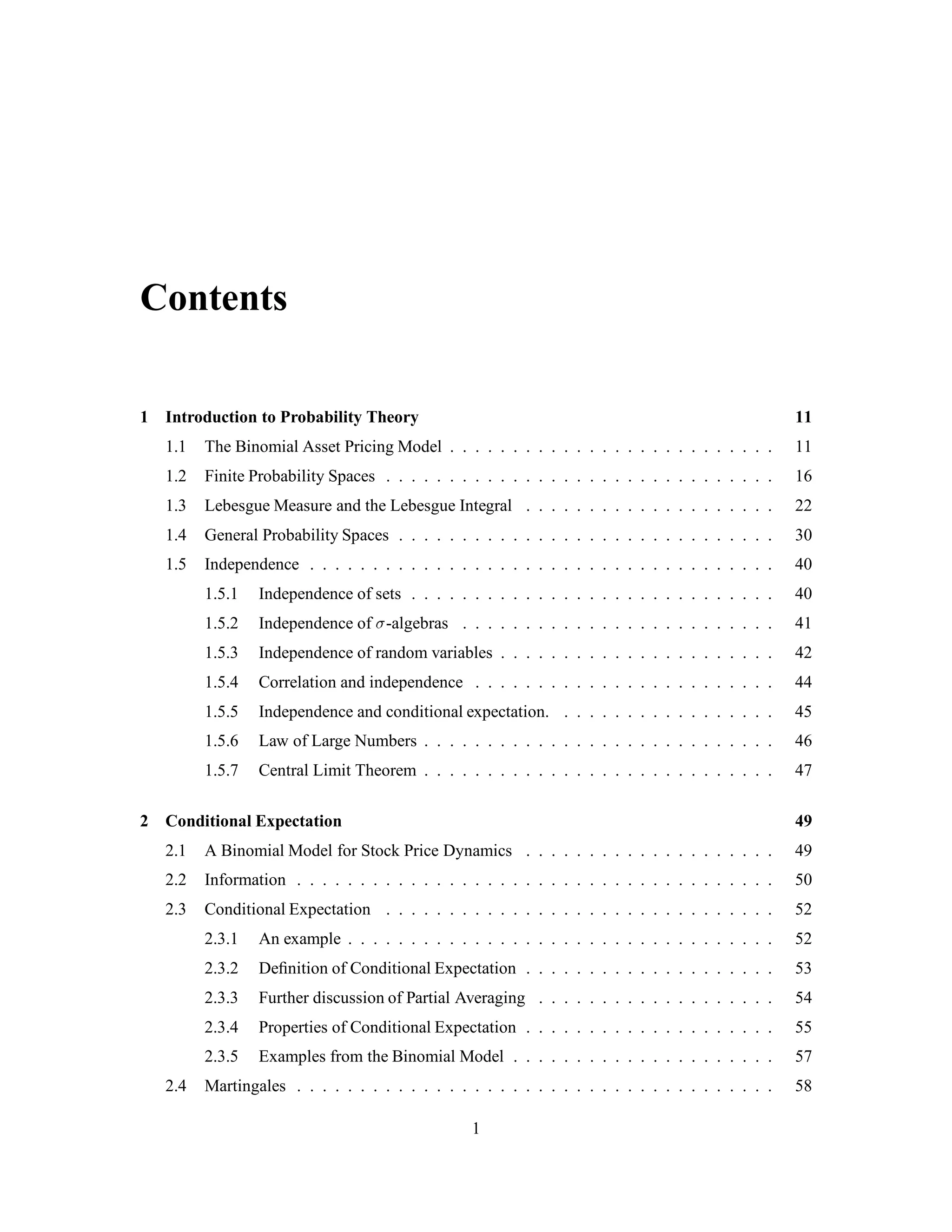

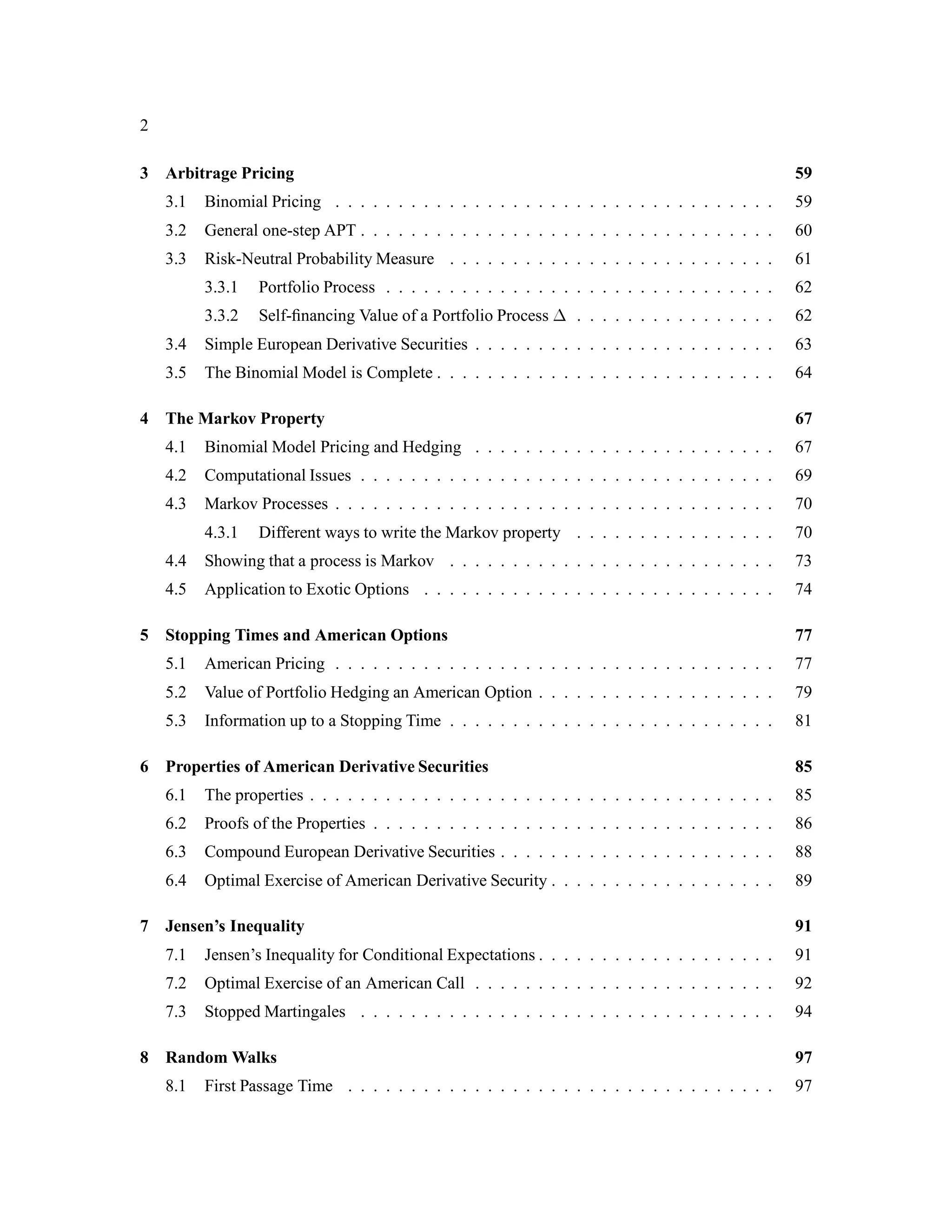

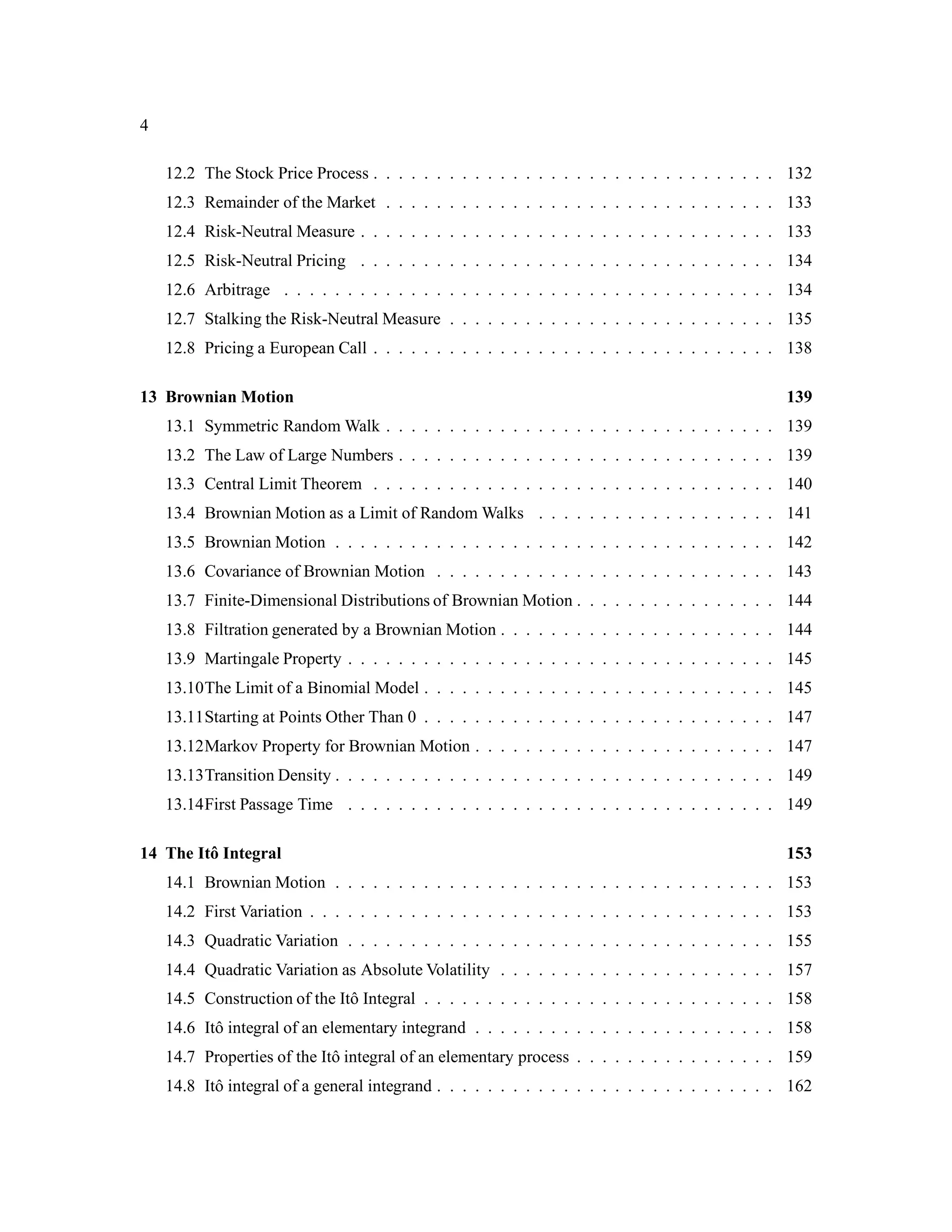

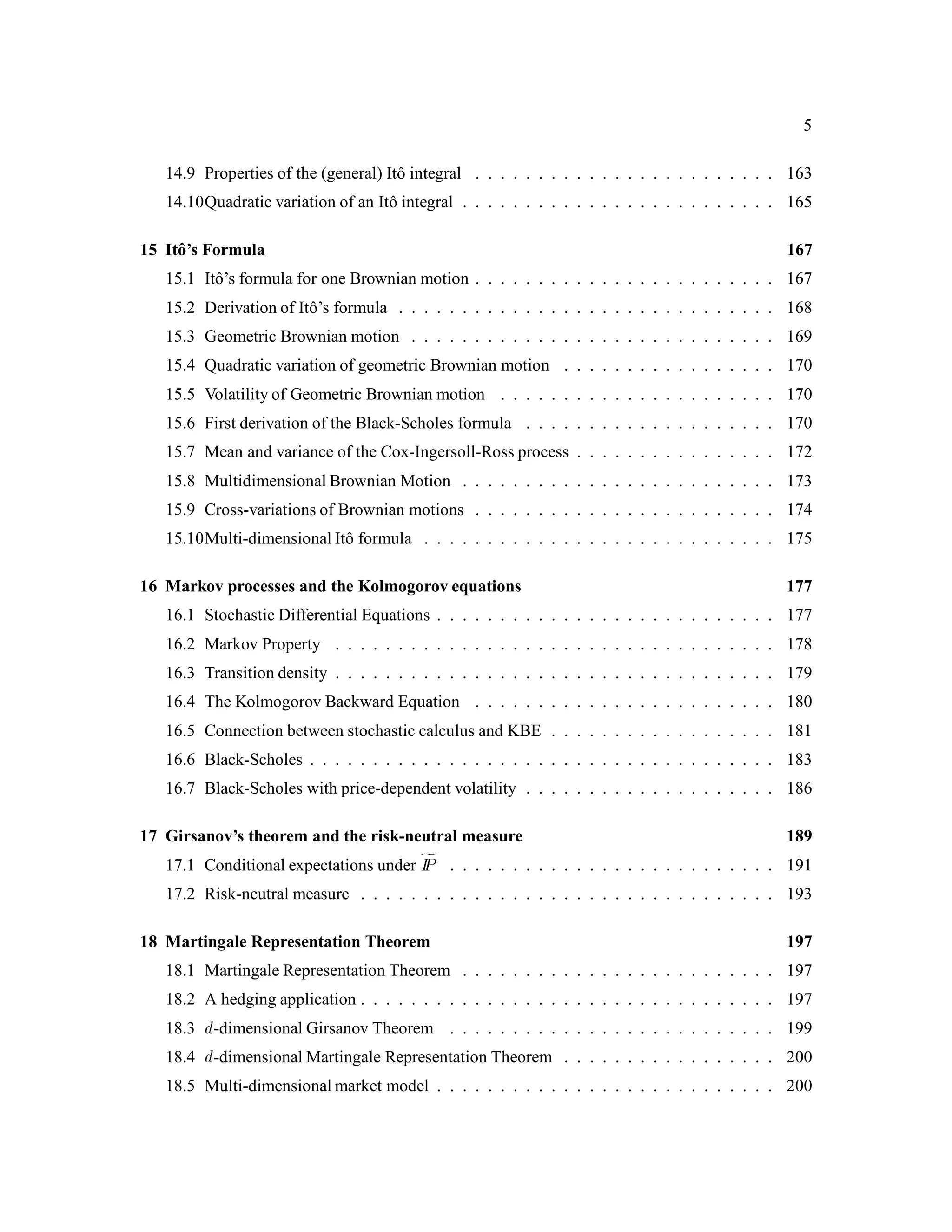

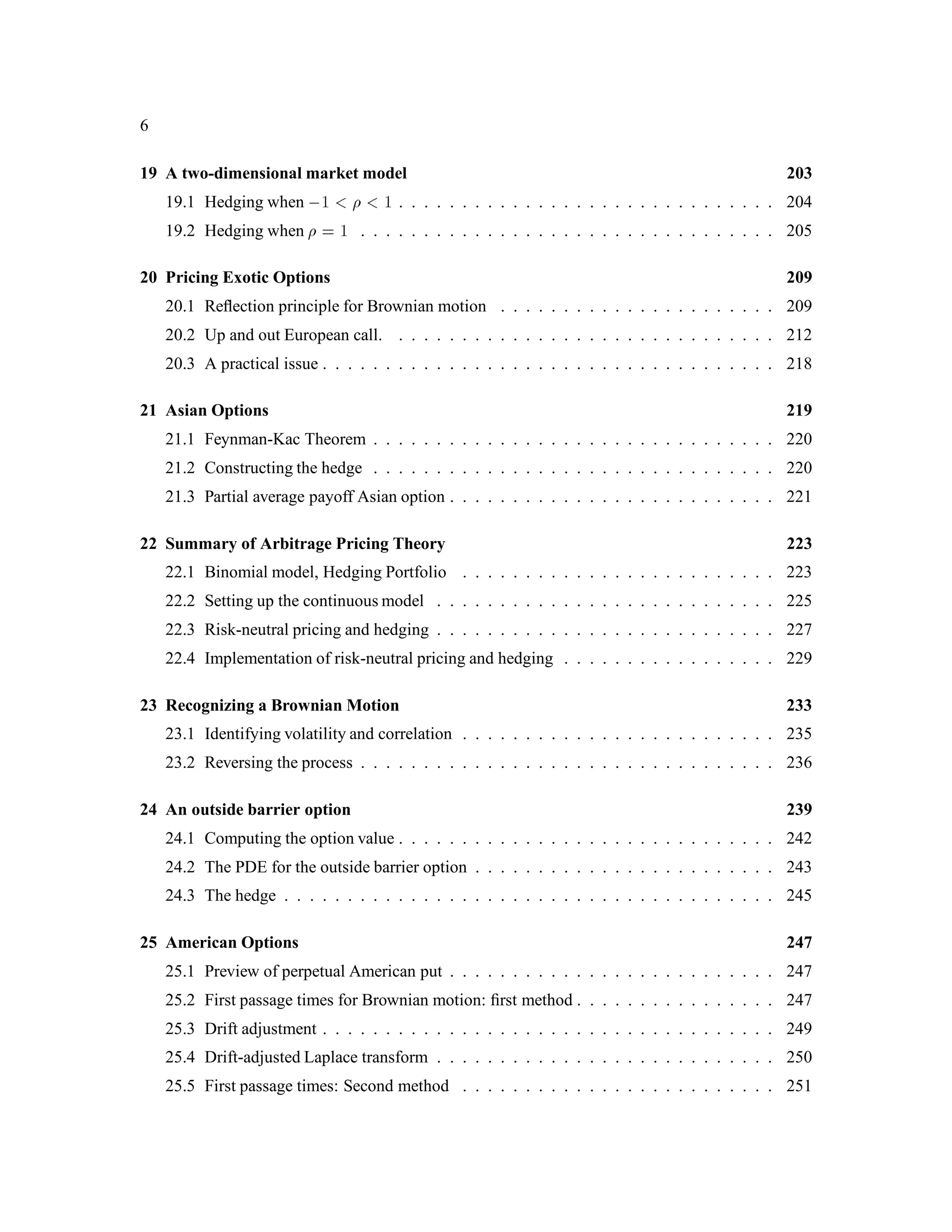

