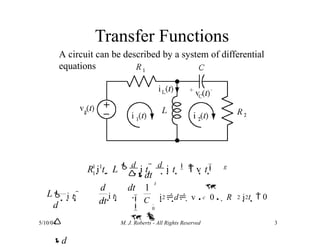

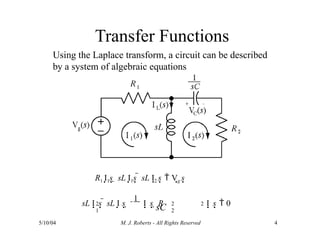

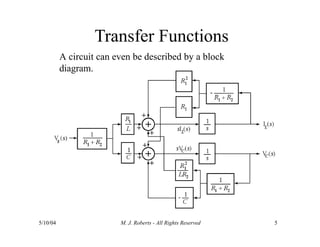

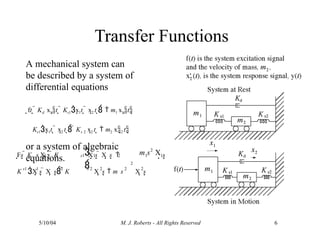

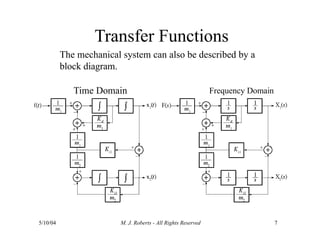

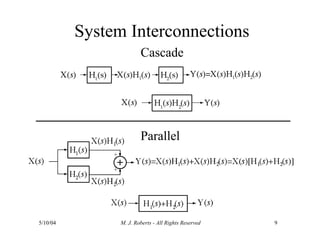

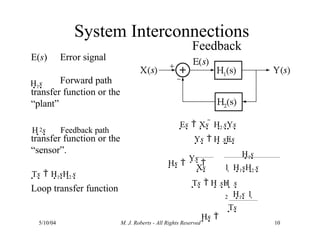

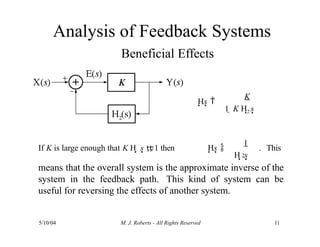

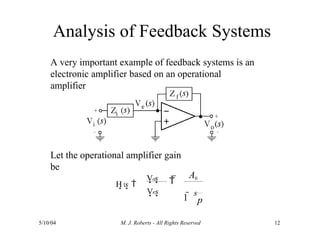

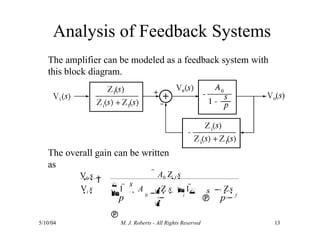

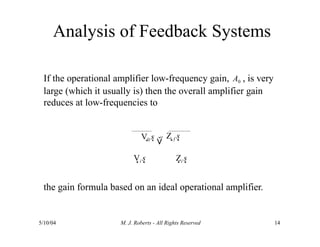

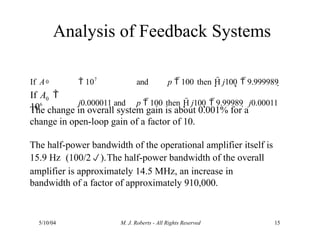

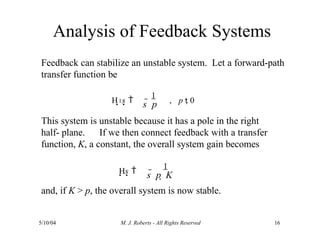

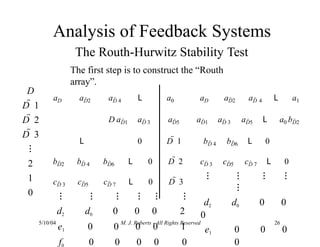

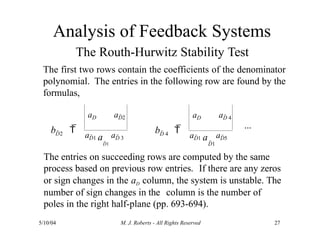

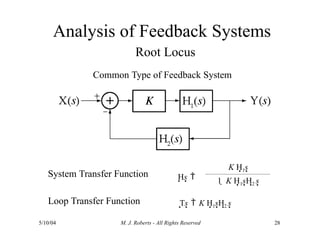

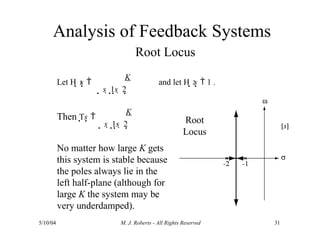

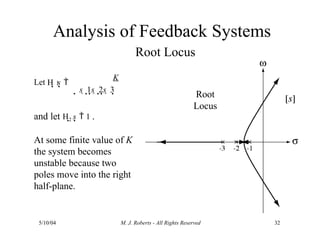

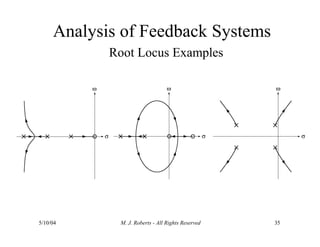

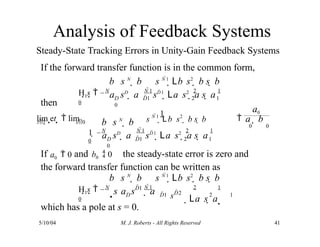

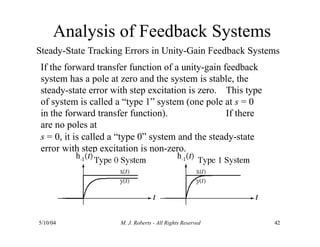

