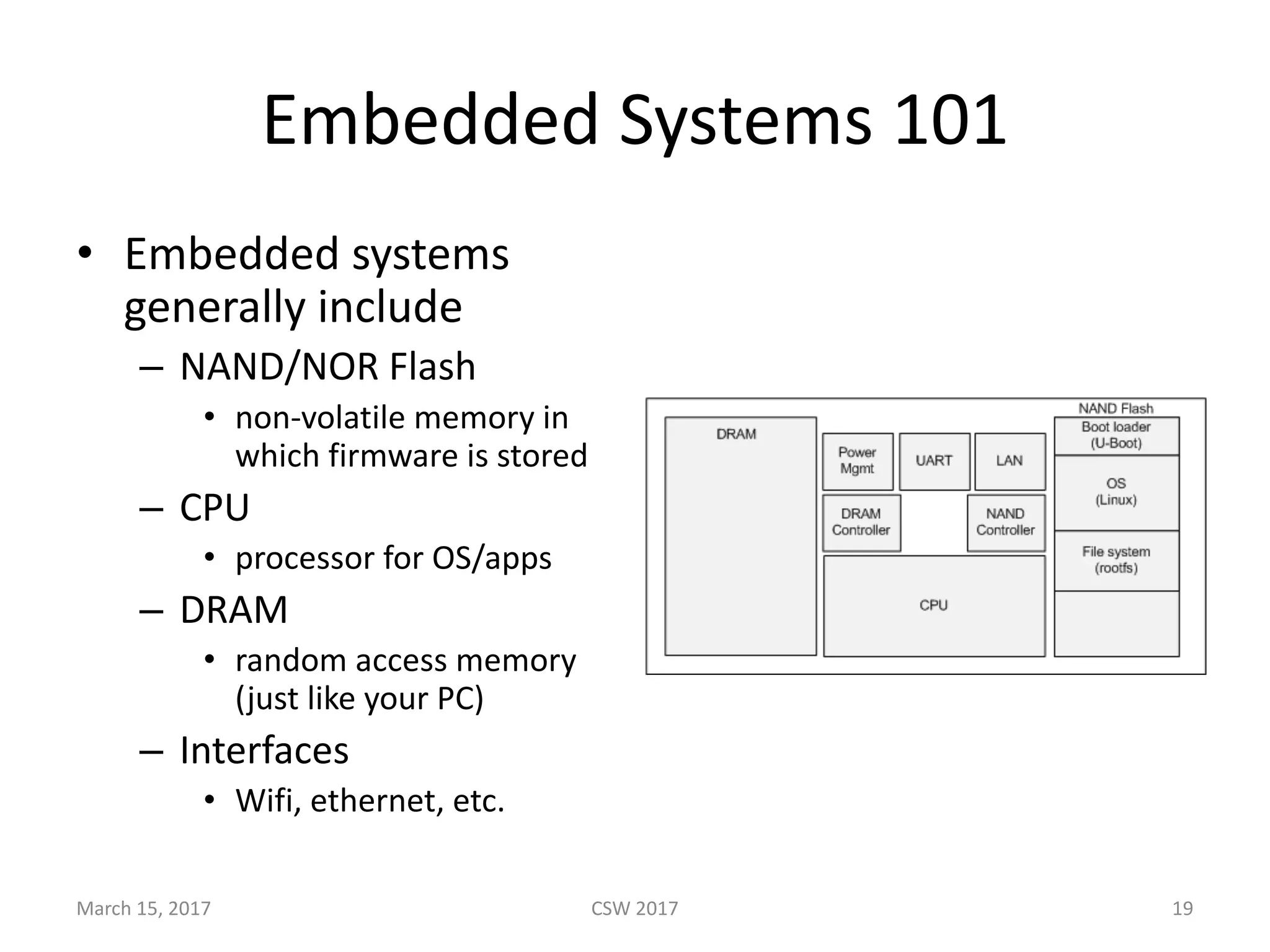

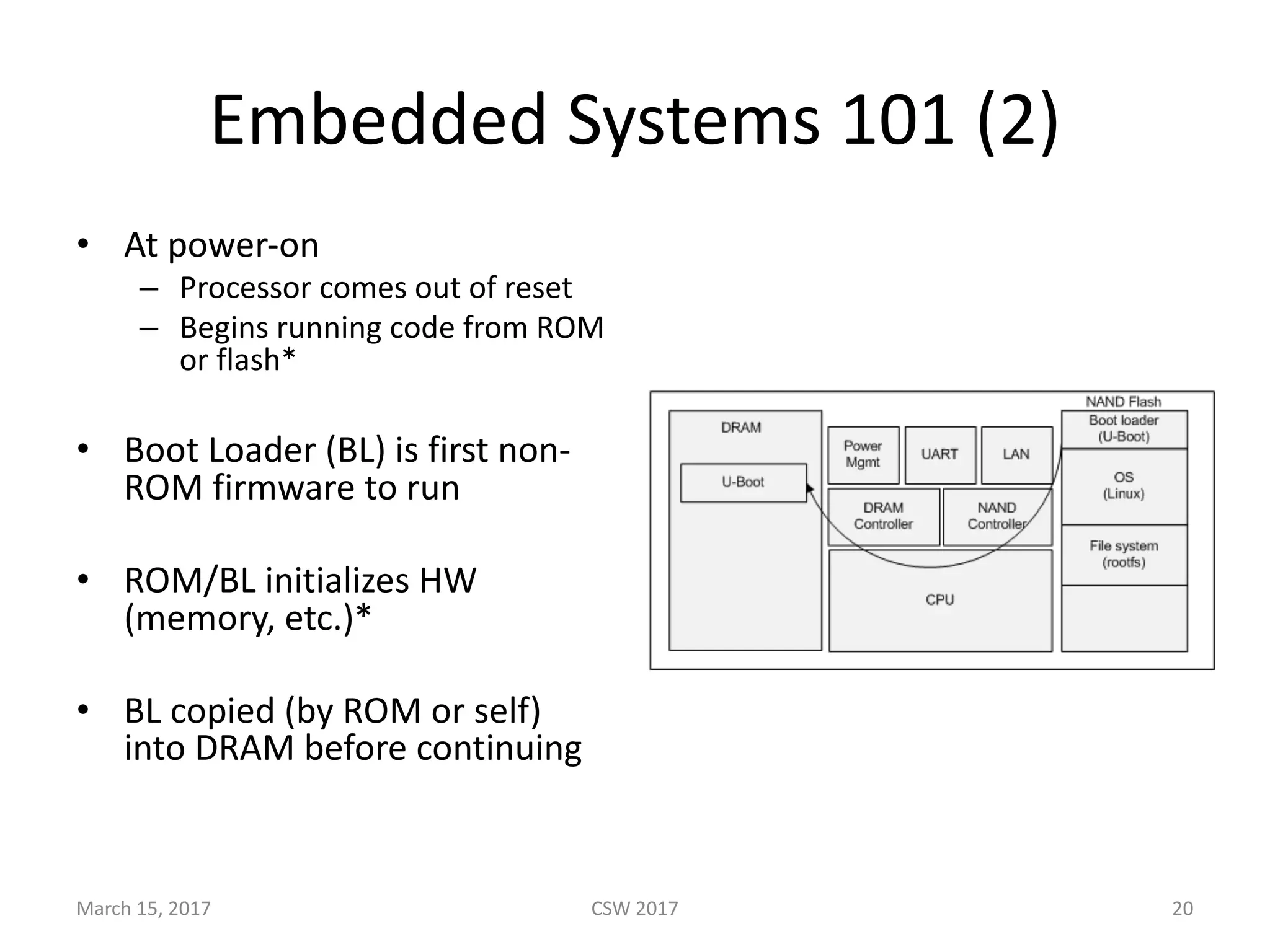

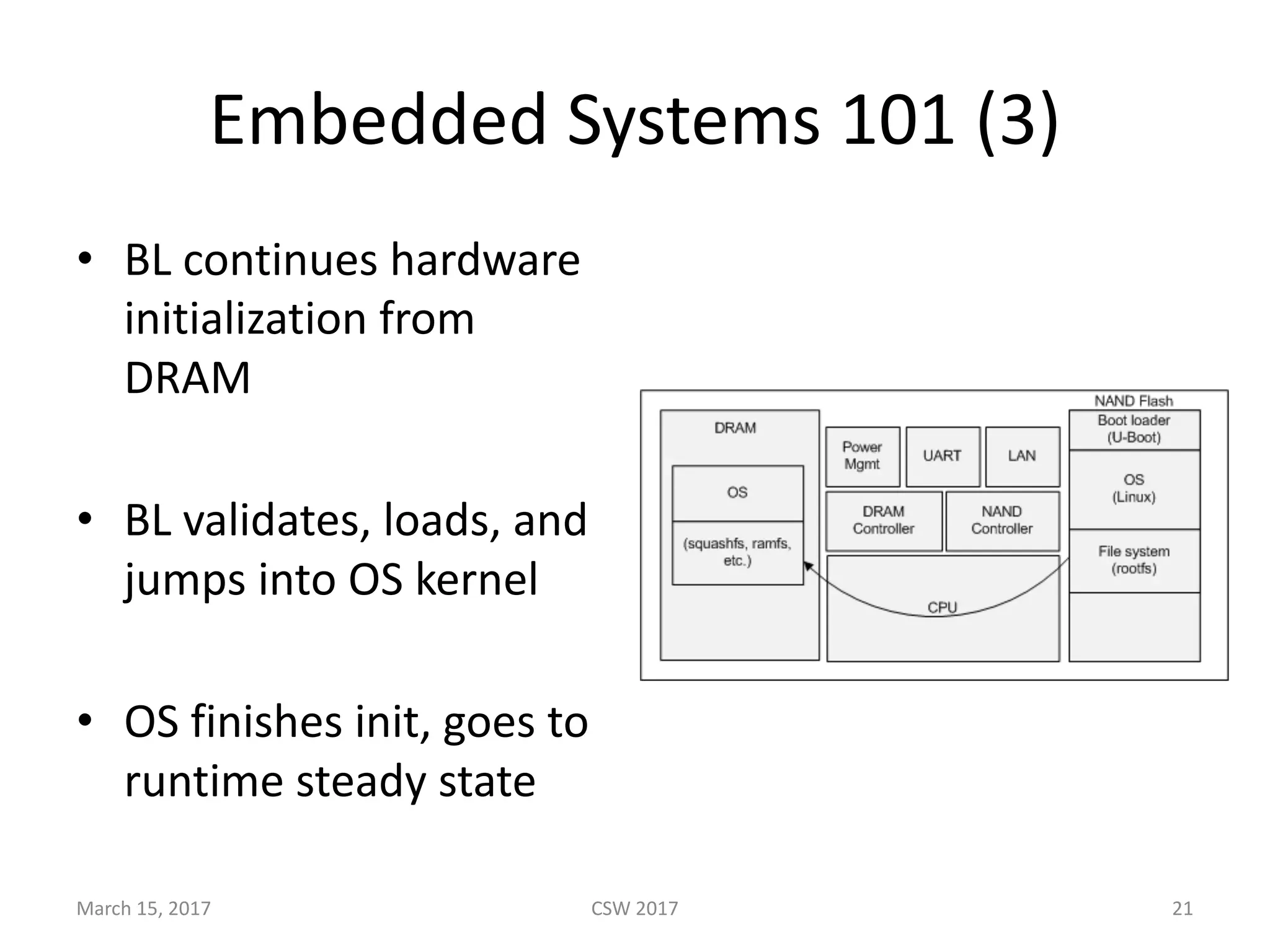

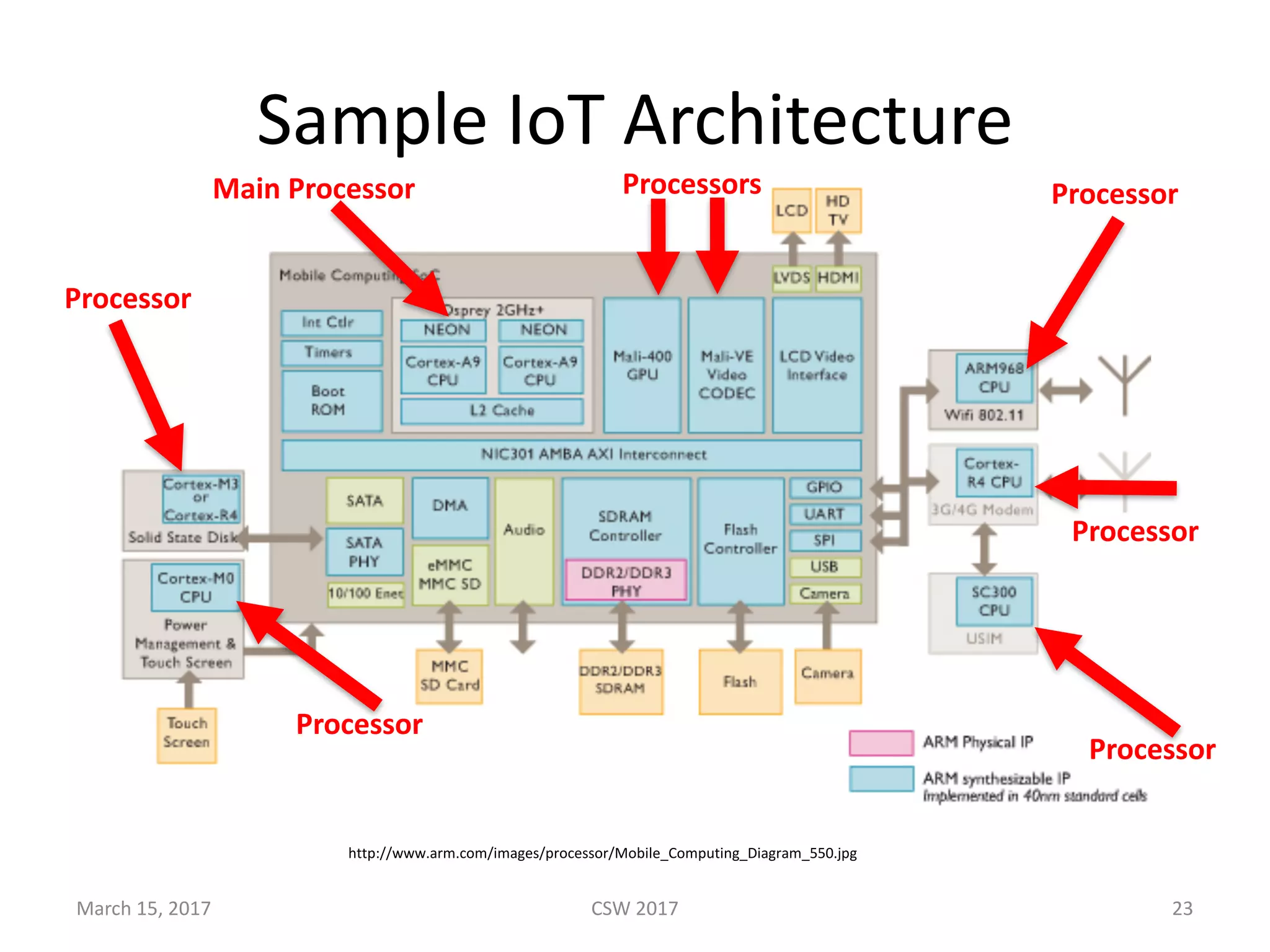

