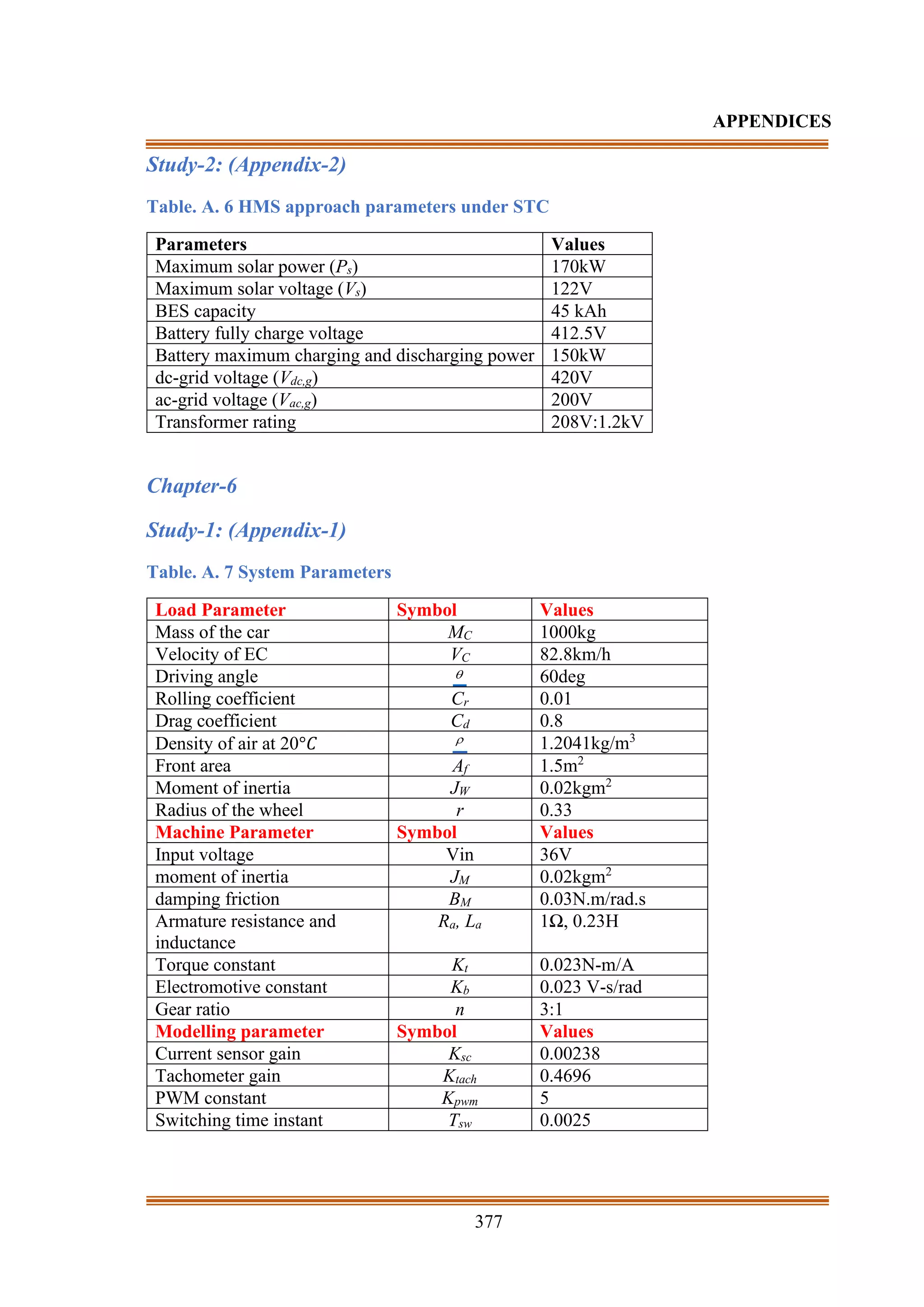

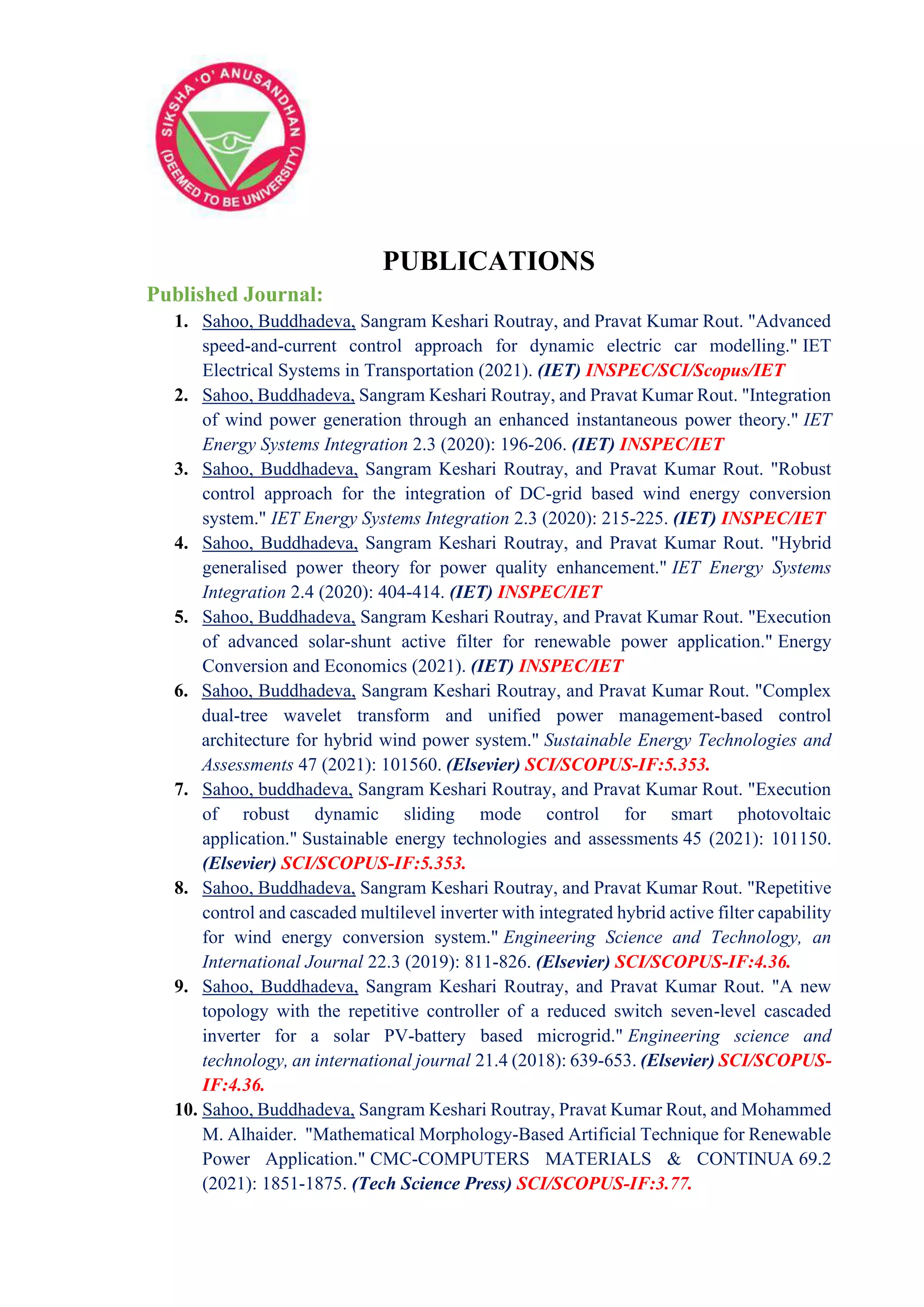

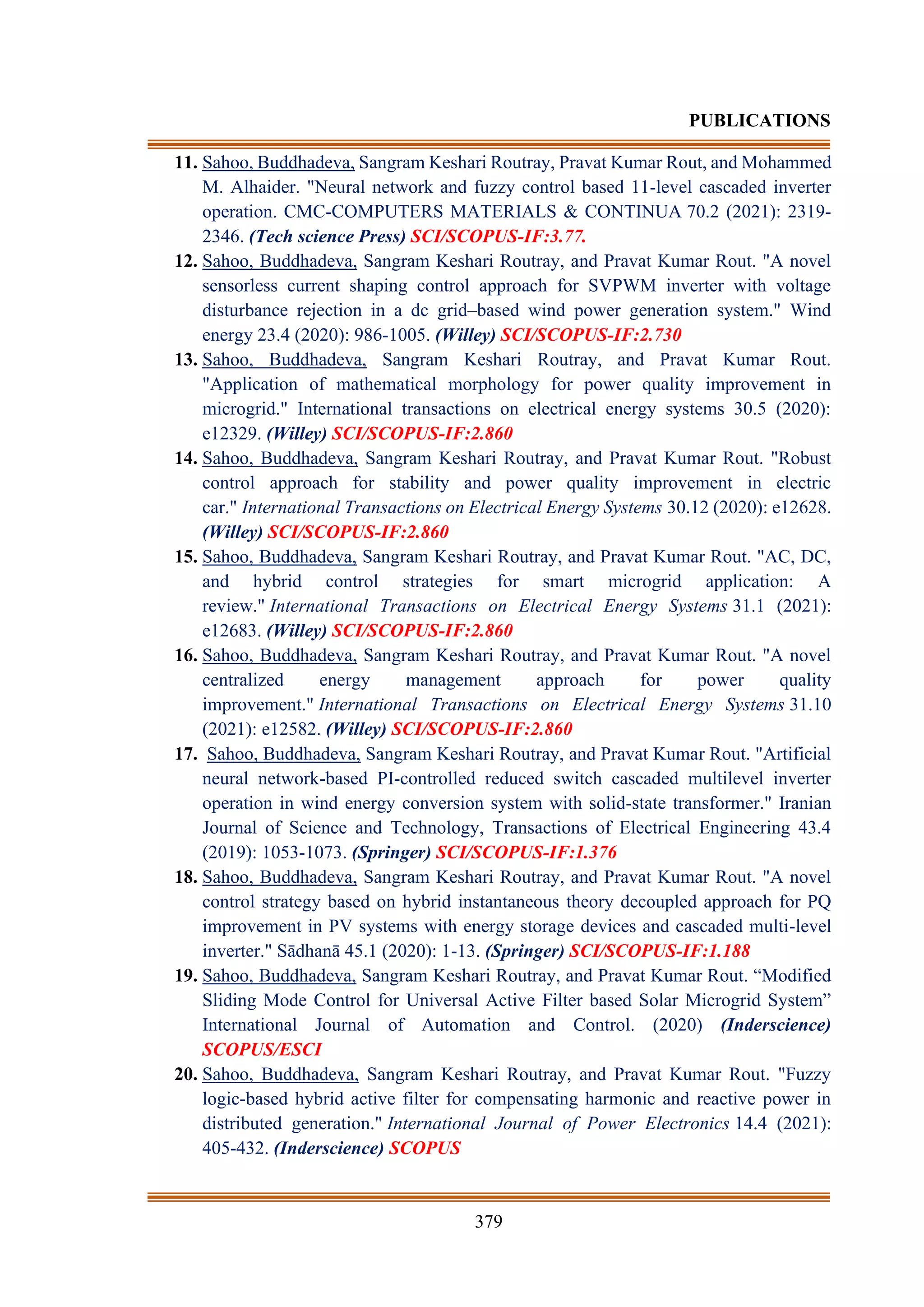

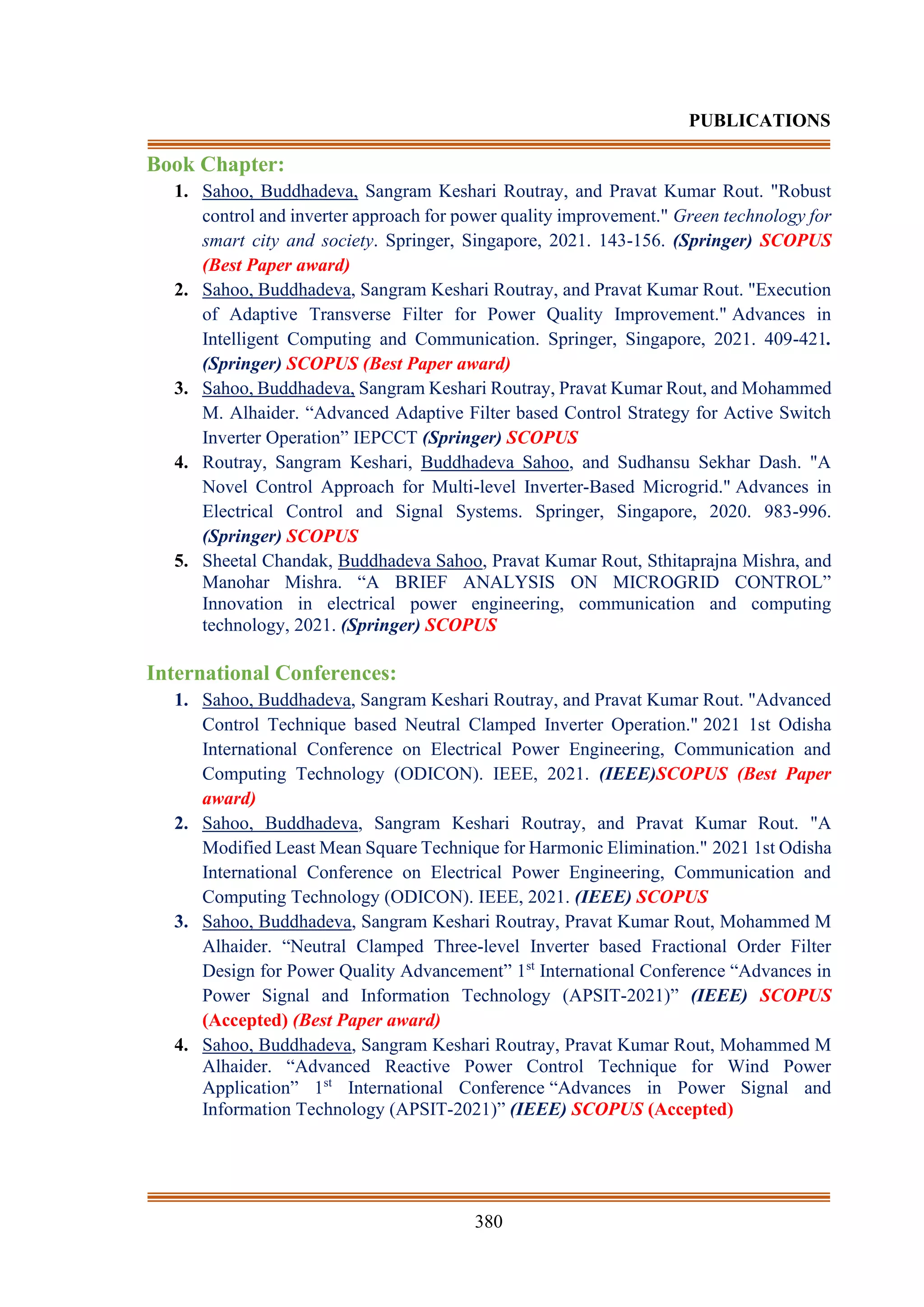

The document discusses hybrid microgrid applications involving renewable energy sources like solar and wind. It notes that the variable output from these sources can cause power quality issues in hybrid microgrids. Two studies are proposed to address this: 1) A robust control approach is proposed to integrate a DC-grid based wind energy conversion system to improve reliability. 2) A novel centralized energy management approach is suggested to suppress voltage variations and improve power quality, using a battery energy storage system. The document also reviews various multilevel inverter topologies used for renewable energy integration and highlights the need for improved topologies to balance capacitor voltages and minimize harmonics.

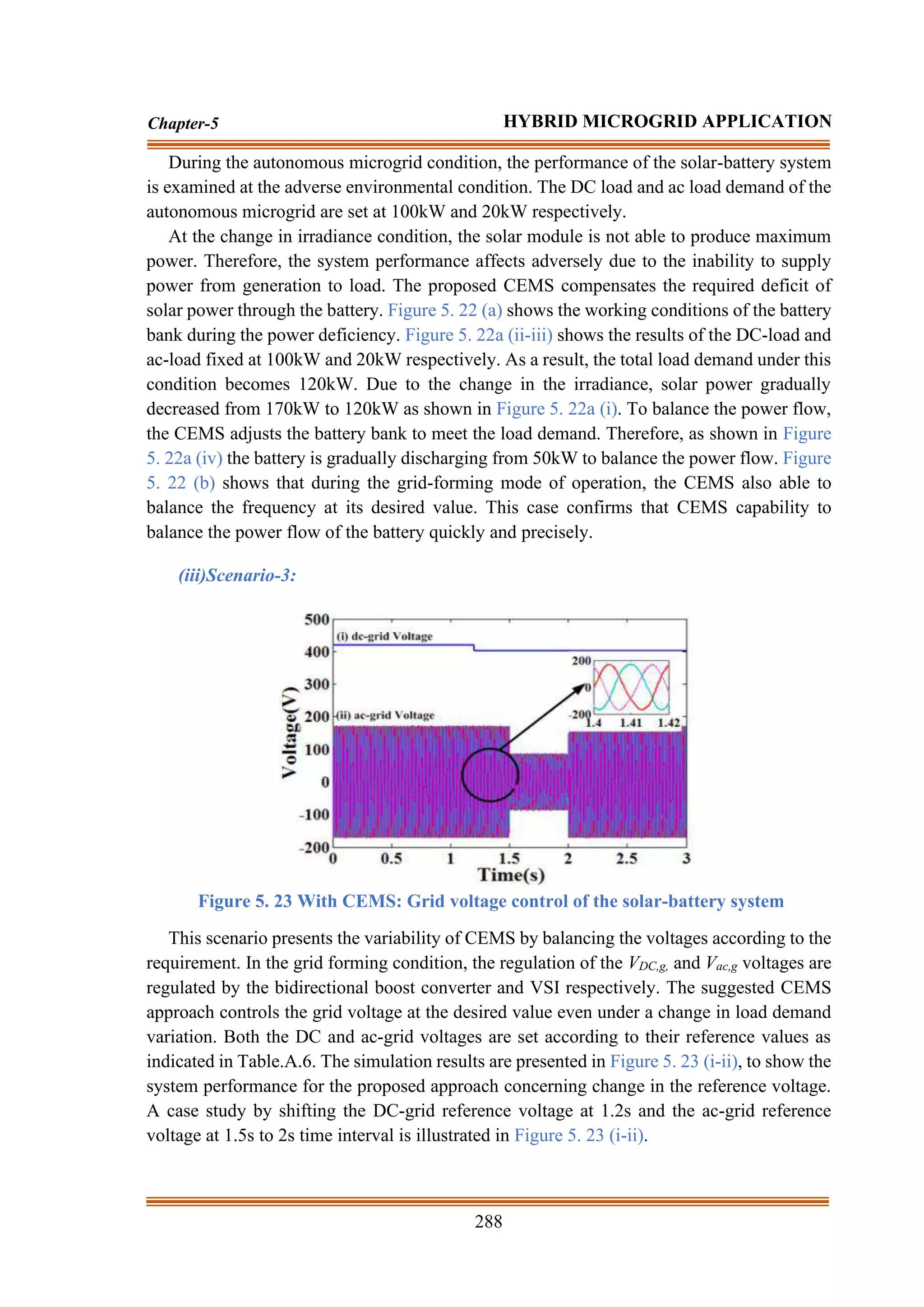

![Chapter-5

HYBRID MICROGRID APPLICATION

5.1 Introduction

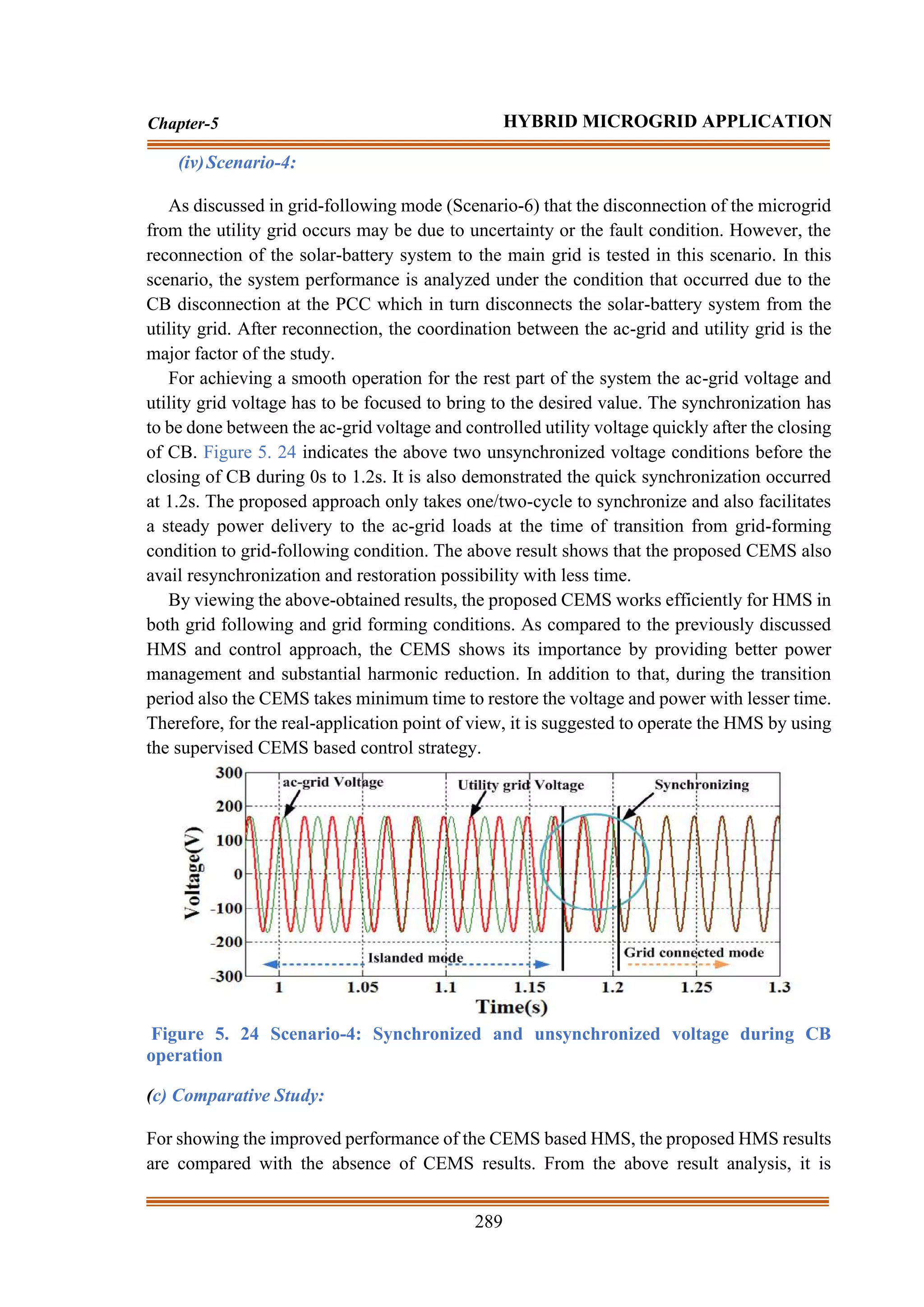

High energy demand and increased population conditions motivate many electrical power

experts to get different sustainable solutions for an appropriate amount of energy production

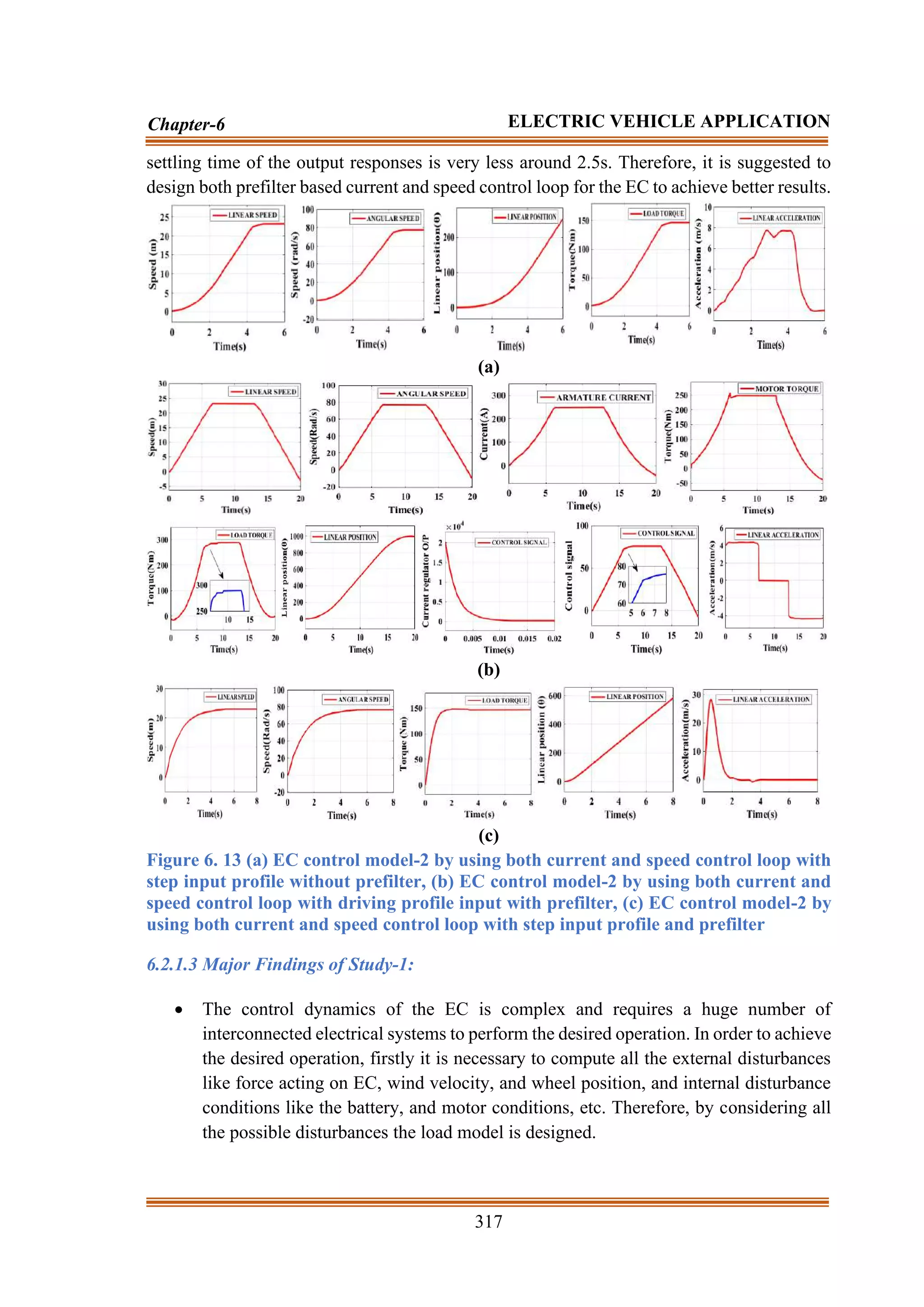

by reducing the dependency on traditional energy production [154]. To regulate the PQ and

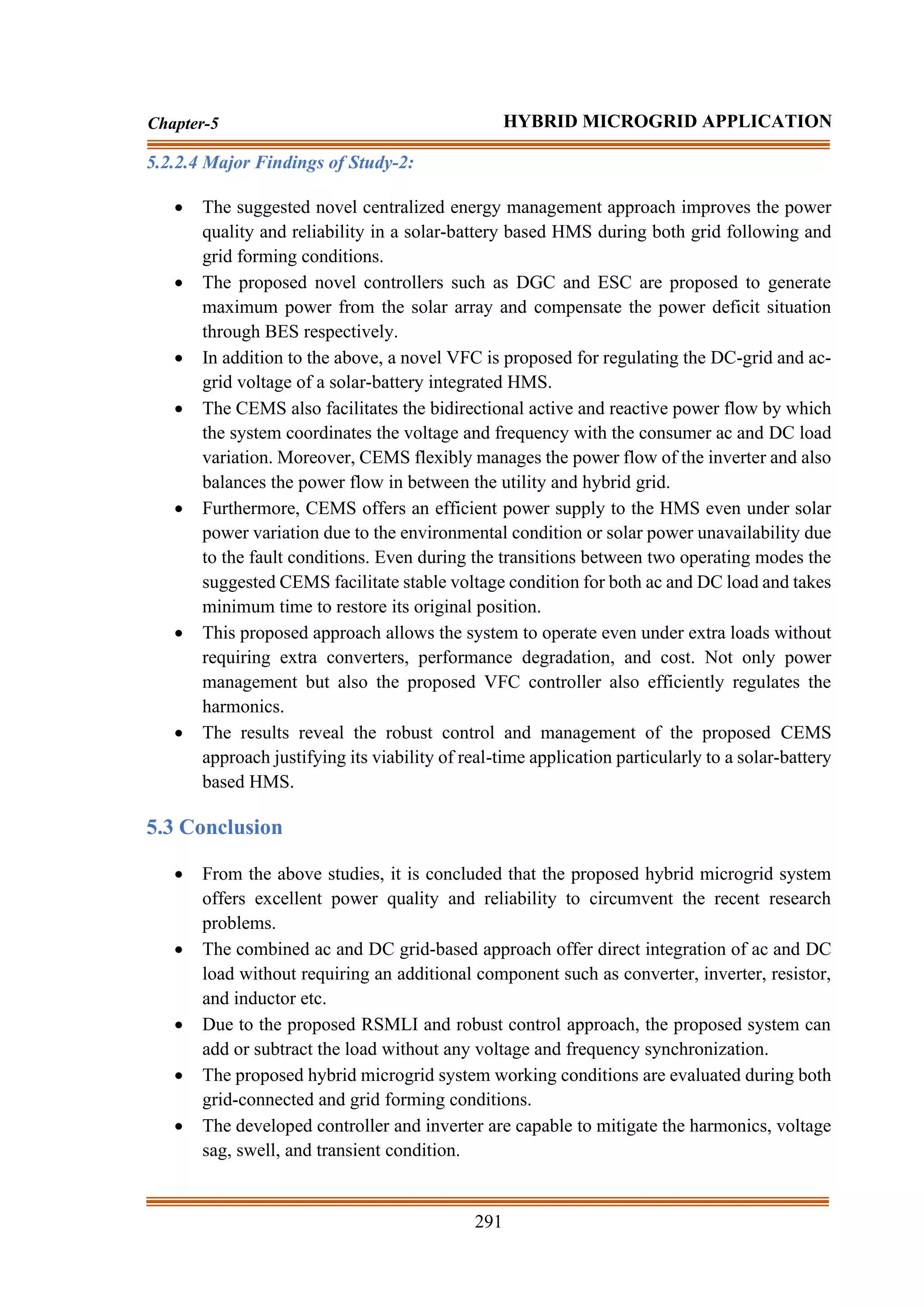

power reliability, solar array and wind energy-based distributed generators (DGs) are

prominent because of their smart characteristics such as availability, technological growth,

reduced installation cost, and environment-friendly nature [289]. However, the output results

of the hybrid microgrid systems (HMSs) are distorted due to the varying in atmospheric

conditions such as irradiance and temperature, and wind speed conditions [212]. Therefore,

to extract optimum power from the solar array and wind energy-based HMS, it is necessary

to emphasize the appropriate selection of the maximum power tracking (MPT) method.

Further, to suppress the voltage sag and swell conditions during the transient conditions, a

novel BES device-based energy management control technique is also required for HMS

operation.

Due to the advanced power electronic devices, BES, and infiltration of DC distributed

generations (DGs) like photovoltaic cells and fuel cells, the research is gaining interest in

DC-grid based systems. Many similar DC-grid based research outcomes are presented in

[290]. A novel design for a DC-grid based WECS is presented by comprised with a matrix

converter, high-frequency transformer and a single-phase ac/DC converter in [290-291].

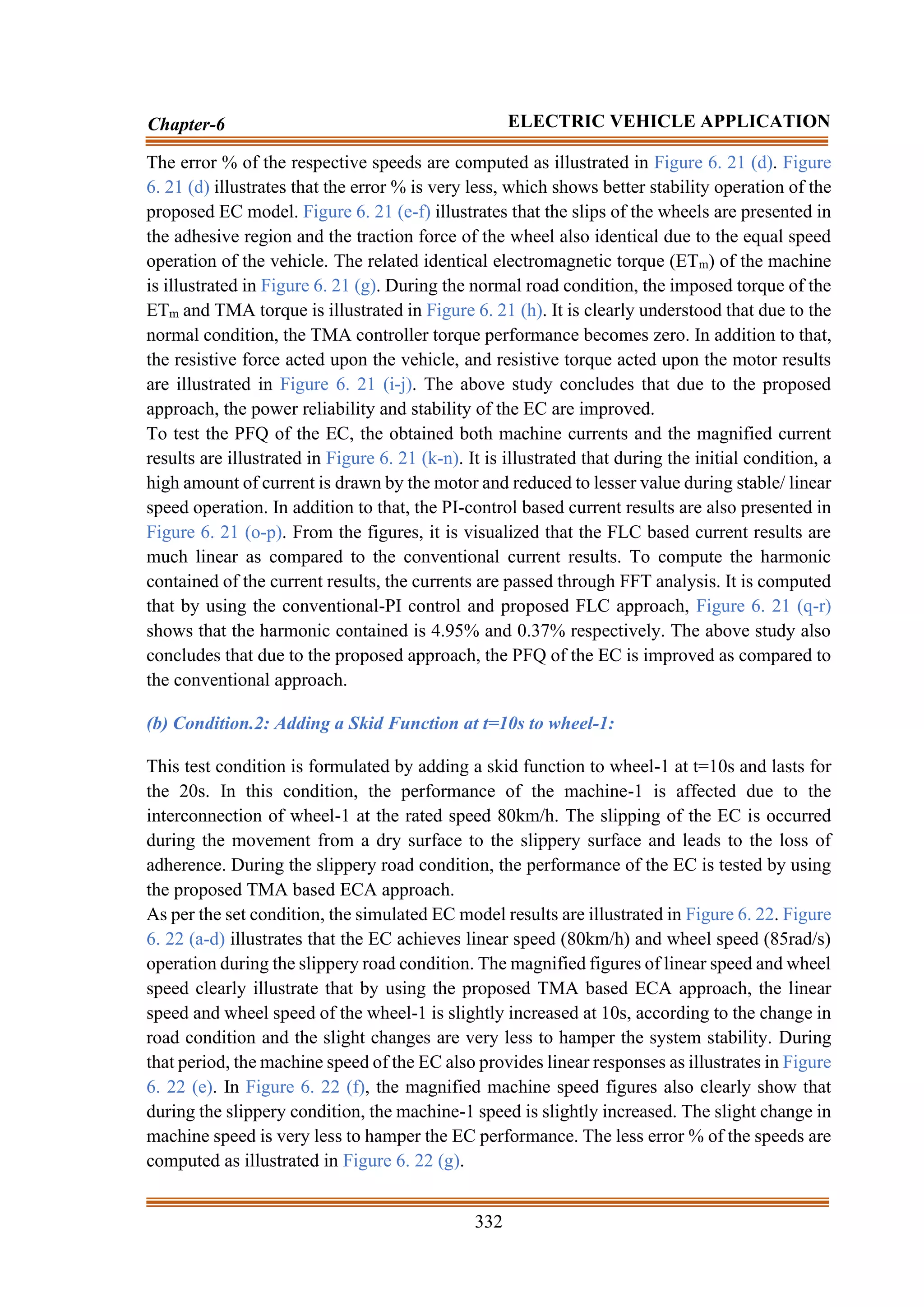

However, for three-phase applications, the system complexity is increased exponentially

along with the cost. In [292], a DC-grid based wind farm is proposed with a cluster of four

WTs as a group and making each group attached to a converter for grid integration. However,

the sudden shutdown of one converter affects all the WTs performances and the system loses

its voltage and frequency synchronization. In [94,293-294], a hybrid ac-DC grid WECS is

suggested with both ac and DC networks attached by a bidirectional converter for similar

applications. Various hierarchical algorithms are implemented for the smoother power

transfer between ac and DC microgrid. However, the stoppage of one bidirectional converter

operation leads to the disconnection between ac and DC microgrid. Therefore, there is a

requirement for further study by which the ac output of WTs in a poultry farm is connected

to a common voltage at the DC-grid based microgrid for smooth and reliable operation.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dr-211204045233/75/Robust-Active-Power-Filter-Controller-Design-for-Microgrid-and-Electric-Vehicle-Applications-part-2-35-2048.jpg)

![241

Chapter-5 HYBRID MICROGRID APPLICATION

Multilevel inverter (MLI) plays a significant role in the case of high power and DG

applications. MLI facilitates sinusoidal output voltage with reduced harmonics, better

voltage regulation, and better power quality, mainly for its wider output voltage levels [295-

296]. Particularly to BES based on DG integration with the grid through MLIs; a lot of

research is devoted in recent times. In [297], the integration of multiple isolated DC-sources

by using a cascaded H-bridge inverter is proposed for generating a wider voltage level with

plasma stabilization. The issues regarding the integration of multiple rectifiers and balancing

the capacitor voltage are analyzed in [298]. A detailed study is presented in [15] for a wider

range of voltage levels and the load current switched through the capacitors. In this case, the

capacitor voltages are balanced to a required value by adjusting the path of load current

through the capacitor by choosing the redundant states for equal pole voltage. By combining

the concepts of [297] and [223], a floating cascaded inverter is presented in [299]. In [300],

the idea of cascading FCI with a neutral clamped inverter (NCI) is presented. Later it is

shown that the FCI generates more voltage levels by using the different combinations of

capacitors and switches [301-302]. However, in [301-302] the voltages of the capacitors are

not balanced instantaneously and the voltages are stable only for the fundamental

frequencies. Considering the above-related issues this study attempts with an objective to

design an HCMLI for distributed microgrid systems.