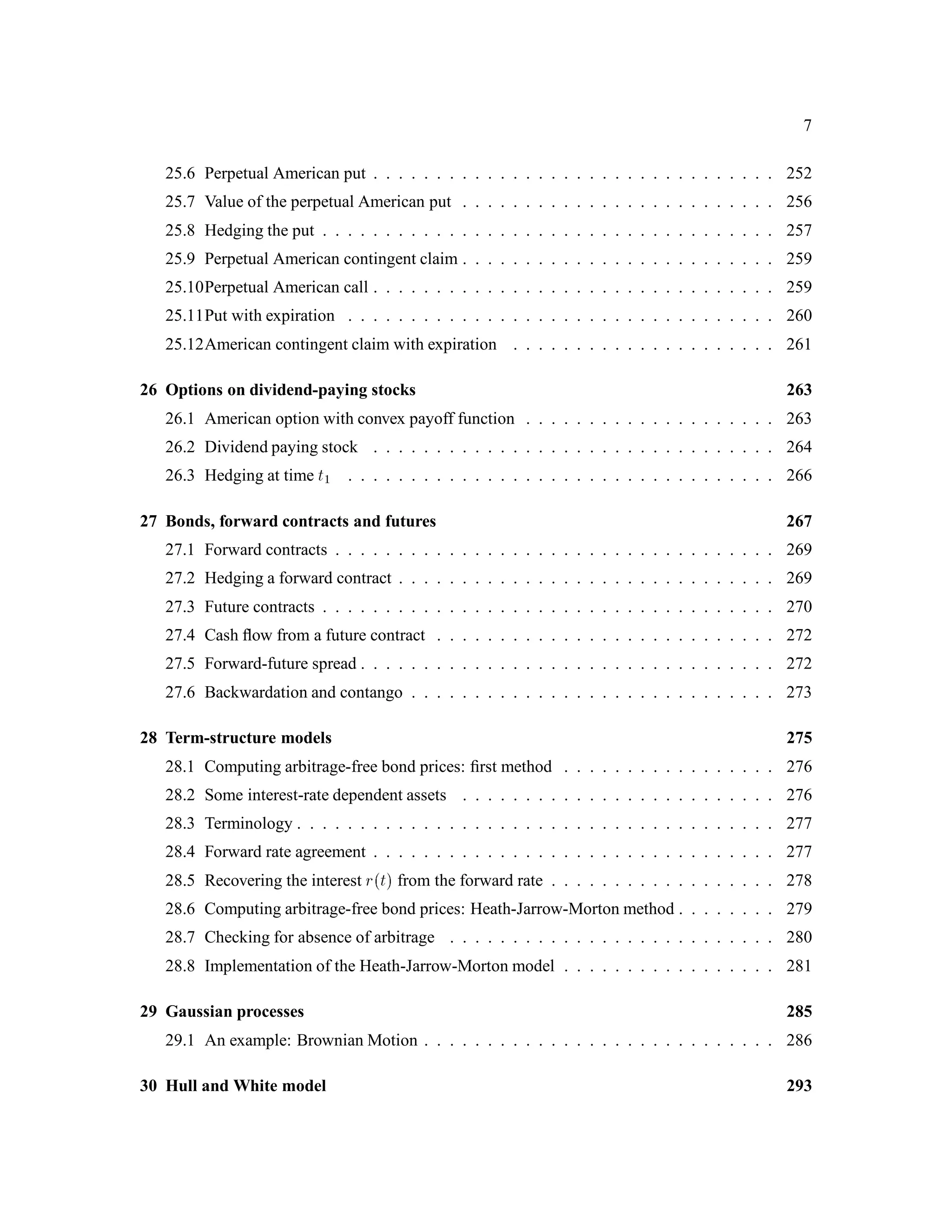

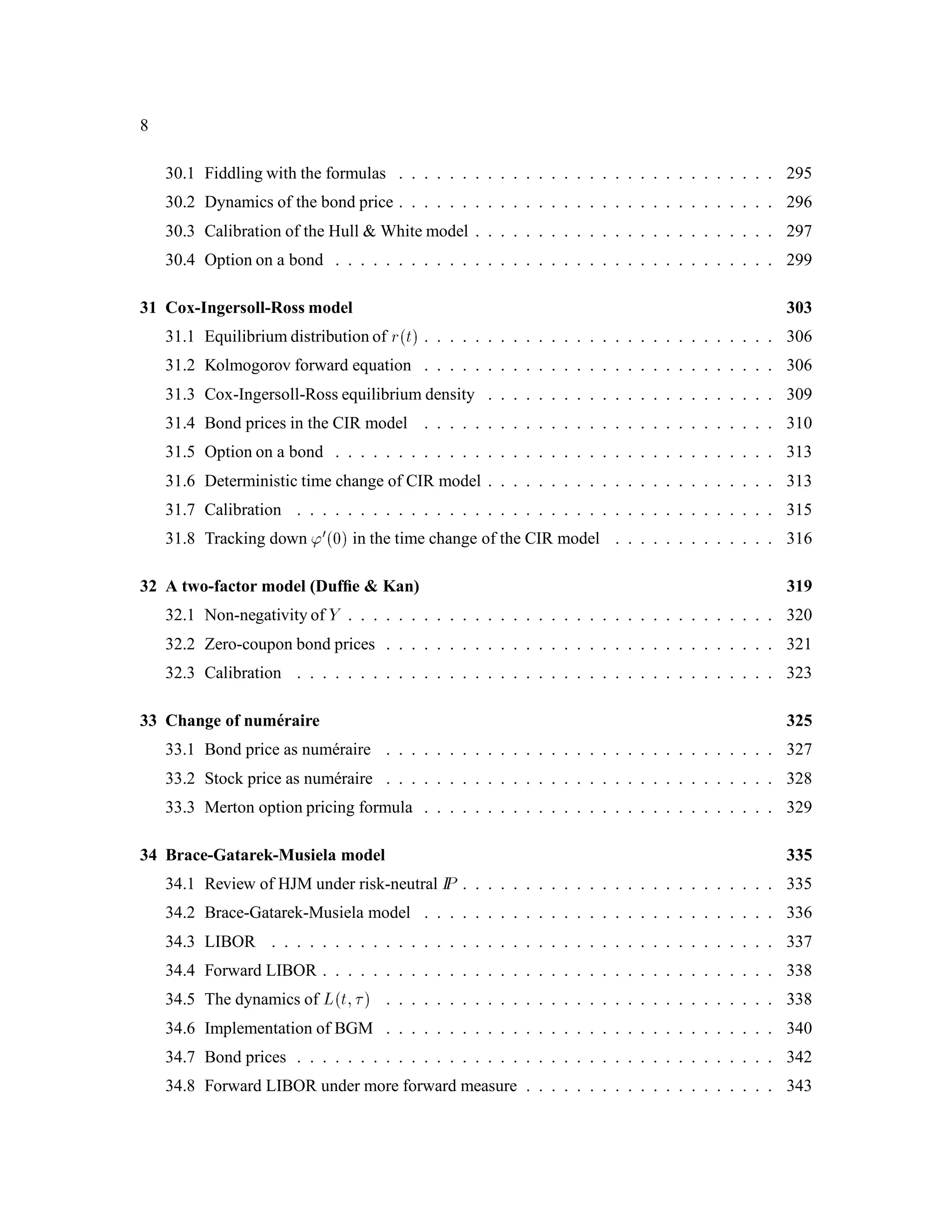

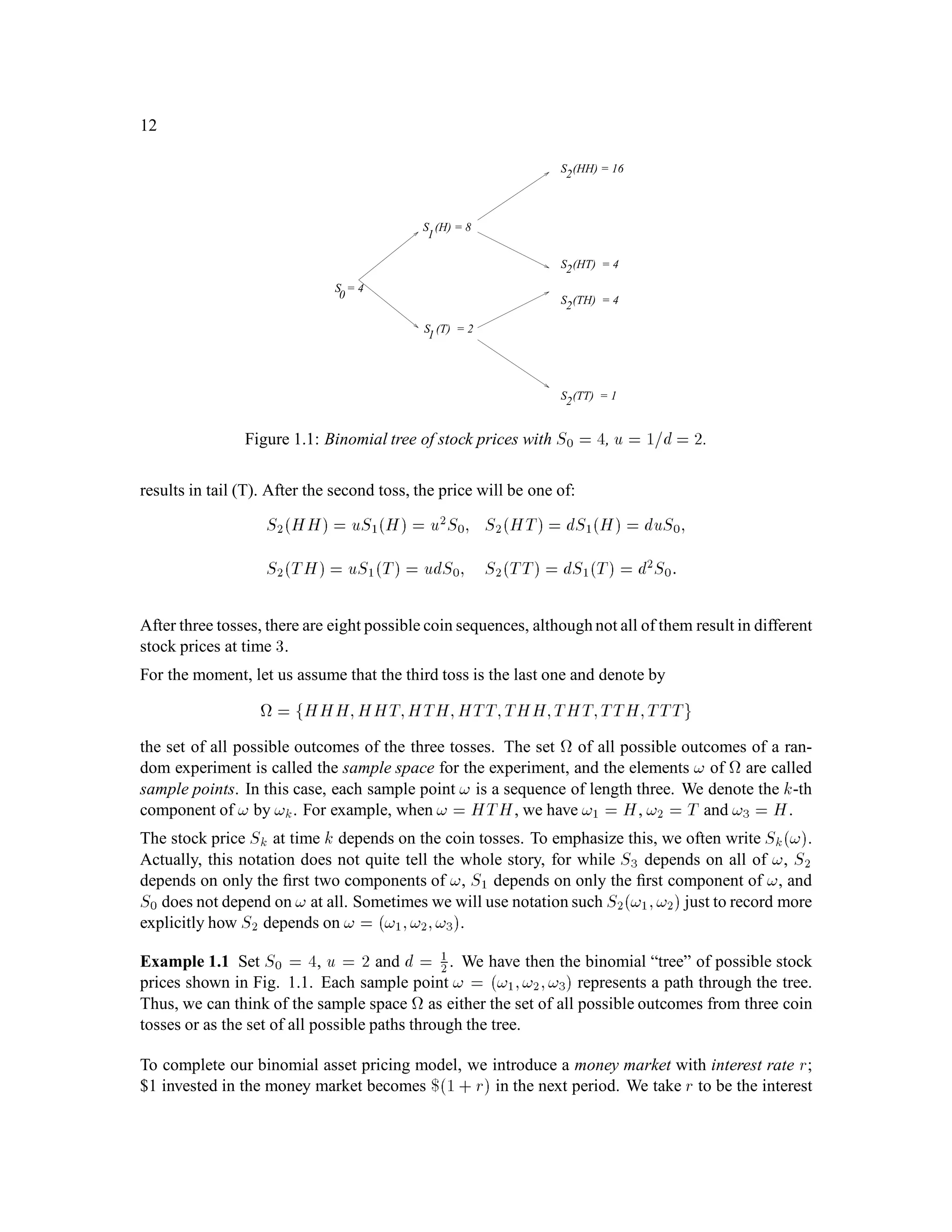

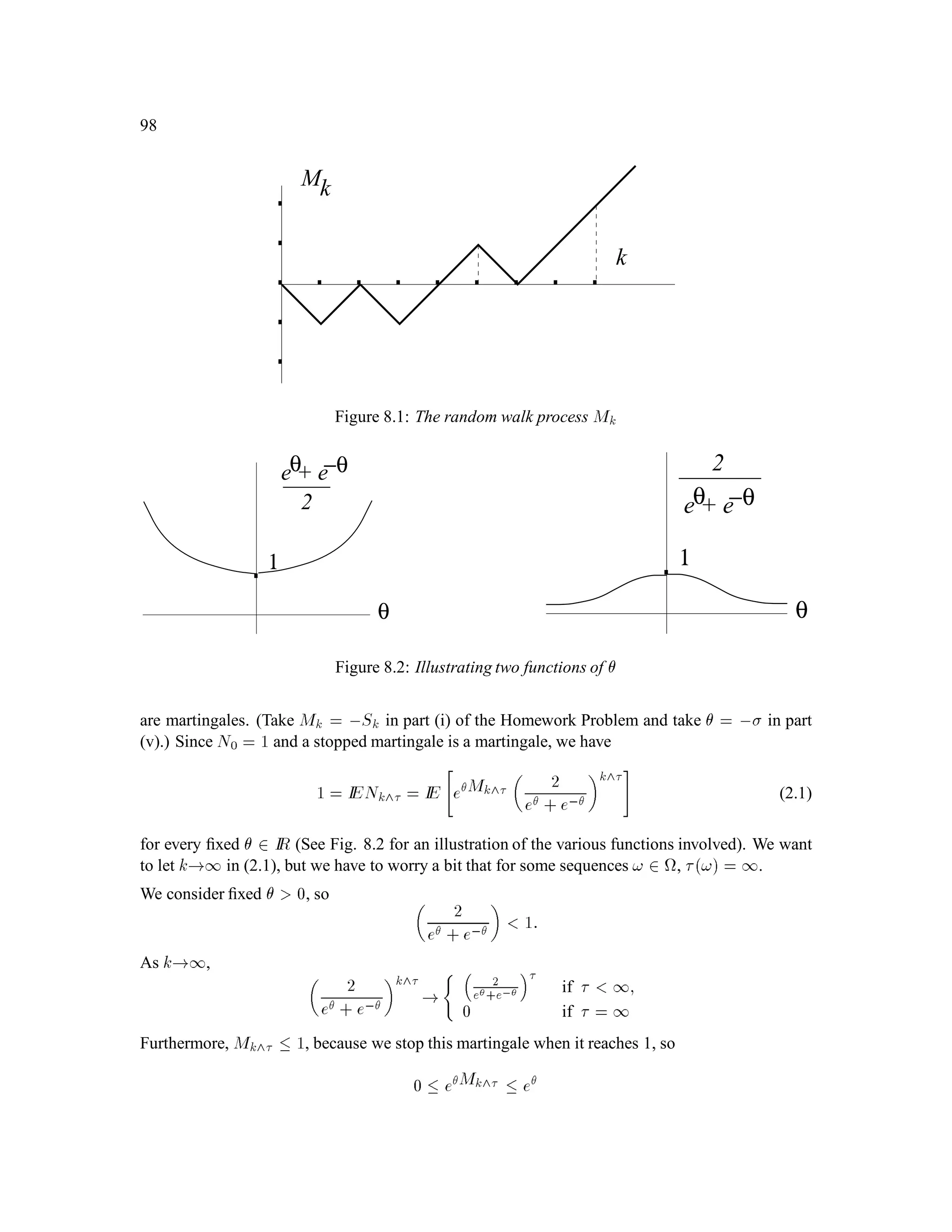

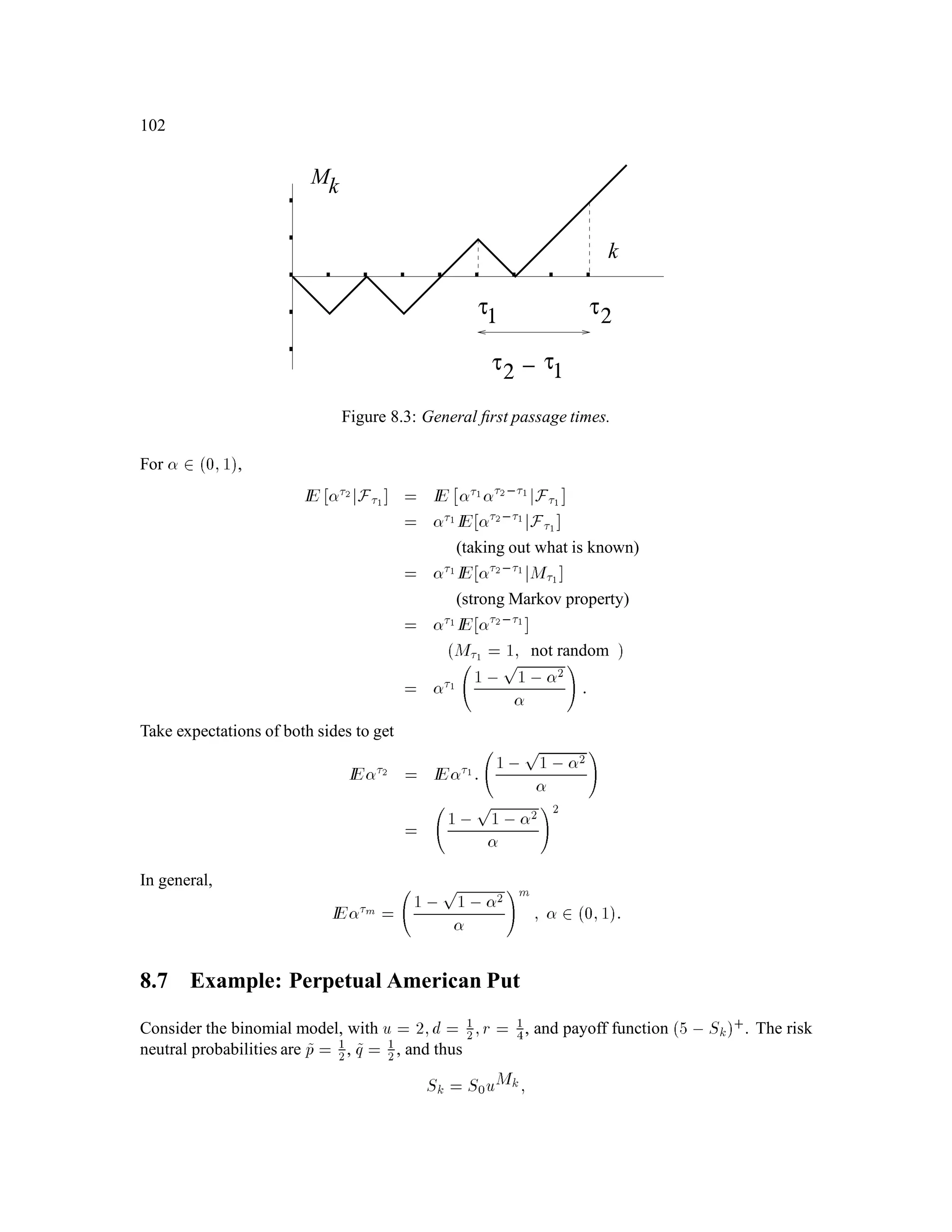

