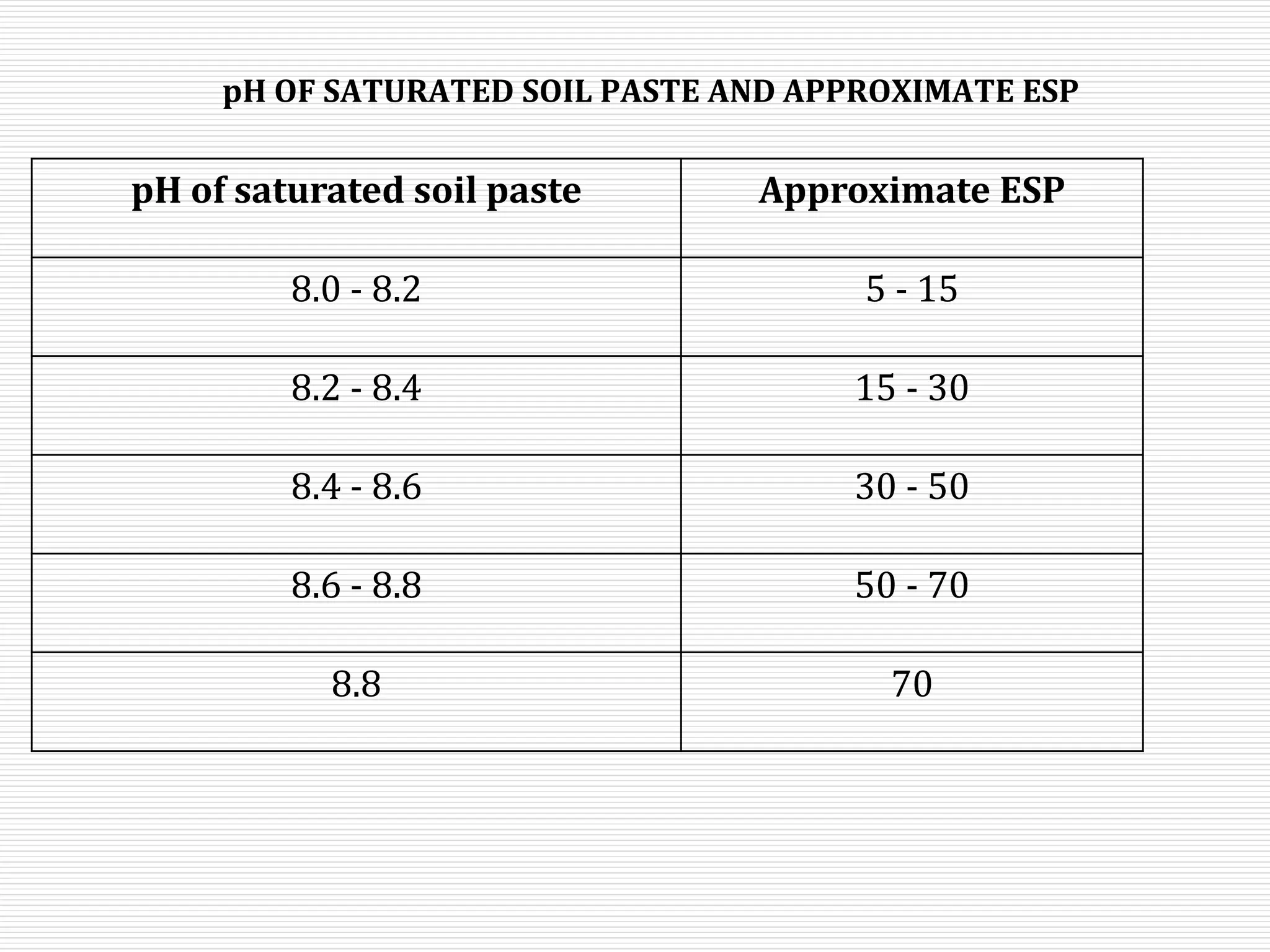

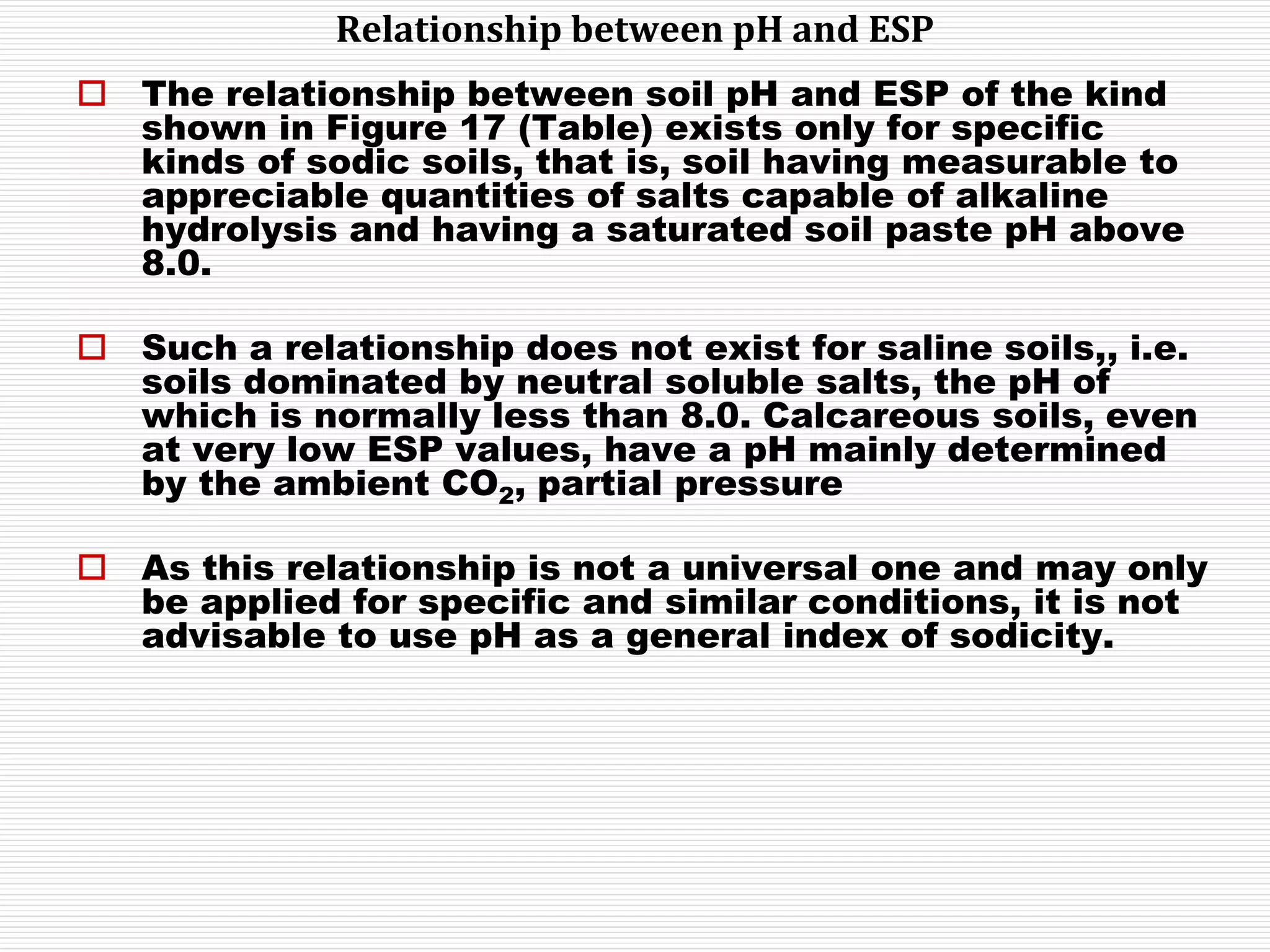

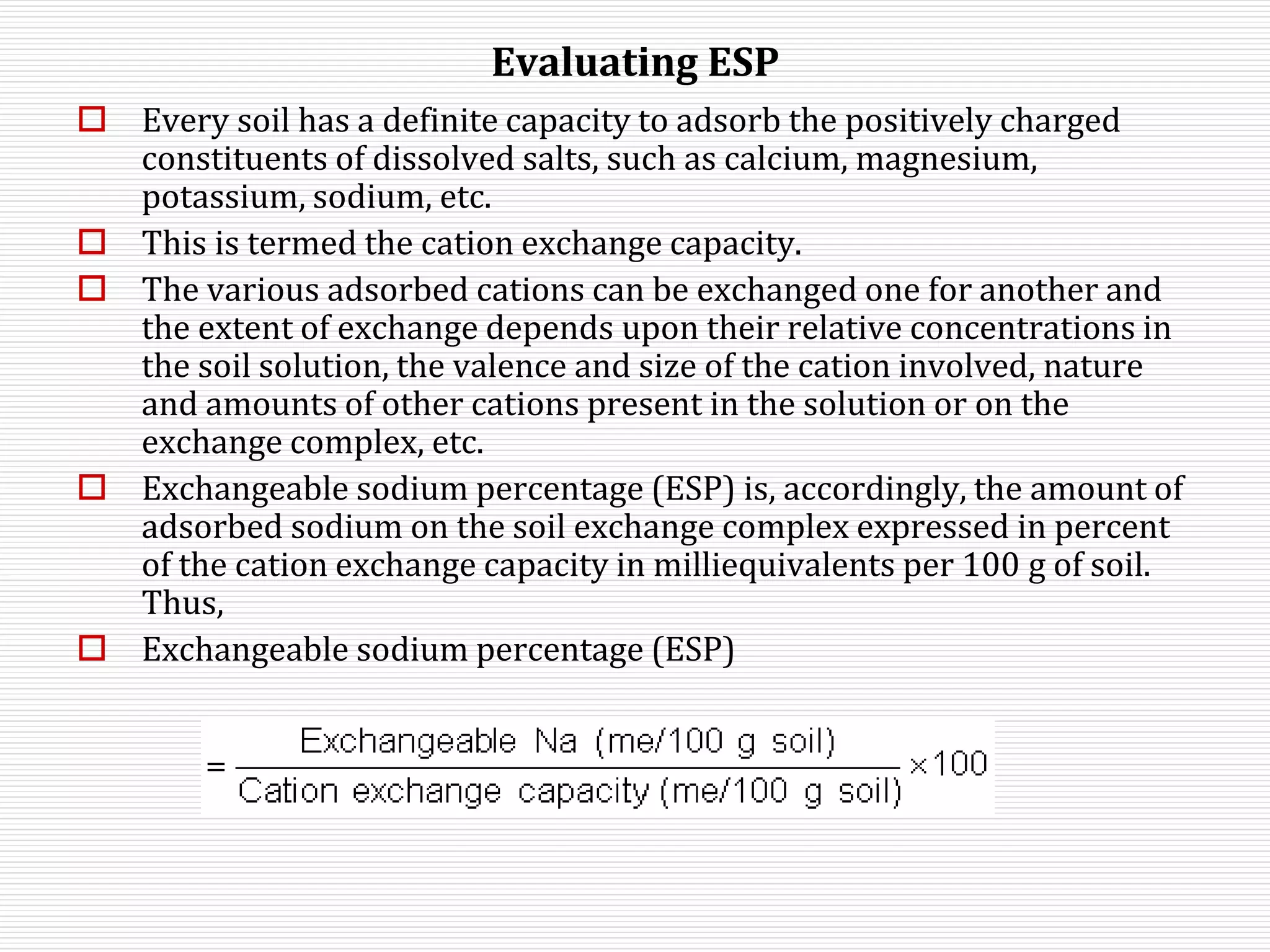