Recently, many power engineers have suggested different sustainable solutions for

designing an appropriate power management control (PMC) technique for HMS operation,

and among those literature few prominent techniques are discussed as follows. In [303], a

PMC approach is suggested for achieving a stable voltage and frequency operation in the

hybrid wind-solar battery system. However, the PMC approach is proposed for only single-

phase applications and also not focused on the reactive power support provision essential for

voltage regulation. In [304], for the similar hybrid wind-solar battery system, a different

PMC approach is suggested for optimizing the cost and size of the solar array and BES

without focusing the voltage and frequency stabilization. However, this technique has a

major limitation of requiring large historical data of the past 30 years to compute the power

production capability of wind and solar systems. In [223], as an improvement to [304], a

novel optimization technique is suggested for the wind-solar battery system. However, both

[304] and [223] give more emphasis on the size and cost estimation rather than the optimal

control strategy for better power regulation and synchronization with the grid. A novel PMC

technique based on the droop control strategy is suggested for availing better load sharing

operation between a similar solar-battery unit and other load stations [305]. In [306], as an

improvement to [305], a modified control technique is proposed by using different generating

power units. Though [305-306] successfully supplies the power demand with an improved

power regulation in the grid-forming mode of operation but fails to emphasize on the energy

supervision factor among the generation and load. Moreover, the above approaches are also

not considered DC-grid and load. Ref [307] suggests a supervised control strategy for the

hybrid solar-battery-hydropower system, in which the ac-grid voltage is regulated through

hydropower unit, and active and reactive power demand is fulfilled through solar-battery unit

respectively. A similar control strategy is also suggested for the solar-battery-diesel system](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dr-211204045233/75/Robust-Active-Power-Filter-Controller-Design-for-Microgrid-and-Electric-Vehicle-Applications-part-2-36-2048.jpg)

![242

Chapter-5 HYBRID MICROGRID APPLICATION

[287]. However, in both [307, 287], the control technique is silent about the voltage and

frequency control during the failure of the hydro/diesel power. During an autonomous solar

system, a distributed control approach for the above issues is studied during grid forming

mode conditions [308]. The above method is used to solve the load sharing problem with

multiple generators and battery stations. Similarly, in [309], a modified approach is used to

regulate the single-phase low voltage microgrid application during grid forming conditions.

None of the above-discussed proposals are considered the hybrid grid (ac/DC) conditions for

power-sharing between the ac/DC grid and the main grid. In [310], a centralized approach

based on one-day forecasting data is suggested for a grid following HMS. The integration of

the solar and battery to the ac-grid through a decentralized VSI is dissimilar from the

undertaken system arrangement in this study. An attempt based on dynamic controller and

ANN technique has been made in [310-312] for appropriate power prediction of the DGs and

better power management. In [313], for a similar solar-battery based system, low pass filter

(LPF) or high pass filter (HPF) and bandpass filter (BPF) devices are used to decrease the

lower order harmonics and extracts the fundamental component. However, as per the real-

application point of view, these solutions are not promising solutions to offer faster dynamic

and smoother filtering conditions. For better power regulation and quality, a novel inverter-

based technique is discussed with the traditional control techniques [314]. In [286-315], a

robust current shaping technique is suggested to offer optimum power regulation and power

quality in a hybrid microgrid system. However, the proposed approach fails to provide a

better energy management system looking at the SOC of the battery condition. In addition to

that, the proposed approach does not consider the effects of environmental change

conditions. In [316], optimal planning and design of HMS are used to compute the real power

losses during the weekday and weekend requirements. However, the proposed hybrid system

does not consider the DC-grid and the power transfer capability of the system. Due to the

absence of DC-grid, the direct connection of DC-load is impossible. With a motivation to

result in better power regulation and quality, by considering the above limitations for an

HMS, this study is extended further to design an appropriate centralized coordinated control

technique for better power management in both grid following and grid forming mode of

operation.

Therefore, this chapter is divided into three individual studies as study-1, and study-2, by

focusing on the main aim of RSMLI design and its control strategy through a robust

controller. By using the developed RSMLI and its control strategy, the RES-based hybrid

microgrid system is designed and its performances are also studied at different state

conditions. To test the performance of the designed parameters like inverter and robust

controller, HMSs are the best test systems during non-linear load applications. The main

contribution to the individual studies is presented as follows.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dr-211204045233/75/Robust-Active-Power-Filter-Controller-Design-for-Microgrid-and-Electric-Vehicle-Applications-part-2-37-2048.jpg)

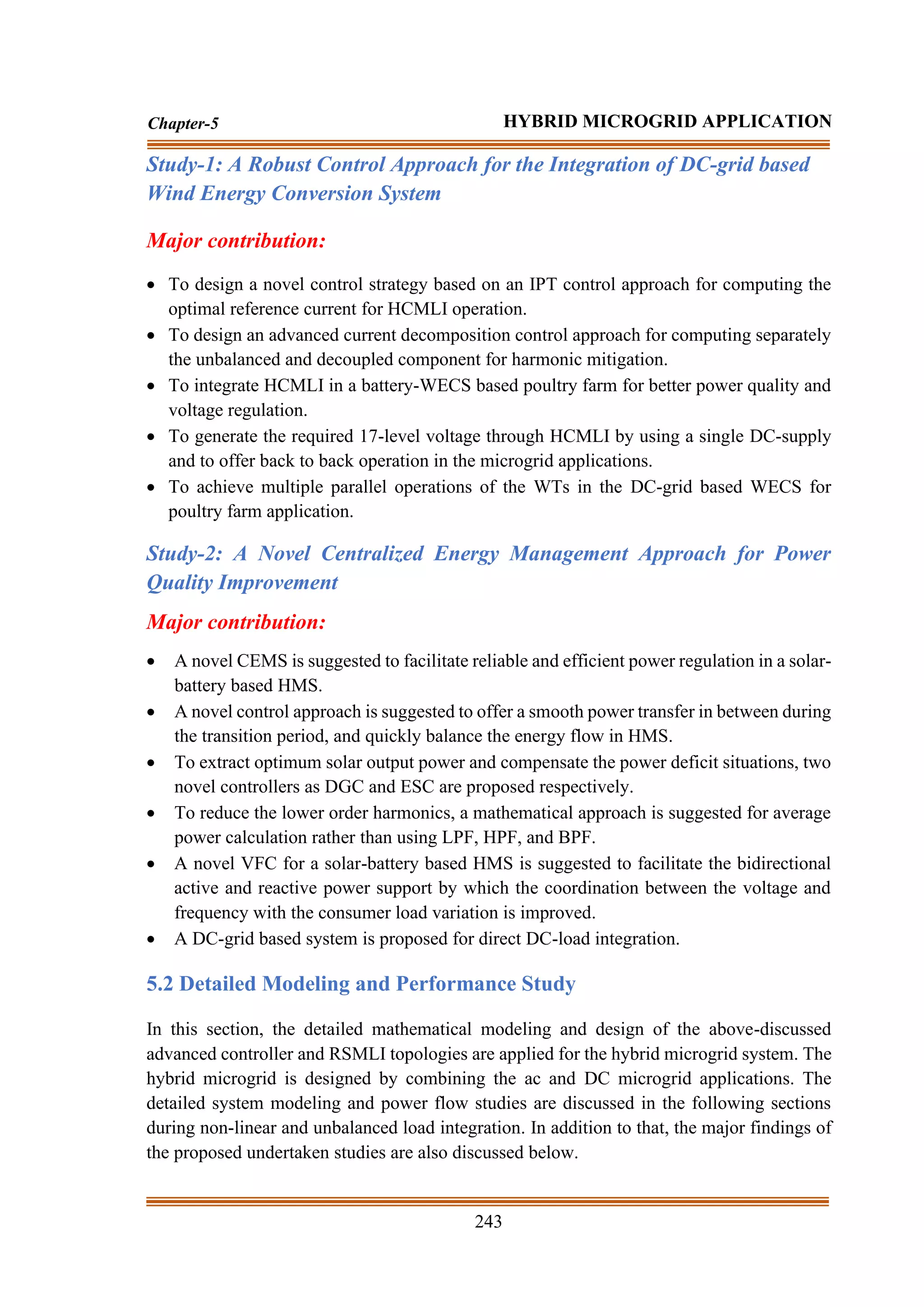

![245

Chapter-5 HYBRID MICROGRID APPLICATION

turbines (WTs), four three-phase ac-DC voltage source converters connected to each of the

PMSG outputs (converters 1, 2, 3, and 4), and two HCMLI (HCMLI-1, and HCMLI-2)

having the maximum 20kW capability each. A PMSG based WECS is chosen considering

the less cost factor, easy real-time implementation, and simple control structure due to the

absence of any DC excitation system. Proposed WECS decreases the requirements of

numerous inverters at the generating stations. The coordination of the power electronic

devices is monitored by the centralized energy management system (CEMS). Through a

centralized server, the CEMS checks and monitors the generation of wind power and

consumption of load power. CEMS also monitors and regulates both the inverter voltages to

an equal desired value for preventing excess circulating currents in between them. In addition

to that, CEMS is also responsible for other aspects of power management like unit

commitment, load forecasting, economic load dispatch, and better power quality, etc.

All key data like measuring the total area of the installation system by using smart meters,

tap positions of the transformers, and the movements of the circuit breakers (CBs) are sent

to the CEMS by using wire-line or wireless communications. The maximum wind power

(Popt,w) from each of the WTs is obtained as follows[212].

3

r

,

opt

opt

w

,

opt )

(

*

K

P

= (5.1)

3

opt

opt

,

P

opt )

R

(

A

C

2

1

K

= (5.2)

R

v

*

opt

r

,

opt

= (5.3)

where ‘Kopt’ is the optimum constant parameters, ‘ r

,

opt

’ is the optimum speed of the WT,

‘ opt

,

P

C ’ is the optimum turbine power coefficient, ‘ ’ is the density of air, ‘A’ is the swept

area of the rotor blade, ‘ opt

’ is the optimized tip speed ratio, ‘v’ is the speed of the wind,

and ‘R’ is the radius of the blade.

As shown in Fig.1 for the islanding mode of operation (IMO), a BES is integrated with

the WECS. The size of the battery is chosen as 80 Ah and linked with the DC-grid through

a 40kW bidirectional buck-boost converter [273]. The battery charging and discharging

operational mode is achieved during the grid-connected and islanded mode of operation

respectively. The energy constraint of the storage device is calculated based on state-of-

charge (SOC) limits and represented as:

SOCmin<SOC<SOCmax (5.4)

As presented in [317] and [274], the SOC of the BES is calculated through an estimation

method. During the fewer load demand, the battery will be charged by using the surplus

charge of the WTs and at high load demand or islanding conditions, the power is transmitted

from the battery.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dr-211204045233/75/Robust-Active-Power-Filter-Controller-Design-for-Microgrid-and-Electric-Vehicle-Applications-part-2-40-2048.jpg)

![246

Chapter-5 HYBRID MICROGRID APPLICATION

(b)Operation of the System:

During the grid-connected mode of operation (GMO), the WTs are responsible for

supplying the generated power to the loads without giving an extra burden to the distribution

grid. BES can be controlled to attain the load side requirement depending on the time of use

of electricity and the SOC of the battery [278-279].

During the islanded mode of operation (IMO), the CB is used to detach the microgrid

from the grid. In this case, the WTs and battery are the only existing sources to fulfill the

load demand. To balance the power, the battery is used to supply the deficit of active power

into the system. The power balance equations are represented as:

PWTs + Pbat = PL, syst + PL (5.5)

where PWTs is the active power of the WT. Pbat is the battery active power which is subjected

to the constraints of the battery maximum power (Pbat,max) that can be distributed at the

discharging mode of operation (Pbat<Pbat,max ). PL,syst and PL denote the power loss, and load

power respectively.

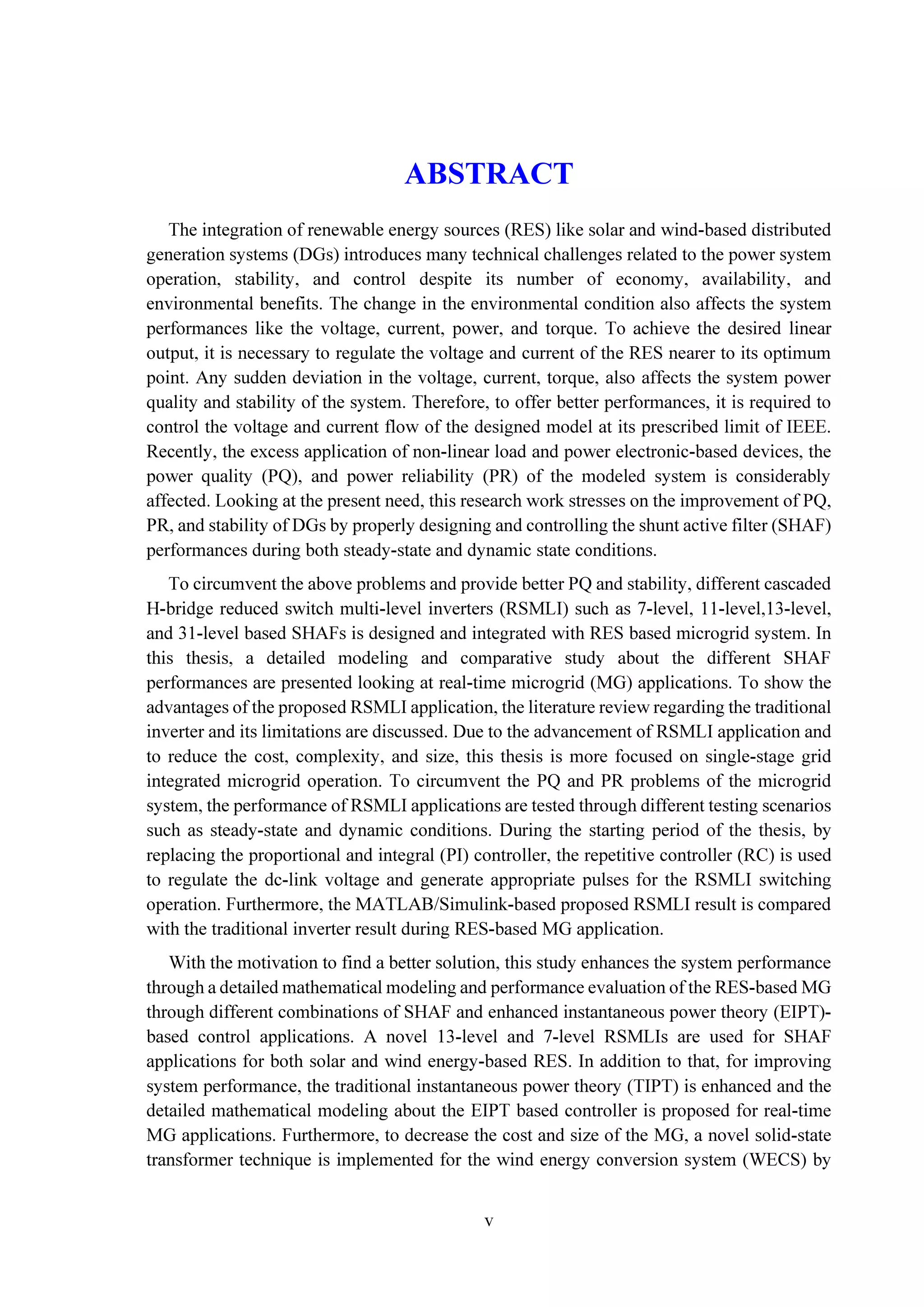

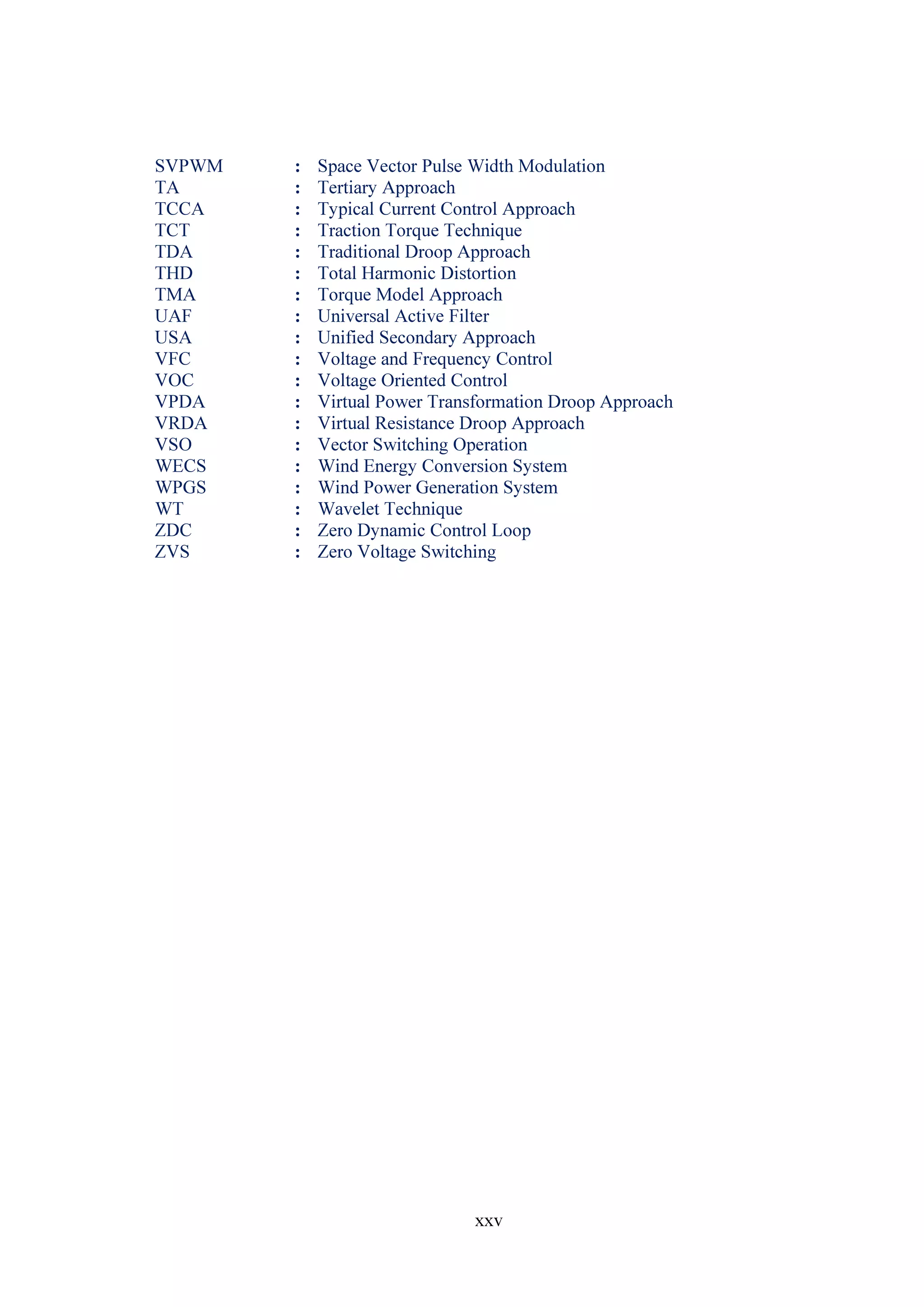

(c) Proposed HCMLI Topology:

SA1 SA2 SA3 SA4 SA5 SA6 SA7 SA8

SA1` SA2` SA3` SA4` SA5` SA6` SA7` SA8`

SB1 SB2 SB3 SB4 SB5 SB6 SB7 SB8

SB1` SB2` SB3` SB4` SB5` SB6` SB7` SB8`

SC1 SC2 SC3 SC4 SC5 SC6 SC7 SC8

SC1` SC2` SC3` SC4` SC5` SC6` SC7` SC8`

AC1 AC2 AC3 AC4

BC1 BC2 BC3 BC4

CC1 CC2 CC3 CC4

2

/

Vdc

2

/

Vdc

2

/

Vdc

4

/

Vdc

4

/

Vdc

4

/

Vdc

8

/

Vdc 16

/

Vdc

8

/

Vdc

8

/

Vdc

16

/

Vdc

16

/

Vdc

Lf

dc

V

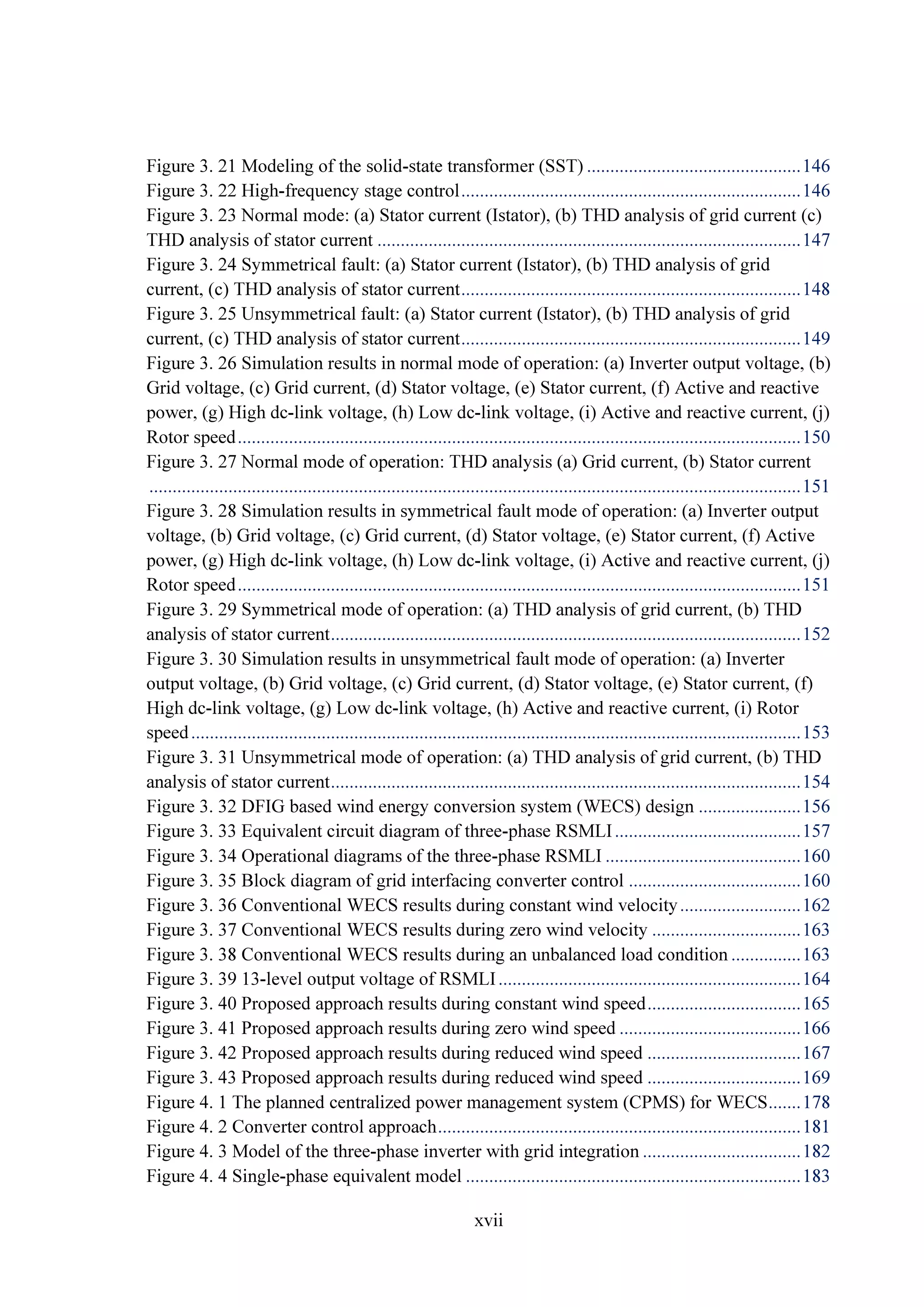

Figure 5. 2 Schematic diagram of proposed HCMLI

The proposed HCMLI is designed with cascading a 3-level FCI and three floating

capacitor H-bridges. The 3-phase17-level HCMLI schematic diagram is illustrated in Figure

5. 2. As shown in Figure 5. 2, phase-A contains the switch pairs as [( 1

SA ,

1

SA ), ( 2

SA ,

2

SA ),

( 3

SA ,

3

SA ), ( 4

SA ,

4

SA ), ( 5

SA ,

5

SA ), ( 6

SA ,

6

SA ), ( 7

SA ,

7

SA ) and ( 8

SA ,

8

SA )], phase-B

contains the switch pairs as [( 1

SB ,

1

SB ), ( 2

SB ,

2

SB ), ( 3

SB ,

3

SB ), ( 4

SB ,

4

SB ), ( 5

SB ,

5

SB ), ( 6

SB ,

6

SB ), ( 7

SB ,

7

SB ) and ( 8

SB ,

8

SB )], and phase-C contains the switch pairs 9 as [( 1

SC ,

1

SC ), ( 2

SC ,](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dr-211204045233/75/Robust-Active-Power-Filter-Controller-Design-for-Microgrid-and-Electric-Vehicle-Applications-part-2-41-2048.jpg)

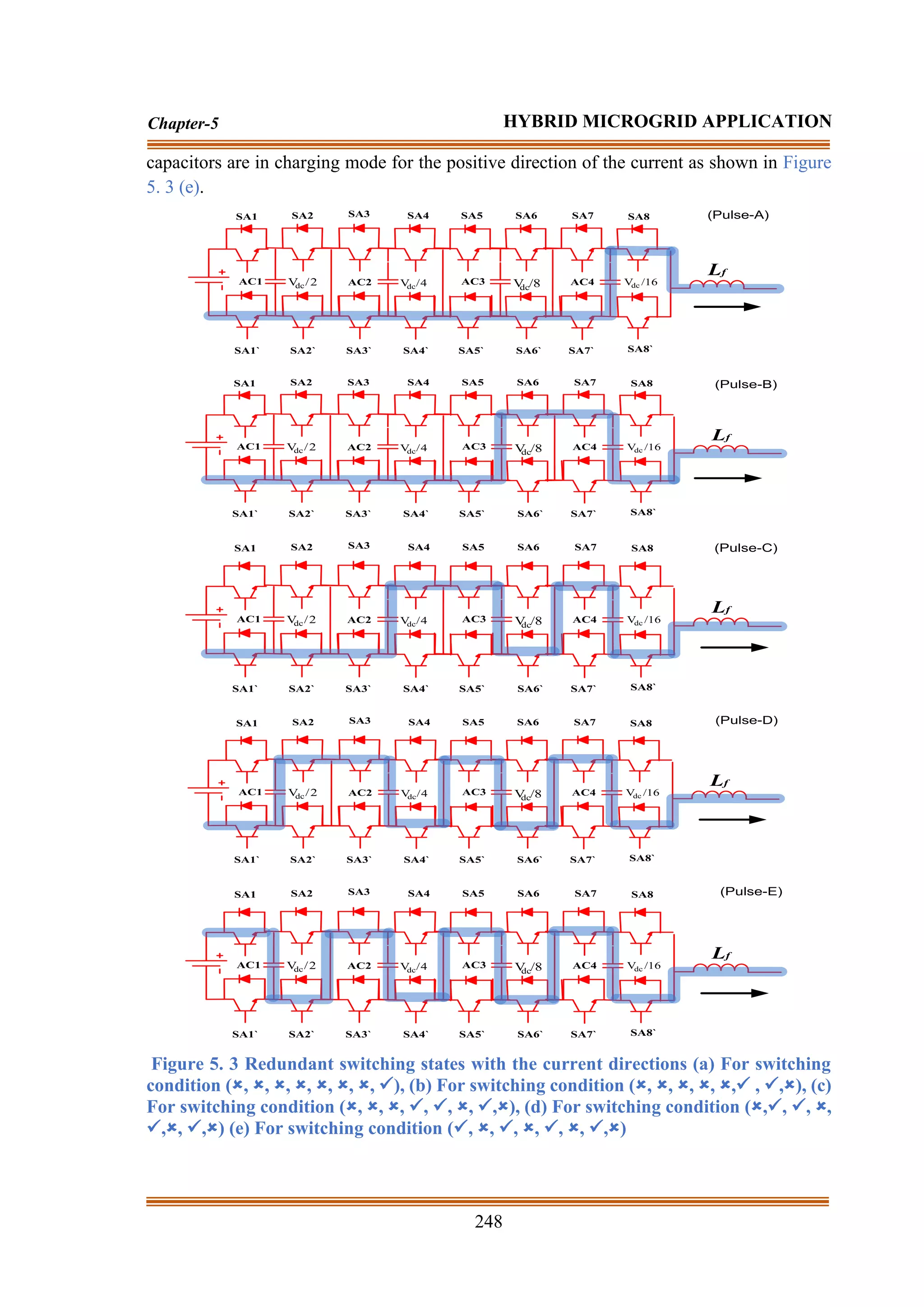

![247

Chapter-5 HYBRID MICROGRID APPLICATION

2

SC ), ( 3

SC ,

3

SC ), ( 4

SC ,

4

SC ), ( 5

SC ,

5

SC ), ( 6

SC ,

6

SC ), ( 7

SC ,

7

SC ) and ( 8

SC ,

8

SC )] respectively.

The proposed hybrid inverter contains four capacitors in each phase like ( 1

AC , 2

AC , 3

AC , and

4

AC ), ( 1

BC , 2

BC , 3

BC , and 4

BC ), and ( 1

CC , 2

CC , 3

CC , and 4

CC ) respectively. As indicated in

Figure 5. 2, the pole voltages of the capacitors 1

AC , 1

BC , and 1

CC are fixed at the voltage level

of VDC/2, capacitors 2

AC , 2

BC , and 2

CC are fixed at the voltage level of VDC/4, capacitors 3

AC ,

3

BC , and 3

CC are fixed at the voltage level of VDC/8, and capacitors 4

AC , 4

BC , and 4

CC are

fixed at the voltage level of VDC/16 respectively.

In this topology, each of the cascaded H-bridges (CHBs) voltages can be added or

subtracted to the voltage of the previous stage. HCMLI voltage levels are determined by

adding the voltages of each stage of the inverter. Each pair of the switch contains two

different logic states as the top device are ON (indicated as ‘✓’) and the bottom device is

OFF (indicated as ‘’). For the above switching states, there are 256 (28

) switching

combinations are possible for the inverter operation. The voltage levels of HCMLI can be

determined by using one or more switching combinations (pole voltage redundancies). In the

case of the same pole voltages, by using the redundant switching combinations, the

capacitor’s current can be changed and the voltages of the capacitors can be controlled to

their set values. By using the above combinations, the balanced capacitor voltages at all load

currents and power factors instantly have been studied for 17 voltage levels. The voltage

levels are 0, VDC/16, 2VDC/16, 3VDC/16, 4VDC/16, 5VDC/16, 6VDC/16, 7VDC/16, 8VDC/16,

9VDC/16, 10VDC/16, 11VDC/16, 12VDC/16, 13VDC/16, 14VDC/16, 15VDC/16, and VDC.

The HCMLI generates the 17-level output voltage by using 82 switching arrangements

as indicated in Chapter-5 Appendix-1 (Table.A.5). For positive current, the effect of 82

switching arrangements on every capacitor charging and discharging conditions (during that

period the pole is the source current as indicated in Figure 5. 3) is illustrated in the Chapter-

5 Appendix-1 (Table.A.5). For the negative current, the switching arrangements on the

capacitors are changed accordingly. For example, while the controller needs a pole voltage

of VDC/16, in HCMLI five unlike redundant switching arrangements are possible as indicated

in Figure 5. 3. Each switching arrangement has a different outcome on the state charge of the

capacitors. In Figure 5. 3 (a), at (, , , , , , , ✓) switching state (as shown in

Table.A.5), the capacitor C4 is at discharging mode. To balance the C4 voltage and to fetch

the voltage at its set value (VDC/16), one of the other four switching arrangements is selected

as shown in Figure 5. 3 (b-e). As shown in Figure 5. 3 (b), for (, , , , , ✓, ✓, )

switching state, the current direction of C4 is reversed and the capacitor C4 is charged.

However, due to the above switching state, the capacitor C3 is discharged. As illustrated in

Figure 5. 3 (c), to charge C3 and to balance the pole voltage, the switching redundancy (,

, , ✓, ✓, , ✓,) is chosen. Similarly, due to the charging of C3, C2 is discharged. Based

on the C1 charging condition, to charge C2 one of the switching arrangements is chosen

between Figure 5. 3 (d) and Figure 5. 3 (e). If the switching arrangement is (,✓, ✓, , ✓,,

✓,), the C1 is in the discharging mode and the state of charge of all other capacitors is shown

in Figure 5. 3 (d). Finally, for the switching combinations (✓,,✓, , ✓, , ✓,), all the](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dr-211204045233/75/Robust-Active-Power-Filter-Controller-Design-for-Microgrid-and-Electric-Vehicle-Applications-part-2-42-2048.jpg)

![250

Chapter-5 HYBRID MICROGRID APPLICATION

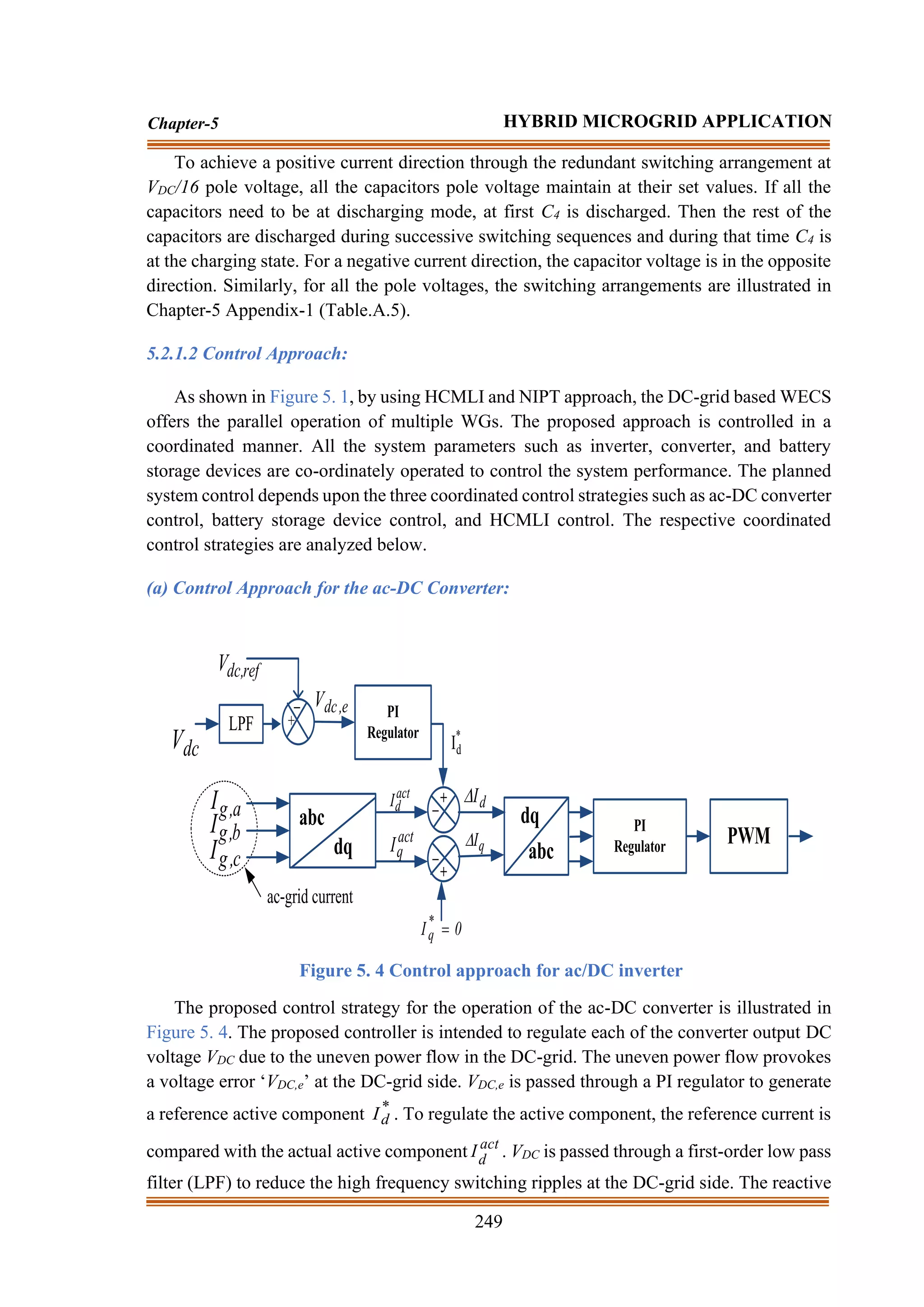

current is controlled to be zero by which the PMSG can deliver only active power. By

analyzing the reference and the actual values of current, the current error signal d

I

and q

I

are computed. Then by using the dq-abc transformation, the corresponding error signal is

given as input to the repetitive controller to produce the appropriate pulse width modulation

(PWM) signal [154]. Due to the use of a constant wind speed ventilation fan, the wind speed

is constant all the time. Therefore, the proposed ac-DC converter approach easily eliminates

the need of maximum power point (MPP) strategies for the regulation of speed and

electromagnetic torque of the wind turbine. Due to the elimination of MPP strategies, the ac-

DC converter control strategies become simpler and reduce the computational burden easily.