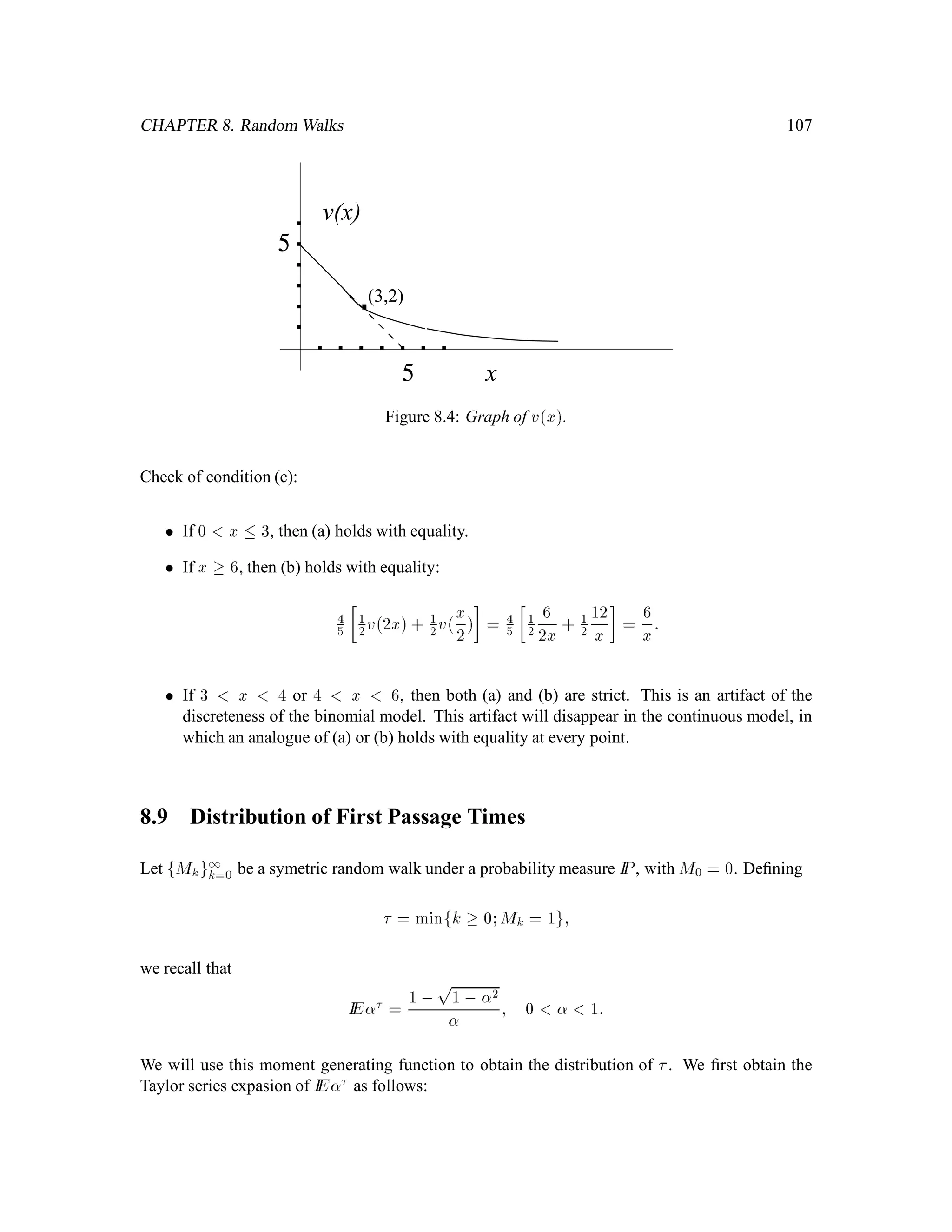

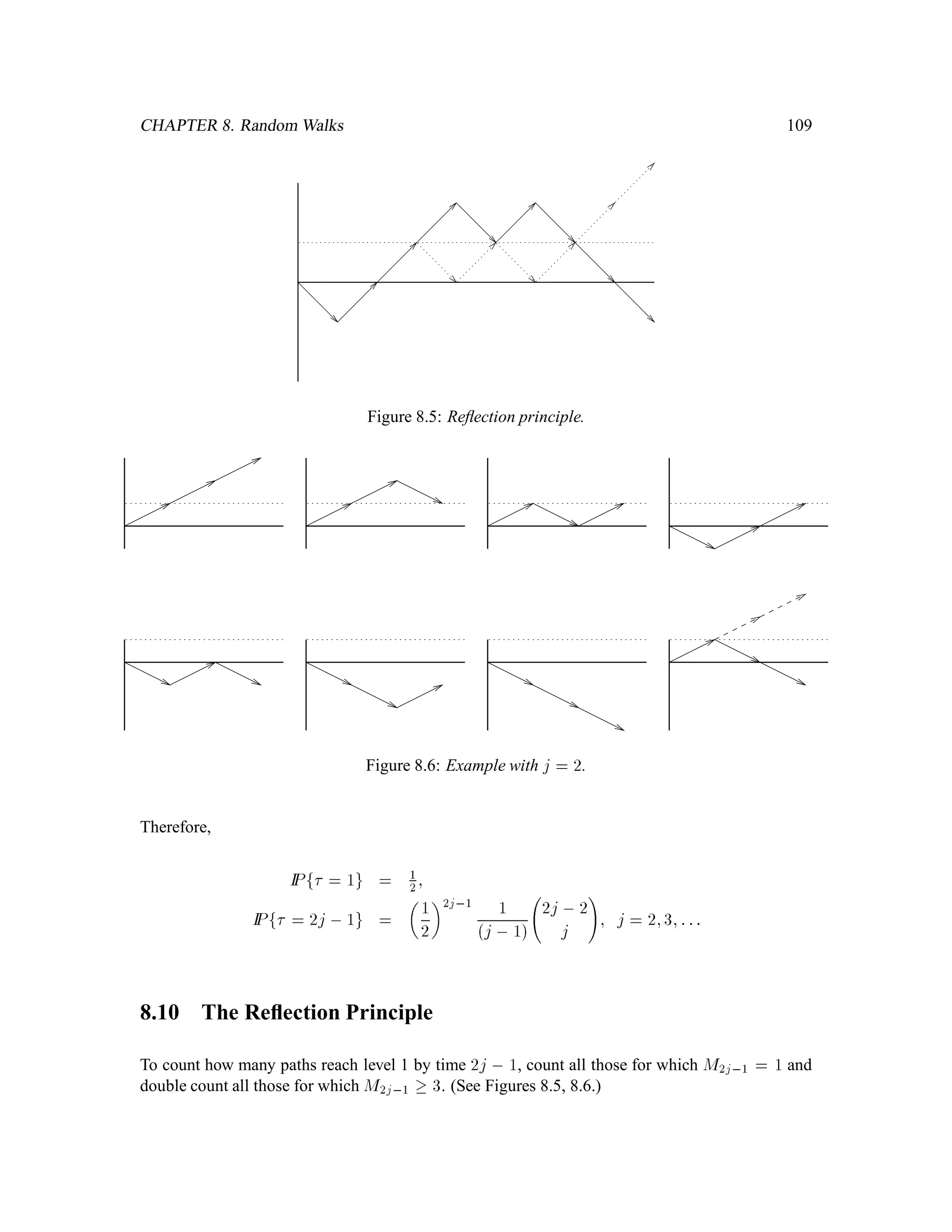

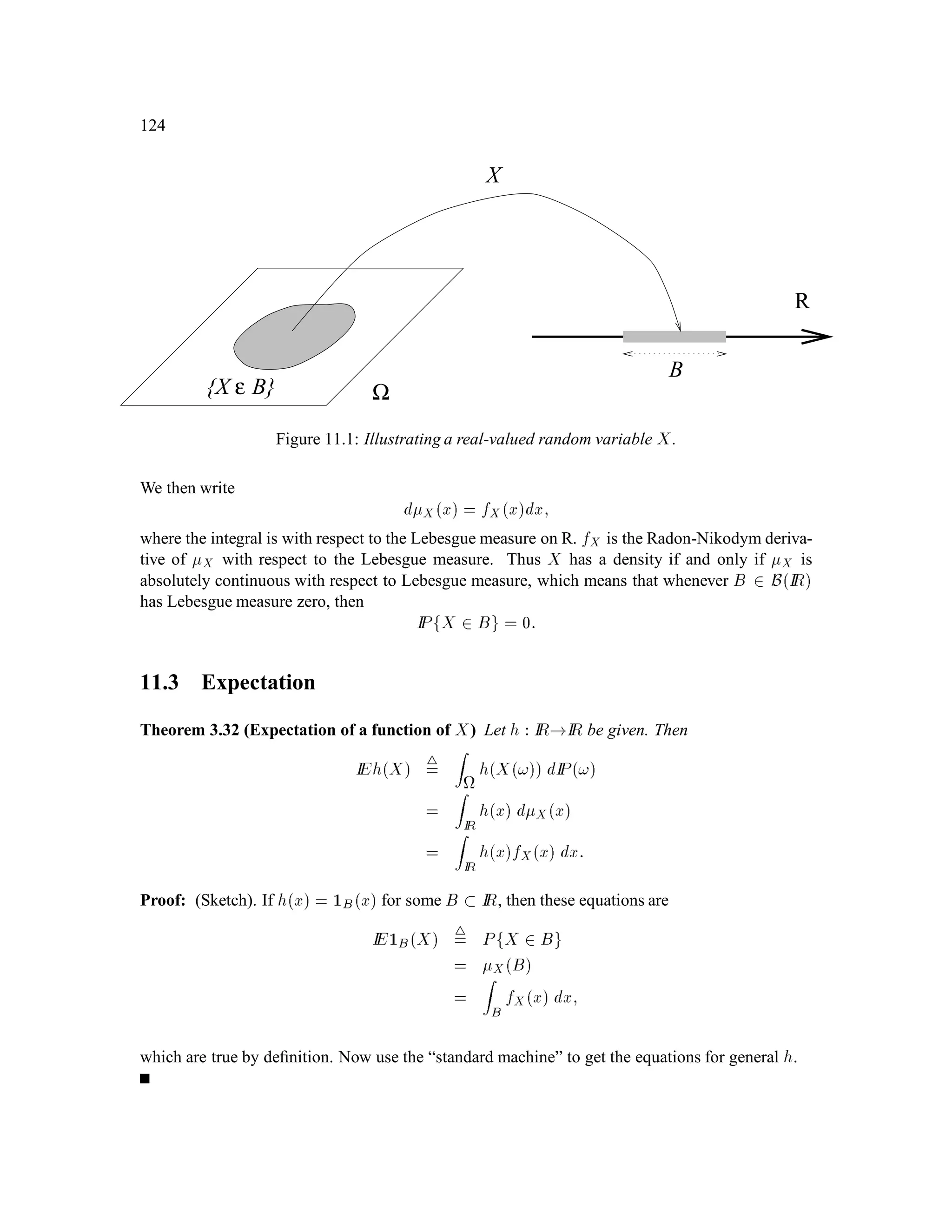

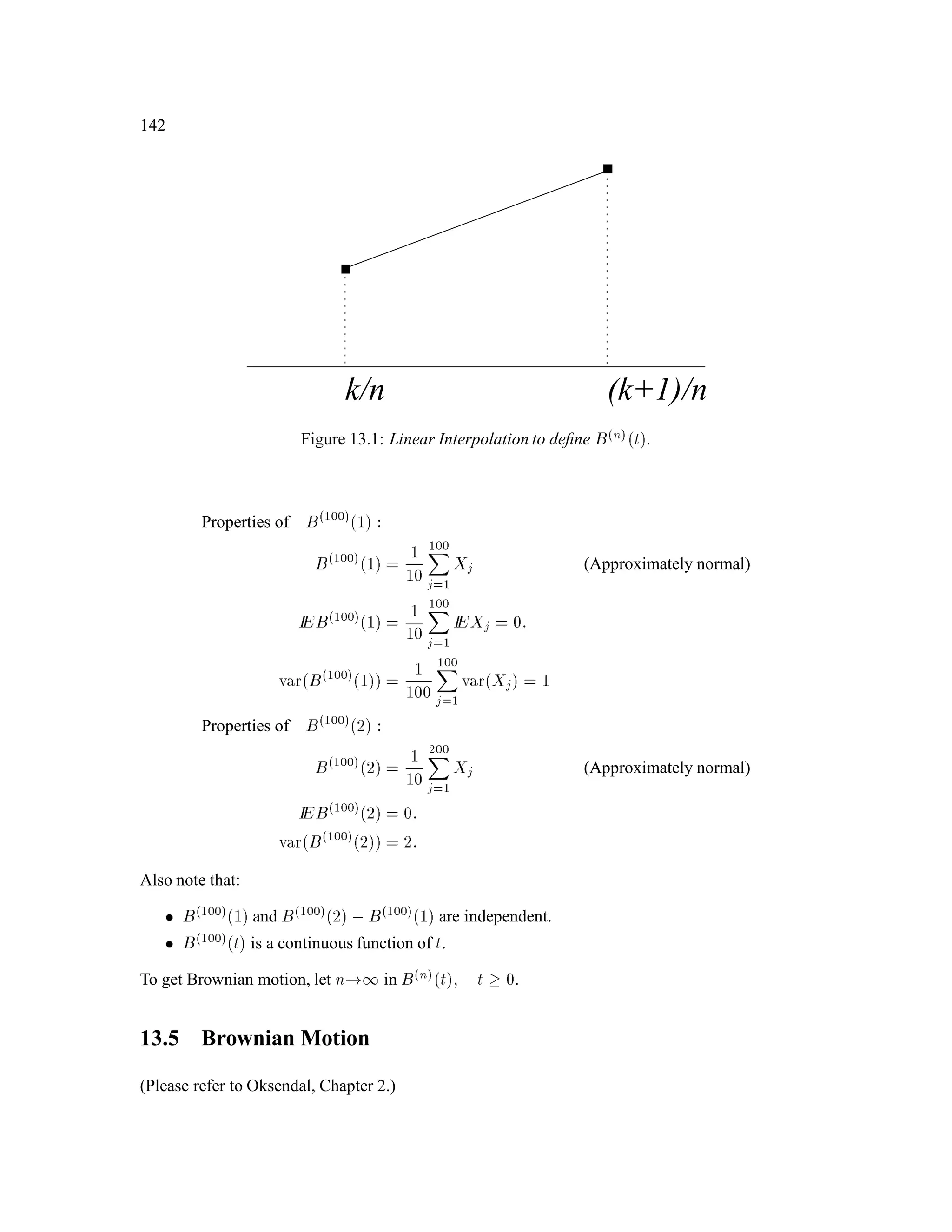

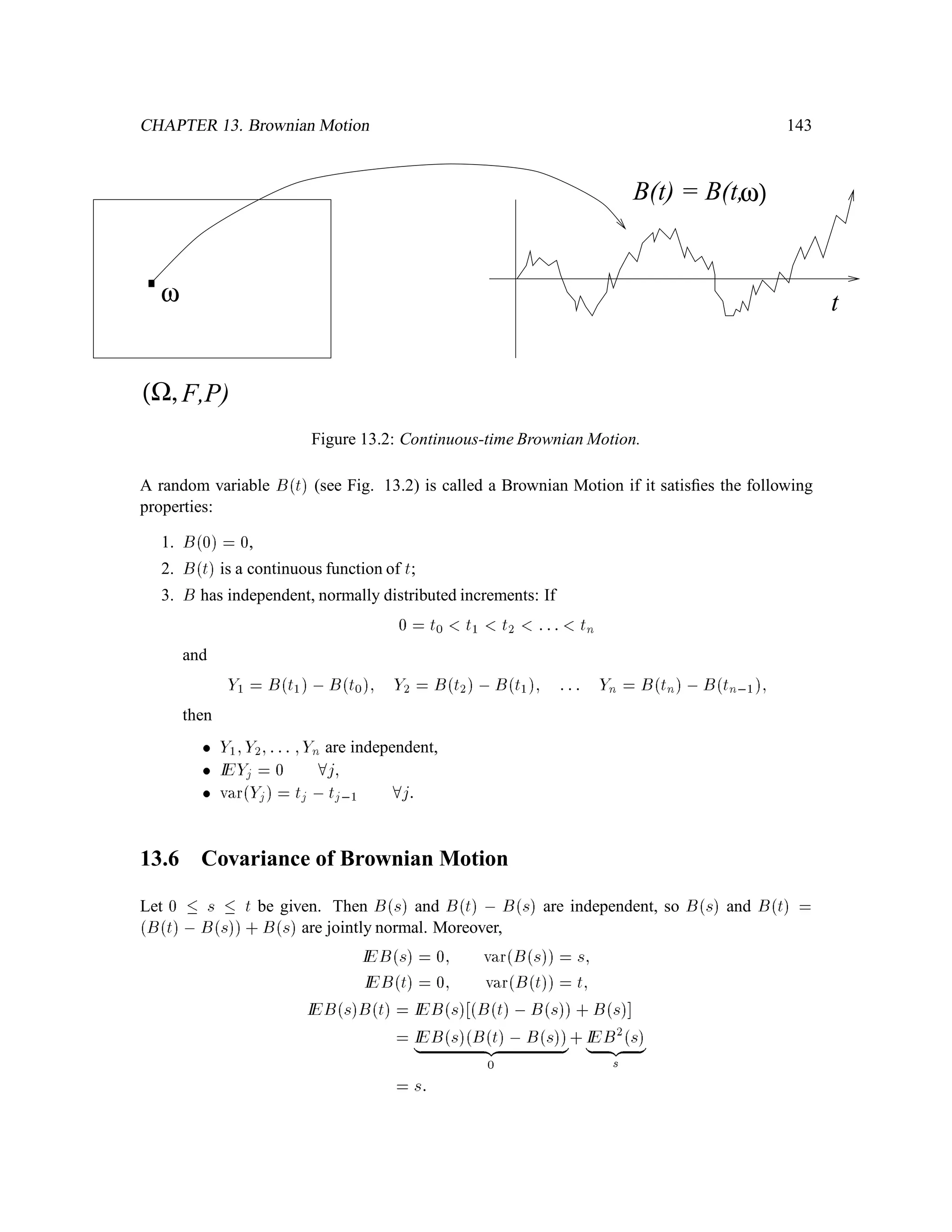

