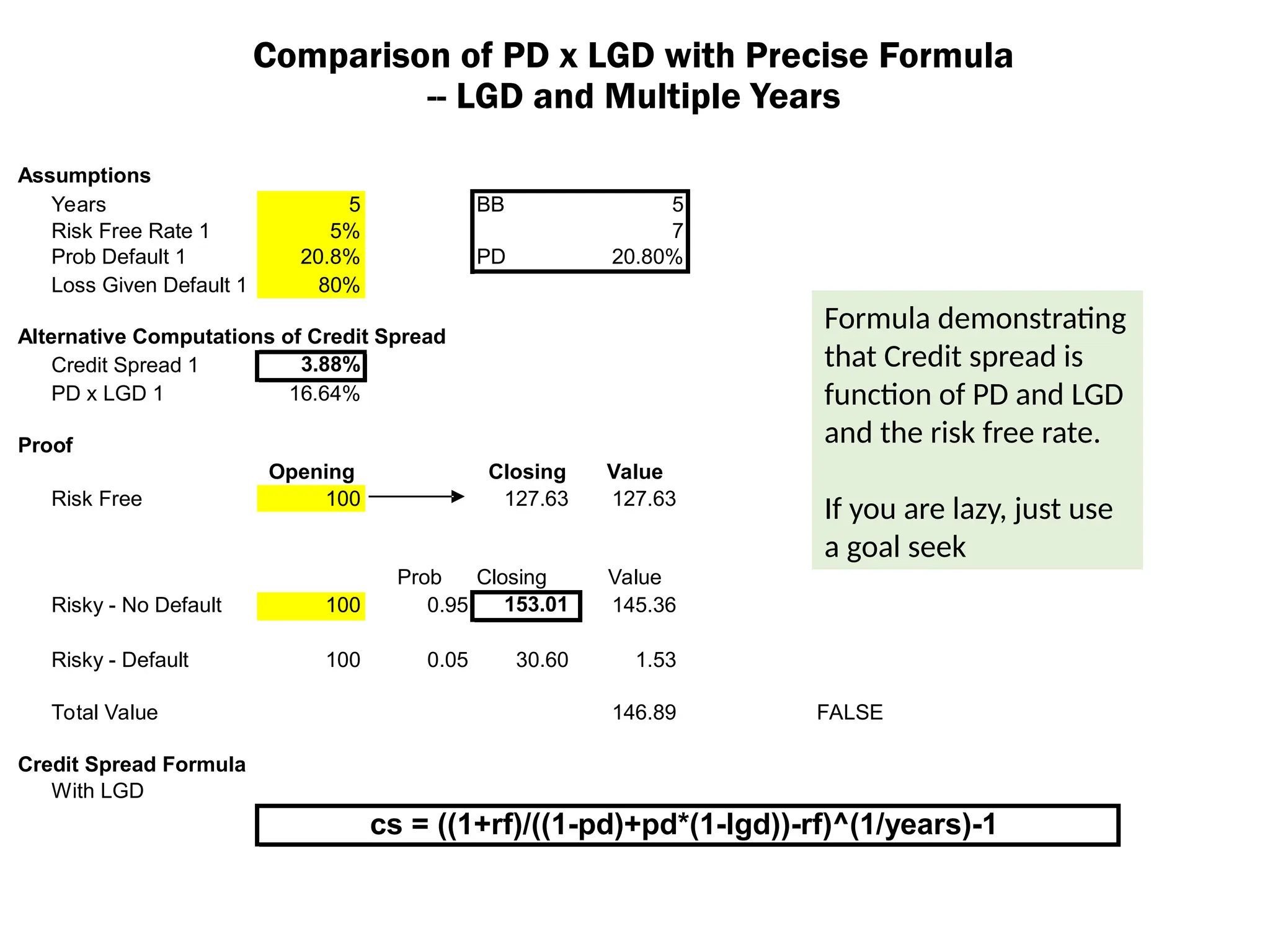

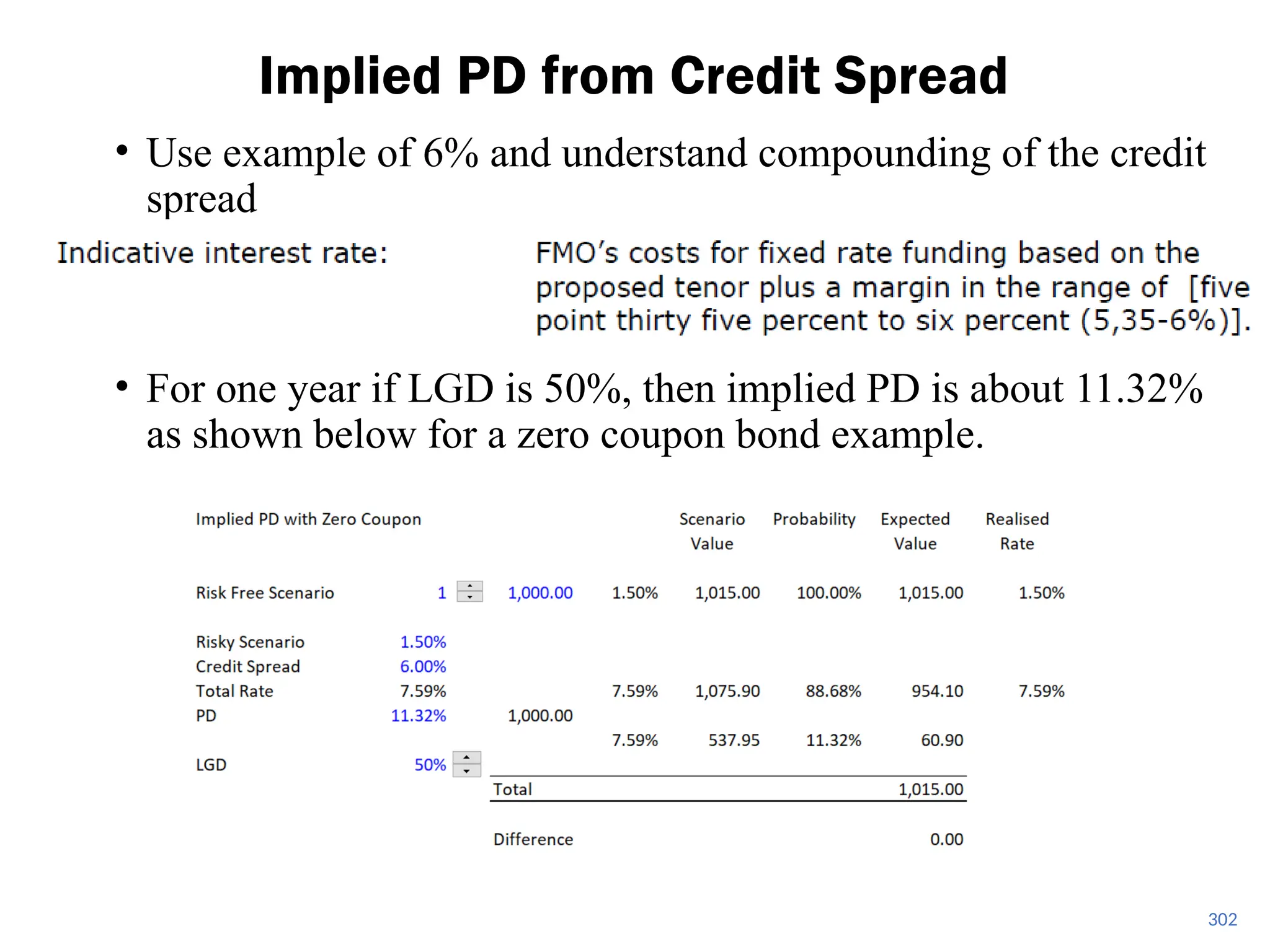

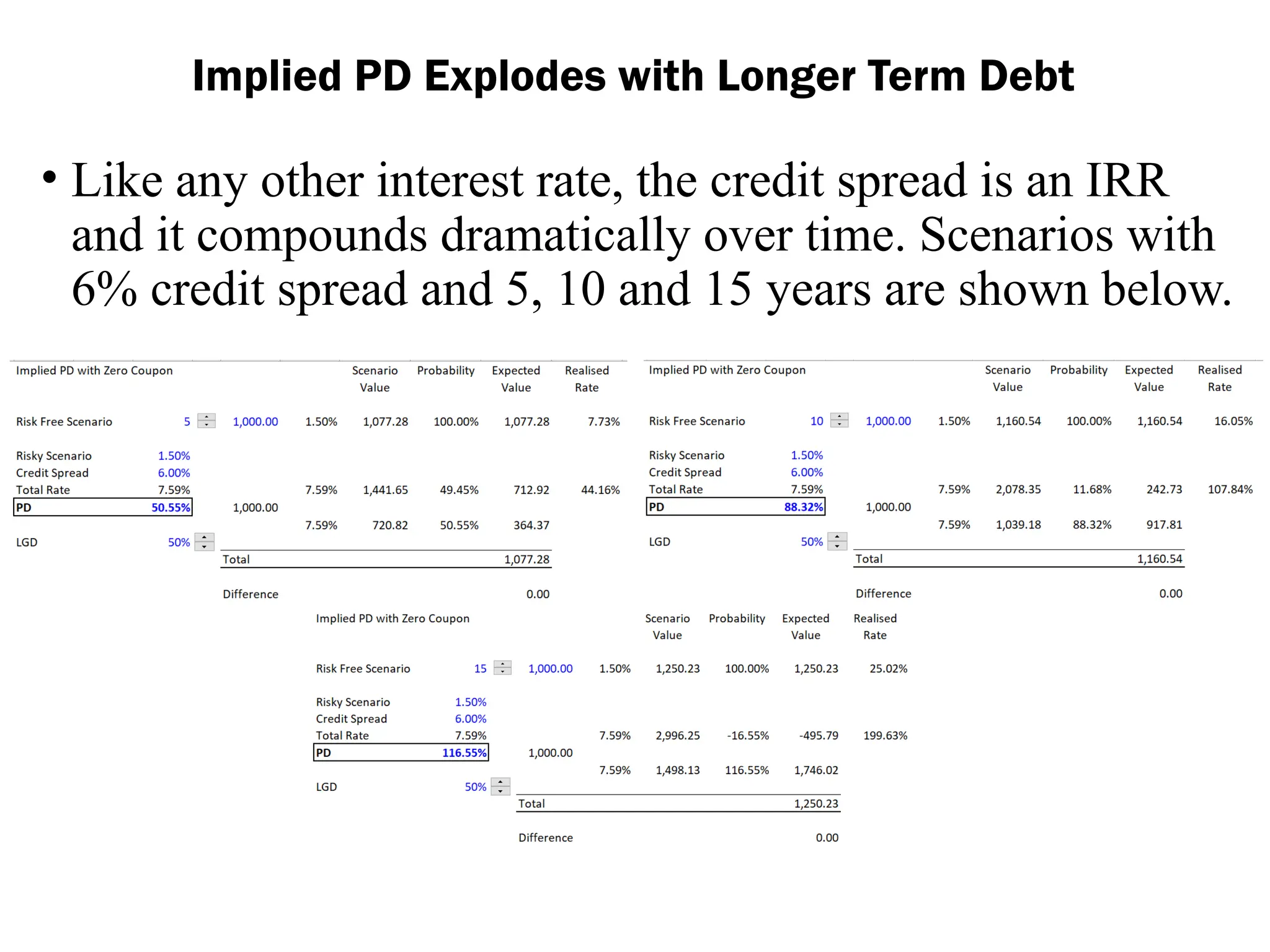

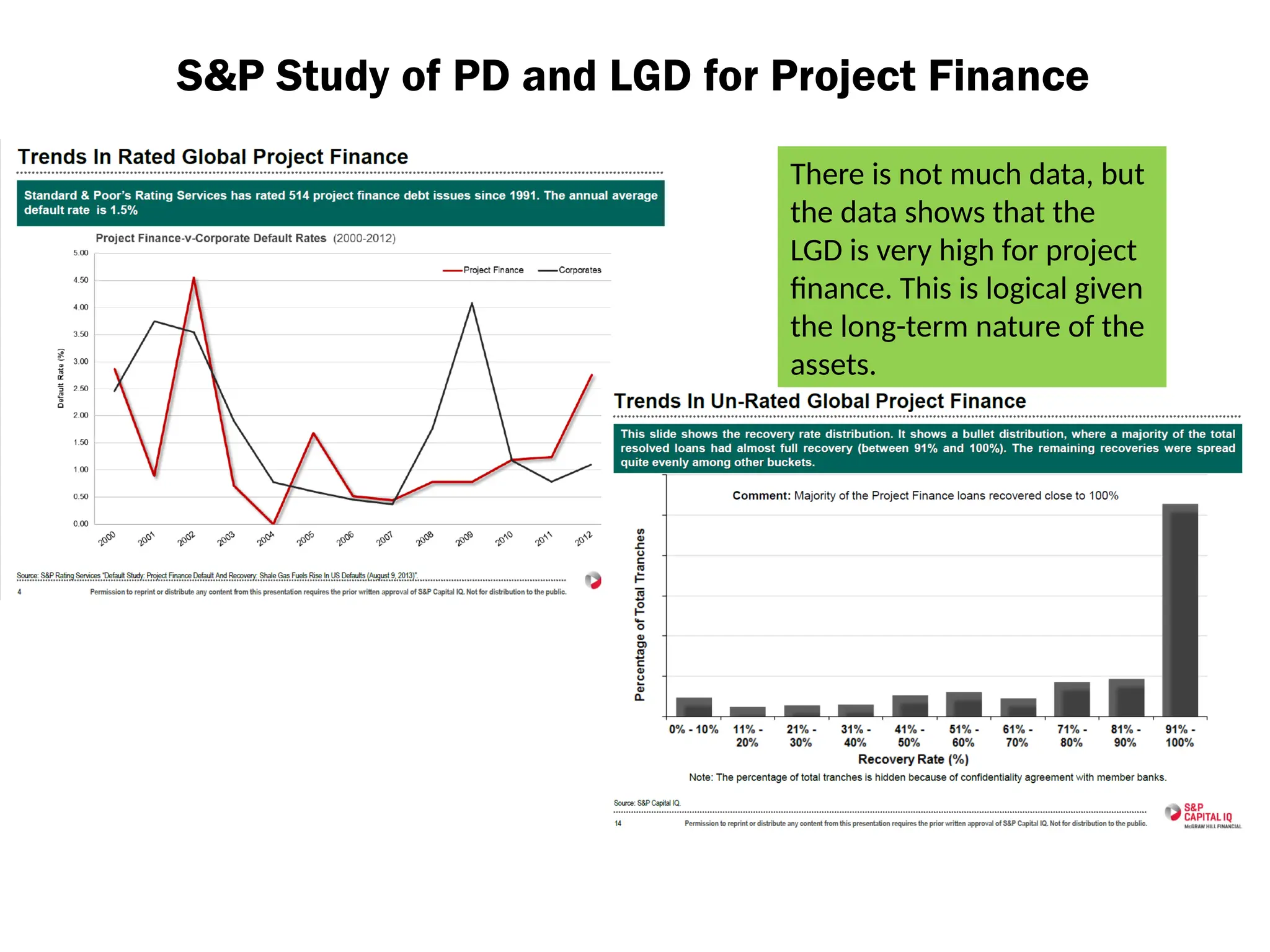

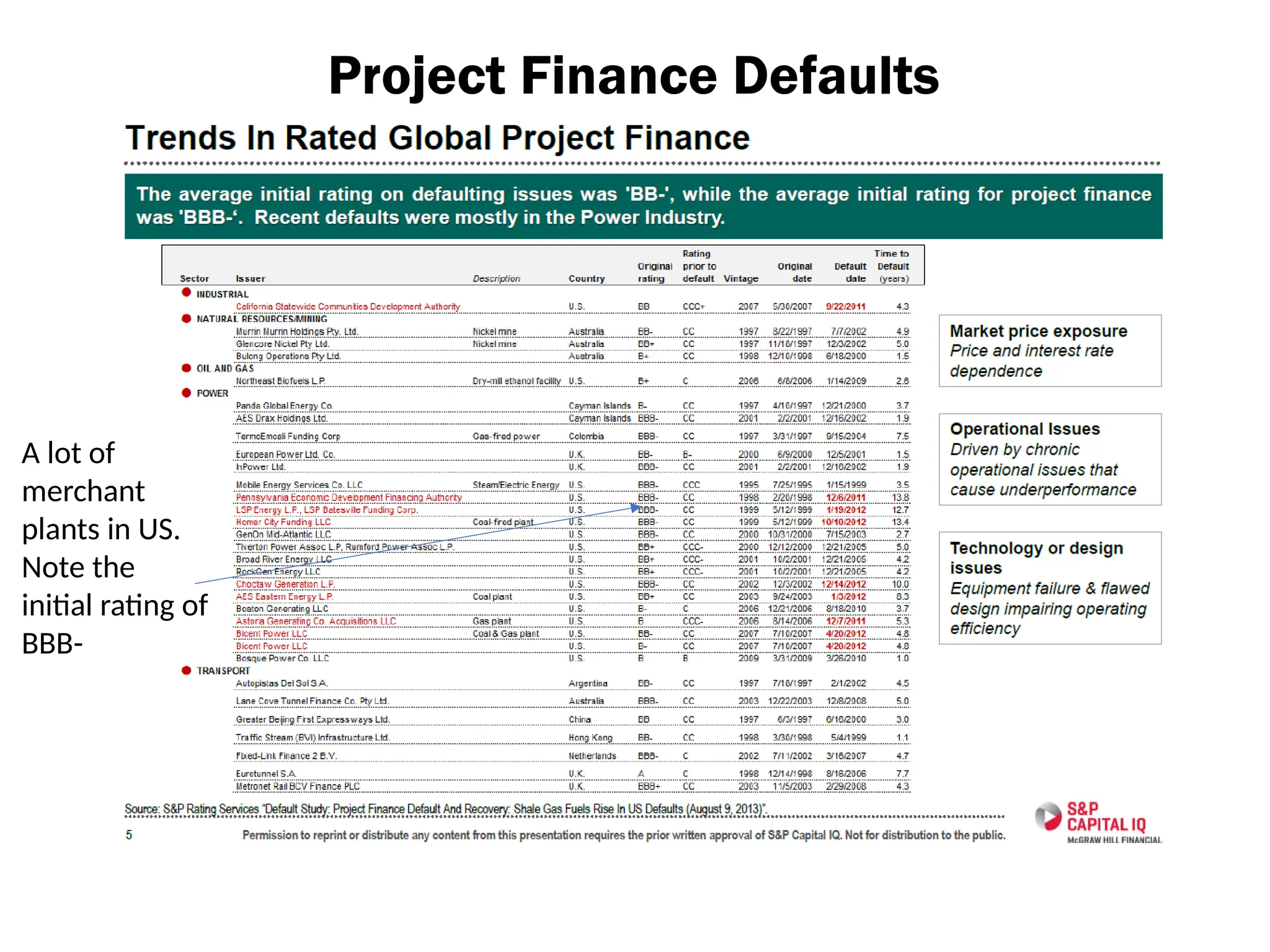

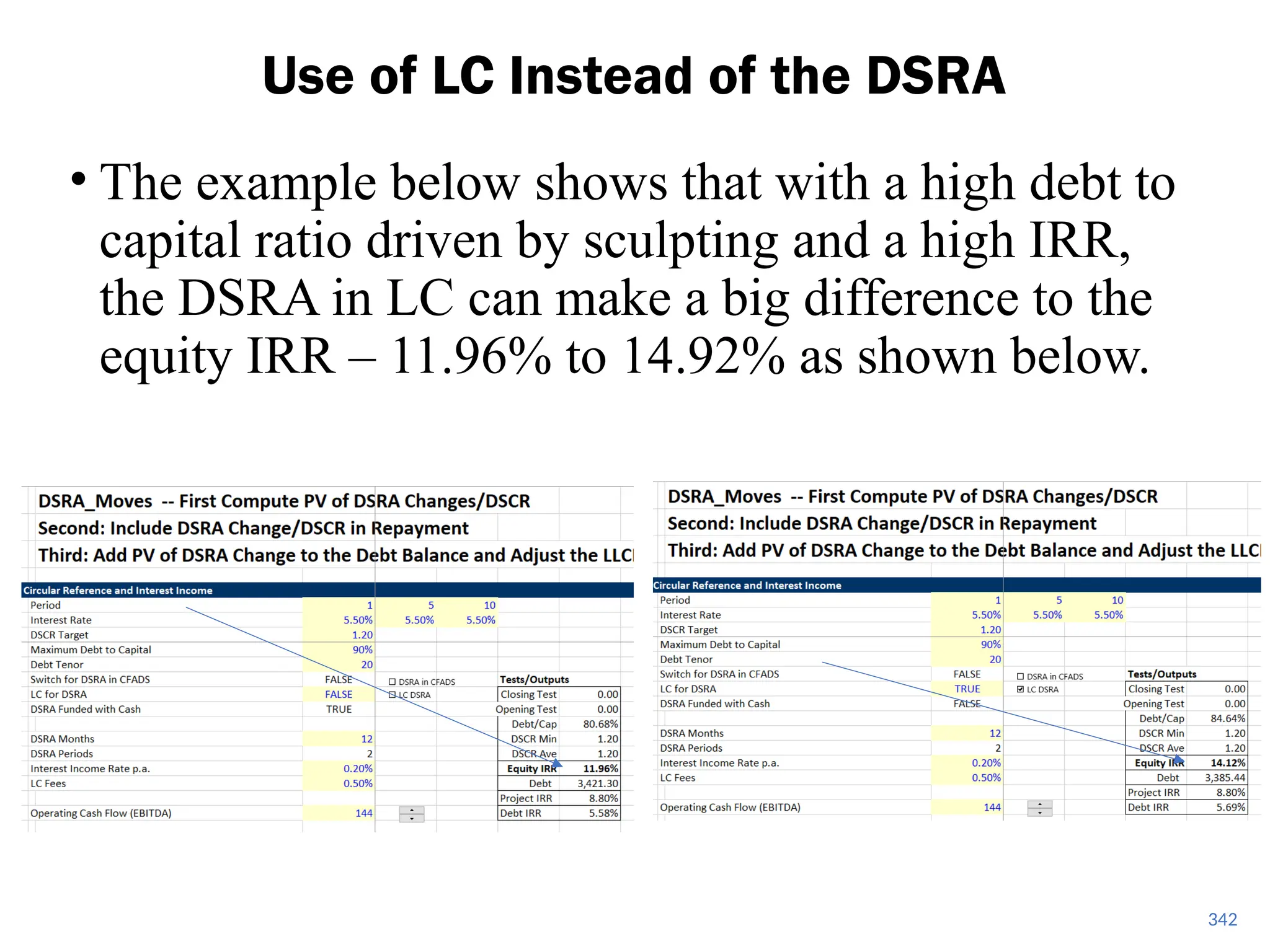

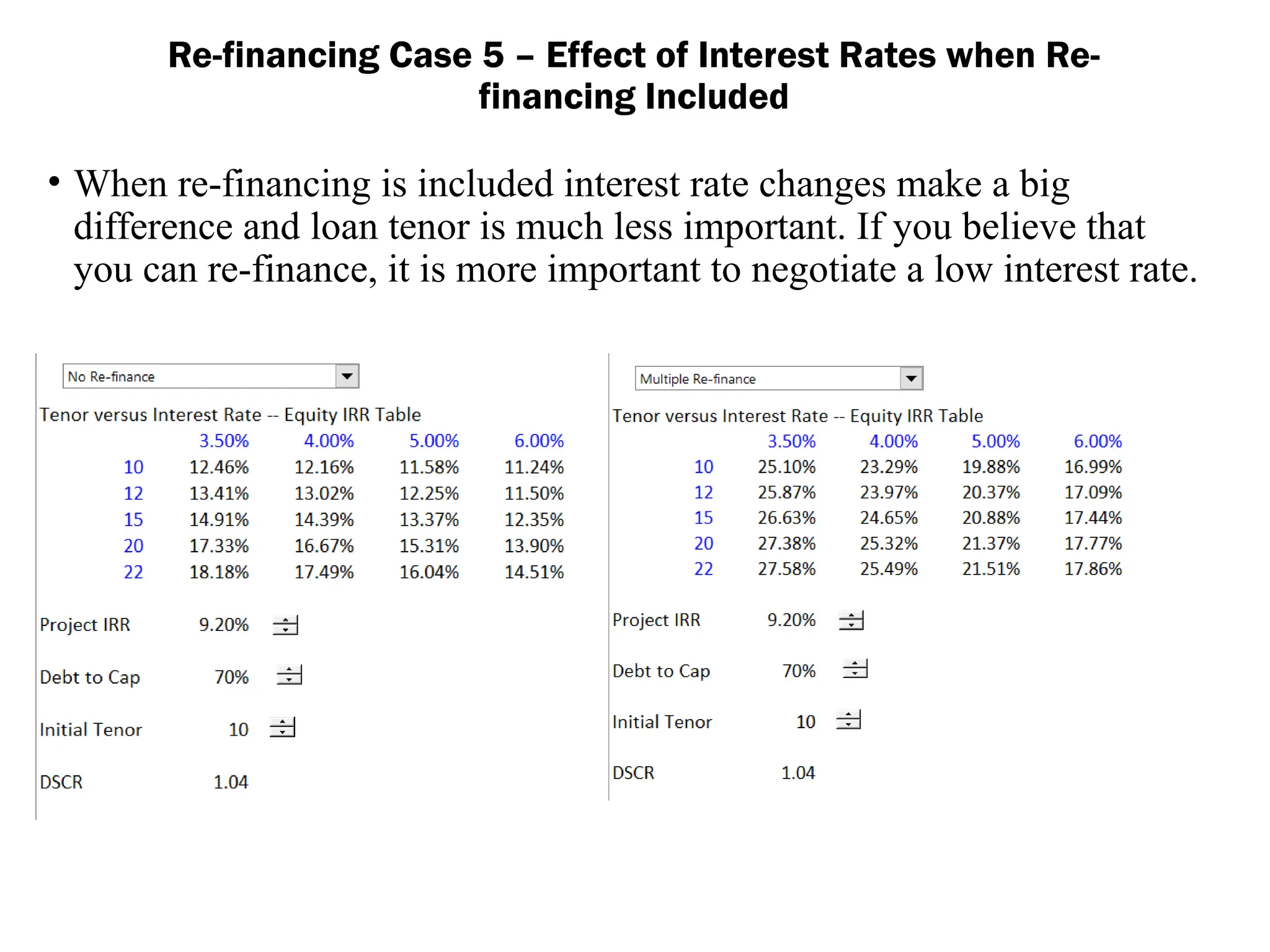

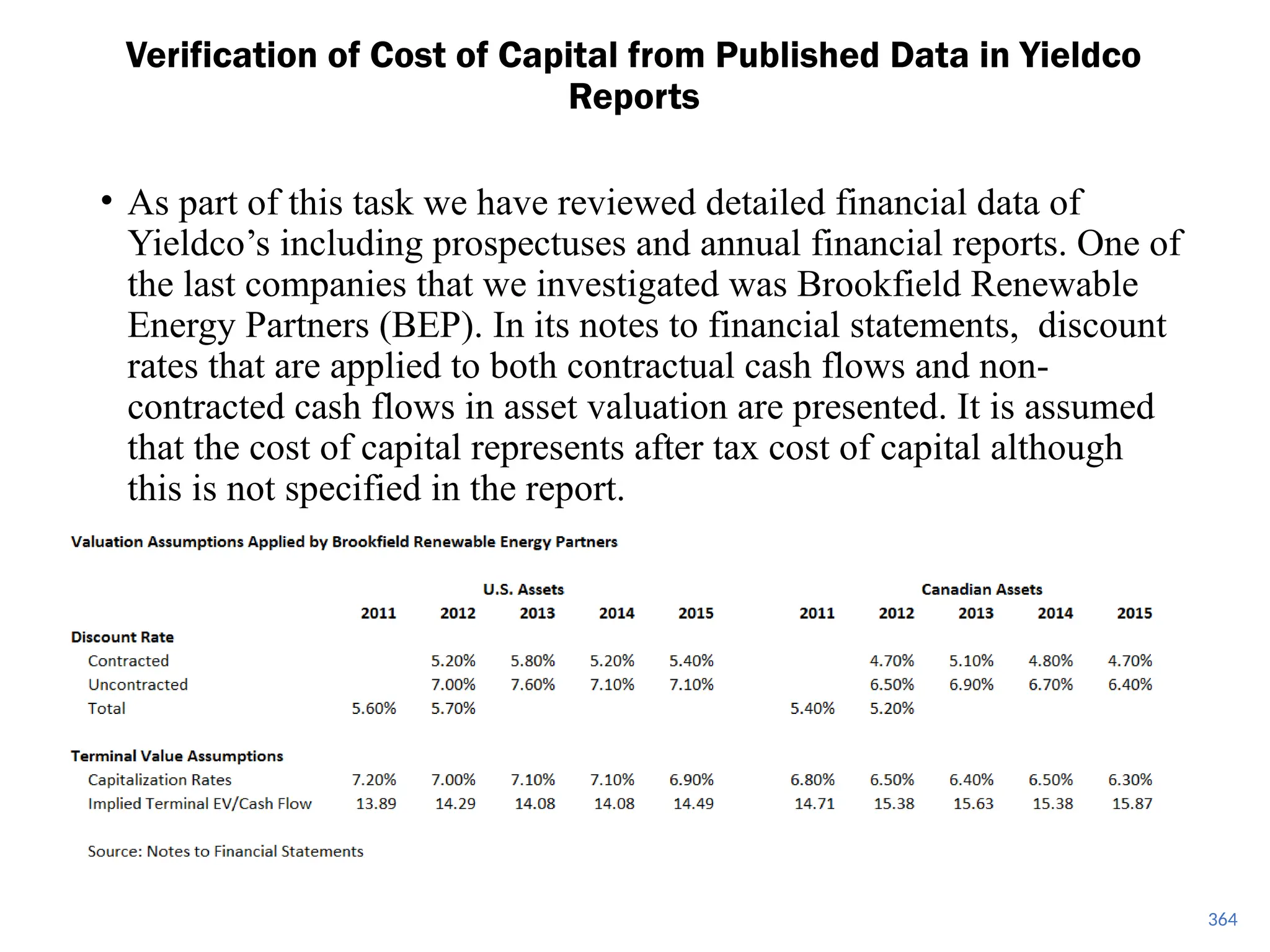

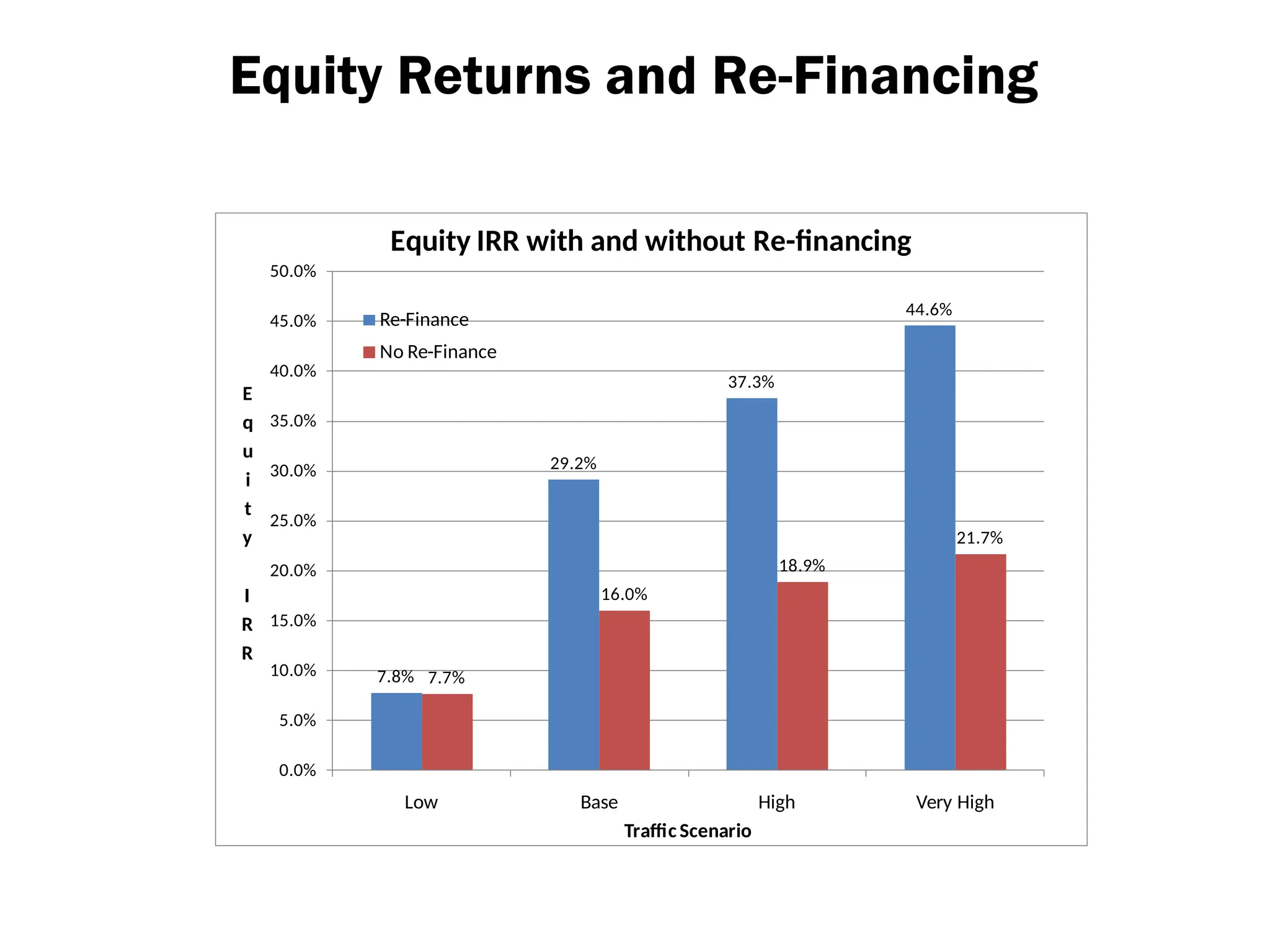

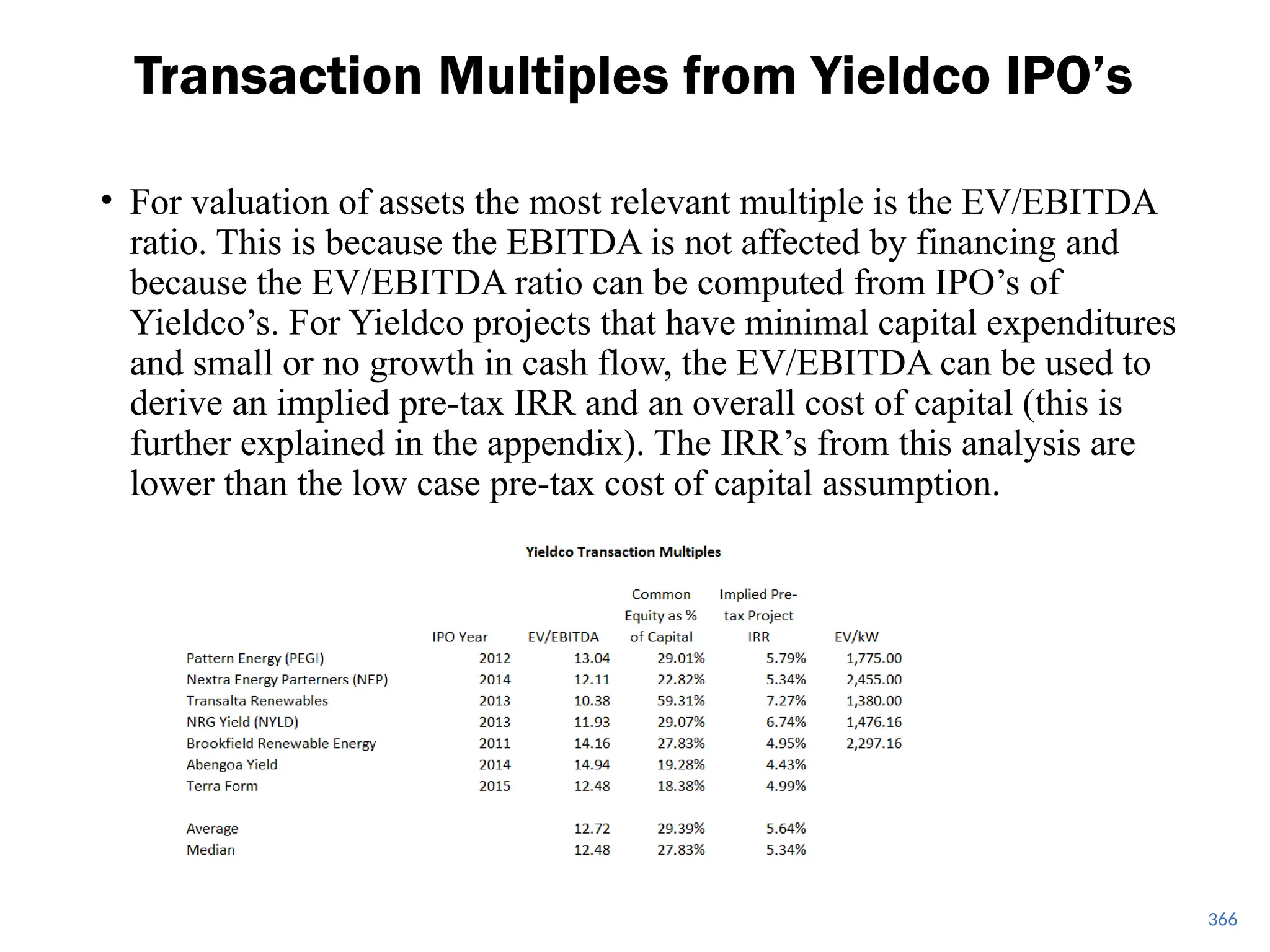

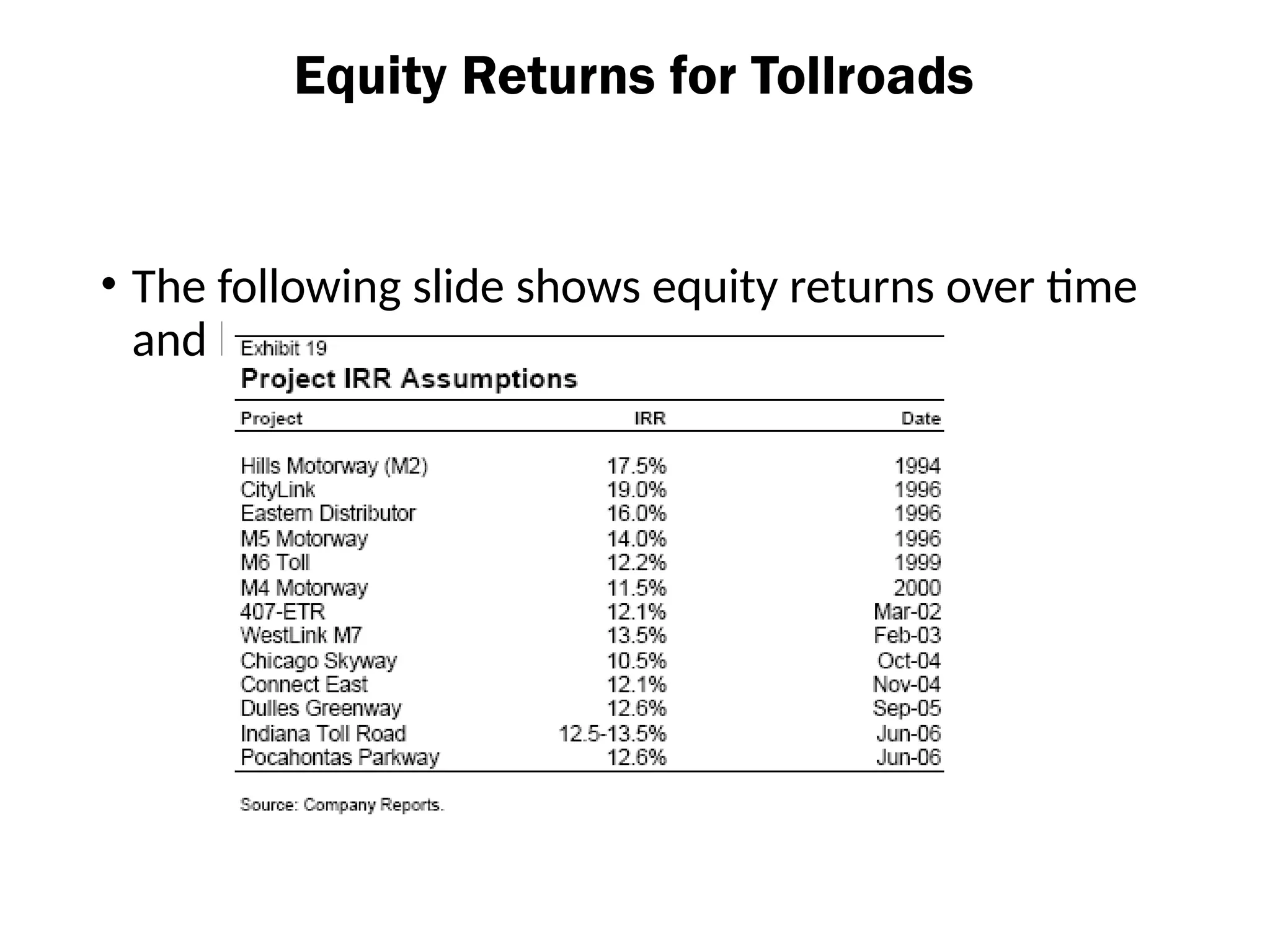

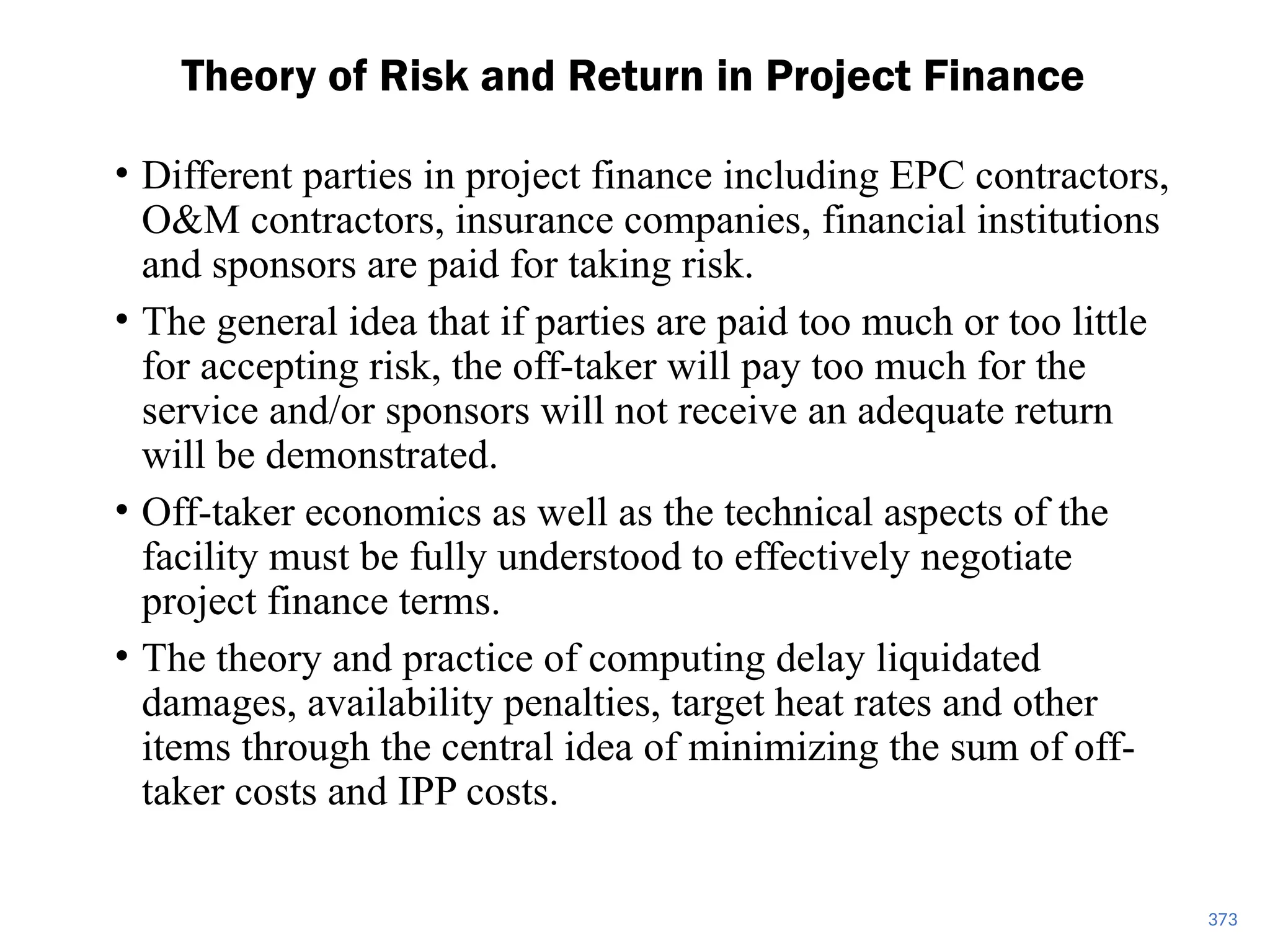

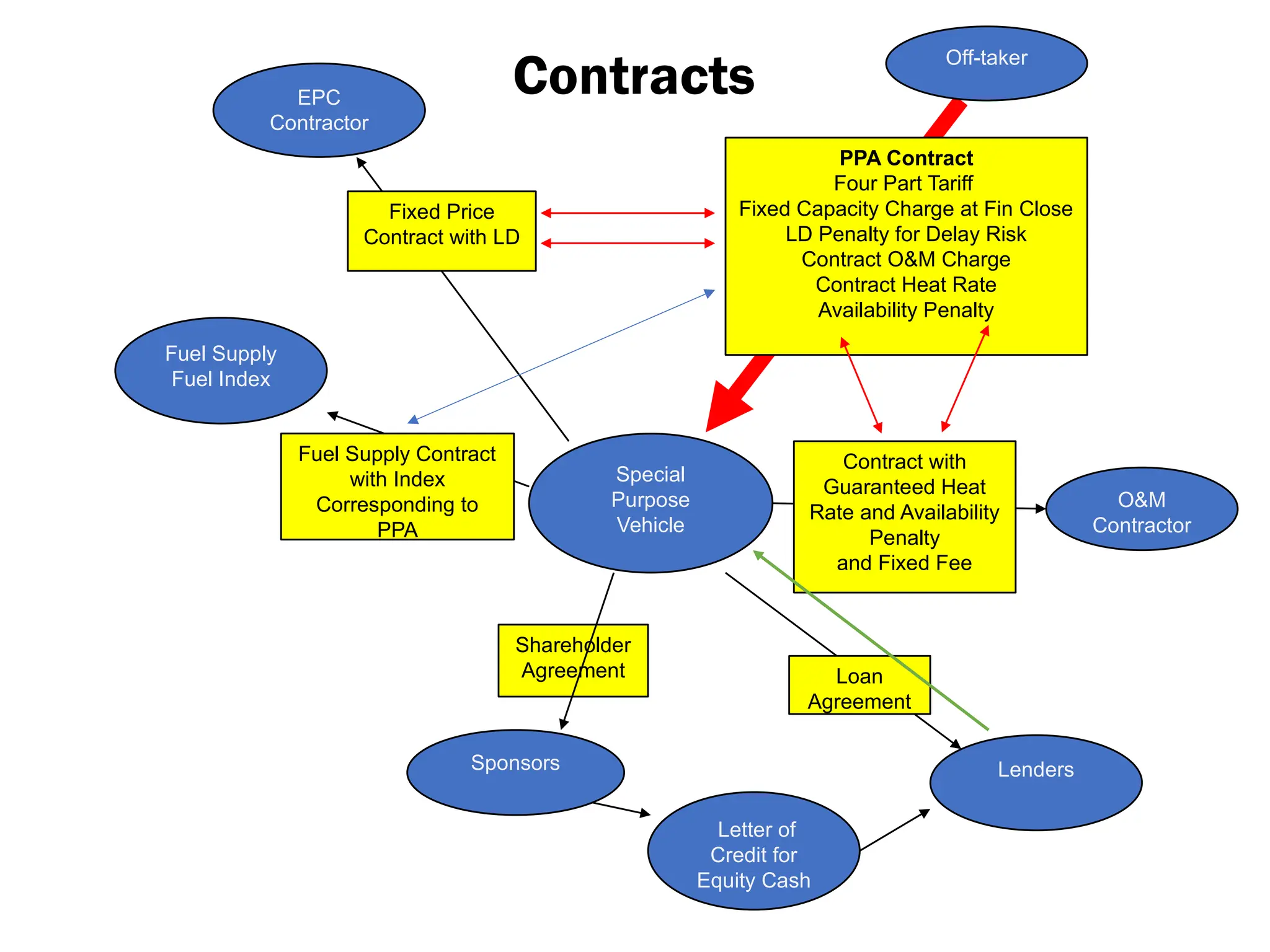

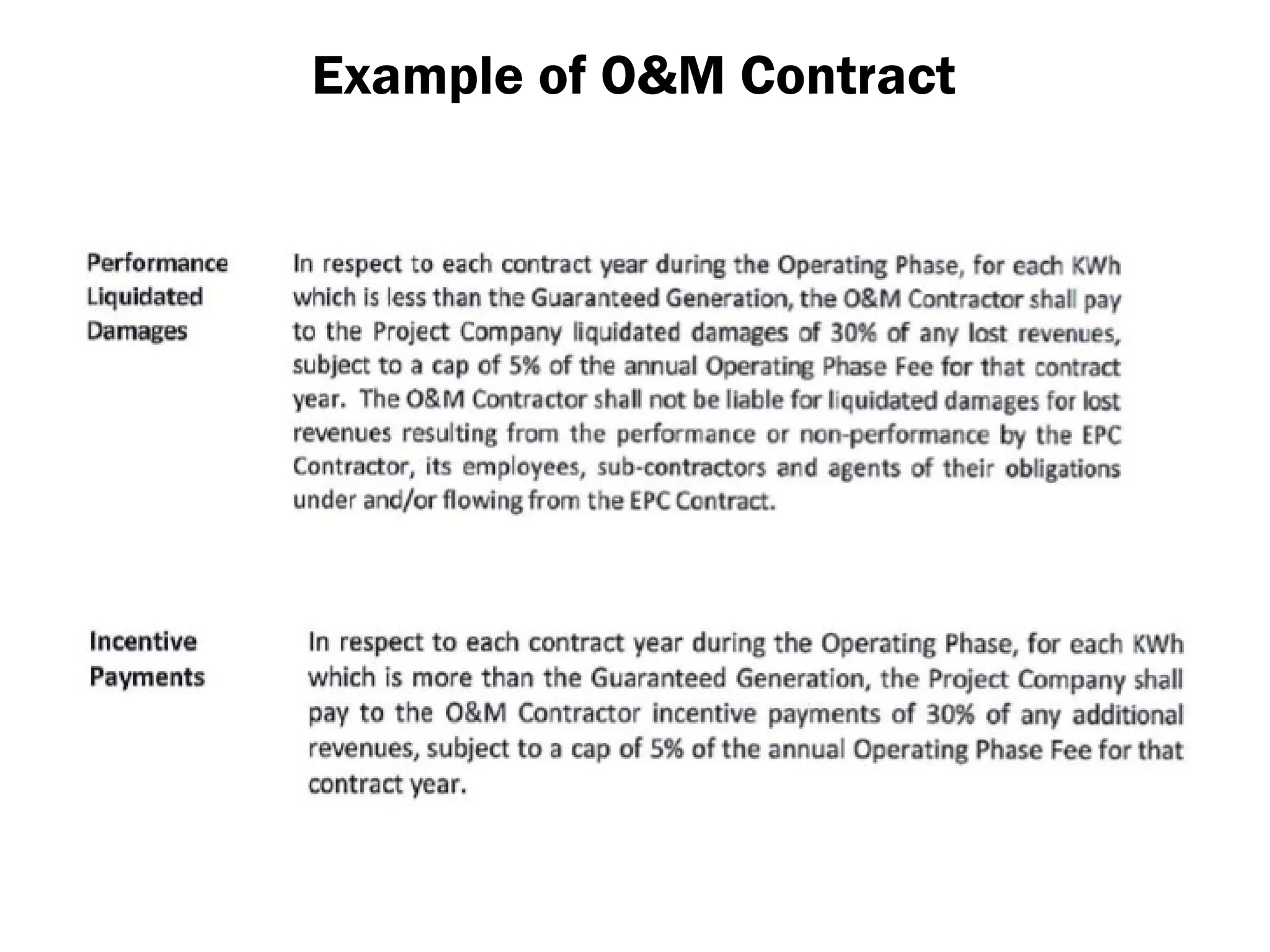

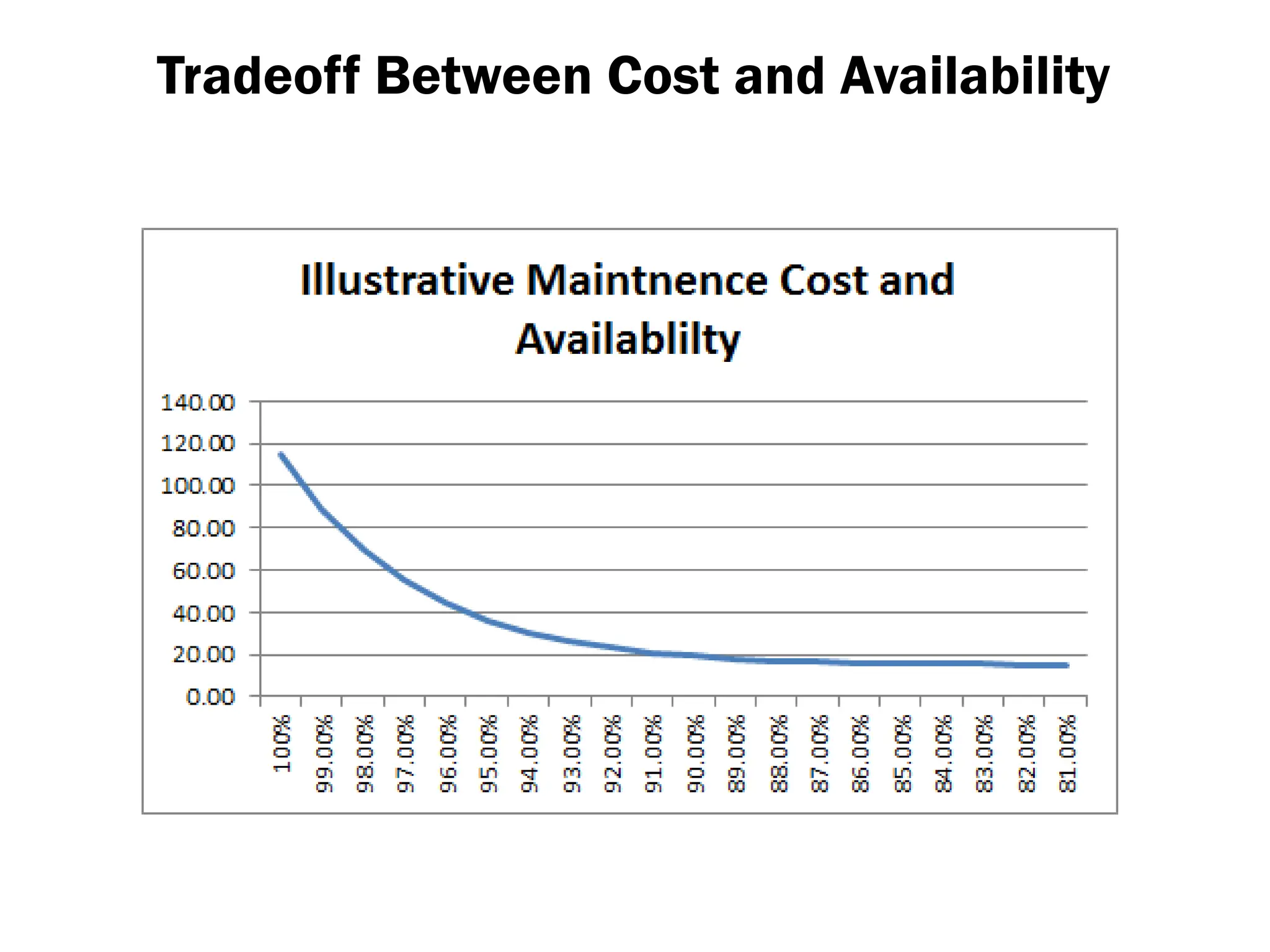