(b) Control Approach for Battery Energy Storage (BES) Device:

*

bat

P

bat

P

+

-

+

-

demand

,

g

P

*

g

P

*

g

demand

,

g Q

Q =

2

gq

2

gd

gq

*

gd

*

*

q

2

gq

2

gd

gq

*

gd

*

*

d

V

V

V

P

V

Q

I

V

V

V

Q

V

P

I

+

−

=

+

−

=

*

d

I

*

q

I

+

-

abc

,

g

V

abc

dq

gd

V

gq

V

Total

,

WT

P

+

-

ref

,

dcg

V

+

-

LPF

g

,

dc

V

PI

abc

dq

PWM

1

S

2

S

e

,

dc

V

d

I

e

,

d

I

rest

P

e

,

b

P

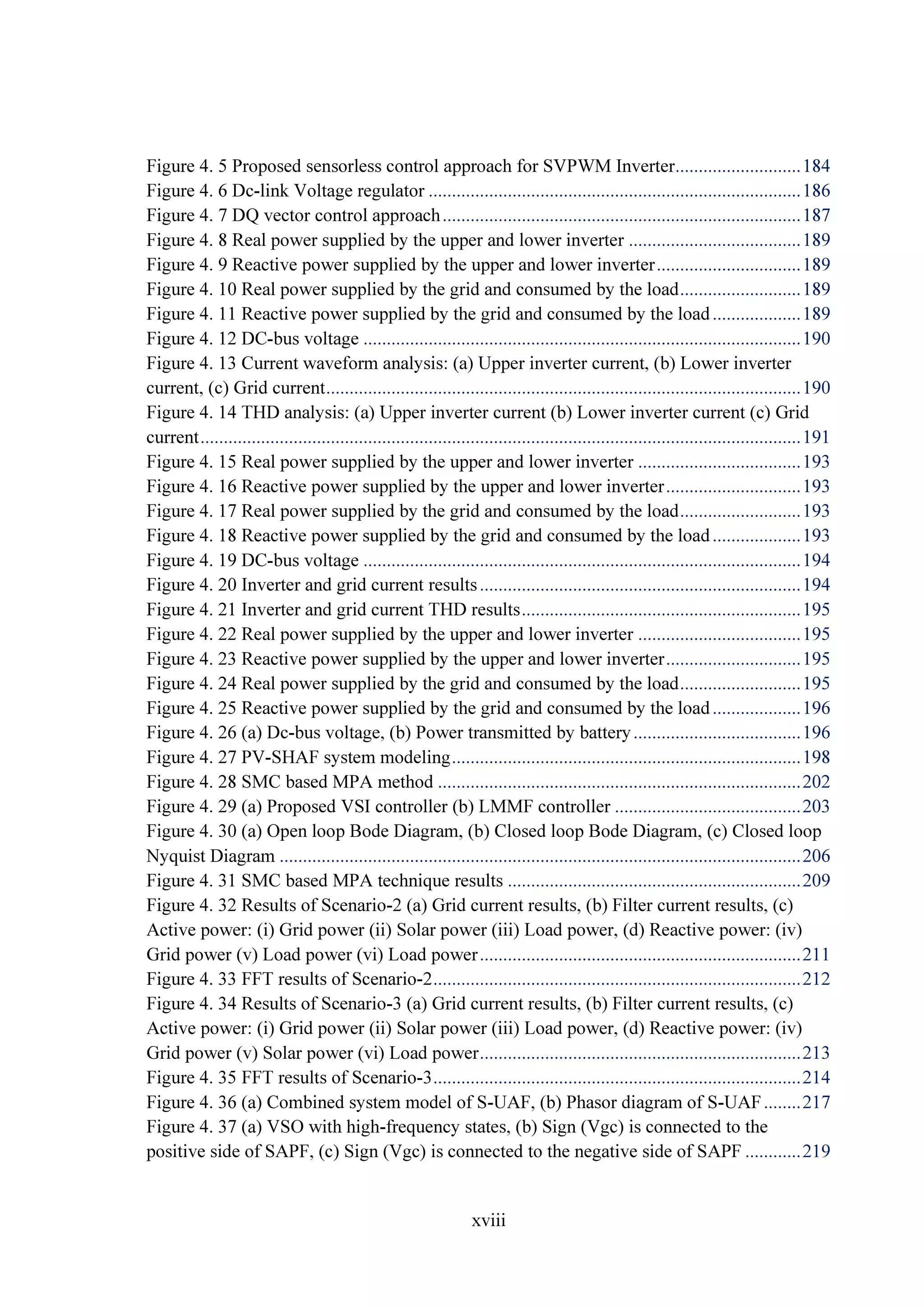

Figure 5. 5 Control approach for BES

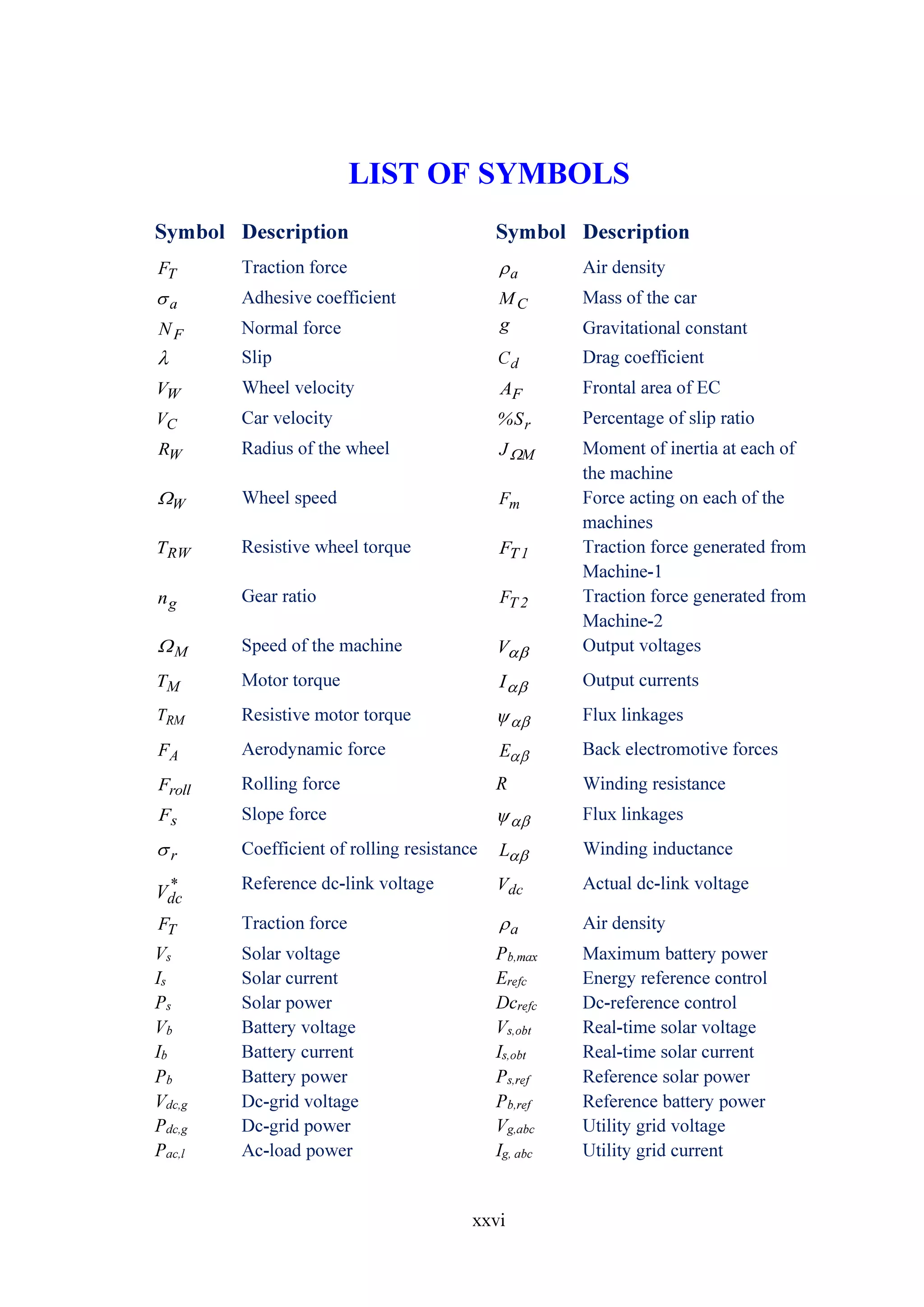

The BES control strategies mostly depend upon the DC-link voltage of the DC-grid, battery

SOC conditions, and grid/load demand. The complete control structure of BES is presented

in Figure 5. 5. Therefore, to increase battery durability, it is necessary to regulate the SOC

of the battery during GMO and IMO conditions. The detailed SOC management schemes are

presented in [273-278]. In the proposed approach, the reference battery power ( *

bat

P ) is

selected as per the SOC limit during both GMO and IMO conditions. At first, the grid active

and reactive power demand ( demand

,

g

P ) is fulfilled by the total generated power ( Total

,

WT

P

) of the wind turbine. According to the higher and lower limit of battery SOC, the charging

and discharging conditions are set. By comparing the rest power demand ( rest

P ) and battery

power error ( e

,

b

P ), the reference active grid power ( *

g

P ) is computed. The reactive power

demand ( demand

,

g

Q ) of the grid is equal to the reference reactive power ( *

g

Q ) of the system.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dr-211204045233/75/Robust-Active-Power-Filter-Controller-Design-for-Microgrid-and-Electric-Vehicle-Applications-part-2-45-2048.jpg)

![251

Chapter-5 HYBRID MICROGRID APPLICATION

After getting reference active and reactive power, the obtained powers are converted to

reference dq current component ( *

d

I and *

q

I ) [278]. The ac-load is connected to the ac-grid.

At the time of IMO, the ac-grid is detached from the main grid. To properly avail the charging

and discharging condition, the DC-grid information is also essential. Therefore, DC-grid

voltage ( g

,

dc

V ) is compared with the total DC-grid reference ref

,

dcg

V voltage, to generate

the appropriate voltage error ( e

,

dc

V ). e

,

dc

V is passed through the PI regulator, to generate

the linear active current component ( d

I ). The d

I is compared with *

d

I , to generate the error

in the active current component ( e

,

d

I ). After generating e

,

d

I and *

q

I component, the current

components are transformed to abc current component for generating appropriate pulses for

the battery converter operation.

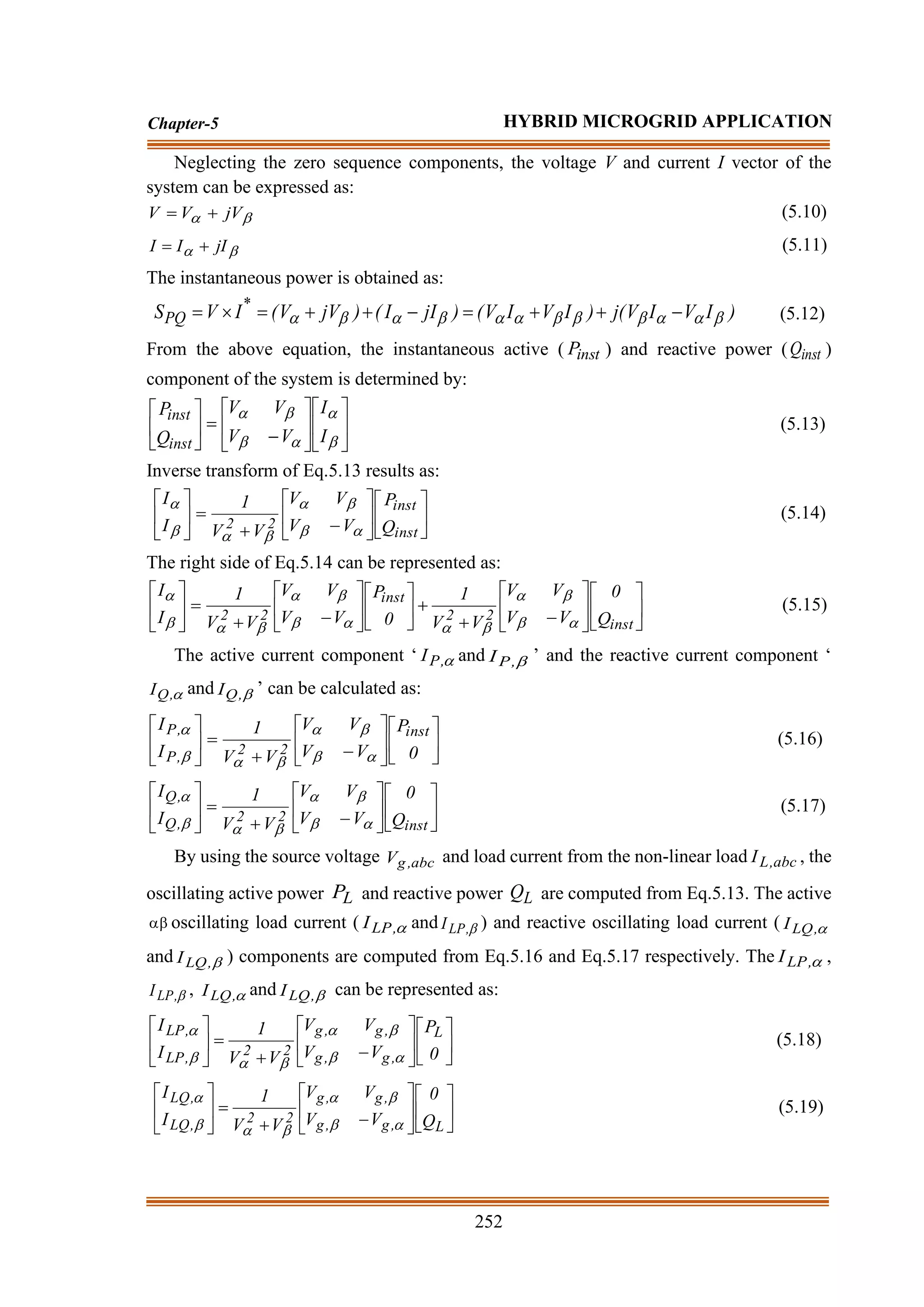

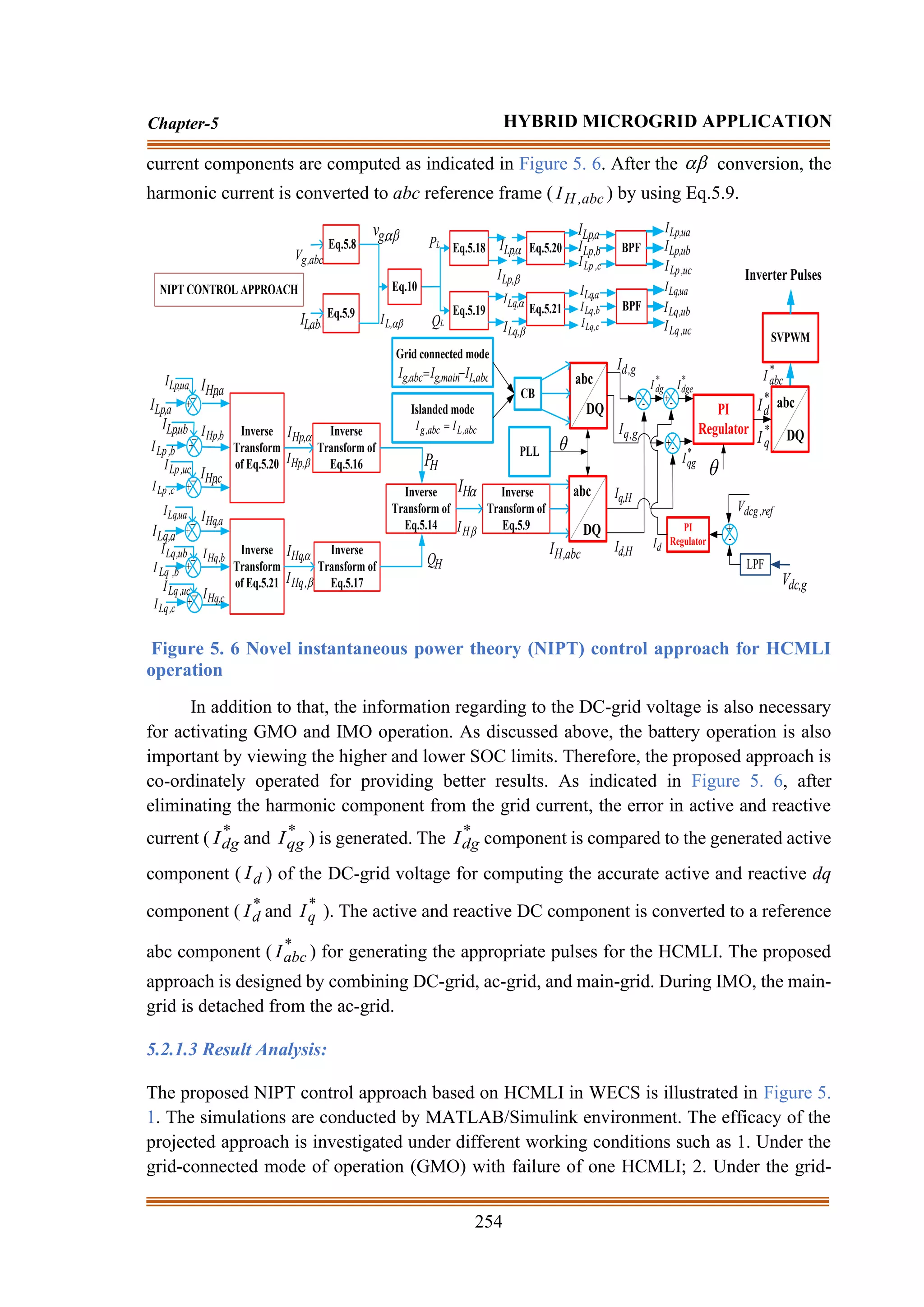

(c) Control Approach for a DC-ac Inverter:

The proposed NIPT approach is adopted for the inverter operation by generating the

actual reference current signal. The proposed approach easily separates the harmonics and

unbalanced components as shown in Figure 5. 6. After easily separating the oscillating

component, the positive sequence current component is used to generate the pulses for

HCMLI operation. The current component of the load and the voltage component of the grid

is transformed by the

−

abc transformation as follows.

=

−

−

−

=

0

g

g

g

0

0

g

g

g

abc

,

g

V

V

V

C

V

V

V

2

1

2

3

2

1

2

1

2

3

2

1

2

1

0

1

3

2

V

(5.6)

=

0

,

L

,

L

,

L

0

abc

,

L

I

I

I

C

I

(5.7)

The component of the grid voltage (

,

g

V ,

,

g

V ), and the load current (

,

l

I ,

,

l

I ) are

computed by neglecting the zero sequence components and represented as:

=

−

−

−

=

−

c

,

g

b

,

g

a

,

g

1

c

,

g

b

,

g

a

,

g

,

g

,

g

V

V

V

C

V

V

V

2

3

2

3

0

2

1

2

1

1

3

2

V

V

(5.8)

=

−

c

,

L

b

,

L

a

,

L

1

,

L

,

L

I

I

I

C

I

I

(5.9)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dr-211204045233/75/Robust-Active-Power-Filter-Controller-Design-for-Microgrid-and-Electric-Vehicle-Applications-part-2-46-2048.jpg)

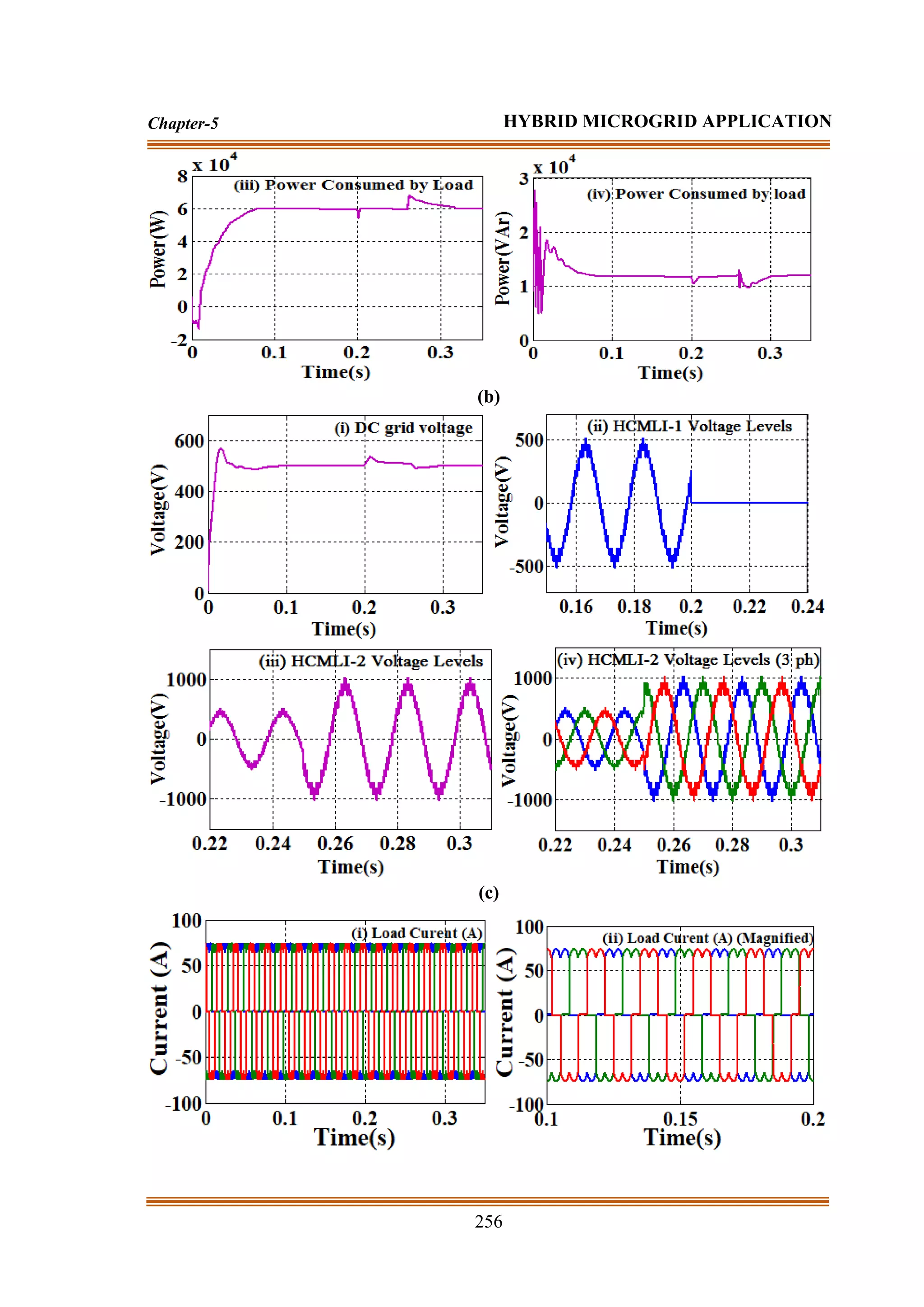

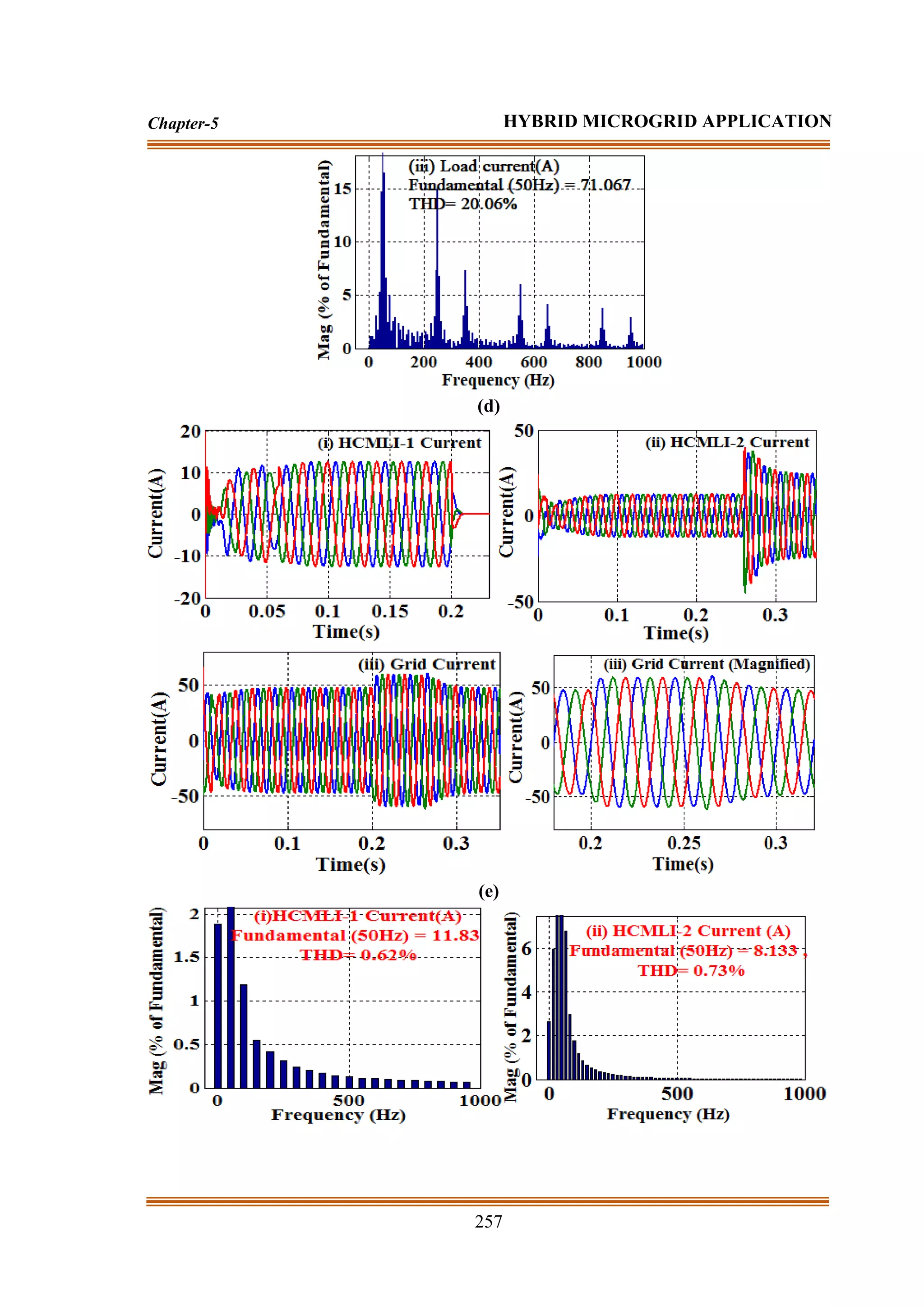

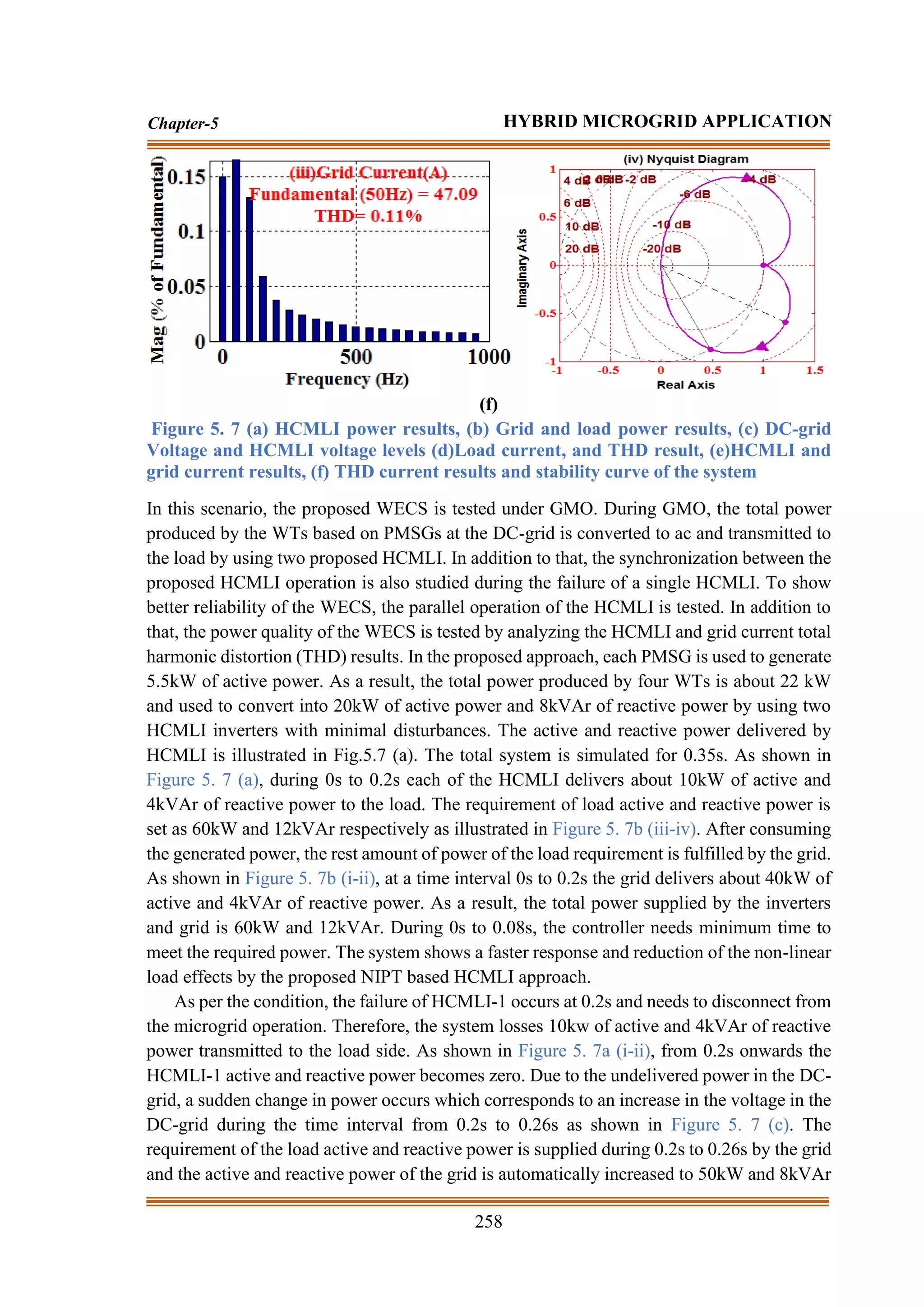

![255

Chapter-5 HYBRID MICROGRID APPLICATION

connected mode of operation with the integration of AC-DC converter; 3. Under the islanded

mode of operation (IMO). The system parameters considered in the simulation are

enumerated in the Appendix. The detailed data related to the distribution line are taken from

[287].

(a) First Scenario:

(a)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dr-211204045233/75/Robust-Active-Power-Filter-Controller-Design-for-Microgrid-and-Electric-Vehicle-Applications-part-2-50-2048.jpg)

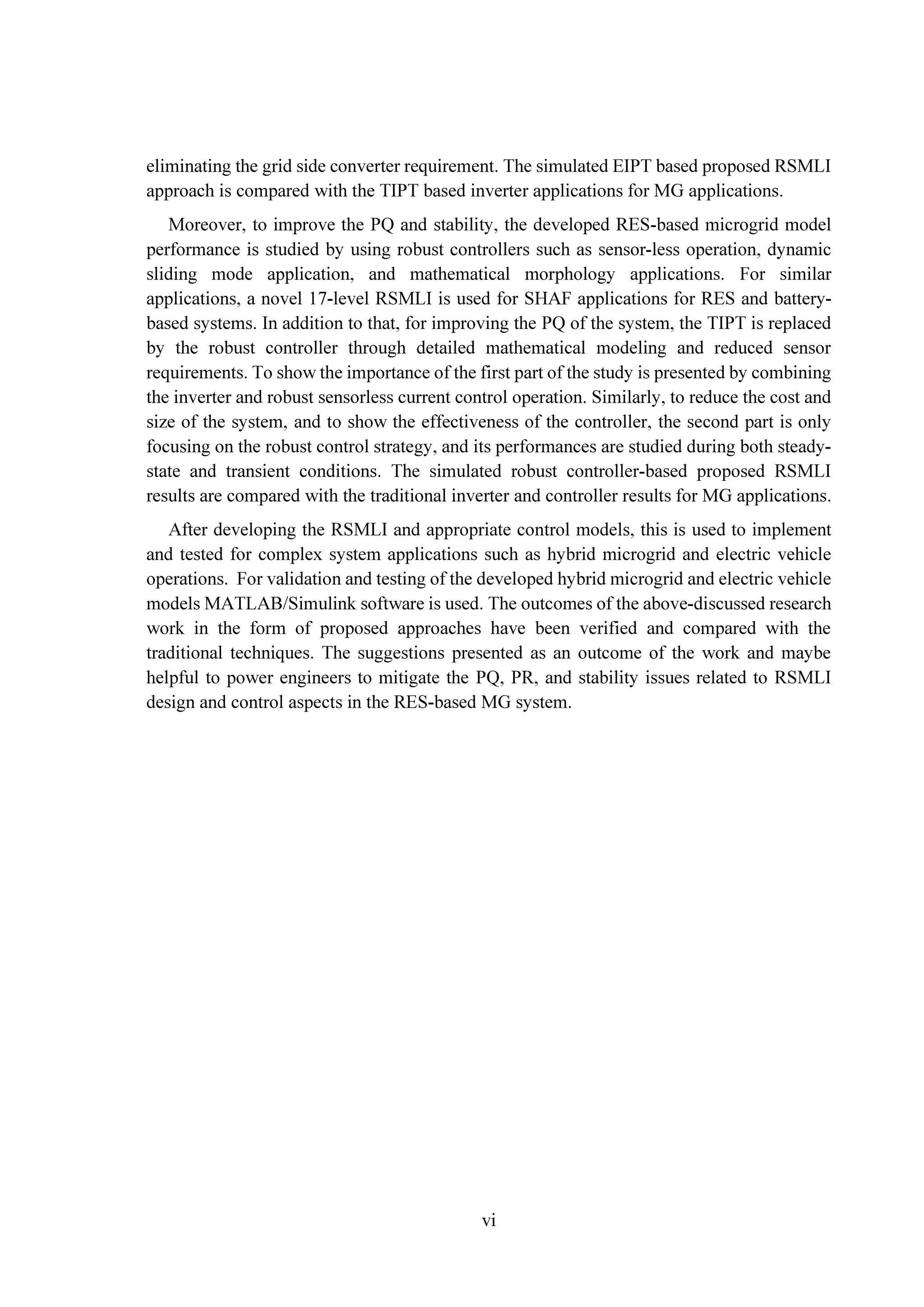

![267

Chapter-5 HYBRID MICROGRID APPLICATION

5.2.2 Study-2: A Novel Centralized Energy Management Approach for Power Quality

Improvement

5.2.1.1 Detailed operation of centralised management system (CEMS):

Solar

PV

S1

Boost Converter

DS D1

CS

L1

Lb

Vdc

S3

S2

C2

Battery

C1

Cb

Ib

Vdc

Buck-Boost Converter

S11 S13 S15

S14 S16 S12

Lf

Cf

CB

Voltage Source Inverter

dc-grid ac-grid

Centralized Energy Management Approach (CEMA)

Dc-load

Ac-load

Boost

Converter Pulses

Buck-Boost

Converter Pulses

Inverter Pulses

CB

CB

Ls Rs

ac-distribution

Grid

Transformer

P l

,

dc

P l

,

ac

Ps

Pb

Vs Is

Vs Is Ib

Vb

Vb SOC CB Ps Pb P l

,

dc P l

,

ac

Pg

Pg

Pac

Pac

V abc

,

g

V abc

,

g

Point of common

coupling (PCC)