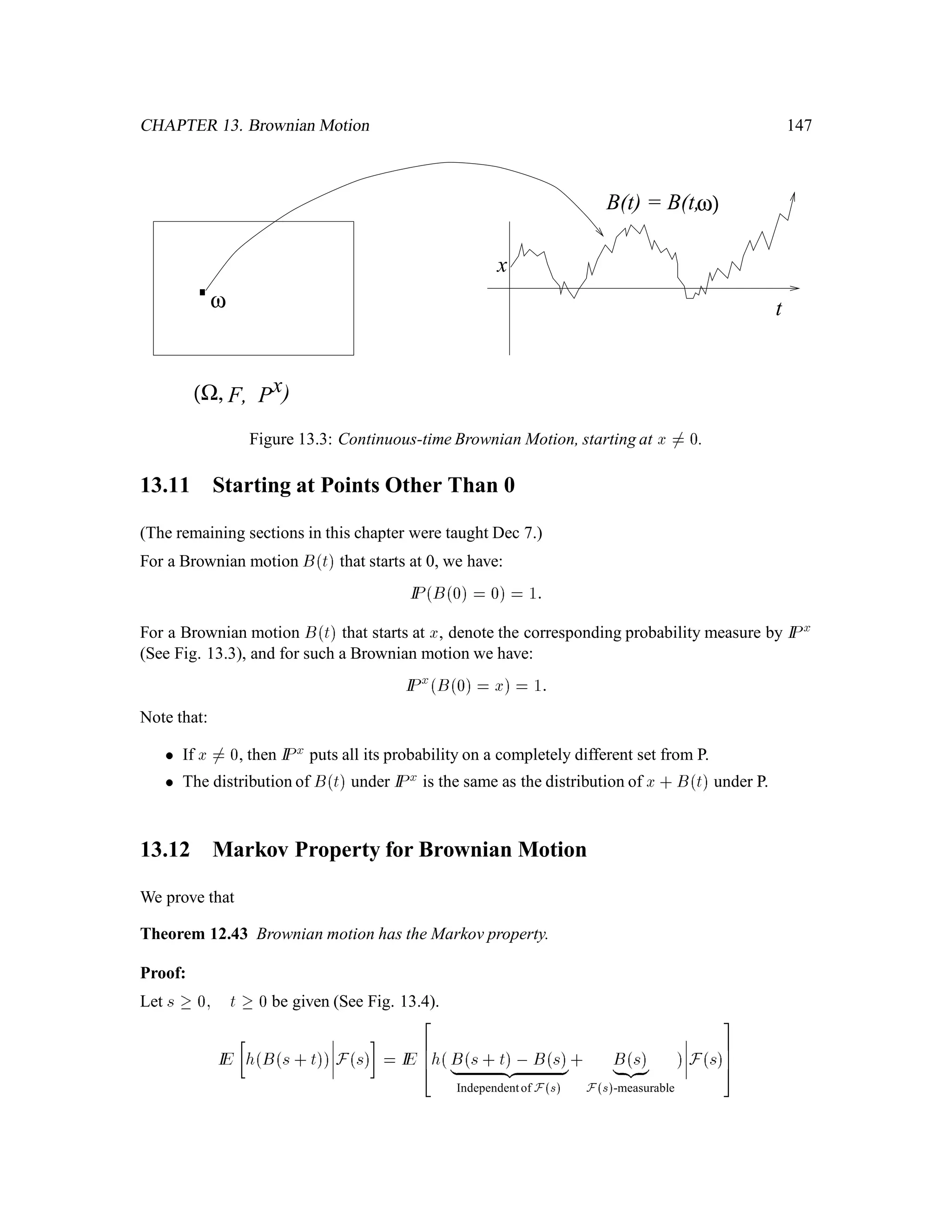

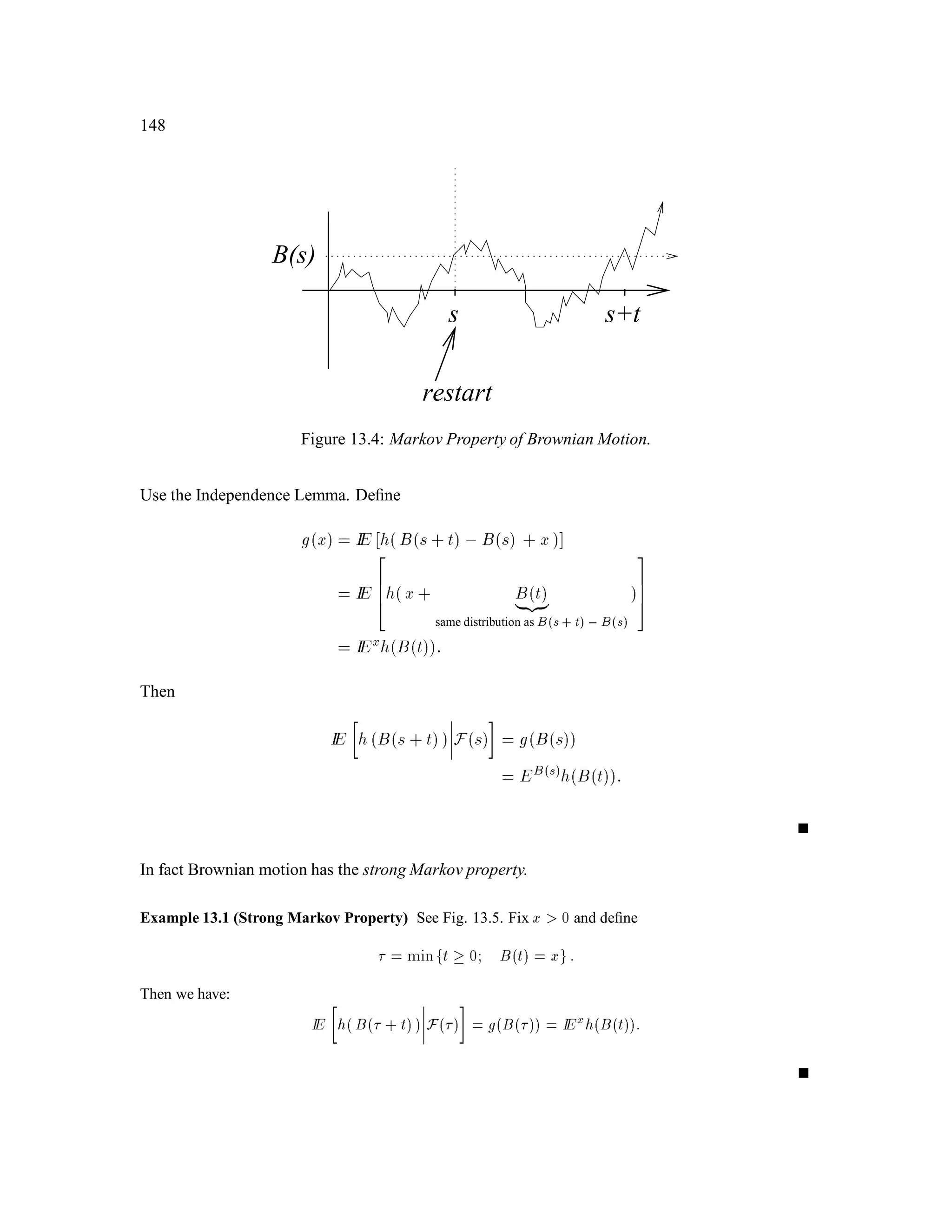

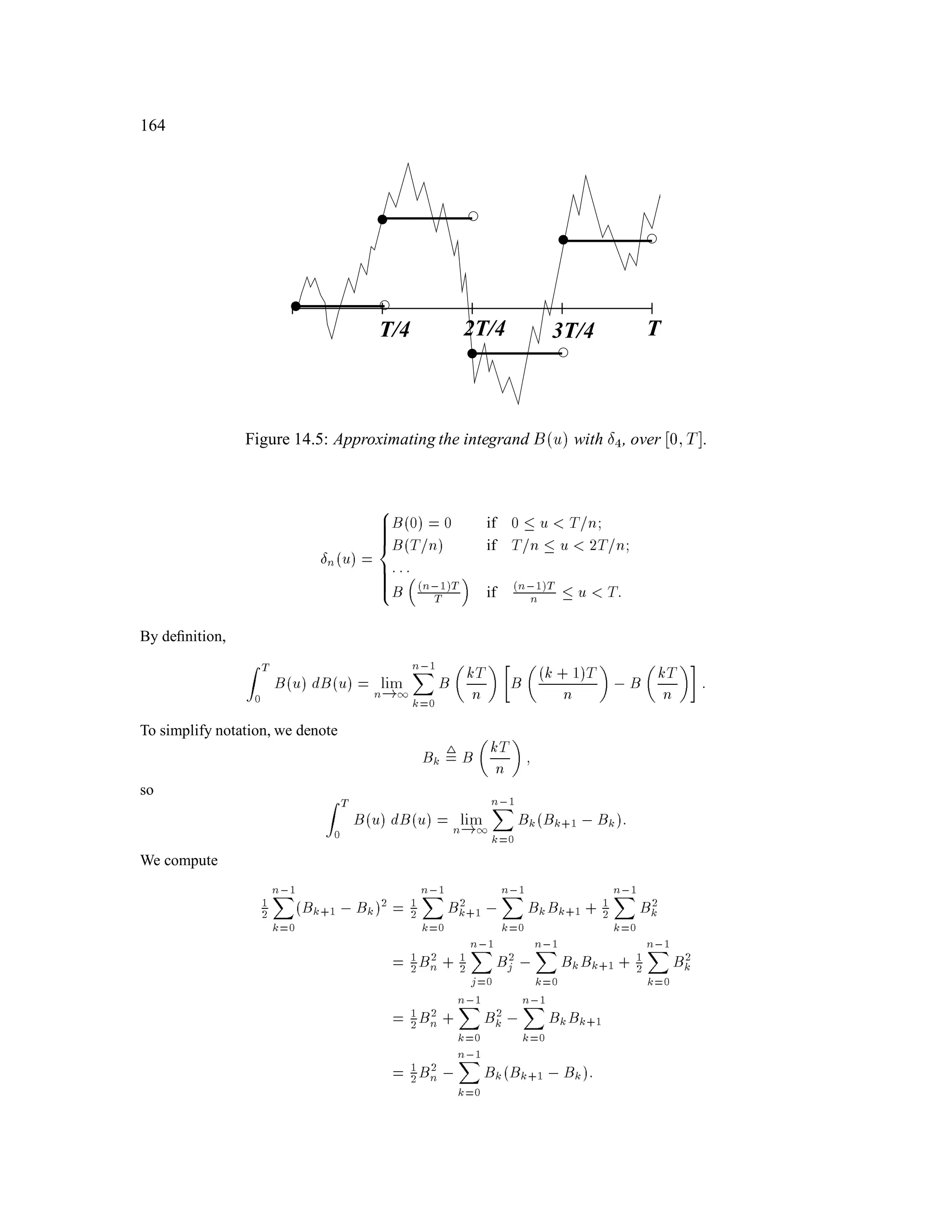

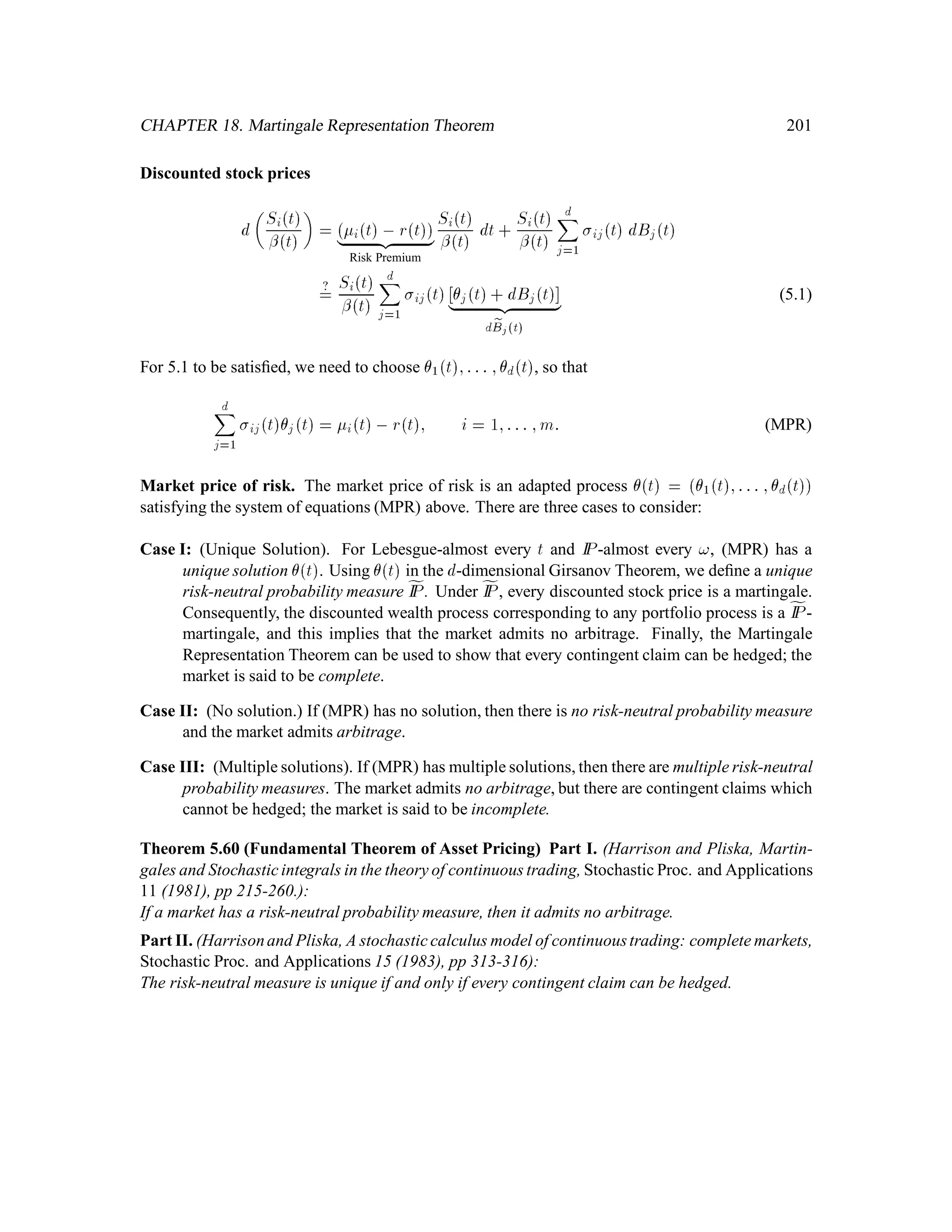

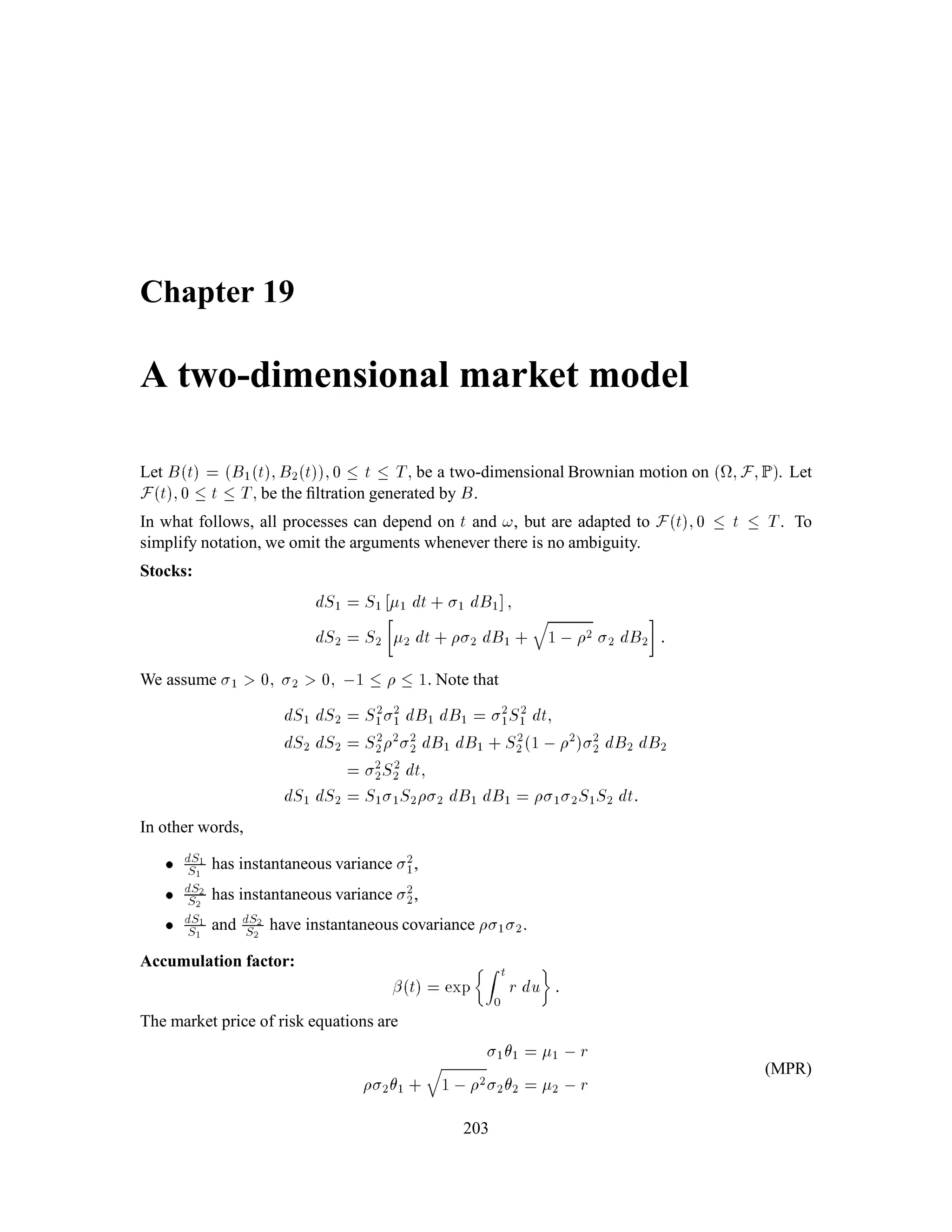