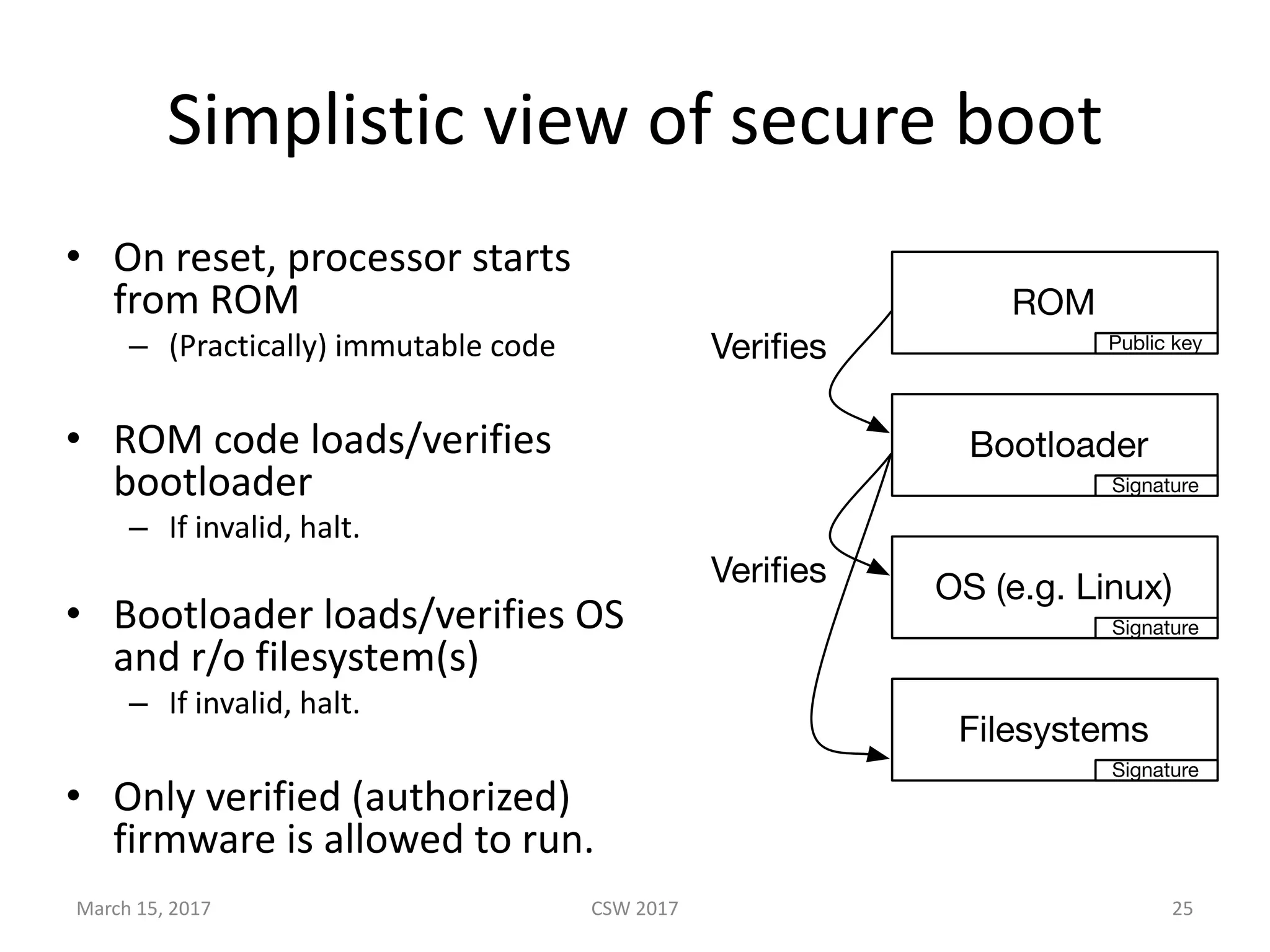

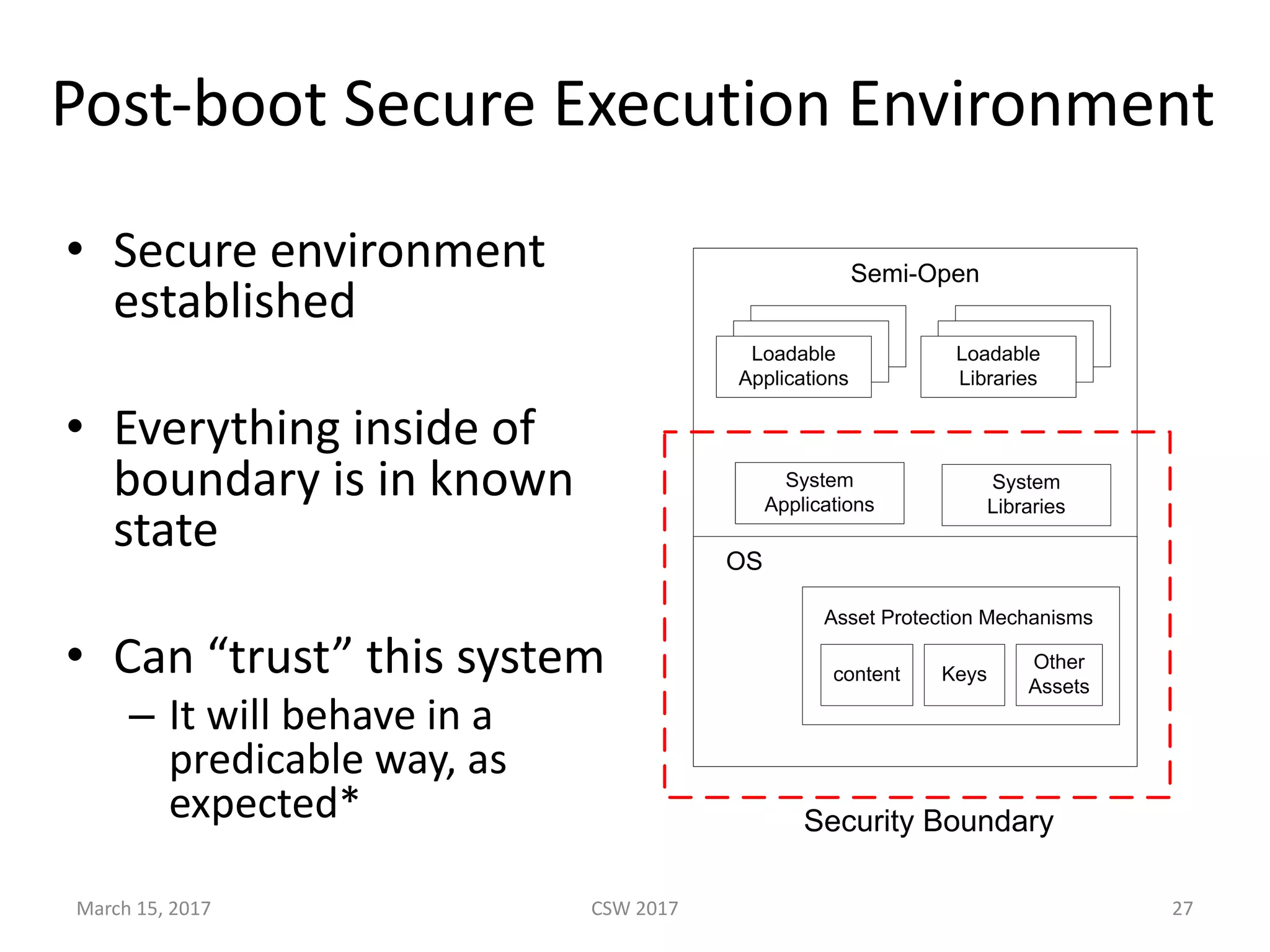

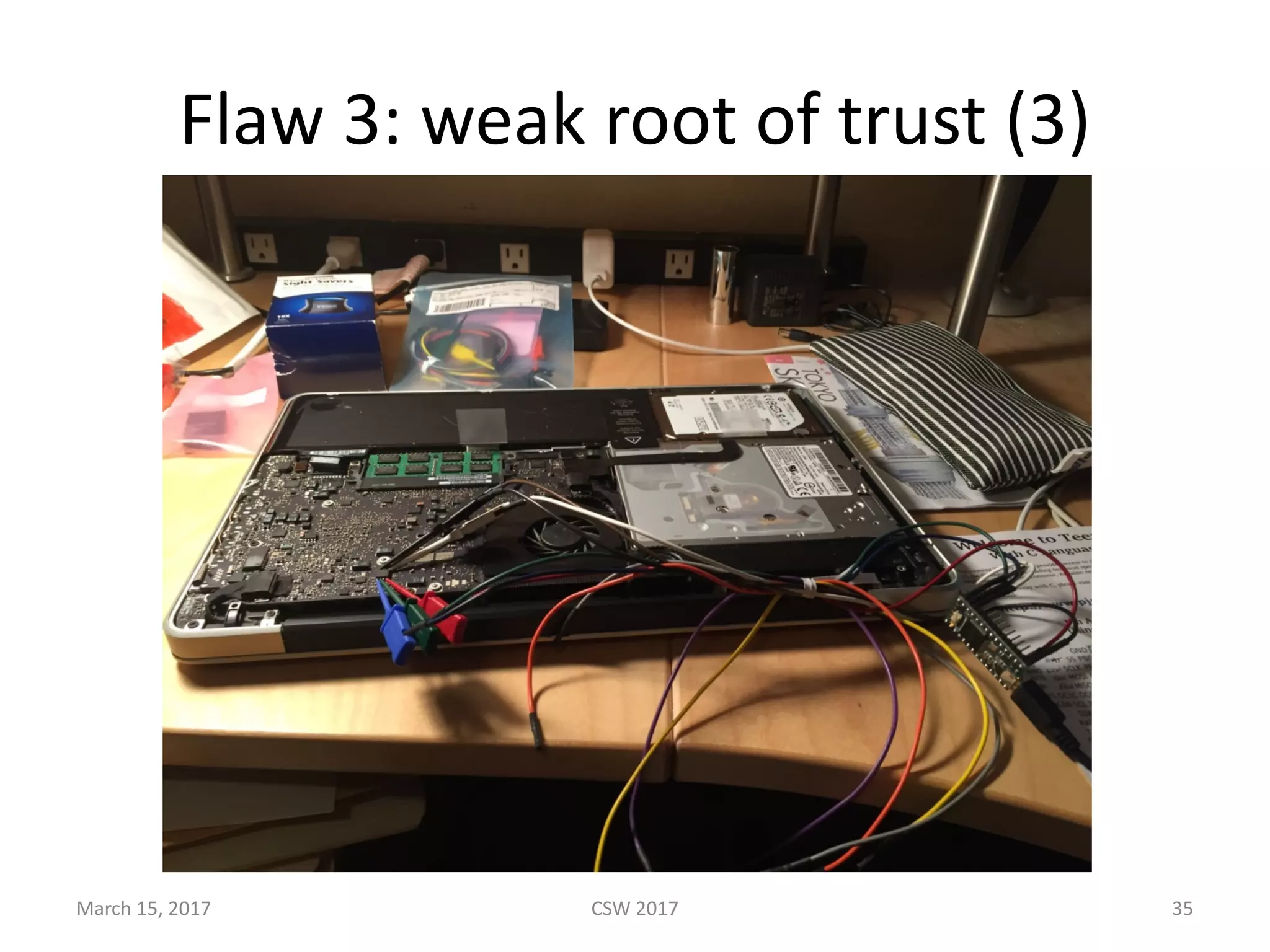

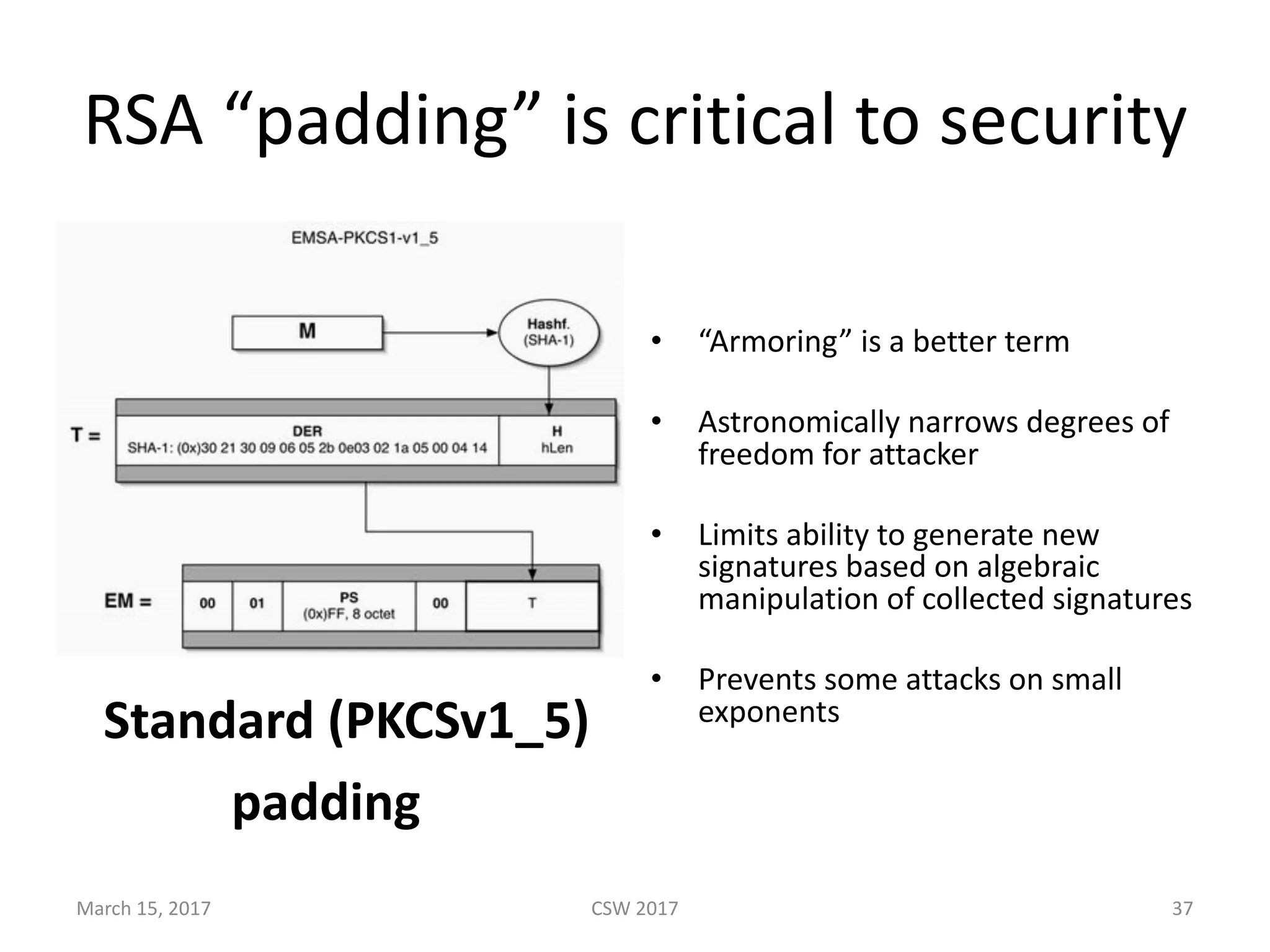

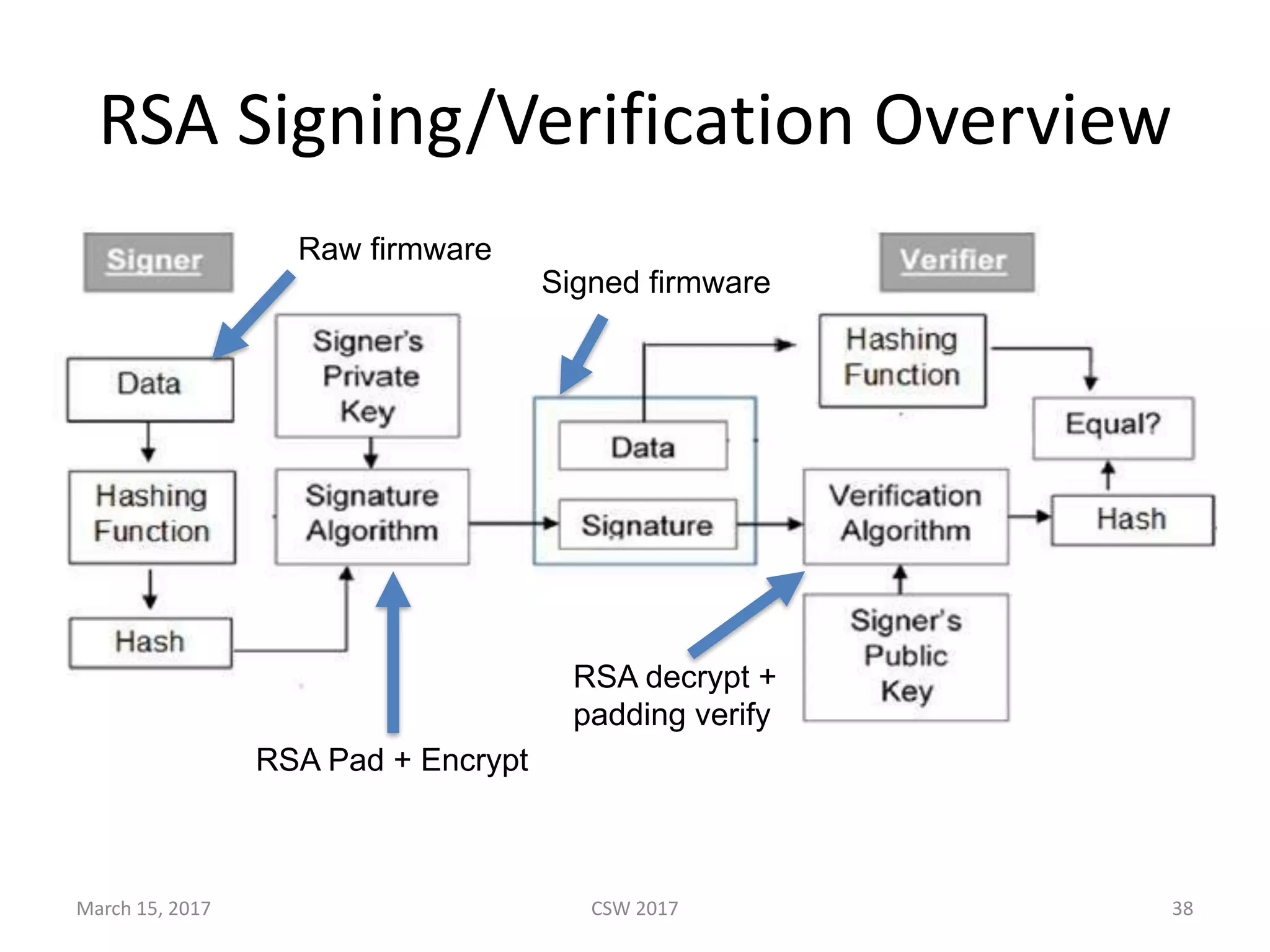