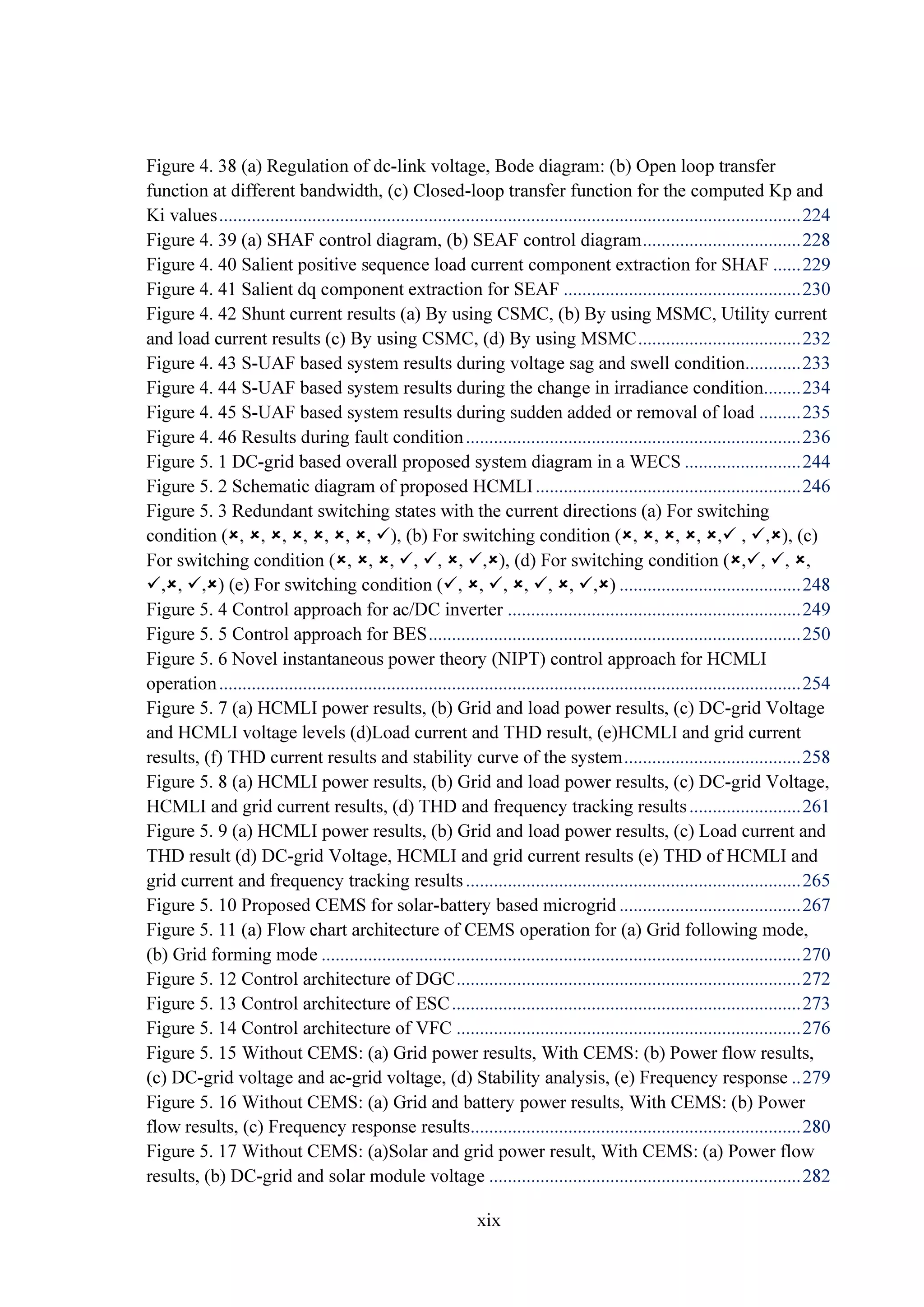

Figure 5. 10 Proposed CEMS for solar-battery based microgrid

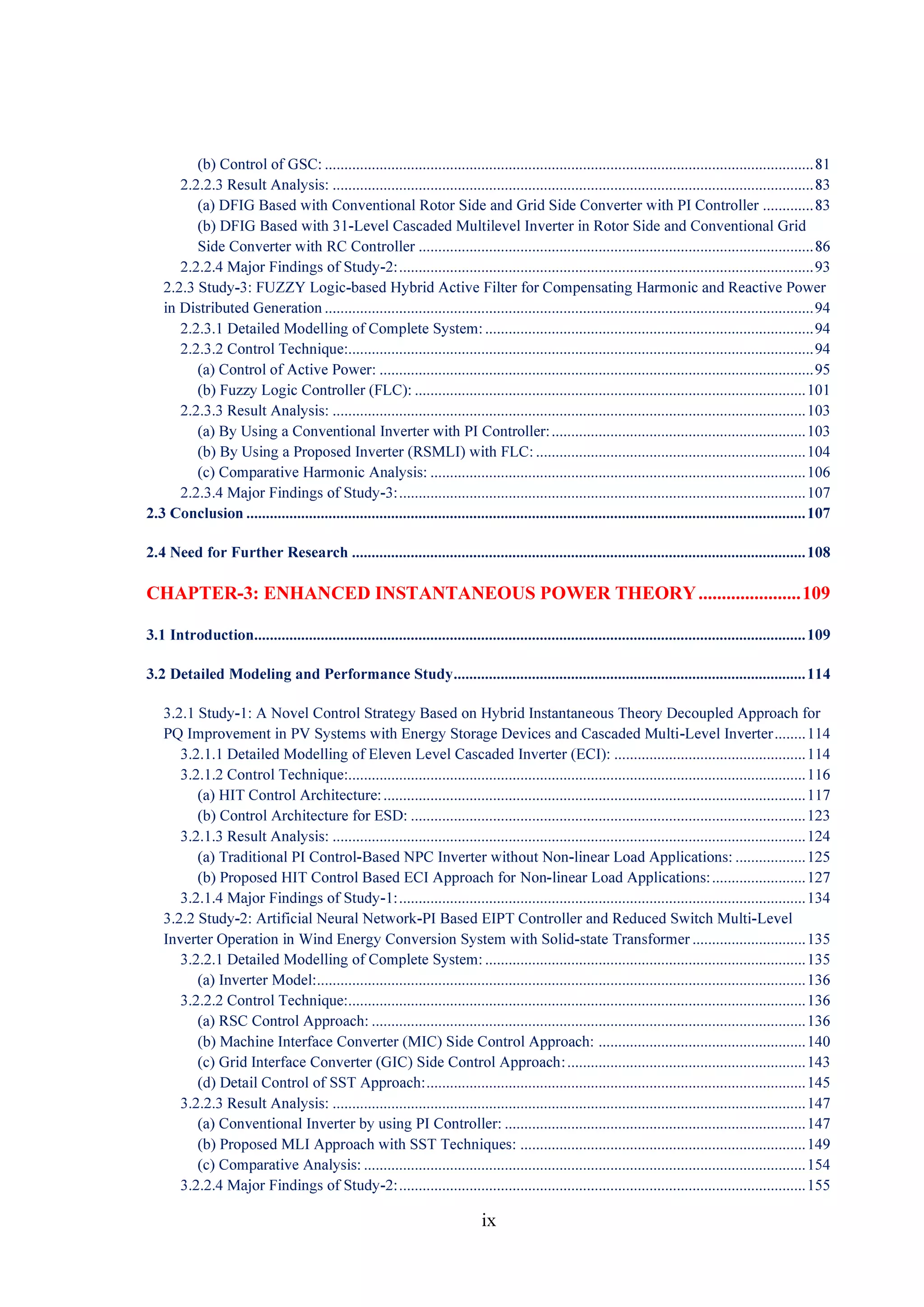

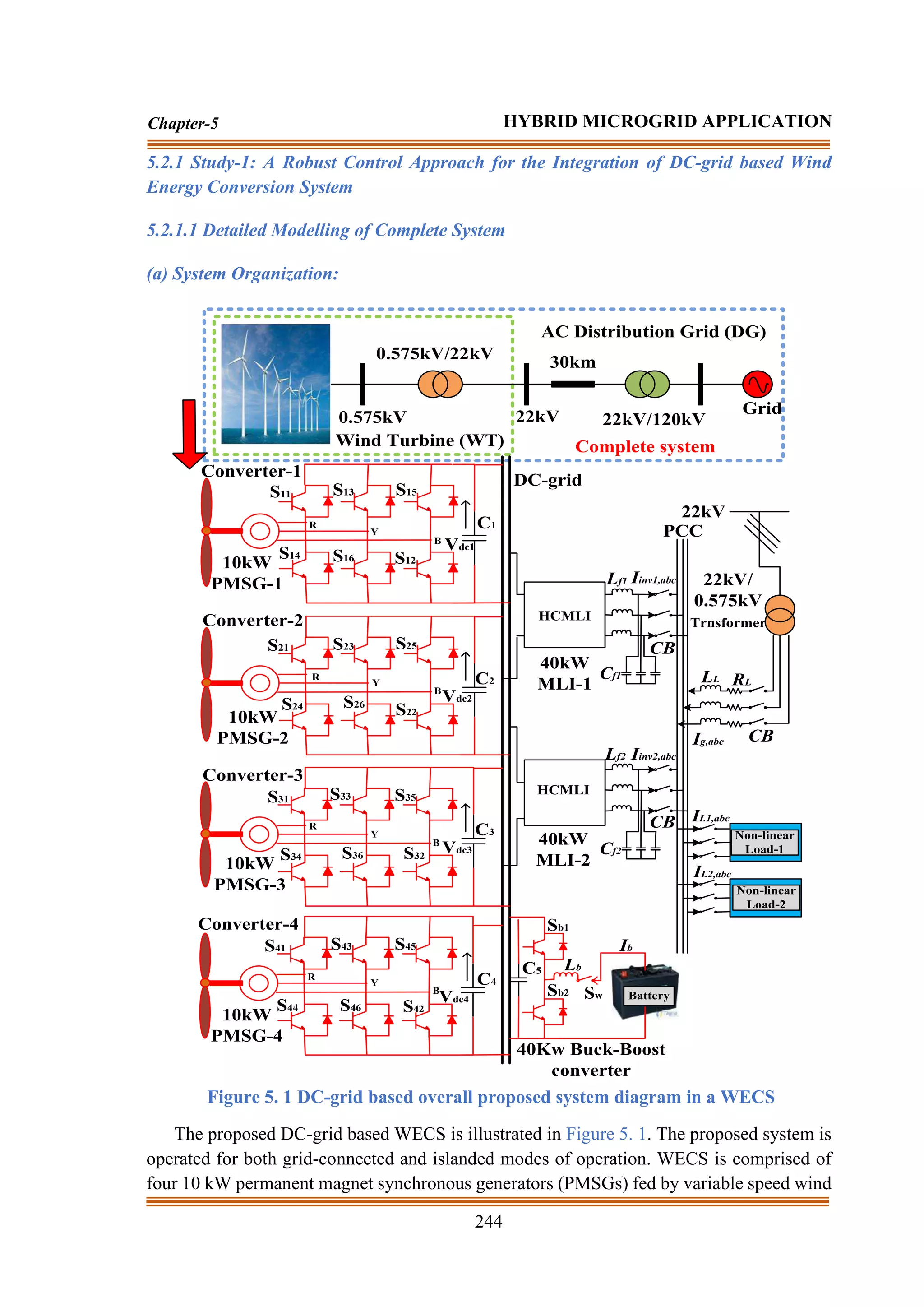

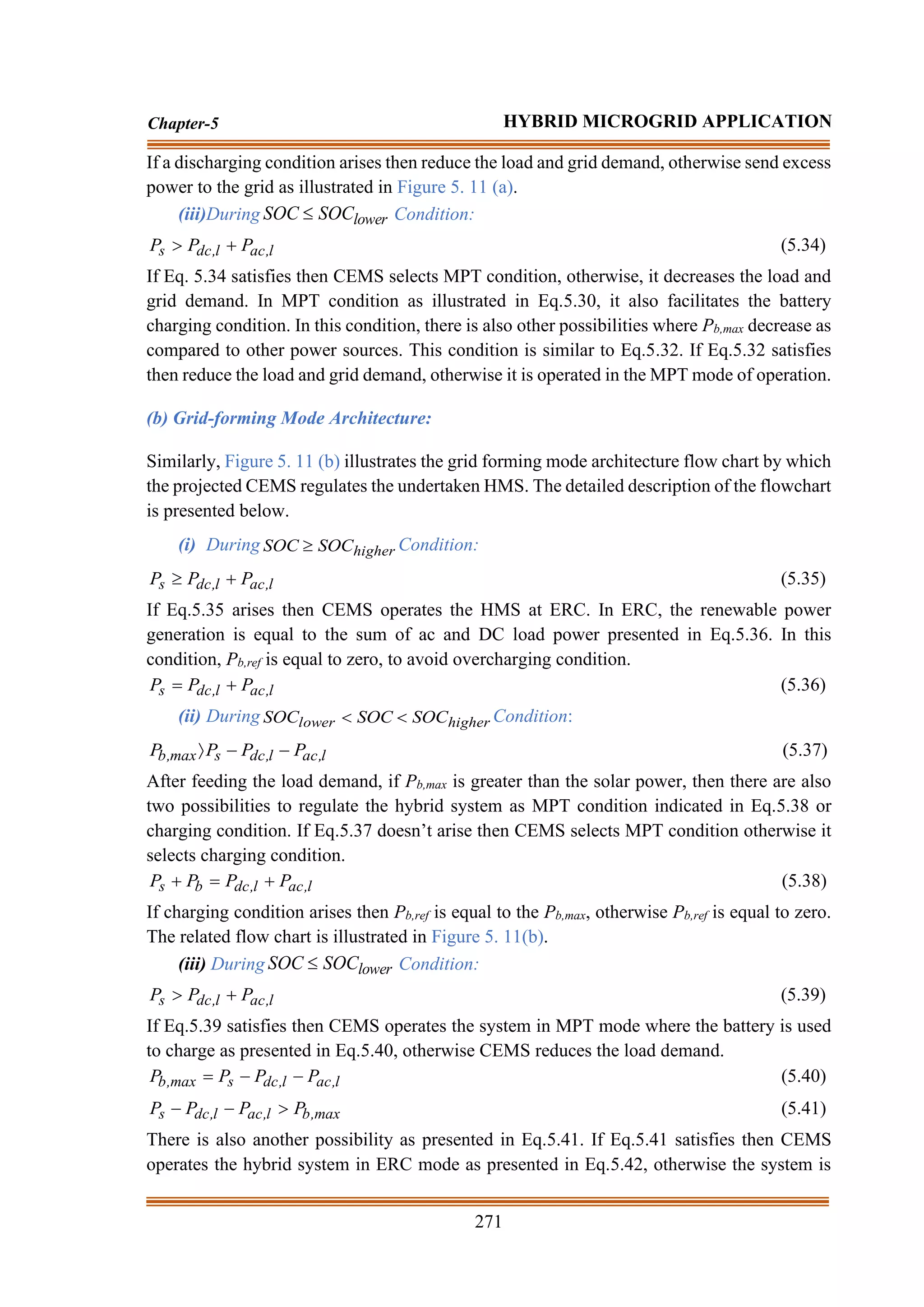

A typical arrangement of a combined solar-battery based hybrid grid (ac/DC) system is

demonstrated in Figure 5. 10. The proposed HMS is comprised of a solar array, BES device,

a bidirectional VSI, a DC-DC boost converter (BC), and a bidirectional buck-boost converter

(BBC) [318-319]. To extract optimum power, a BC is directly connected to the solar array,

and to avail optimal charging and discharging condition, a BBC is connected to the BES. For

the reliable power supply, a centralized DC-ac VSI is integrated between the ac and DC

microgrid. The DC and ac grid-based HMS facilitate the direct integration of the DC and ac

load without requiring any conversion device. From a real-time application point of view,

the DC-load examples are hybrid electric vehicles, laptop batteries, adapters, batteries,](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dr-211204045233/75/Robust-Active-Power-Filter-Controller-Design-for-Microgrid-and-Electric-Vehicle-Applications-part-2-62-2048.jpg)

![268

Chapter-5 HYBRID MICROGRID APPLICATION

chargers, and office buildings, etc. The designed hybrid system is connected to the utility

grid through a (208V:1.2kV) step-up transformer. To avail both grid-following and grid-

forming mode, a circuit breaker (CB) is connected to the HMS. During the severe fault at the

ac-grid, the CB may open to avoid the back feeding of current from the utility grid [320].

The projected HMS shown in Fig.1 is worked both grid-following and grid-forming

conditions. A similar type of undertaken system configuration is also widely employed and

tested in [315-316]. In this proposed approach, the projected CEMS is worked as a supervised

control module which regulates the active parameters such as solar voltage (Vs), solar current

(Is), battery current (Ib), battery voltage (Vb), grid voltage (Vg), state of charge (SOC), circuit

breaker (CB), solar power (Ps), battery power (Pb), ac-grid power (Pg), DC-load power

(PDC,l), and ac-load power (Pac,l), etc. As per the desired conditions, the proposed CEMS

selects appropriate control architecture to tackle the deteriorations and to provide a reliable

power supply. Though the proposed CEMS is modeled by using a solar-battery HMS as

indicated in Figure 5. 10, with proper modifications and appropriate technique there are also

other possibilities like decentralized VSI design or multiple energy storage device

integration. For both operating conditions, the detailed control architecture flow charts of the

proposed CEMS are demonstrated in Figure 5. 11(a-b).

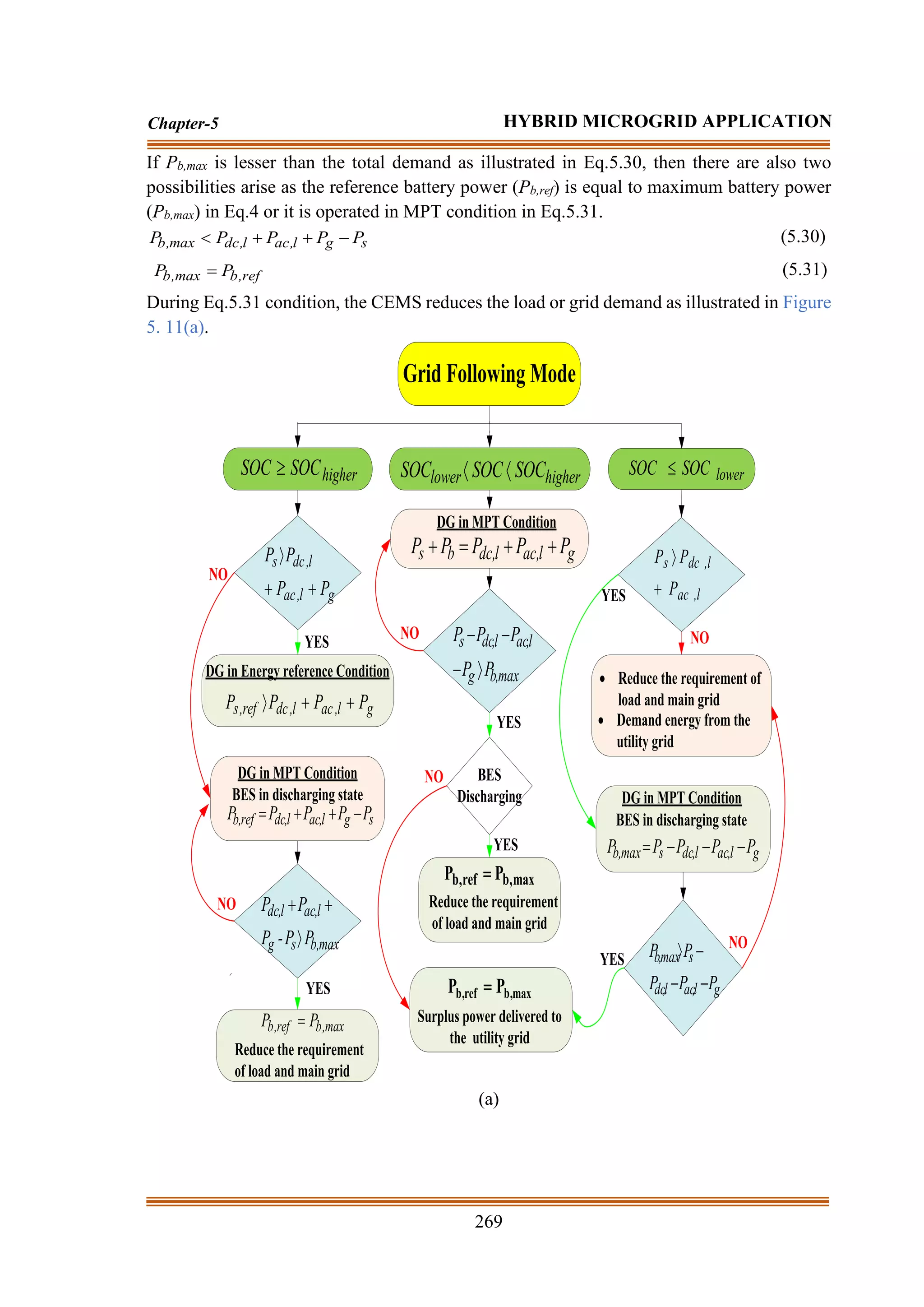

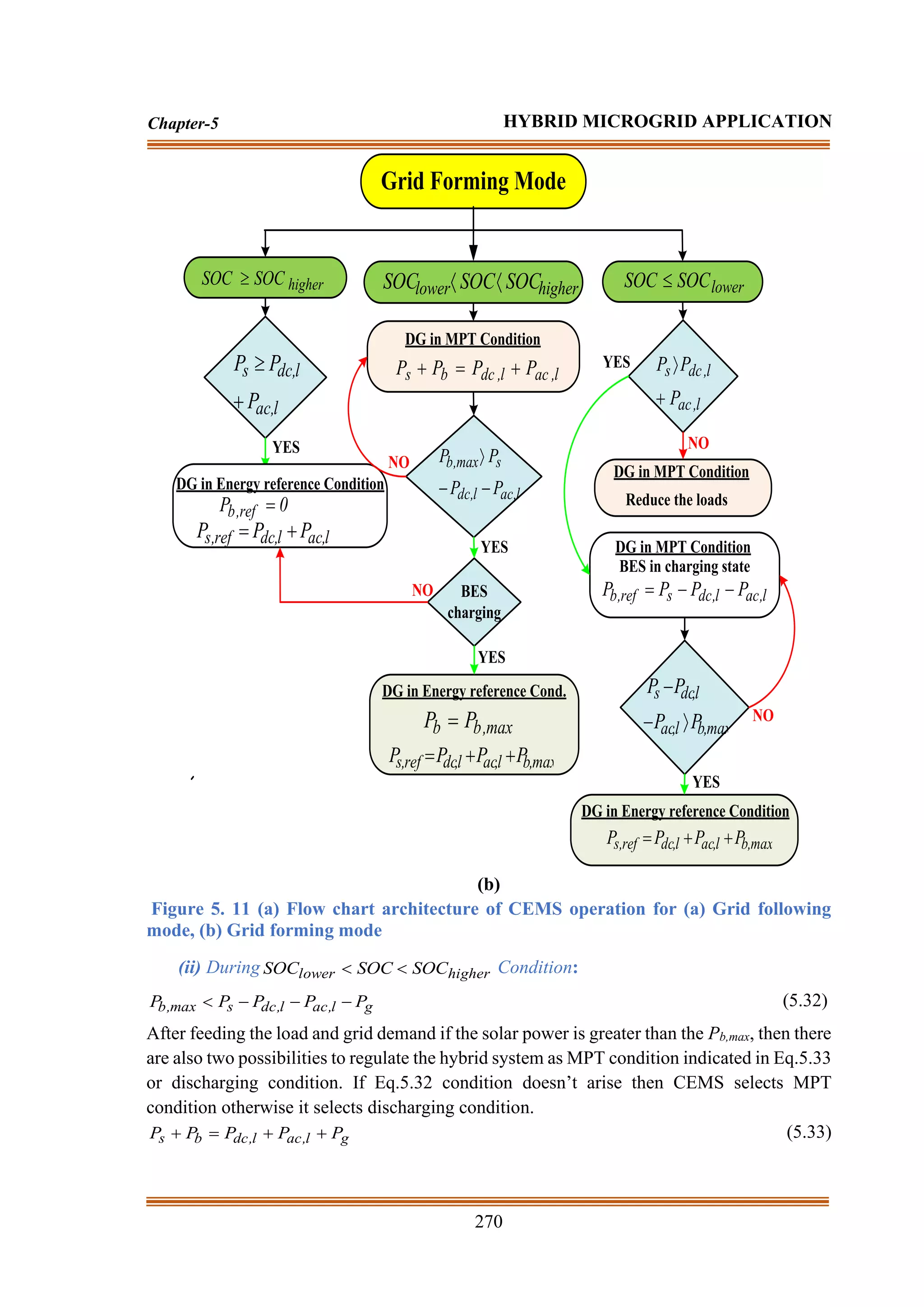

As presented in Figure 5. 10, the solar-battery based microgrid system is connected to the

utility grid through a CB. According to the requirement, deteriorations, and the plans of both

microgrid and utility, the CEMS decides by which mode and control technique the hybrid

system to be operated. As illustrated in Figure 5. 11(a-b), to avail a smooth power transfer in

both of the modes, the battery SOC functions such as higher

SOC

SOC ,

higher

lower SOC

SOC

SOC

, and lower

SOC

SOC are necessary to monitor. The higher

(90%) and lower (10%) values of SOC are regularly monitored, to avoid overcharging and

discharging conditions for increasing the life cycle of the battery [321].

(a) Grid-following Mode Architecture:

Figure 5. 11(a) illustrates the grid following mode architecture flow chart by which the

projected CEMS regulates the undertaken HMS. A detailed description of the flowchart is

presented below.

(i) During higher

SOC

SOC Condition:

During that period, there are two possibilities to regulate the HMS such as energy reference

condition (ERC) in Eq.5.28 and MPT condition in Eq.5.29. To avail the real power flow from

source to load and grid, the HMS must operate according to Eq.5.28.

g

l

,

ac

l

,

dc

s P

P

P

P +

+

(5.28)

If Eq.5.28 condition satisfies then the HMS is operated in ERF condition otherwise the

system is operated in MPT condition and the battery is used to start discharging. In MPT

conditions to fulfill the desired load demand, the HMS must operate according to Eq.5.29.

s

g

l

,

ac

l

,

dc

ref

,

b P

P

P

P

P −

+

+

= (5.29)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dr-211204045233/75/Robust-Active-Power-Filter-Controller-Design-for-Microgrid-and-Electric-Vehicle-Applications-part-2-63-2048.jpg)

![273

Chapter-5 HYBRID MICROGRID APPLICATION

condition, the Incremental Conductance (IC) based MPT algorithm is used [154,289,212] to

track maximum power under different irradiance and temperature condition [1]. The

instantaneous voltage and current result of the solar is denoted as Vs,obt, and Is,obt respectively.

The energy-reference control (Erefc) mode is activated by comparing the Ps and the reference

of solar power (Ps,ref). The DC-reference control (DCrefc) mode is activated by comparing the

DC-grid voltage (VDC,g) and the reference DC-grid voltage (VDC,ref). Depending on the test

scenarios, the proposed DGC controller is operated by considering three important factors

such as MPT control, Erefc, and DCrefc mode. After comparing the instantaneous signals with

the reference signals, the error signals such as an error in power (Pse), error in solar voltage

(Vse), and error in DC grid voltage (VDC,e) are passed through the PI regulator to linearize the

outputs and used to provide the necessary pulses for the converter operation.

For example, in Grid forming mode, if l

ac,

l

dc,

mpp

,

s P

P

P +

and the BES is fully charged

(Pb >Pb,max), the proposed CEMS generates the control commands such that the Erefc = 1, and

DCrefc = 0. As shown in Figure 5. 11(a-b), due to the above command the solar array is set to

work in the Erefc mode to produce the pulses for boost converter operation. In this case, to

balance the power flow, the CEMS will choose the appropriate Ps,ref for the solar array by

selecting the proper Vs,obt. The Vs,obt is lying in between the open-circuit voltage (Voc) and the

MPP voltage (Vs). As VDC,g is controlled through the energy storage device buck-boost

converter then in this condition, the voltage across the grid is maintained constant even under

solar power fluctuation situations. In addition to that when the battery is inactive (under fault

condition), the boost converter has shifted the power flow to maintain the DC-grid voltage

for a continuous power supply to the load by giving the command Erefc=0 and DCrefc =1.

Therefore, in this condition, only DCrefc is activated. In the MPP case, the proposed CEMS

generates the control commands Erefc= 0 and DCrefc=0, where the real-time voltage (Vs.obt)

and current (Is,obt) values of the solar array are computed and sent to the MPT module for

generating the maximum power point voltage (Vs). The DGC controller is designed by

considering the above three conditions as illustrated in Figure 5. 12. Note that the

simultaneous activation of Erefc and DCrefc is not relevant.

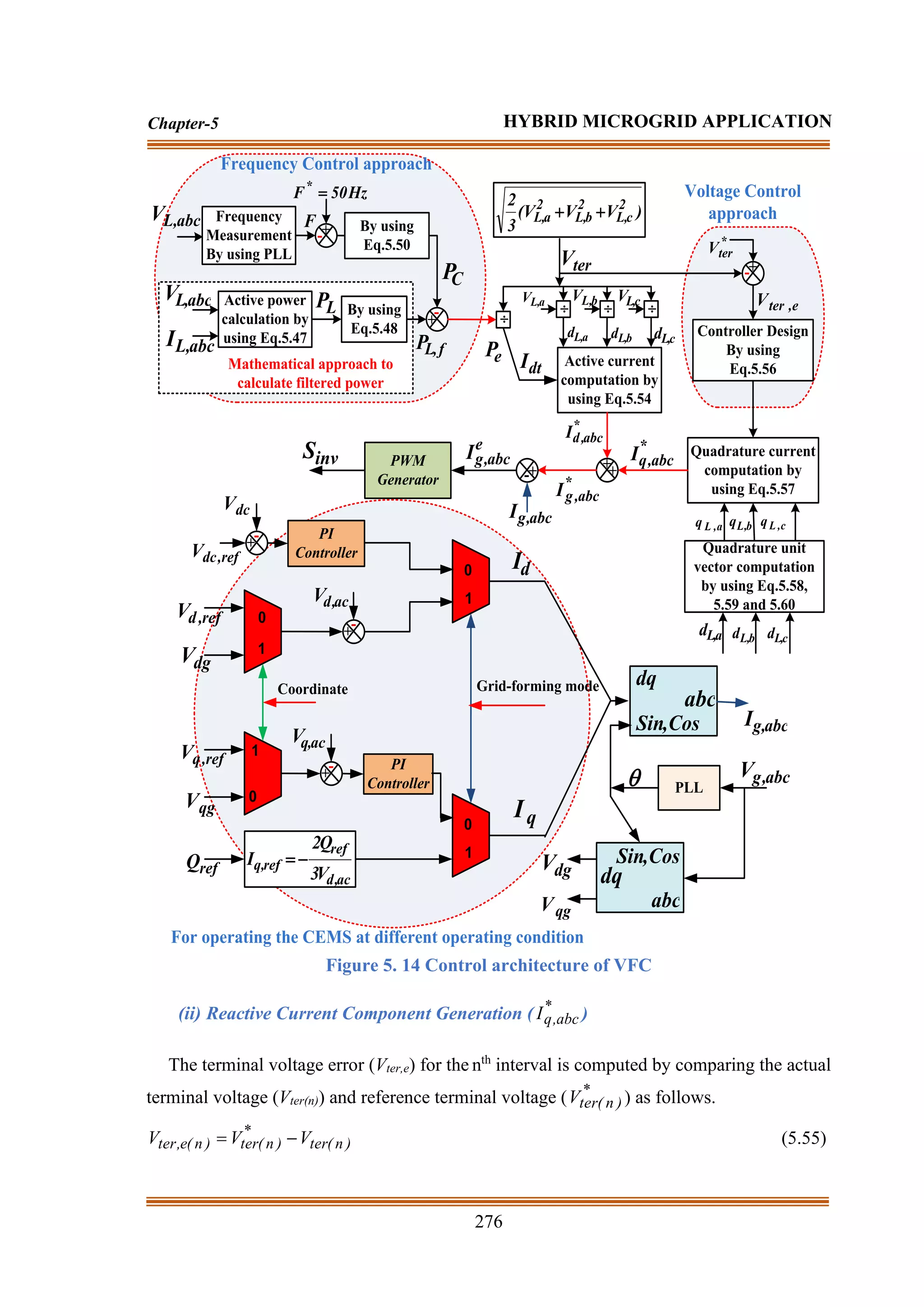

(b) Energy Storage Controller (ESC):

>0?

ref

,

b

P

Y

N

0

T

,

1

T 2

1 =

=

1

T

,

0

T 2

1 =

=

+

-

+-

b

P 0

1

PI

Controller

PWM

g

,

dc

V

ref

,

dc

V

1

T

2

T

2

S

3

S

dc-reference

control (Dcrefc)

1= Activate Condition

0= Deactivate Condition

Figure 5. 13 Control architecture of ESC](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dr-211204045233/75/Robust-Active-Power-Filter-Controller-Design-for-Microgrid-and-Electric-Vehicle-Applications-part-2-68-2048.jpg)

![275

Chapter-5 HYBRID MICROGRID APPLICATION

)

V

2

1

V

2

1

V

(

3

2

V c

,

L

b

,

L

a

,

L

L −

−

=

(5.43)

)

V

2

3

V

2

3

(

3

2

V c

,

L

b

,

L

L −

=

(5.44)

)

I

2

1

I

2

1

I

(

3

2

I c

,

L

b

,

L

a

,

L

L −

−

=

(5.45)

)

I

2

3

I

2

3

(

3

2

I c

,

L

b

,

L

L −

=

(5.46)

L

L

L

L

L I

V

I

V

P +

= (5.47)

To supress the limitations of the numerical LPF, in the proposed approach a mathematical

average technique (MAT) is suggested to obtain the filtered DC load power (PL,f). The

proposed MAT is presented as follows.

=

T

0

L

f

,

L dt

P

T

1

P (5.48)

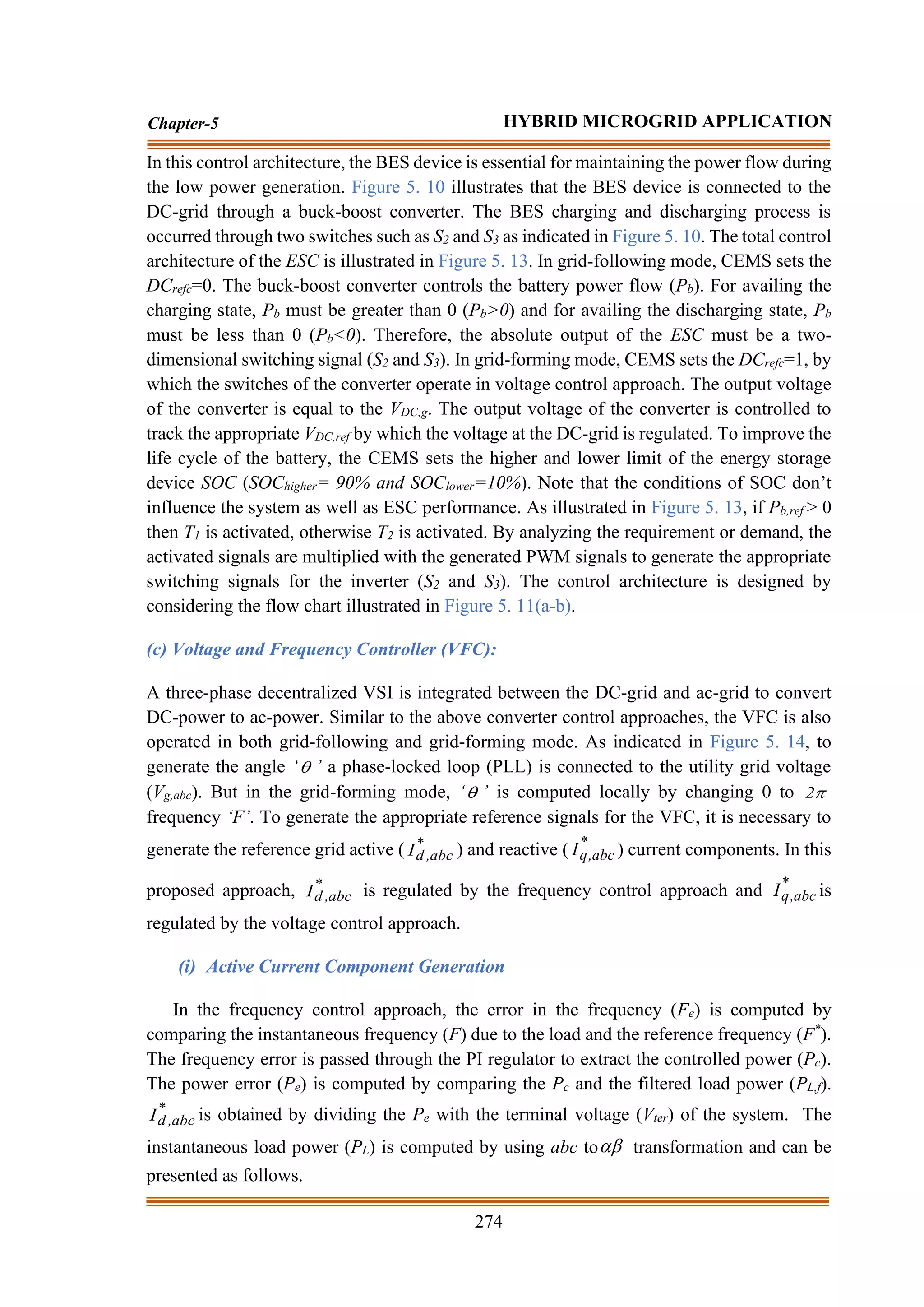

T denotes the total time duration of the circuit operation. As illustrated in Figure 5. 14, the

VL,abc is passed through PLL to produce the F. F*

of the system is chosen as 50Hz. Fe is

computed as:

)

n

(

F

)

n

(

F

)

n

(

F *

e −

= (5.49)

For nth

sampling instant, the output of frequency error is passed through the PI controller to

generate PC as follows.

)

n

(

F

K

)}

1

n

(

F

)

n

(

F

{

K

)

1

n

(

P

)

n

(

P e

IF

e

e

PF

C

C +

−

−

+

−

= (5.50)

where KPF and KIF denote as the proportional and integral frequency constant of the PI

controller respectively. The detailed controller design procedure is presented in [3], [5], and

[25]. The instantaneous load terminal voltage (Vter) is computed as:

2

1

2

c

,

L

2

b

,

L

2

a

,

L

ter )

V

V

V

(

3

2

V

+

+

= (5.51)

By using the PC, PL,f, and Vter, the active current component (Idt) is computed as:

ter

C

f

,

L

dt

V

3

)

P

P

(

2

I

−

= (5.52)

The active unity amplitude parameters (dL,a, dL,b, and dL,c) depend upon the instantaneous

load voltage (VL,abc) and the terminal amplitude load voltage (Vter).

The unity amplitude parameters are presented as:

ter

a

,

L

a

,

L

V

V

d = ;

ter

b

,

L

b

,

L

V

V

d = ; and

ter

c

,

L

c

,

L

V

V

d = (5.53)

From Eq.5.38, the generated instantaneous reference active current can be computed as:

a

dt

*

da d

I

I = ; b

dt

*

db d

I

I = ; and c

dt

*

dc d

I

I = (5.54)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dr-211204045233/75/Robust-Active-Power-Filter-Controller-Design-for-Microgrid-and-Electric-Vehicle-Applications-part-2-70-2048.jpg)

![278

Chapter-5 HYBRID MICROGRID APPLICATION

(Vdg and Vqg), the angle is generated by using the PLL block. After the breaker operation

as shown in Figure 5. 14, Vdg and Vqg are chosen as the reference voltage for the ac-grid

voltage.

To avoid the overloading condition, it is essential to regulate the dq current component (Id

and Iq). After generating the proper Id and Iq current component, it is converted to abc current

component (Ig,abc). As discussed above, the reference current signal ( *

abc

,

g

I ) is produced.

To generate the error signal ( e

abc

,

g

I ), the Ig,abc, and *

abc

,

g

I currents are compared and passed

through a PWM controller to produce the appropriate pulses for inverter operation.

