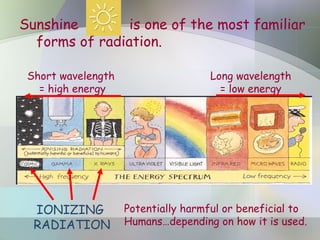

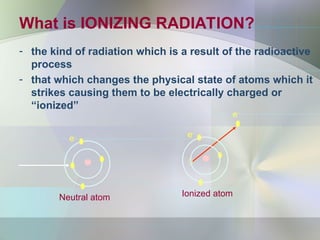

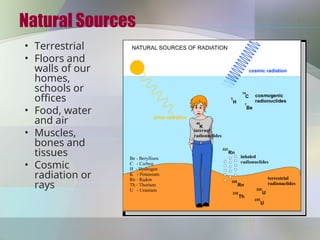

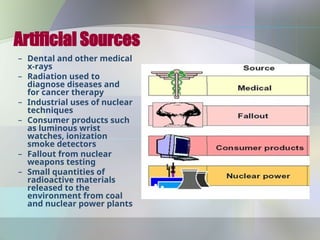

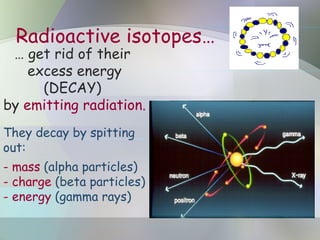

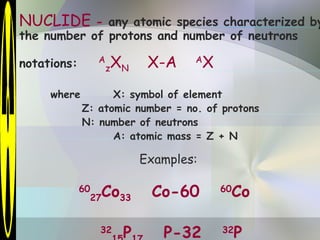

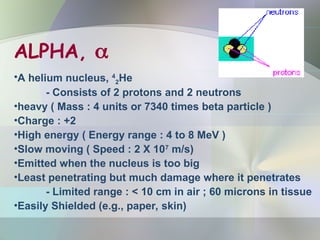

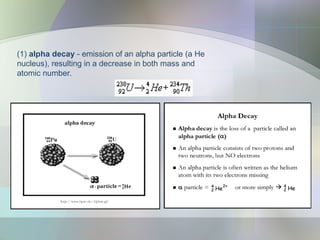

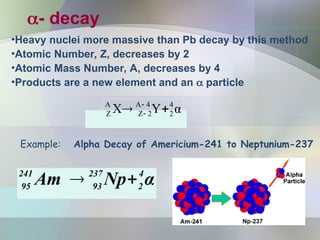

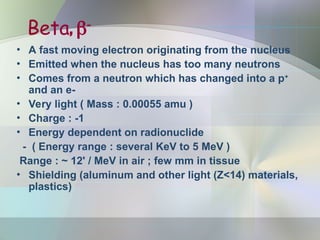

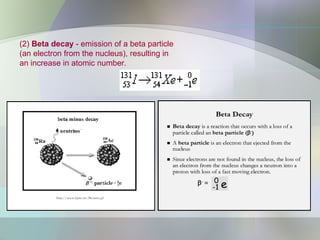

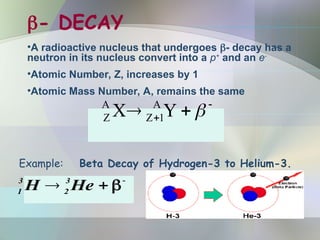

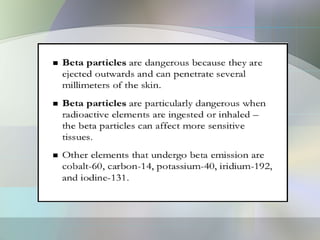

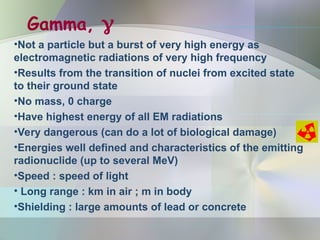

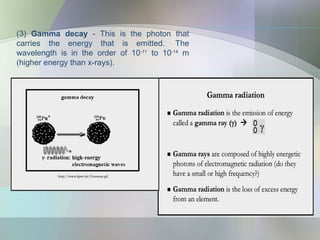

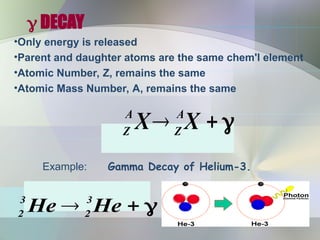

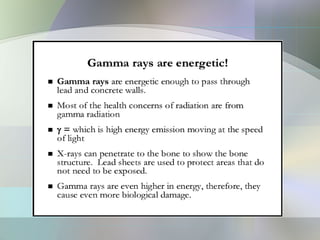

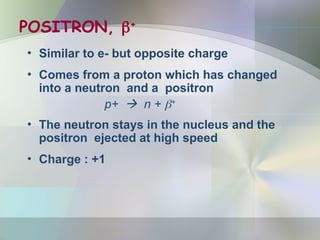

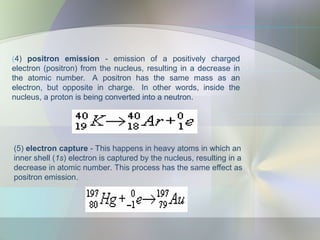

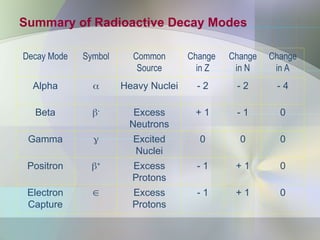

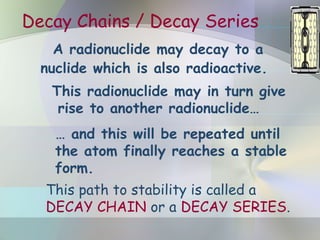

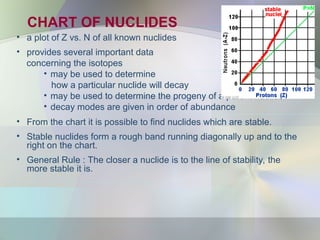

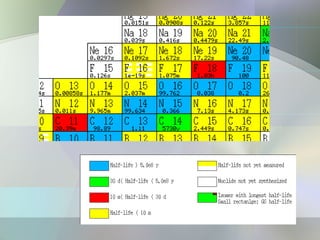

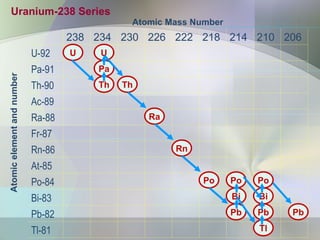

