Isomerism in polymers, stemming from stereoisomerism during polymerization, significantly affects polymer properties, with early recognition of this phenomenon leading to advancements in synthesizing highly stereoregular polymers. Pioneering work by Ziegler and Natta highlighted methods for producing such polymers, which are common in nature and have vast commercial applications. The document discusses the various types of stereoisomerism, including cis-trans and enantiomers, along with the implications of tacticity on polymer configurations.

![representations on the far right side of Fig. 8-1, recommended by IUPAC [1981], are obtained

by rotating the previous Fischer projections 90degree counterclockwise. The resulting Fischer

projections do have the advantage of showing the polymer chain going in the same direction as

the far-left representations. Their disadvantage is that one must always keep in mind that the

usual Fischer convention for horizontal (forward) and vetical (back) bonds is reversed. These

rotated Fischer projections will be used in the remainder of this chapter. The Fischer

projections show that isotactic placement corresponds to meso or m-placement for a pair of

consecutive stereocenters. Syndiotactic placement corresponds to racemo (for racemic) or r-

placement for a pair of consecutive stereocenters.

The configurational repeating unit is defined as the smallest set of configurational base units

that describe the configurational repetition in the polymer. For the isotactic polymer from a

monosubstituted ethylene, the configurational repeating unit and configurational base unit are

the same. For the syndiotactic polymer, the configurational repeating unit is a sequence of two

configurational base units, an R unit followed by an S unit or vice versa. Polymerizations that

yield tactic structures (either isotactic or syndiotactic) are termed stereoselective

polymerizations. The reader is cautioned that most of the literature uses the term

stereospecific polymerization, not stereoselective polymerization. However, the correct term is

stereoselective polymerization since a reaction is termed stereoselective if it results in the

preferential formation of one stereoisomer over another. This is what occurs in the

polymerization. A reaction is stereospecific if starting materials differing only in their

configuration are converted into stereoisomeric products. This is not what occurs in the

polymerization since the starting material does not exist in different configurations. (A

stereospecific process is necessarily stereoselective but not all stereoselective processes are

stereospecific.) Stereoselective polymerizations yielding isotactic and syndiotactic polymers are

termed isoselective and syndioselective polymerizations, respectively. The polymer structures

are termed stereoregular polymers. The terms isotactic and syndiotactic are placed before the

name of a polymer to indicate the respective tactic structures, such as isotactic polypropene

and syndiotactic polypropene. The absence of these terms denotes the atactic structure

polypropene means atactic polypropene. The prefixes it- and st- together with the formula of

the polymer, have been suggested for the same purpose: it-[CH2CH(CH3)]n and st-[CH2

CH(CH3)]n.

Both isotactic and syndiotactic polypropenes are achiral as a result of a series of mirror planes

(i.e., planes of symmetry) perpendicular to the polymer chain axis. Neither exhibits optical

activity.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/stereochemistry1-240729115143-56d4da5c/85/Stereochemistry_1-pptx-4-320.jpg)

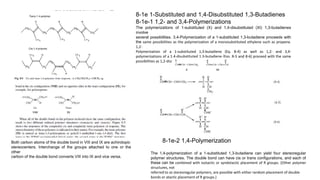

![The all-trans–all-isotactic and all-trans–all-syndiotactic structures for the 1,4-

polymerization

of 1,3-pentadiene are shown in Fig. 8-6. In naming polymers with both types of

stereoisomerism, that due to cis–trans isomerism is named first unless it is indicated

after the prefix poly. Thus, the all-trans–all-isotactic polymer is named as transisotactic

1,4-poly(1,3-pentadiene) or isotactic poly(E-3-methylbut-1-ene-1,4-diyl).

The sp3 stereocenter (i.e., C*) in XII is chirotopic, like the case of poly(propylene oxide),

since the first couple of atoms of the two chain segments are considerably different.

The isotactic structures are optically active while the syndiotactic structures are not

optically active.

The 1,4-polymerization of 1,4-disubstituted 1,3-butadienes leads to structure (XIII),

which can exhibit tritacticity since the repeating unit contains three sites of steric

isomerism—a double bond and the carbons holding R and R’ substituents.

Several different stereoregular polymers are possible with various

combinations of ordered arrangements at the three sites. For example,

polymer XIV possesses an erythrodiisotactic arrangement of and R0 groups

and an all-trans arrangement of the double bonds. The polymer is named

transerythrodiisotactic 1,4-poly(methyl sorbate) or diisotactic poly[erythro-3-

(methoxycarbonyl)- 4-E-methylbut-1-ene-1,4-diyl].

All four diisotactic polymers (cis and trans, erythro and threo) are chiral and

possess optical activity. Each of the four disyndiotactic polymers possesses a

mirror glide plane and is achiral. For symmetric 1,4-disubstituted 1,3-butadienes

(R =R’), only the cis and transthreodiisotactic structures are chiral. Each of the

erythrodiisotactic and threodisyndiotactic polymers has a mirror glide plane.

Each of the erythrodisyndiotactic polymers has a mirror glide plane.

8-1f Other Polymers

The polymerization of the alkyne triple bond (Secs. 5-7d and 8-6c) and ring-

opening metathesis polymerization of a cycloalkene (Secs. 7-8 and 8-6a) yield

polymers containing double bonds in the polymer chain. Cis–trans isomerism is

possible analogous to the 1,4-polymerization of 1,3-dienes.

Polymers containing rings incorporated into the main chain (e.g., by double-

bondpolymerization of a cycloalkene) are also capable of exhibiting stereoisomerism.

Such polymers possess two stereocenters—the two atoms at which the polymer chain

enters and leaves each ring. Thus the polymerization of cyclopentene to

polycyclopentene [IUPAC: poly(cyclopentane- 1,2-diyl)] is considered in the same

manner as that of a 1,2-disubstituted ethylene. The four possible stereoregular

structures are shown in Fig. 8-7. The erythro polymers are those in which there is a cis

configuration of the polymer chain bonds entering and leaving each ring; the threo

polymers have a trans configuration of the polymer chain bonds entering and leaving

each ring. The threodiisotactic structure is chiral while the other three structures are

achiral. The situation is different for an asymmetric cycloalkene such as 2-

methylcyclopentene where both diisotactic structures are chiral, while both

disyndiotactic structures are achiral.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/stereochemistry1-240729115143-56d4da5c/85/Stereochemistry_1-pptx-9-320.jpg)