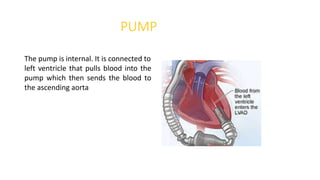

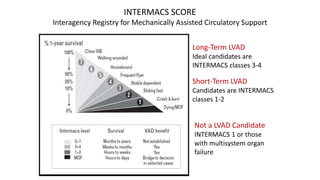

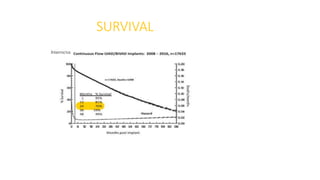

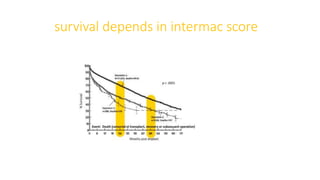

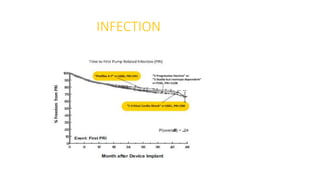

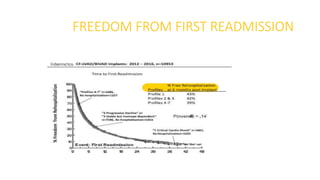

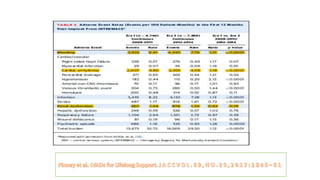

Left ventricular assist devices (LVADs) can provide long-term support for patients with end-stage heart failure who are not candidates for transplant. Continuous-flow LVADs have high 1- and 2-year survival rates of 80% and 70% respectively. While LVADs improve survival and quality of life, patients face risks of complications like bleeding, infection, stroke, and device malfunction. Ongoing management requires careful monitoring and optimization of patient hemodynamics and medical therapies.