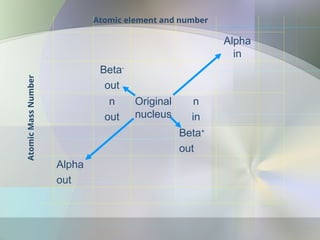

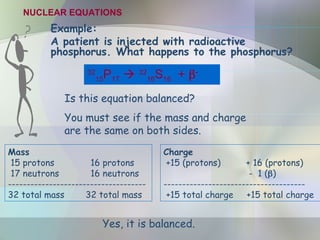

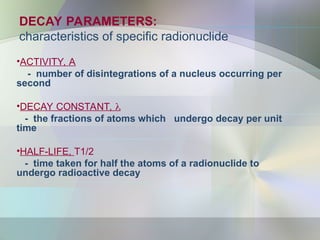

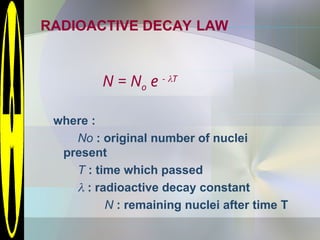

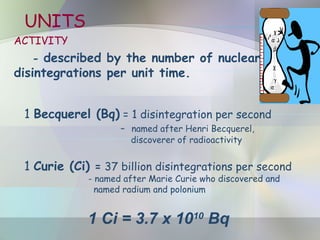

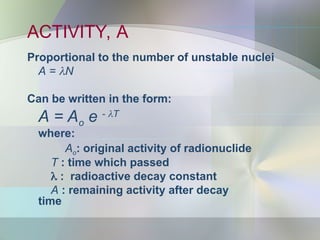

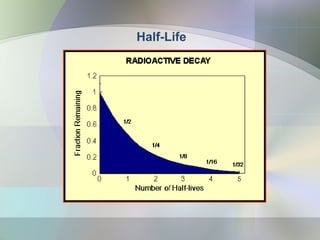

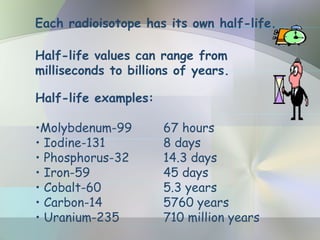

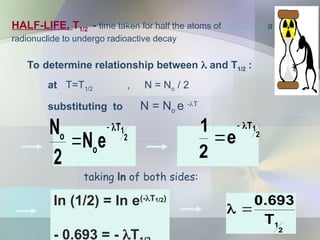

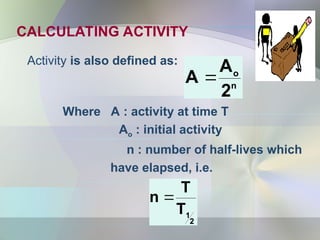

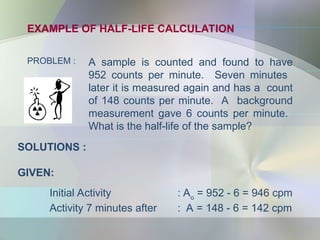

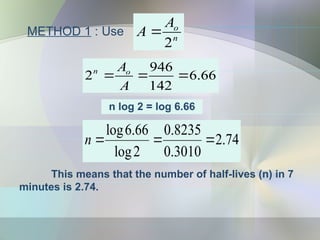

The document provides an overview of radioactivity, describing various types of radiation, their sources, and the process of radioactive decay. It explains the differences between ionizing and non-ionizing radiation, as well as the types of decay (alpha, beta, gamma) and related concepts such as half-life and decay chains. Additionally, it discusses the practical applications of radiation in medicine, industry, and research, highlighting the importance and prevalence of radiation in everyday life.