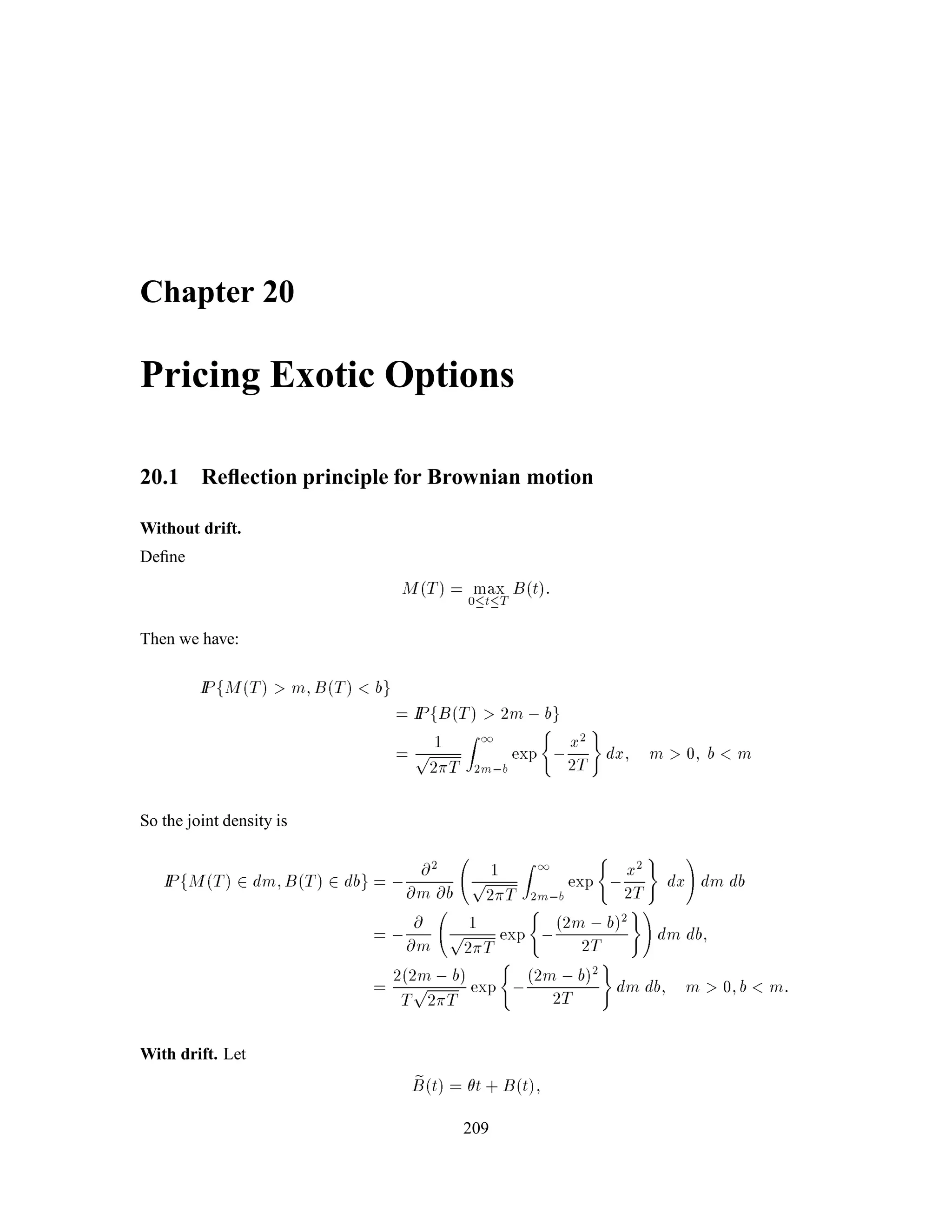

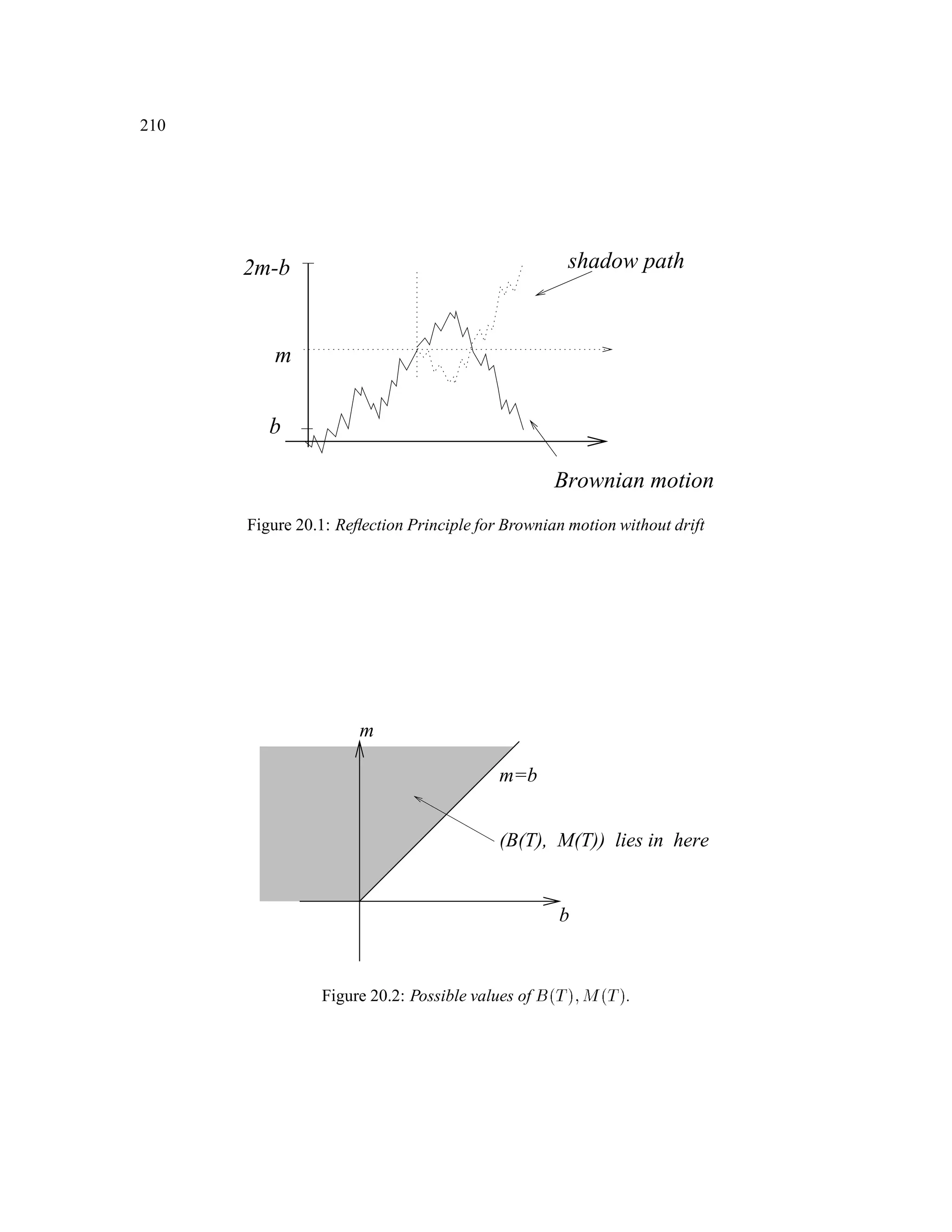

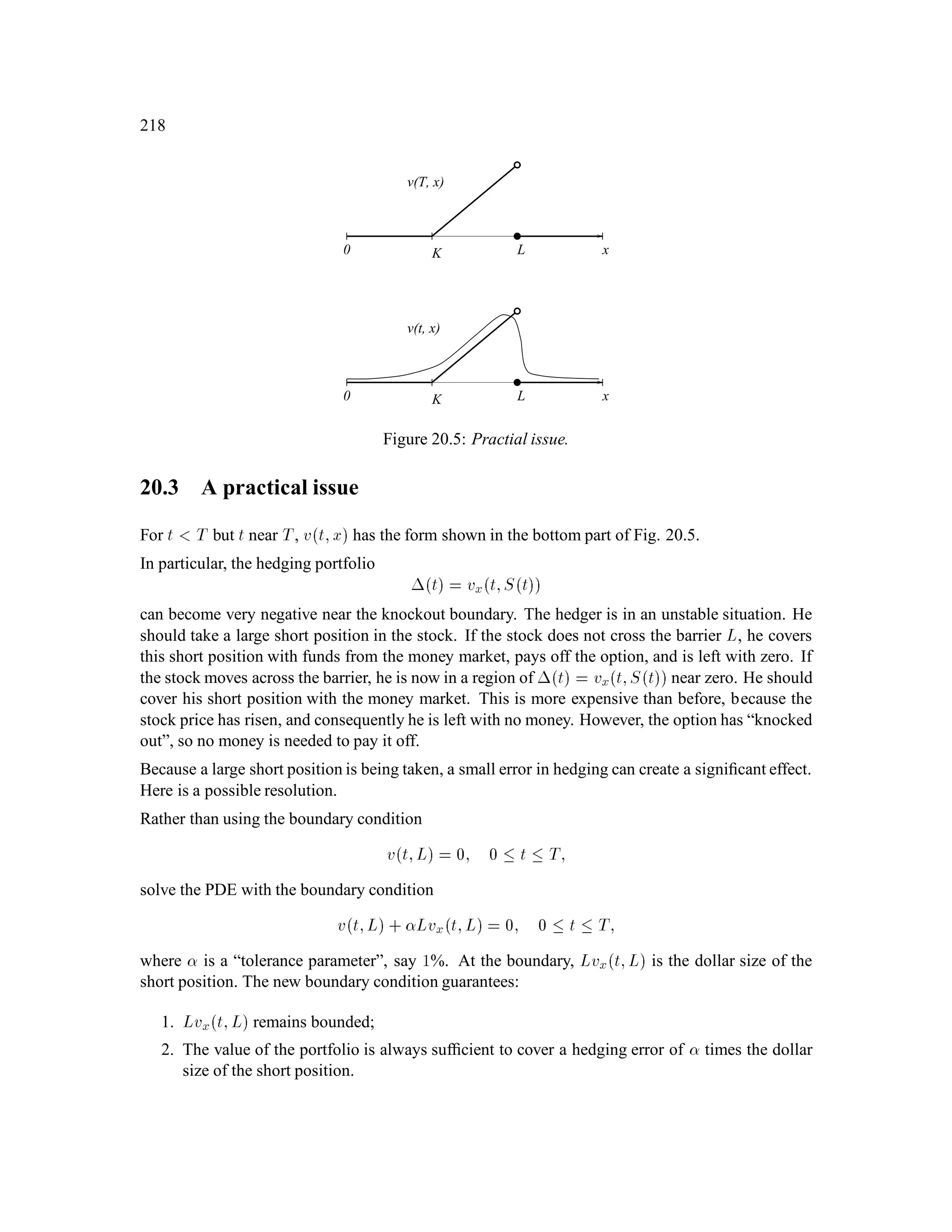

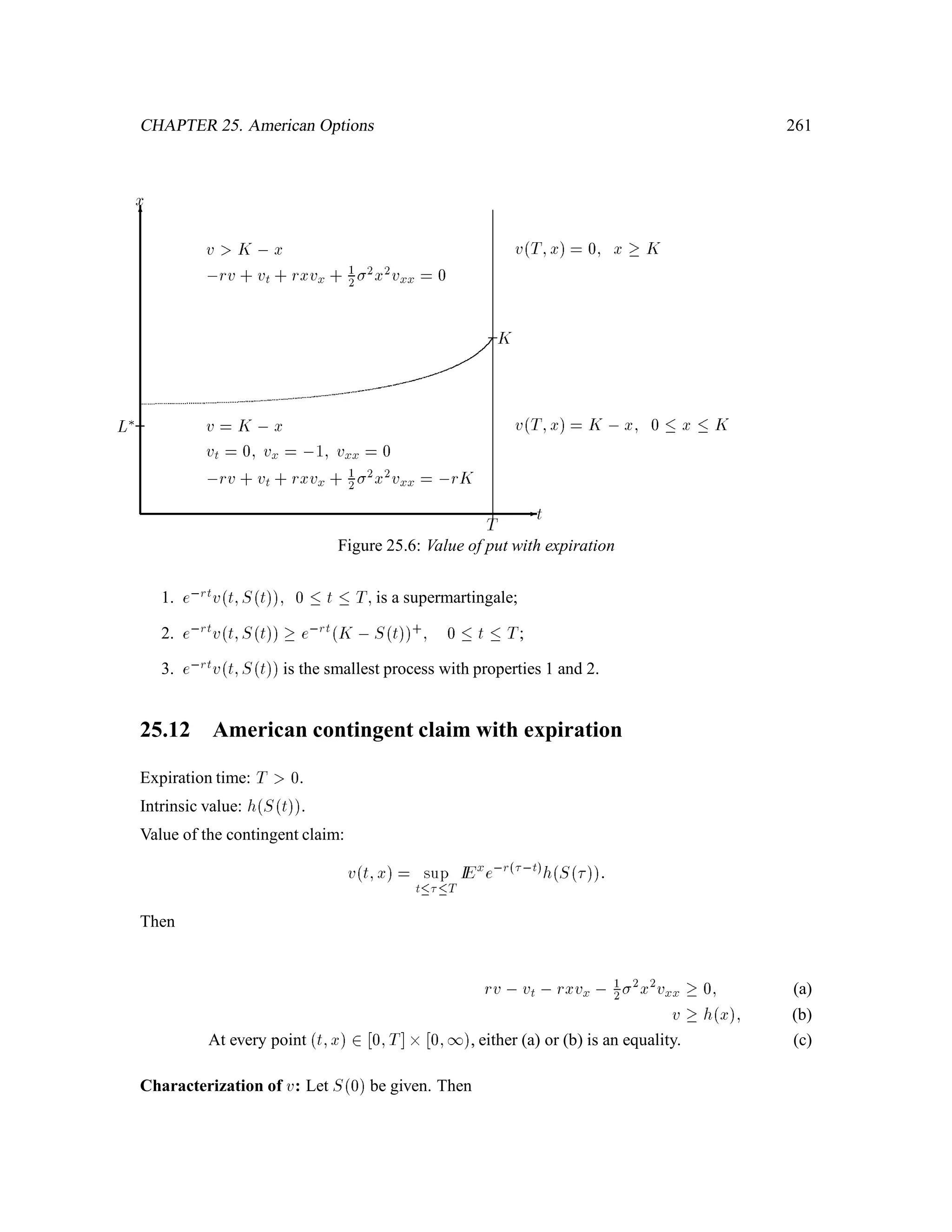

