This document discusses reading skills and the reading process. It covers several key points:

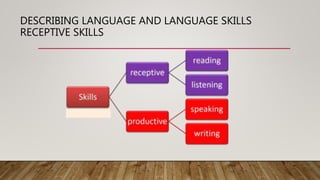

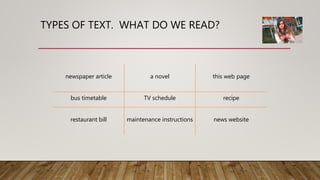

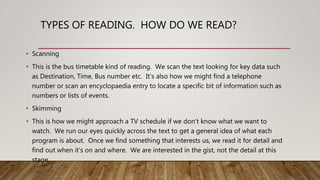

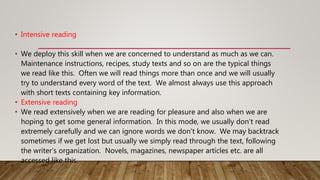

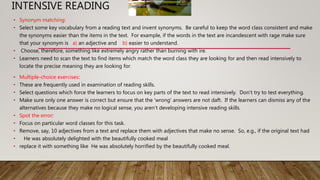

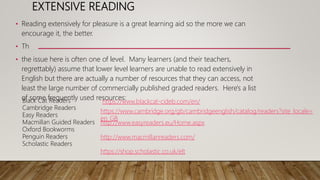

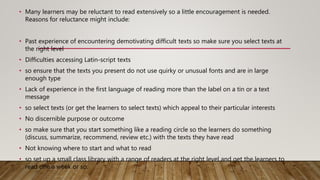

- There are different types of reading including scanning, skimming, intensive reading, and extensive reading that employ different strategies.

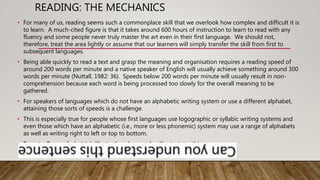

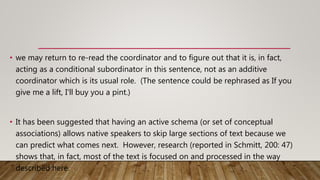

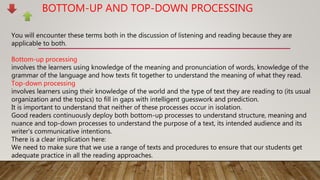

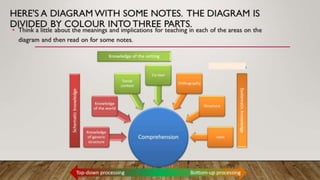

- The reading process involves both bottom-up processing of individual words and grammar as well as top-down processing using background knowledge.

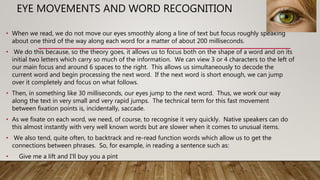

- Readers use eye movements to focus on words in short fixations and jumps to read text.

- Successful reading requires knowledge of text structure and genres, language elements, topics, and formal language skills like spelling and grammar.

- Readers deploy different skills depending on the text and their purpose in reading.