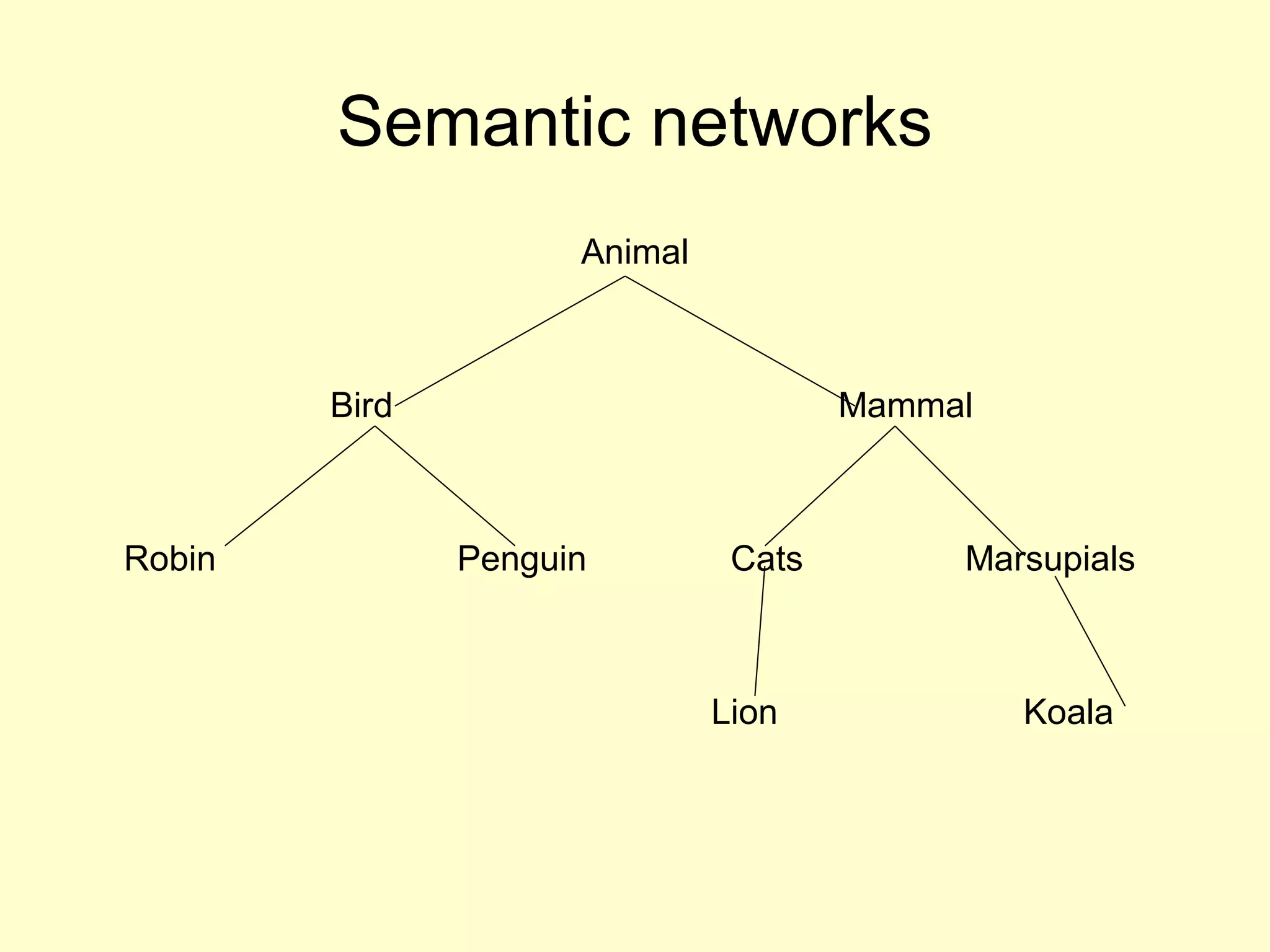

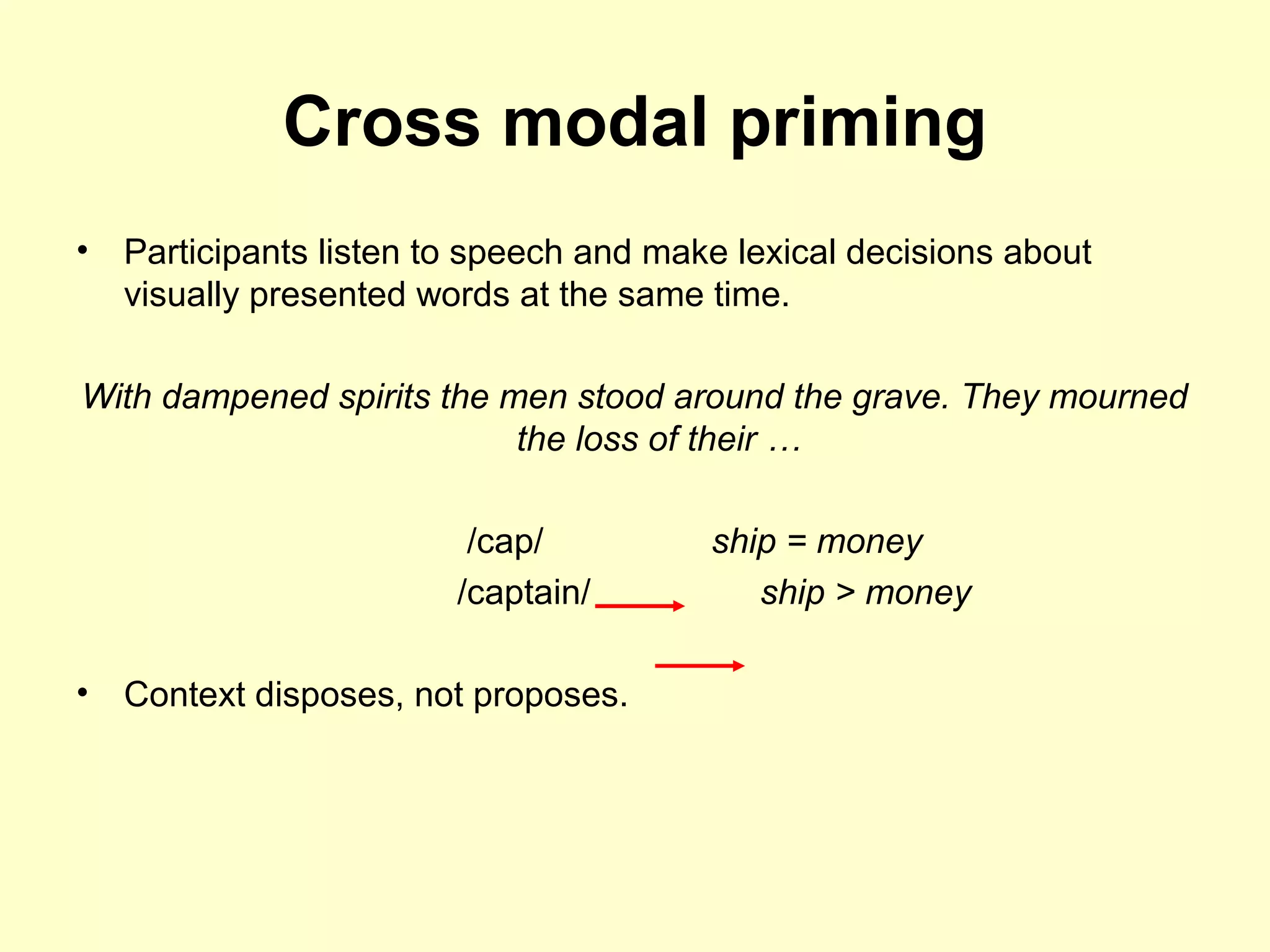

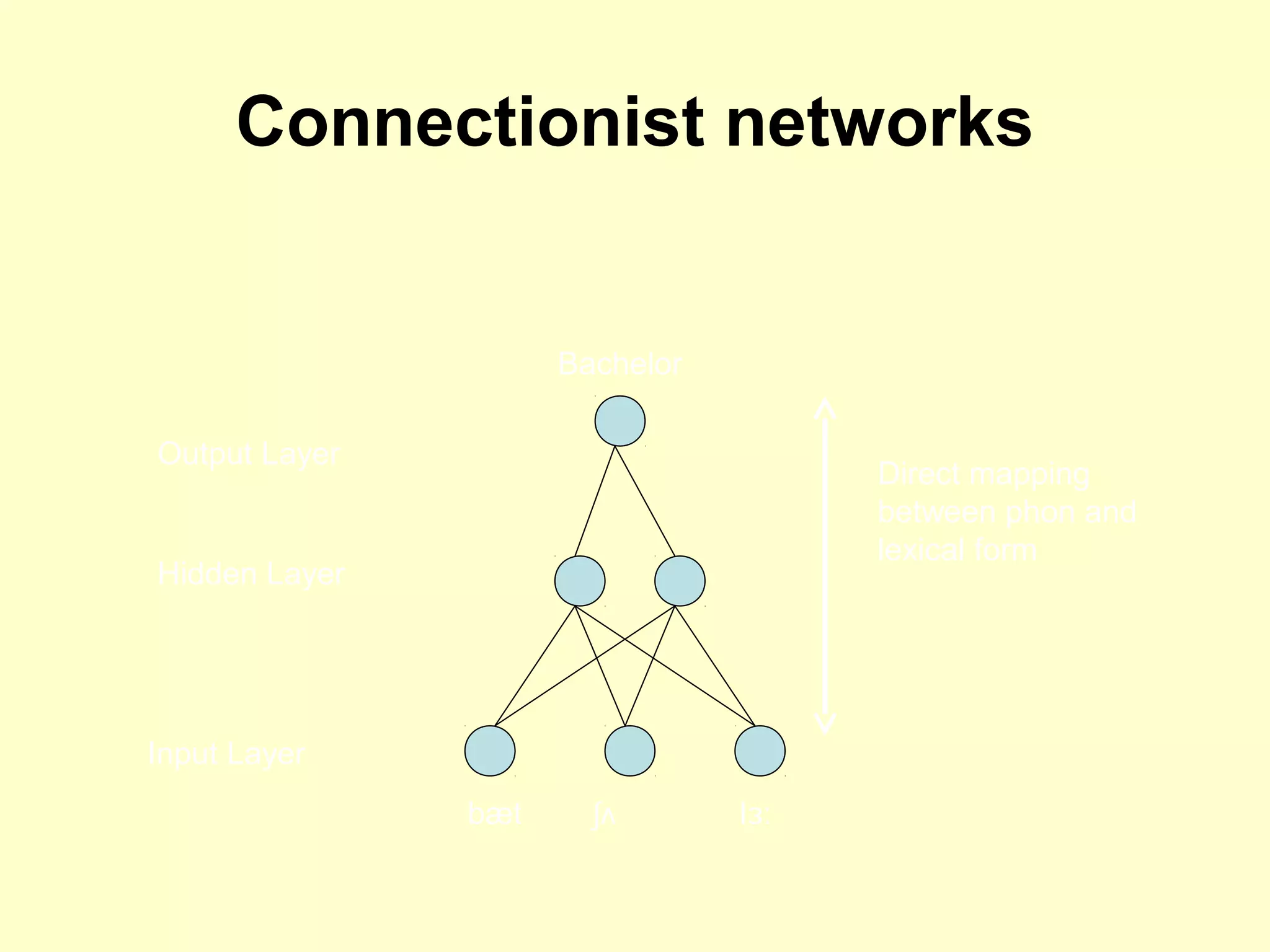

This document discusses approaches to lexical semantic representation and lexical access. It covers semantic networks, prototype theory, exemplar theory, and theory-based approaches to lexical semantic representation. It also discusses the cohort model of lexical access and how connectionist models provide an explicit account of the processes involved in lexical access. The key points are that lexical access is primarily bottom-up, driven by partial perceptual information, and that both similarity-based and relational approaches as well as deeper theory-driven knowledge influence lexical semantic representation.