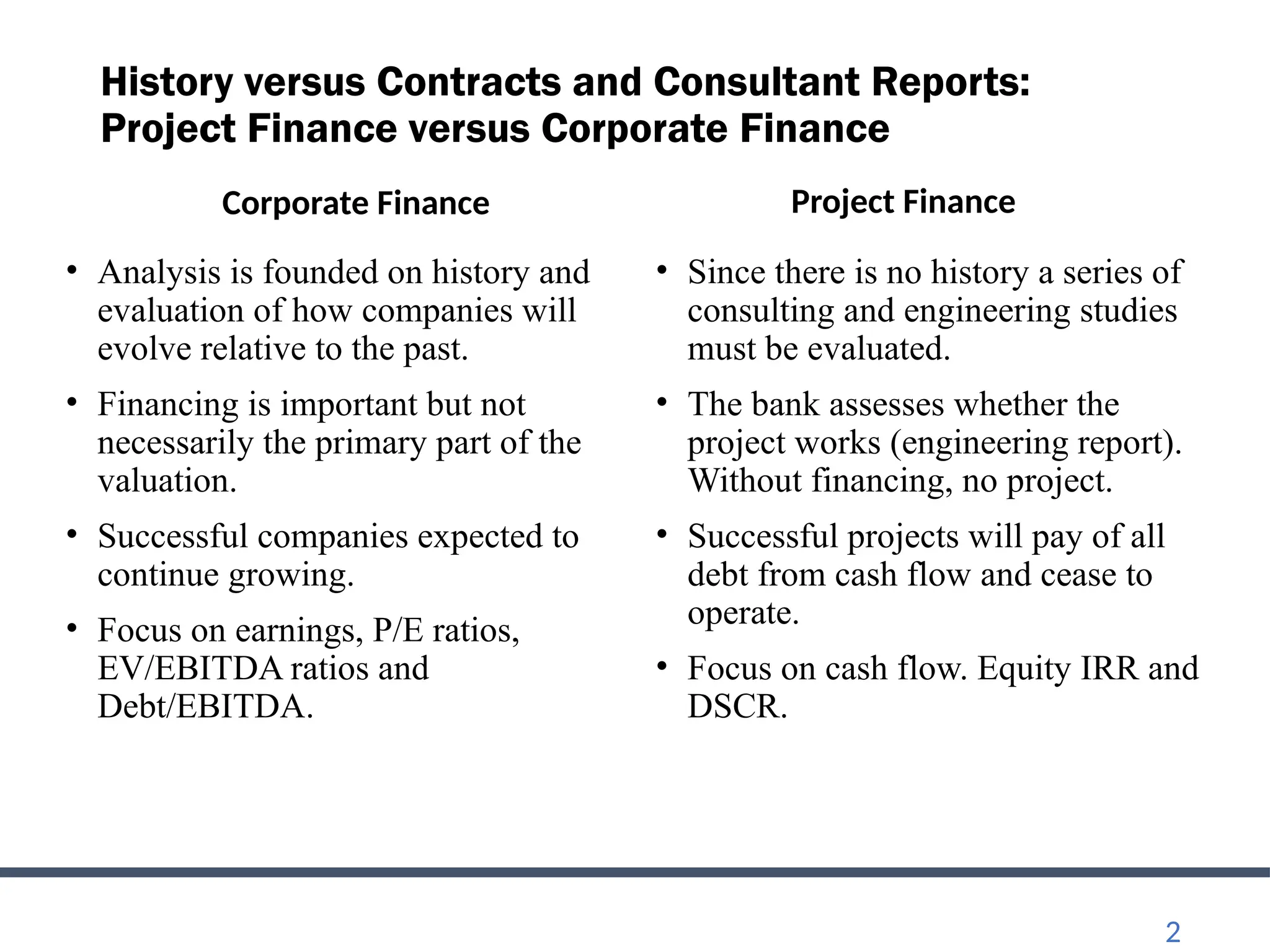

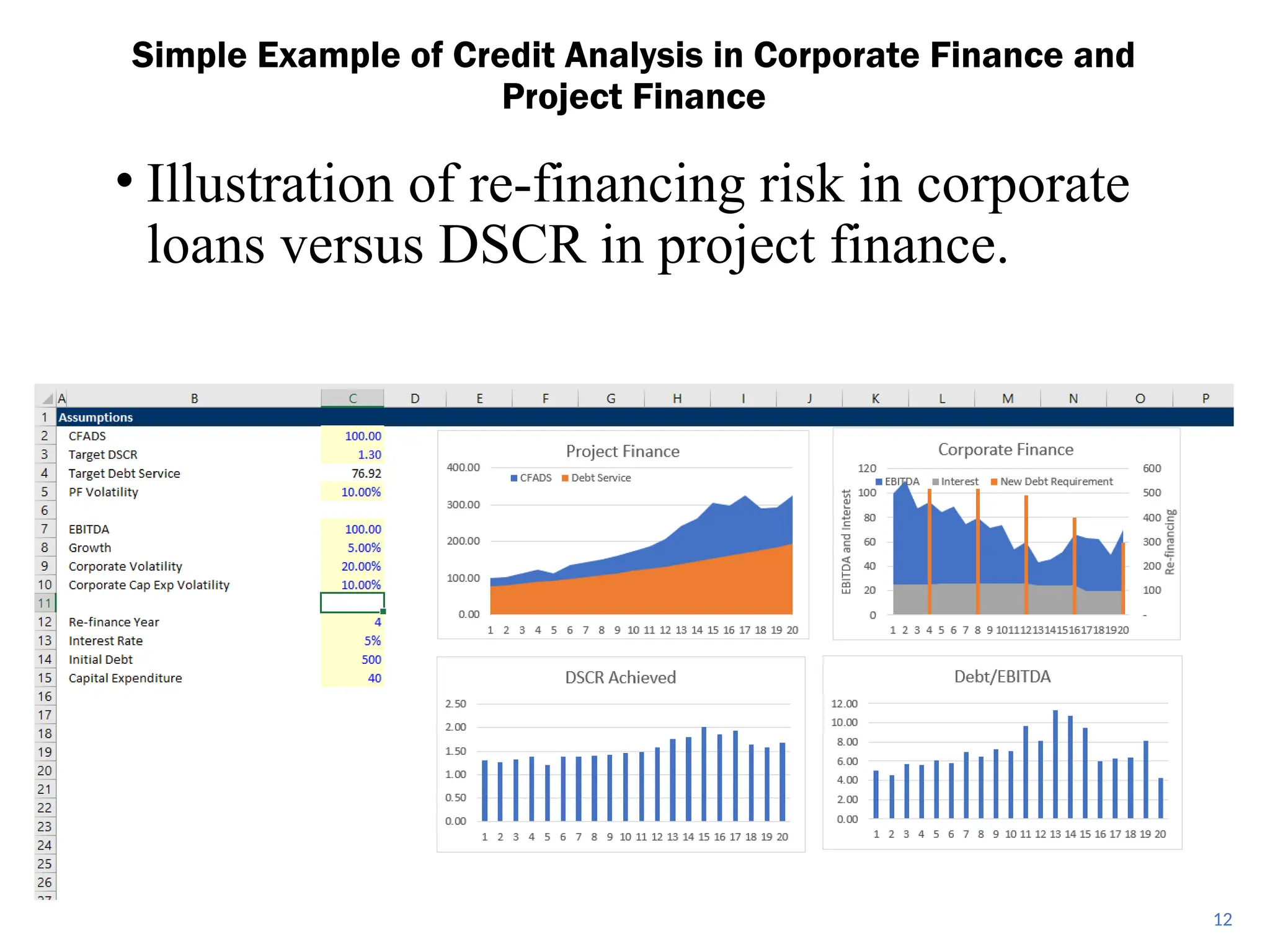

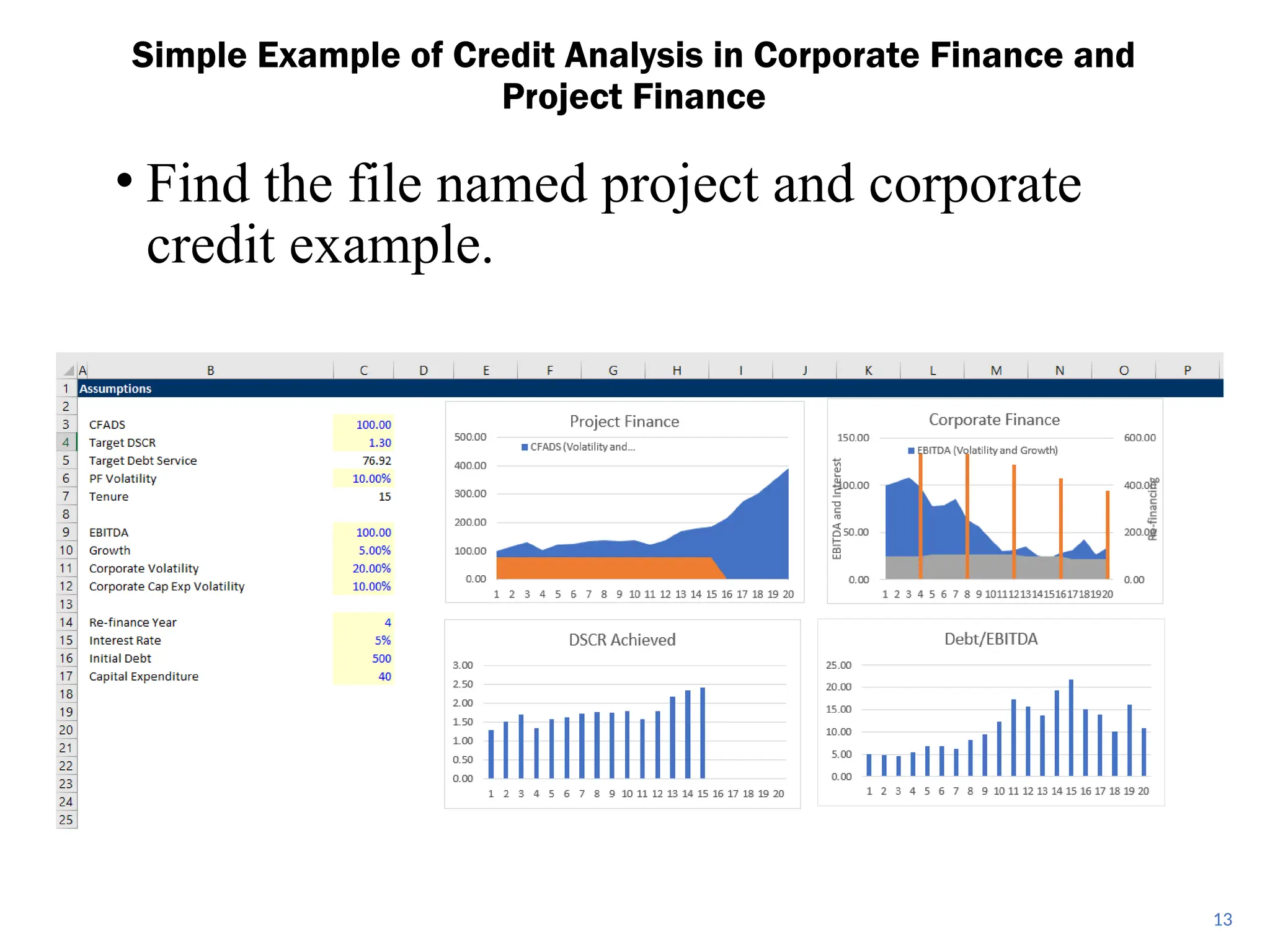

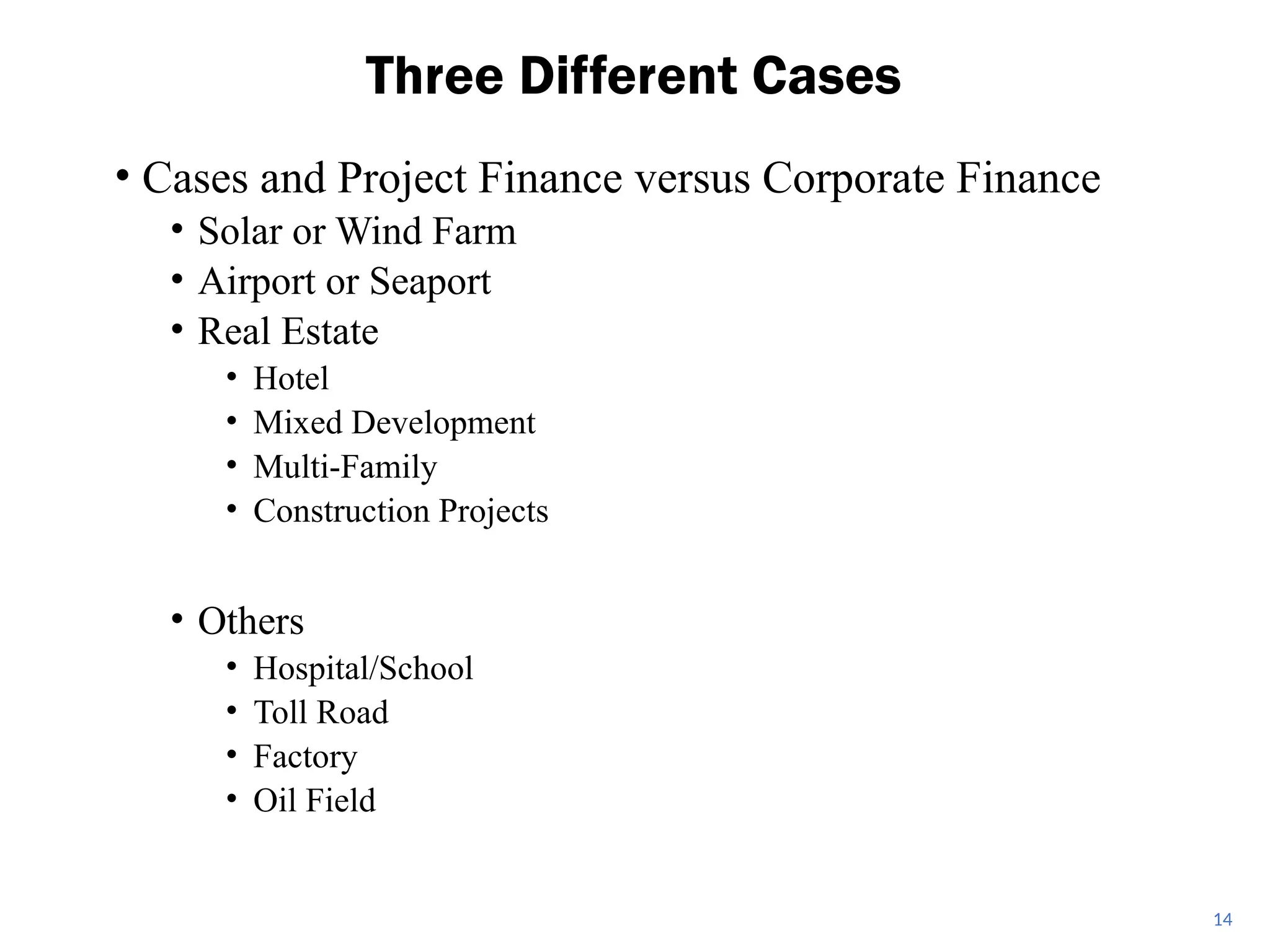

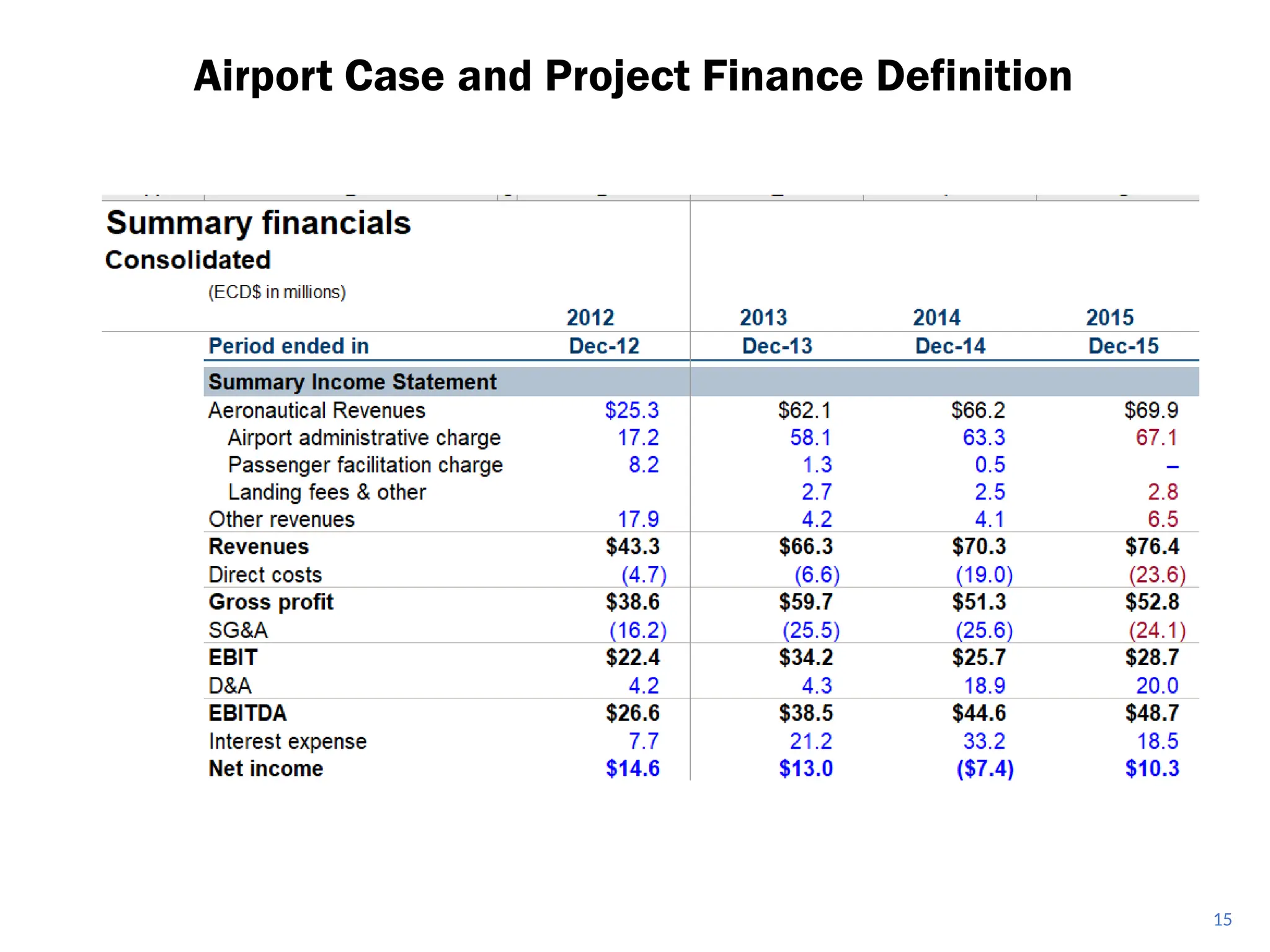

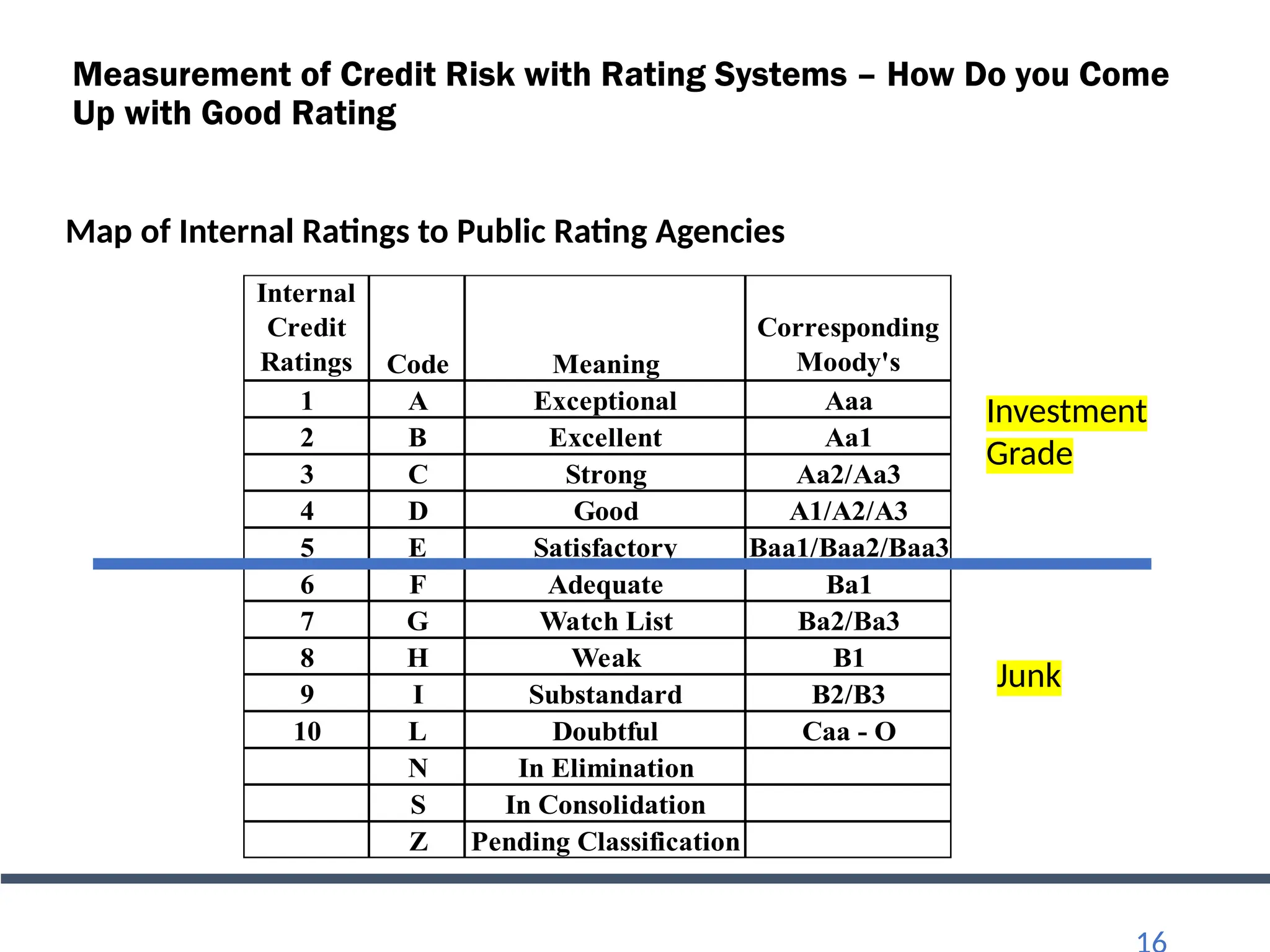

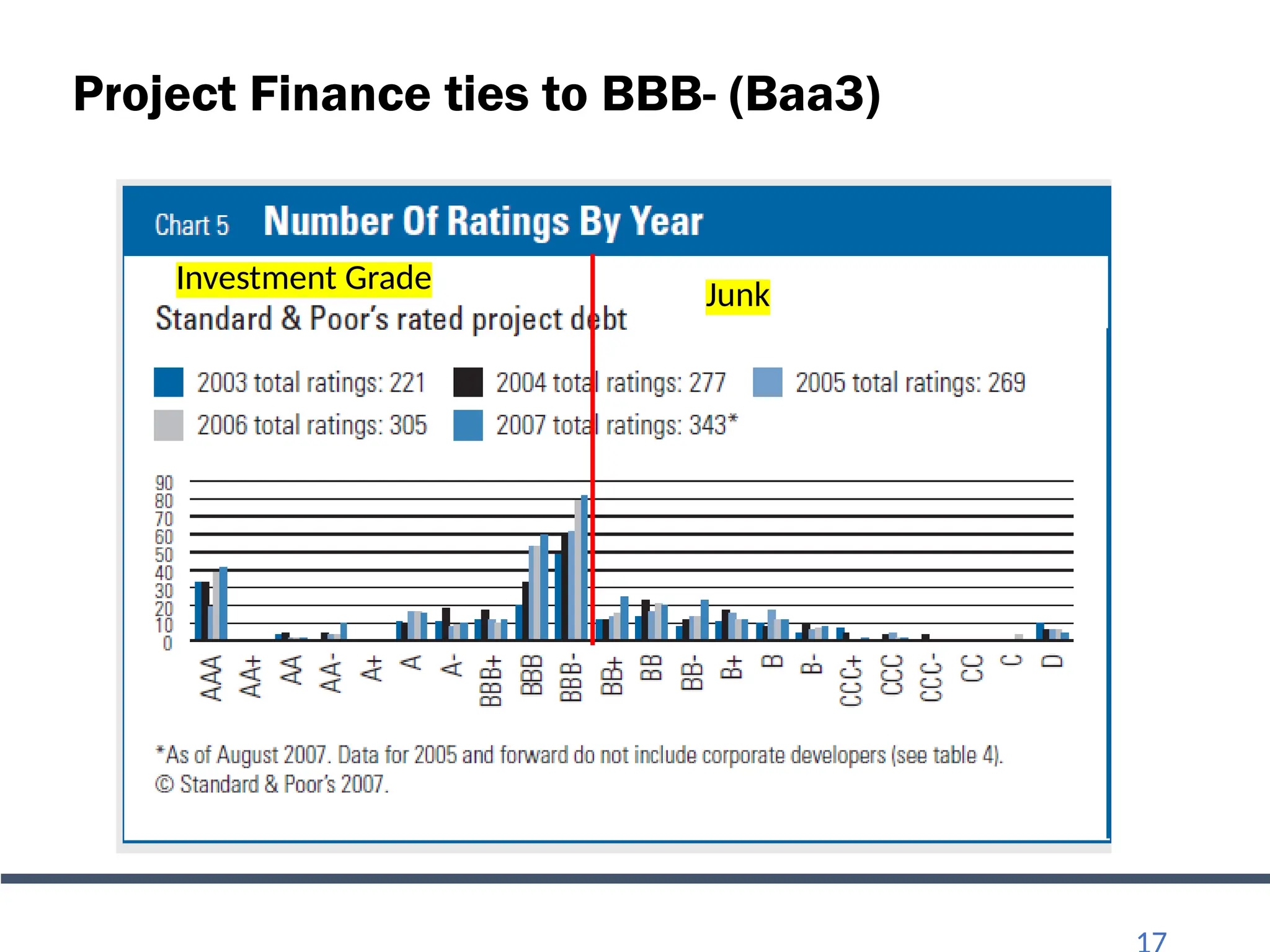

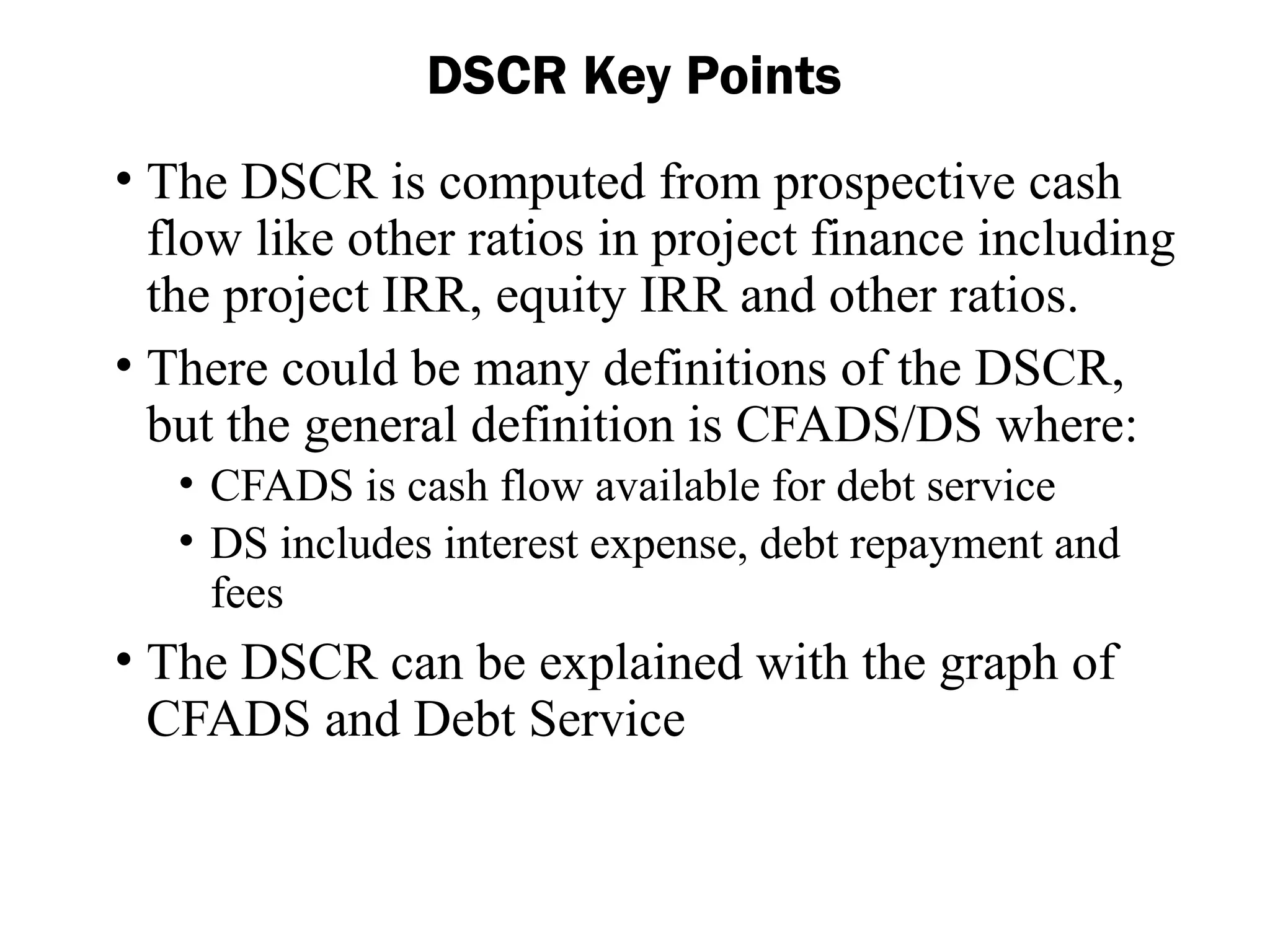

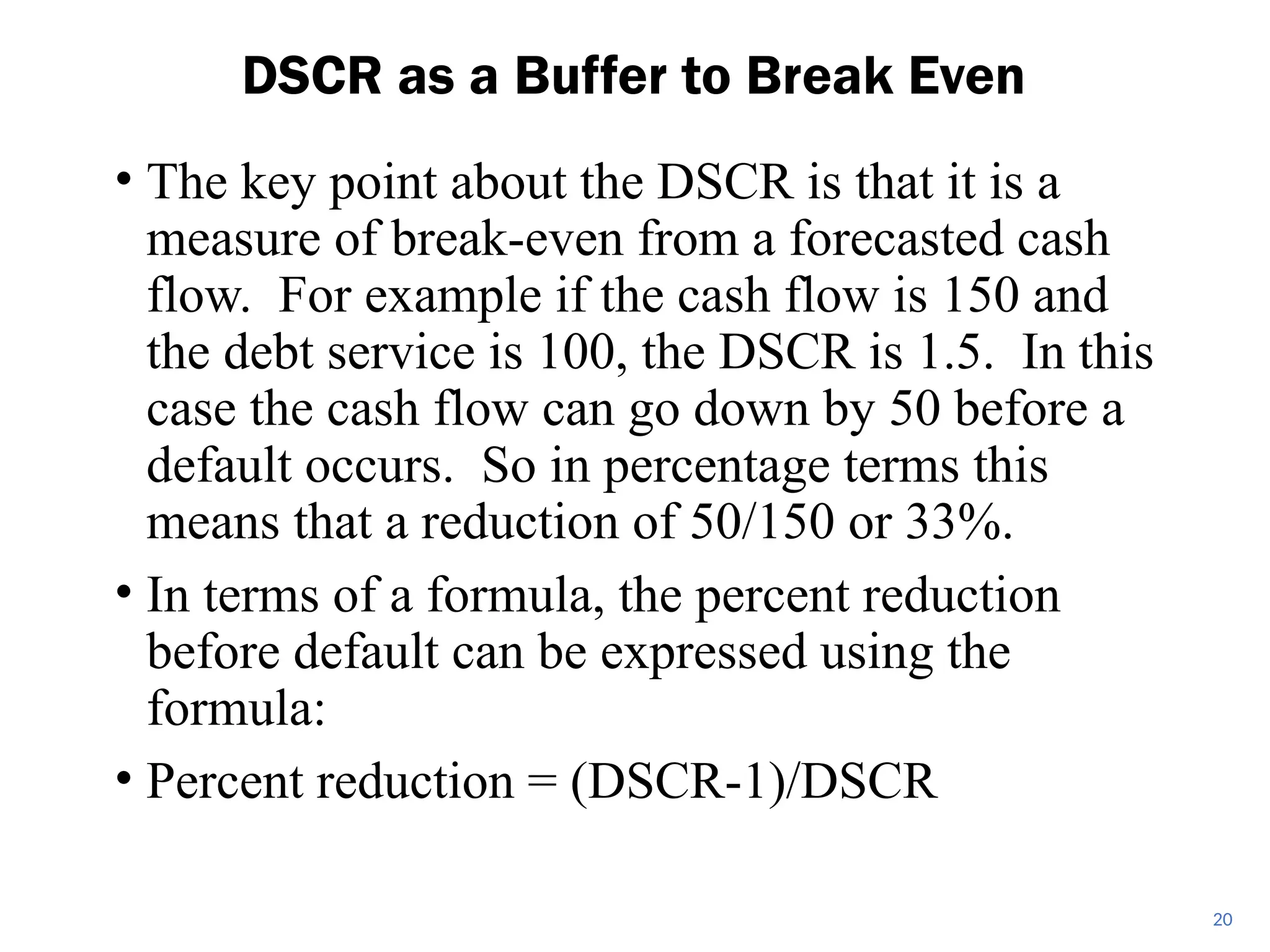

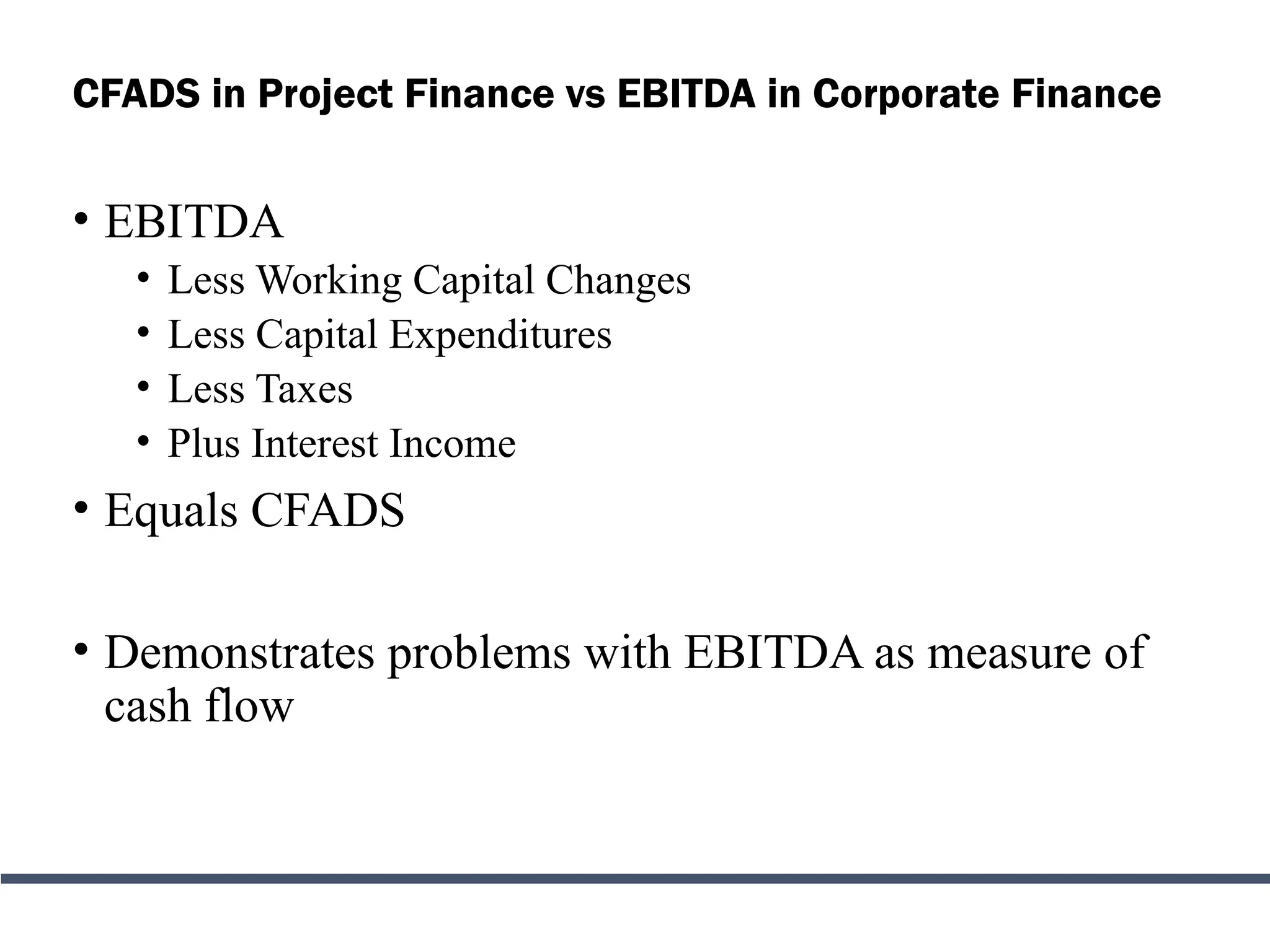

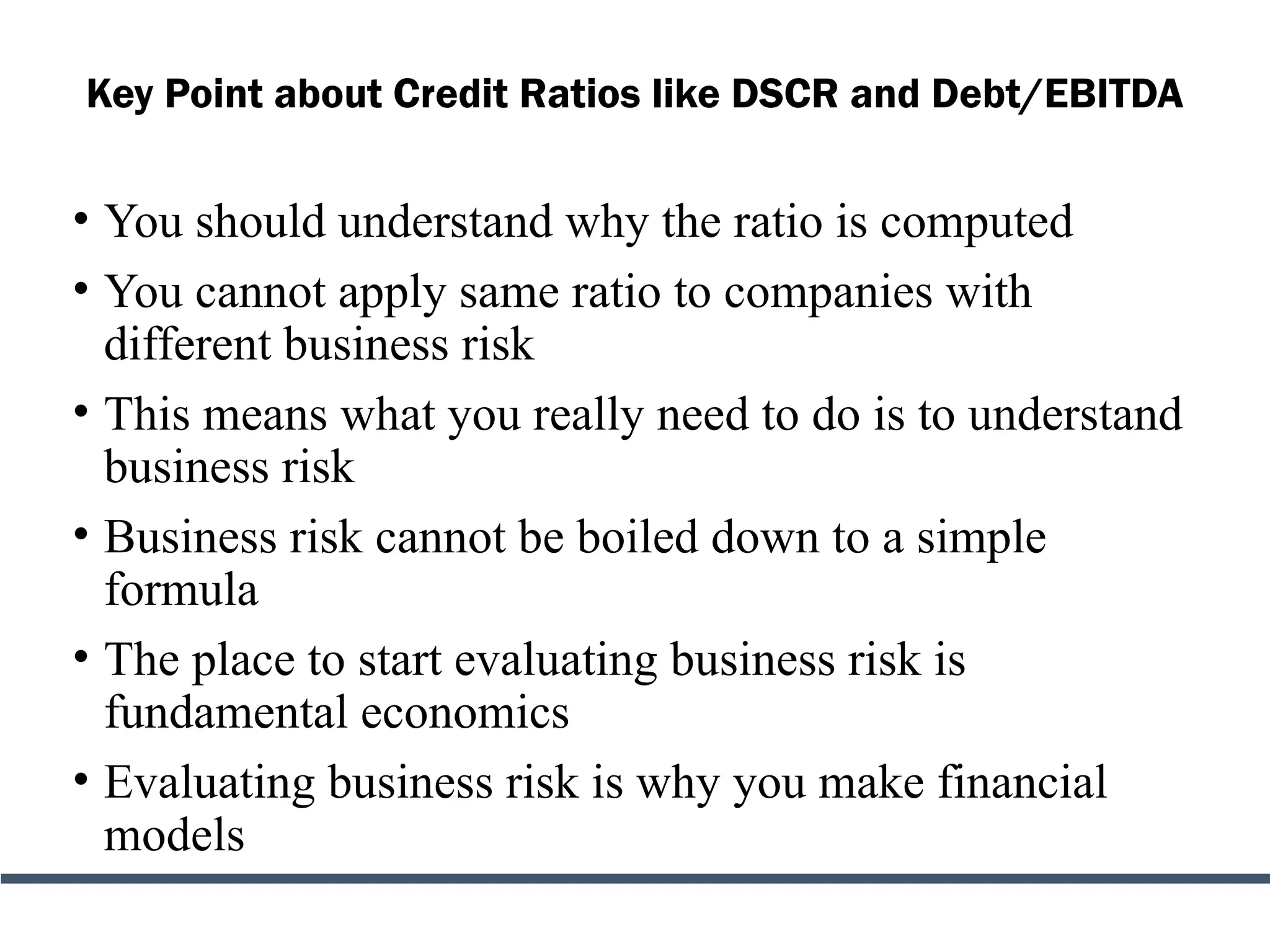

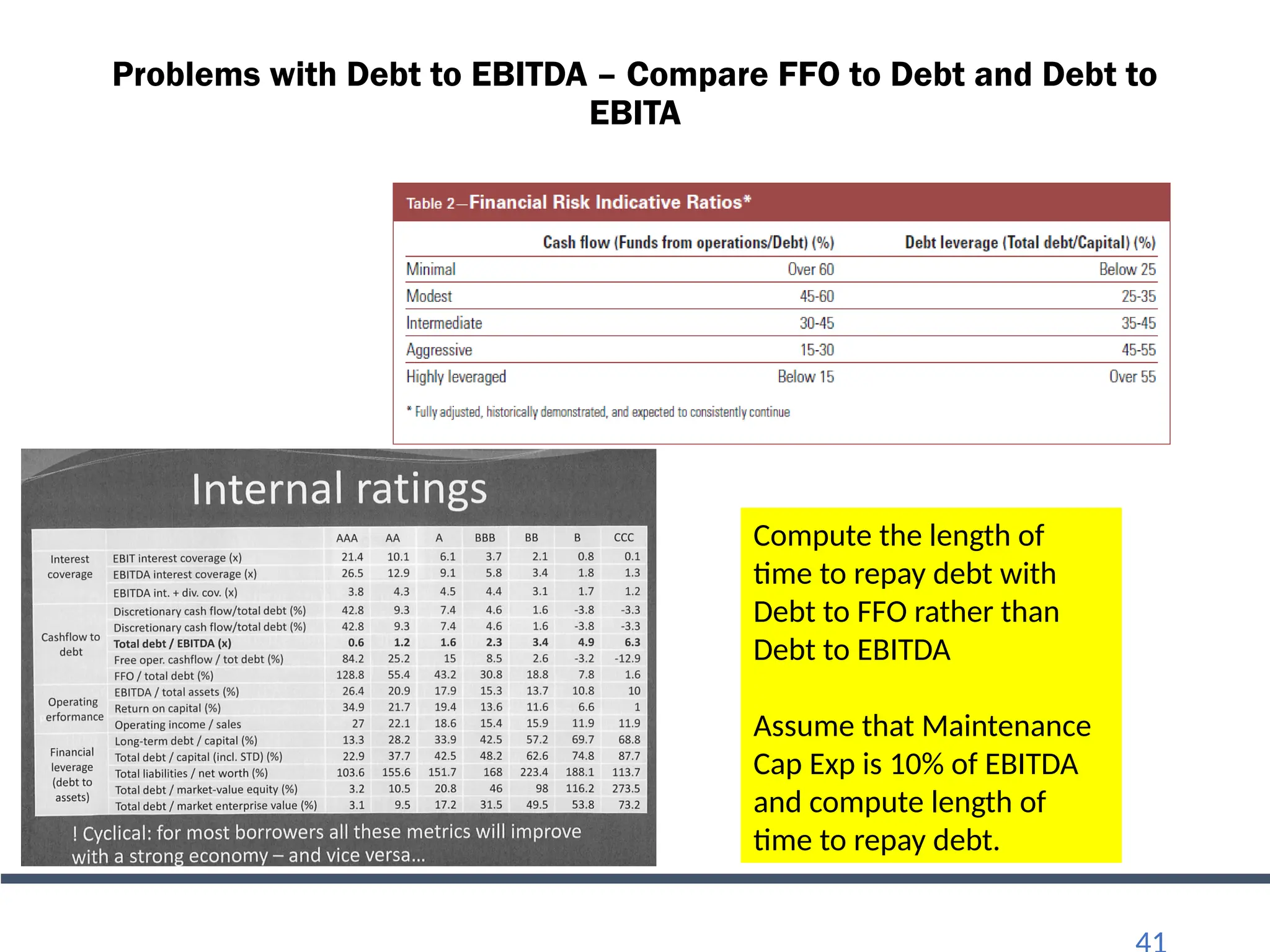

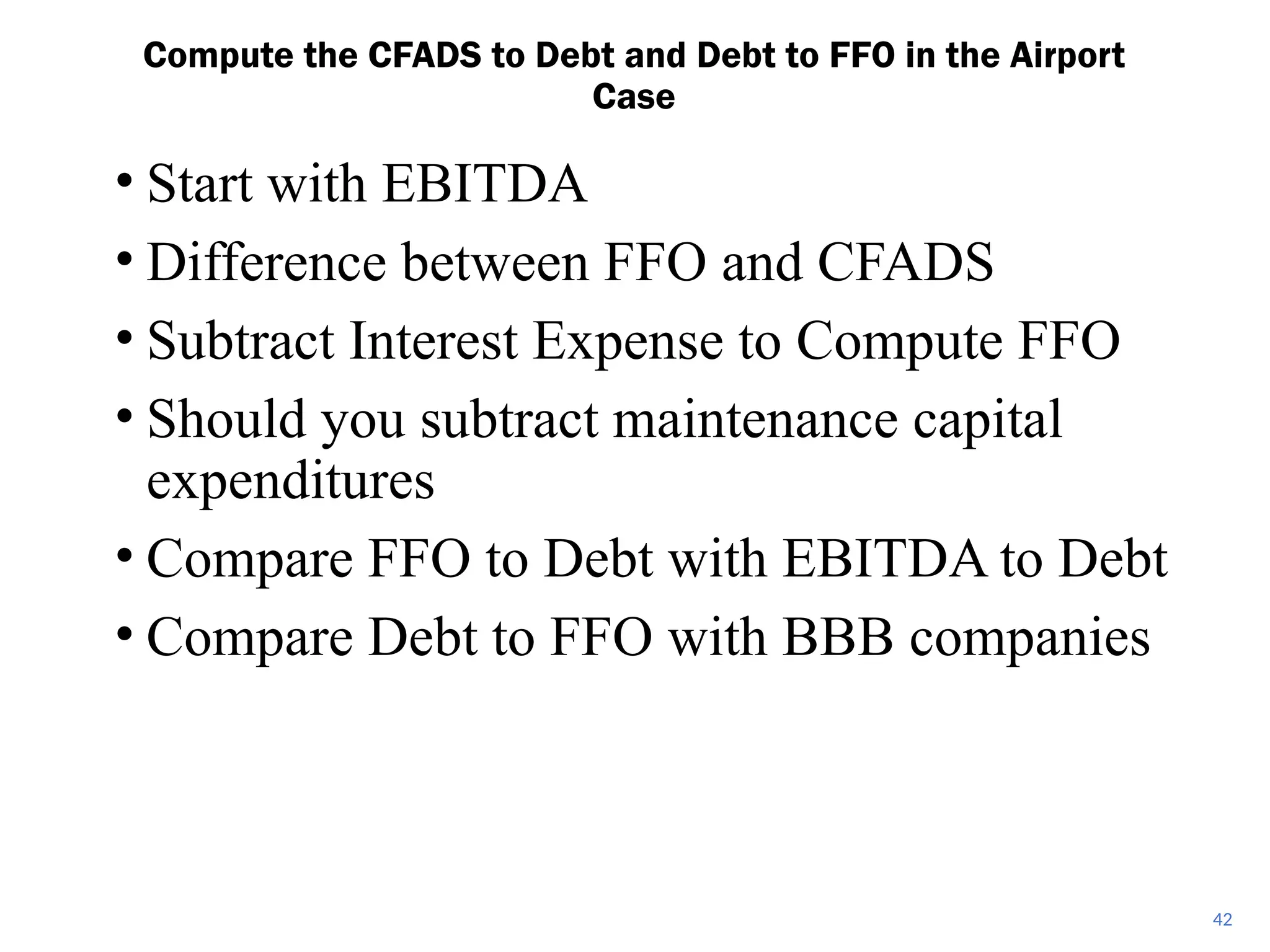

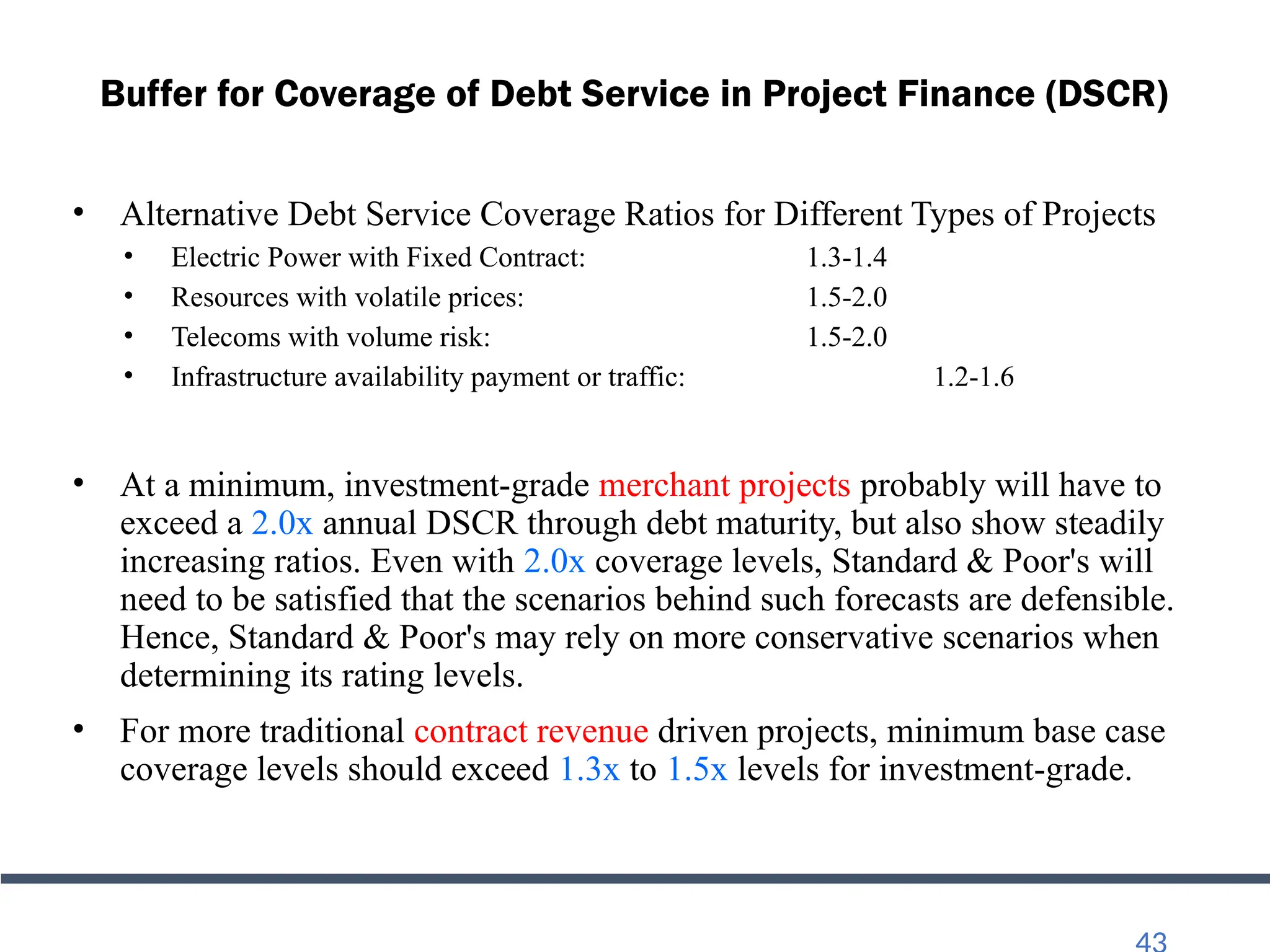

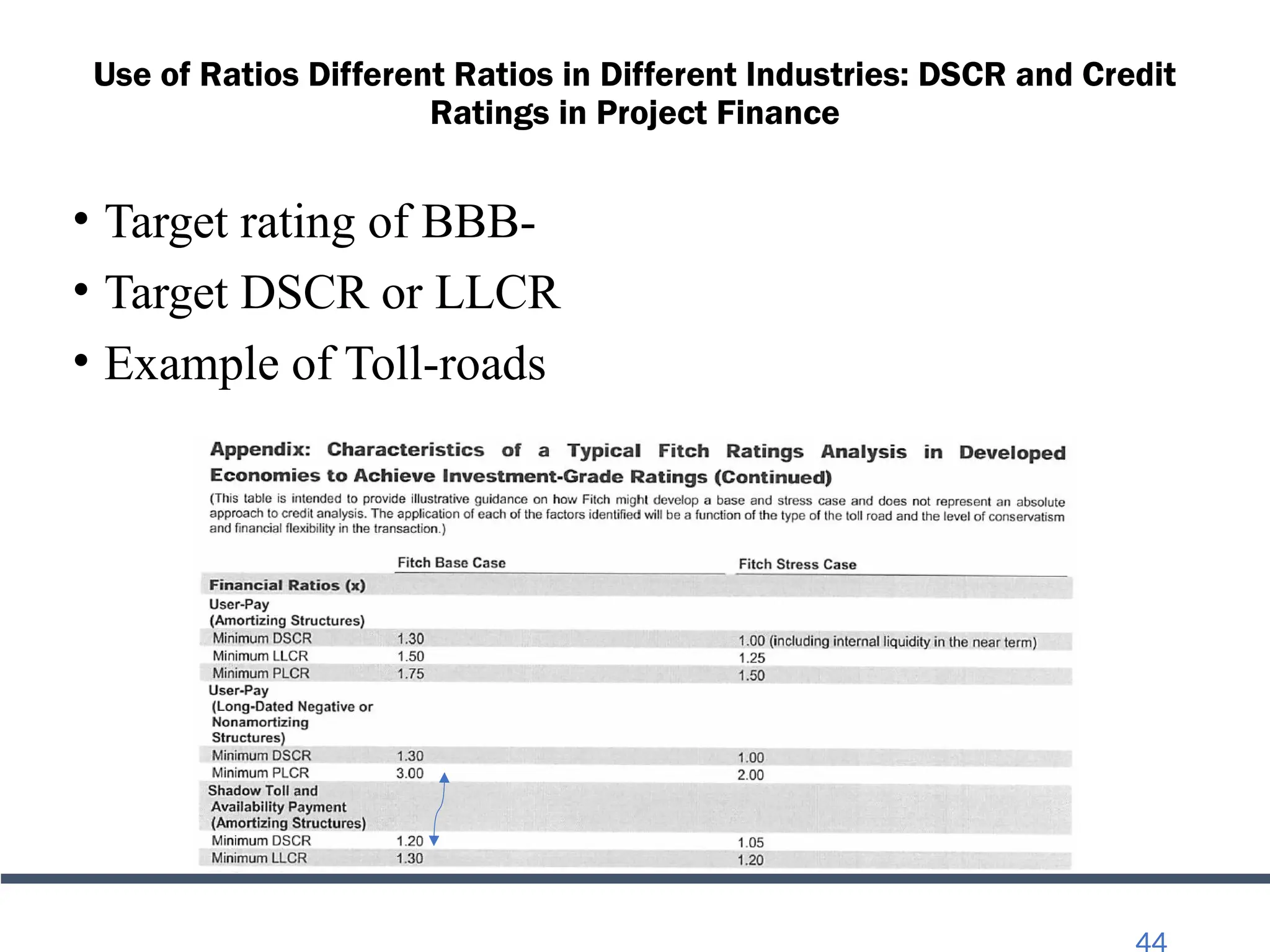

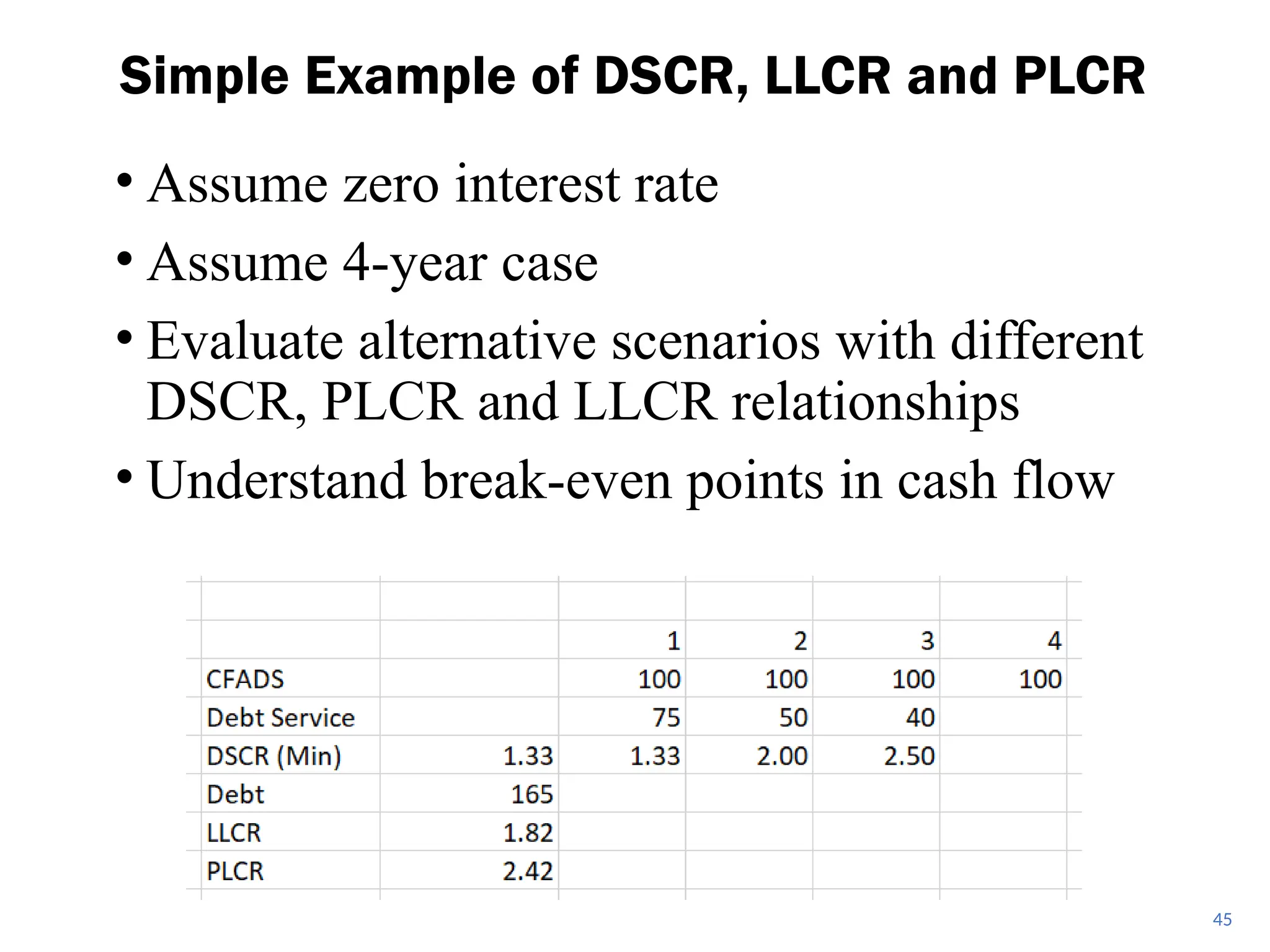

