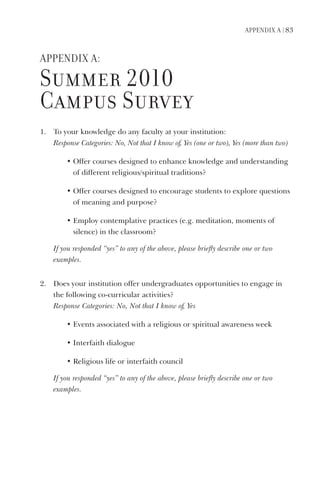

This document provides an overview of a guidebook called "Promising Practices: Facilitating College Students' Spiritual Development". The guidebook was created based on findings from the Spirituality in Higher Education national study to provide examples of programs and practices that support students' spiritual growth in college. The guidebook includes descriptions of curricular initiatives, co-curricular programs, and campus-wide efforts related to spirituality from over 400 institutions. The goal is to help more colleges and universities undertake initiatives to foster students' spiritual development.