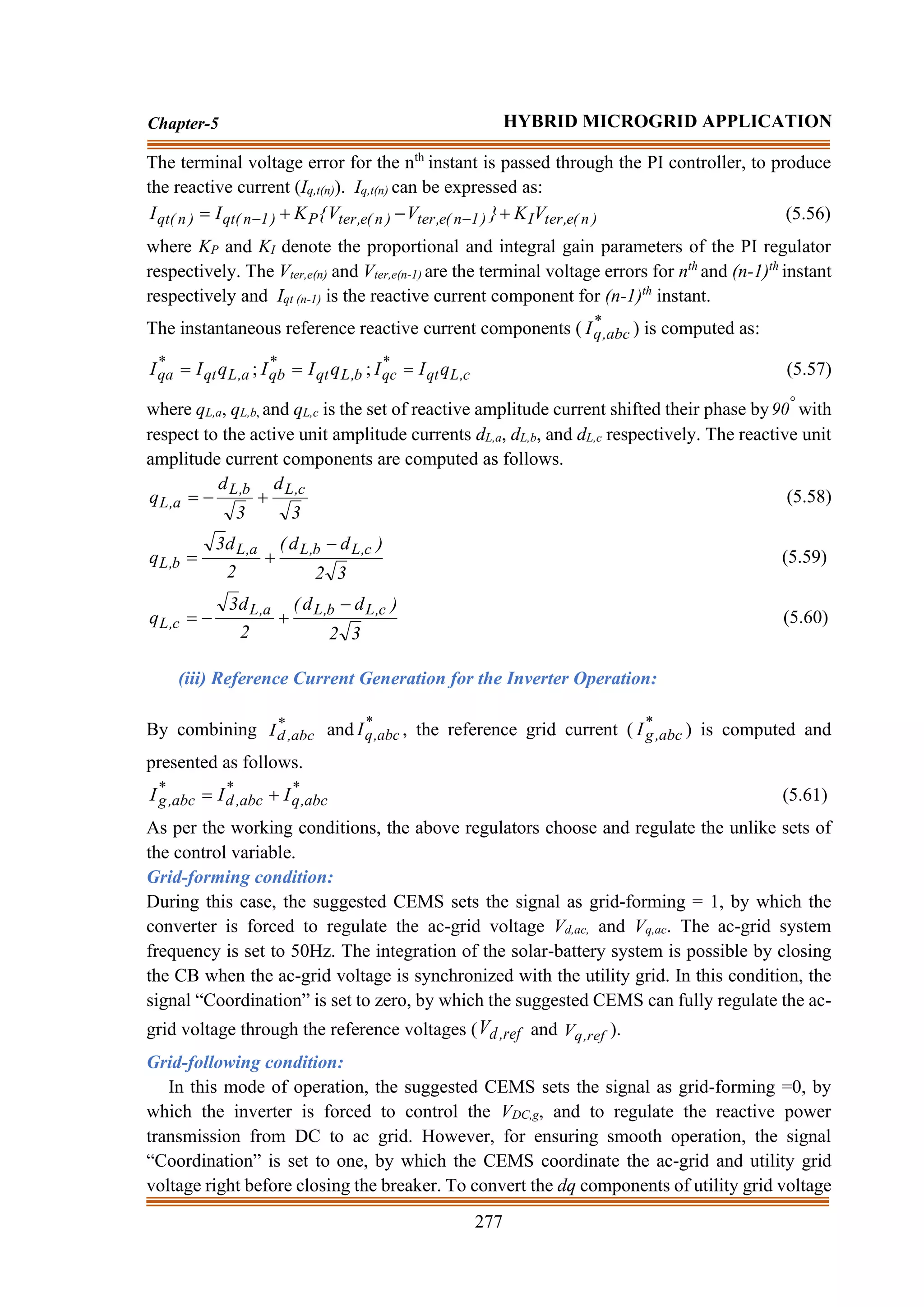

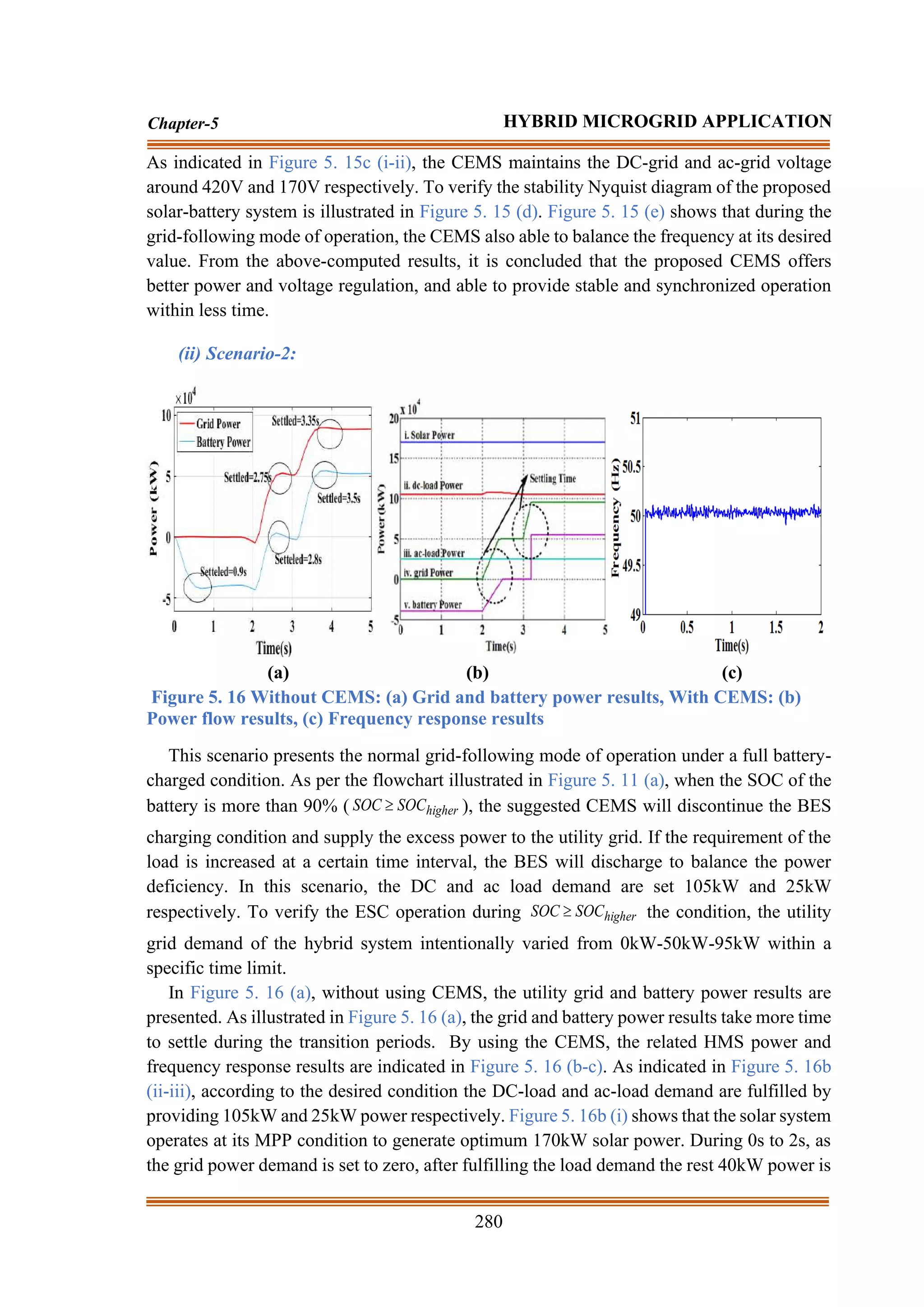

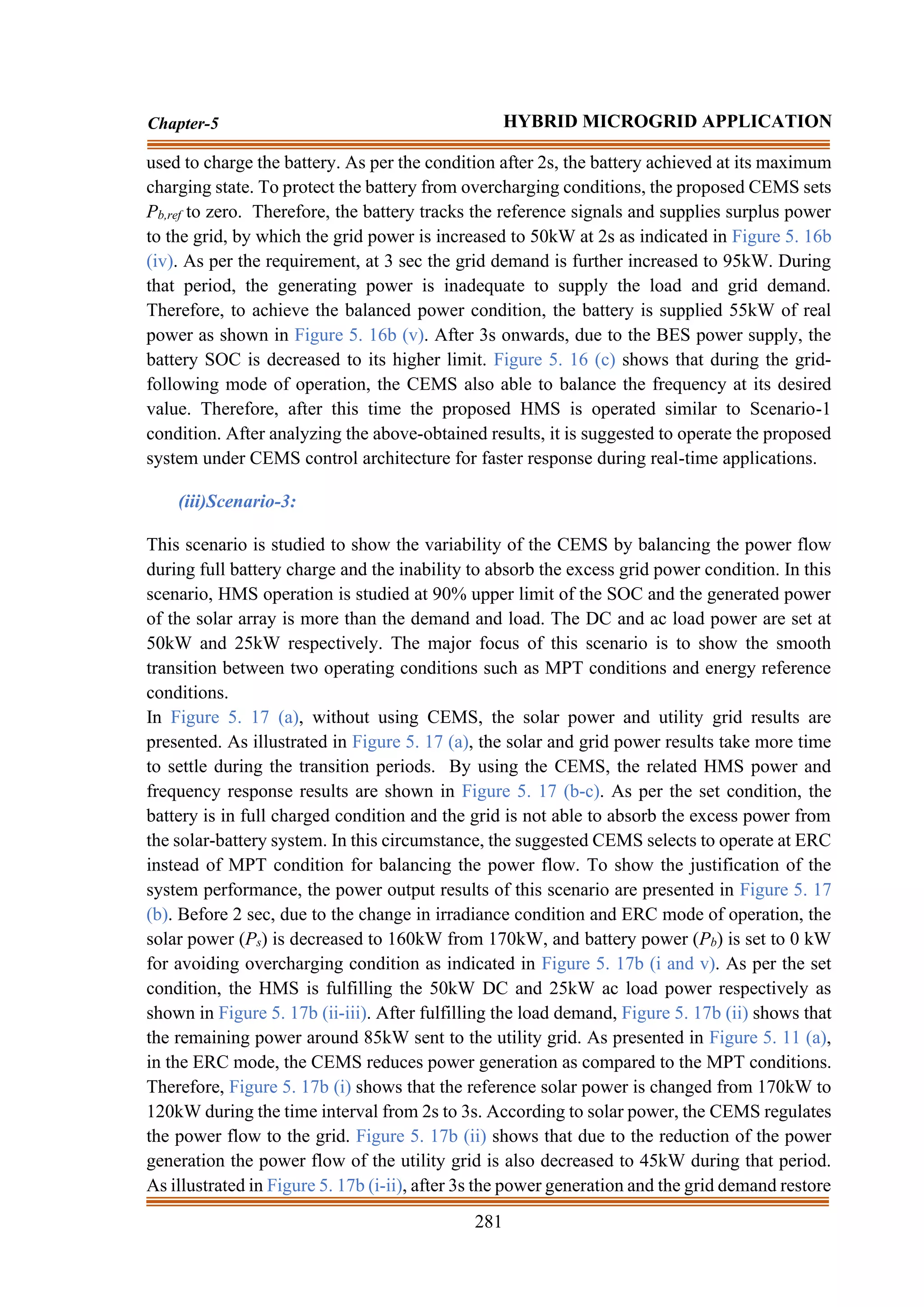

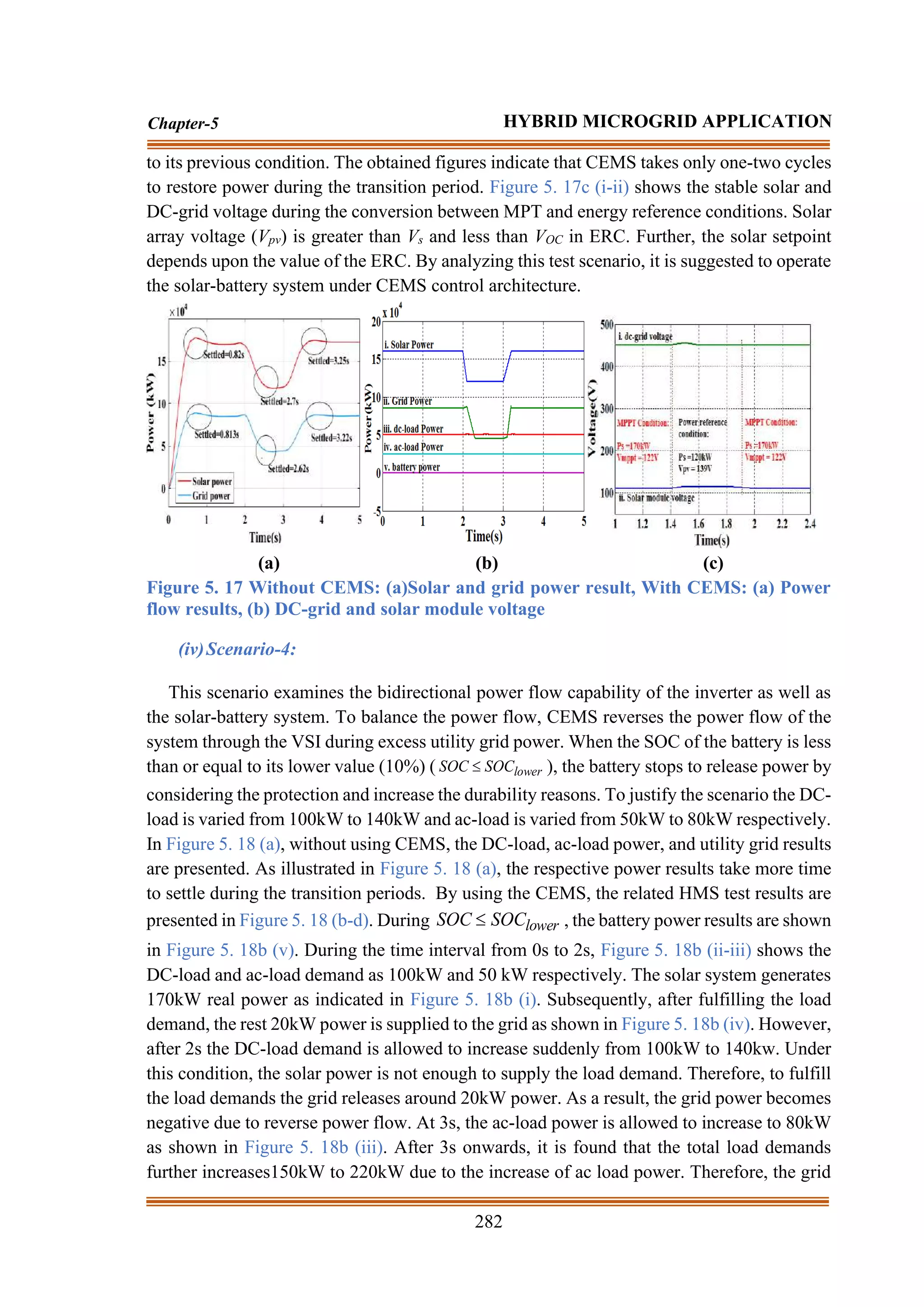

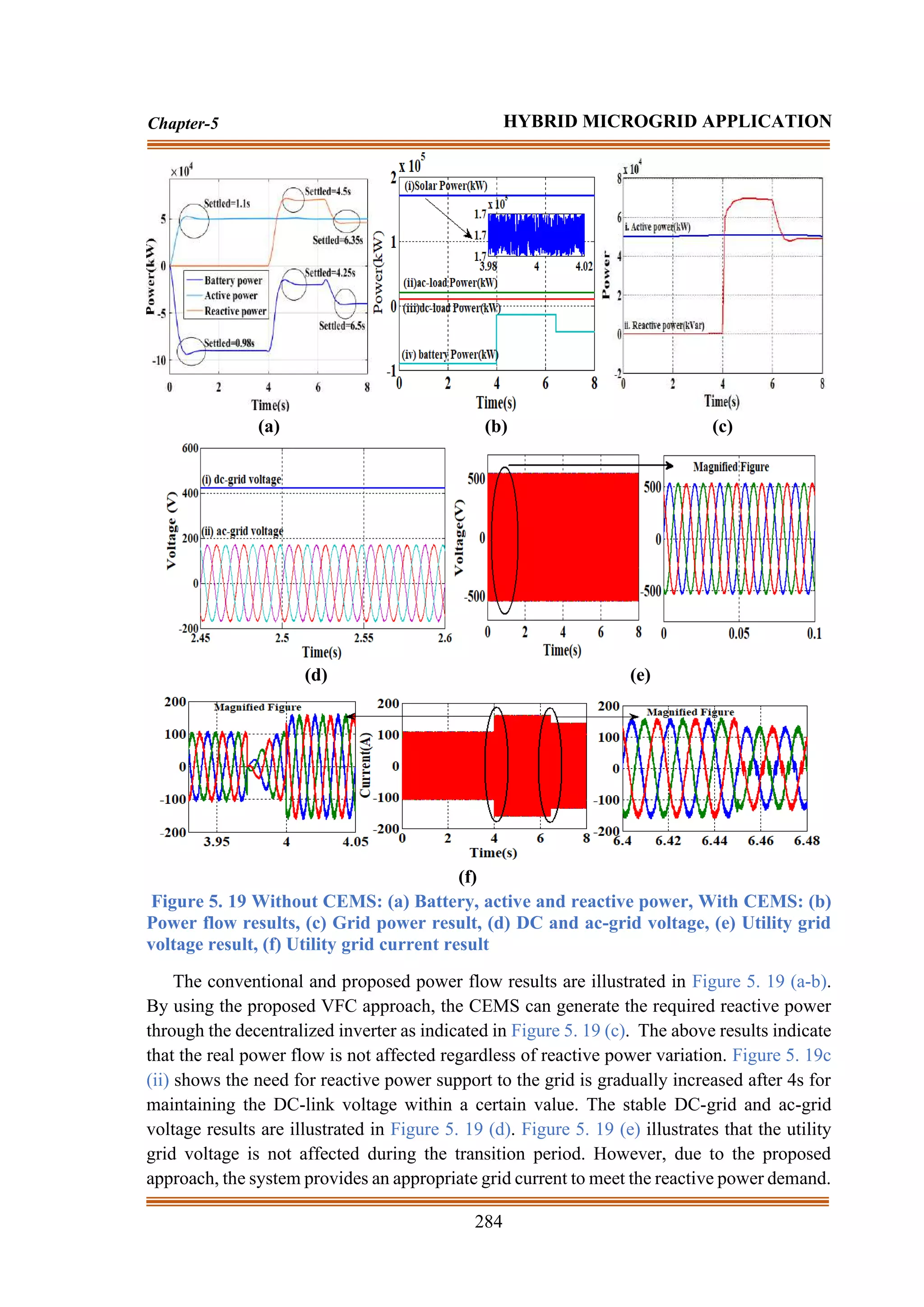

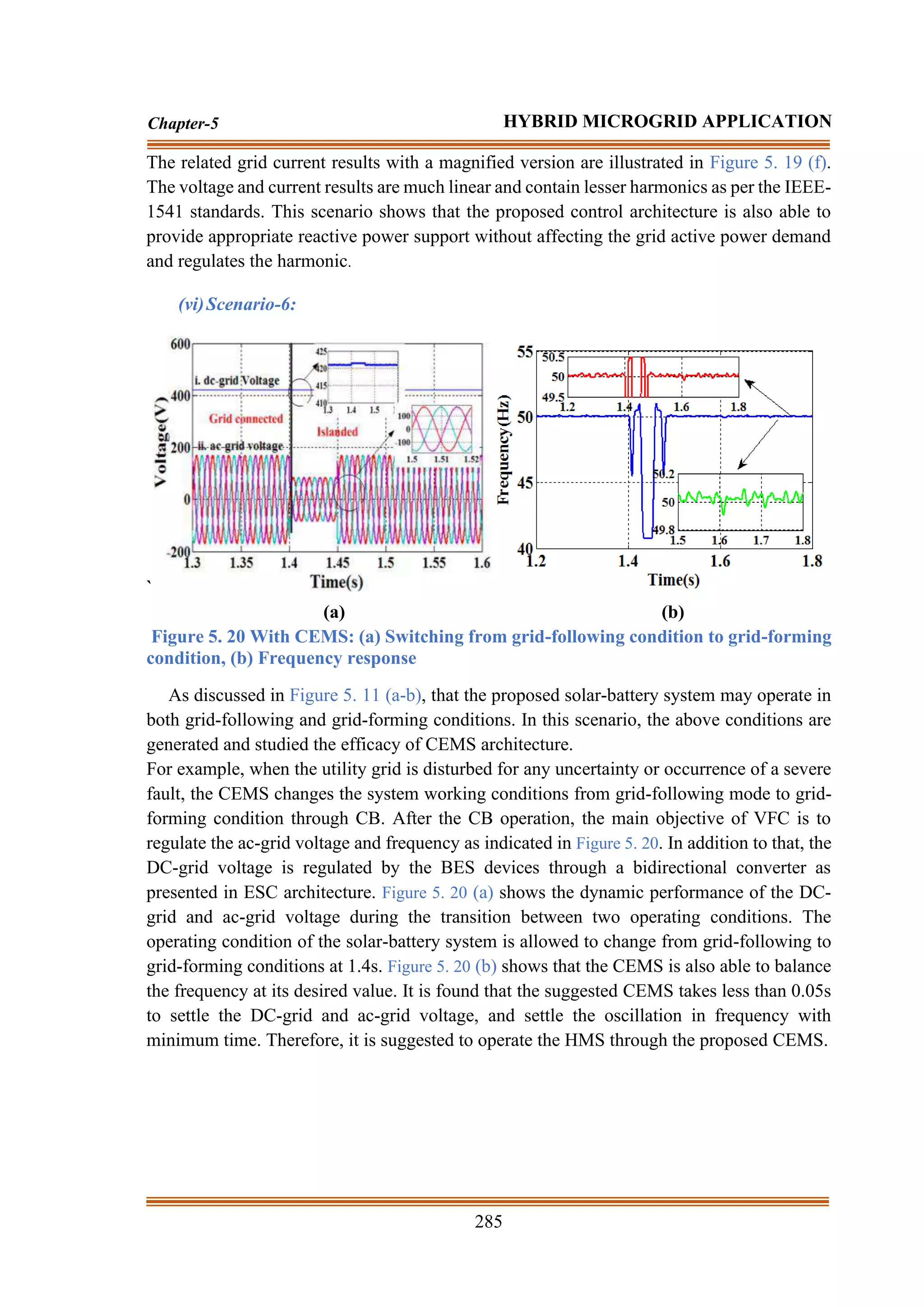

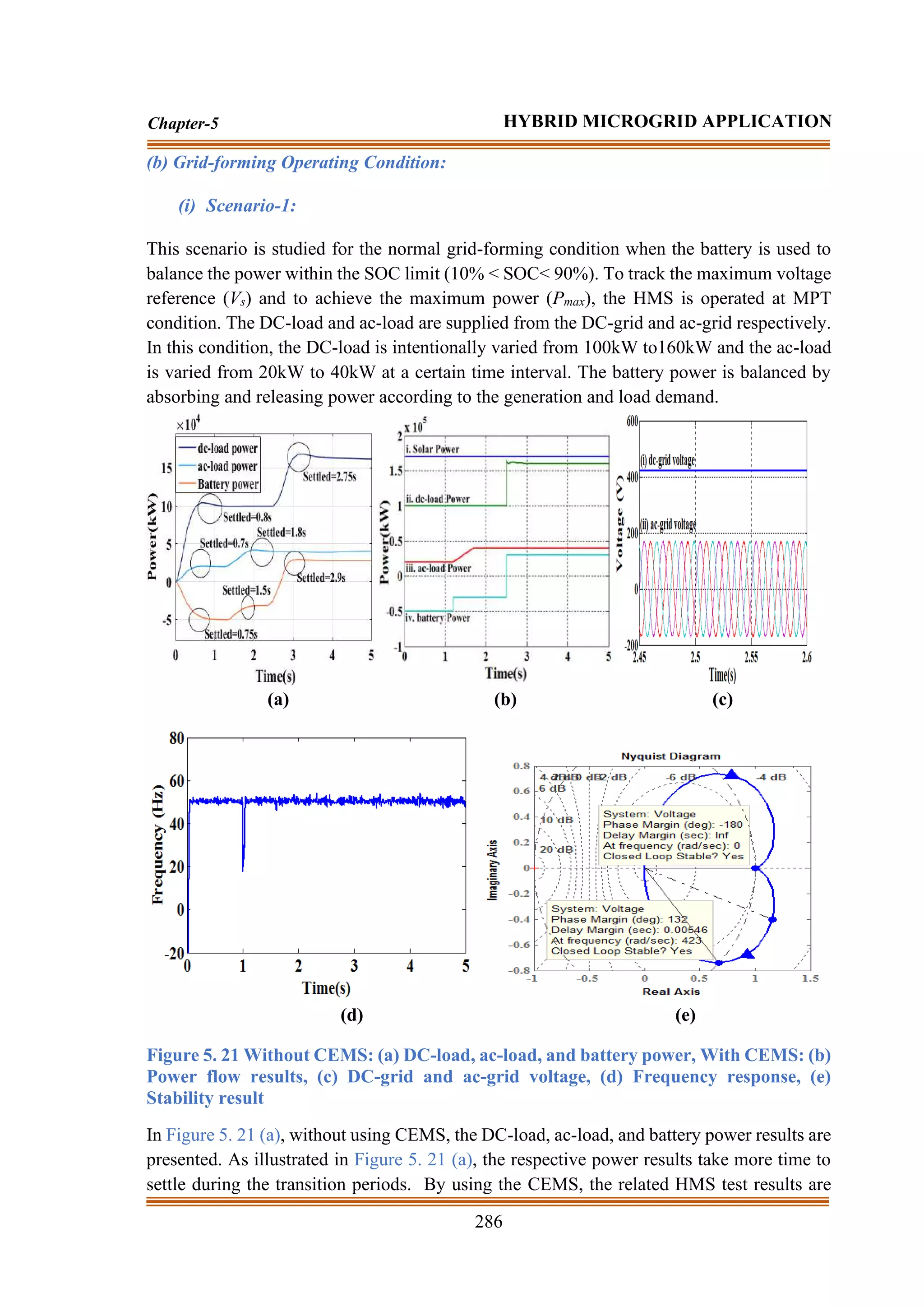

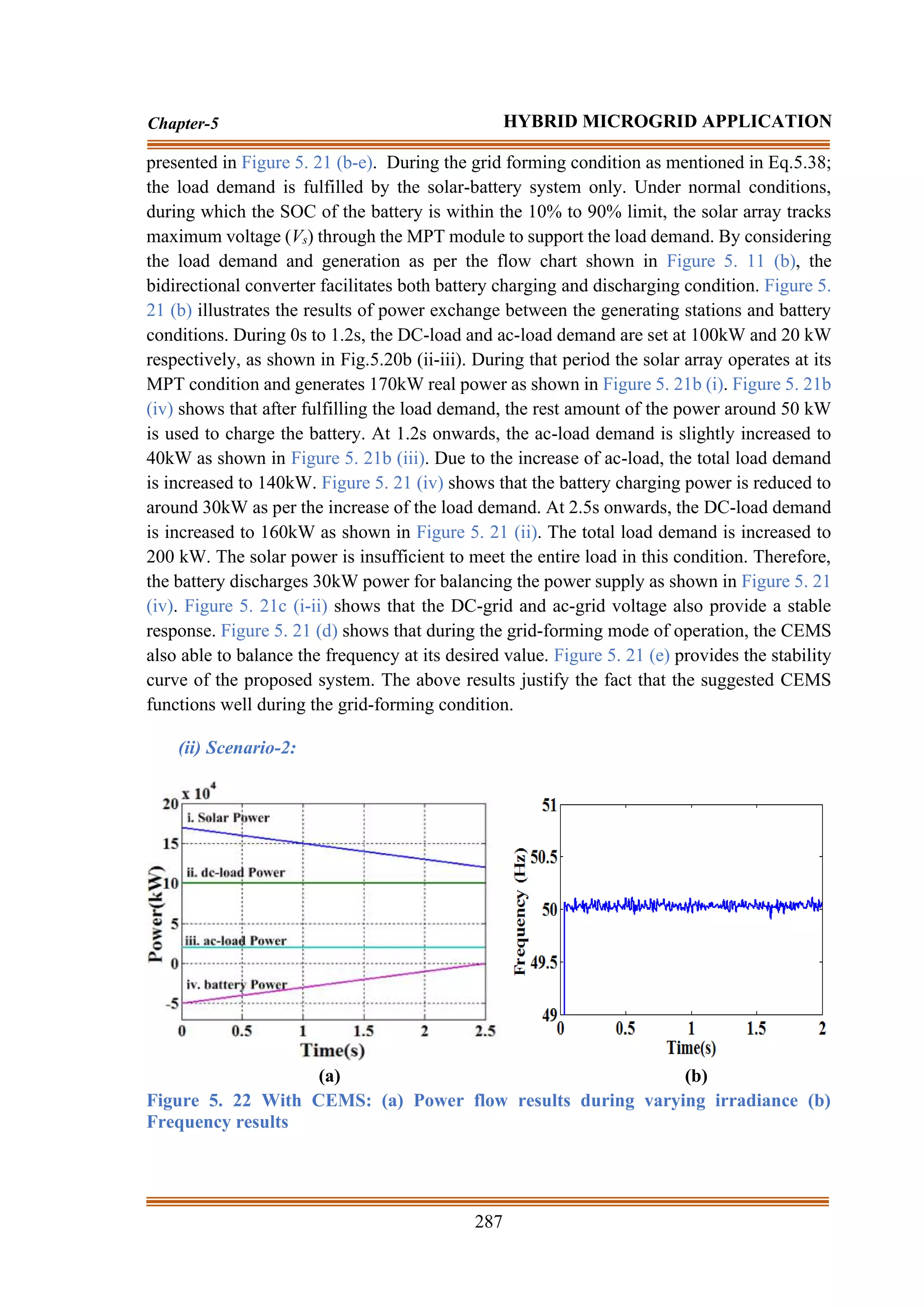

5.2.2.3 Result Analysis:

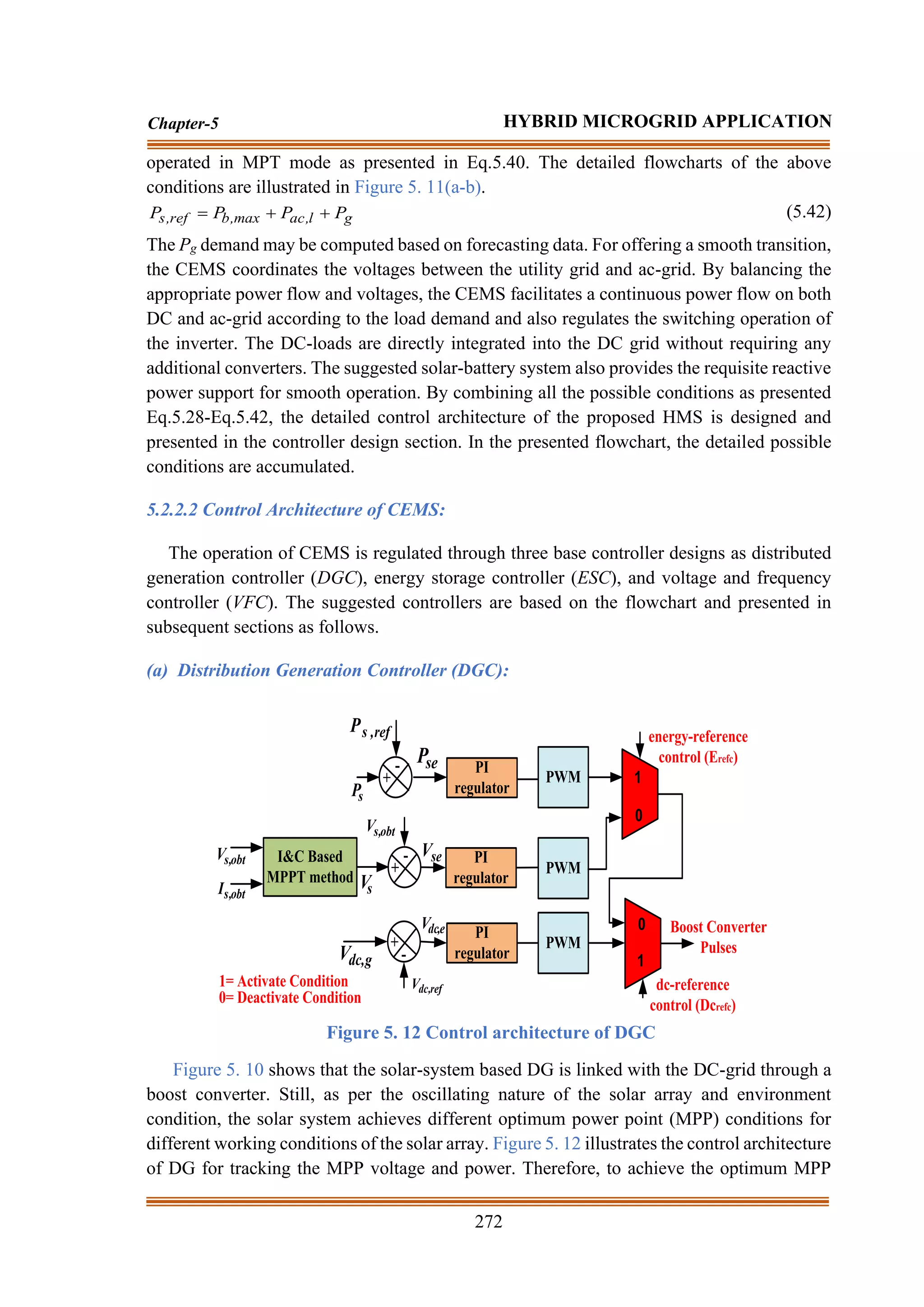

To examine the performance of the proposed HMS and CEMS, different case studies are

carried out through the MATLAB/ Simulink environment. The overall configuration of the

designed system model is shown in Figure 5. 10. The solar system is tested under a standard

testing condition (STC) of irradiance =1000W/m2

and temperature = C

25

. The size of the

nickel-cadmium (Ni-cd) characteristics-based battery is chosen according to the IEEE 1562-

2007 standard [322]. The battery is chosen such that it can facilitate 5 days of independent

operation for 150kW load capacity under changing environmental conditions. The

undertaken simulated parameters of the proposed HMS are presented in Chapter-5

Appendix-1 (Table.A.6). The suggested CEMS regulates the system performance and

operates the data according to the requirement as shown in Figure 5. 11 (a-b). As per the

situation raised, CEMS regulates the switches of the inverter and converter to facilitate the

system operation for both grid-following and grid-forming mode as illustrated in Figure 5.

11 (a-b) flowchart. The proposed approach provides a complete solution to maintain the

continuity of power flow as per the requirement. The designed HMS model is tested by using

CEMS and without CEMS. The obtained results are compared with each other to show the

existence of proposed CEMS over without CEMS.

(a) Grid-following Operating Condition:

(i) Scenario-1:

This scenario is studied for the normal grid-following condition when the battery is used to

regulate the power within the SOC limit (10% < SOC< 90%) as illustrated in Figure 5. 11

(a). According to the proposed DGC, the maximum voltage reference (Vs) and maximum

power (Pmax) are tracked by using the I&C MPT algorithm. The DC-loads and ac-loads are

supplied from the DC-grid and ac-grid respectively. In this condition, the DC-load and ac-

load are set 50kW and 10kW respectively. To show the variability of the supervised control

strategy and BES working conditions, the grid demand is intentionally varying from 110kW-

85kW-70kW at a specific time interval. According to the ESC, the battery power is balanced

by absorbing and releasing the power as per the generation, load, and utility grid demand.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dr-211204045233/75/Robust-Active-Power-Filter-Controller-Design-for-Microgrid-and-Electric-Vehicle-Applications-part-2-73-2048.jpg)

