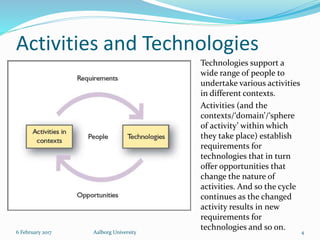

The document discusses the PACT framework for designing interactive systems, which focuses on analyzing People, Activities, Contexts, and Technologies. It describes how to conduct a PACT analysis to understand the variety of users, tasks, environments, and technological requirements. The analysis involves scoping out the different factors through methods like brainstorming, observations, and interviews to inform the design process.