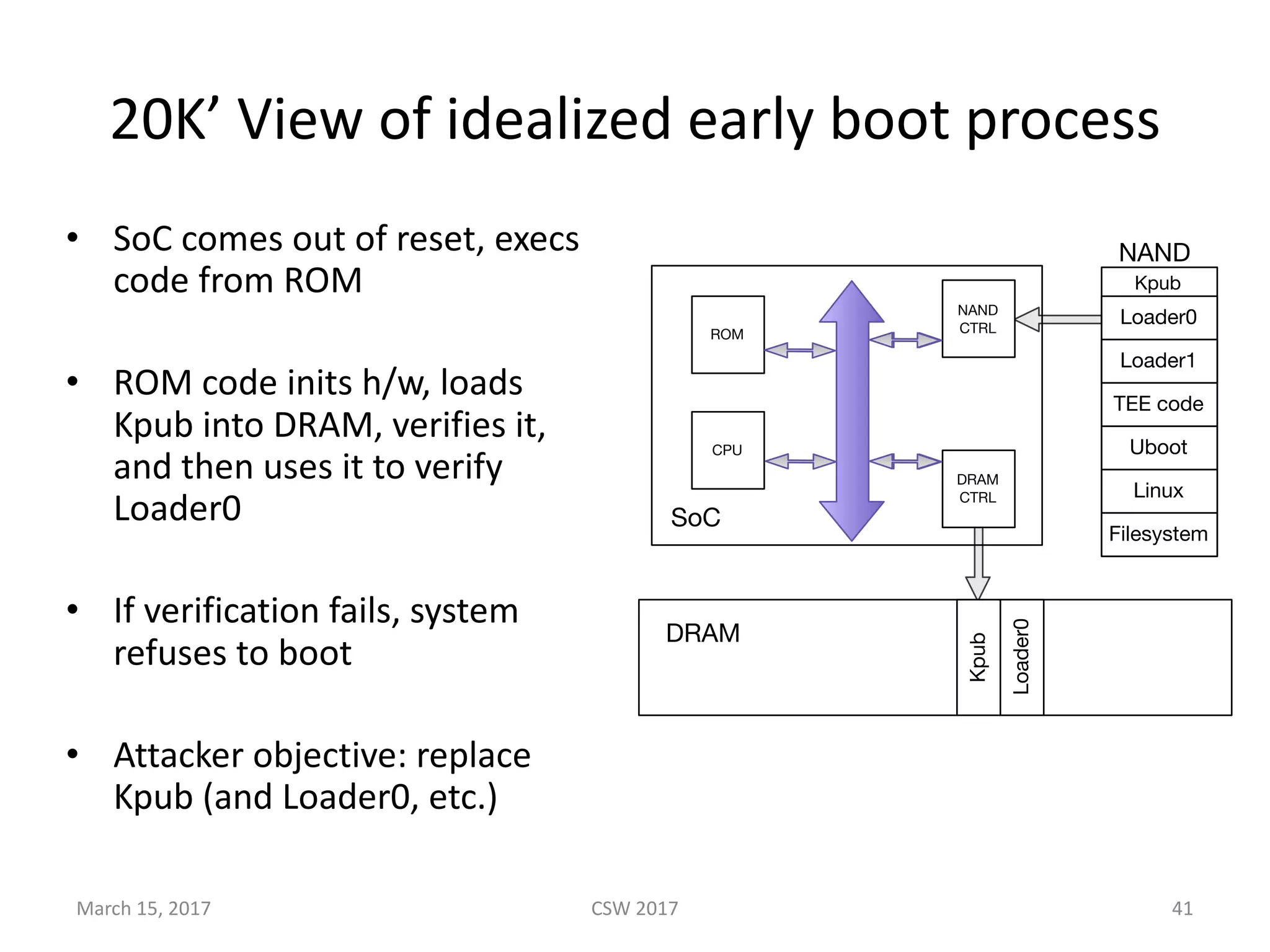

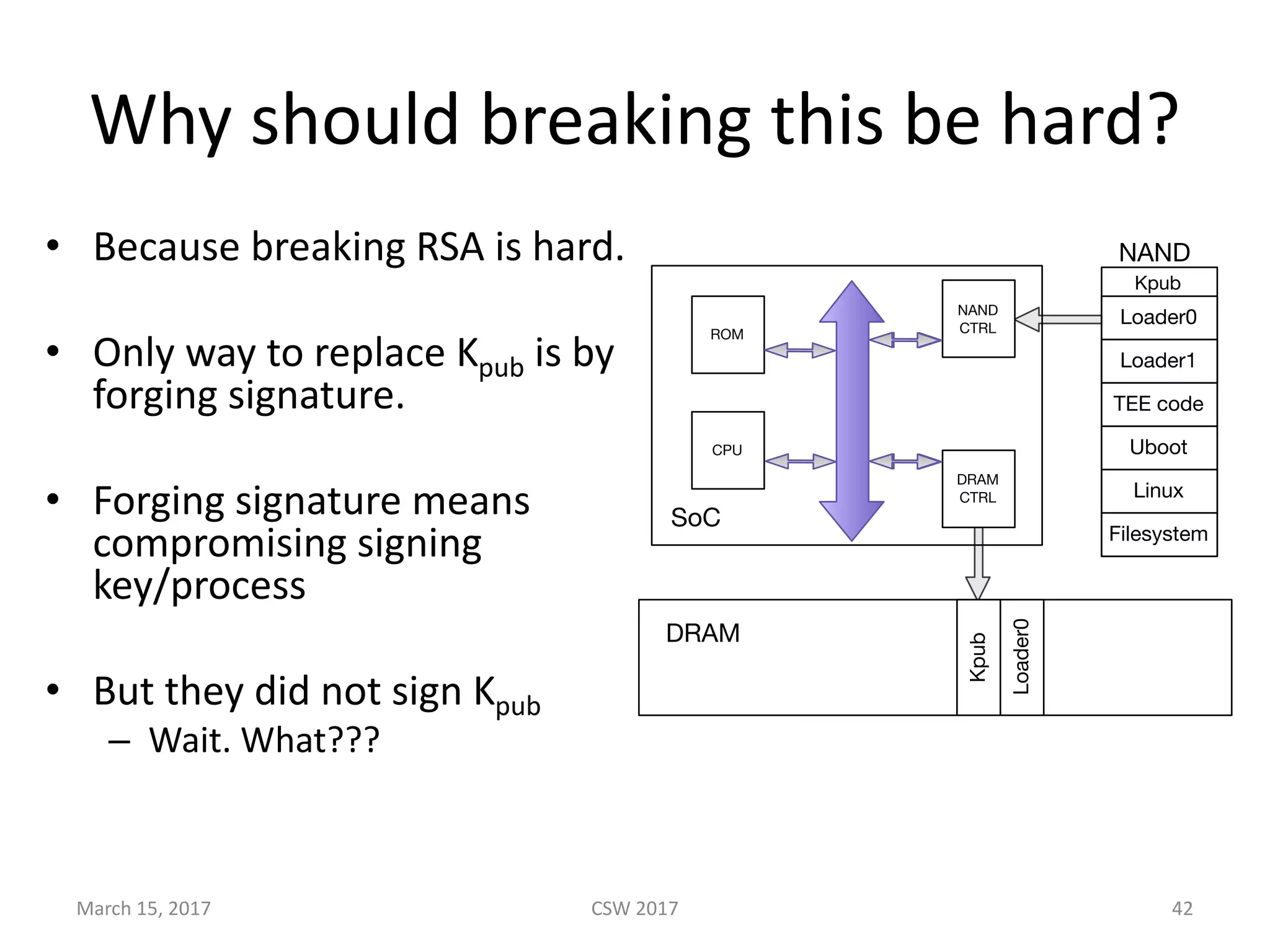

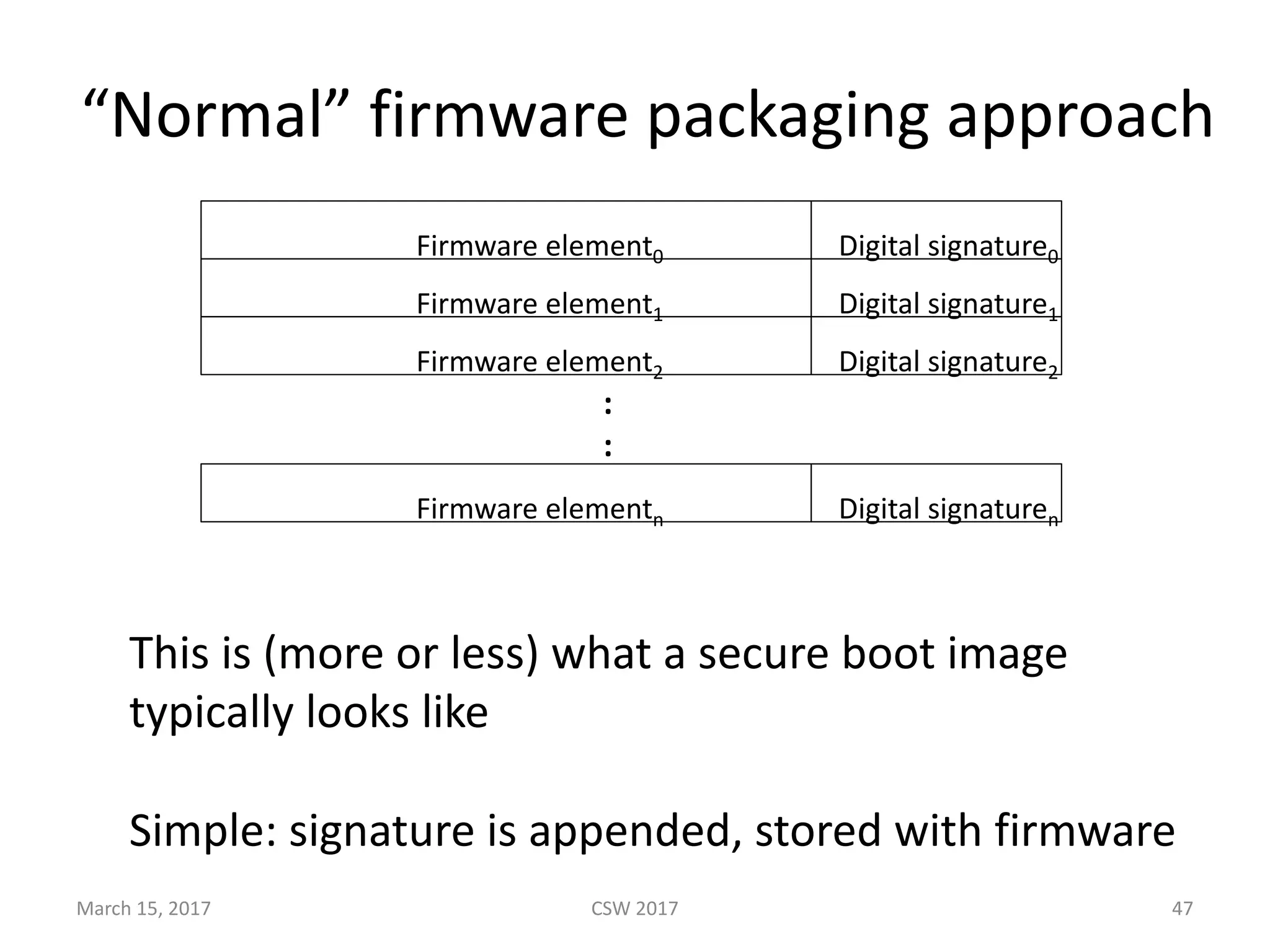

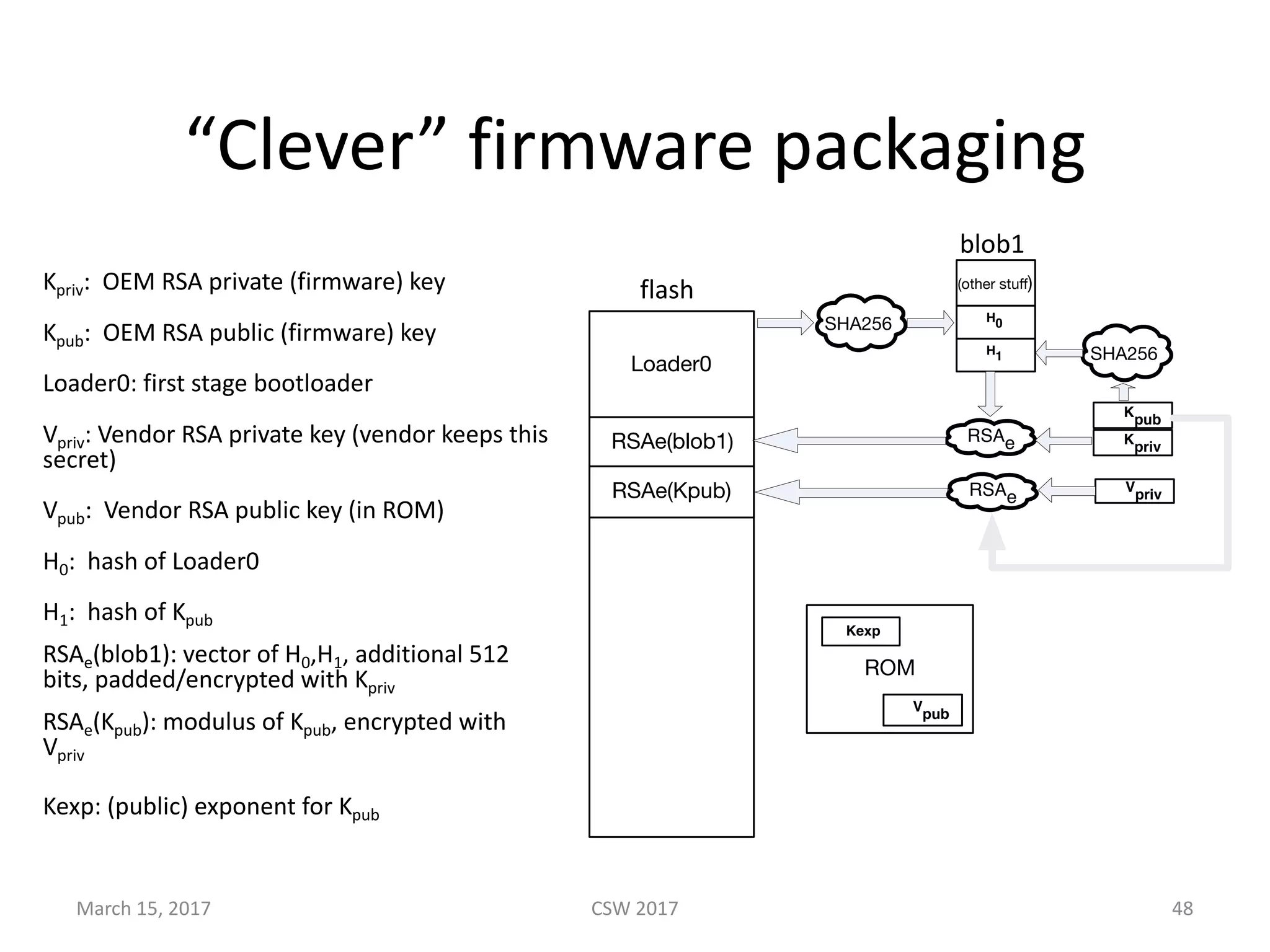