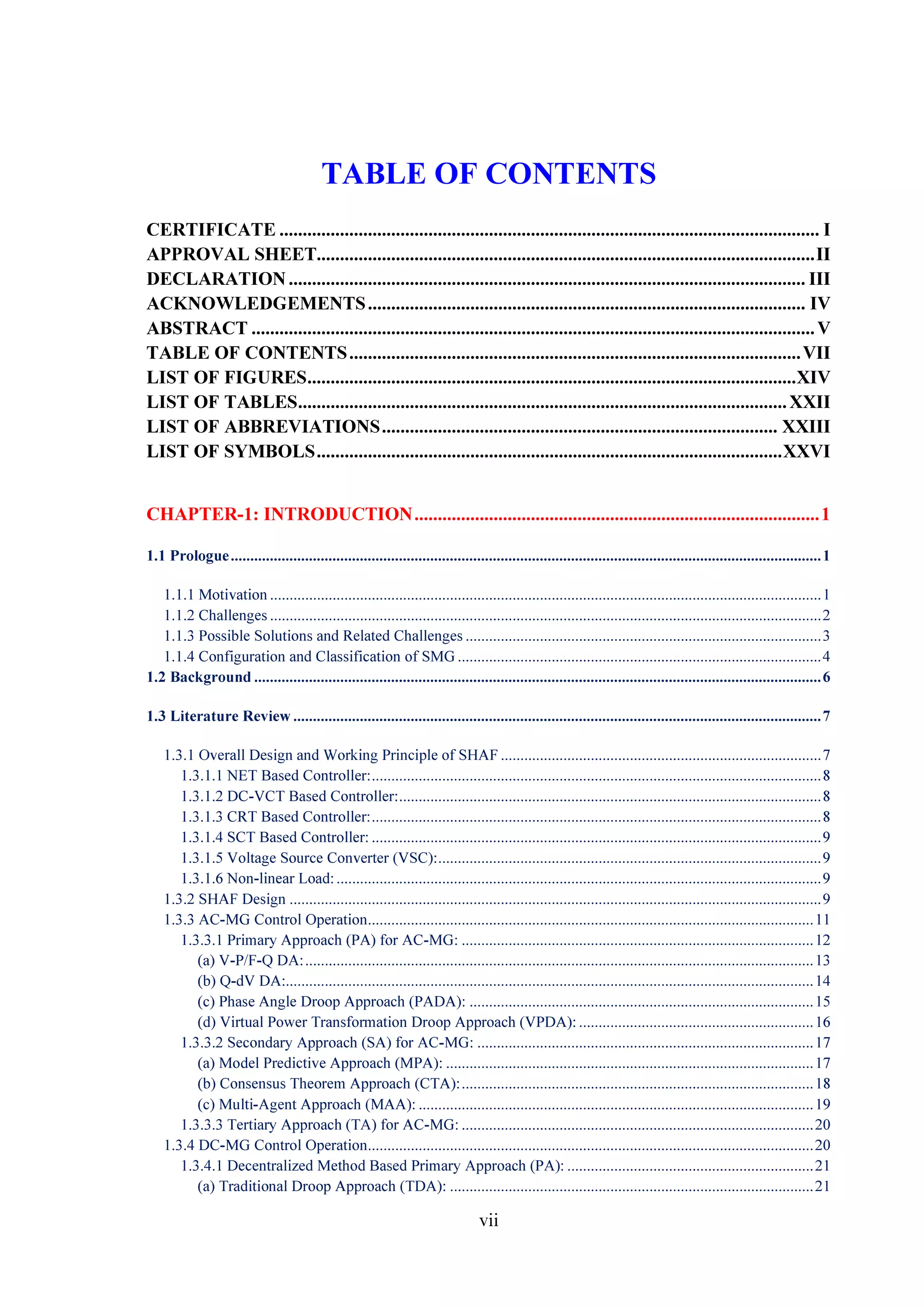

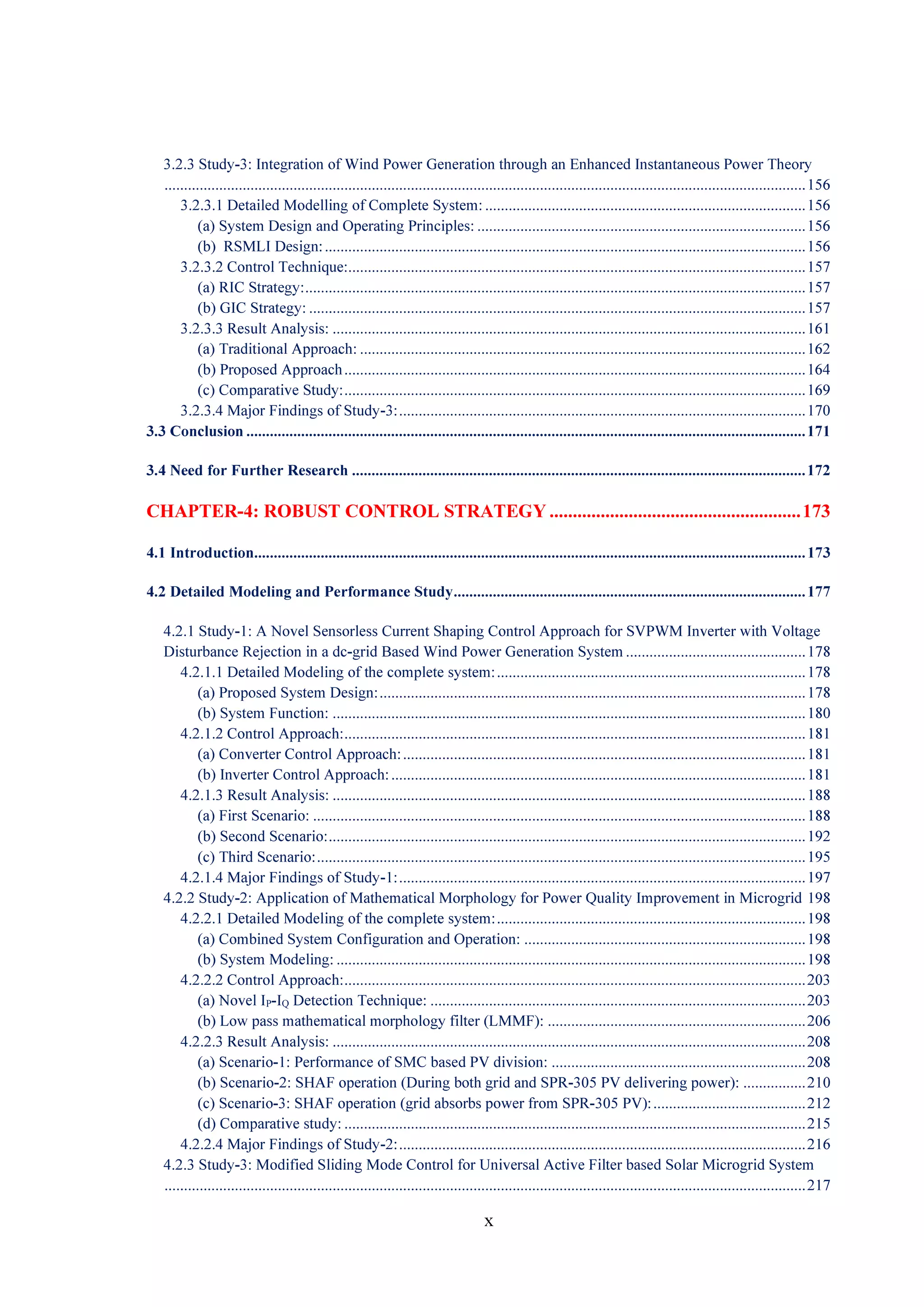

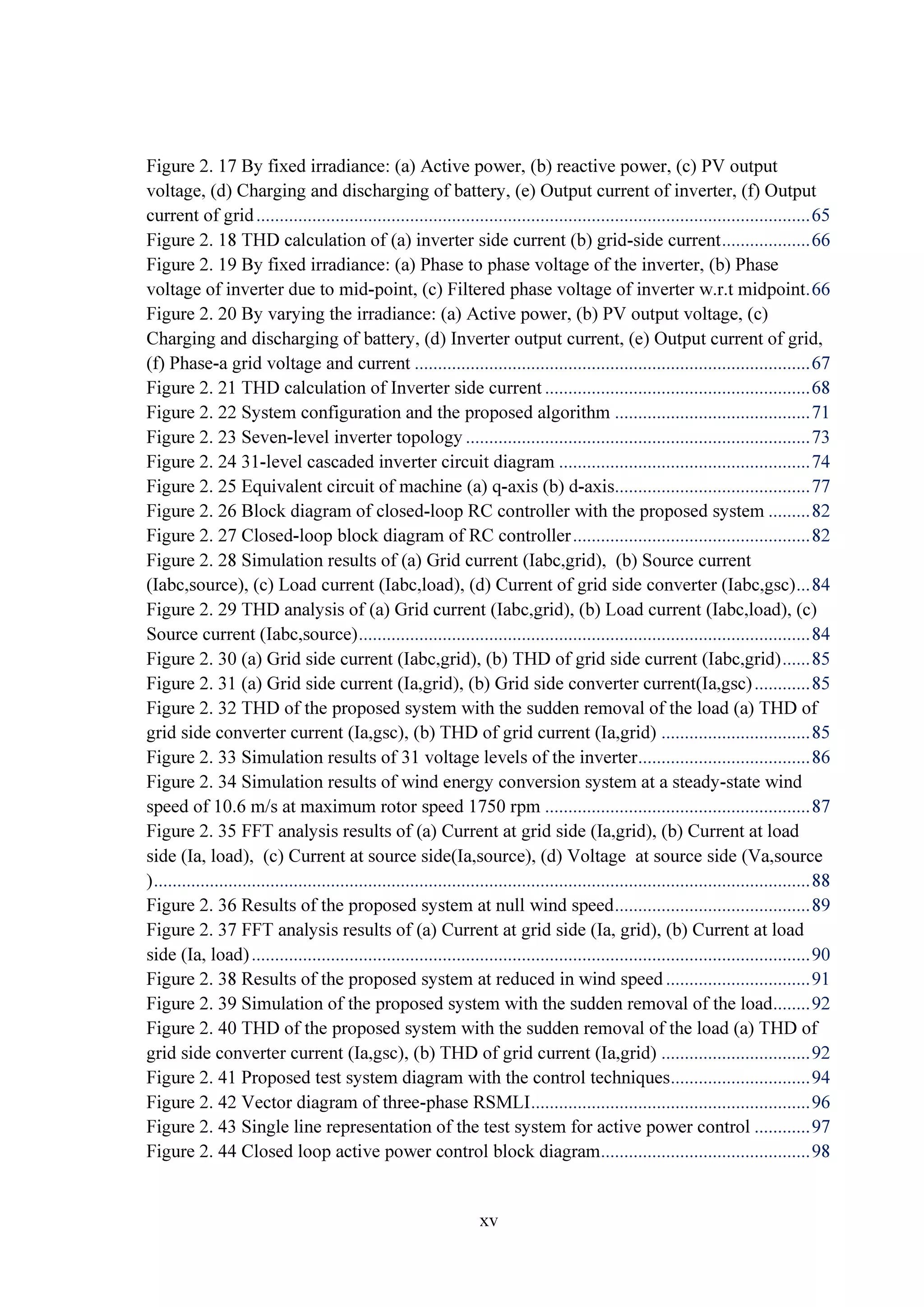

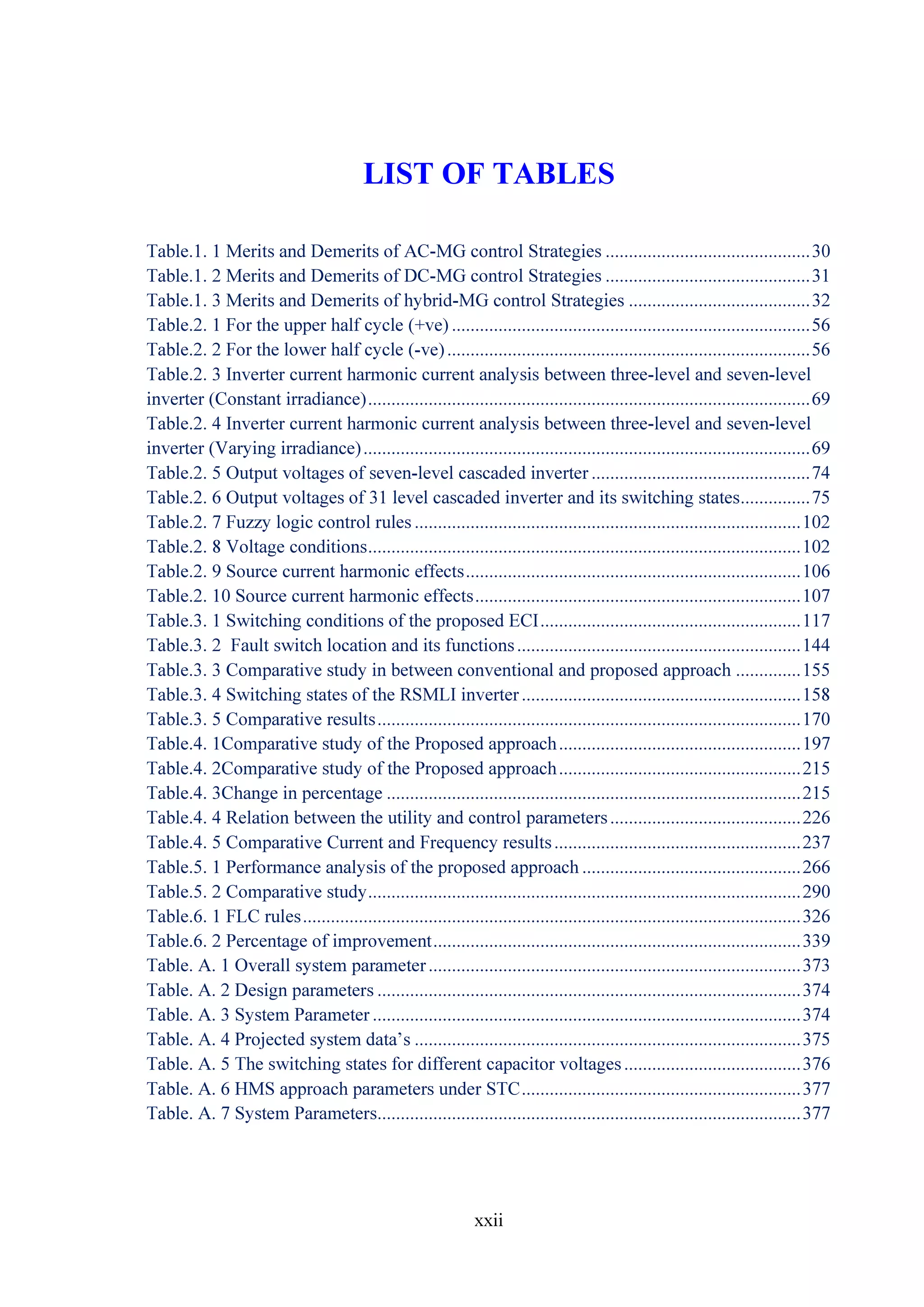

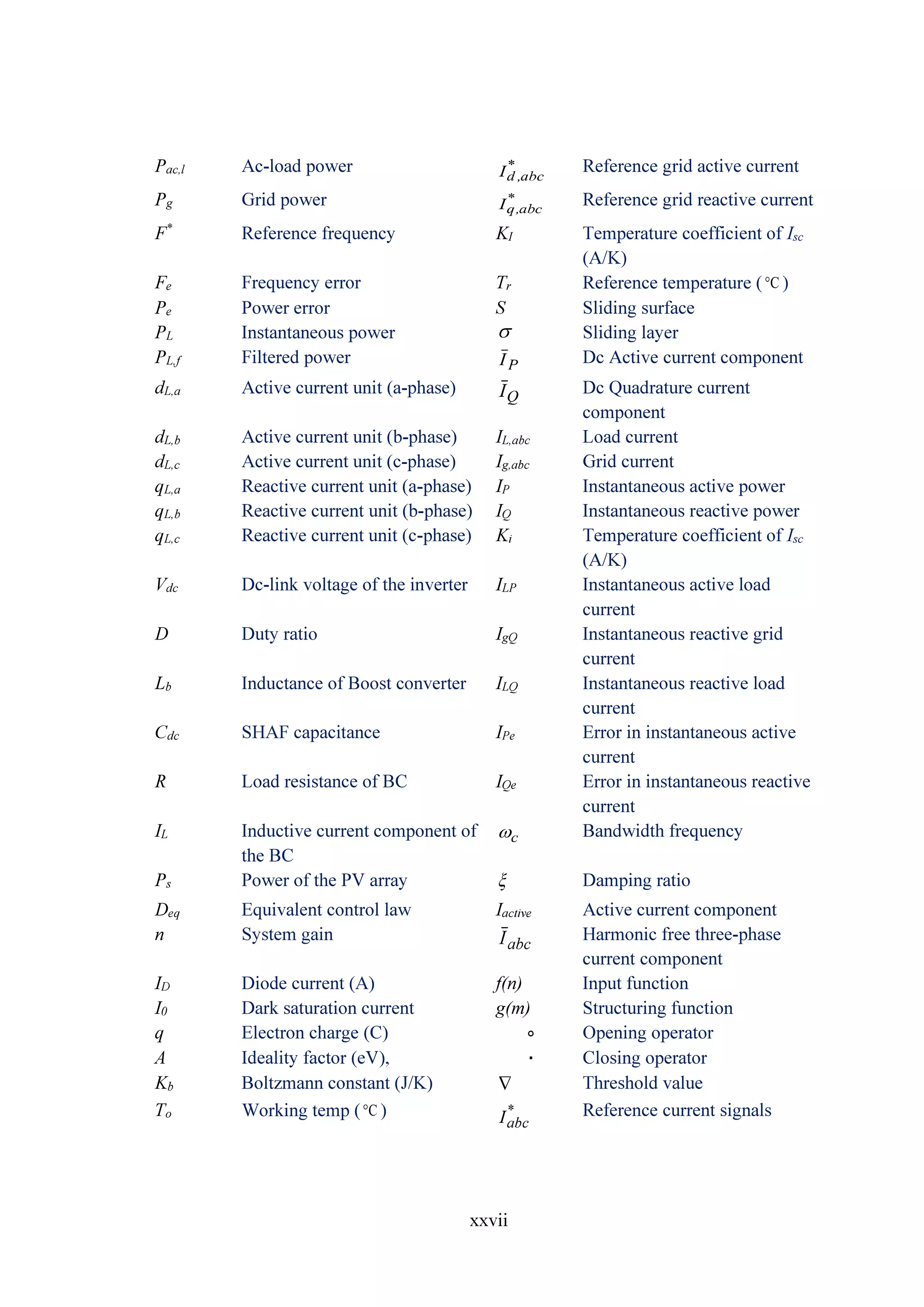

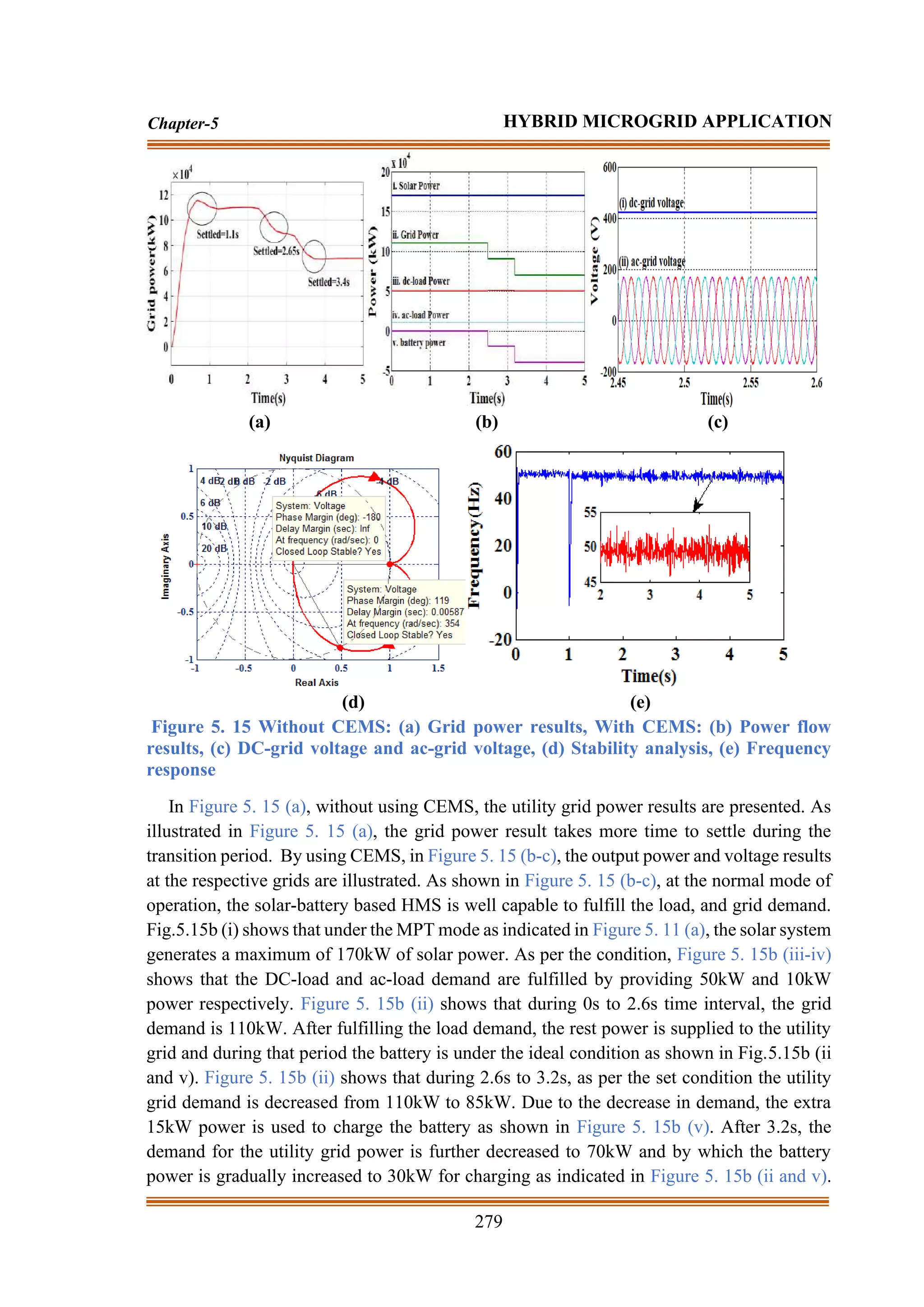

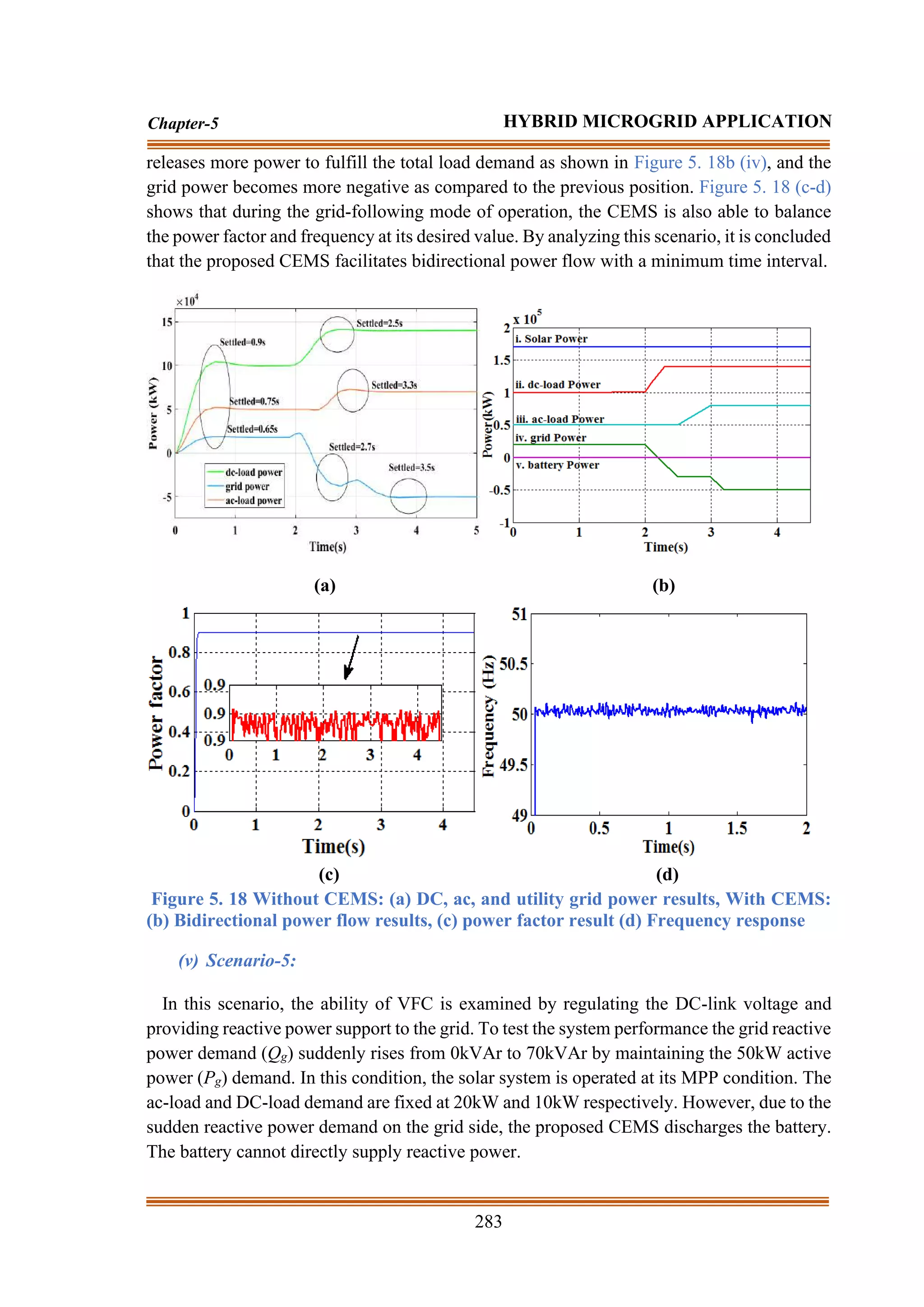

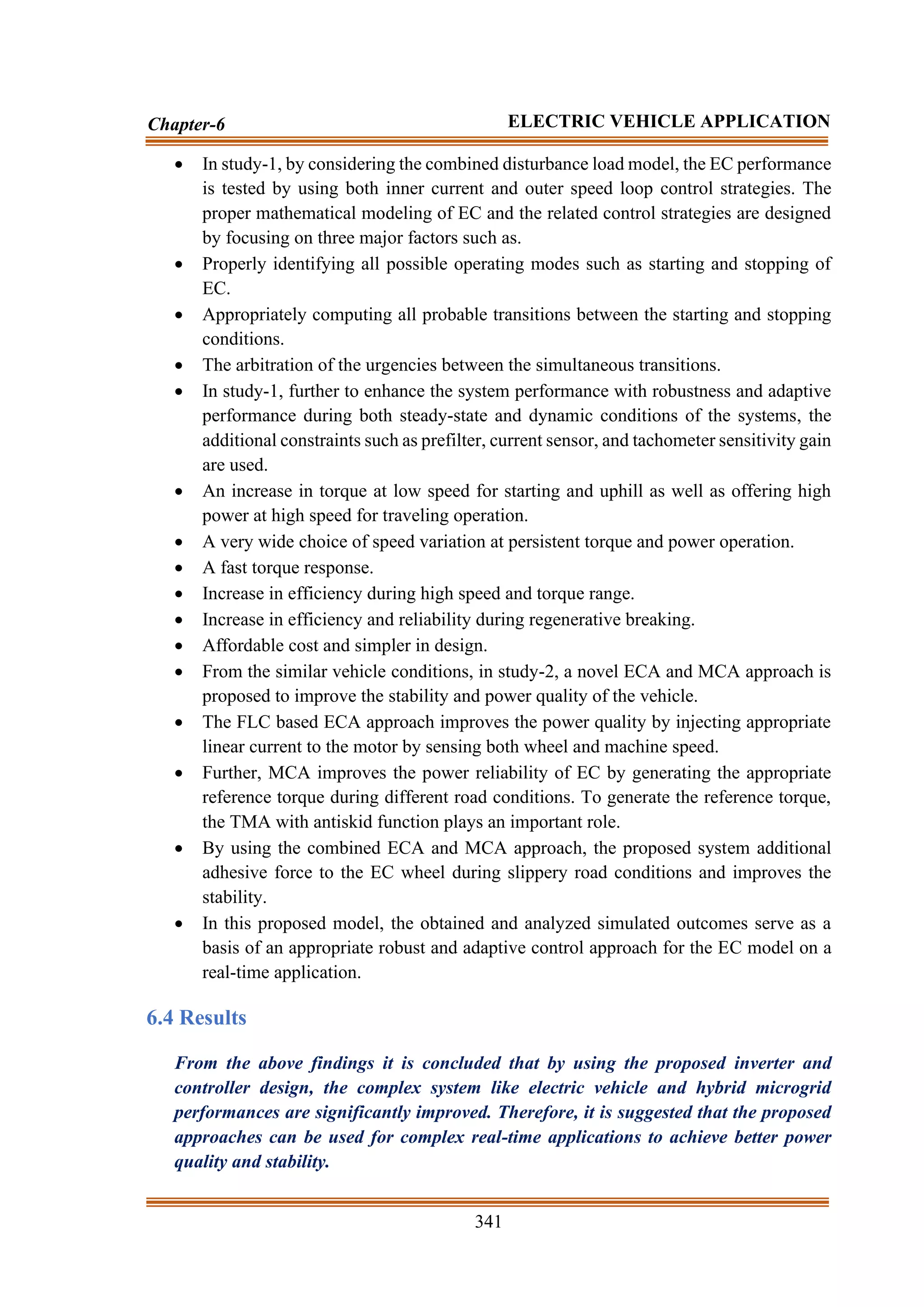

![290

Chapter-5 HYBRID MICROGRID APPLICATION

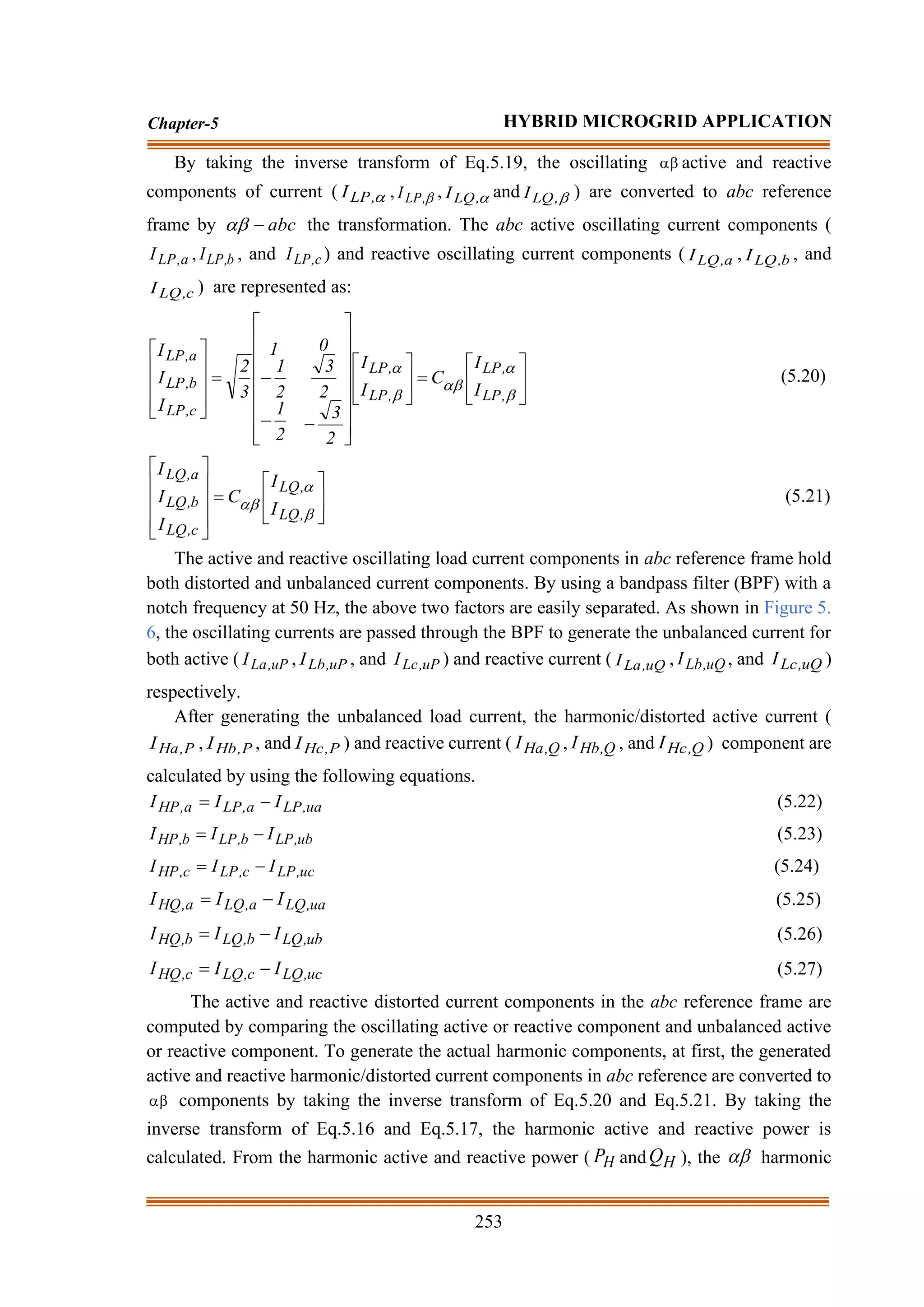

concluded that the proposed approach results have faster settled as compared to the

traditional approach results. Due to the faster settling responses, the system offers better

synchronization as compared to the traditional absence of CEMS. To show the proposed

approach effectiveness, a comparison between without CEMS and with CEMS based HMS

is presented in Table.5. 2. From Table.5. 2, it is clearly illustrated that the responses of the

proposed approach are a faster settling time according to IEEE-1541 and IEEE 1562-2007

standards [28]. From the results and comparative table, it is concluded that the proposed

HMS achieves better power quality and power reliability by producing linear results and

faster settling time during both normal and transient conditions.

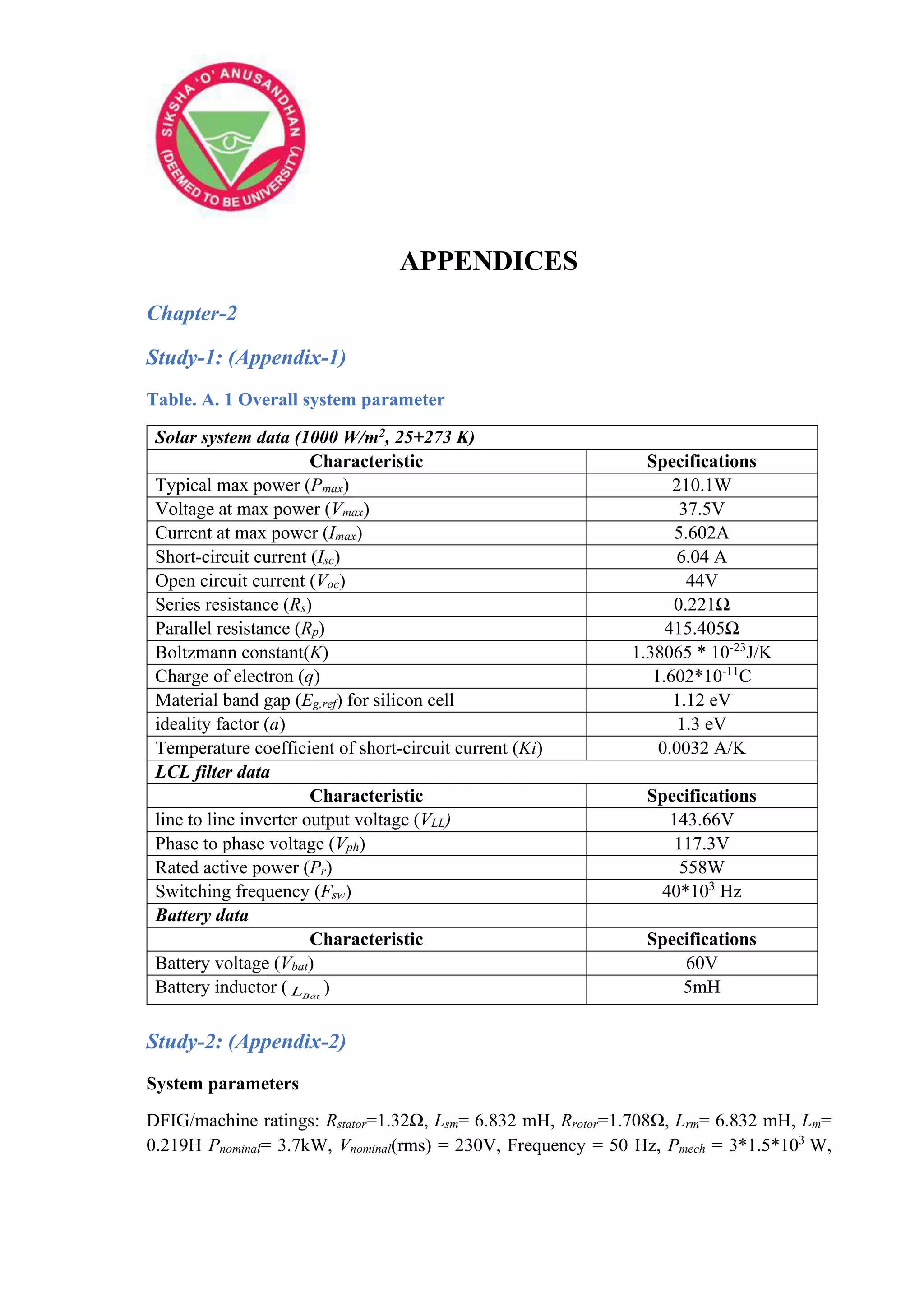

Table.5. 2 Comparative study

Grid following mode Without CEMS With CEMS

Duration Duration

Transition Condition Initial 2.5s 3.2s Initial 2.5s 3.2s

Scenario-1 Grid power 1.1s 2.65s 3.4s 0.1s 2.51s 3.22s

Duration Duration

Transition Condition Initial 2s 3s Initial 2s 3s

Scenario-2 Grid power 0.1s 2.75s 3.35s 0.1s 2.4s 3.2s

Battery power 0.9s 2.8s 3.5s 0.1s 2.4s 3.15s

Duration Duration

Transition Condition Initial 2s 3s Initial 2s 3s

Scenario-3 Solar power 0.82s 2.7s 3.25s 0.1s 2.1s 3.15s

Grid power 0.813s 2.62s 3.22s 0.1s 2.25s 3.16s

Duration Duration

Transition Condition Initial 2s 3s Initial 2s 3s

Scenario-4 Grid power 0.65s 2.7s 3.5s 0.1s 2.5s 3.2s

Transition Condition Duration=2.5s Duration=2.5s

ac-load power 3.3s 3s

Transition Condition Duration=2s Duration=2s

DC-load

power

2.5s 2.23s

Duration Duration

Transition Condition Initial 4s 6.2s Initial 4s 6.2s

Scenario-5 Battery power 0.98s 4.25s 6.5s 0.1s 4.05s 6.21s

Active power 1.1s - - - - -

Reactive

power

0.1s 4.5s 6.35s 0.1s 4.2s 6.23s

Grid forming mode Without CEMS With CEMS

Duration Duration

Transition Condition Initial 1.2s 2.5s Initial 1.2s 2.5s

Scenario-1 Battery power 0.75s 1.5s 2.9s 0.1s 1.21s 2.51s

Transition Condition Duration=2.5s Duration=2.5s

DC-load

power

2.75s 2.52s

Transition Condition Duration=1.2s Duration=1.2s

ac-load power 1.8s 1.56s](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dr-211204045233/75/Robust-Active-Power-Filter-Controller-Design-for-Microgrid-and-Electric-Vehicle-Applications-part-2-85-2048.jpg)

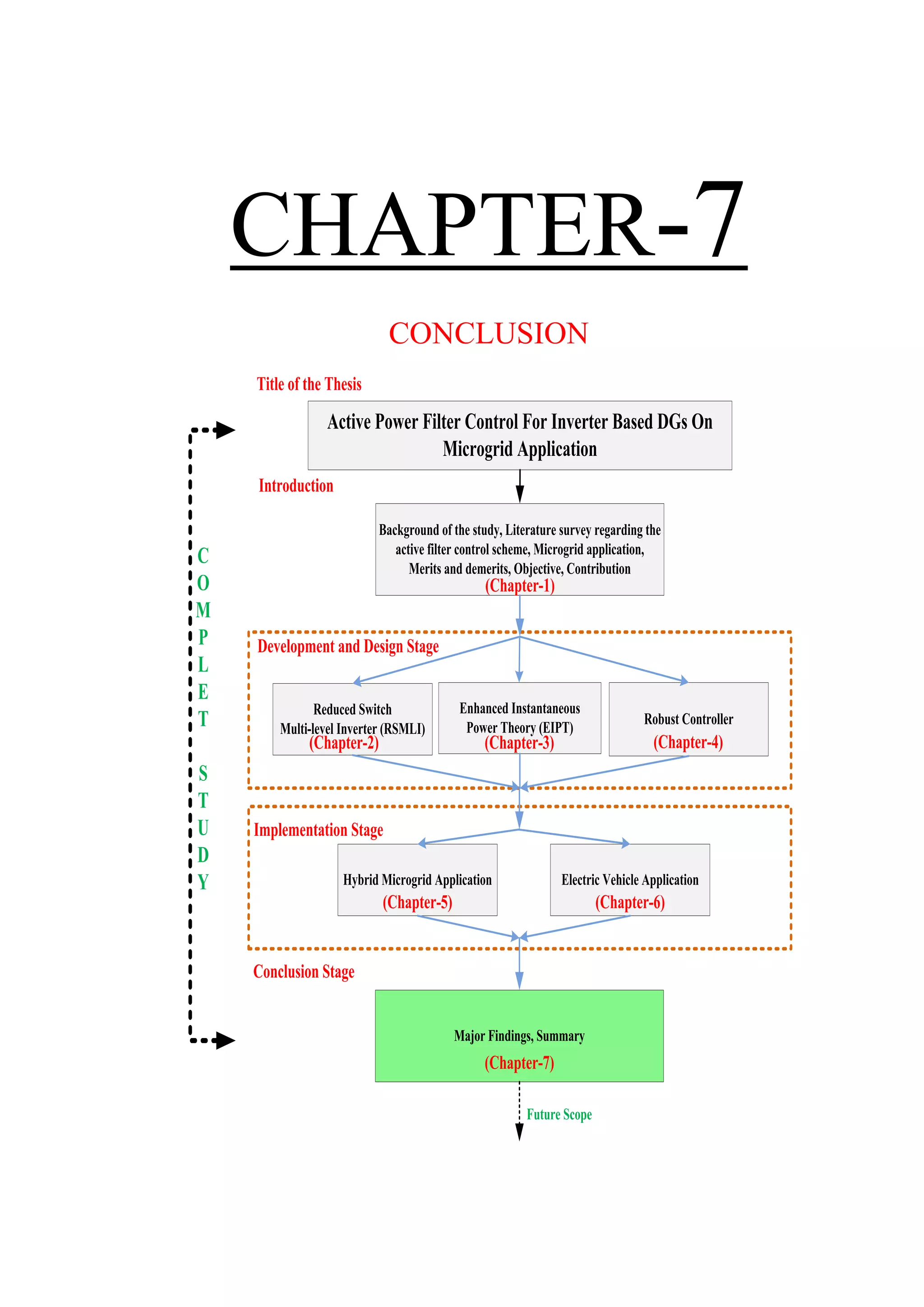

![Chapter-6

ELECTRIC VEHICLE APPLICATION

6.1 Introduction

Looking at the environmental condition and the awareness of energy conservation,

researchers are paying more attention to the design of zero-polluting ECs. Recently, the

improvement with regards to EC/Hybrid-EC modeling is gaining interest on an augmented

pace [323]. Particularly, the lesser weight ECs are becoming popular in many applications

like patrolling and smaller distance transportation cars. Lots of EC modeling techniques are

suggested to offer a larger driving range and linear operation [324]. Generally, the EC

modeling is designed by considering two subsystems like electric motors (EM) as a drive

system and the car platform as indicated in Fig.1. The main components of EC are battery

energy storage (BES) devices, central control structures, tachometer, and voltage source

converter (VSCs) that convert dc-ac power. To drive the EC wheel, single EM is used for

each of the wheels [325]. However, the increasing cost and complex modeling, [326] lose its

attraction during real-time applications. By viewing the simplicity and easier control action,

dc EM is popularly selected for the traction of ECs [327]. In addition to that dc-motors also

supply high starting torque. Therefore, for availing a robust/lighter model with high

efficiency, and reduced cost EC, it is necessary to derive an appropriate mathematical model

of EC and EM for both steady and dynamic state operations.

Simple EC design leads to a simple control strategy that decreases the overall cost of

the vehicle. However, the development of the simple EC model is difficult because of the

uncertainty and non-linearity present in the environmental, wheel, and road conditions [328-

212]. Mostly, the disturbances are categorized into two types such as (1) parametric non-

linearities and (2) inner/outer disturbances. The first type of disturbance is raised due to the

lack of appropriate information regarding the EC modeling, friction modeling, and parameter

fault conditions, and the second type of disturbance is generated due to the unidentified

effects of existing physical constraints in the environment [329-330]. Therefore, there is a

necessity to design improved mathematical modeling of EC by considering the possible real-

time disturbances.