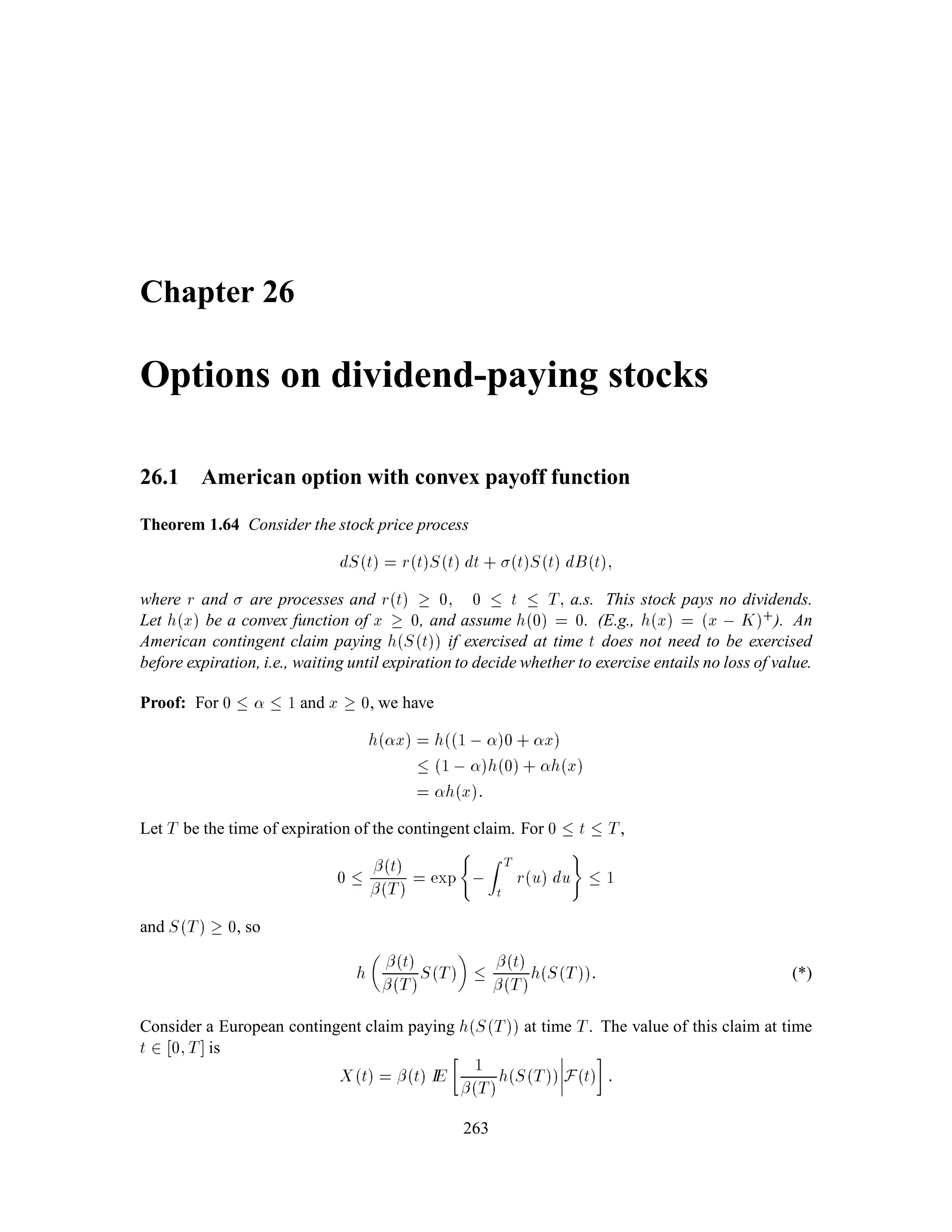

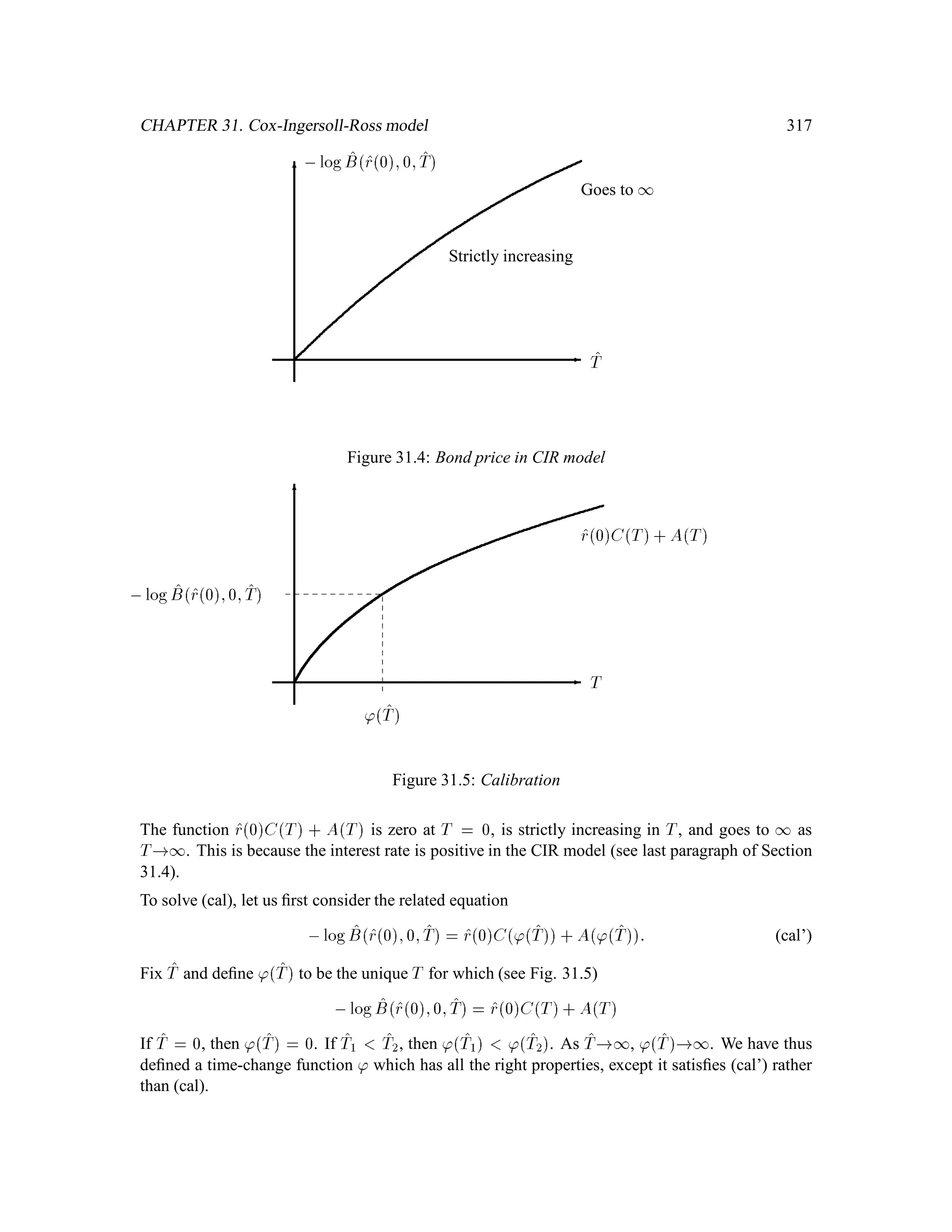

The document is a comprehensive text on stochastic calculus and finance, authored by Steven Shreve and includes contributions from Prasad Chalasani and Somesh Jha. It covers a wide range of topics such as probability theory, conditional expectation, martingales, pricing of derivative securities, and various mathematical models related to finance, including the binomial model and Brownian motion. The content is organized into sections that explore foundational principles and advanced concepts crucial for the understanding of financial mathematics.