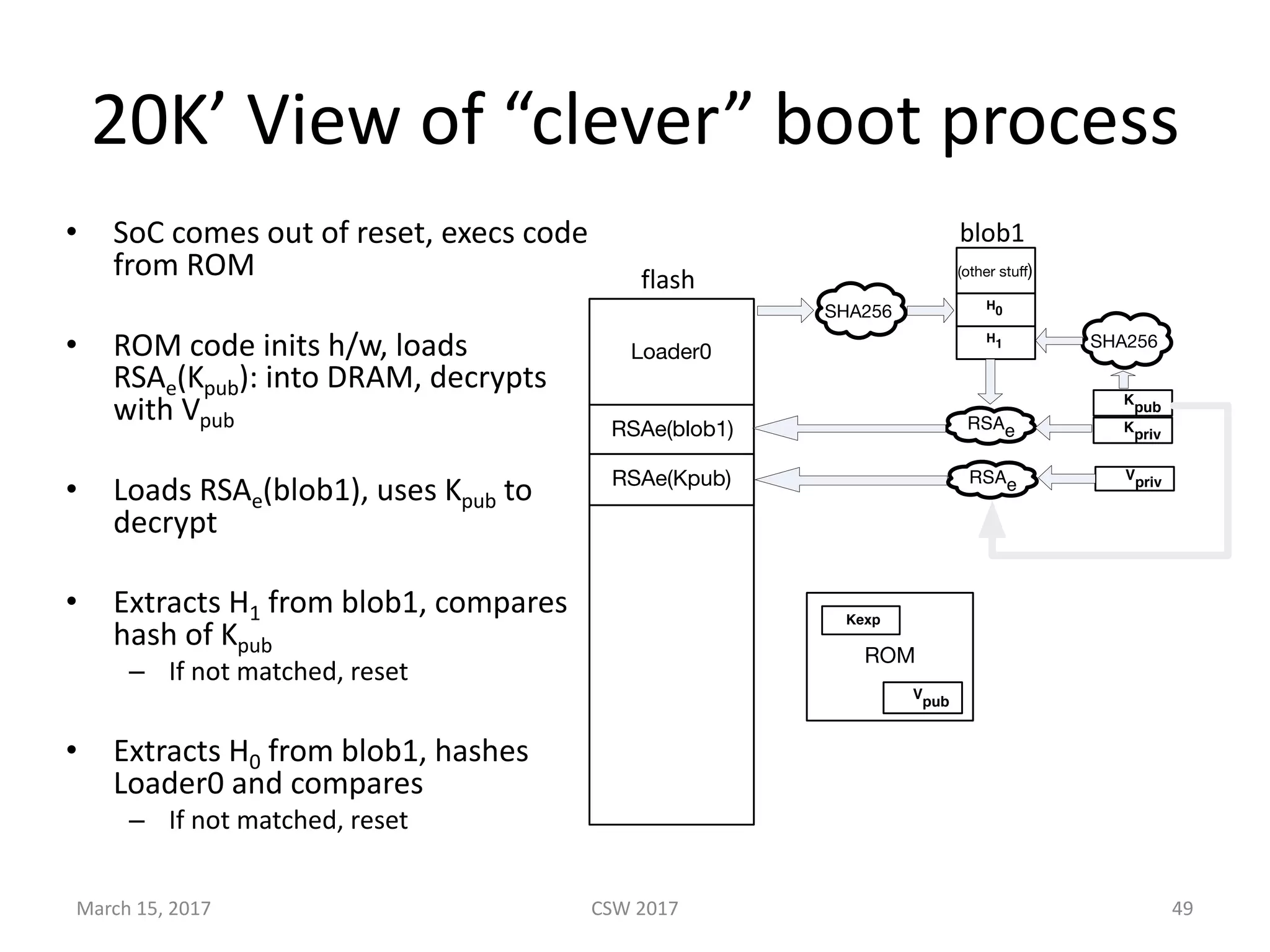

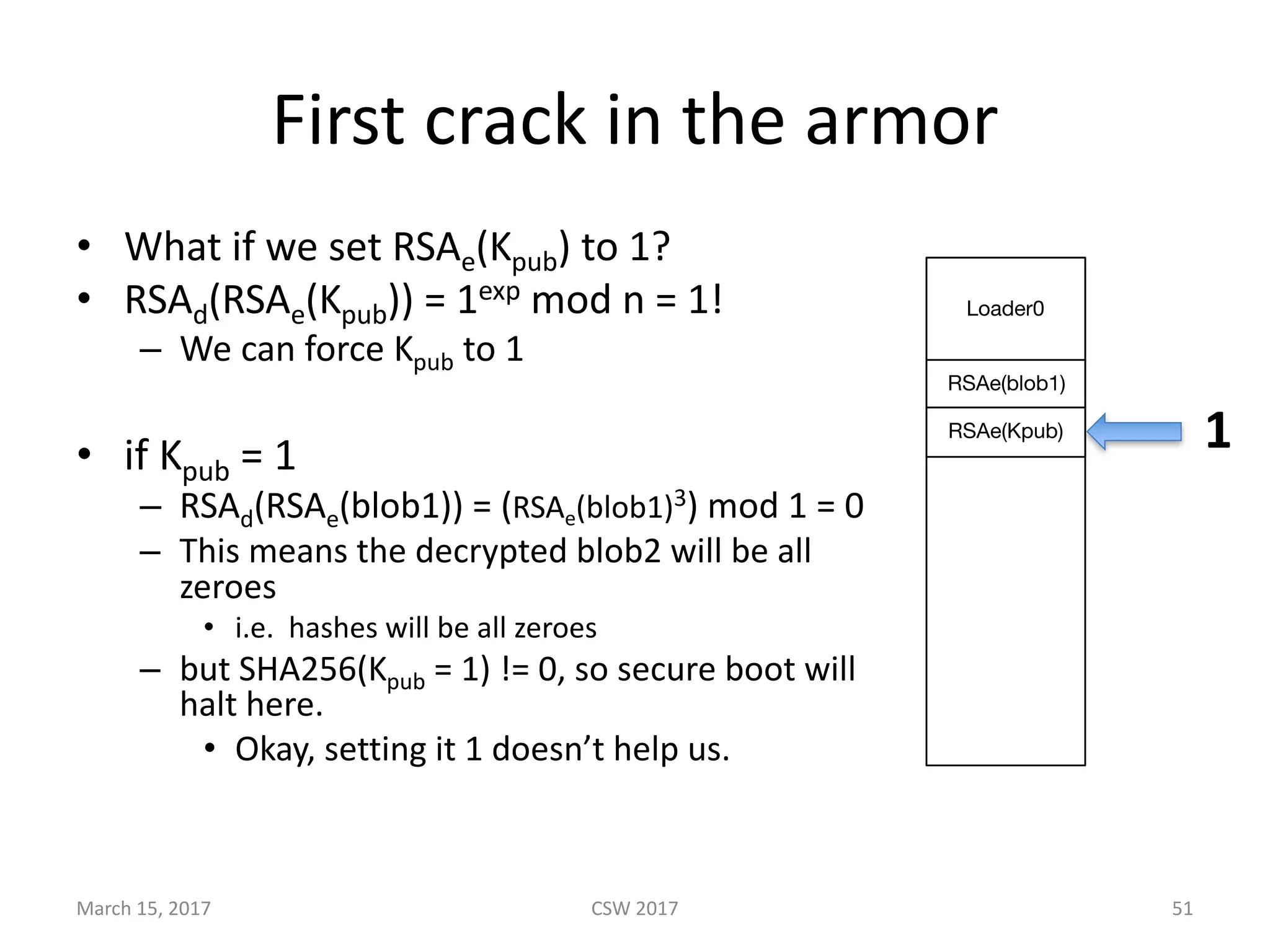

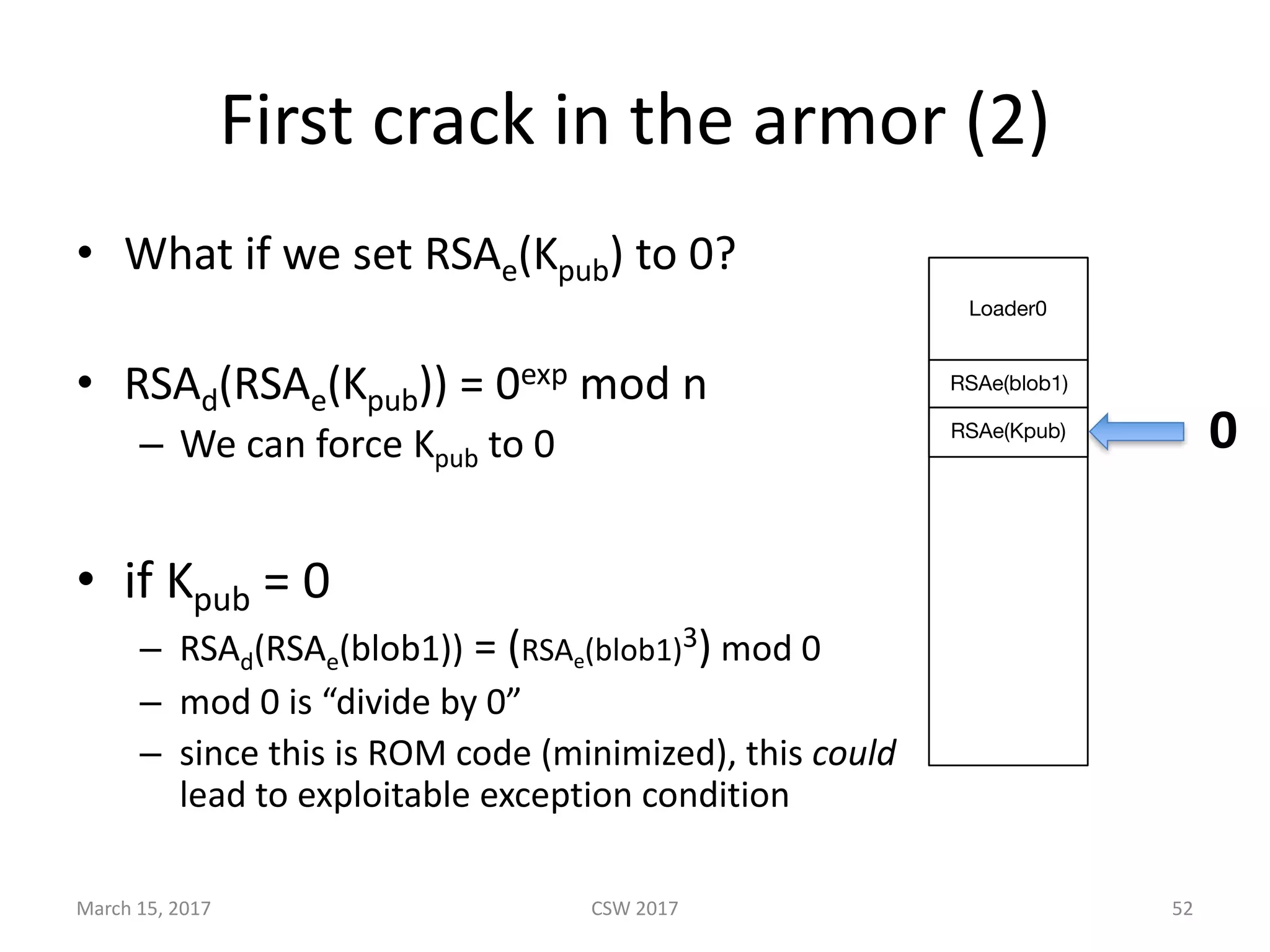

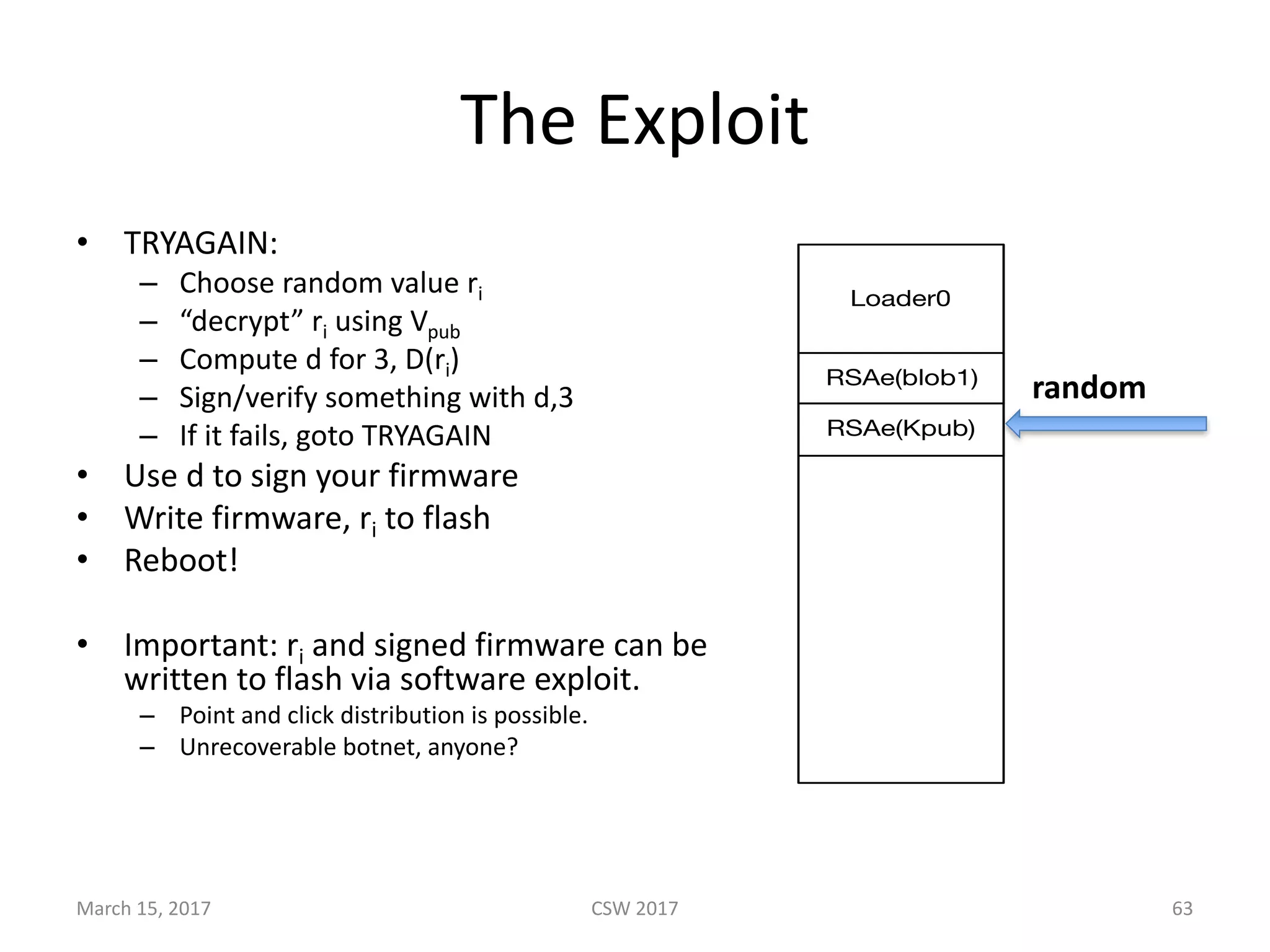