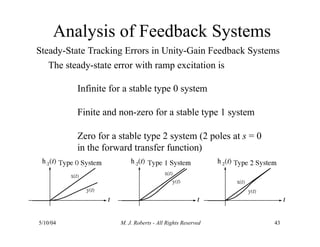

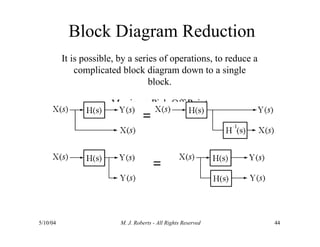

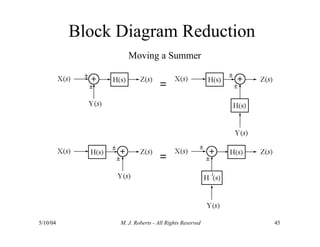

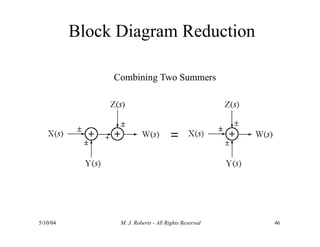

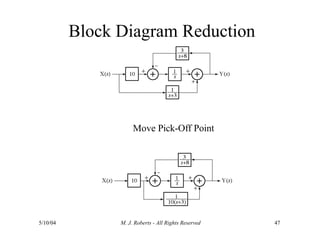

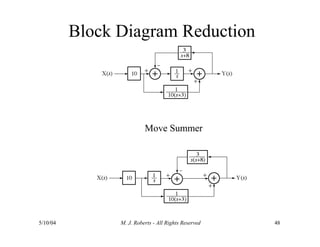

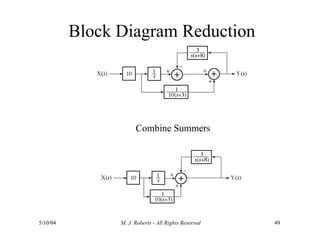

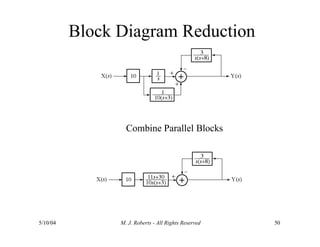

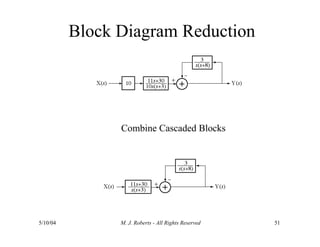

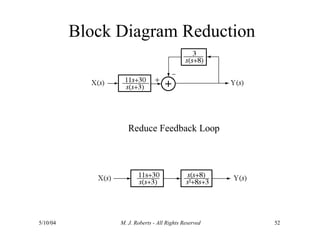

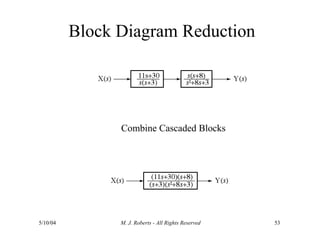

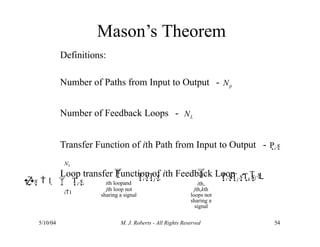

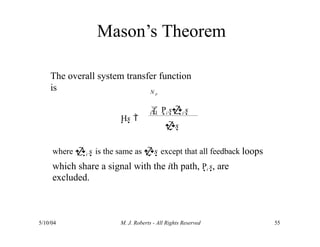

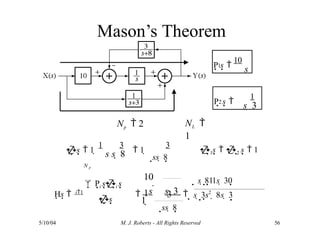

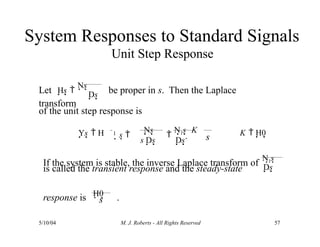

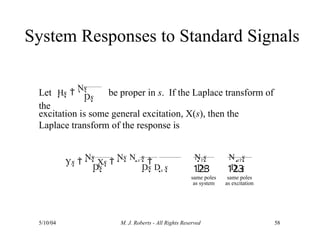

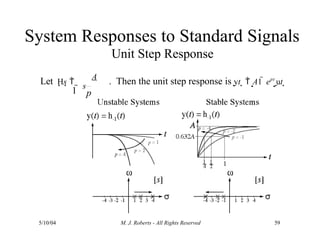

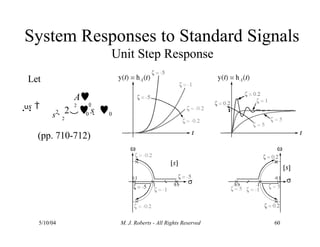

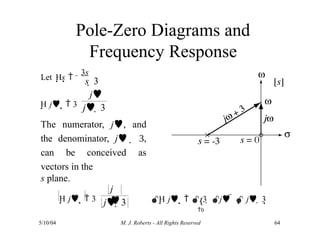

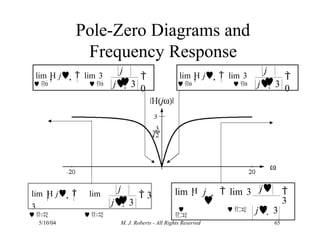

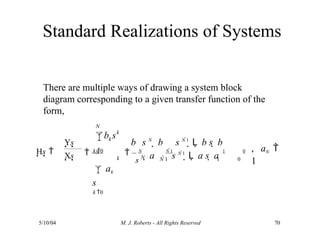

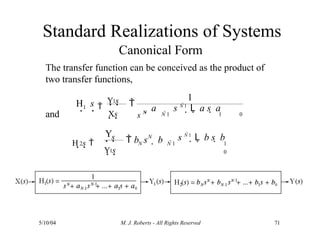

