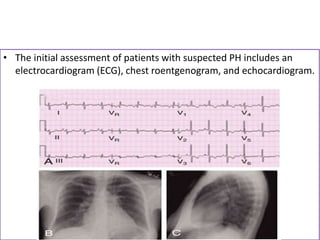

The document outlines the diagnosis and management of pulmonary hypertension (PH), detailing its definition, initial assessments, and various diagnostic tools. It emphasizes the importance of an integrated diagnostic approach, including imaging, functional tests, and cardiac catheterization, alongside treatment options depending on the etiology of PH. Additionally, it discusses recent studies evaluating therapies such as bosentan and riociguat, highlighting their safety and efficacy in treating pulmonary arterial hypertension and chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension.

![5 Computed tomographic chest imaging and nuclear

ventilation/perfusion (V/Q) scintigraphy- Mismatched perfusion

defects on ventilation-perfusion (V/Q) scintigraphy is highly suggestive

of CTEPH.

• The CT signs suggesting the presence of PH include an enlarged PA

diameter, a PA-to-aorta ratio >0.9, and enlarged right heart

chambers.

• A combination of three parameters (PA diameter ≥30 mm, RVOT wall

thickness ≥6 mm, and septal deviation ≥140° [or RV:LV ratio ≥1]) is

highly predictive of PH.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pulmonaryhypertension-240131132156-8513b691/85/Pulmonary-Hypertension-pptx-15-320.jpg)

![• Pulmonary vascular resistance ([mPAP−PAWP]/CO) should be

calculated for each patient.

• All pressure measurements, including PAWP, should be performed at

end expiration (without breath-holding manoeuvre).

• In patients with large intrathoracic pressure changes during the

respiratory cycle (i.e. COPD, obesity, during exercise), it is appropriate

to average over at least three to four respiratory cycles.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pulmonaryhypertension-240131132156-8513b691/85/Pulmonary-Hypertension-pptx-21-320.jpg)