Normally, the ECs are recognized as ‘MCMM’ [331-332]. Therefore, there is a

necessity to develop a coordinated electrical and mechanical control approach for facilitating

satisfactory driving performance and smoother operation by optimally consuming power](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dr-211204045233/75/Robust-Active-Power-Filter-Controller-Design-for-Microgrid-and-Electric-Vehicle-Applications-part-2-90-2048.jpg)

![294

Chapter-6 ELECTRIC VEHICLE APPLICATION

[287]. Due to the tremendous growth of the microprocessors/microchips, it is easier to

develop the complex controller for MCMM based EC operation [333]. By using the above

controller, the stability and safety of the EC are significantly improved during different state

conditions [334]. Many researchers have proposed different adaptive techniques to overcome

the first type of problems [335]. However, during the non-linear and disturbance conditions,

the adaptive techniques lag their performance by increasing the torque ripples. As a solution,

different adaptive techniques are proposed to overcome the nonlinearity present in the

environment by increasing the stability and safety of the system [336-338]. In [223], direct

torque control (DTC) for the synchronous machine has gained a lot of attention in the field

of industrial drive application specifically to EC operation. However, due to the excess use

of the hysteresis band controller, the DTC scheme lags their performance by increasing the

torque ripple during the transient condition. In [339], a robust control approach is proposed

to obtain faster ripple-free torque action for eliminating the problems related to the

mechanical transmission of the electrical traction chain. In [340], a novel control technique

for the synchronous machine-based EC wheel is proposed to increase the dynamic DTC

performance and decrease the ripple torque by using a model predictive direct torque control

(MPDTC) with an enhanced cost function during steady-state operation. However, for

MCMS based EC operation, the predictive torque control is not providing a suitable solution

during dynamic state conditions like slippery road conditions. To reduce the ripple torque

problem and disturbance conditions, adaptive feedback linearization approaches are

proposed for guessing an approximate disturbance component [341]. However, the offline

non-linearity identification control techniques are not well suited for MCMS because the

disturbances change over time. Therefore, there is a necessity to develop a suitable online

adaptation technique for generating lesser ripples torque components.

In addition to the above, for improving the EC stability and safety condition, it is

necessary to regulate the electric machines according to the road and wheel position. To

achieve this, there is a requirement for better synchronization between ECA and MCA. For

achieving better synchronization and full utilization of the electric motor application, a

control law is required to formulate. By tracking the appropriate EC speed, the electrical

torque, wheel torque, road condition, and operating time, the control law for the MCMS

system is proposed for accelerating and deaccelerating the EC [342]. For improving the

stability and safety of the EC during slippery road conditions, the formulation of a suitable

control is considered as one of the major aspects of the study.

Furthermore, recently in automotive applications, there is a novel active control

technique used to improvise safety and provide antiskid operation during the EC riding and

handling conditions. Special control techniques are developed and applied for different parts

of the EC applications [343]. One of the special techniques like the traction control technique

(TCA) is a very classic and unique technique used for improving the EC stability and

reliability problem [154]. TCA is a control approach which prevents the skidding of wheels

during slippery road condition [286]. By doing a technical literature survey, it is found that

TCA is alternatively termed as an acceleration slip regulation (ASR) [344]. To design TCA,](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dr-211204045233/75/Robust-Active-Power-Filter-Controller-Design-for-Microgrid-and-Electric-Vehicle-Applications-part-2-91-2048.jpg)

![295

Chapter-6 ELECTRIC VEHICLE APPLICATION

different control schemes are suggested by many researchers, and few of them are discussed

below.

In [334], a Fuzzy-PI based ASR scheme for appropriate estimation of wheel torque is

proposed. However, the above-proposed technique lags their performance and stability due

to the absence of the antiskid function. As a solution in [345], to improve the stability and

vehicle safety, an FLC based antiskid control technique is suggested. In addition to that, a

sliding mode control-based wheel slip controller is suggested for MCMM [346]. A model

predictive controller is suggested for wheel slip control for four in-wheel machines of EC

[311]. However, the above-proposed technique lags their tracking performance due to the

use of a predictive controller, low pass filters, complex control structures, and excess use of

the hysteresis band controller. Therefore, there is a necessity to develop a simple and robust

controller for providing appropriate breaking operations during slippery road conditions.

Looking at the above problems, this chapter is divided into two individual studies as

Study-1, and Study-2, for the appropriate design and control of the electric car through an

appropriate inverter model and novel control strategy. By using the developed RSMLI and

its control strategy, the proposed electric vehicle is designed and its performances are also

studied at different state conditions. In addition to that, the PQ and PR of the proposed

systems are also studied during external disturbance conditions. The main contribution to the

individual studies is presented as follows.

Study-1: A Novel Speed and Current Control Approach for Dynamic Electric

Car Modelling

Major contribution:

• For designing a lighter weight and reduced cost electric car (EC) system, the detailed

mathematical modeling of EC and electric machine (EM) are developed.

• By viewing the inner and outer uncertainty/disturbances, two load models are

designed. Due to the load model, the system gets an appropriate idea about the real

uncertainty conditions.

• Different subsystem transfer functions of EC components such as the battery,

inverter, and motor model are developed to obtain an appropriate idea of the EC

model.

• Improved control models are designed by using different geometrical methods by

using the sensitivity gain of both current sensors and tachometer.

• For offering linear output and linear EC operation, a combined PI control-based outer

speed and inner current control approach is suggested.

• Looking at the real-time conditions, different EC models are suggested for different

operations and applications.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dr-211204045233/75/Robust-Active-Power-Filter-Controller-Design-for-Microgrid-and-Electric-Vehicle-Applications-part-2-92-2048.jpg)

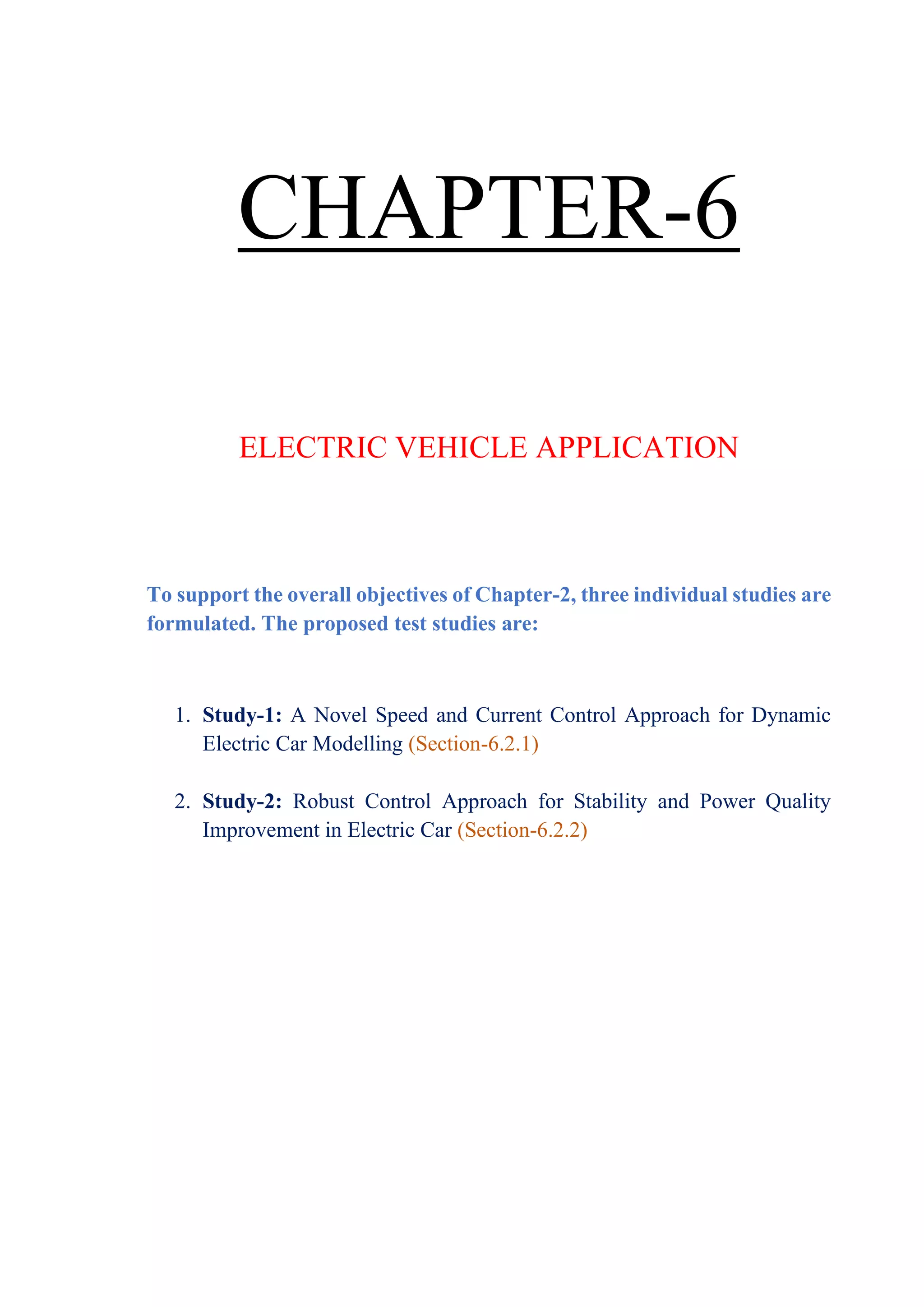

![297

Chapter-6 ELECTRIC VEHICLE APPLICATION

appropriate EC model carefully. By computing the appropriate torque and power model, the

detailed dynamic modeling of respective EM and EC is presented below.

(a) Dynamic Modelling of Electric Motor (DMEM):

The main role of an electric motor (EM) is to provide necessary force for the EC speed

regulation as indicated in Figure 6. 2. Therefore, appropriate mathematical modeling of the

EM is much more important for the EC operation. To assure a suitable speed-up time, the

driving EM necessitates an excess torque output under slower speed and lesser torque output

under higher speed operation. In addition to that, to achieve a higher speed time, driving EM

is necessary to attain a certain power output at high-speed operation [347]. The appropriate

dynamic equation of EM is obtained by combining Newton’s law and Kirchhoff’s law.

Mechanical

Transmission

Mechanical

Coupling

Battery

Charger

Battery Charging point

Controller

Electric

Drivers

DC-AC

Power

inverter

Tachometer

Battery

Front Wheel

AC Motor

Overall diagram of

electric vehicle

Control architecture

of electric vehicle

Figure 6. 1 Complete system architecture of EC

The basic mathematical equations of any EM are presented as follows.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dr-211204045233/75/Robust-Active-Power-Filter-Controller-Design-for-Microgrid-and-Electric-Vehicle-Applications-part-2-94-2048.jpg)

![301

Chapter-6 ELECTRIC VEHICLE APPLICATION

n

r

V M

=

(6.25)

Applying Eq.6.25 in Eq.6.23, the JL becomes,

2

2

T

L

n

r

M

J = (6.26)

By considering the above-discussed equations, the equivalent EC open-loop transfer function

( )

s

(

Gs ) can be presented as

b

t

T

T

a

a

t

in

M

s

K

K

)

B

sJ

)(

R

sL

(

n

K

)

s

(

V

)

s

(

)

s

(

G

+

+

+

=

=

(6.27)

By considering the armature voltage input (Vin), the output voltage of the tachometer (Vtach)

with the corresponding load torque (TL), the EC open-loop transfer function ( )

s

(

Go ) can be

presented as.

b

t

a

a

T

T

a

a

tach

t

in

M

tach

in

o

o

K

K

T

)

R

sL

(

)

B

sJ

)(

R

sL

(

K

K

)

s

(

V

)

s

(

K

)

s

(

V

)

s

(

V

)

s

(

G

+

+

+

+

+

=

=

=

(6.28)

where T is denoted as the disturbance torque including the Coulomb friction (TF). To track

the actual speed of the EC and fed it back to the control system, a tachometer is used in EC.

The tachometer dynamics and the corresponding transfer function is illustrated in Eq.6.29.

To achieve a linear speed of EC of 23m/s, the tachometer constant (Ktach) is selected as 0.4696

[28].

)

s

(

K

)

s

(

V

dt

)

t

(

d

K

)

t

(

V M

tach

o

M

tach

o

=

= (6.29)

where o

V is denoted as the system output voltage.

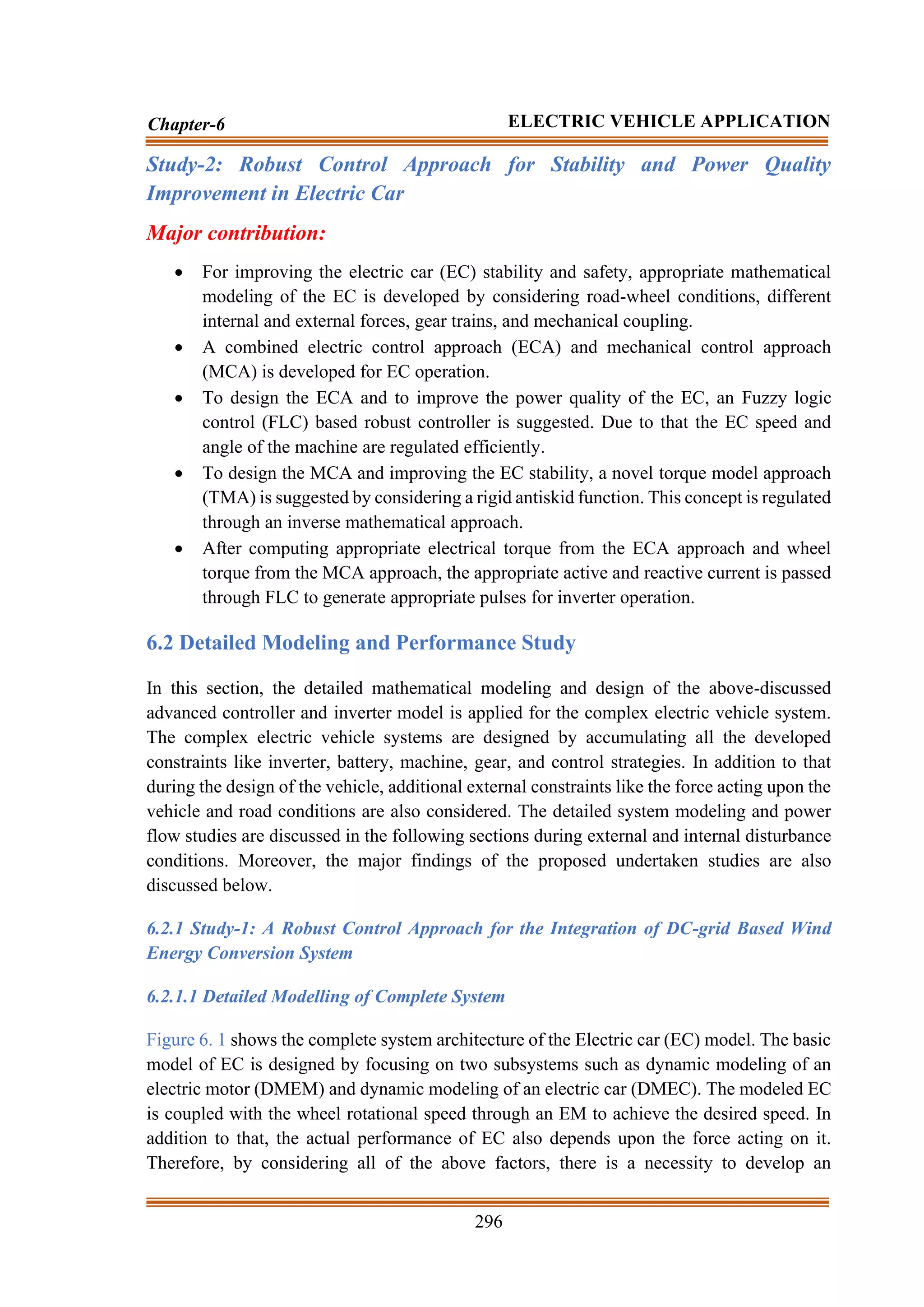

(b) Dynamic Modelling of Electric Car (DMEC):

Force

Resistance

Rolling

FR =

Velocity

Vehicle

VEV =

Force

Wind

FW =

Vehicle

the

of

Force

nal

Gravitatio

Fg =

Force

Inertial

FI =

Force

Traction

FT =

Force

Normal

FN =

angle

driving

=

Figure 6. 3 Free body diagram of EC with different forces

Figure 6. 3 illustrates the overall motion diagram of the electric car by showing different

forces. By balancing the magneto and electromotive force (MMF and EMF) of electric motor

and operating resistive forces [28], the speed of the EC is decided. To derive an accurate](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dr-211204045233/75/Robust-Active-Power-Filter-Controller-Design-for-Microgrid-and-Electric-Vehicle-Applications-part-2-98-2048.jpg)

![302

Chapter-6 ELECTRIC VEHICLE APPLICATION

DMEC, it is much more important to track the dynamics between the road, wheel condition

and the acting forces such as wind force (FW), inertia force (FI), rolling force (FR), traction

force (FT), and normal force (FN) upon the EC respectively. The EC torque disturbance is the

resultant torque produced by all the resistive forces acting upon the EC as presented below.

acc

_

a

W

R

N

g

I

F

C

2

W

C

F

2

W

C

f

d

W

C

F

r

F

C

C

F

C

F

C

C

T

V

r

J

M

)

V

V

(

A

C

2

1

)

V

V

(

sign

C

.

)

cos(

.

g

.

M

)

V

(

sign

)

sin(

.

g

.

M

V

M

F

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

=

(6.30)

2

a

acc

_

a

r

G

I

F

= (6.31)

where MC is the mass of the car (kg), VC is the velocity of EC (m/s), C

V

is the acceleration

of EC (m/s2

), g is the gravitational force on EC (m/s2

), is the driving angle of EC (rad), Cr

is the rolling coefficient of EC, is the density of air at 20°𝐶 , Cd is the drag coefficient of

EC, Af is the front area of EC, VW is the wind velocity (m/s), JW is the wheel moment of

inertia of EC, r is the radius of the wheel, G is the gear ratio, Ia is the armature current of the

motor, and Fa_acc is the angular acceleration force.

After computing the possible force acting on the EC model, it is necessary to design the

battery model. The battery is used only to provide the supply voltage for the EC operation.

Before computing the battery capacity of the EC, it is necessary to estimate the total

requirement of electrical energy for the EC operation. The power demand is measured in kW

and the power is used to regulate the speed of the EC. The electric power (Pe) is computed

by multiplying the total traction force (FT) and VC, and represented as follows.

C

T

C

e V

F

V

F

P

=

= (6.32)

The battery is the key element for the EC applications. In recent times, many different types

of battery like lead-acid, nickel hydride, and lithium-ion, etc., are used for different purposes

[28]. However, for real-time application point of view, lithium ion-based battery storage

device is selected due to relatively increase in specific energy and power [2-4].

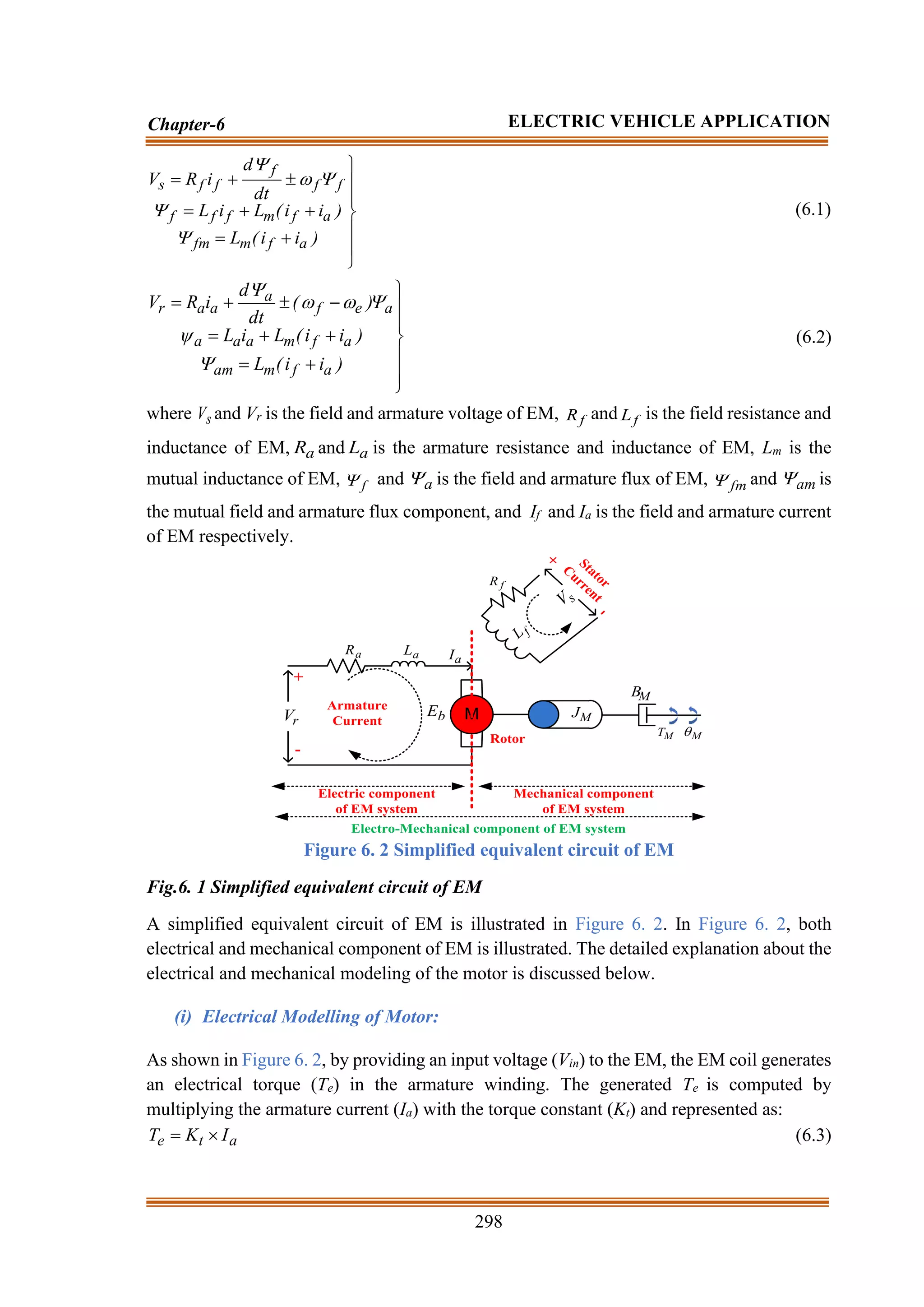

(c) Battery Electric Model:

The equivalent model of the battery is illustrated in Figure 6. 4. As illustrated in Figure 6. 4,

the equivalent battery model is designed by using internal voltage source (Vbi), battery

voltage (Vb), charging and discharging diode (Dbc and Dbd), and charging and discharging

resistance (Rbc, and Rbd) respectively. Db is known as the forward diode of battery and Ib is](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dr-211204045233/75/Robust-Active-Power-Filter-Controller-Design-for-Microgrid-and-Electric-Vehicle-Applications-part-2-99-2048.jpg)

![303

Chapter-6 ELECTRIC VEHICLE APPLICATION

known as the obtained battery current. The two diodes are generally ideal and only used to

facilitate both charging and discharging operations. The charging currents are denoted as ‘+’

sign and discharging currents are denoted as ‘-’ sign. The rating of Vbi, Rbd, and Rbc depends

upon the depth of battery discharge capability. As indicated in Figure 6. 4 equivalent circuit,

Vb is computed as follows.

−

−

=

0

I

R

V

0

I

R

V

V

b

bc

bi

b

bd

bi

b (6.33)

Internal

Battery

Voltage

Battery

Voltage

+

-

bd

R

bd

D

bc

D bc

R

bi

V

b

V

b

D

b

I

Figure 6. 4 Equivalent battery model

After generating the necessary electric power from the battery (Pe= VC*I) and power

available in the wheel of the EC (Pw), the driving angle ( ) of the EC is computed as follows.

C

C

e

w

V

M

P

P

−

=

(6.34)

After the successful modeling of the battery and DMEC, to get a more accurate precision

about the disturbance force (FD) acting on the EC, some other factors are also taken into

consideration. By viewing the accuracy demand of the EC, different constraints like total

driving resistance force (Fdr) and EC dynamics are considered. For a smooth acceleration of

the EC, the electric motor of the EC is necessary to overcome the Fdr. The modeling of the

EC dynamics is simplified in [286 ,347-348] and the corresponding equations are presented

below. The detailed explanation of the following equations is presented in [311].

2

C

W

d

f

r

C

C

w

D )

V

V

(

r

C

A

2

1

grC

M

)

sin(

g

M

R

)

t

(

F +

+

+

=

(6.35)

r

C

C

2

D C

)

sin(

gr

M

2

1

dt

d

M

r

2

1

)

t

(

T

+

+

= (6.36)

r

C

d

f

2

C

W

C

C

D grC

M

C

A

))

t

(

V

)

t

(

V

(

2

1

)

t

(

V

M

)

t

(

F +

+

+

=

(6.37)

)

cos(

gC

M

C

A

))

t

(

V

)

t

(

V

)(

sin(

g

M

2

1

a

K

M

)

t

(

F r

C

d

f

2

C

W

C

m

C

D

+

+

+

= (6.38)

where Rw is the wheel resistance, Km is the equilibrium constant, and ‘a’ is the acceleration

constant of the EC. Based on all the derived dynamic equations as presented in Eq.6.30,

Eq.6.35, Eq.6.36, Eq.6.37, and Eq.6.38, two load models are derived and presented in Figure

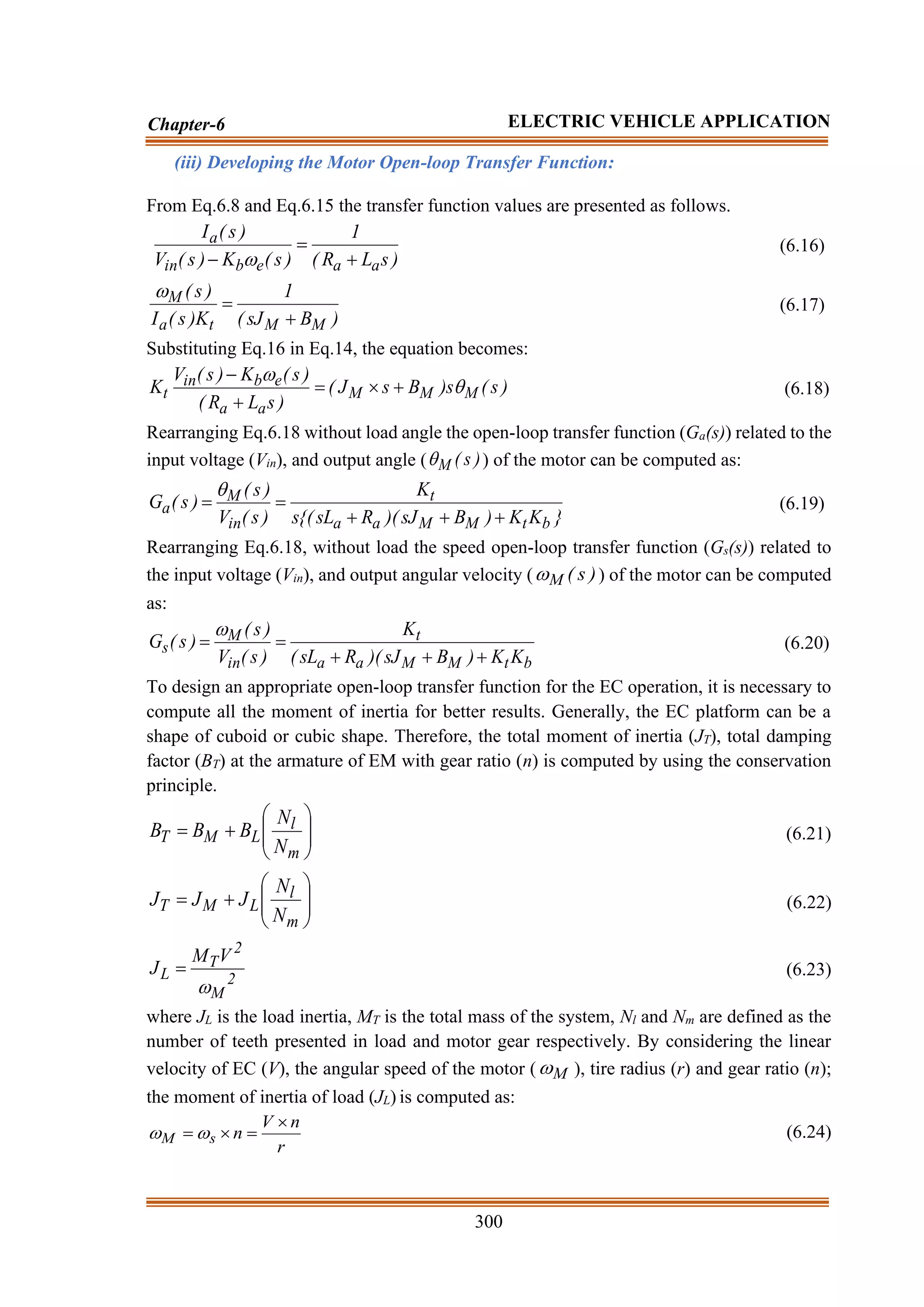

6. 5 (a) and Figure 6. 5 (b) respectively. To meet the accuracy level, all the related parameters](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dr-211204045233/75/Robust-Active-Power-Filter-Controller-Design-for-Microgrid-and-Electric-Vehicle-Applications-part-2-100-2048.jpg)

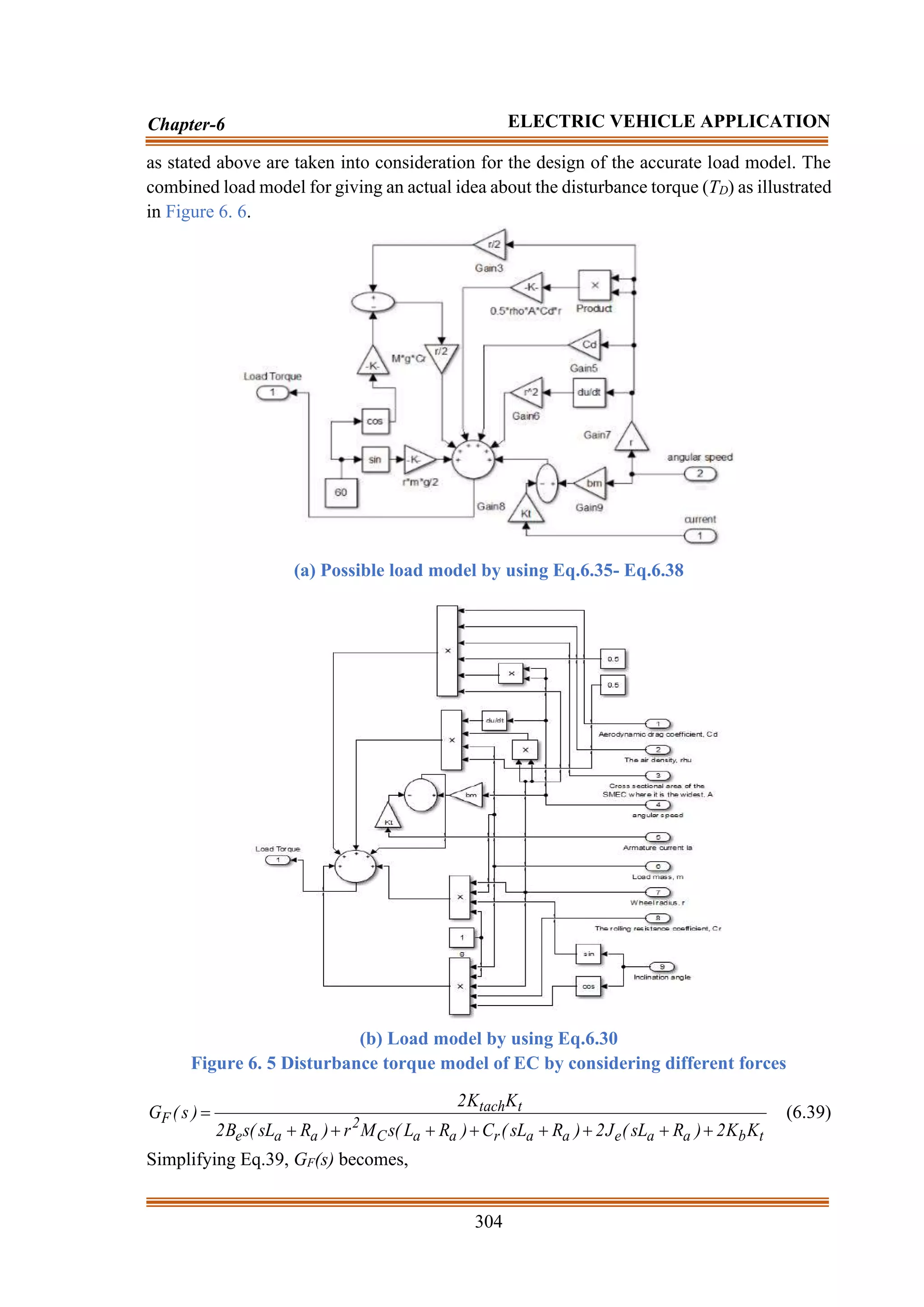

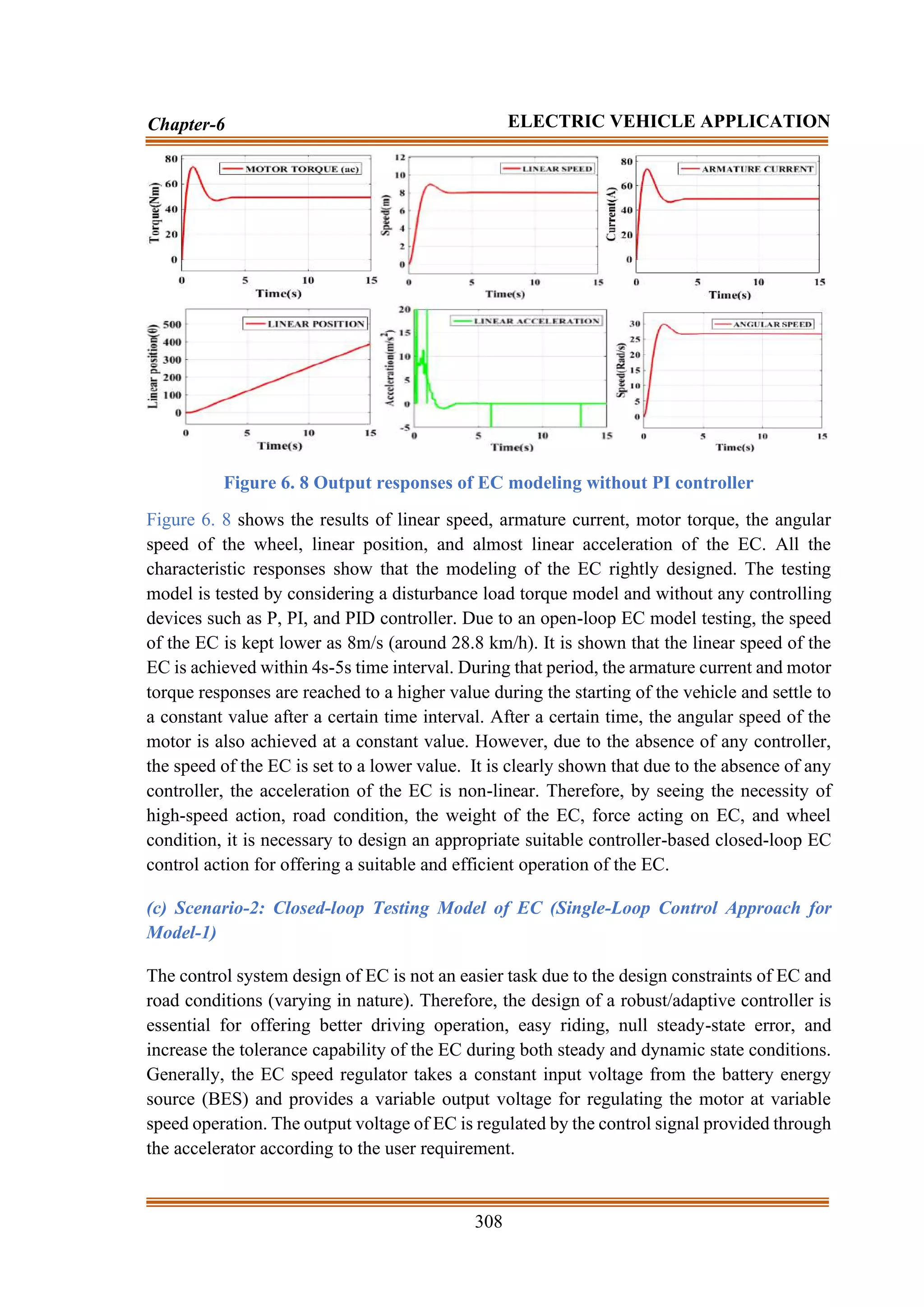

![310

Chapter-6 ELECTRIC VEHICLE APPLICATION

Due to the voltage regulation, the motor speed, as well as EC speed is regulated [349]. During

the operation of the EC accelerator, the battery discharges a specific amount of current to the

EM for achieving the required EC speed. In addition to that, the car sensors sense the actual

speed of the EC and send back it to the controller for offering a closed-loop control action.