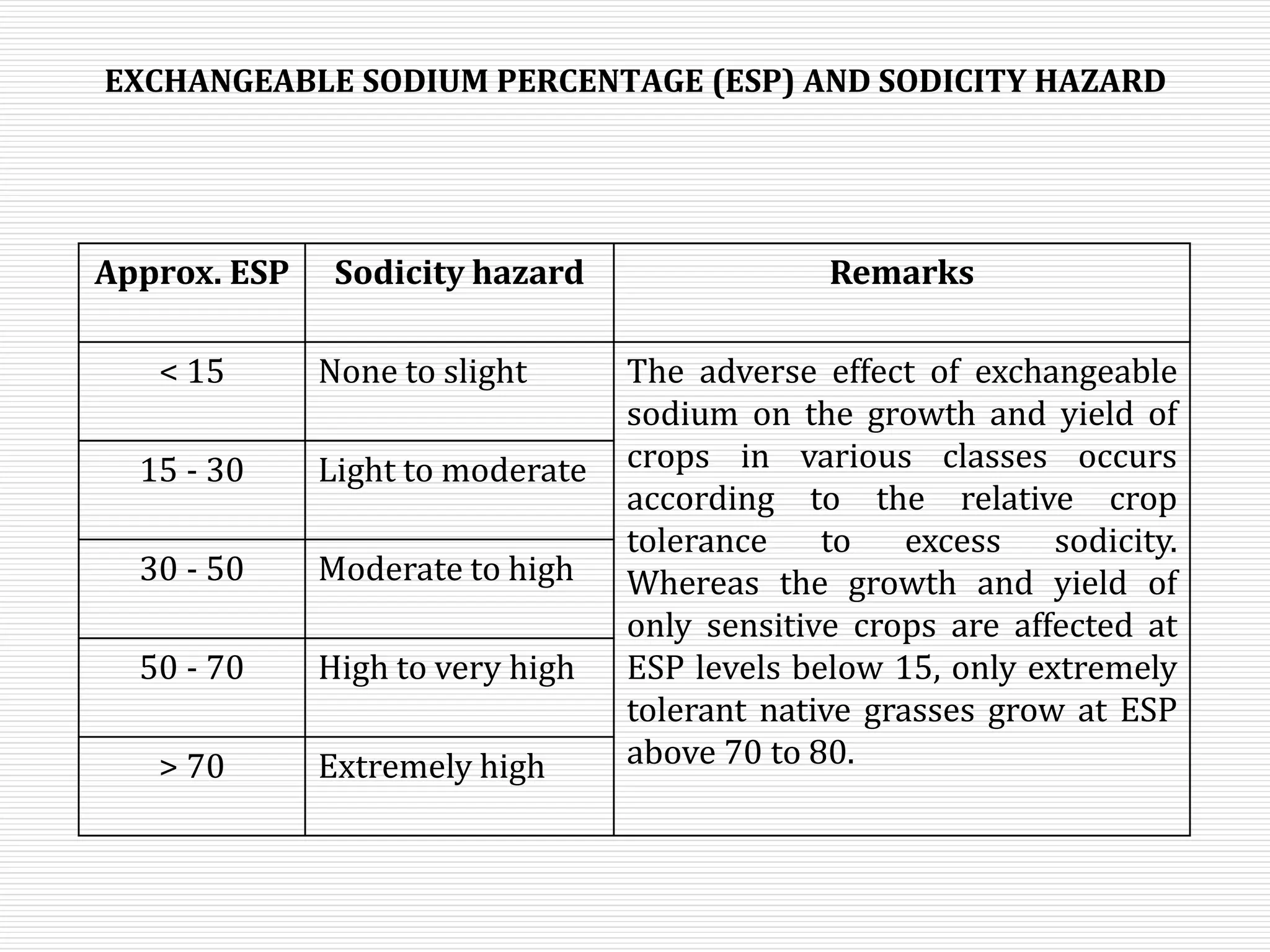

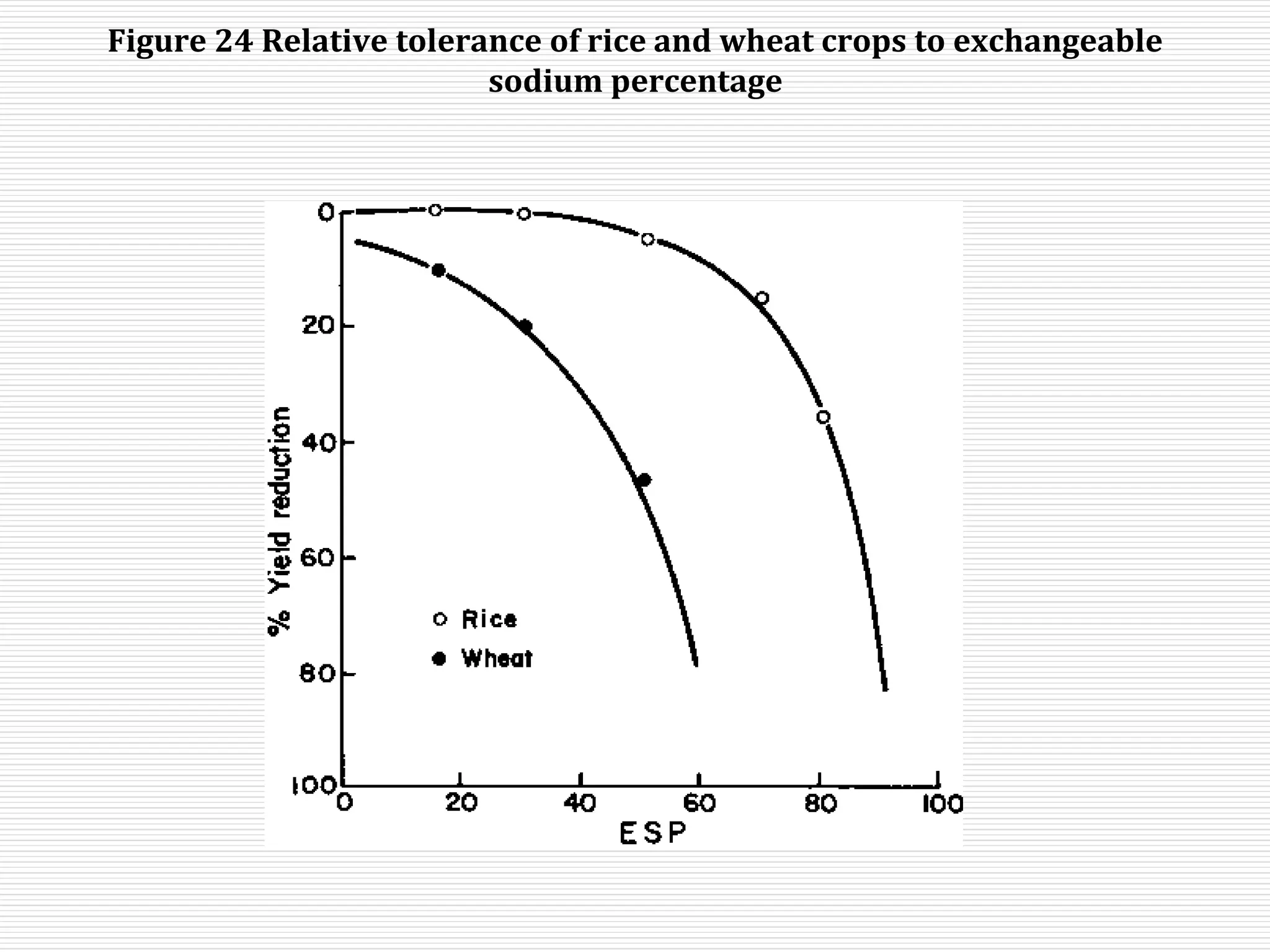

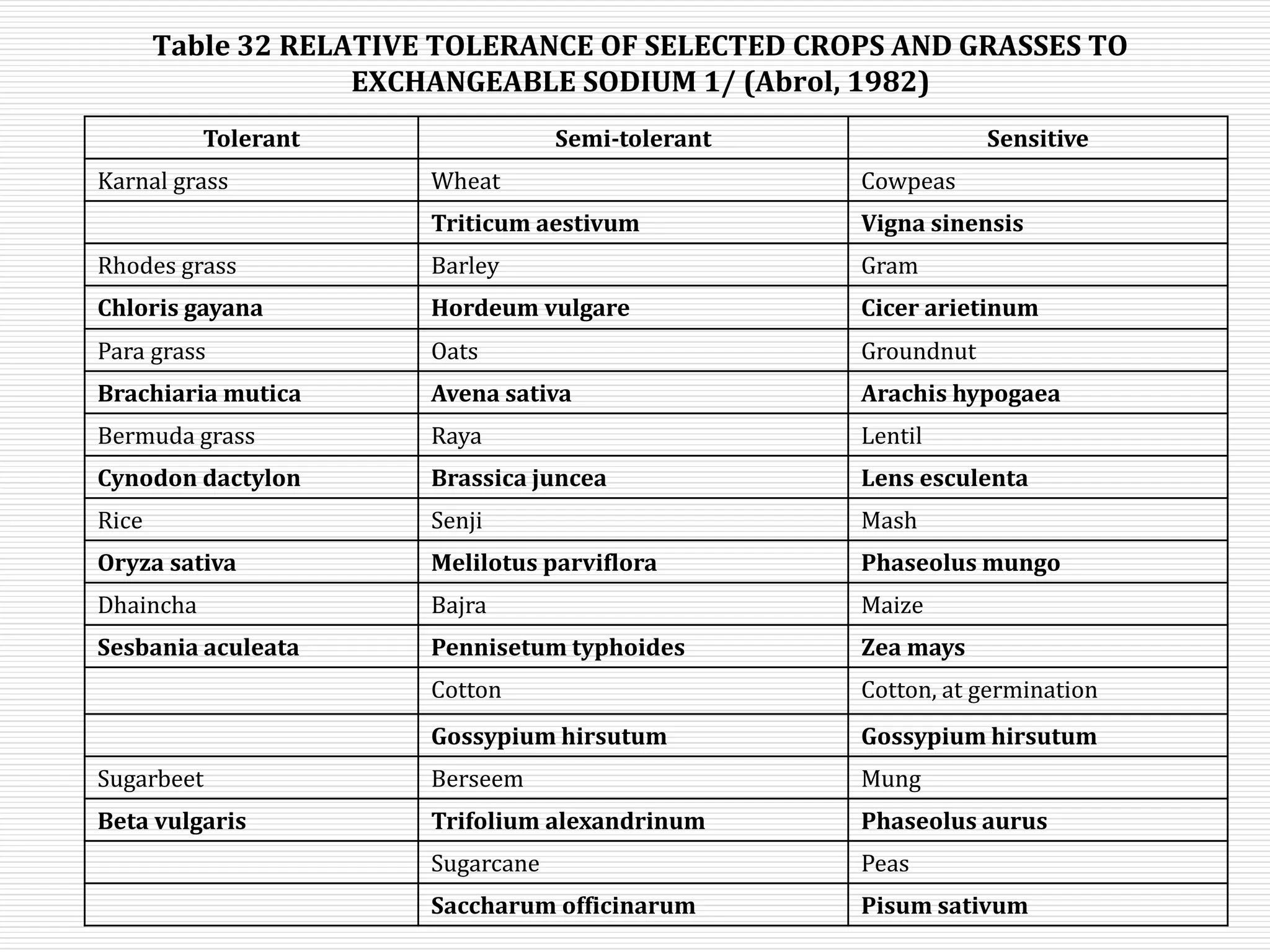