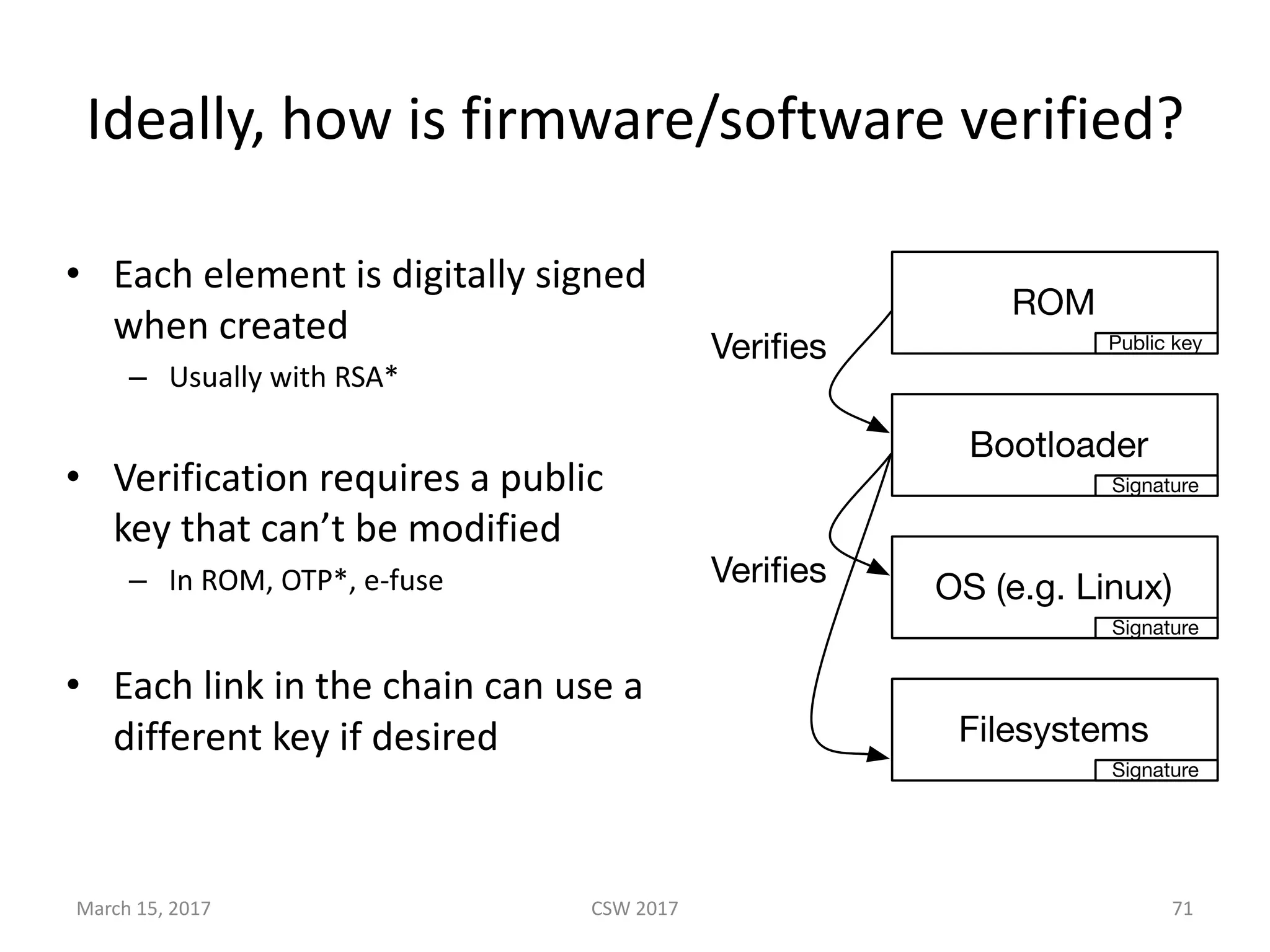

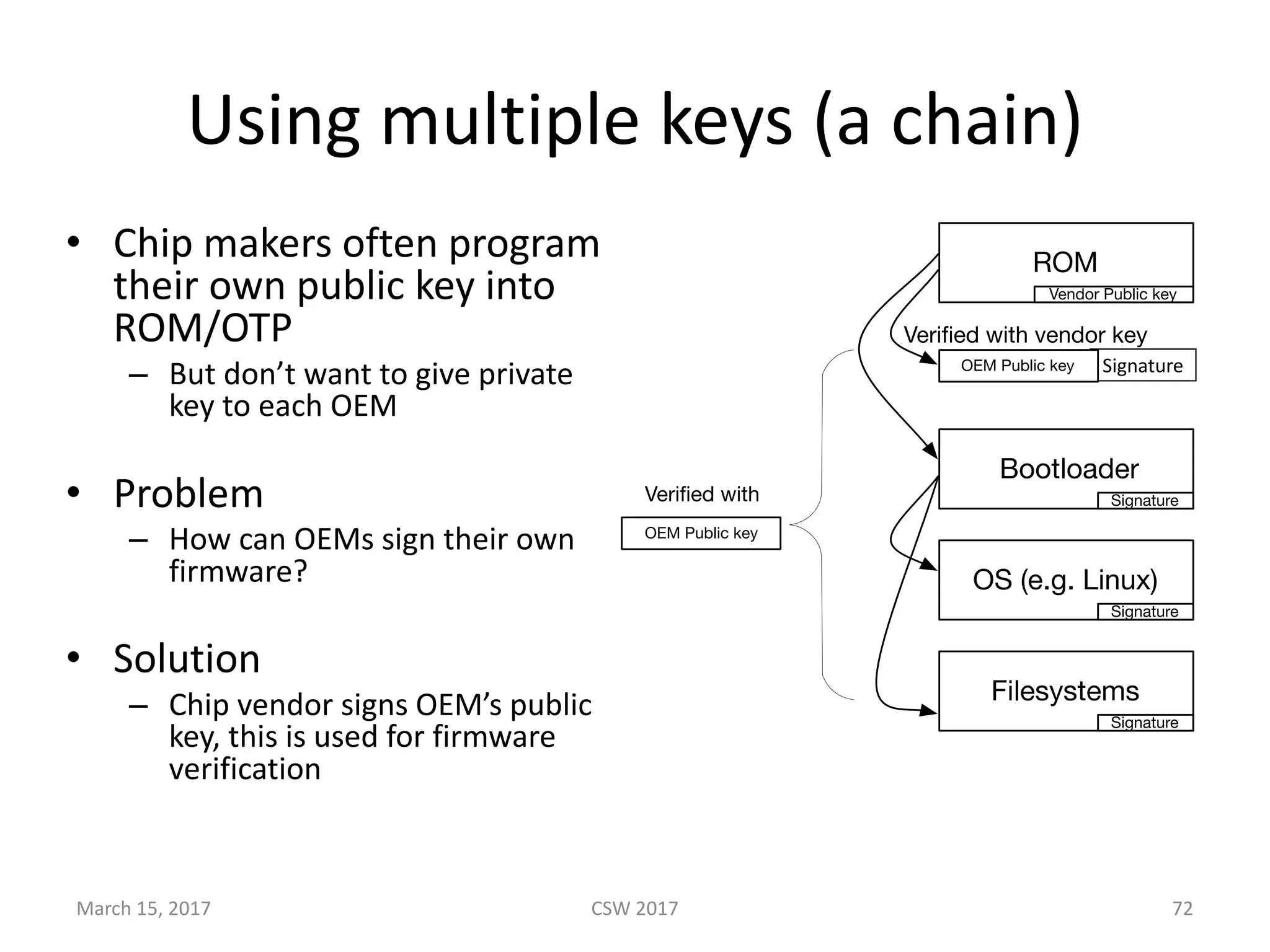

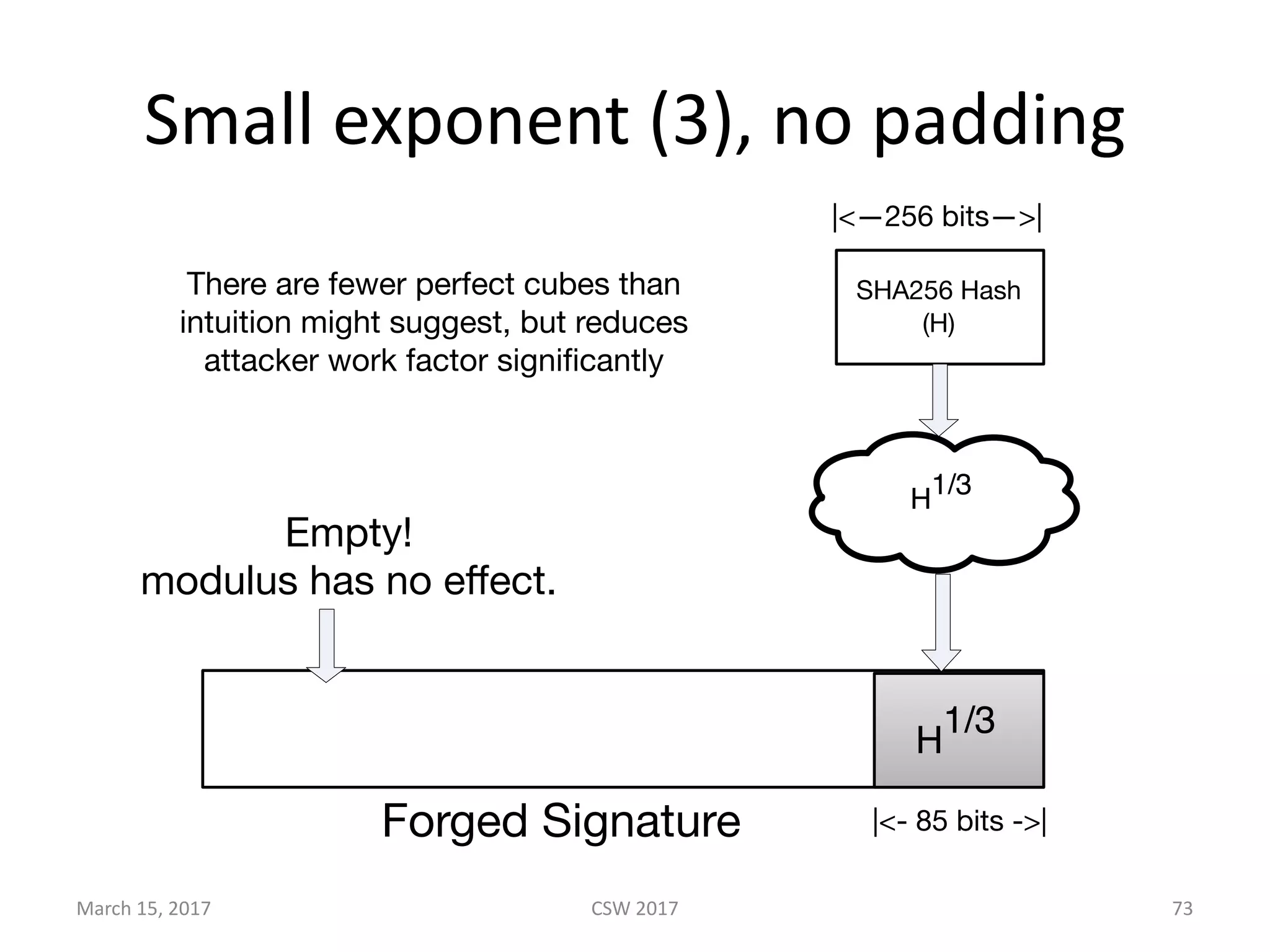

This document summarizes Scott G. Kelly's presentation on secure boot flaws in IoT and embedded systems. Kelly discusses how secure boot is intended to work by only allowing authorized firmware to run, but that many systems implement it incorrectly. Common flaws include using symmetric keys that can be extracted from devices, having an "optional" secure boot that can be easily disabled, and having a weak root of trust if the first code executed is stored in unprotected flash. Kelly urges vendors to properly implement secure boot to prevent malware from replacing firmware and compromising systems.