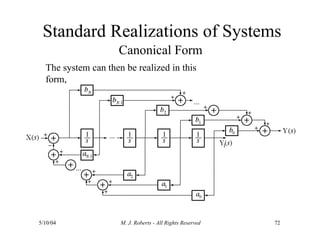

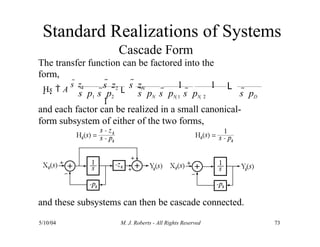

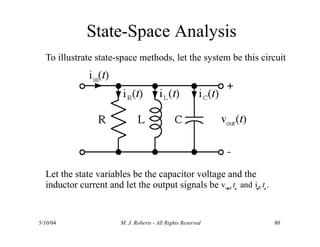

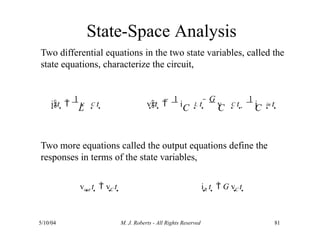

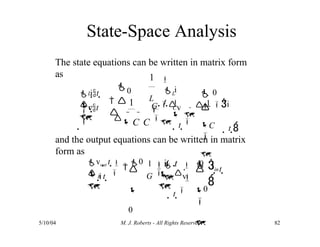

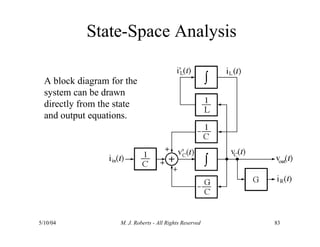

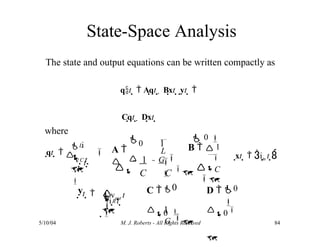

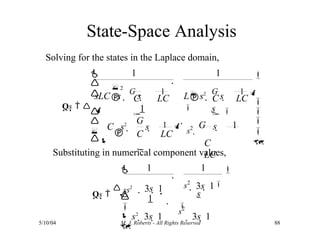

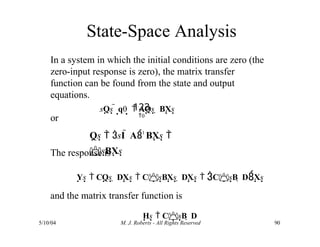

The document discusses the analysis of transfer functions for continuous-time systems using Laplace transforms, covering various methods such as differential equations, block diagrams, and circuit diagrams. It emphasizes the importance of system stability, the implications of feedback in system behavior, and the Routh-Hurwitz stability test for evaluating system stability. Additionally, it describes the concept of root locus and its role in understanding system behavior as feedback gains vary.