As the battery supplies DC voltage and current, inverter plays an important role in dc-ac

voltage and current conversion for EM action. For appropriate voltage regulation, the inverter

switches are necessary to operate through the pulse width modulation (PWM) technique. By

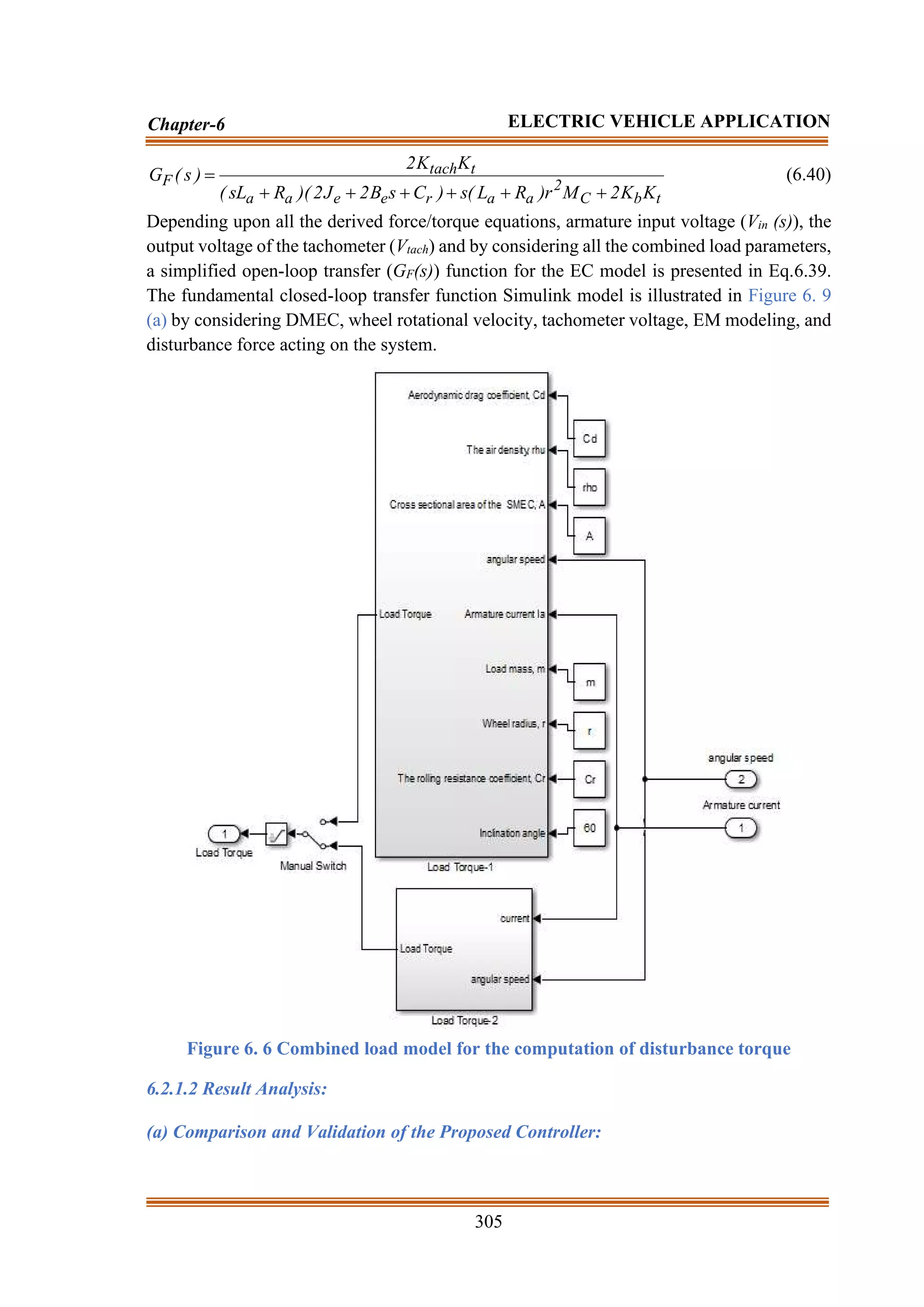

using the PWM technique, the controller sends the required ac power pulses to the EM as a

ratio of thousand times per second. The shorter pulses slow down the motor speed and longer

pulses increase the motor speed. Different control strategies are suggested for the specific

operation of the EC with specific merits and demerits. In this proposed approach, the most

important controllers such as PI, PID, and PI with a deadbeat controller and prefilter is

selected for specific control structure design action.

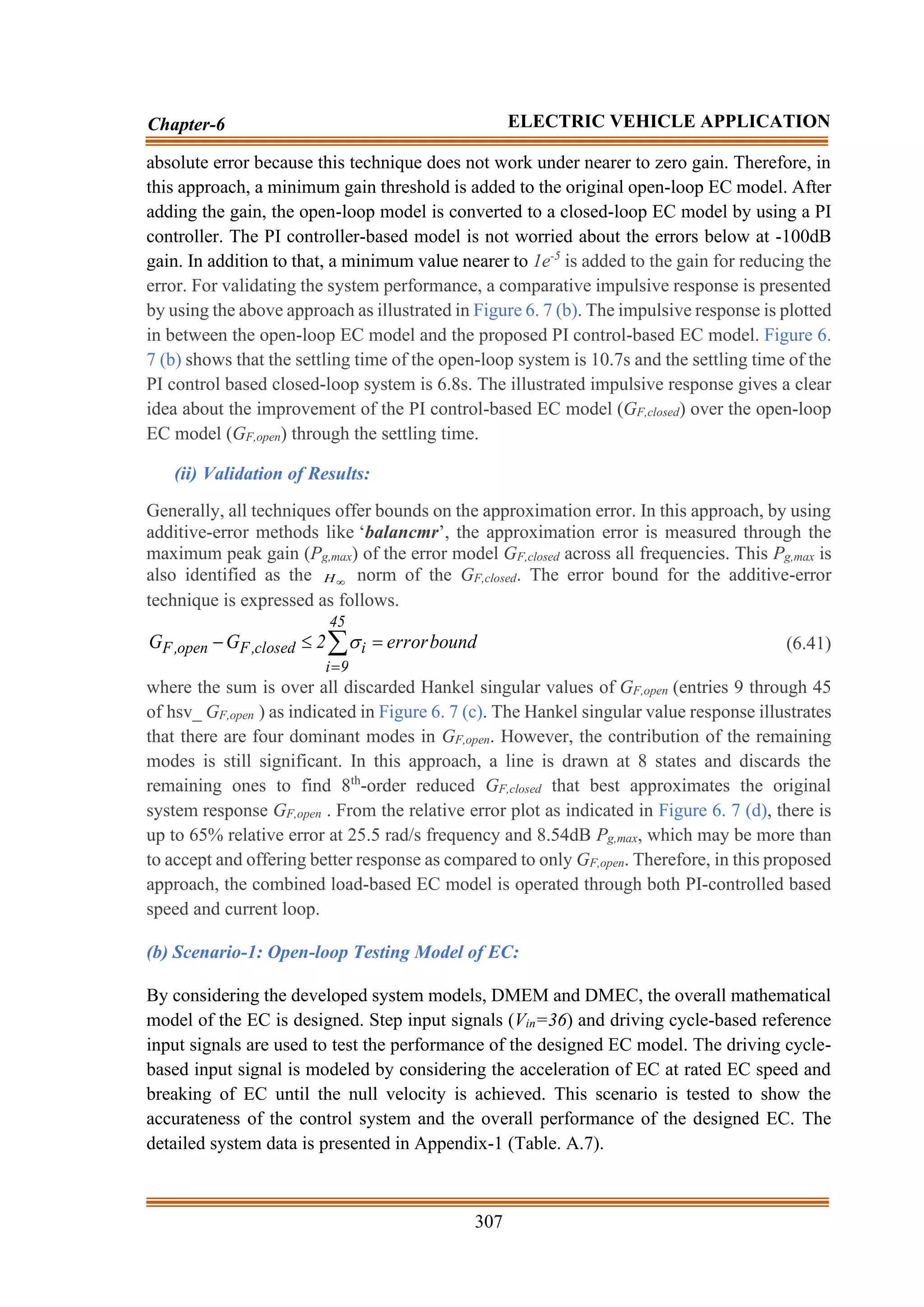

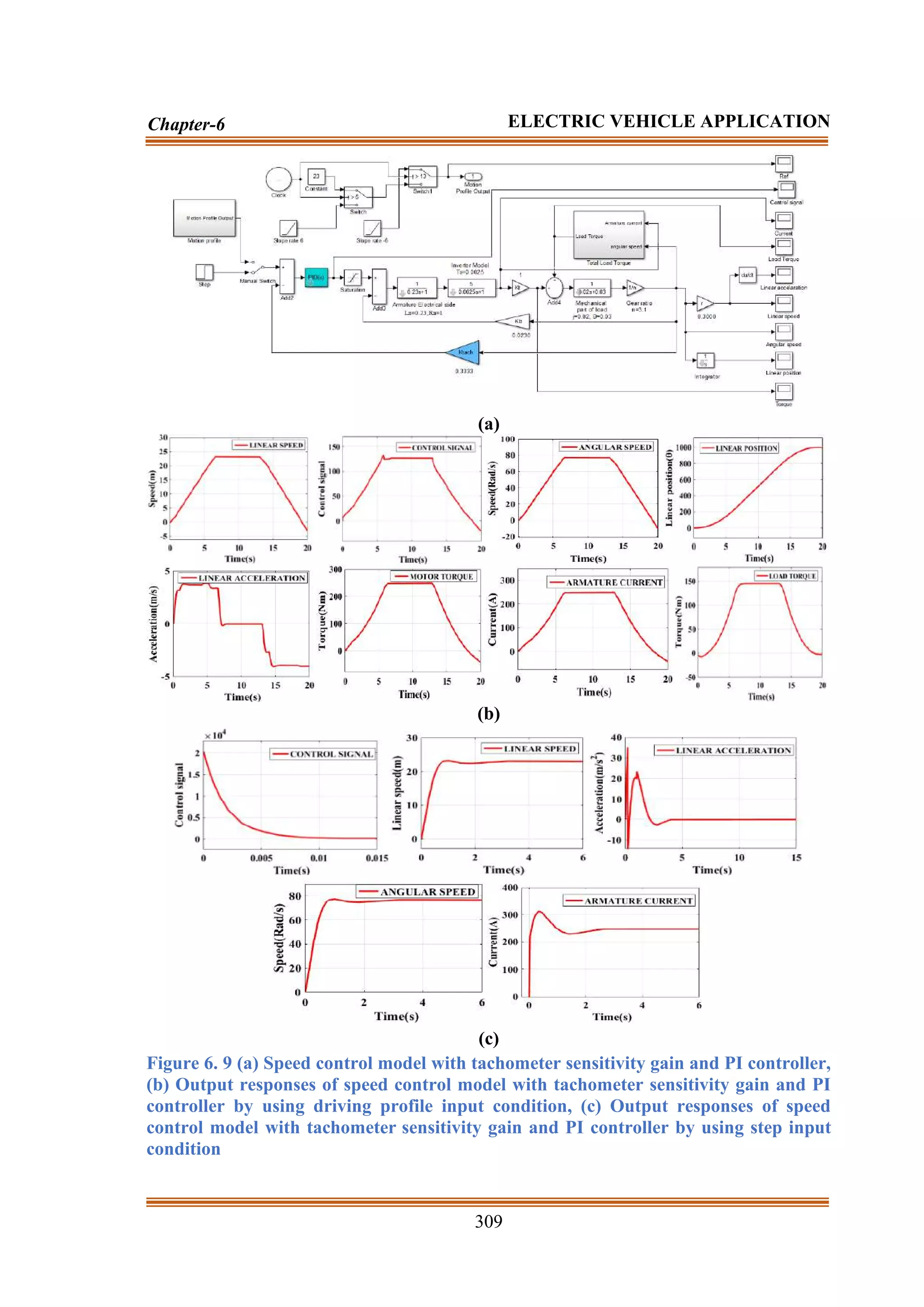

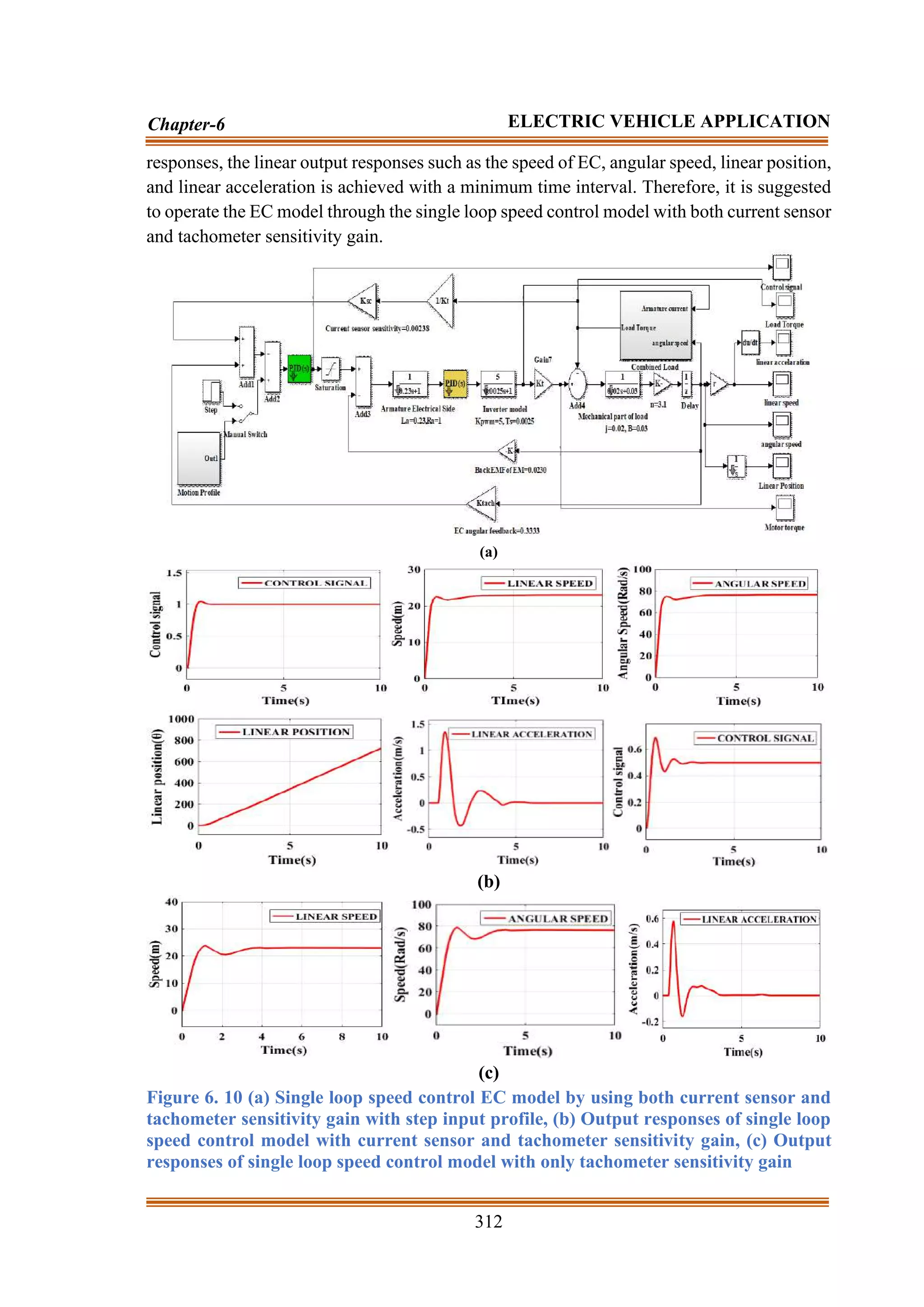

Control structure design for EC (model-1): In this proposed approach, a single PID

regulator-based closed-loop control approach is used to regulate the total EC system. The

total control approach for the EC as illustrated in Figure 6. 9 (a) is known as a speed regulator.

In this test condition, both of the load torque model illustrated in Figure 6. 9 is attached to

the system.

Testing: During the testing of the model, two reference input signals such as step input

(Vin=36) and driving profile input signals are considered. The reference input signals are

manually operated through a manual switch as illustrated in Figure 6. 9 (a). To test the EC

performance, firstly the driving profile is taken as input for the closed-loop EC model. In this

test condition, the most preferred Proportional Integral and Derivative Controller (PIDC) is

selected for controlling the errors generated during the transient condition. Different

strategies like optimization, self-tuning operations, and Zeigler Nicolas are commonly used

to compute the constant parameters. However, during the transient condition, the

computation performances are not well performed [15]. Therefore, in this proposed

approach, the selection of the PID controller parameter is achieved by using the simple

mathematical closed and open-loop time-domain analysis. The detailed explanations to the

constant parameter such as proportional (KP), integral (KI), and derivative (KD) are presented

in [15] by showing the stability criteria of the system. Similar to [15], in this approach, the

Kp, KI, and KD values are computed as 6.734528, 9.652537, and 1.248723 respectively.

In this condition by using the PID controller, the system responses are shown in Figure 6. 9

(b). Figure 6. 9 (b) shows the linear responses of current, speed, torque, and power by

considering the driving profile input. Figure 6. 9 (b) shows that the EC system achieves a

linear speed of 23m/s (approximately 82.8km/h) within 5s-6s time interval. Due to the use

of the PID controller, the linear control output of the PI controller is shown in Figure 6. 9

(b). According to the input condition profile, the angular speed of the motor is computed.

The angular speed of EM is computed around 80 rad/s. By using the computed angular speed,

the linear position of the motor speed is achieved at its desired value. The derivative of the

linear speed generates linear acceleration of the EC.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dr-211204045233/75/Robust-Active-Power-Filter-Controller-Design-for-Microgrid-and-Electric-Vehicle-Applications-part-2-107-2048.jpg)

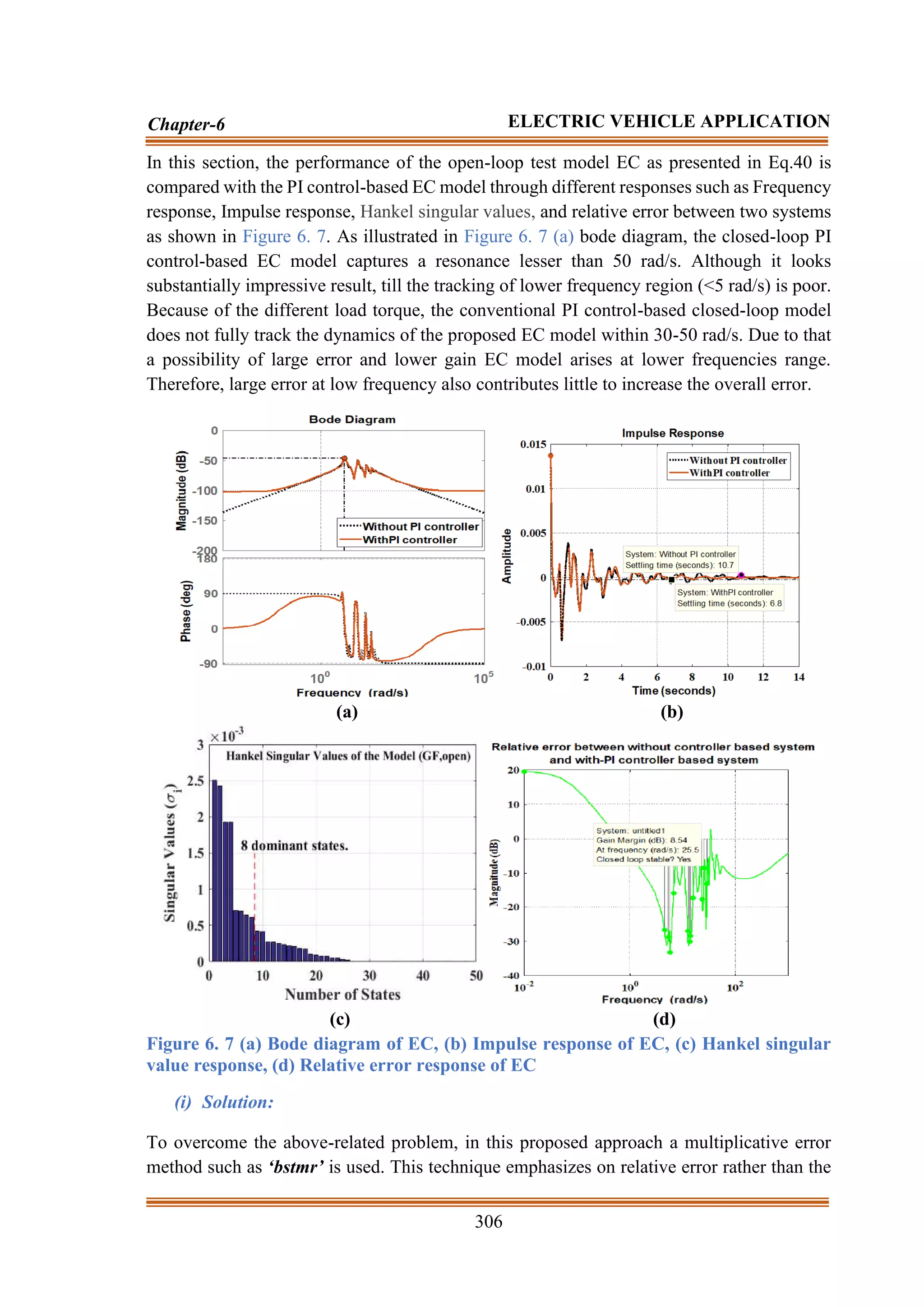

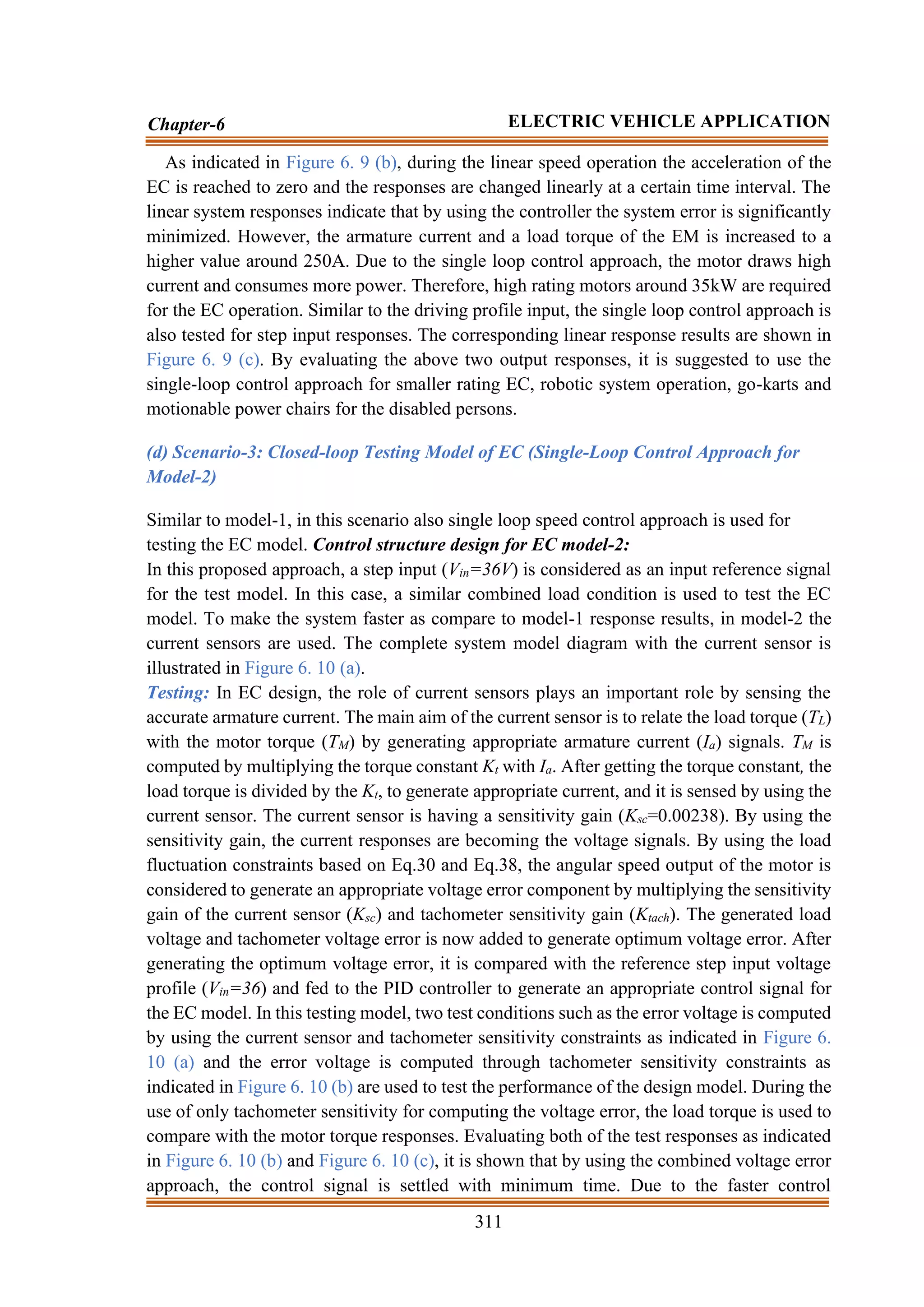

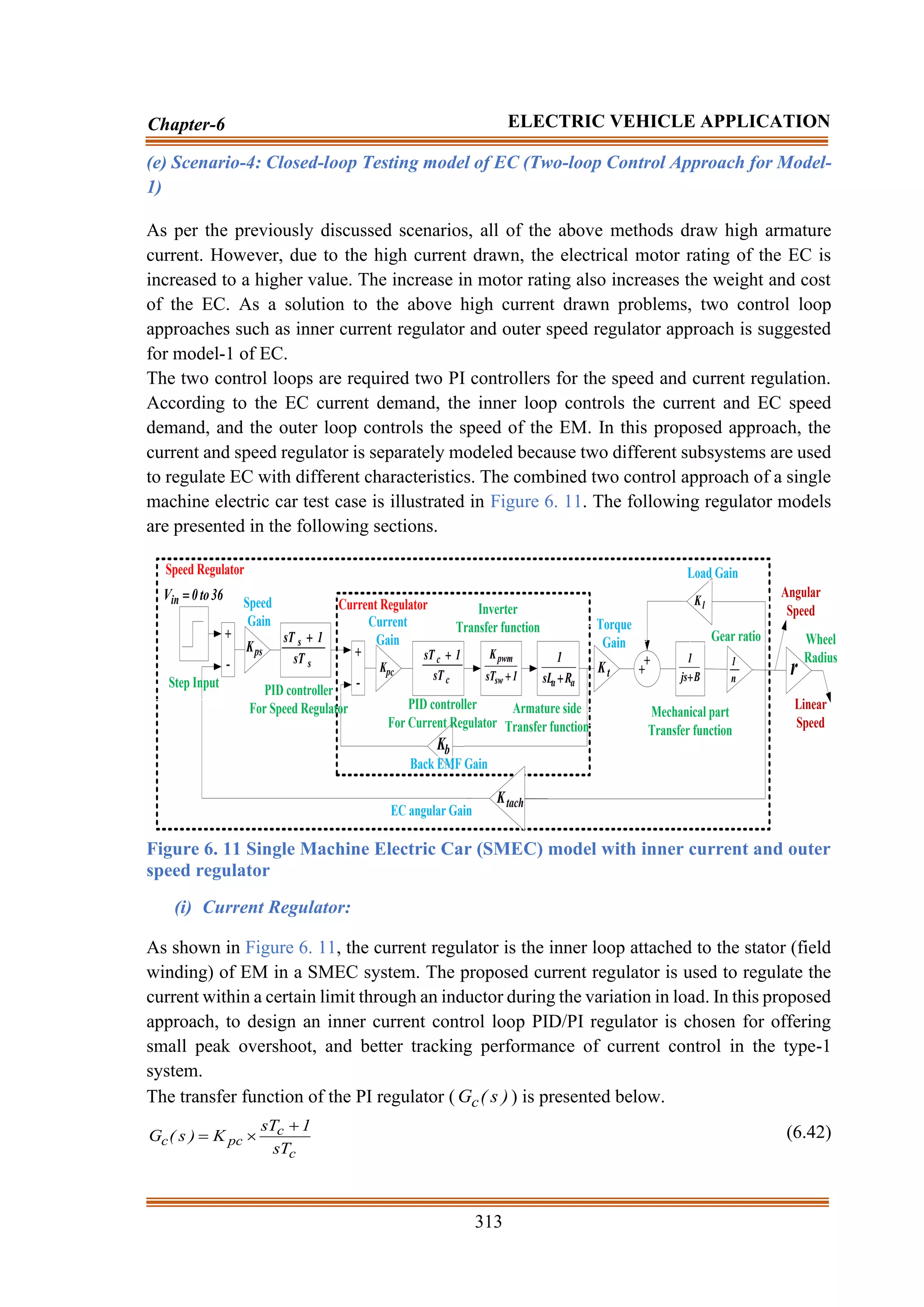

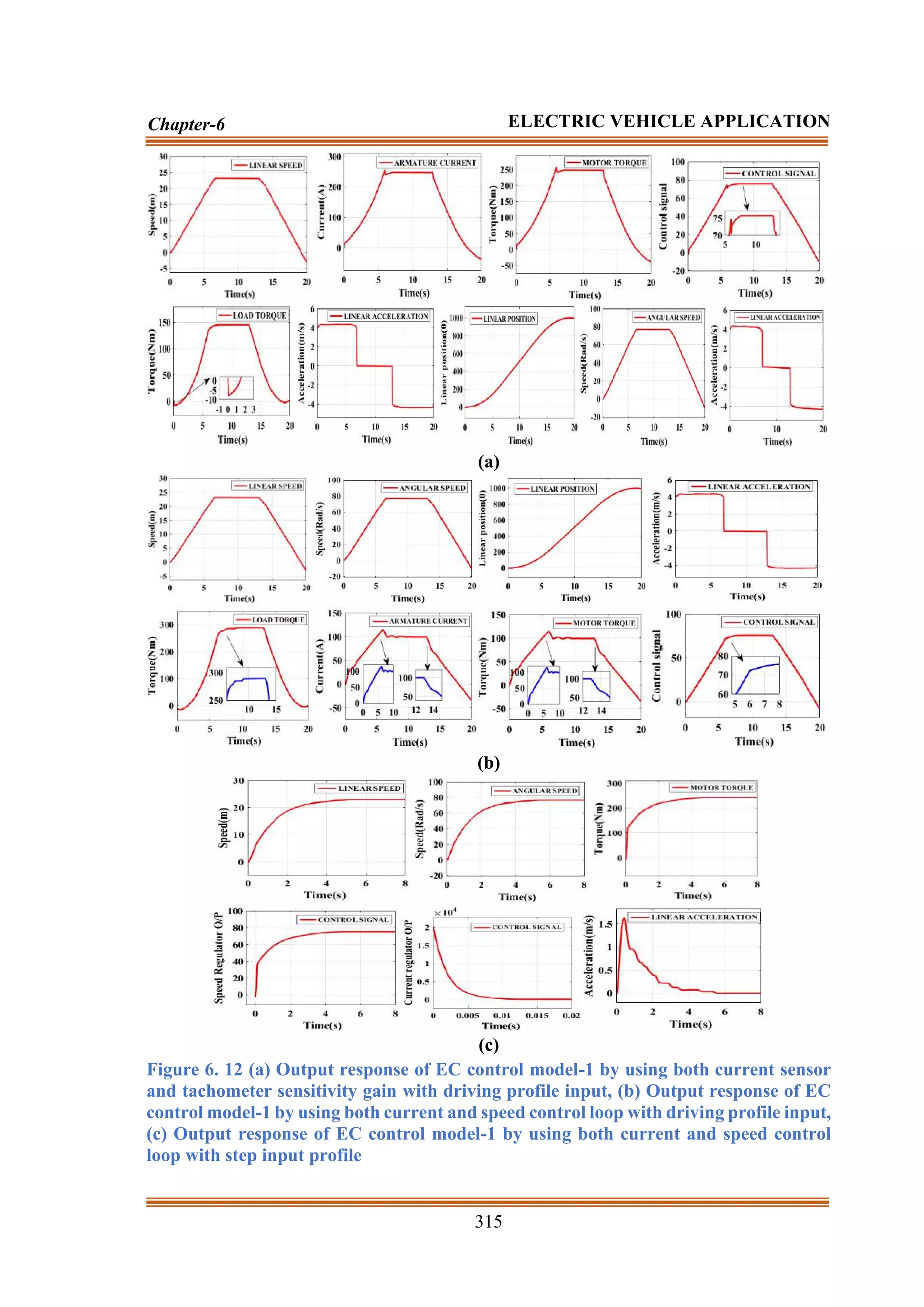

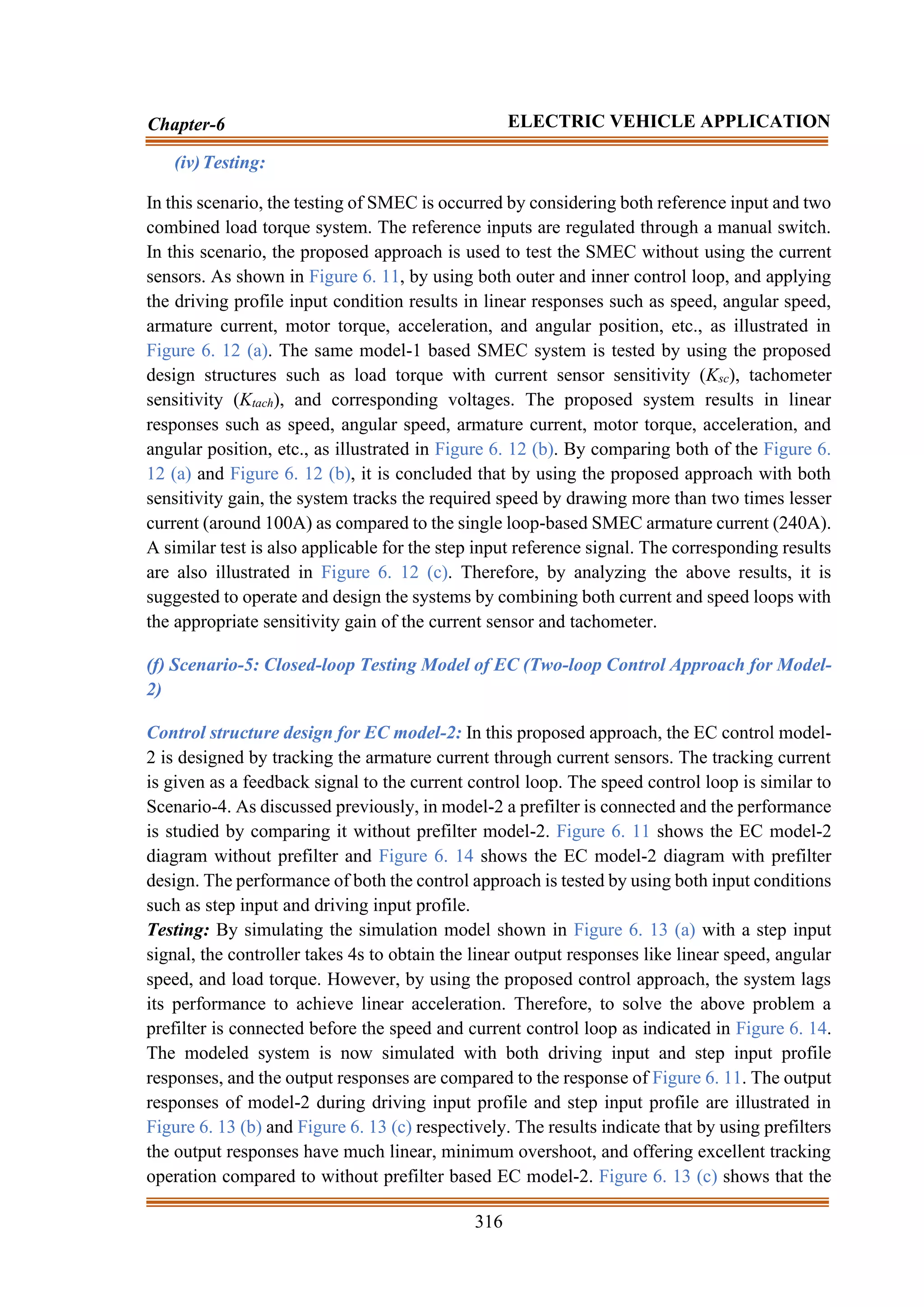

![314

Chapter-6 ELECTRIC VEHICLE APPLICATION

where Kpc is known as the proportional gain (nearer to 1.68), Kic is known as the integral

gain. Tc is denoted as the time constant of the PI regulator (near to 0.08 for faster action).

During the controller design, it is assumed that the proposed inner loop operates faster than

the outer loop. During the controller action, the PIzero (Z0=-Kic/Kpc) factor inversely affects

the system performance. Therefore, to eliminate the Z0 factor a prefilter is used in the SMEC

system. The transfer function of the prefilter ( )

s

(

Gp ) is presented as follows.

1

sT

1

z

s

z

)

s

(

G

c

0

0

p

+

=

+

= (6.43)

(ii) Speed Regulator:

As shown in Figure 6. 11, the speed regulator is the outer loop of the SMEC model. The

proposed speed regulator loop offers smooth and comfortable riding, zero steady-state error,

and reduces the disturbance during the transient conditions. In this proposed approach, for

achieving a comfortable condition a PID/PI control-based speed regulator is suggested. The

transfer function of the PI regulator for the speed regulator ( )

s

(

Gs ) is presented as follows.

+

=

+

=

+

=

+

=

s

ps

s

s

ps

ps

is

ps

is

ps

s

sT

1

1

K

sT

sT

1

K

s

K

K

s

K

s

K

sK

)

s

(

G (6.44)

where Kps is known as the proportional gain, and Kis is known as the integral gain. Ts is

denoted as the time constant of the PI regulator. The parameters of the PI regulator computed

from the open-loop transfer function is presented as follows.

D

is

D

ps

T

4

J

K

,

T

2

J

K =

= (6.45)

where TD is denoted as the combination of time delay due to the outer loop. In outer loop

condition also the prefilter approach is used to cancel the Z0 factor.

(iii) Inverter Model:

In this approach, the input voltage (Vin) is equal to 36, which is fed to the inverter. The role

of the inverter is to convert the dc voltage to ac voltage. The conversion is dependent upon

the pulse width modulation (PWM) strategy. The output voltage of the system is regulated

through the duty ratio (D) of the PWM signal. The transfer function of the inverter model (

)

s

(

Gi ) and related detailed explanation is presented in [324-326] as shown in Eq.6.46. The

inner loop PI regulator regulates the inverter switching frequency to decrease the ripples in

the motor torque and current in a SMEC system.

1

sT

K

)

s

(

G

sw

pwm

i

+

= (6.46)

where Kpwm is known as the inverter gain (nearer or equal to 5), and Tsw is the switching time

constant of the PWM controller (nearer to 0.25ms).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dr-211204045233/75/Robust-Active-Power-Filter-Controller-Design-for-Microgrid-and-Electric-Vehicle-Applications-part-2-111-2048.jpg)

![320

Chapter-6 ELECTRIC VEHICLE APPLICATION

Force

Resistance

External

FR =

Velocity

Car

VC =

Vehicle

the

of

Force

nal

Gravitatio

Fg =

Force

Inertial

FI =

Force

Traction

FT =

Force

Normal

FN =

Surface

Driving

the

of

Angle

=

MMRC

W

V

T

F

C

V

T

F

MMGW

M

RM

T

W

V

T

F

(a) (b) (c)

Force

c

Aerodynami

FA =

MMRC

1

T

F

C

V

MMGW

1

M

1

RM

T

1

W

V

MRMC

MMRC

MMGW

2

M

2

RM

T

2

W

V

C

V

2

T

F

2

T

F

1

T

F

1