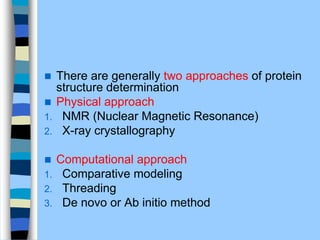

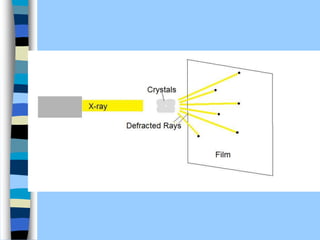

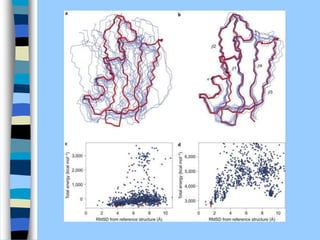

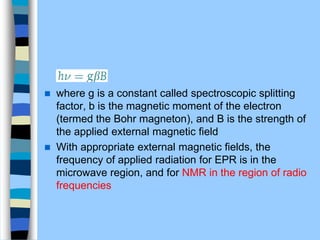

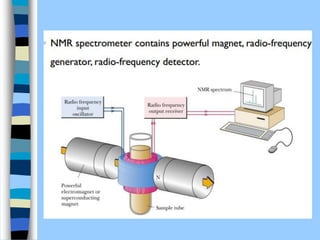

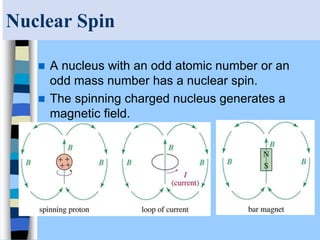

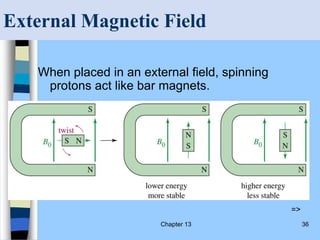

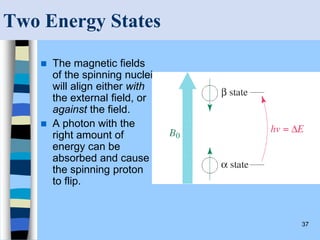

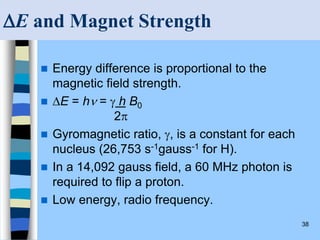

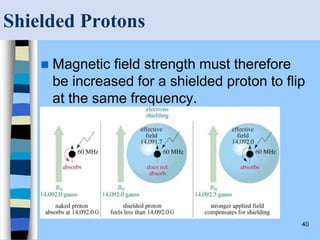

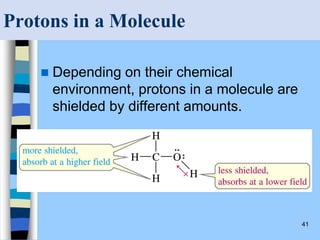

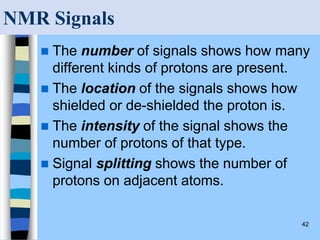

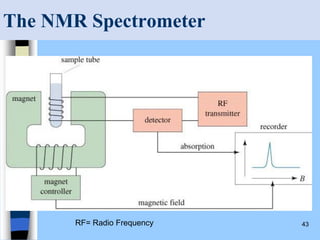

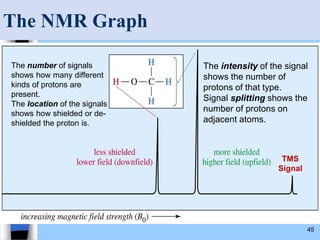

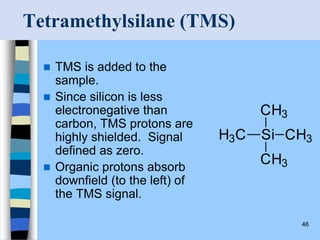

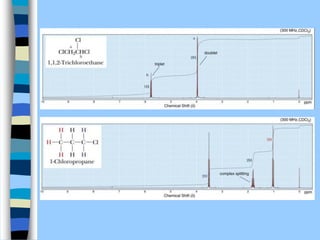

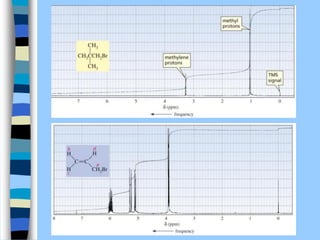

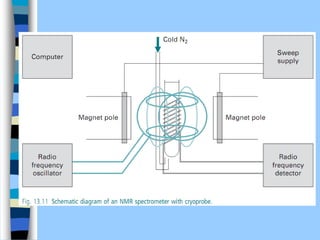

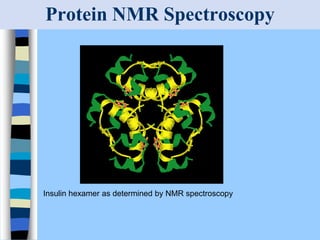

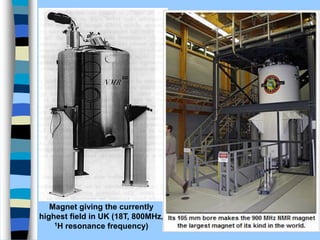

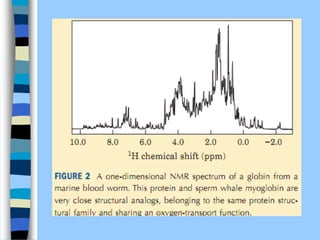

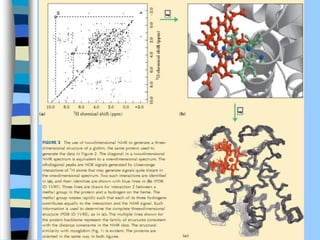

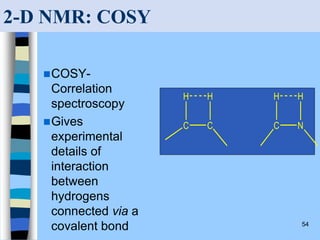

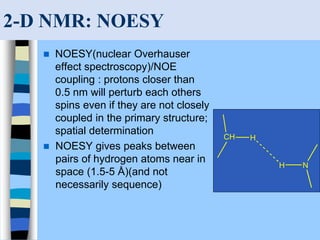

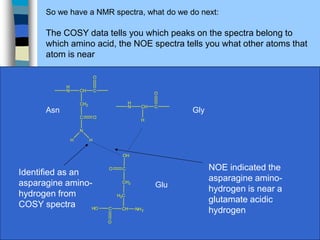

There are two main approaches to determining protein structure - physical methods like NMR and X-ray crystallography, and computational methods like comparative modeling. NMR spectroscopy is a powerful tool that can be used to determine protein structures in solution. It works by applying a strong magnetic field to align nuclear spins, then applying radio waves to induce transitions between spin states. This provides information about interatomic distances that can be used to build 3D protein structures. COSY data identifies which peaks correspond to which amino acids, while NOESY data provides spatial information about nearby atoms. Together this data is used to determine protein conformations and dynamics in vivo.