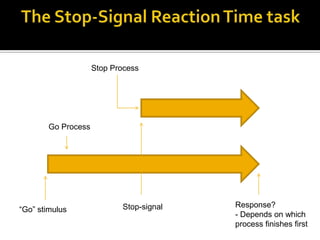

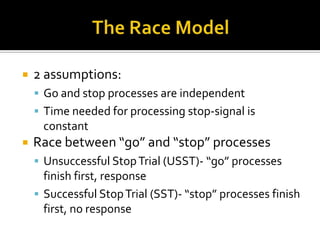

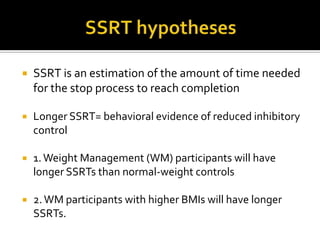

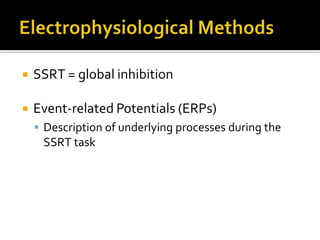

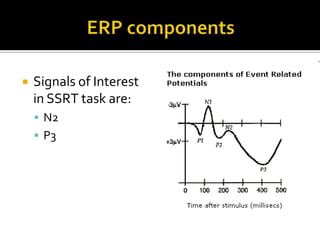

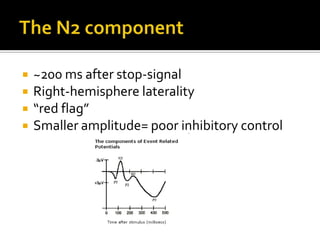

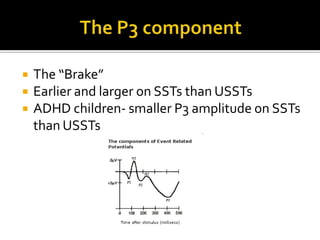

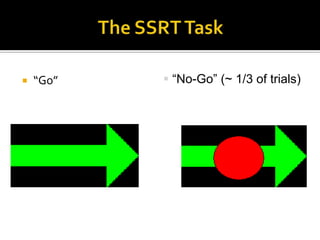

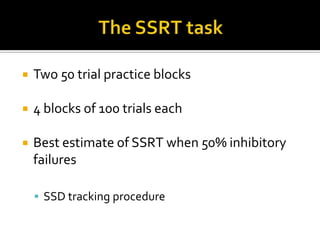

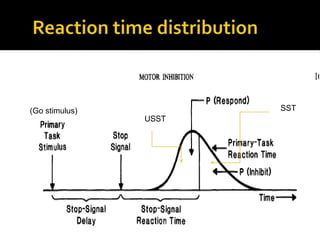

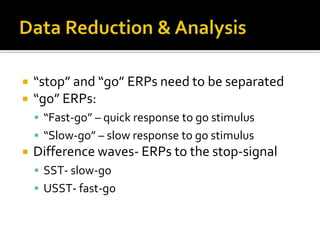

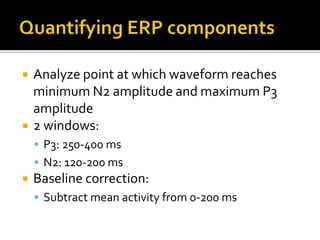

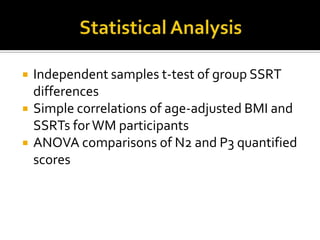

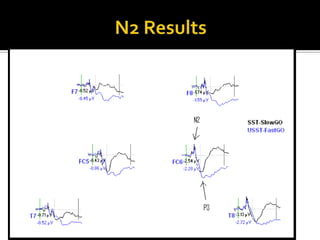

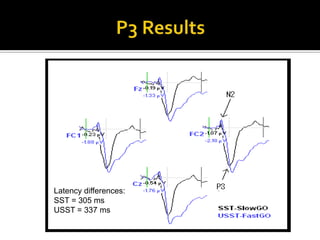

This document summarizes research investigating potential differences in inhibitory control between overweight children and normal-weight controls using electrophysiological measures. The study used a stop-signal reaction time task to measure inhibitory control and analyzed event-related potentials (ERPs), specifically the N2 and P3 components. Behavioral results found no significant differences in stop-signal reaction times between groups. ERP results found no significant group differences in the amplitude of the N2 or P3 components. However, the P3 component occurred earlier for successful stop trials compared to unsuccessful stop trials overall. The study had limitations due to small sample sizes and discusses avenues for future research.