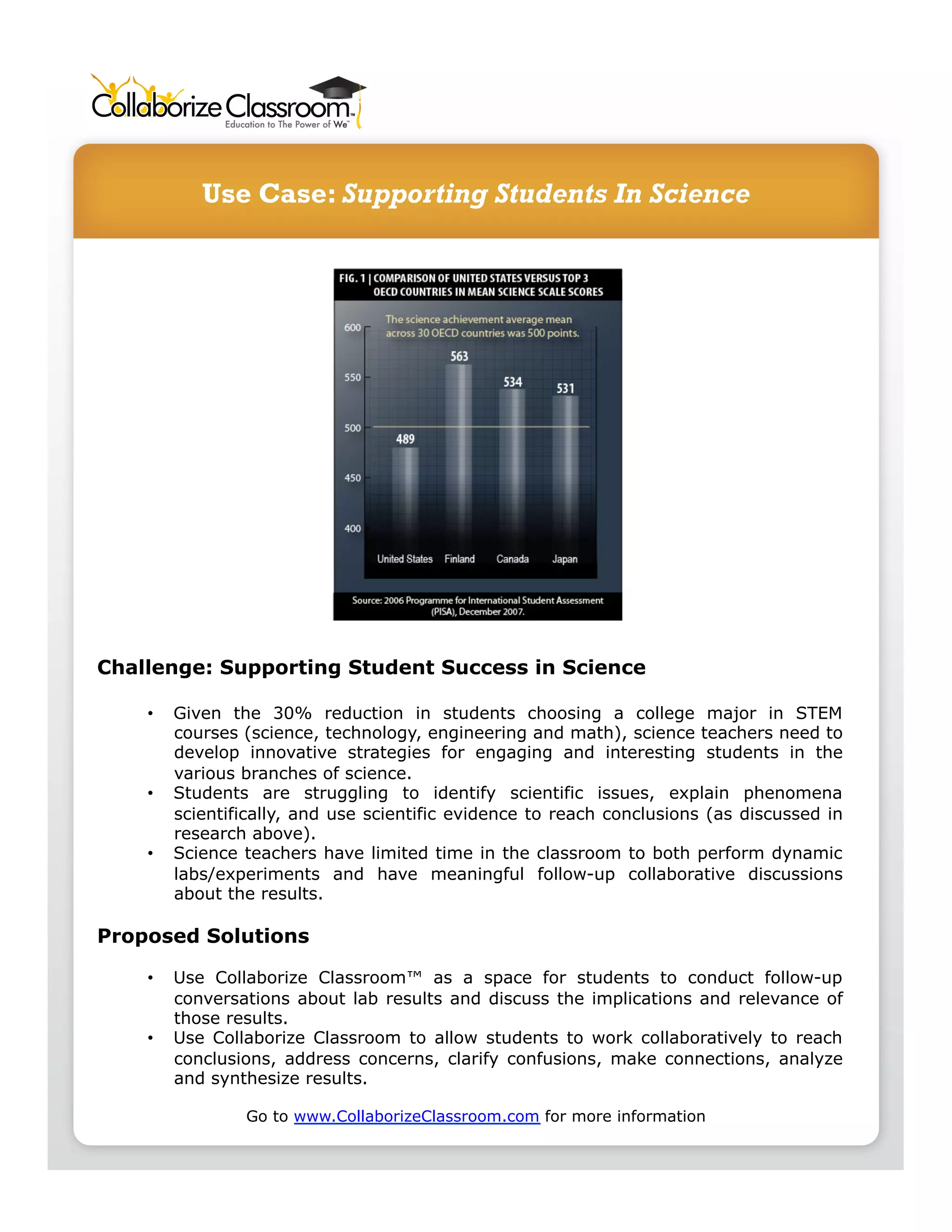

The document discusses the PISA 2006 science literacy assessment, highlighting that U.S. students scored lower in science literacy compared to many other jurisdictions. It suggests that innovative strategies are needed to engage students in science, given the declining interest in STEM fields. Proposed solutions include using Collaborize Classroom for collaborative discussions, follow-up on lab results, and facilitating meaningful interactions that enhance students' understanding of scientific principles.