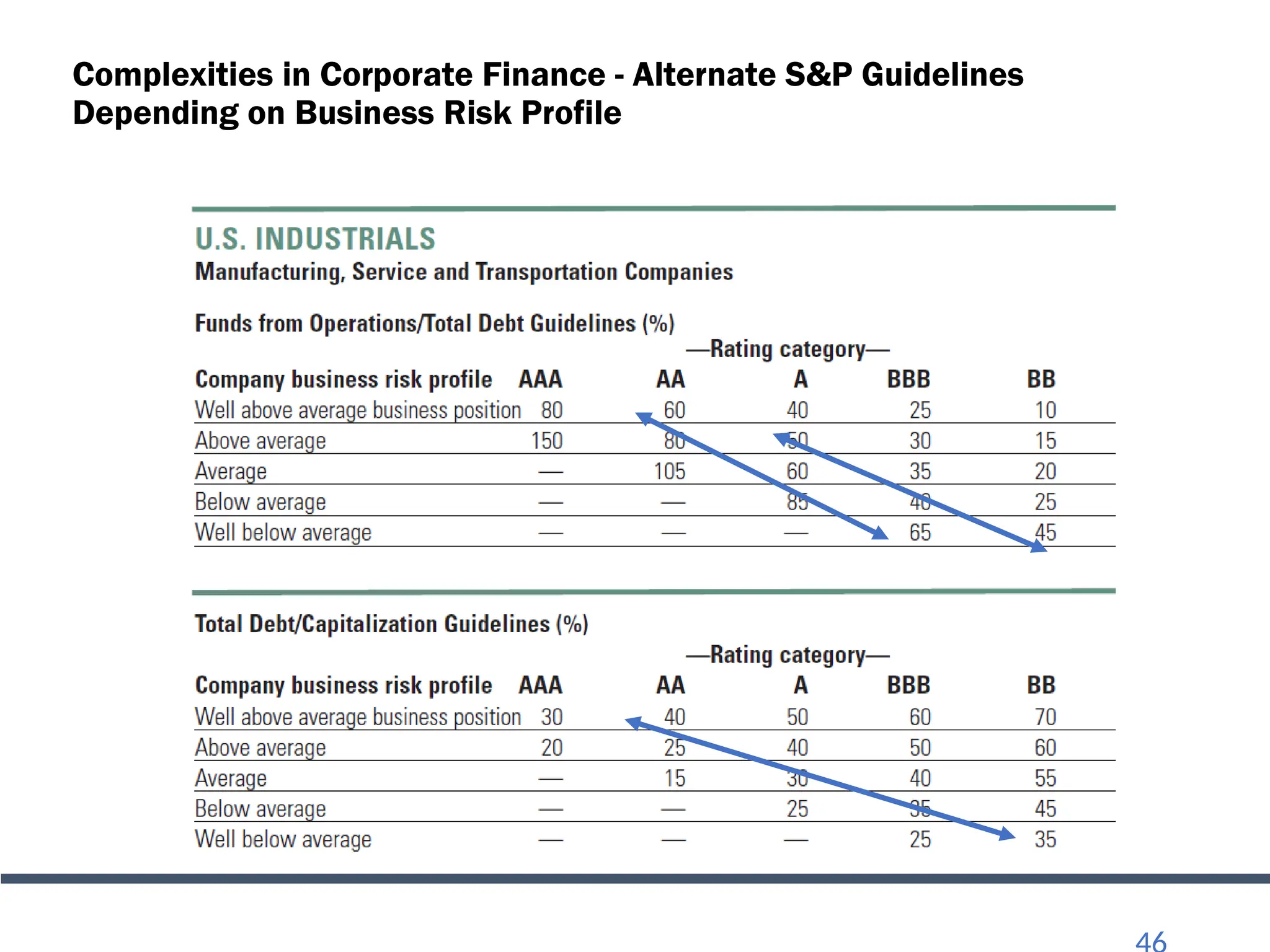

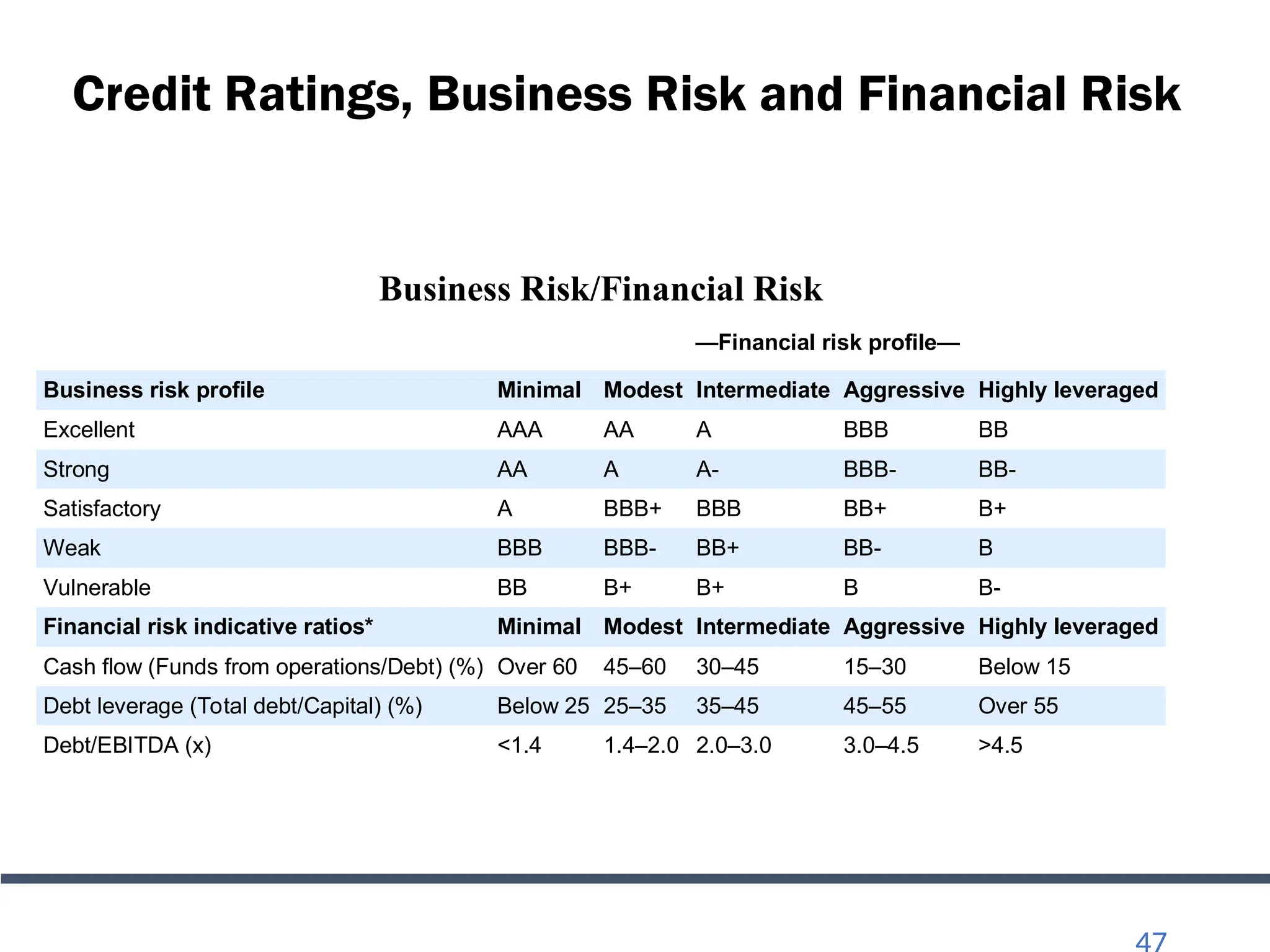

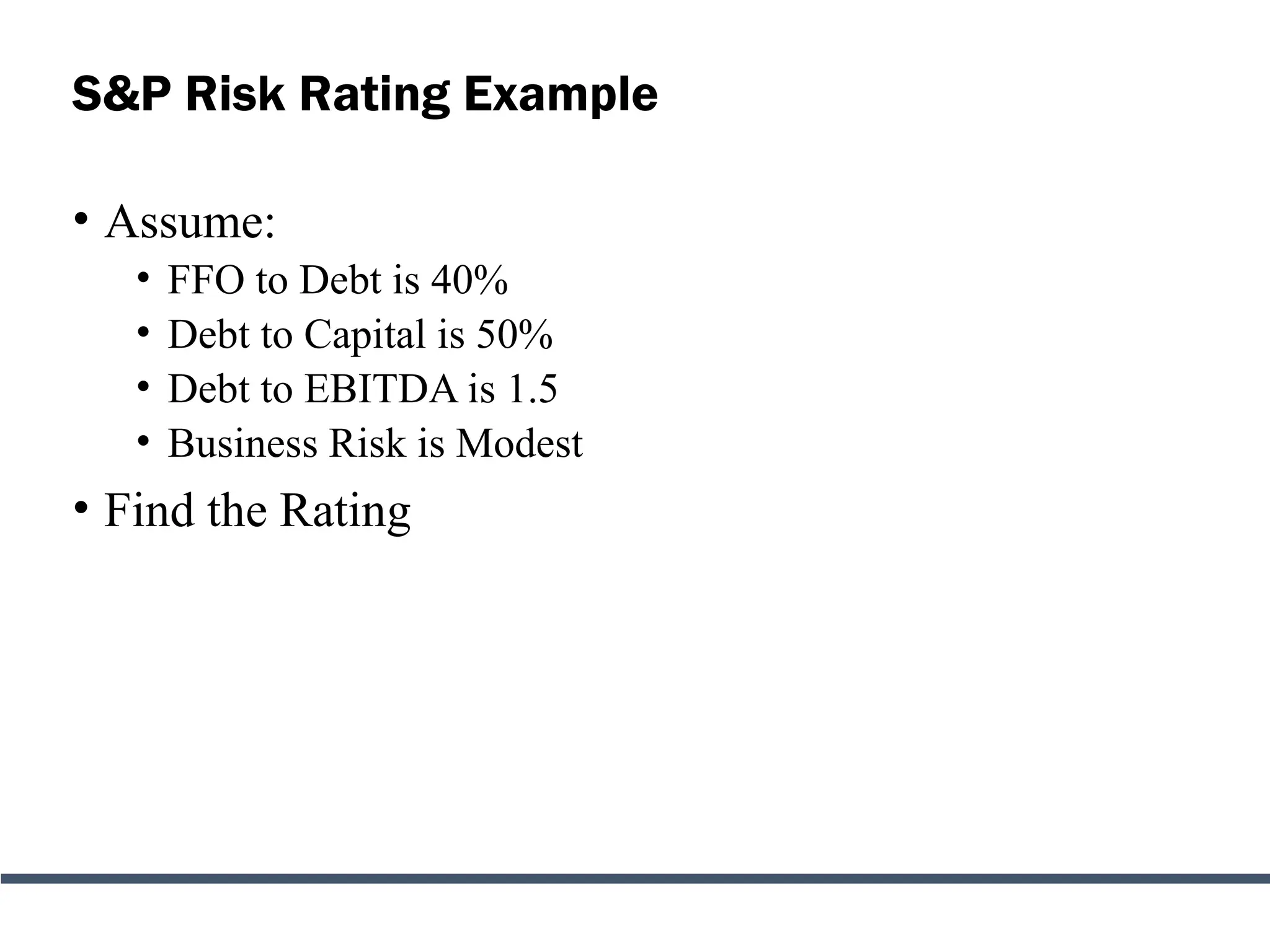

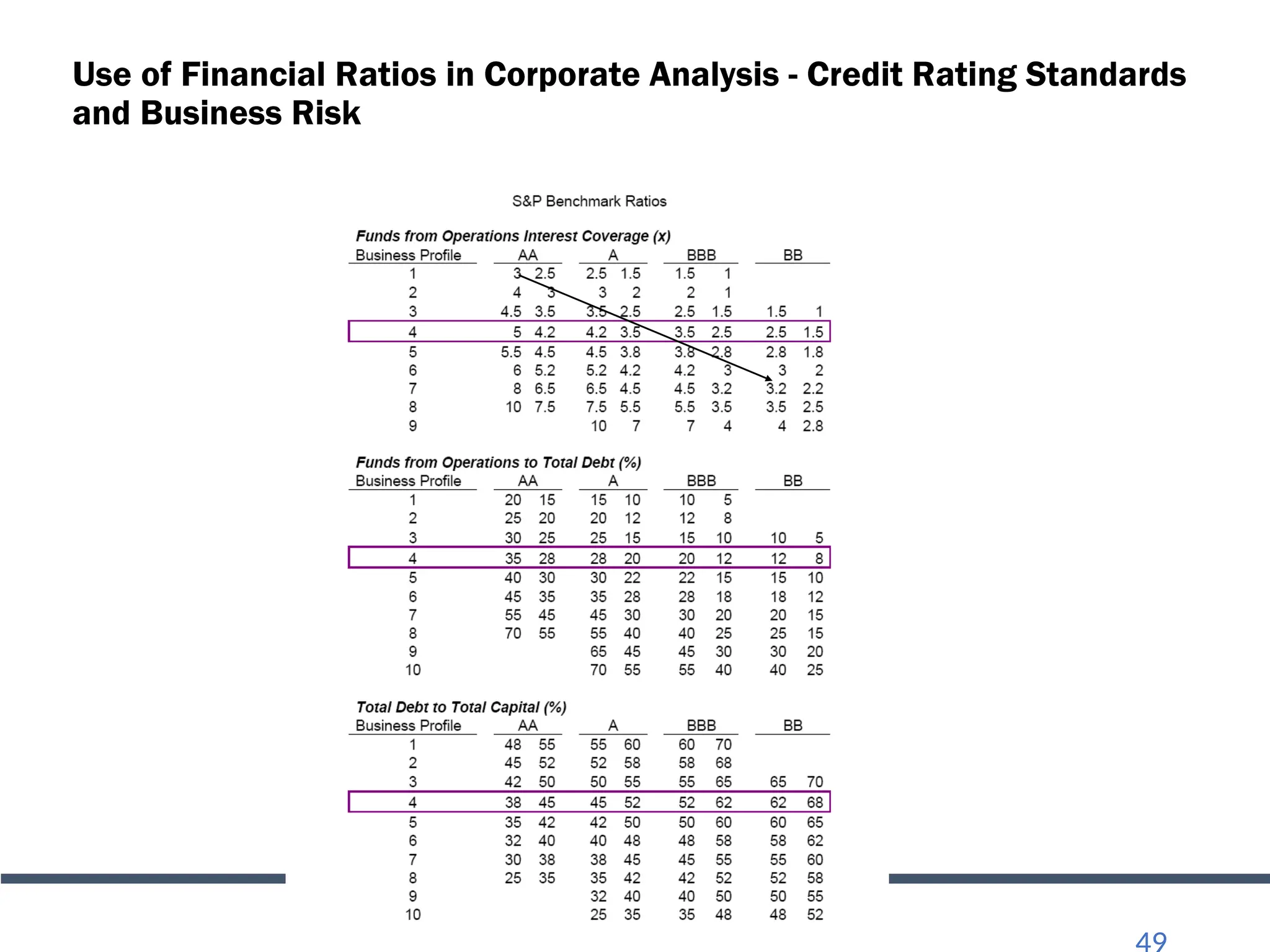

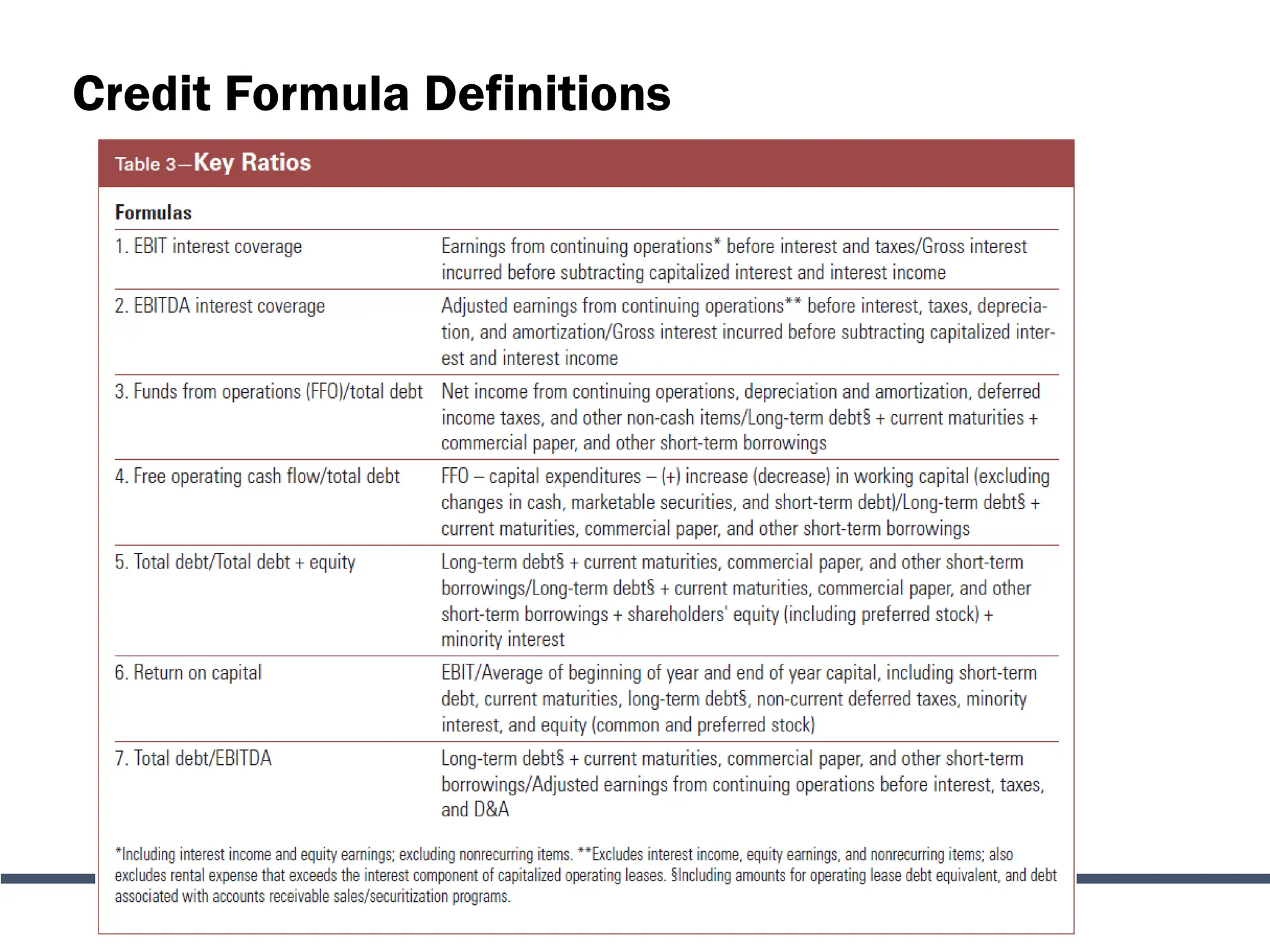

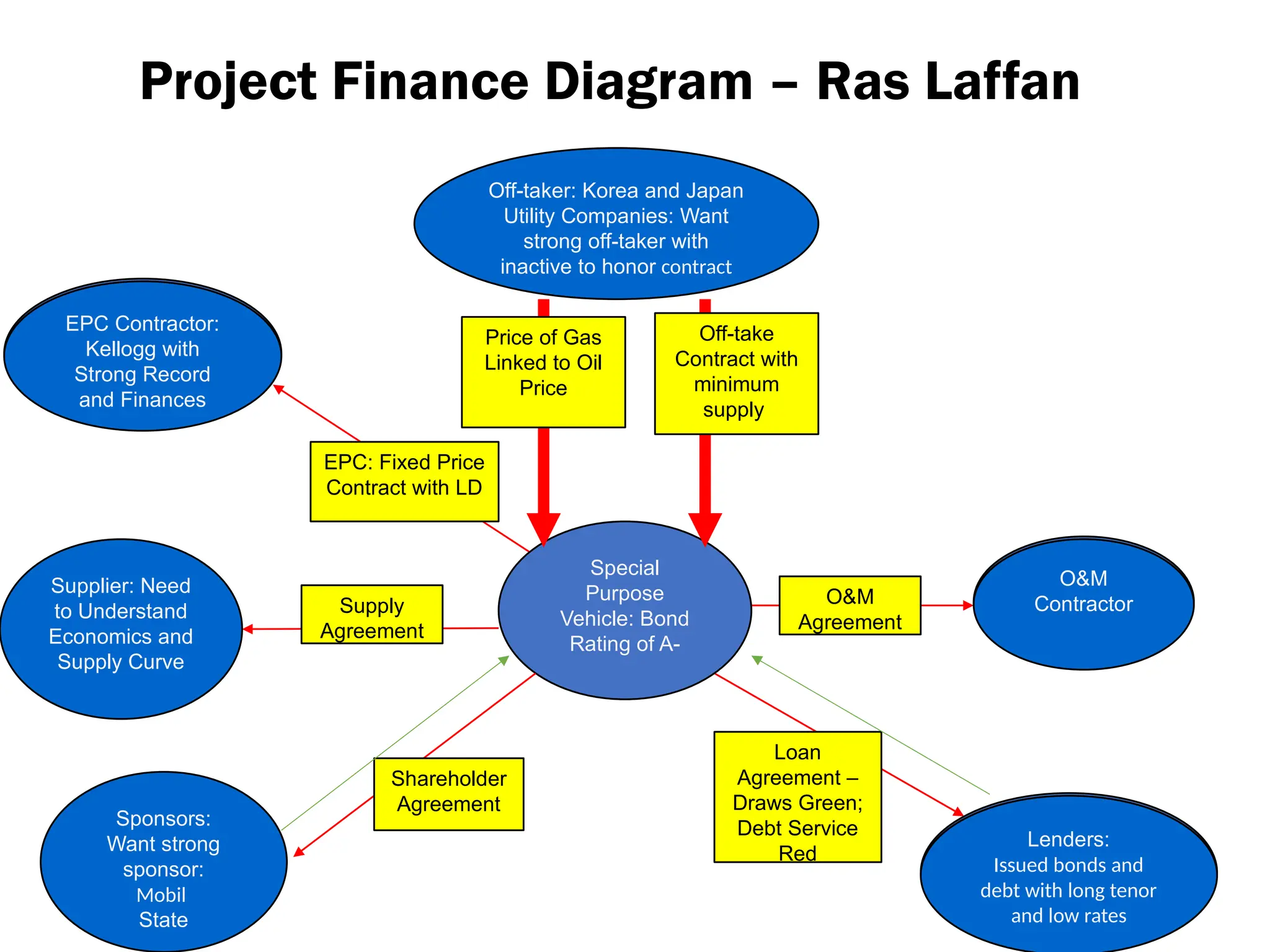

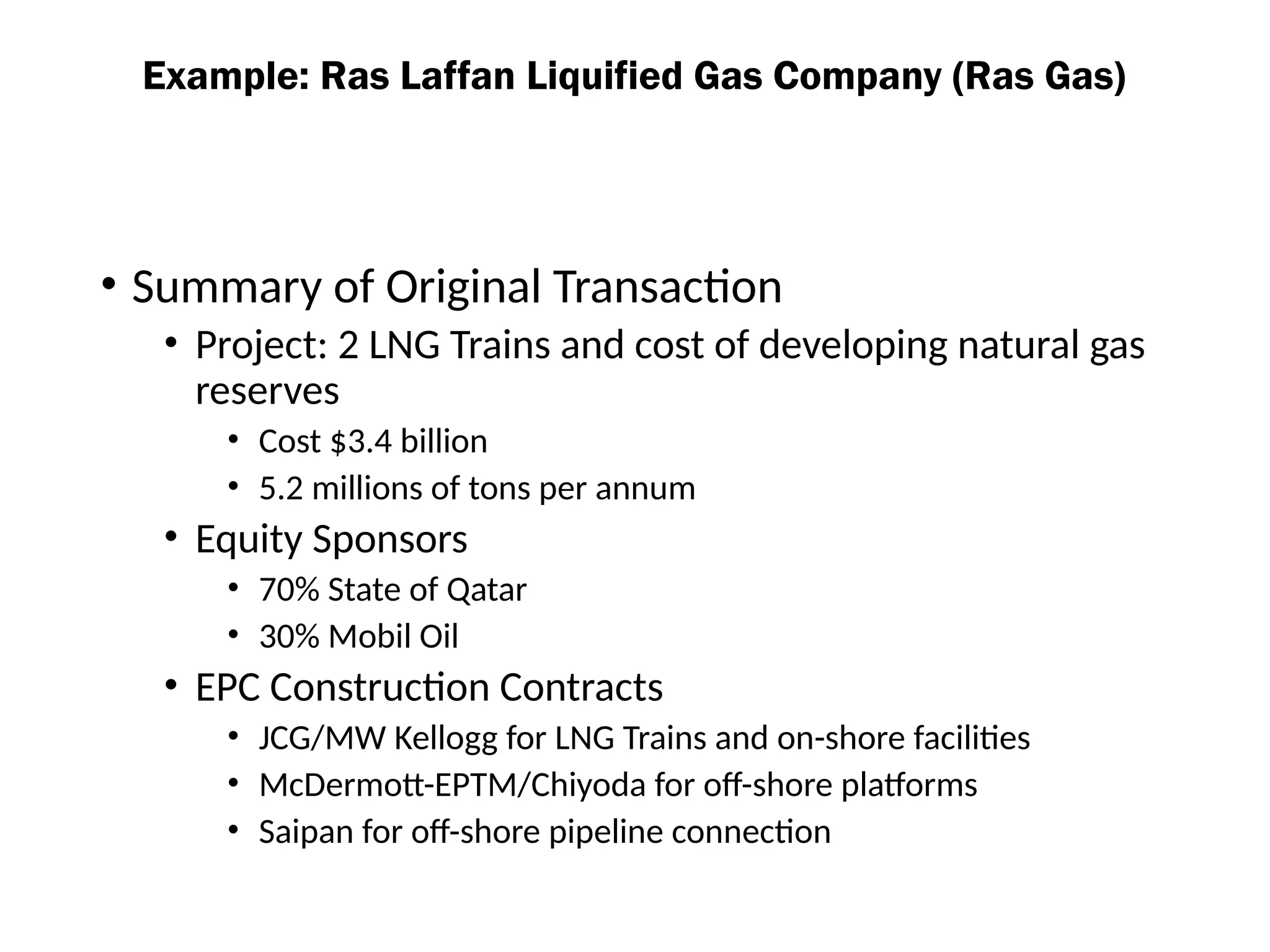

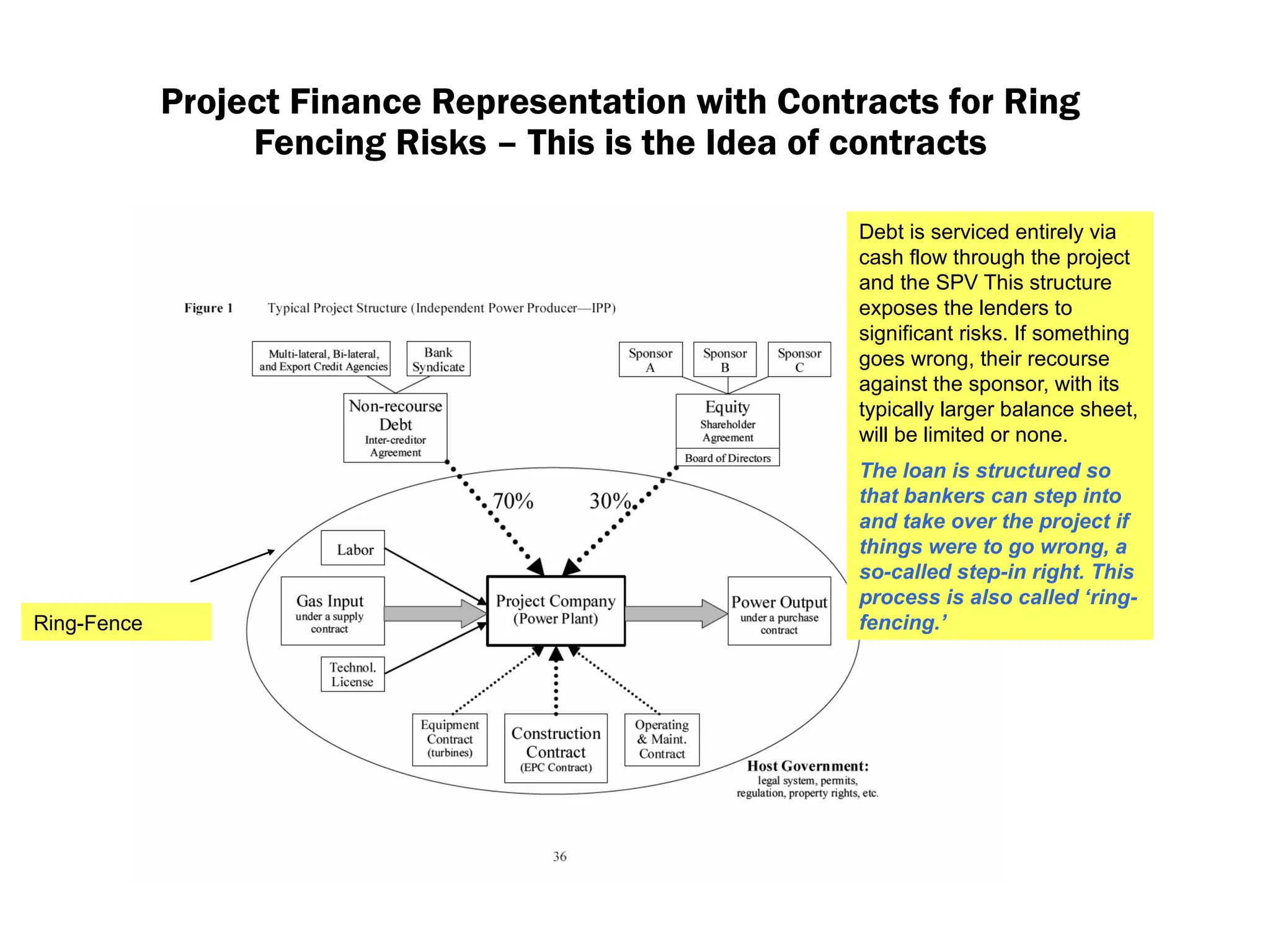

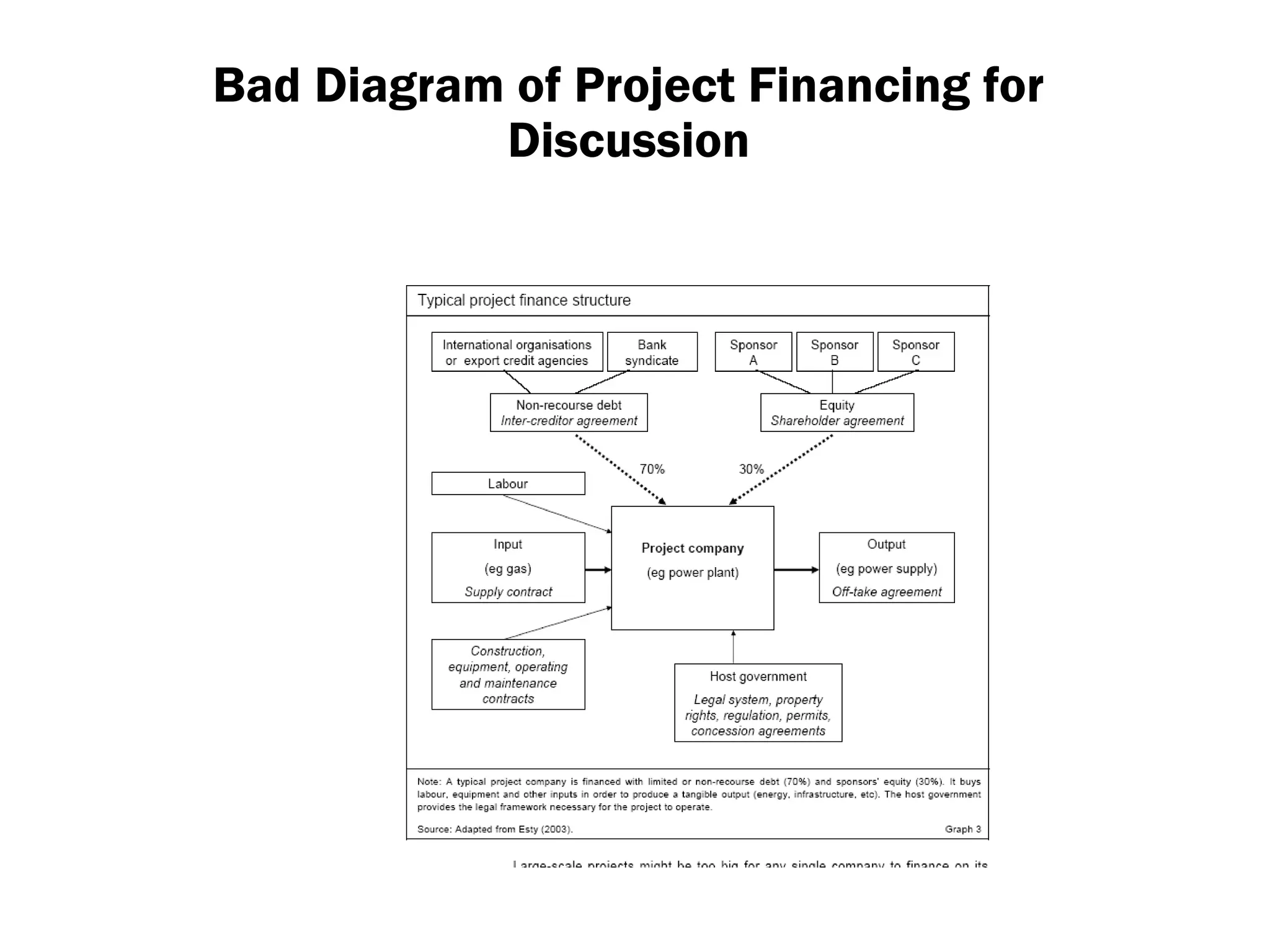

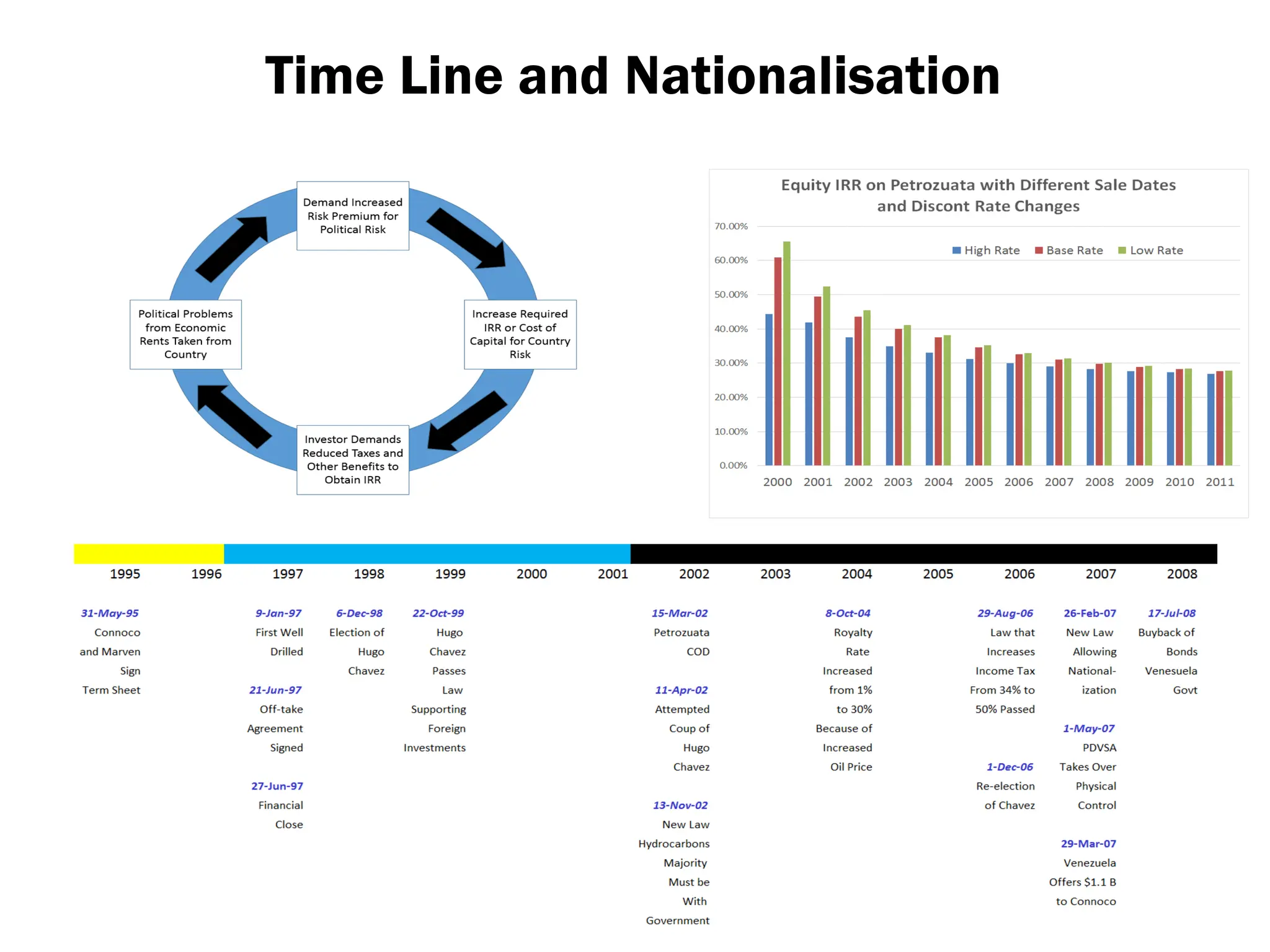

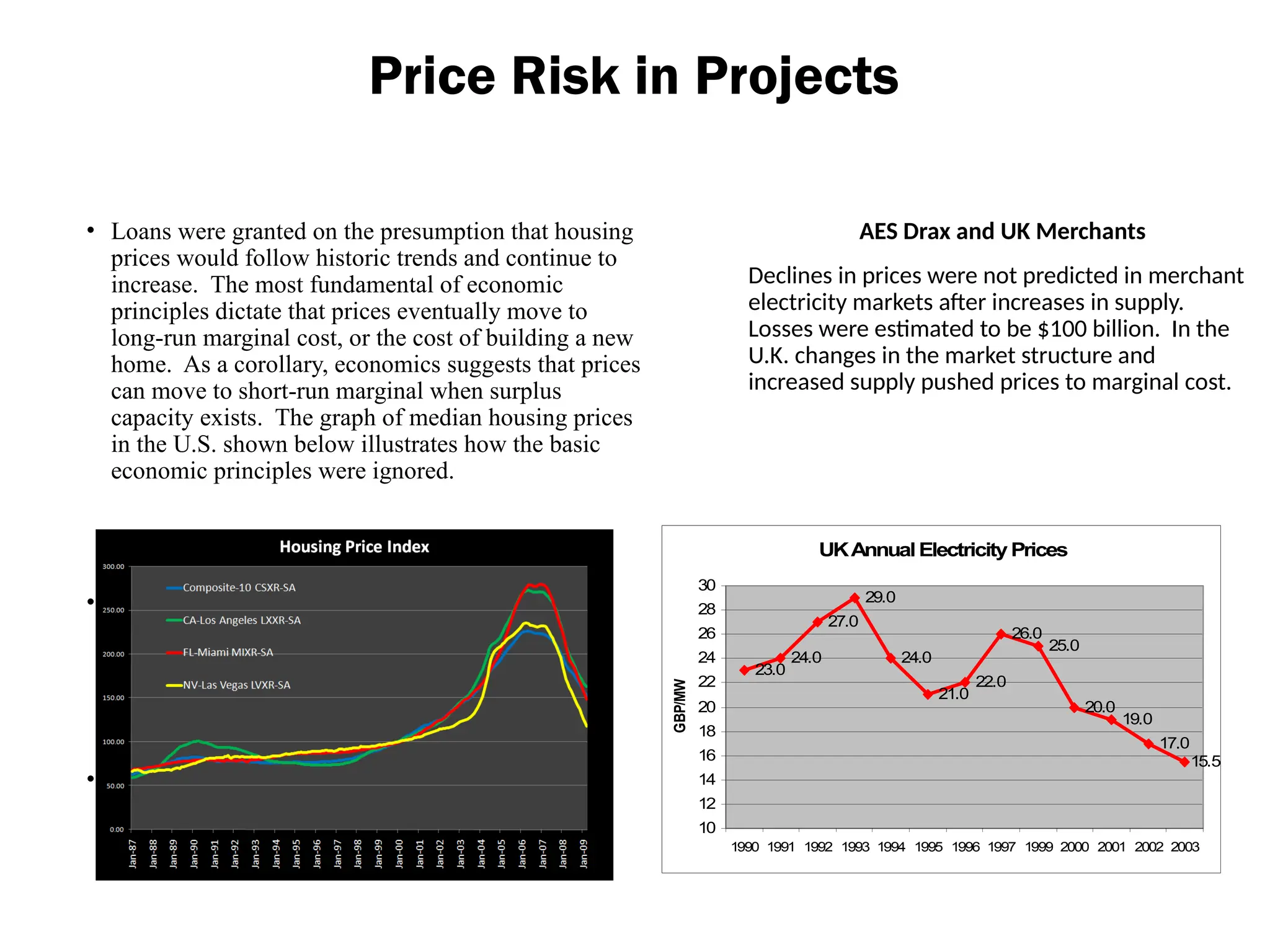

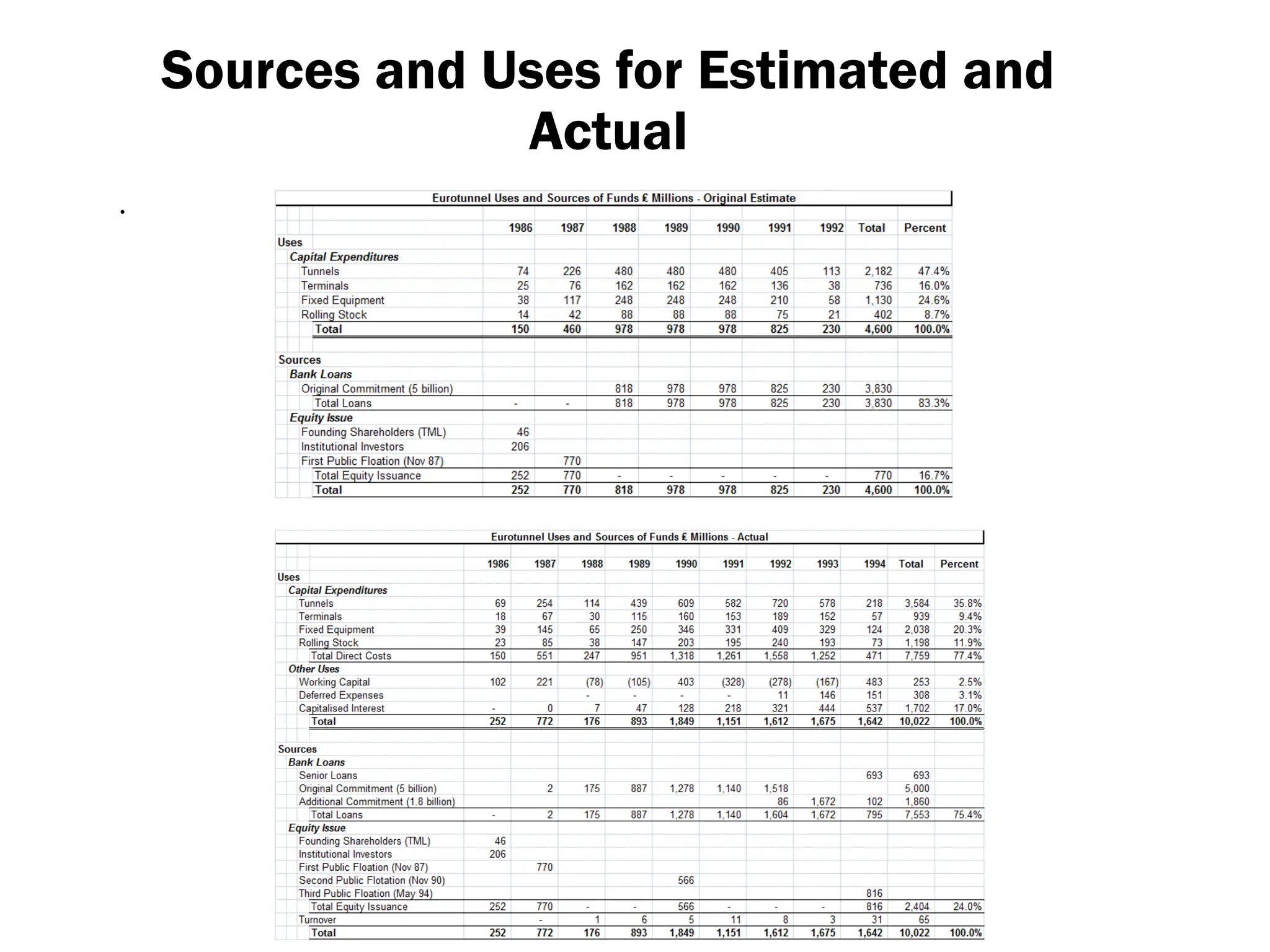

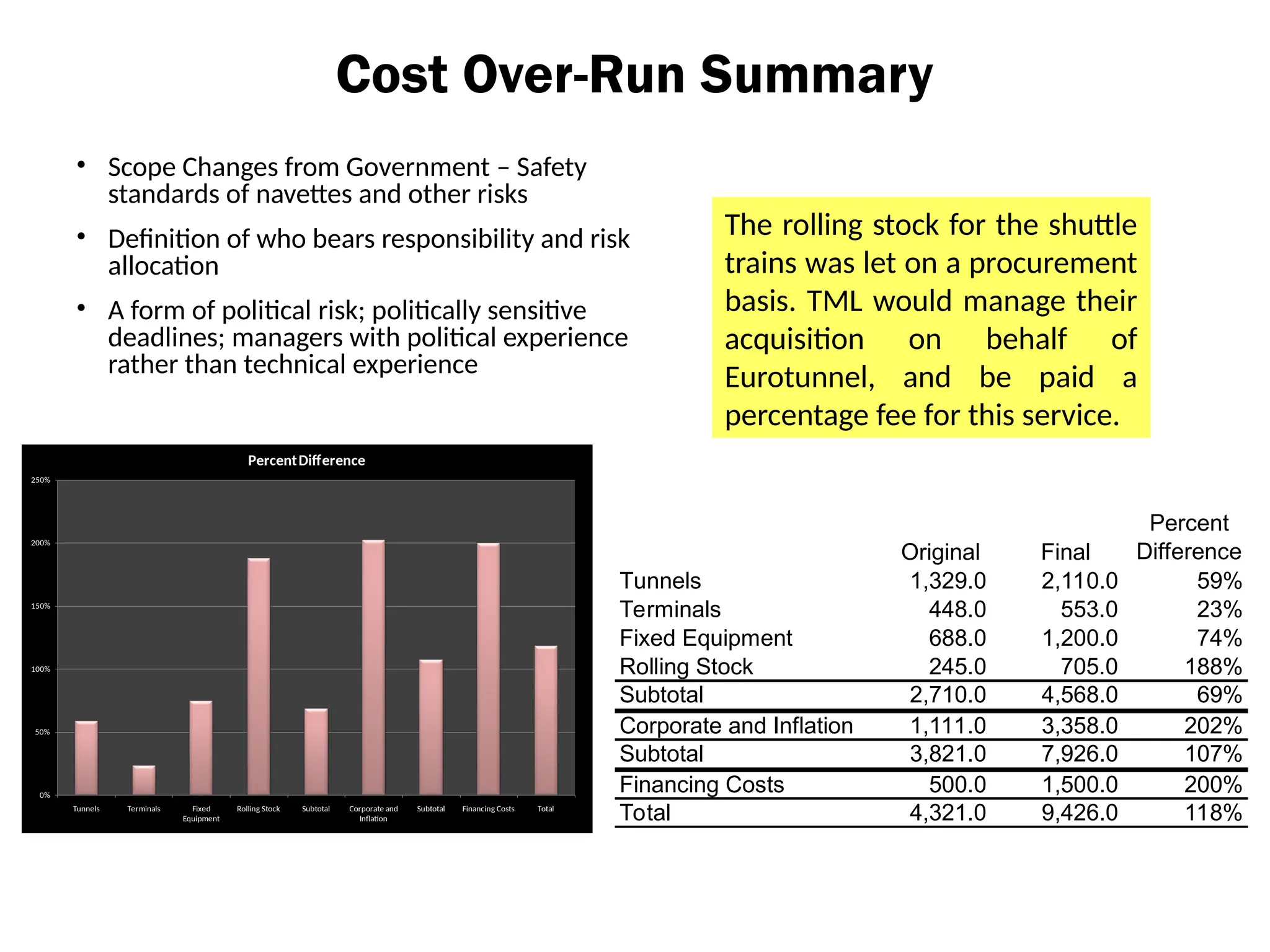

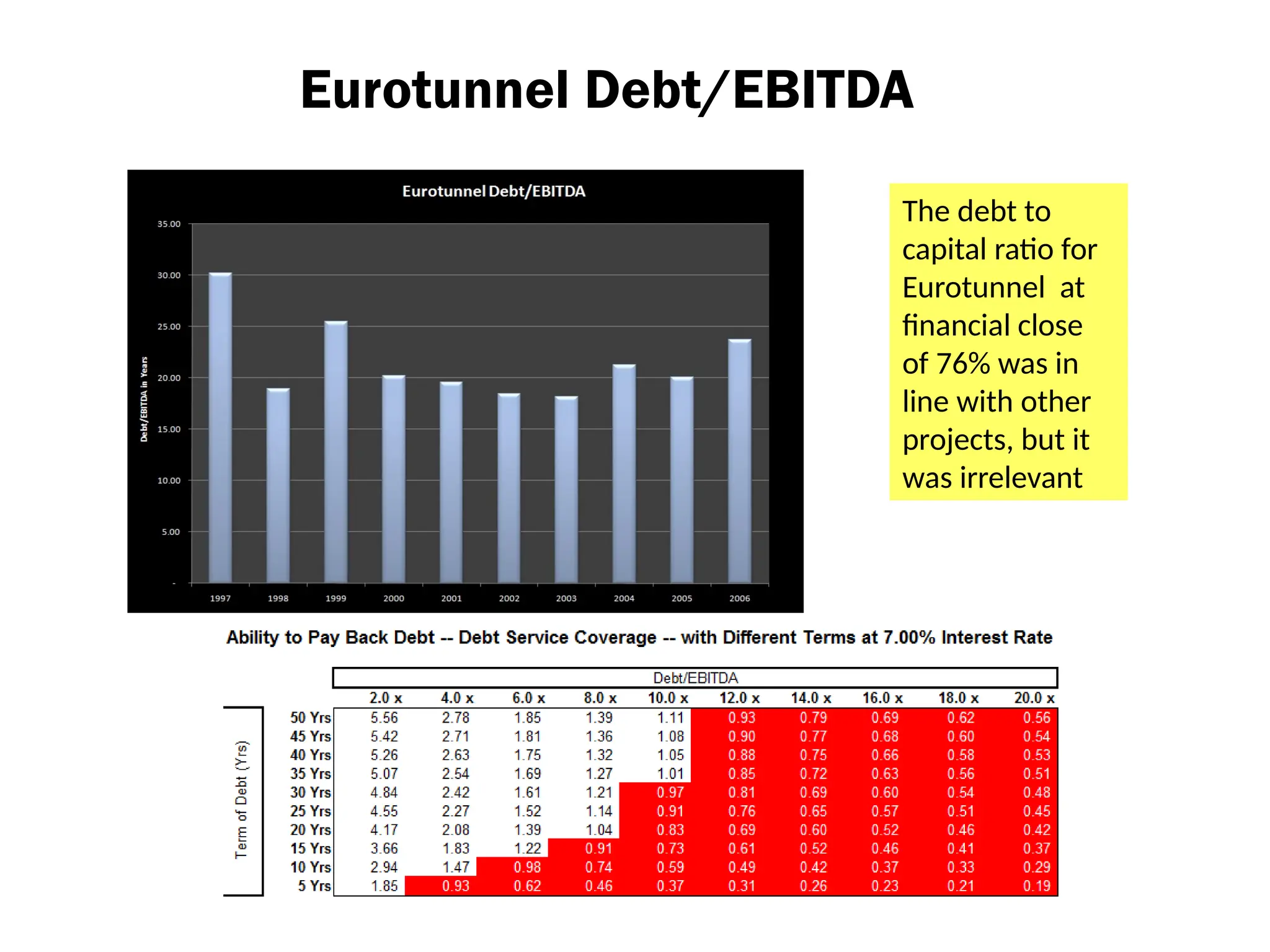

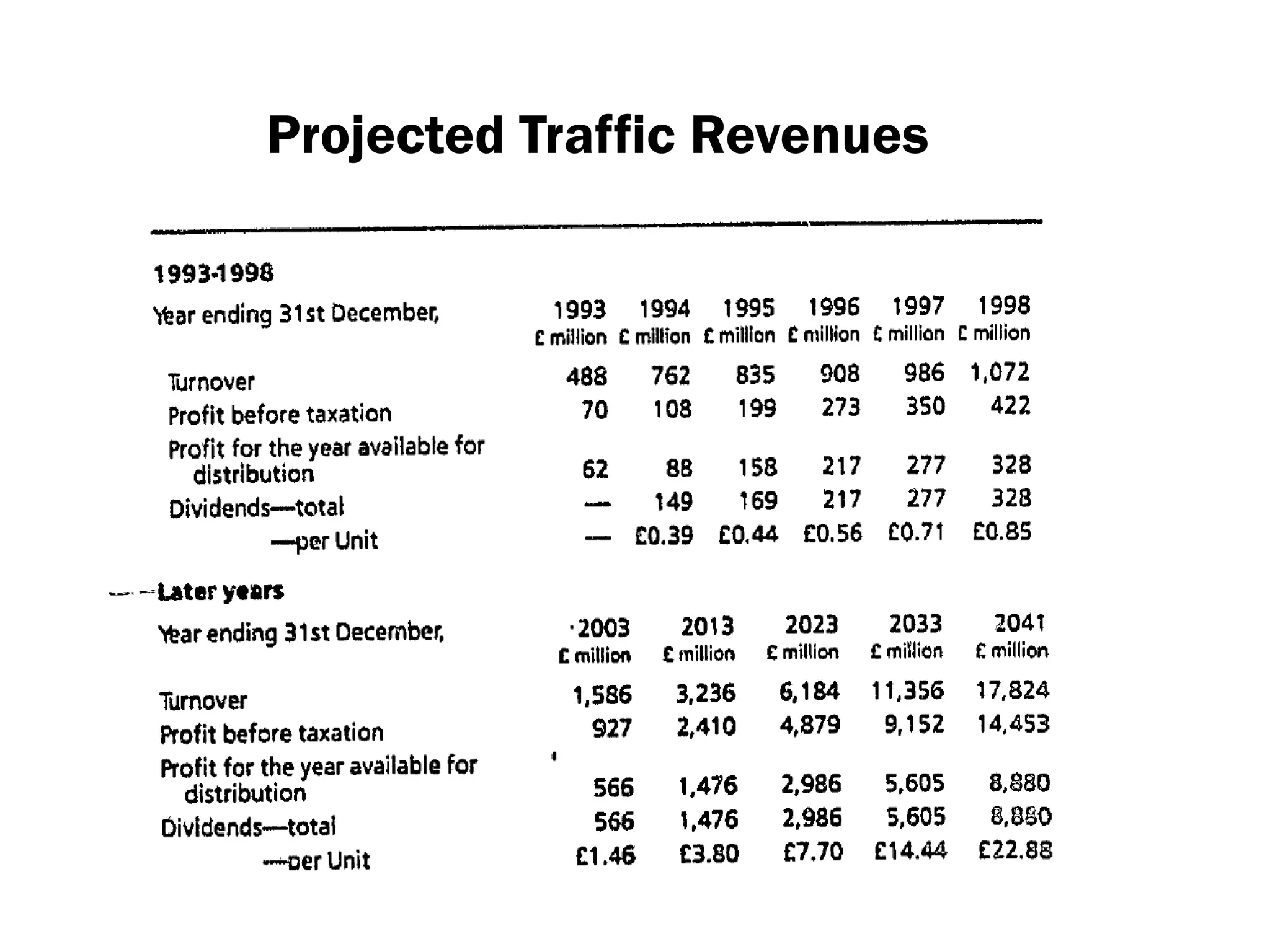