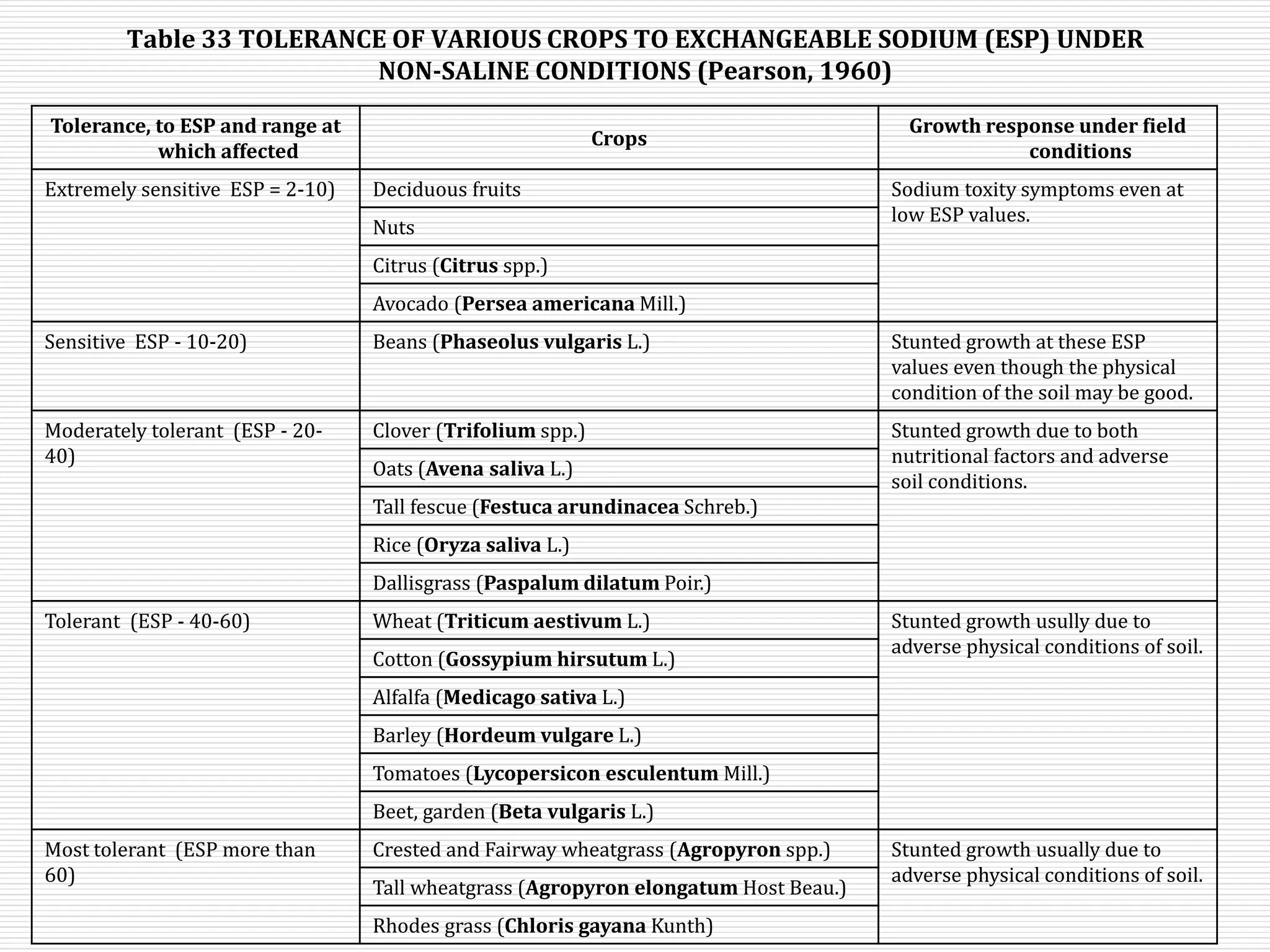

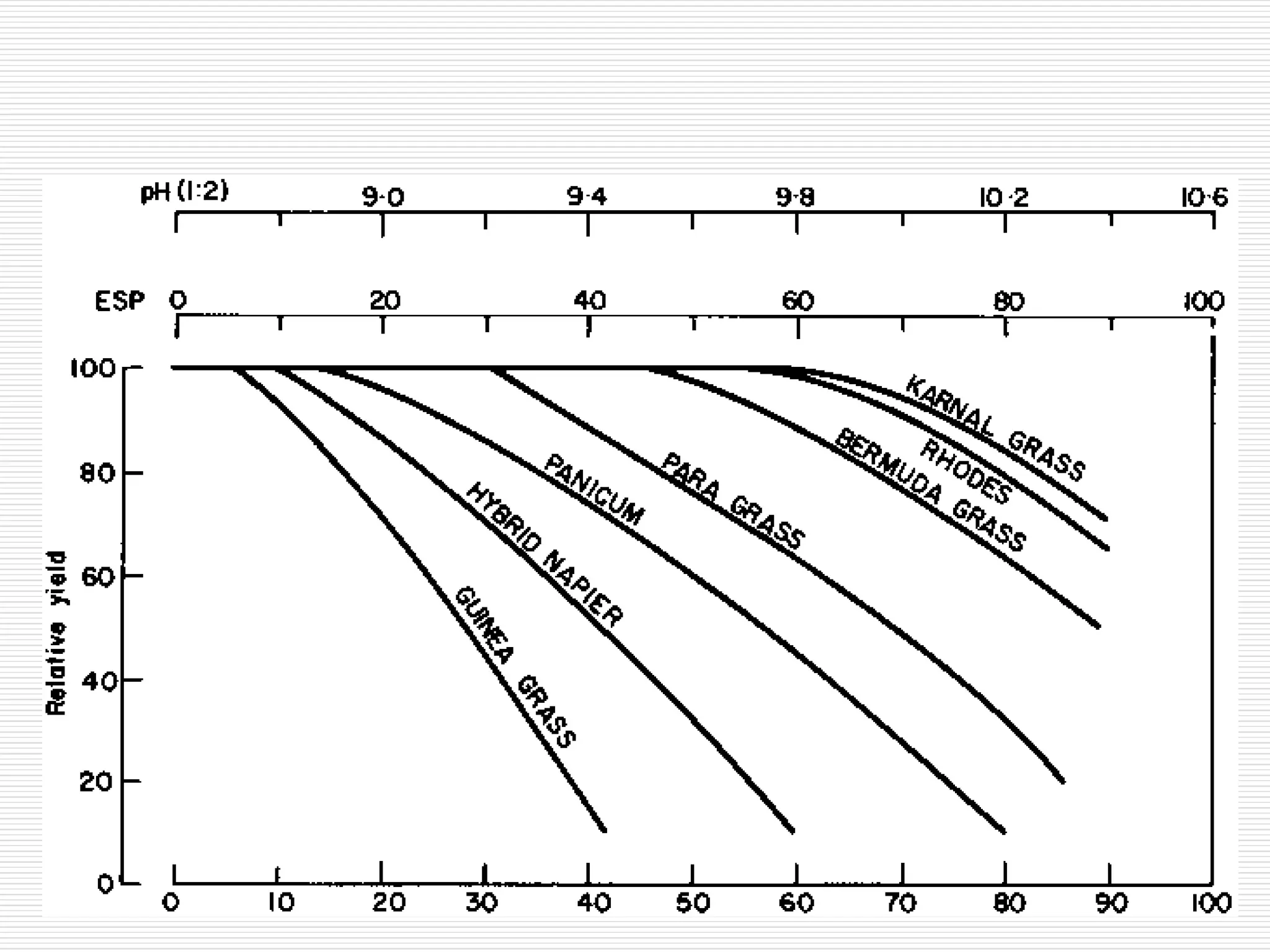

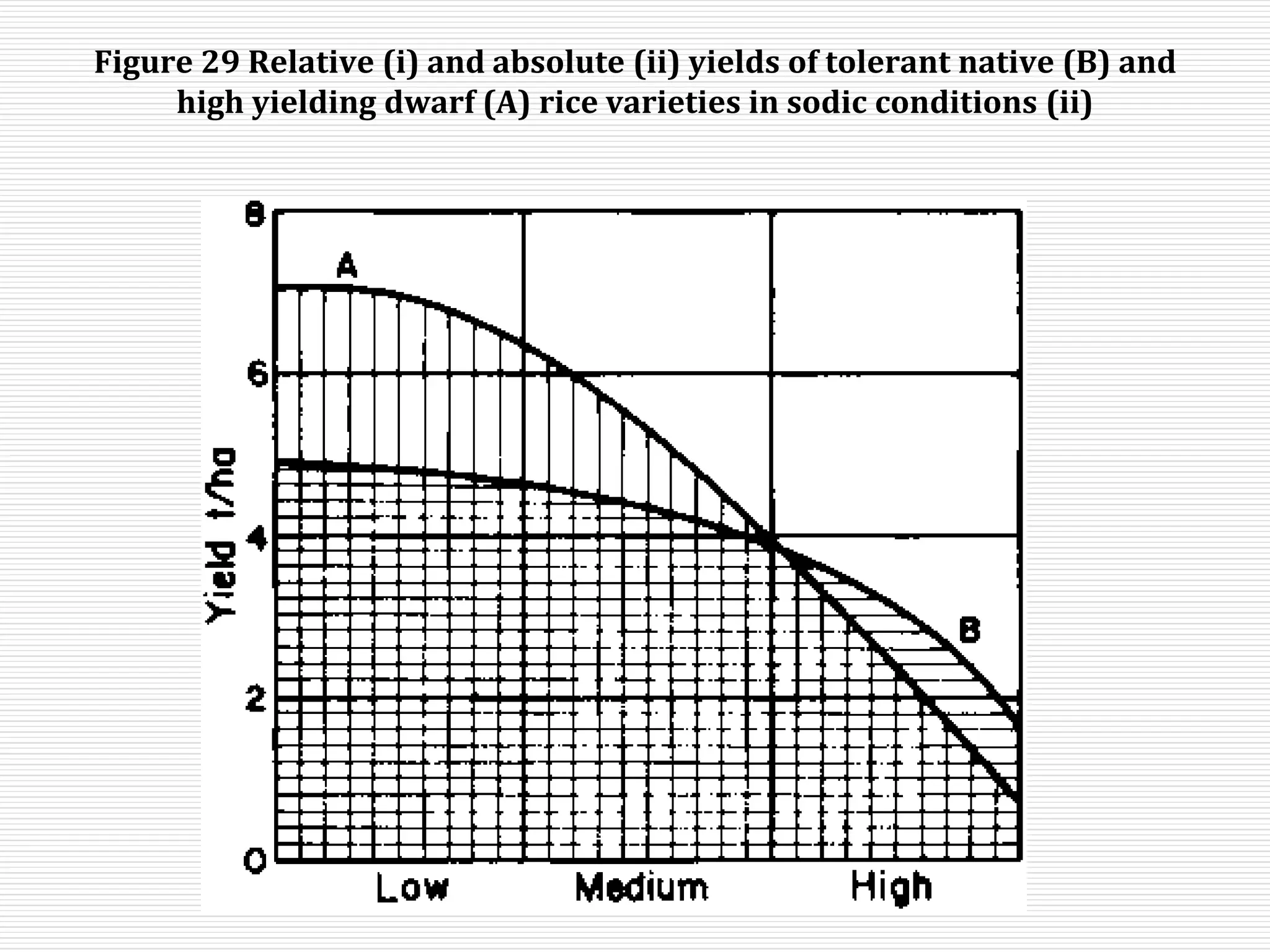

This document discusses sodic soils, including their mode of formation, characteristics, and impact on plant growth. Sodic soils form through processes like desalinization, reduction of sulfate ions, or concentration of soil solutions during wet and dry seasons. They are characterized by an exchangeable sodium percentage (ESP) over 15, pH over 8.2, and presence of salts that hydrolyze alkali like sodium carbonate. High exchangeable sodium negatively impacts soil structure and nutrient availability, inhibiting plant growth. The sodium adsorption ratio (SAR) of soil extracts can estimate ESP. ESP levels over 15 represent an increasing sodicity hazard for crops.