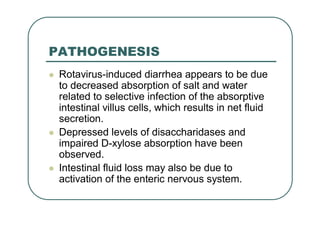

Rotaviruses are the most common cause of severe diarrhea in infants and young children worldwide. They contain 11 segments of double-stranded RNA and belong to the Reoviridae family. Nearly all children are infected by rotavirus by age 5. While first infections after 3 months of age are usually symptomatic, subsequent infections tend to be milder. Treatment focuses on rehydration and prevention of dehydration. Vaccines provide the most effective prevention.