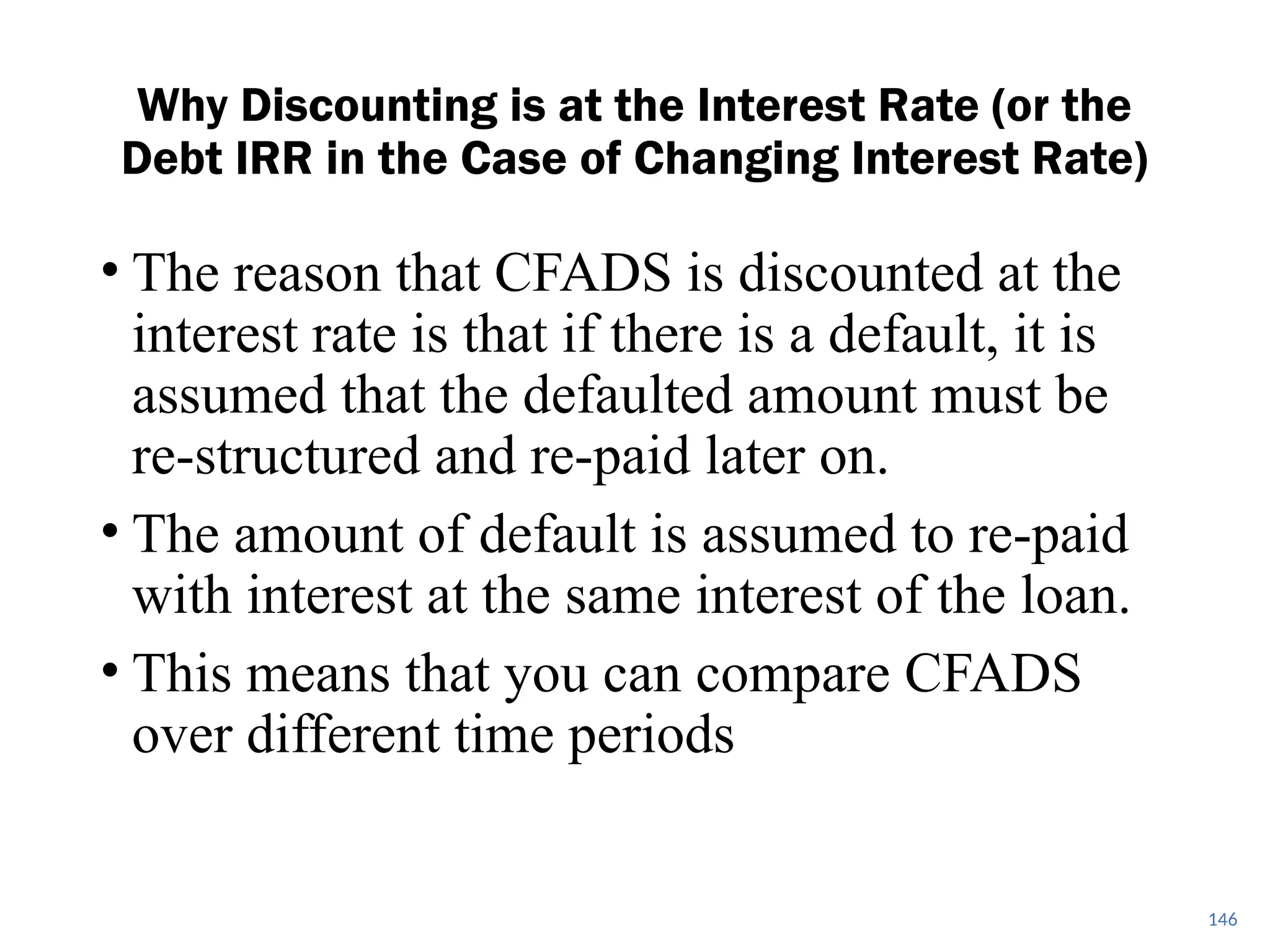

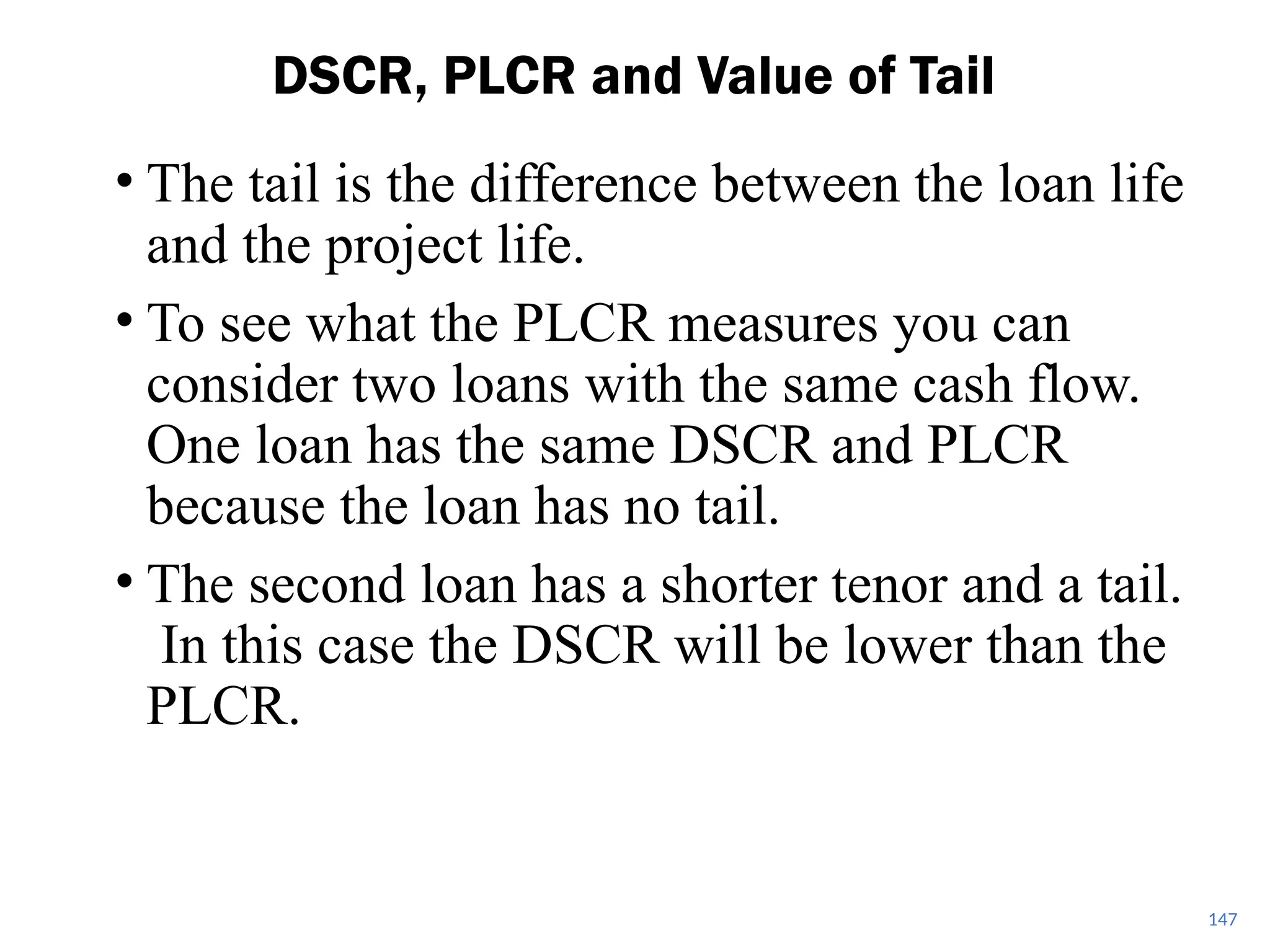

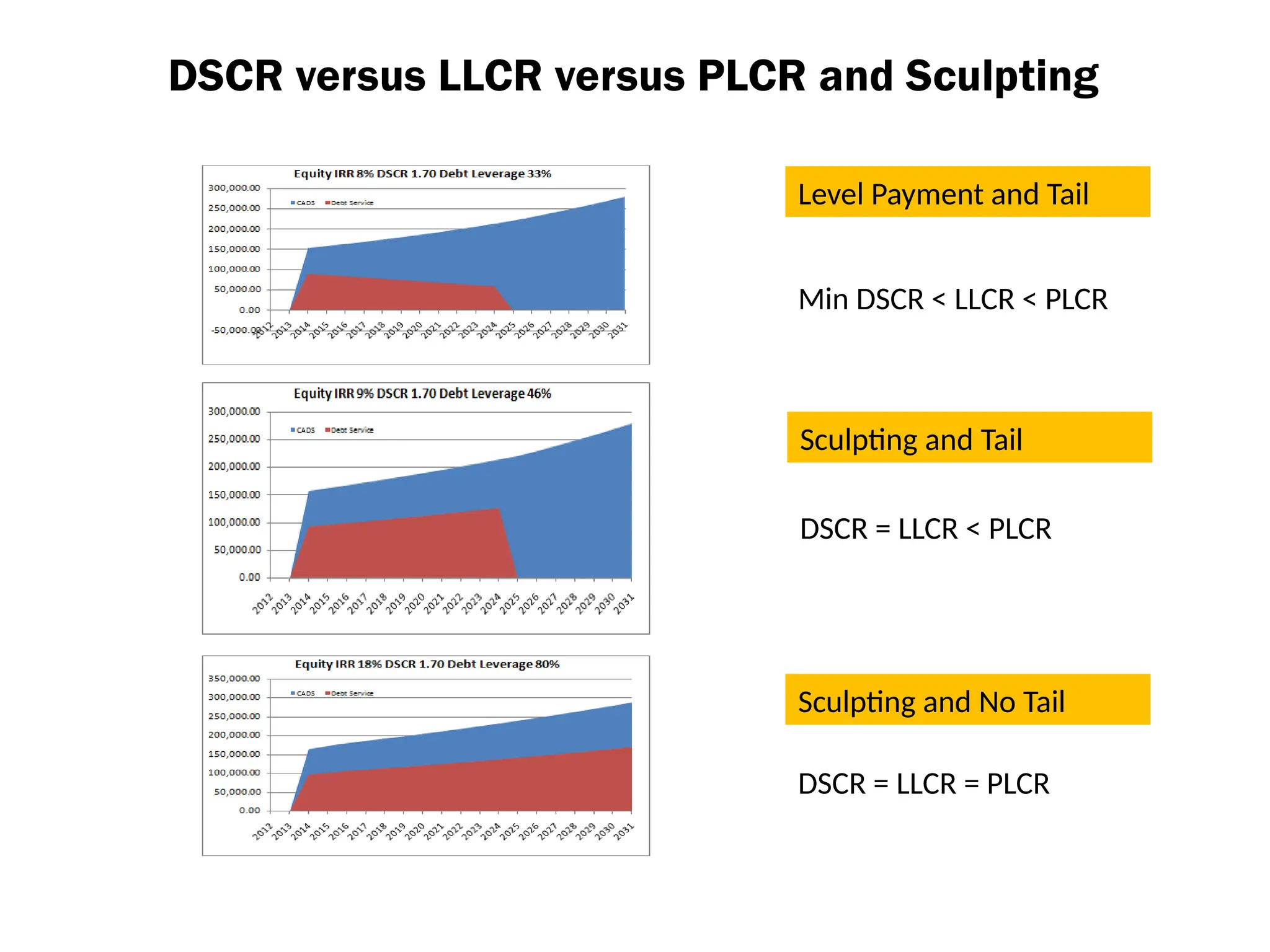

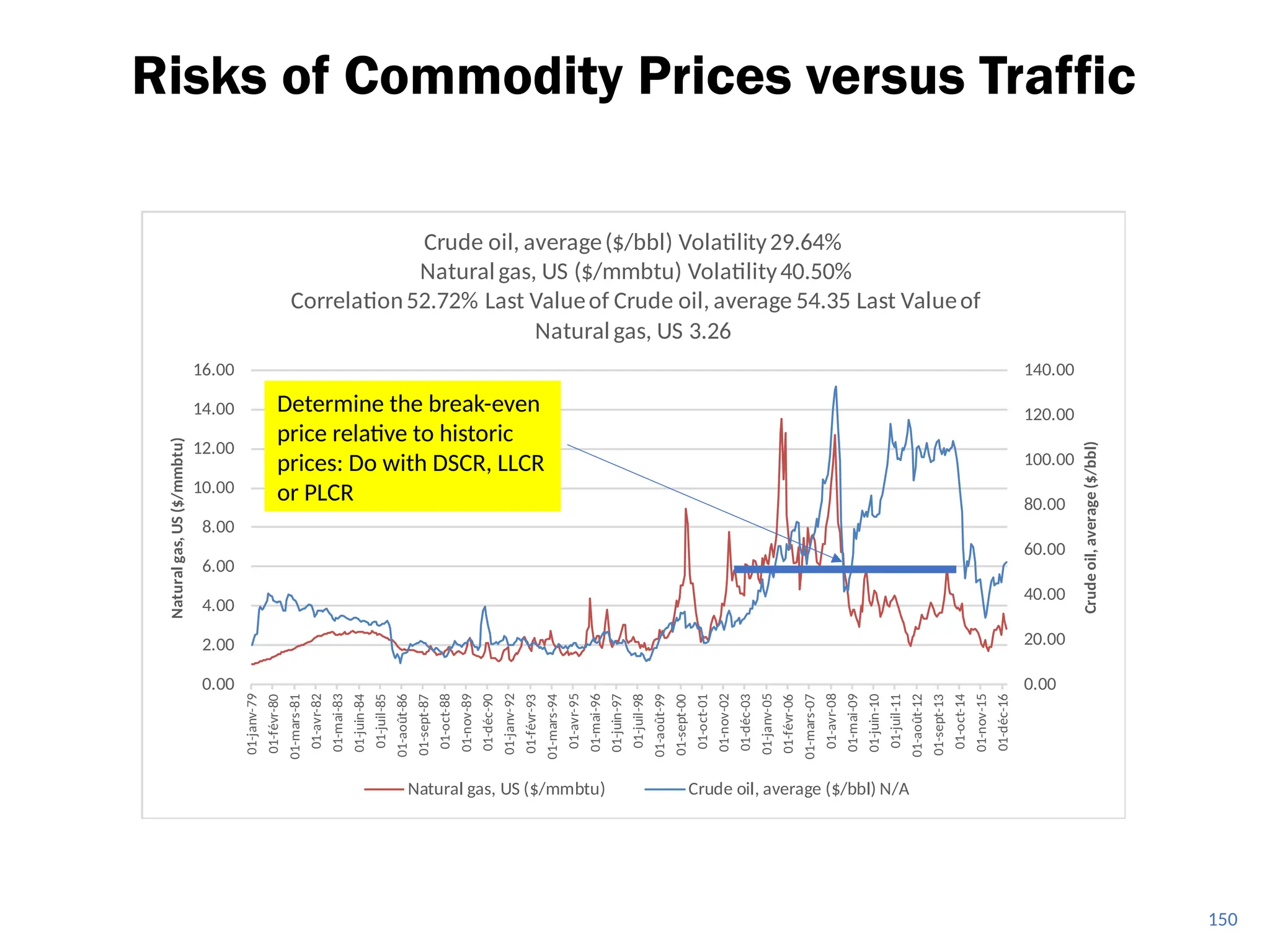

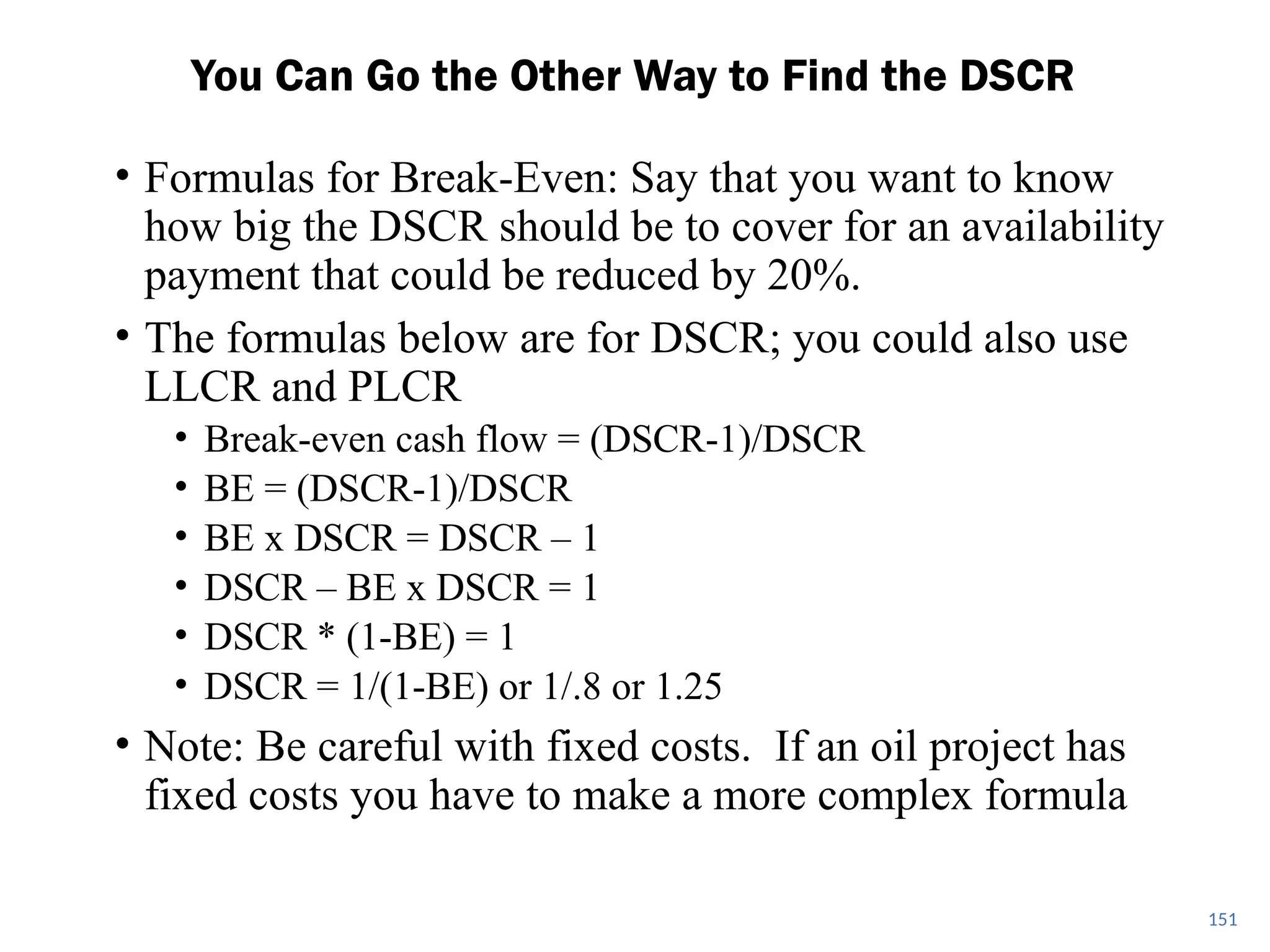

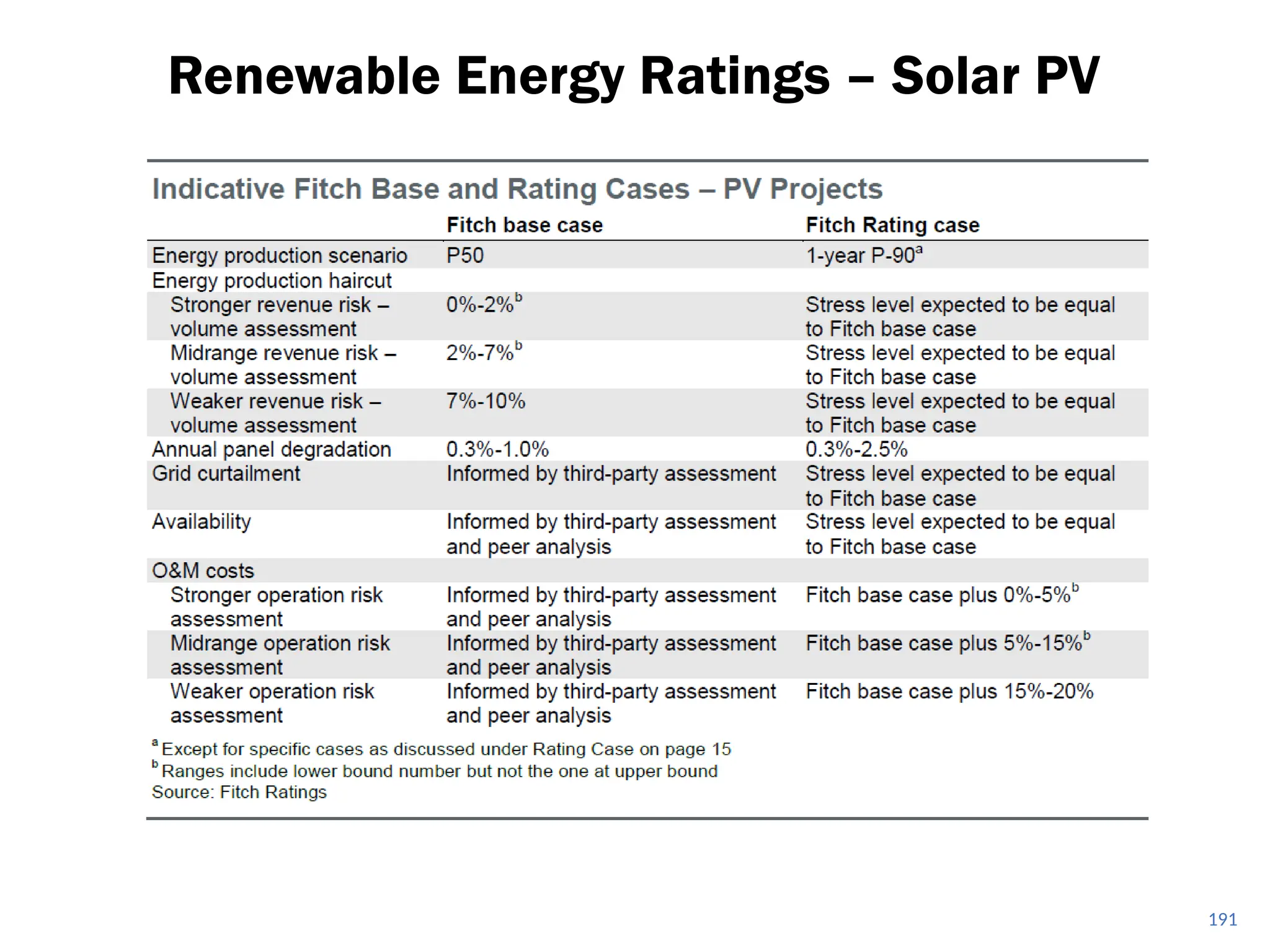

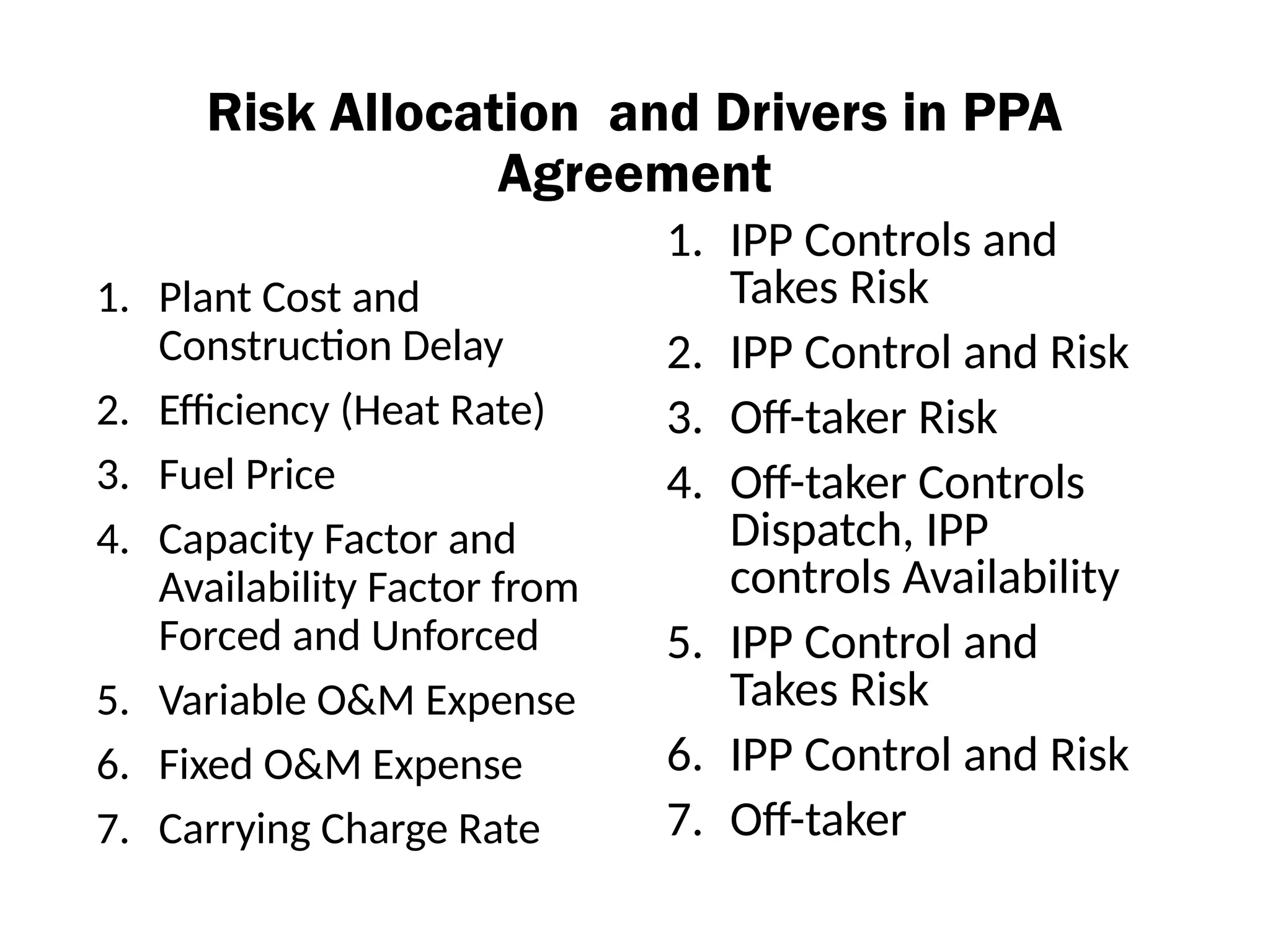

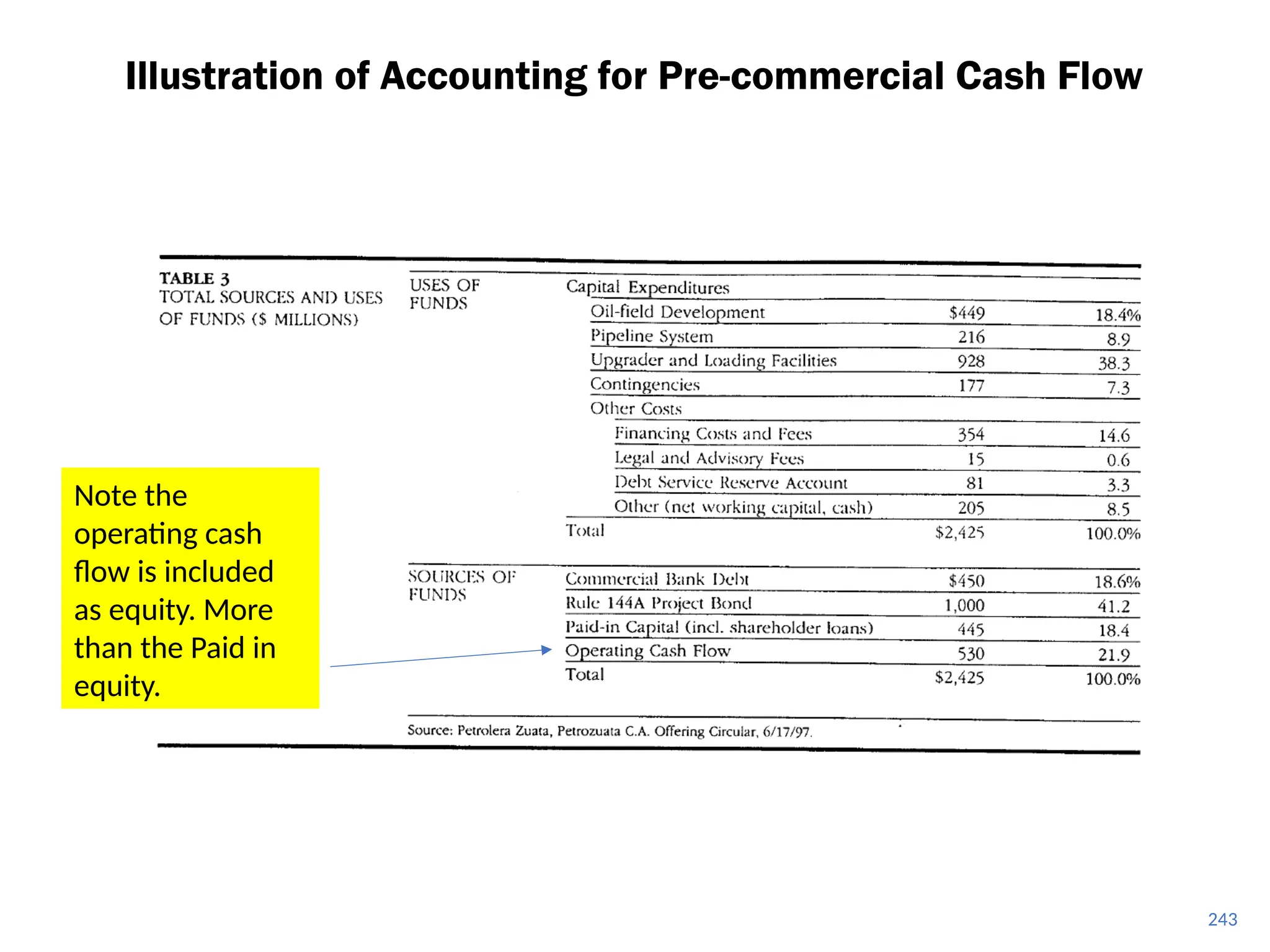

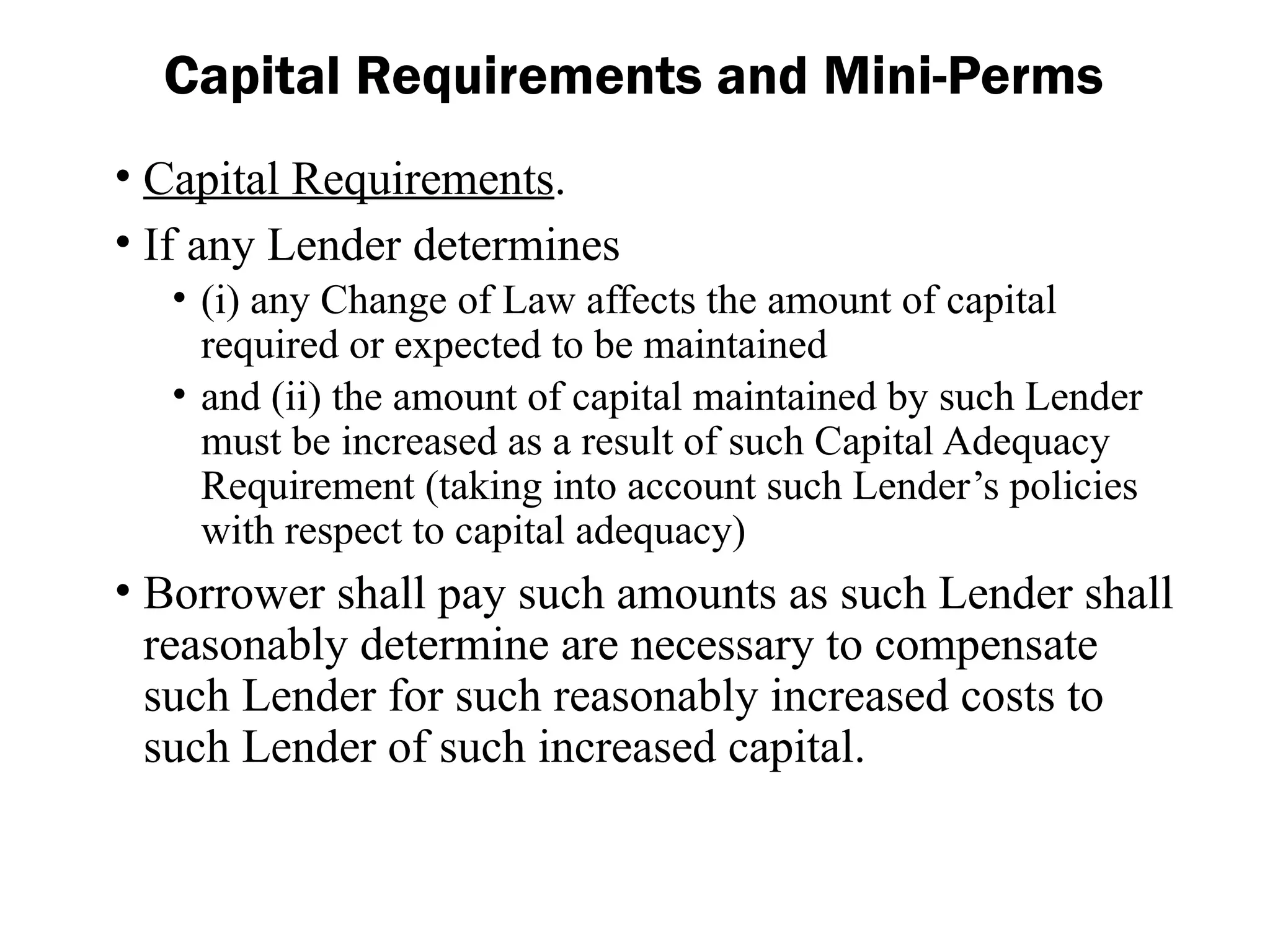

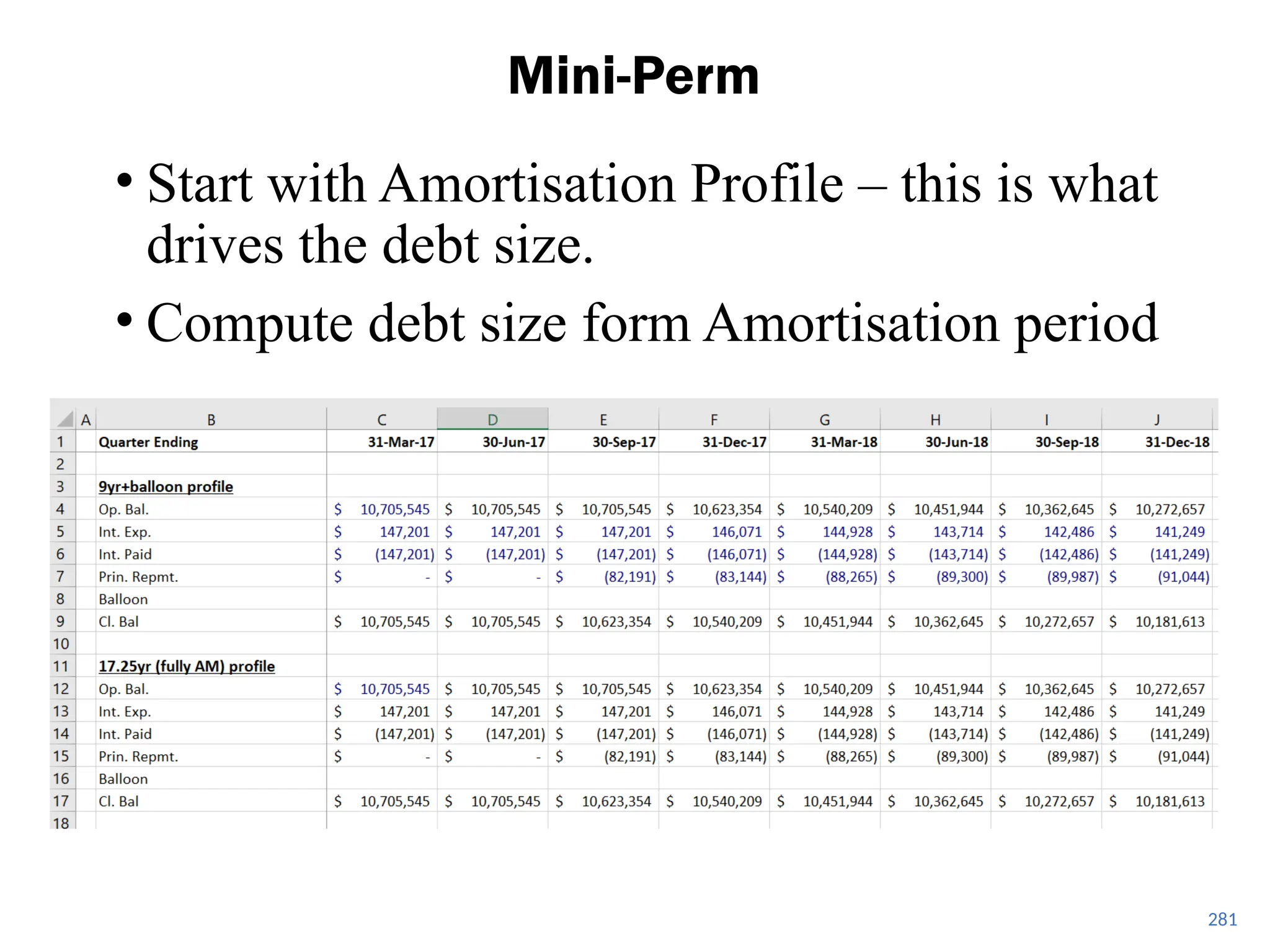

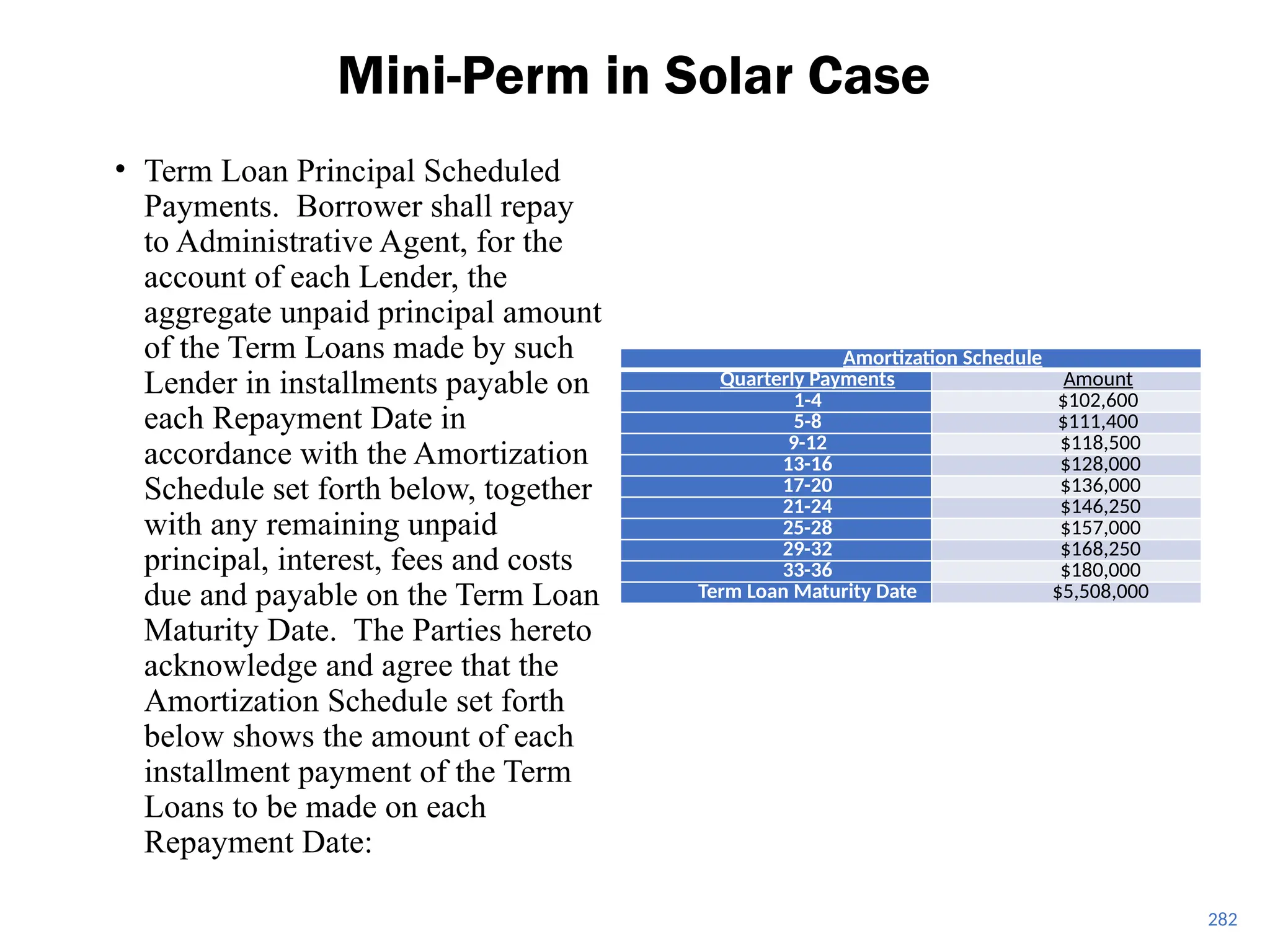

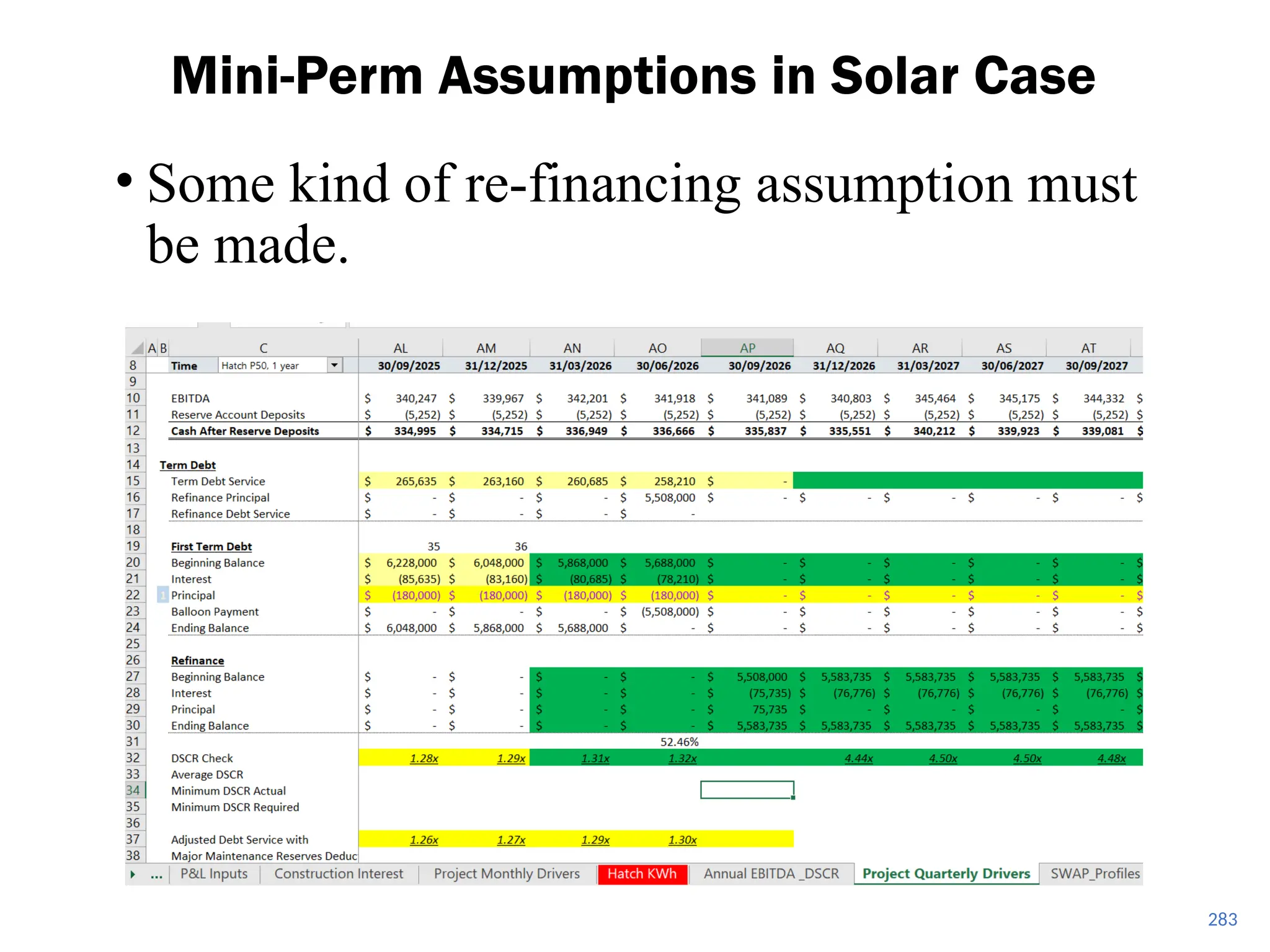

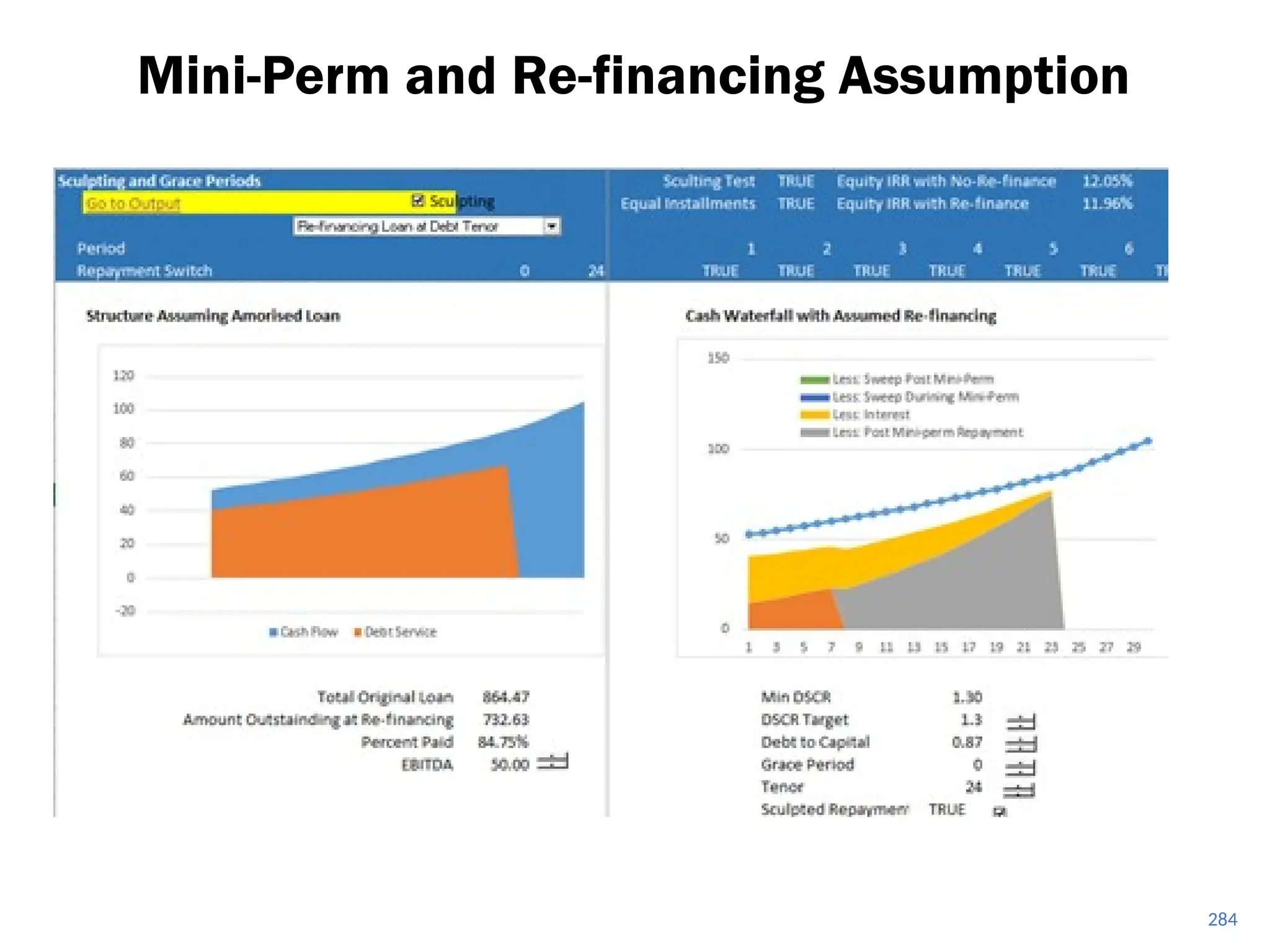

The document compares project finance and corporate finance, highlighting their distinct approaches to valuation and risk assessment, with project finance relying heavily on forecasts and cash flow metrics while corporate finance is grounded in historical company performance. It discusses key financial metrics such as Debt Service Coverage Ratio (DSCR), equity Internal Rate of Return (IRR), and other valuation ratios, emphasizing the importance of these measures in project finance for determining debt sizing and repayment structures. Additional sections detail the contractual nuances in project finance, variations in risk assessment across industries, and the interplay of different financial ratios in assessing credit risk.

