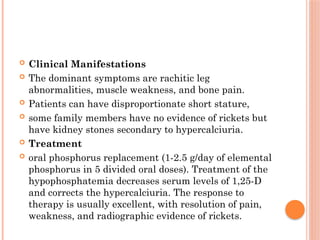

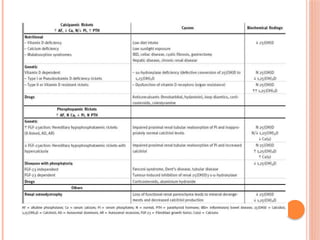

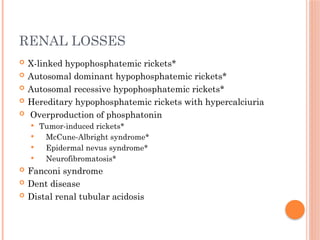

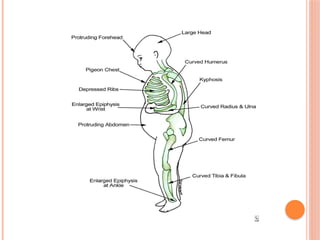

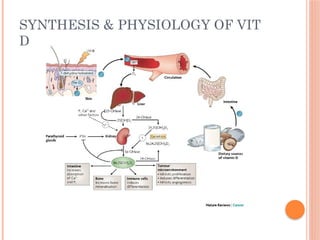

The document provides a comprehensive overview of rickets, detailing various causes such as vitamin D disorders, calcium and phosphorus deficiencies, and renal losses. It outlines clinical features, diagnosis, treatment options, prognosis, and prevention strategies, emphasizing the importance of adequate vitamin D, calcium, and phosphorus intake. Specific types of vitamin D-dependent rickets and their treatments are also discussed, along with genetic aspects and related complications.

![TREATMENT

providing adequate calcium, typically as a

dietary supplement

700 mg/day of elemental calcium [1-3 yr age],

1,000 mg/day of elemental calcium [4-8 yr age],

1,300 mg/day of elemental calcium [9-18 yr age]

Vitamin D supplementation is necessary if there

is concurrent vitamin D deficiency .

Prevention

discouraging early cessation of breast-feeding

and increasing dietary sources of calcium

school-based milk programs](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/rickets-250117131810-ed10d4b8/85/RICKETS-types-clinical-features-and-management-33-320.jpg)