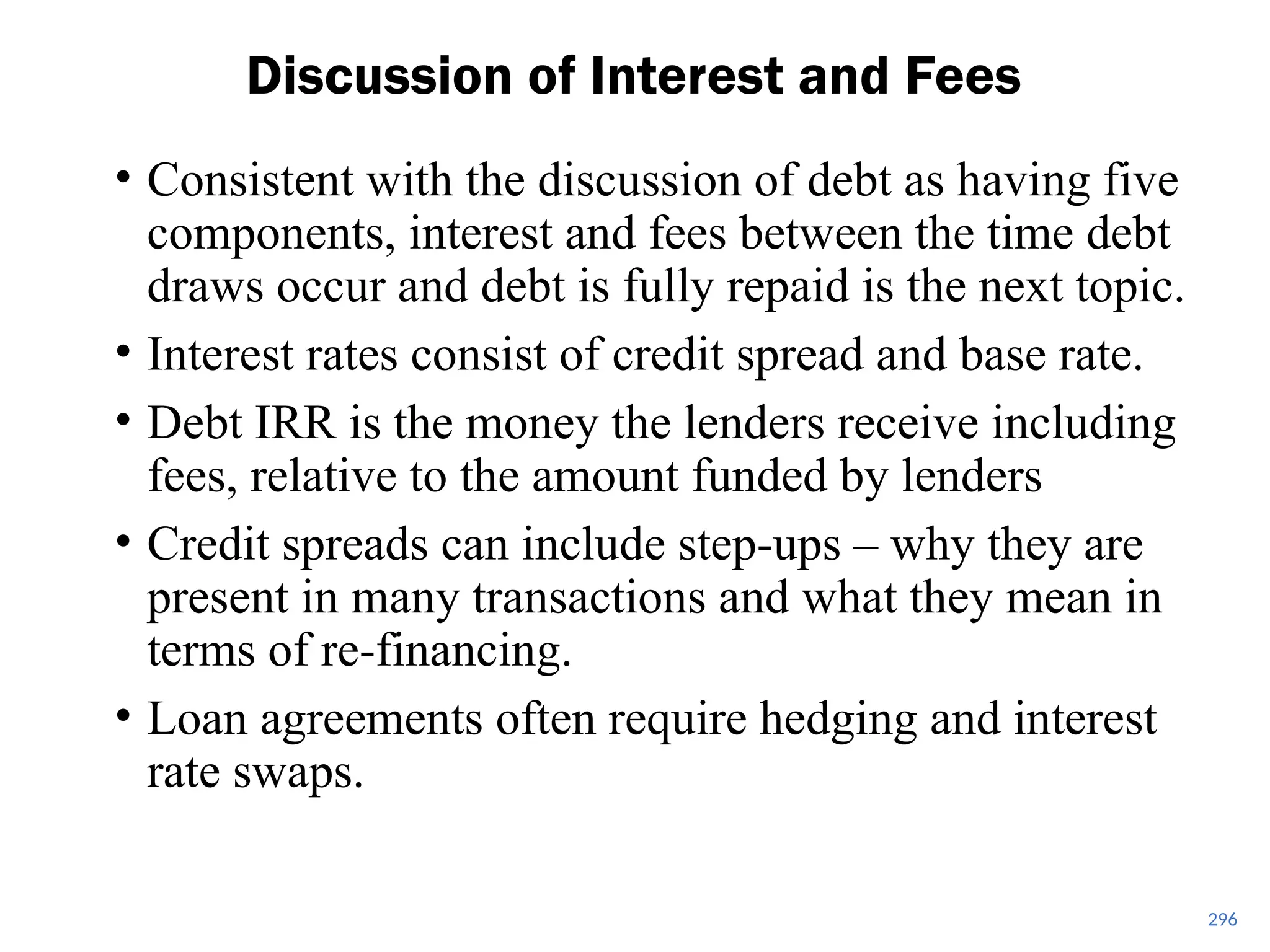

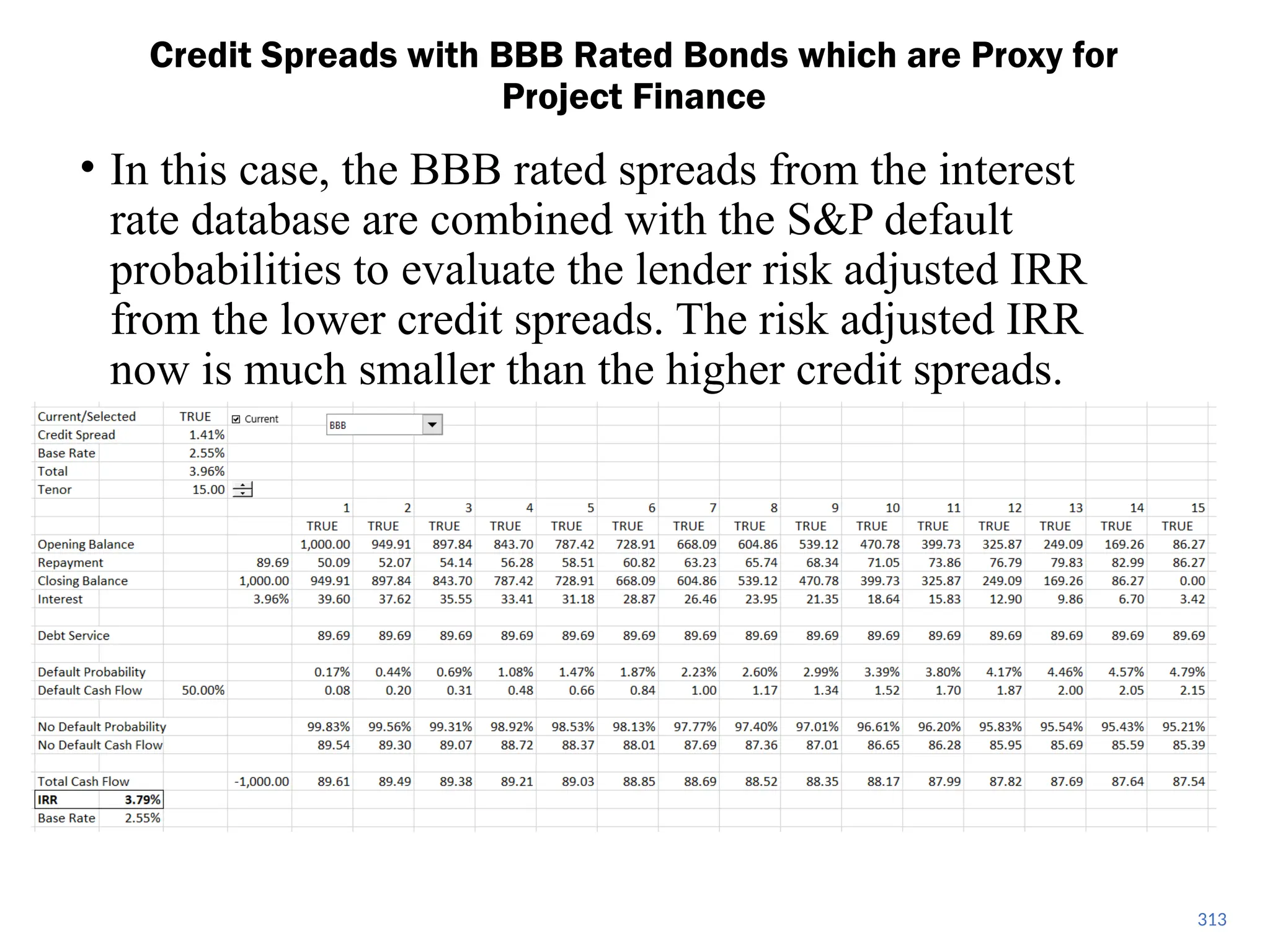

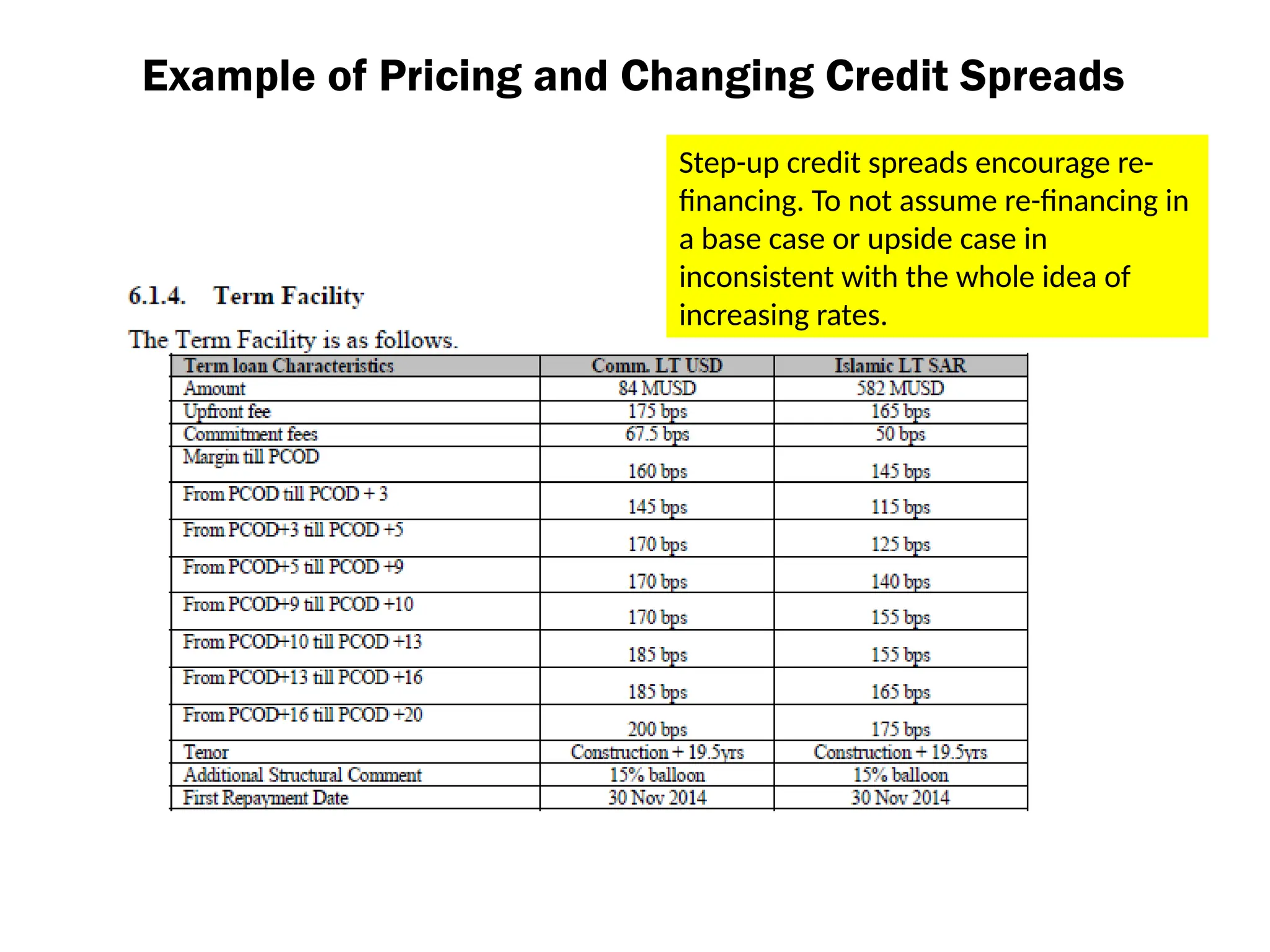

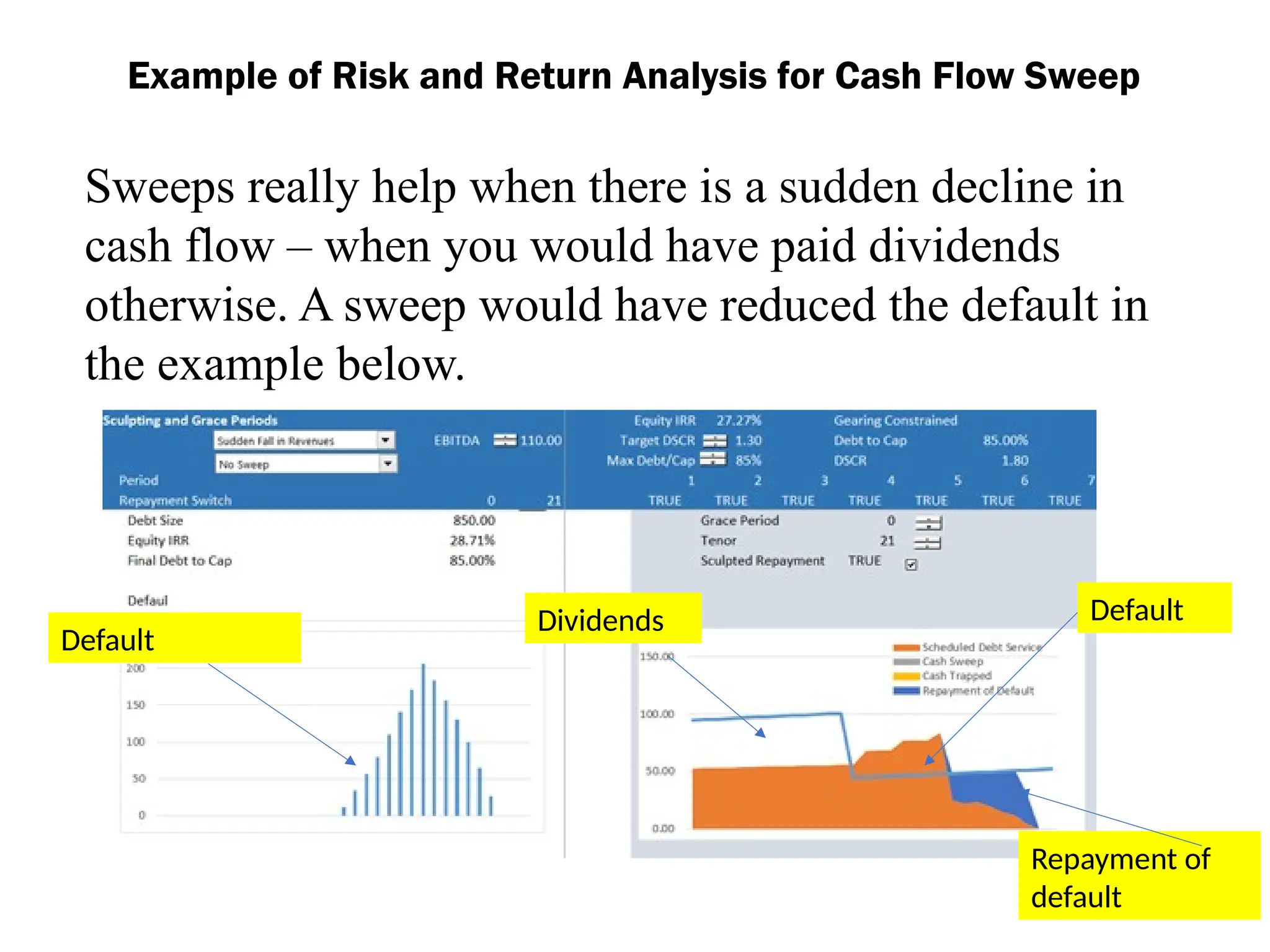

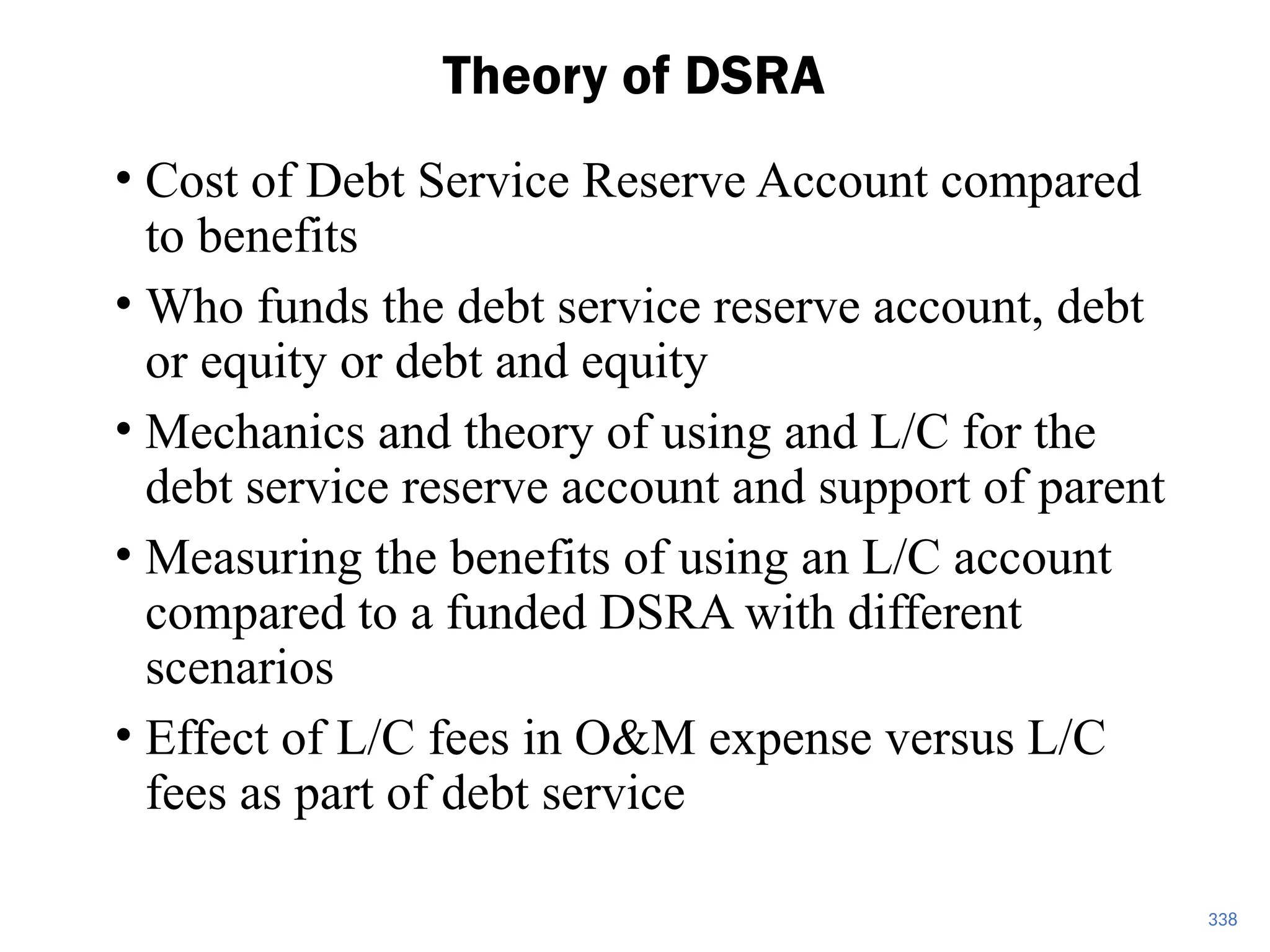

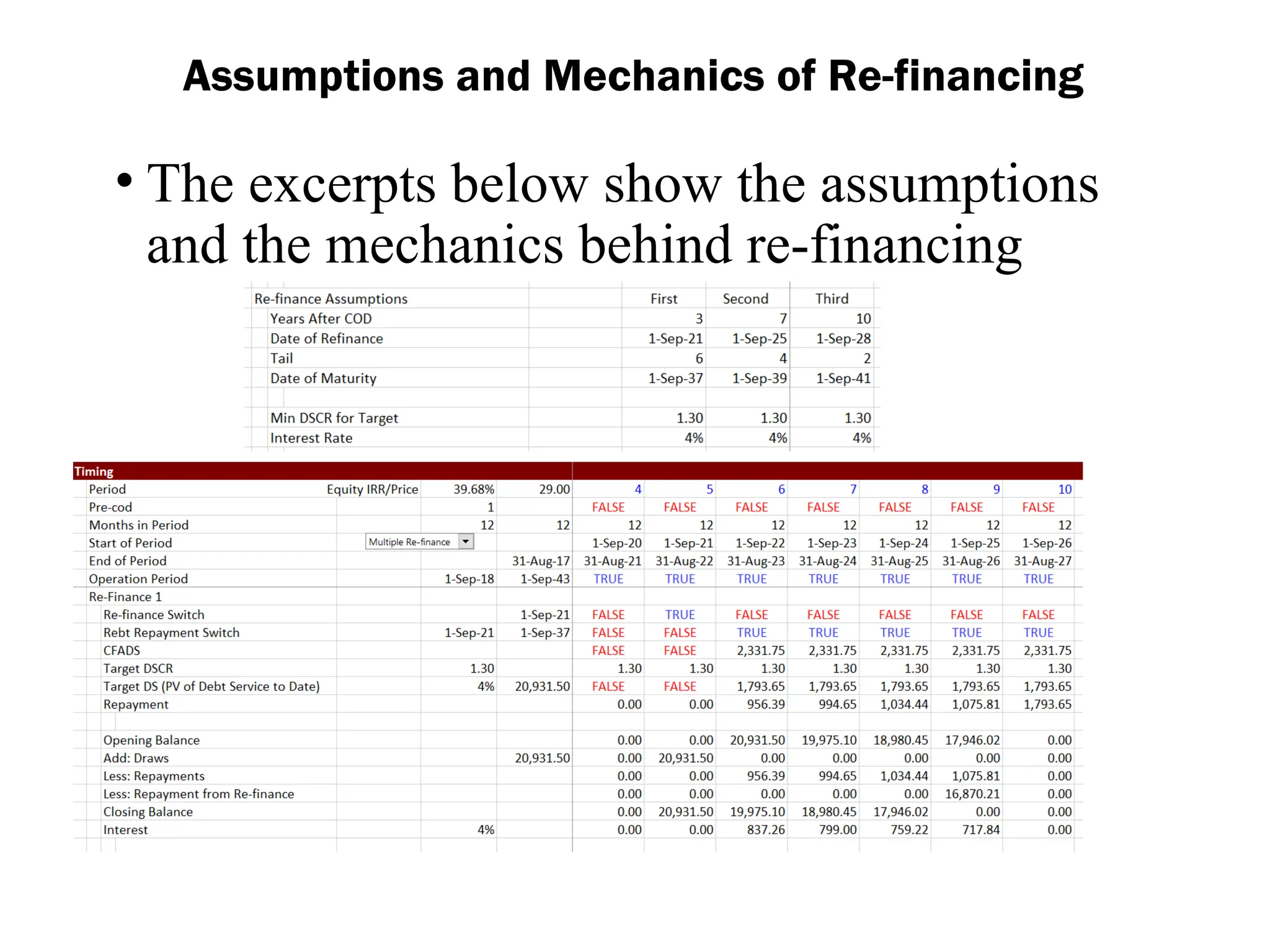

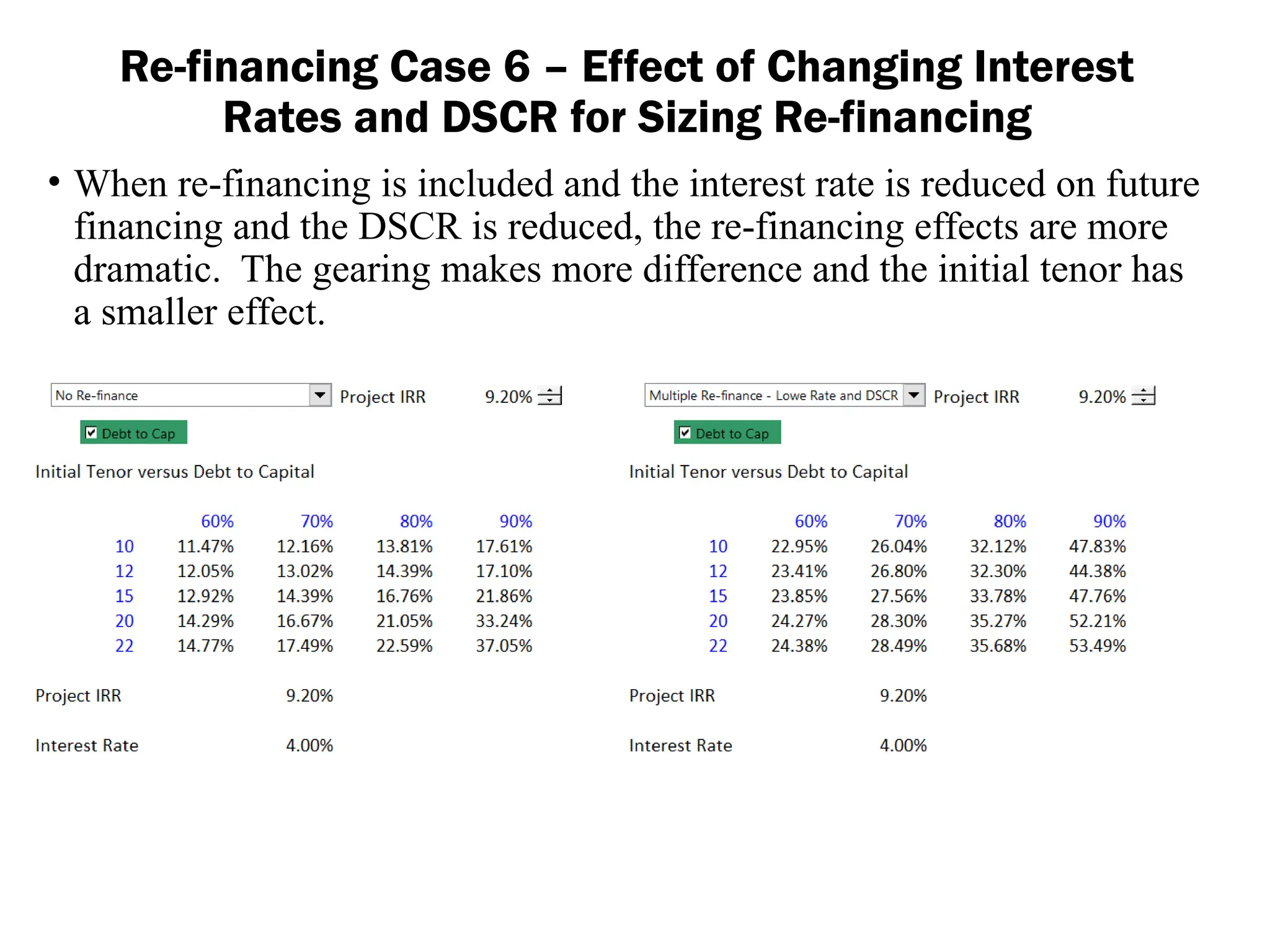

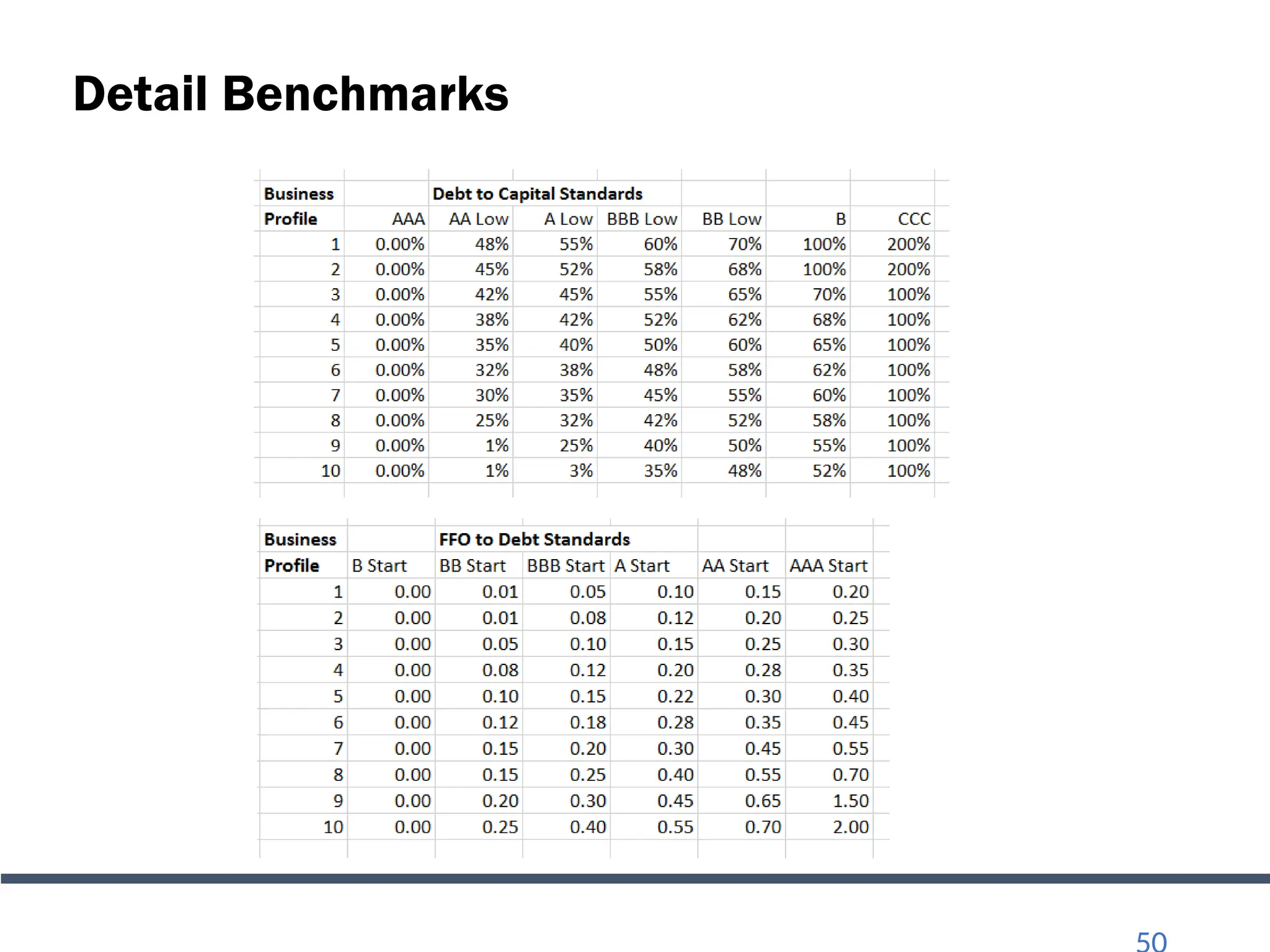

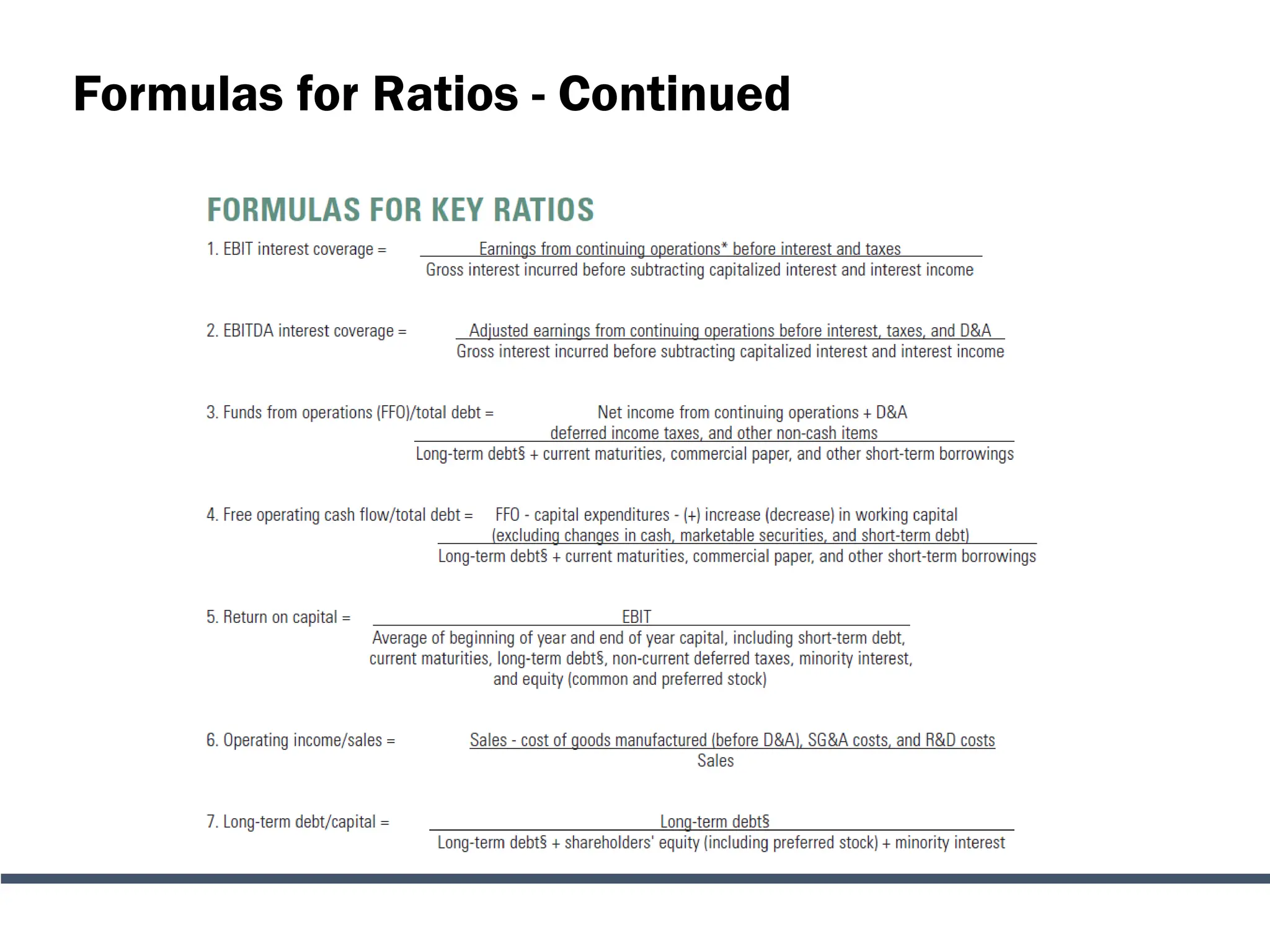

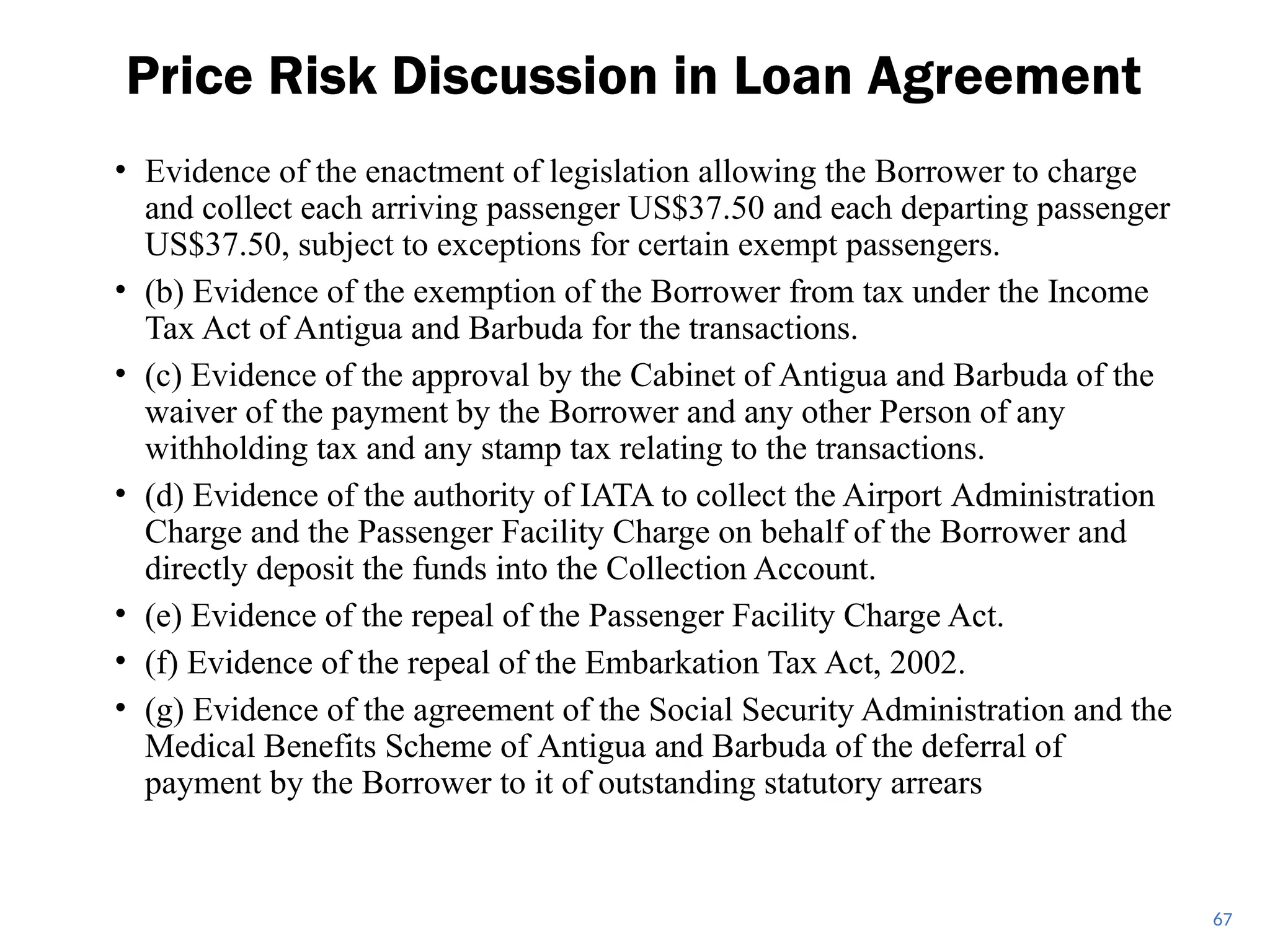

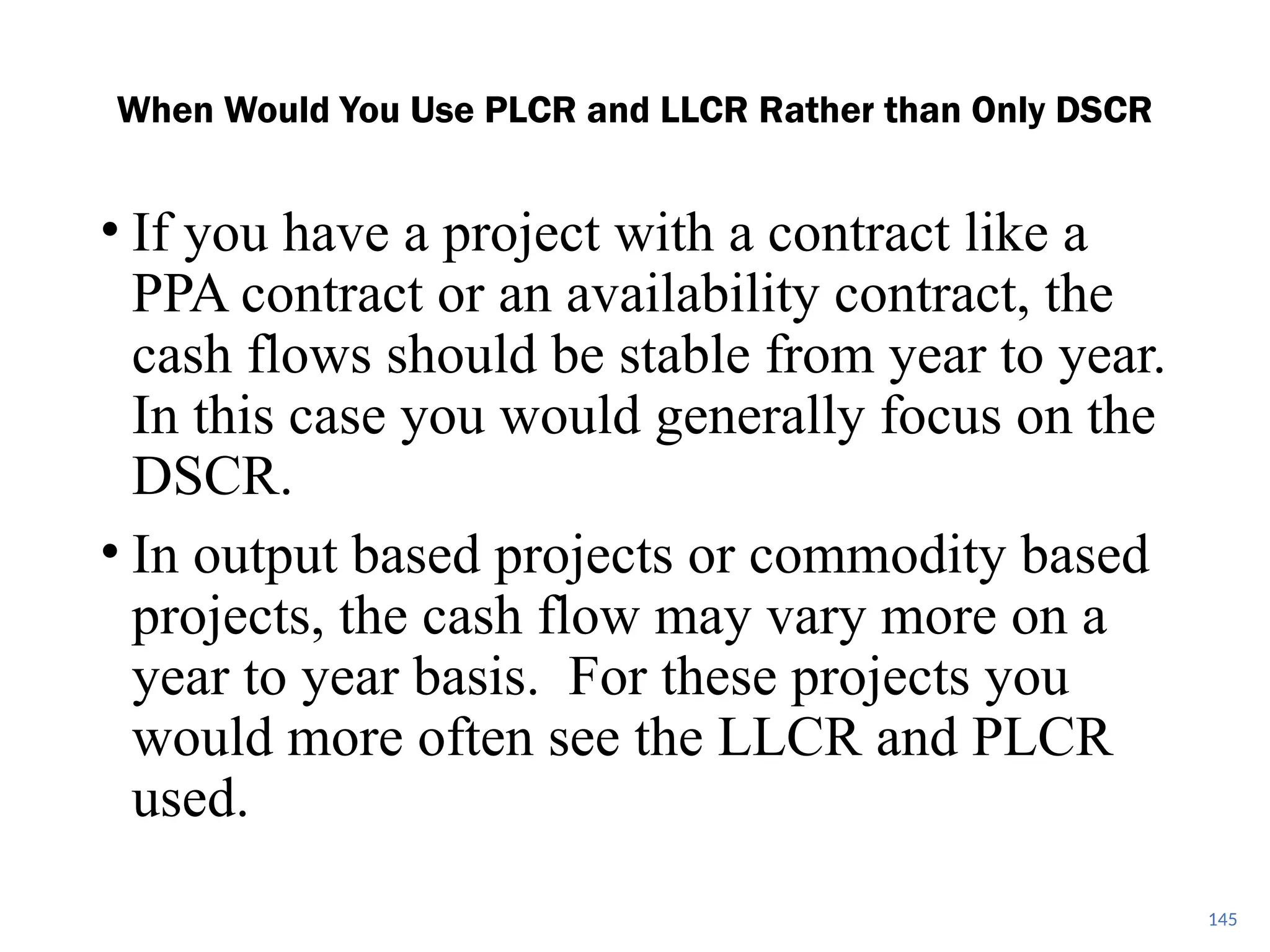

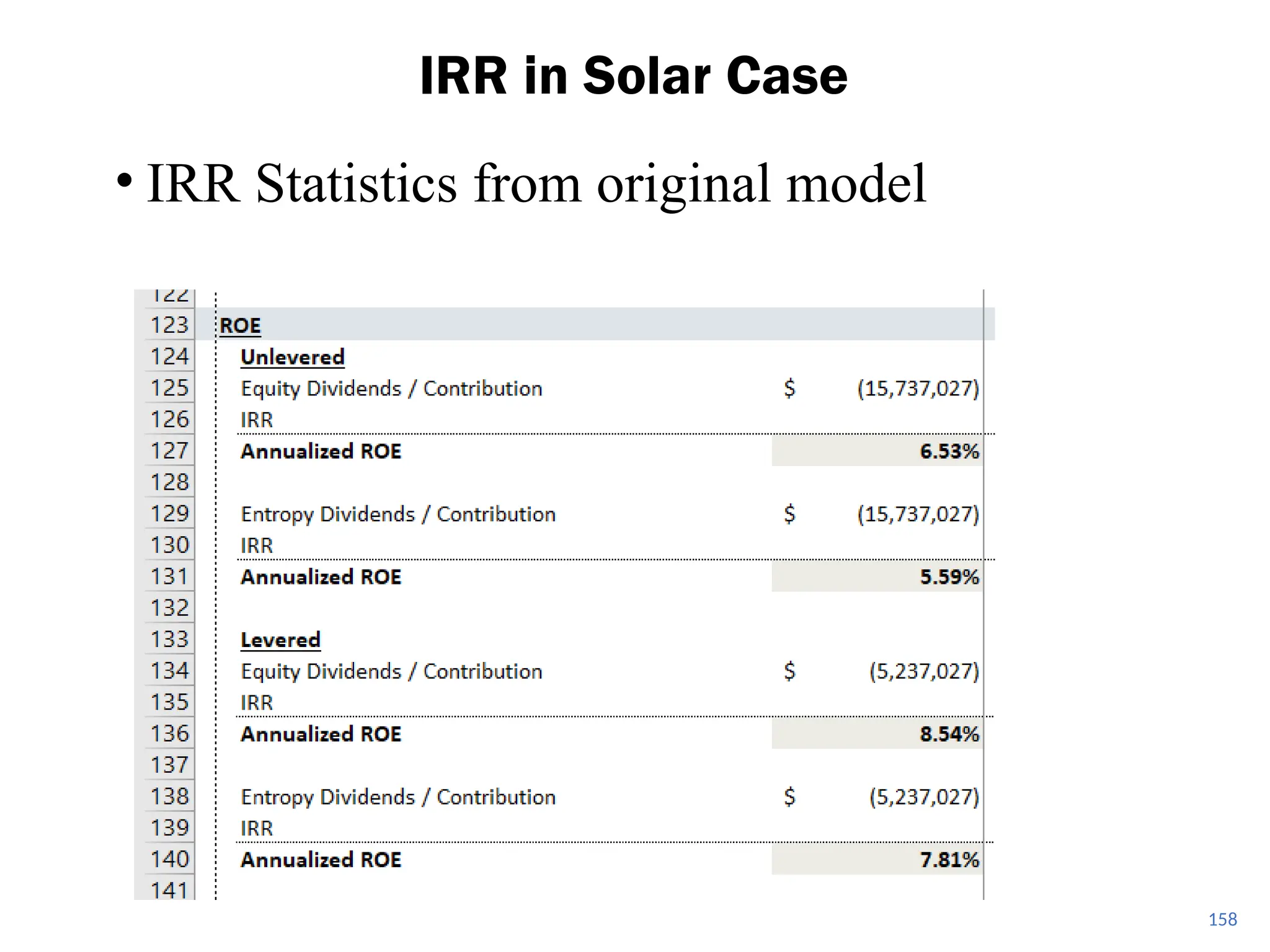

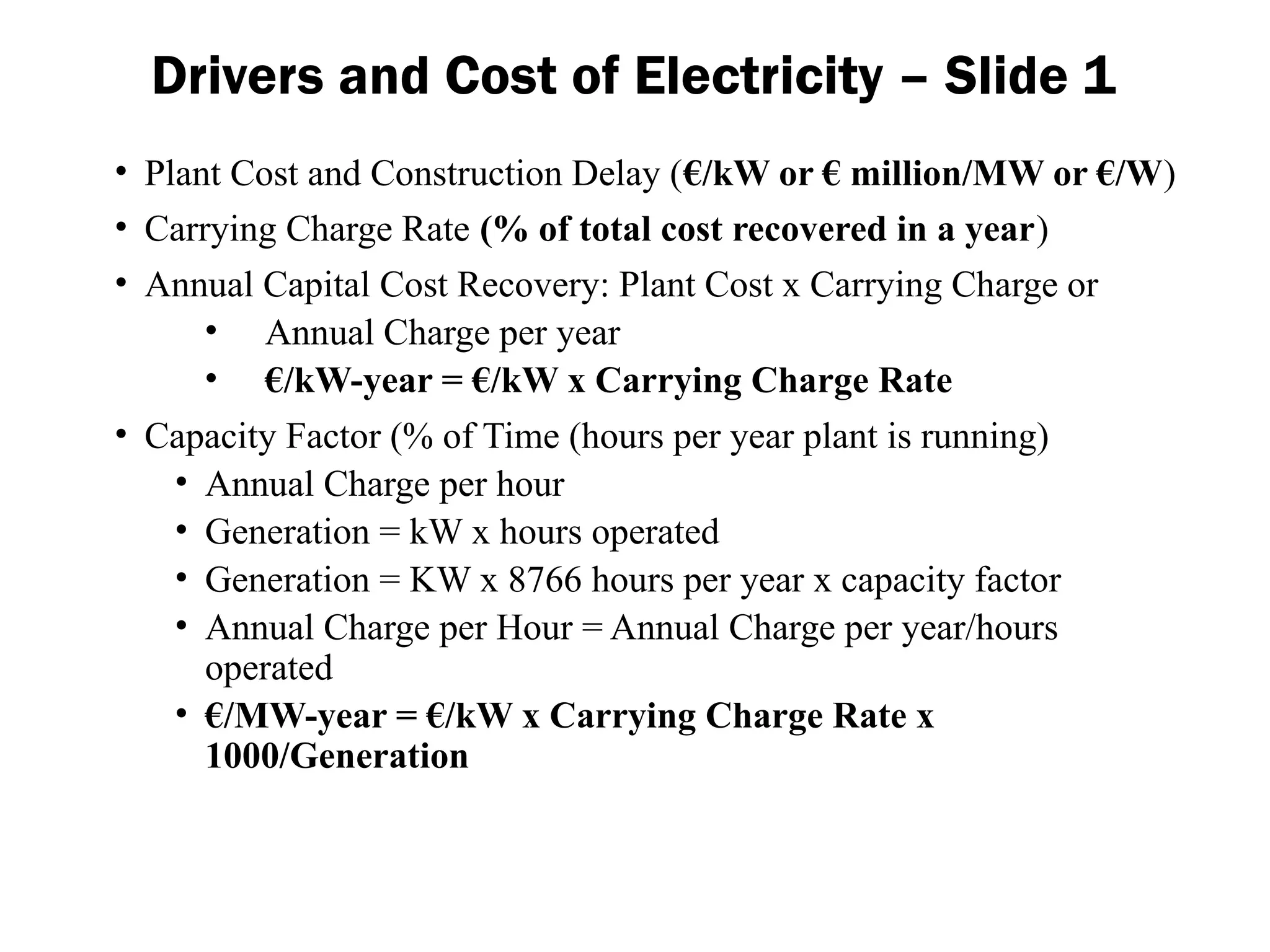

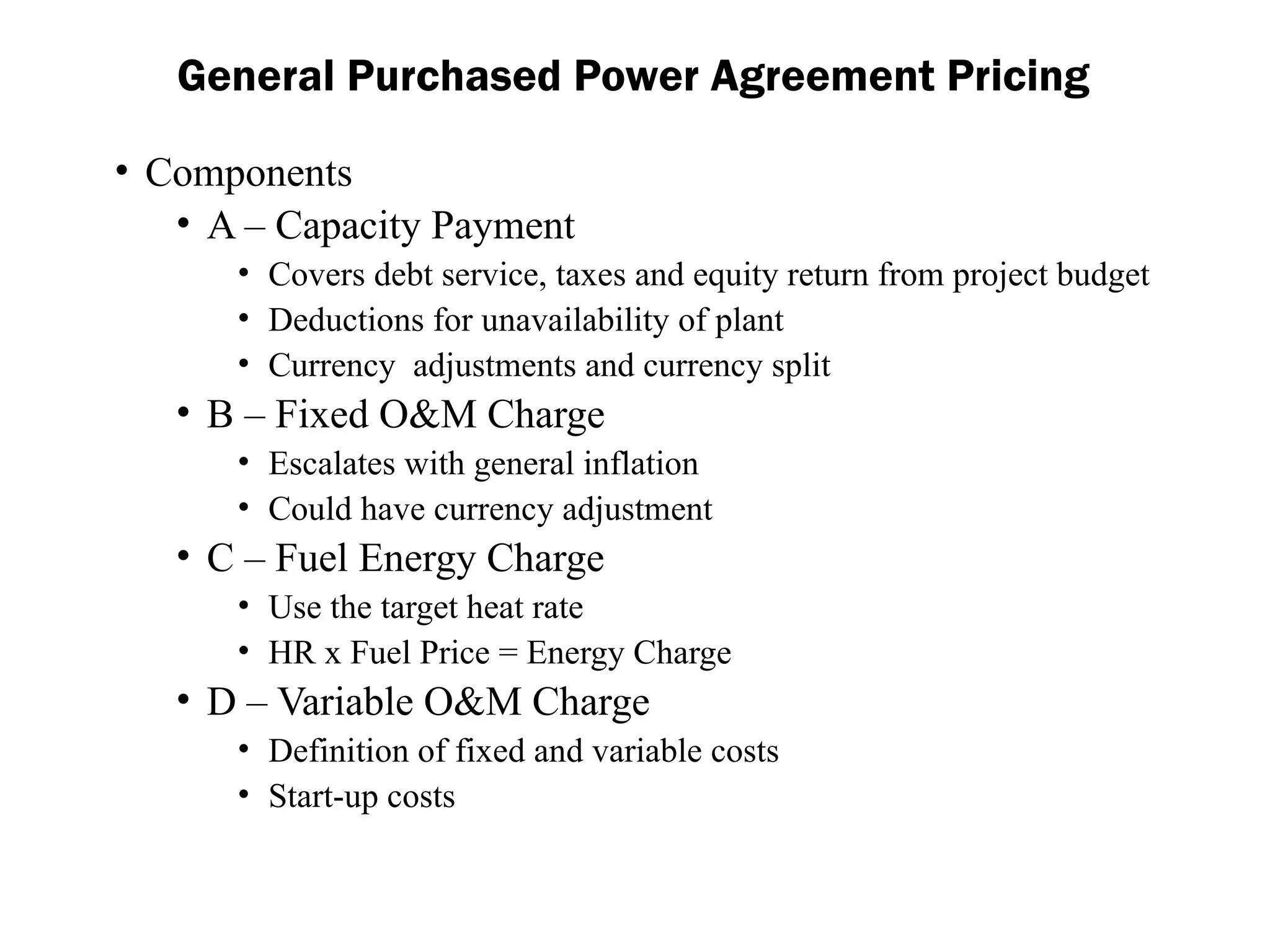

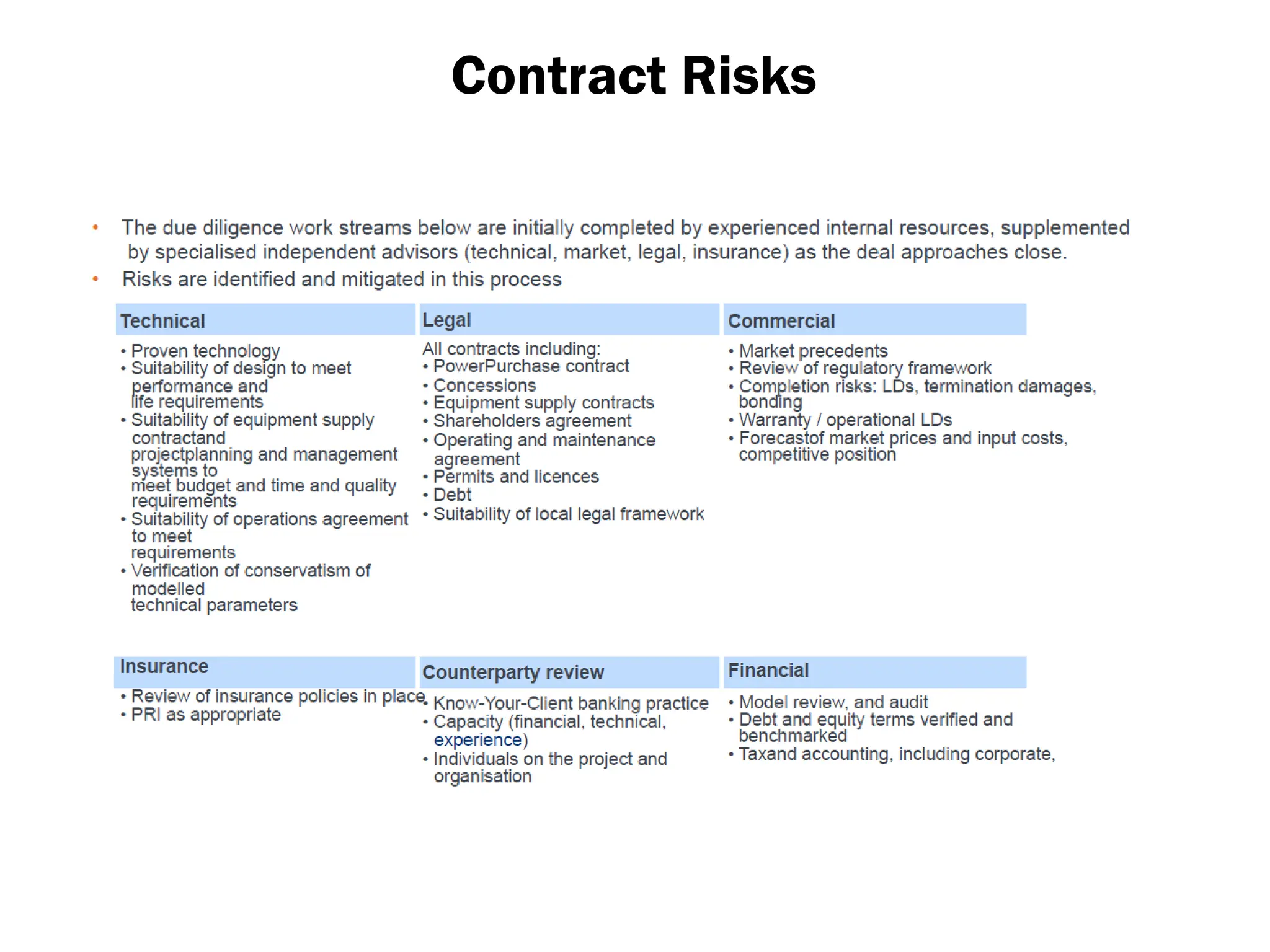

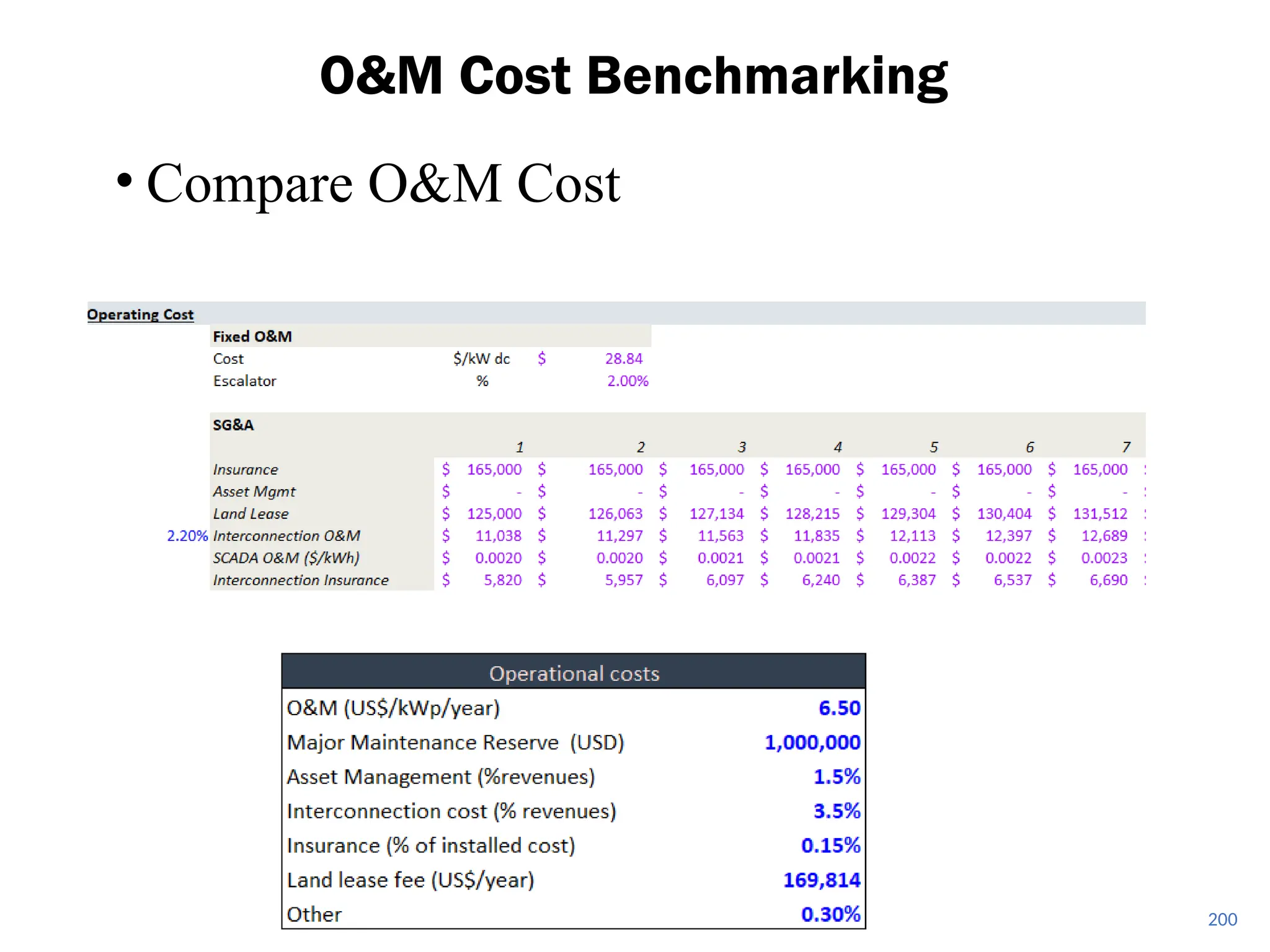

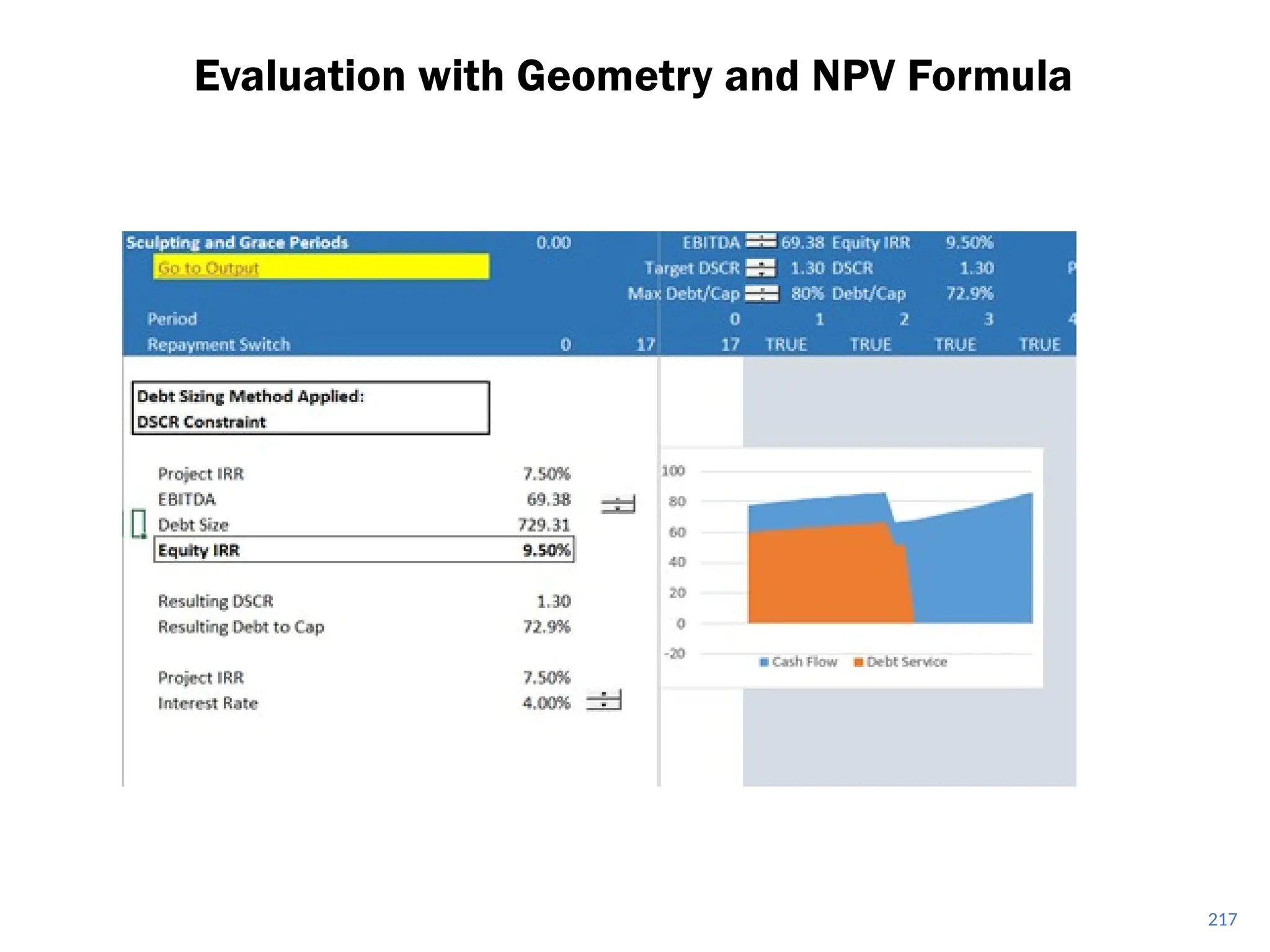

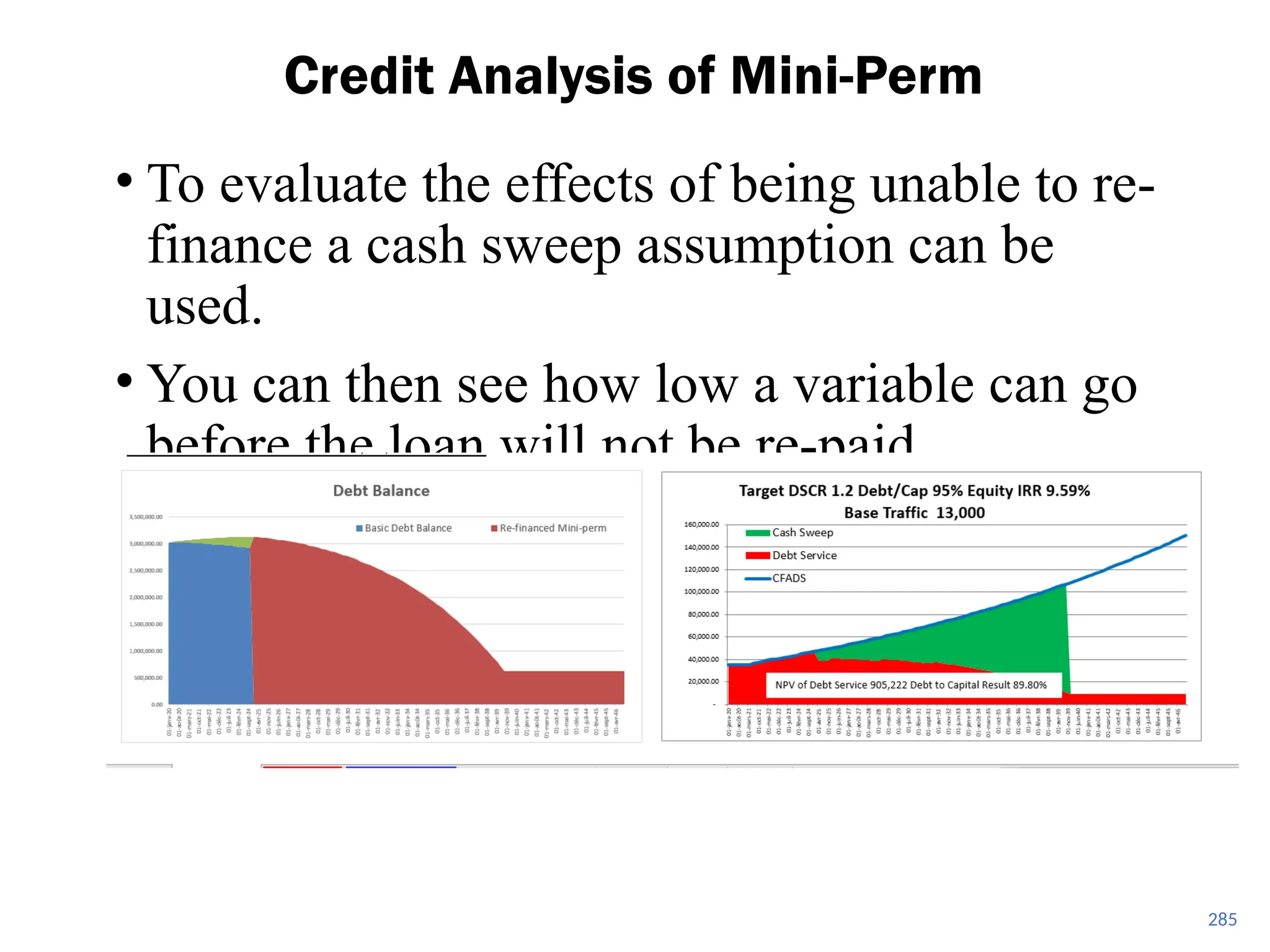

![Fundamental Formulas for Credit in Project Finance for DSCR,

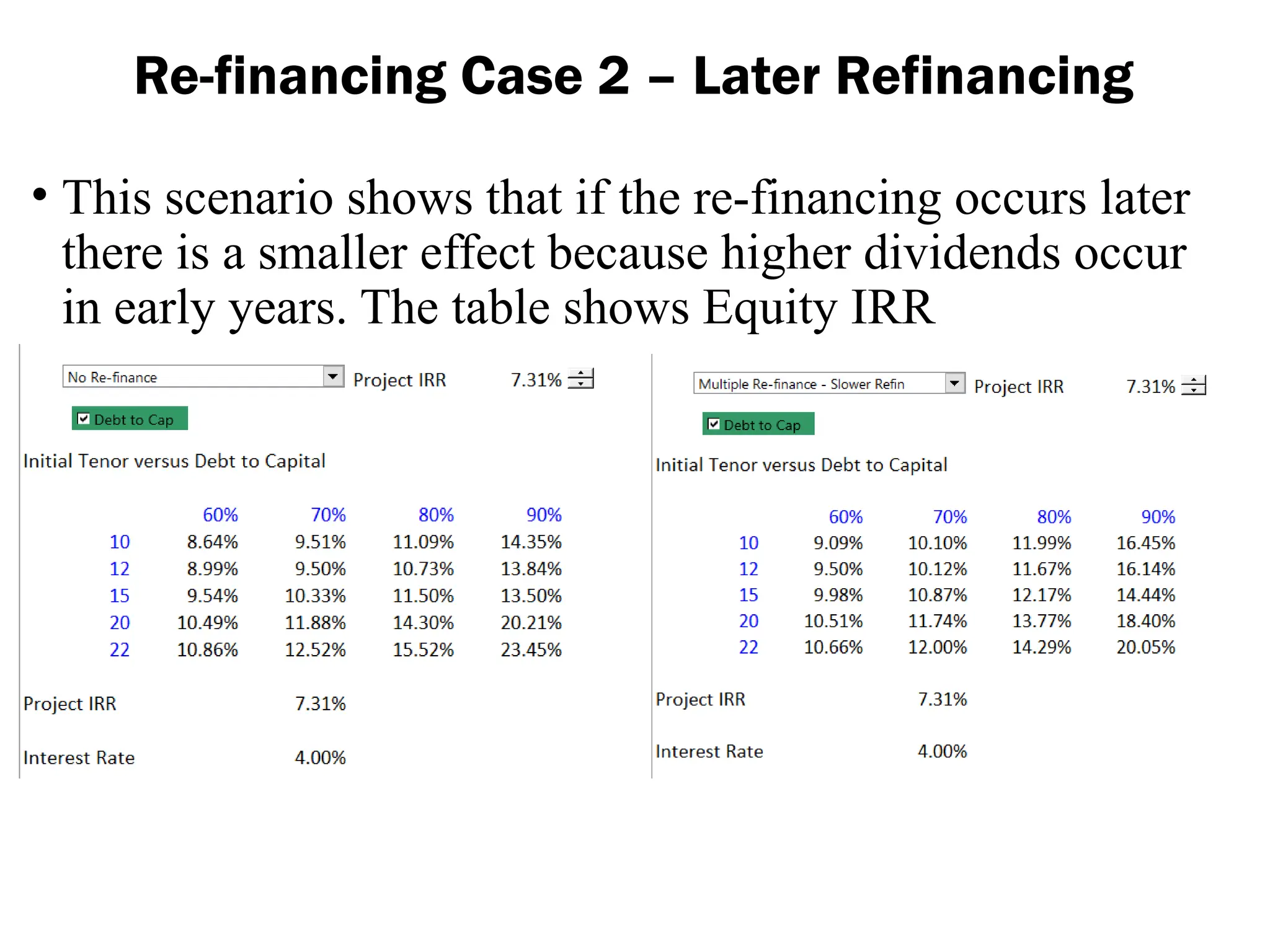

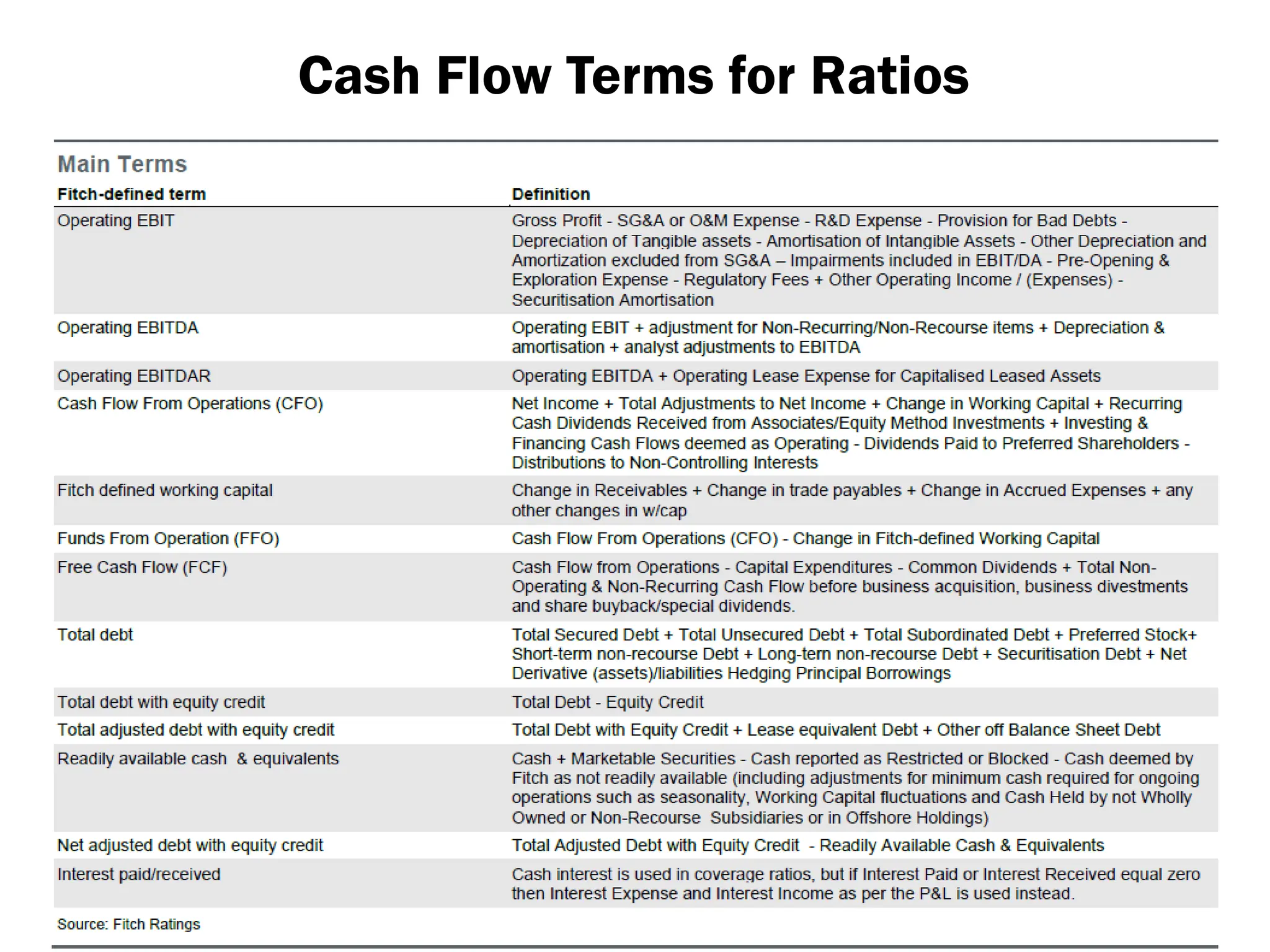

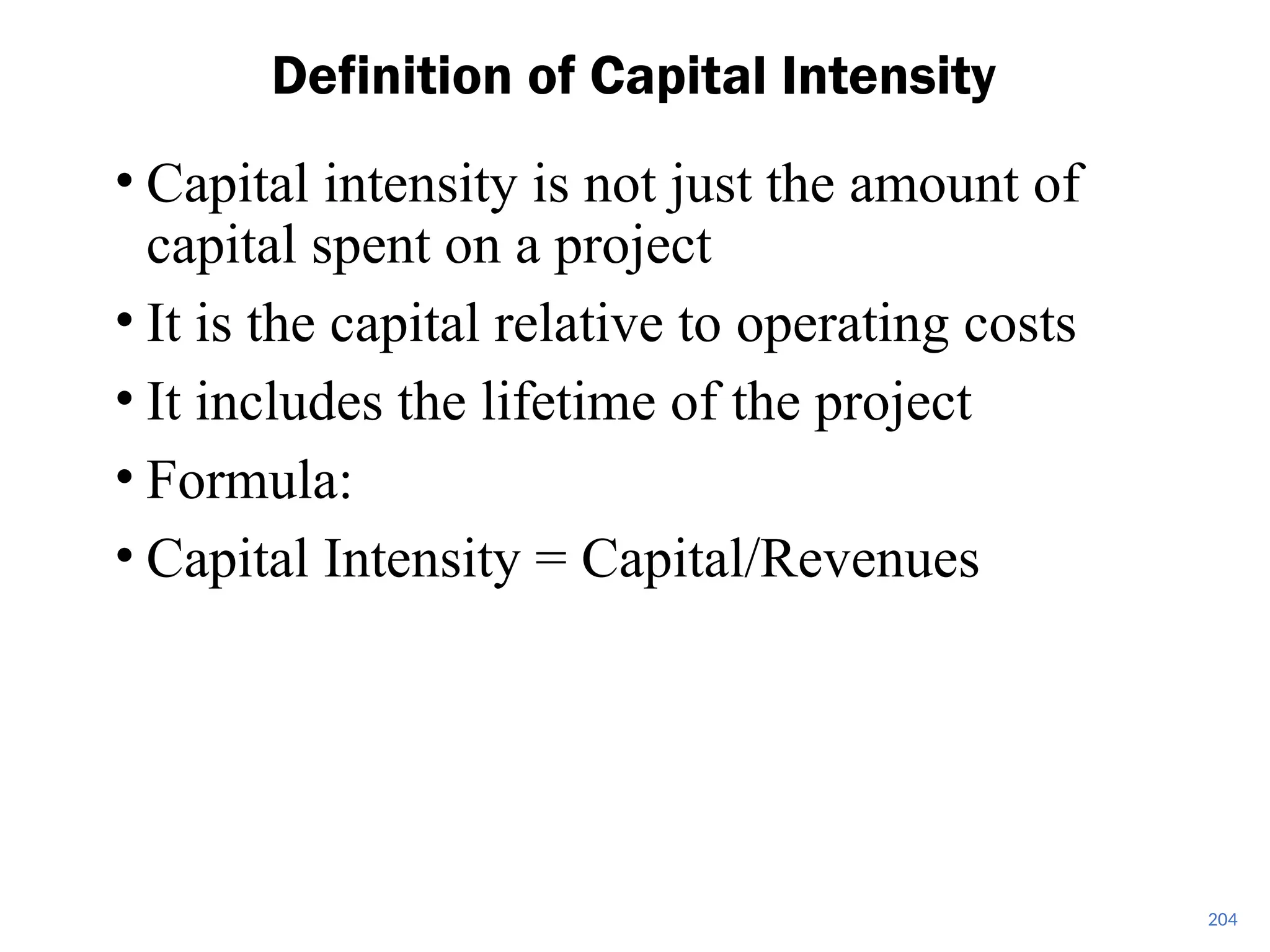

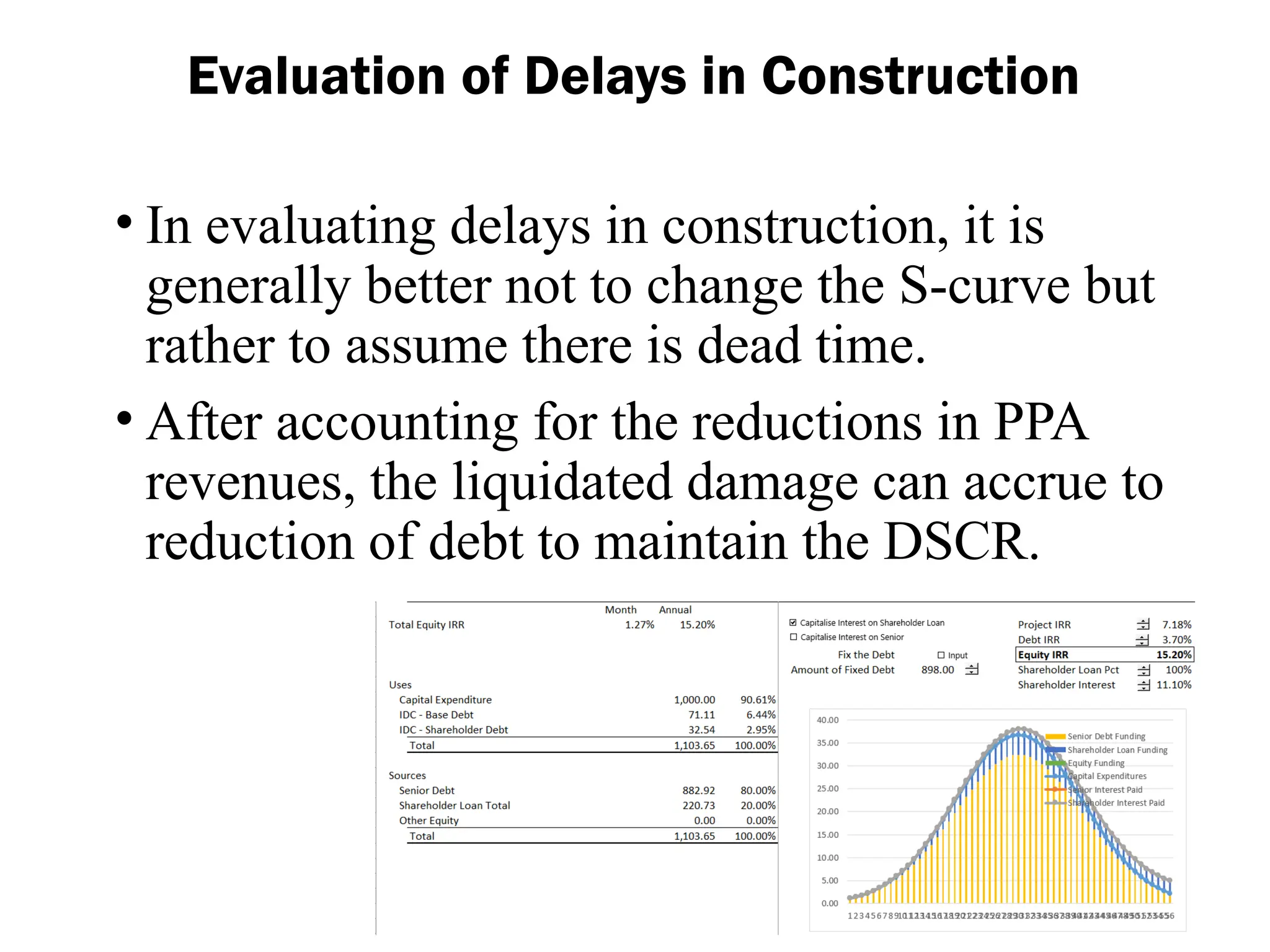

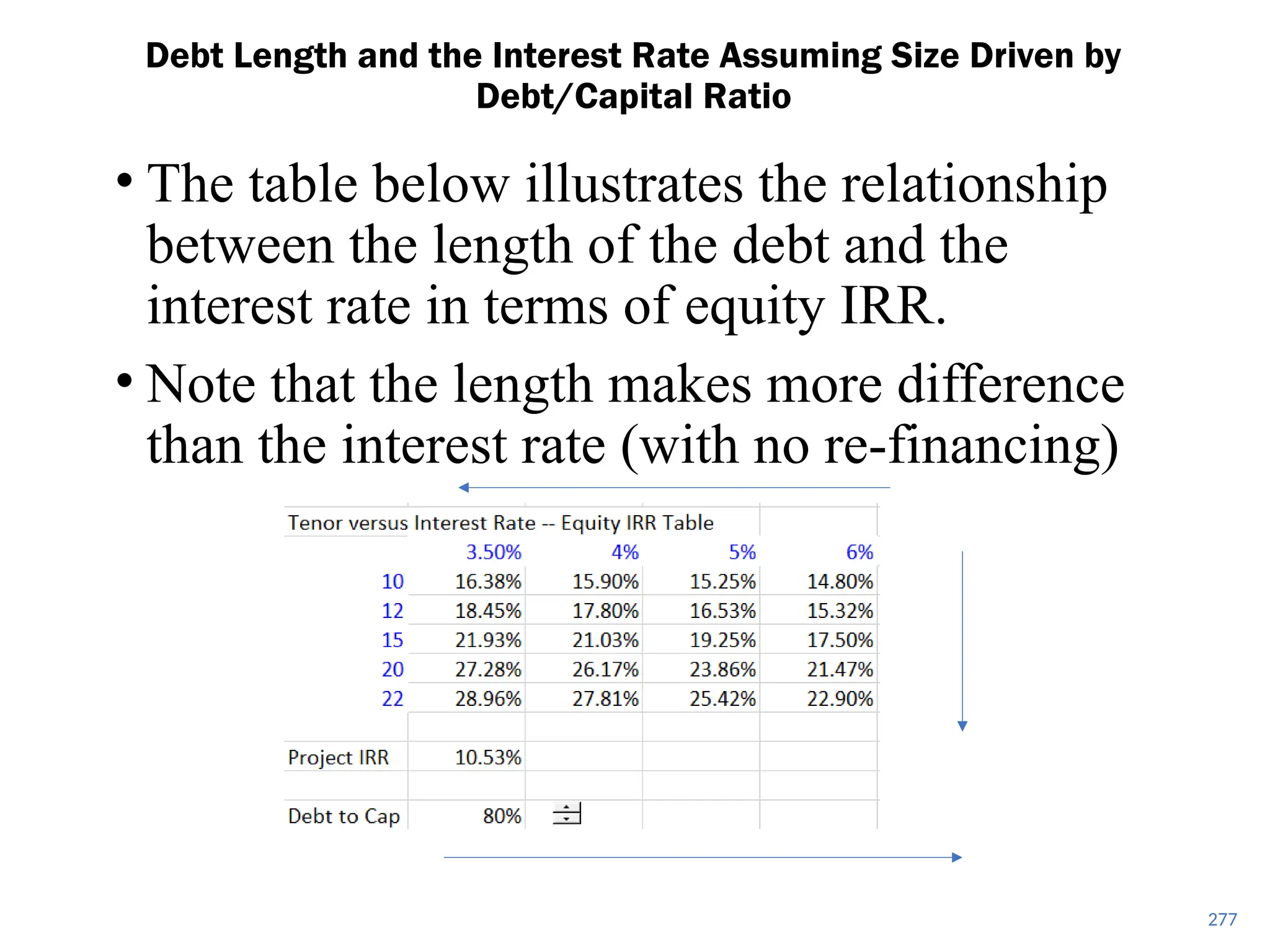

LLCR and PLCR

• DSCR = Cash Flow Available for Debt Service/[Debt Service]

• PLCR = PV(Cash Flow Available for Debt Service)/PV(Debt Service)

• LLCR = PV(Cash Flow Available for Debt Service over loan life)/PV(Debt

Service)

• Debt at COD = PV(Debt Service using Debt Interest Rate)

• Therefore,

• PLCR = PV(Cash Flow Available for Debt Service)/Debt - DSRA

• LLCR = PV(Cash Flow Available for Debt Service over loan life)/Debt – DSRA

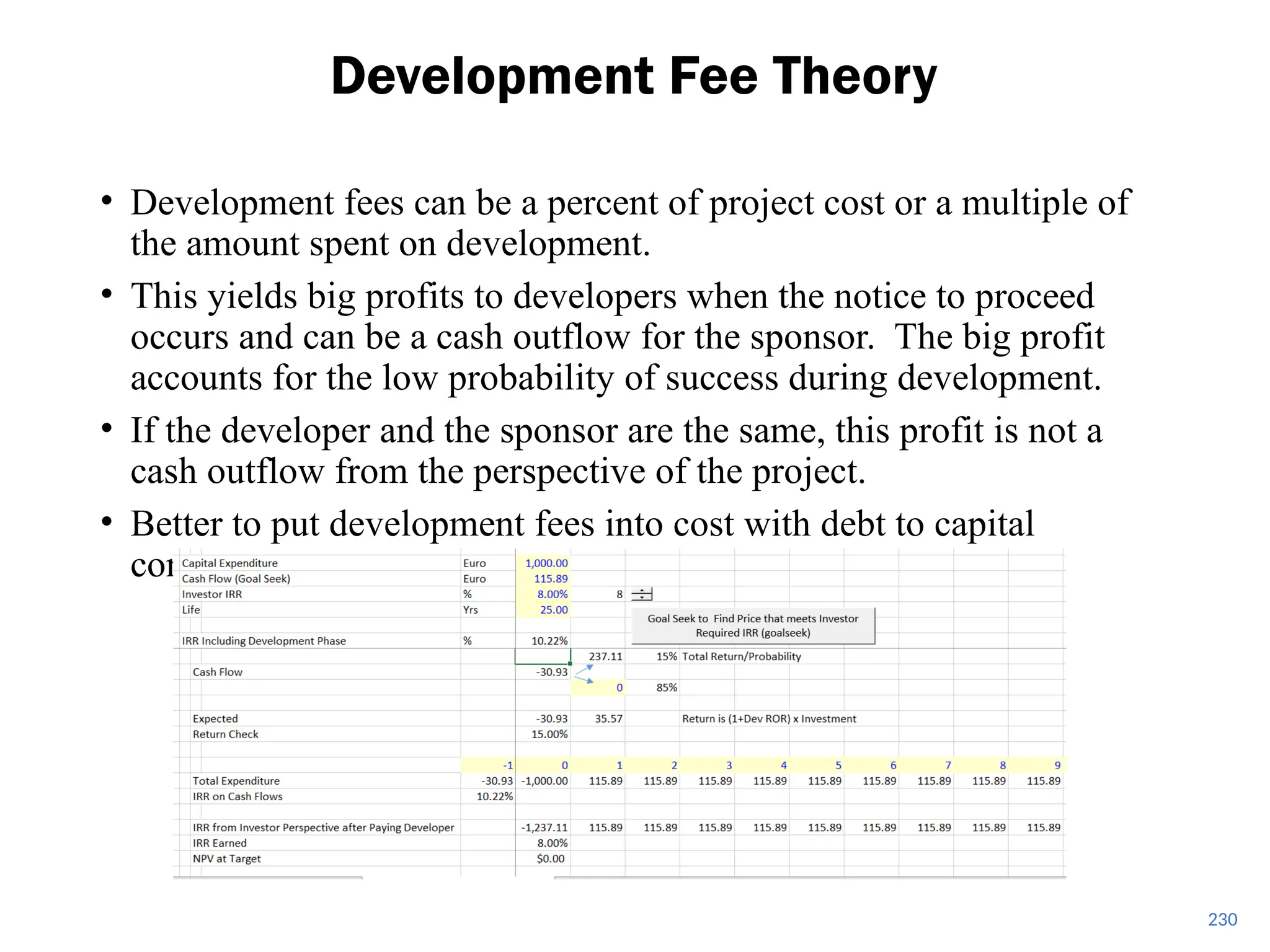

• Theory

• Minimum DSCR measures probability of default in one year

• LLCR measures coverage over the entire loan life even if project must be re-

structured

• PLCR measures coverage over the entire project life and the value of the tail](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/project-finance-2-1-250115111236-848ba4b7/75/Project-Finance-2-1-Basics-of-Project-Finance-143-2048.jpg)

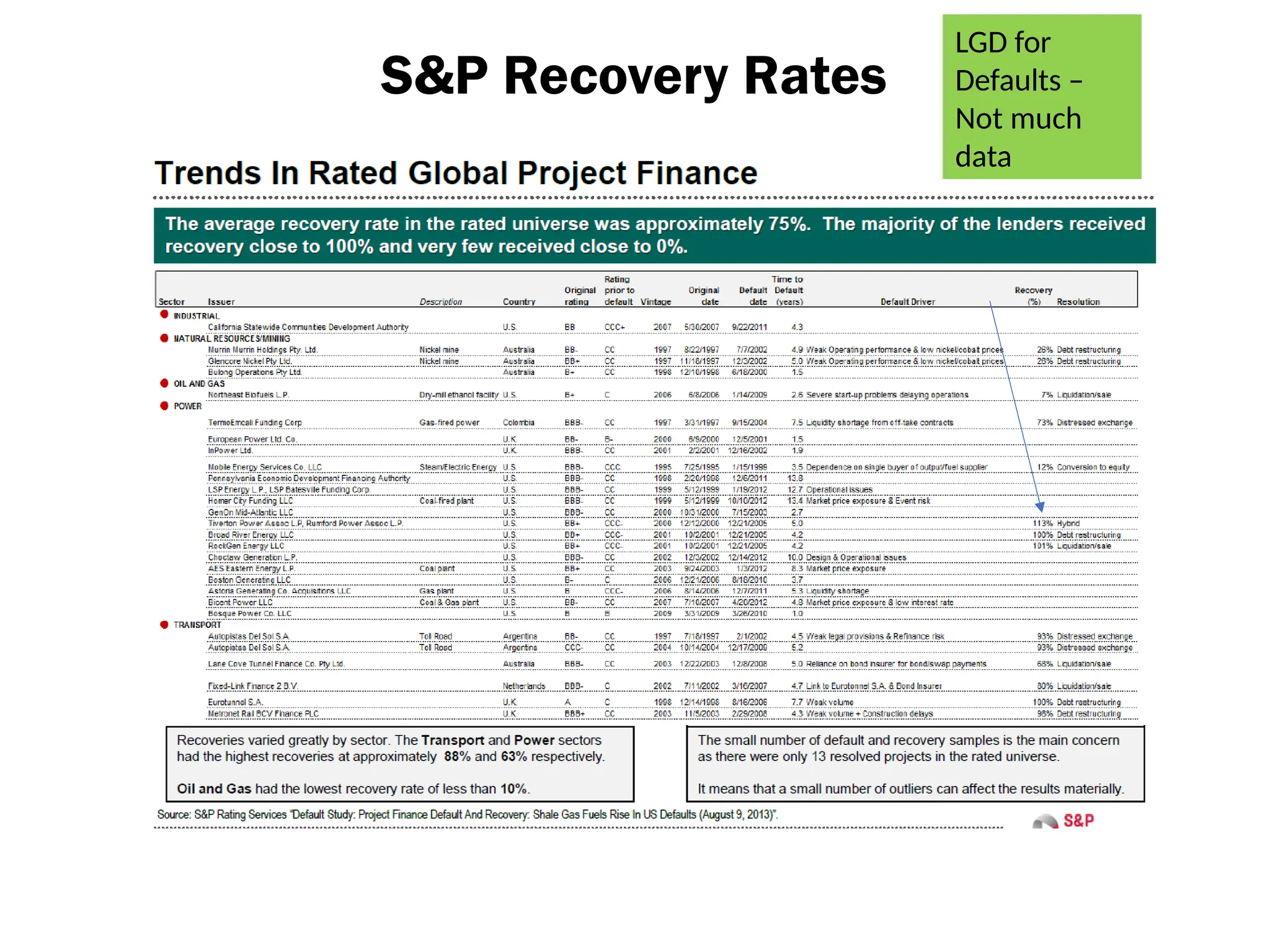

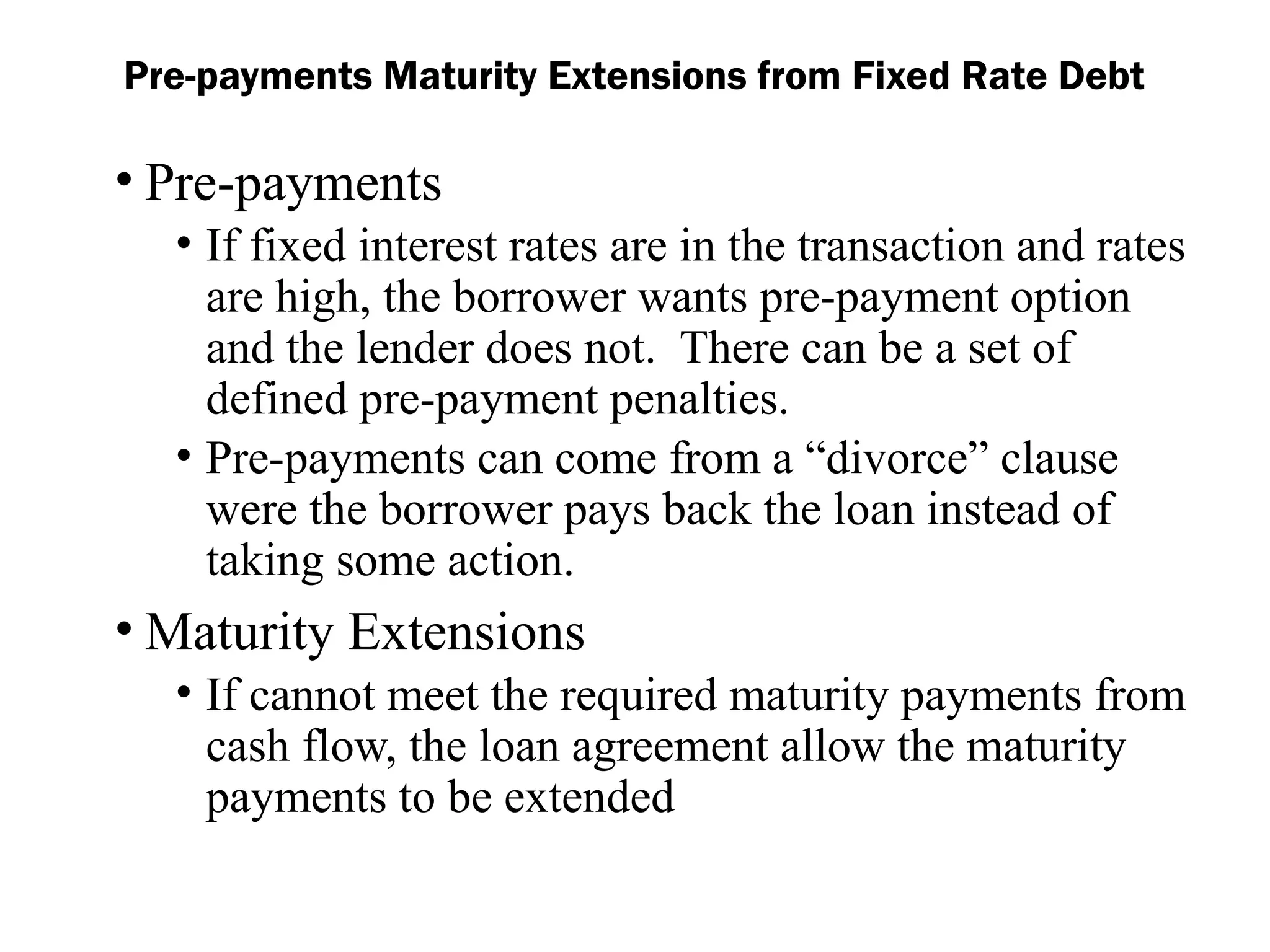

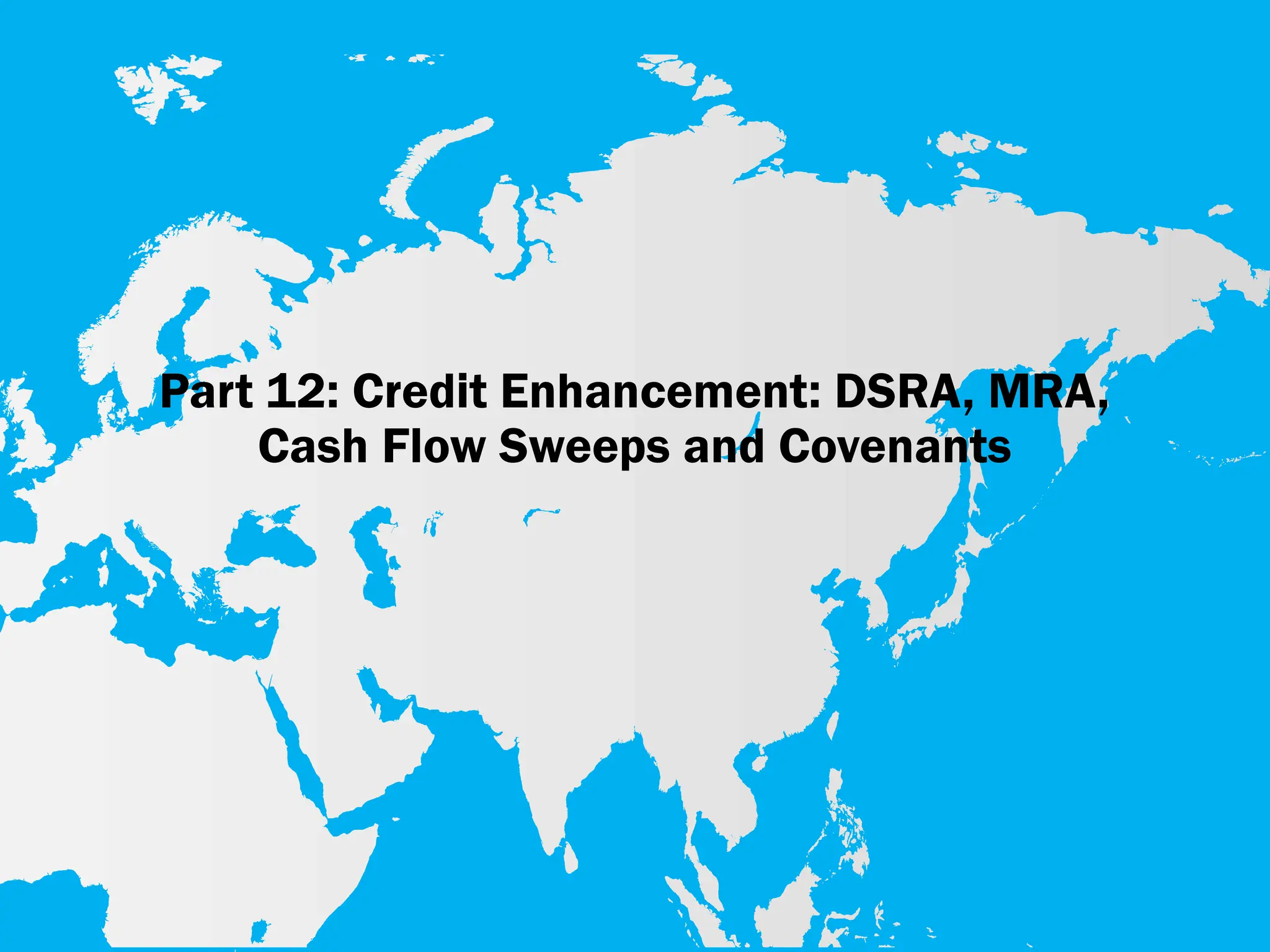

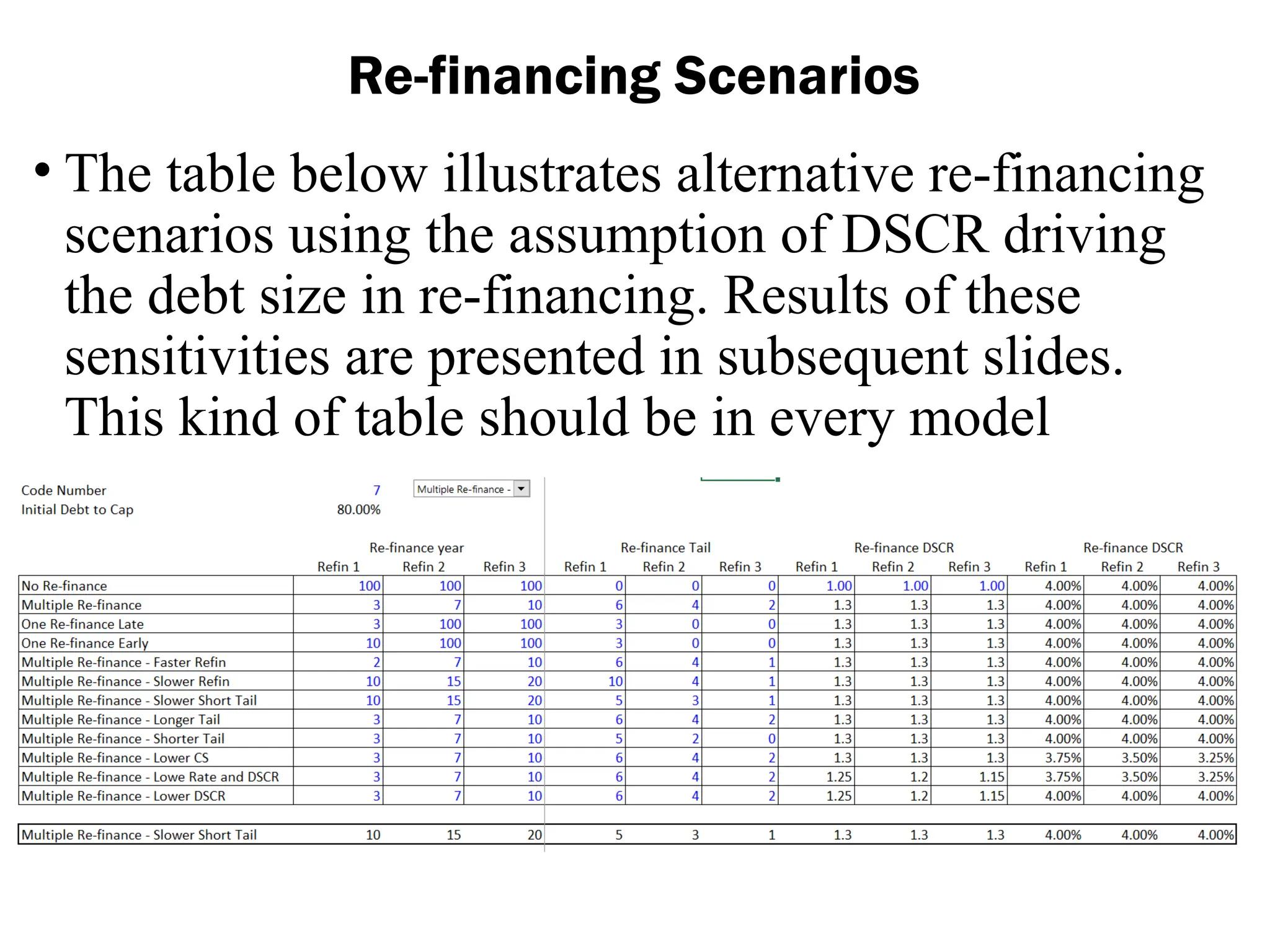

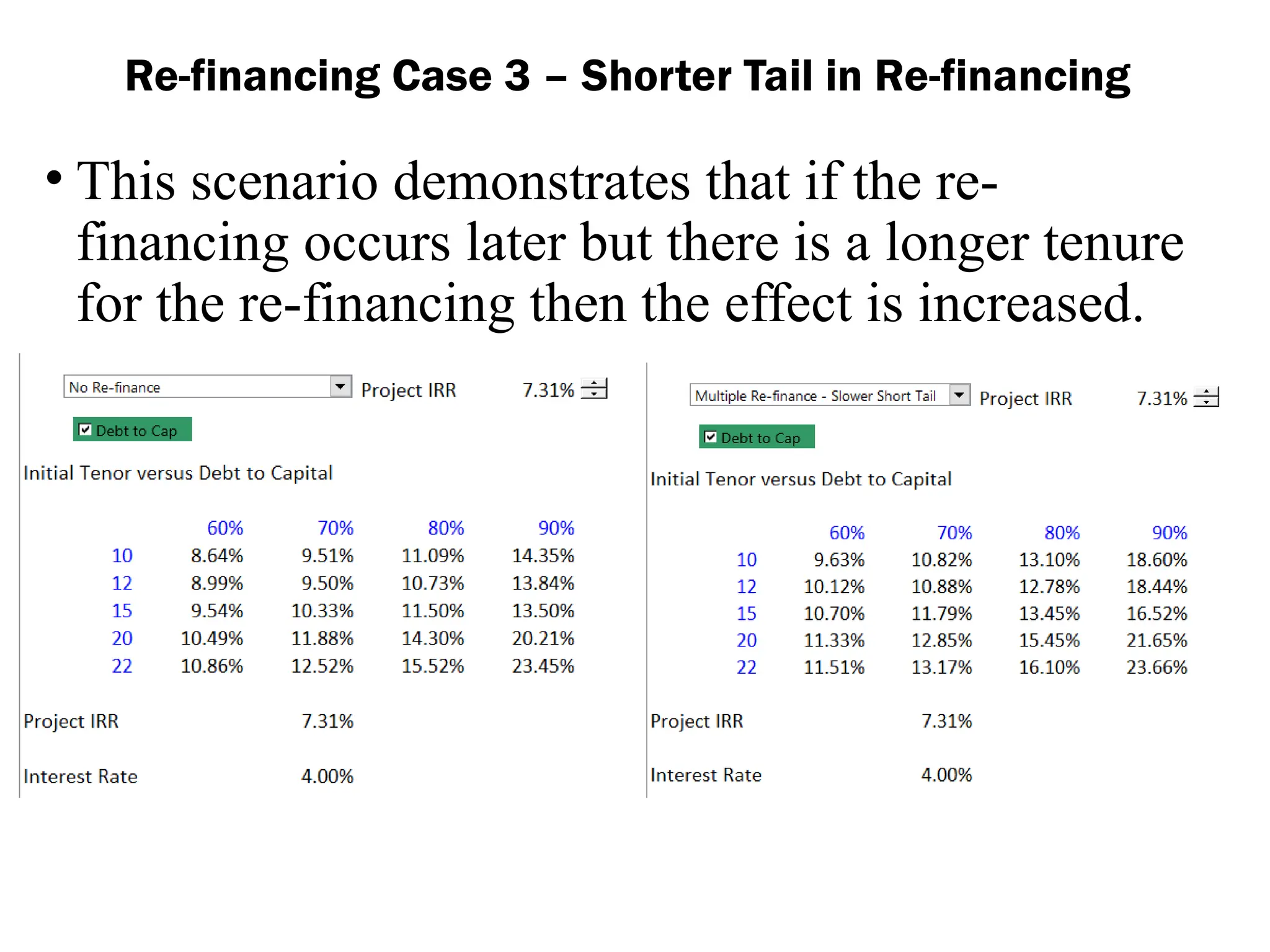

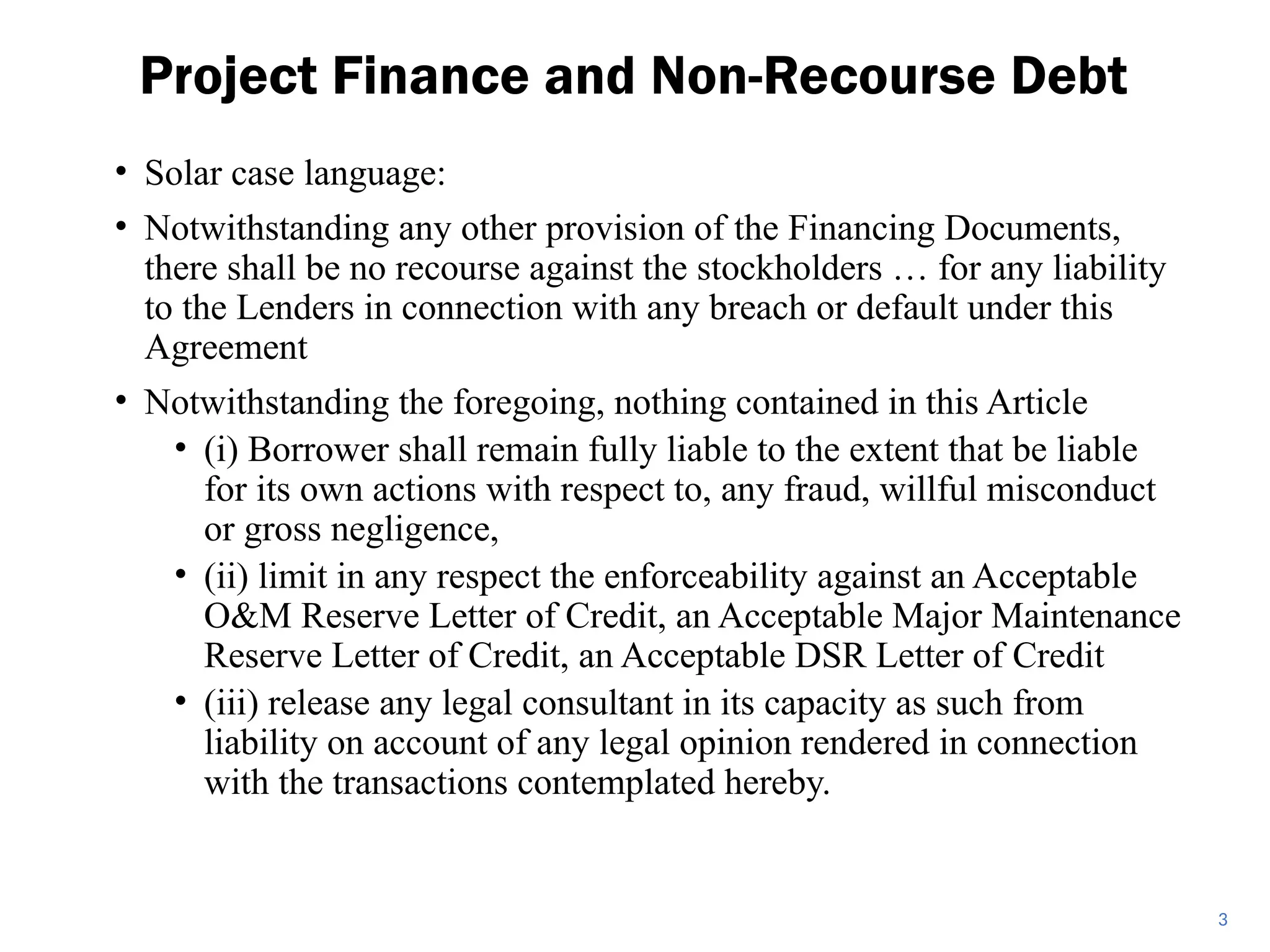

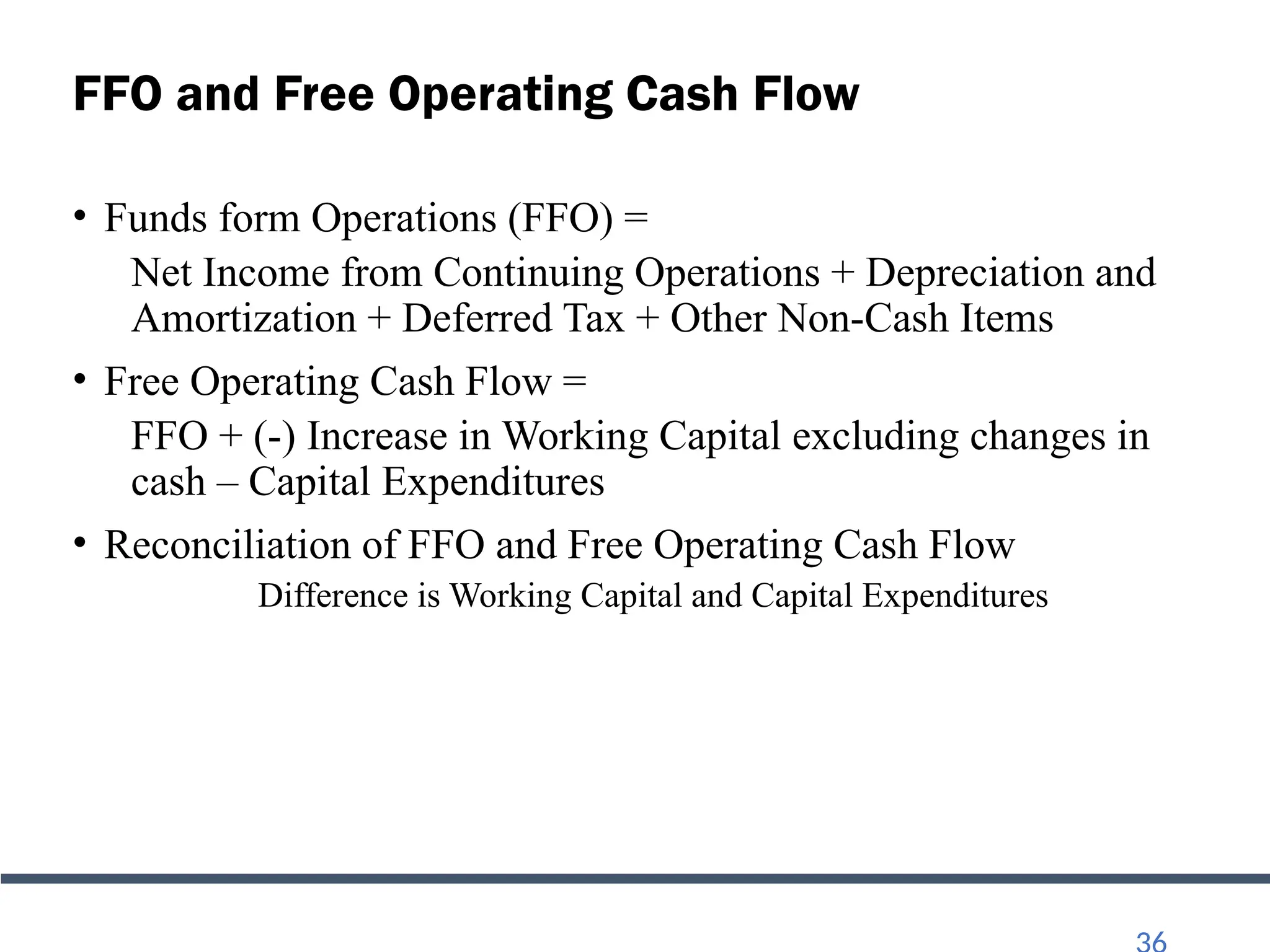

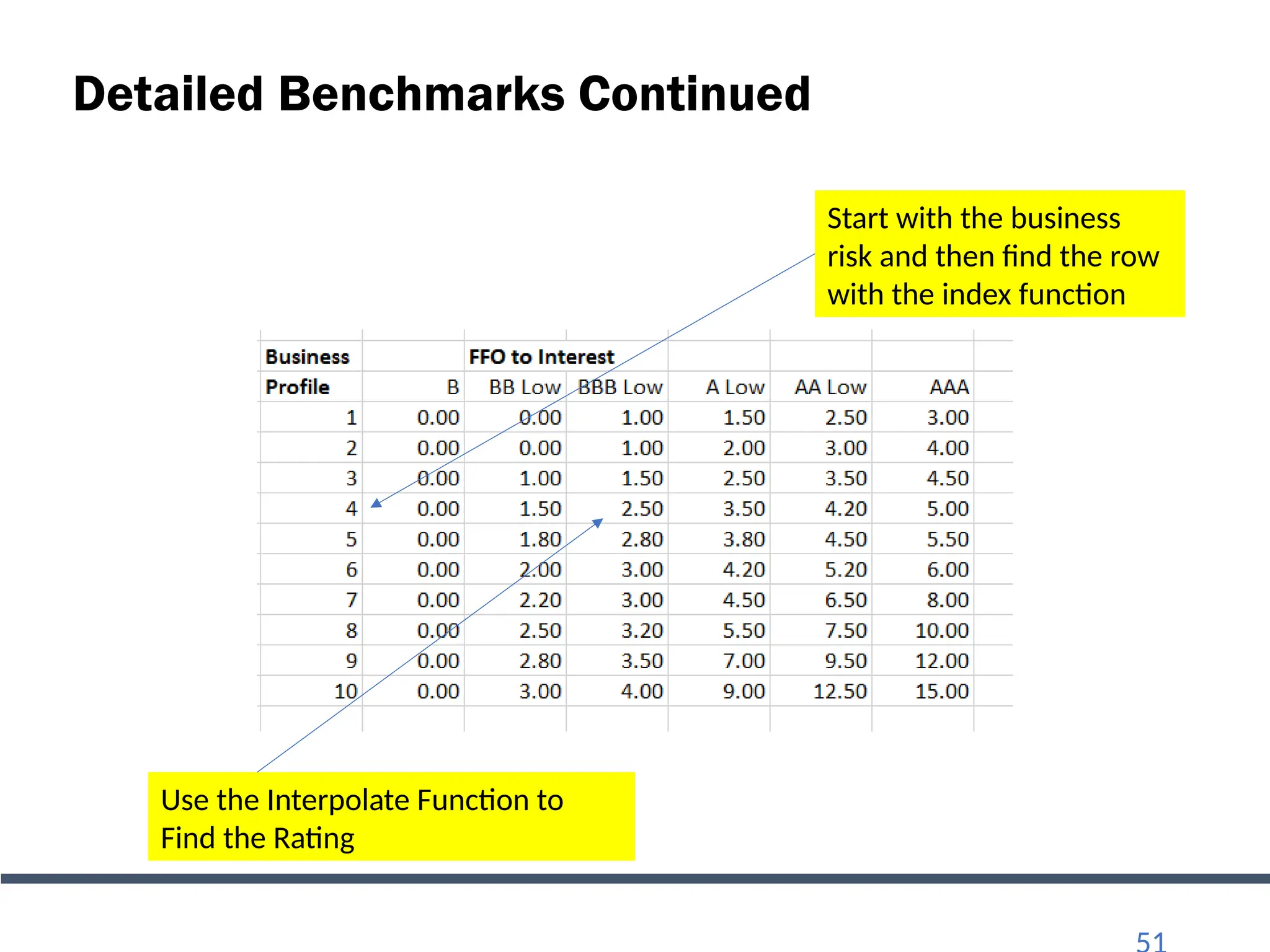

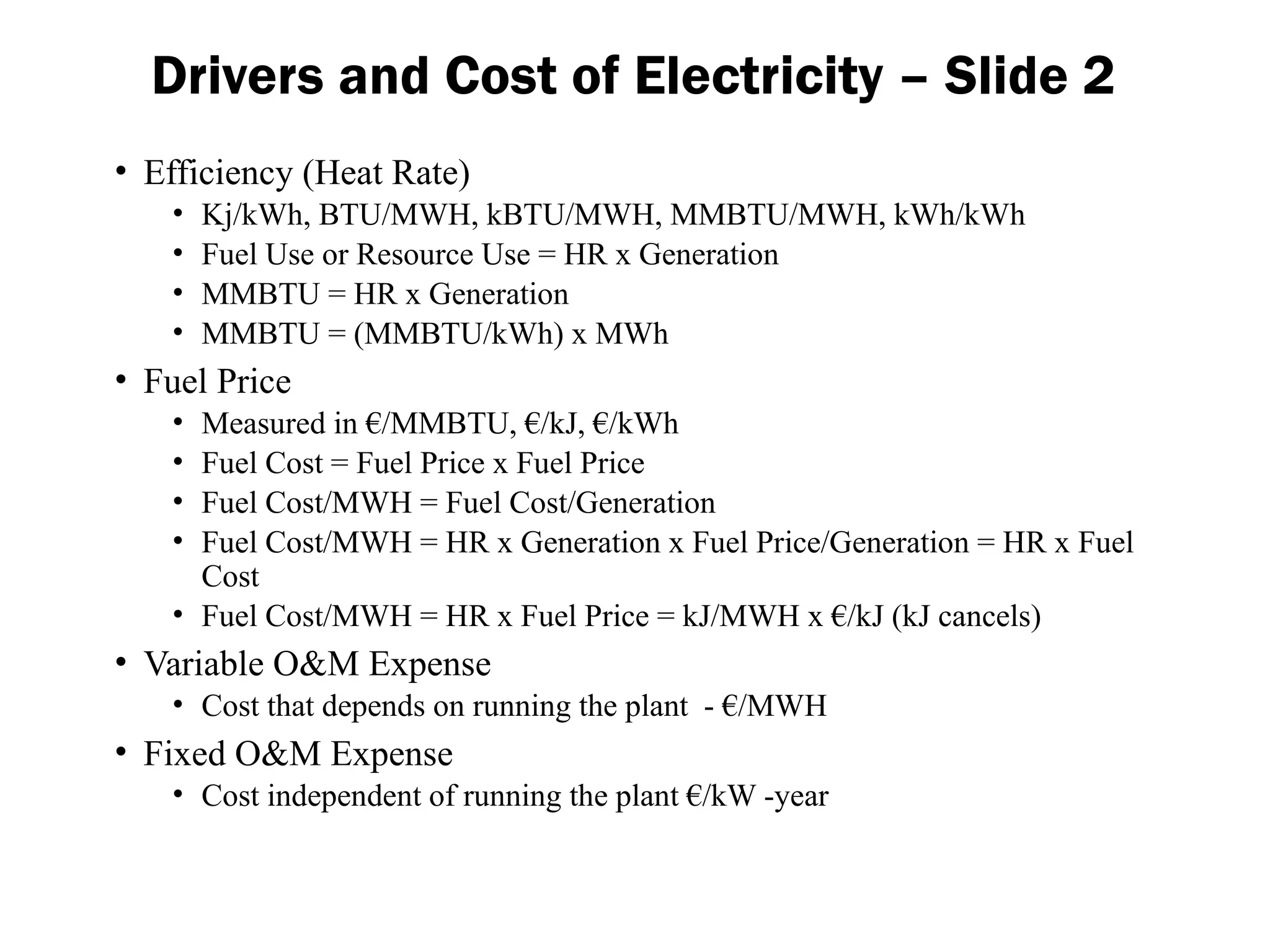

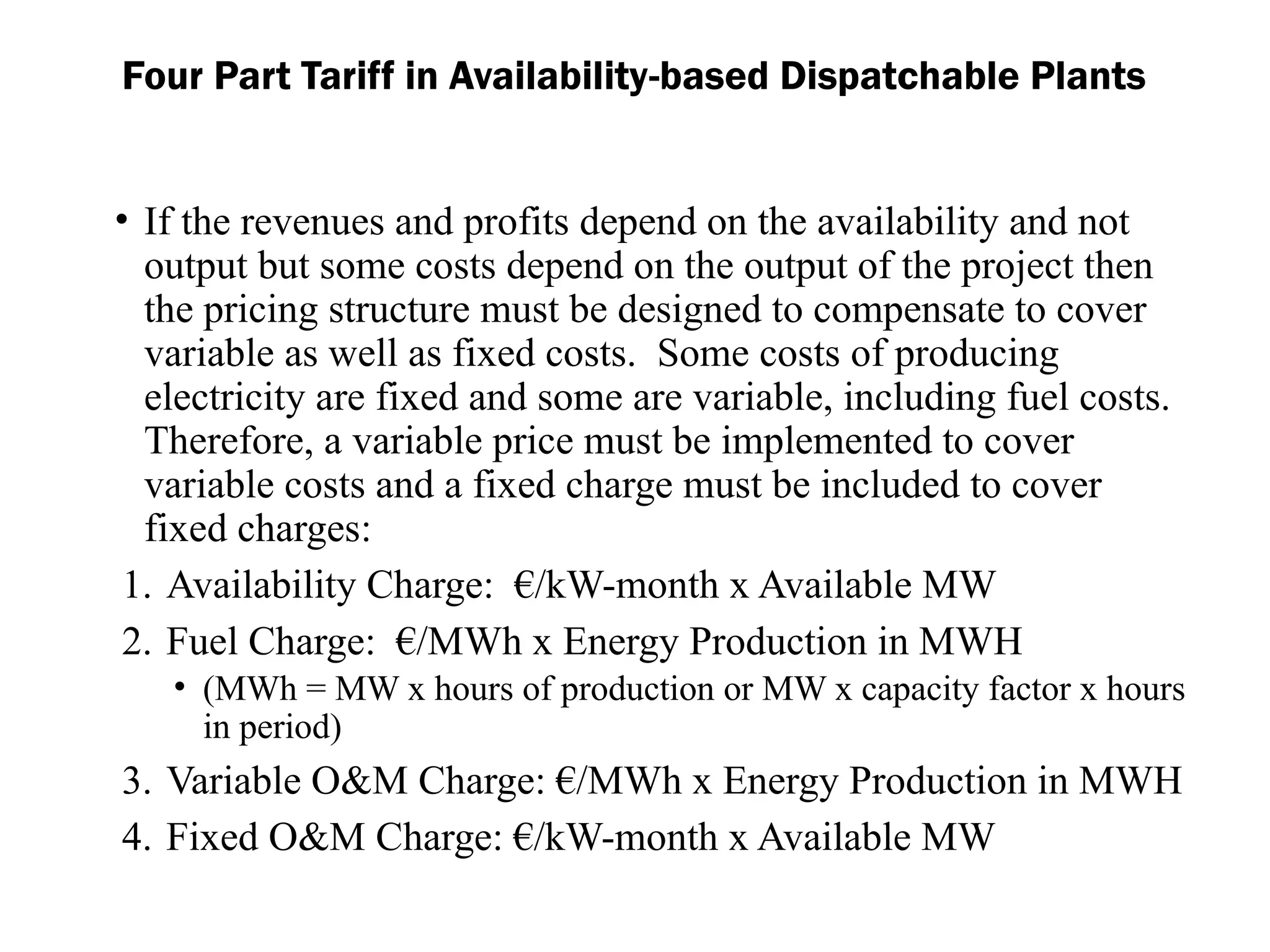

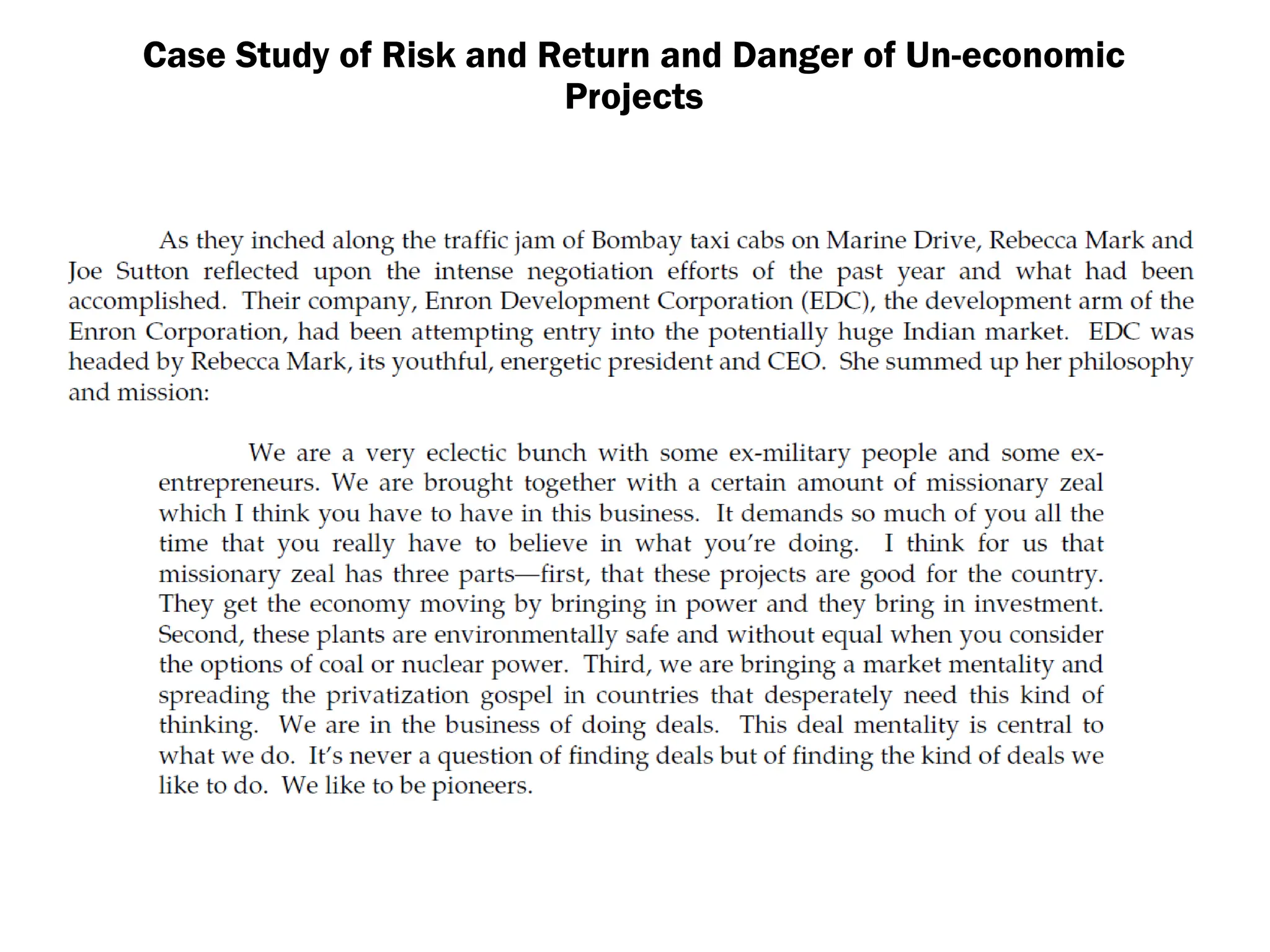

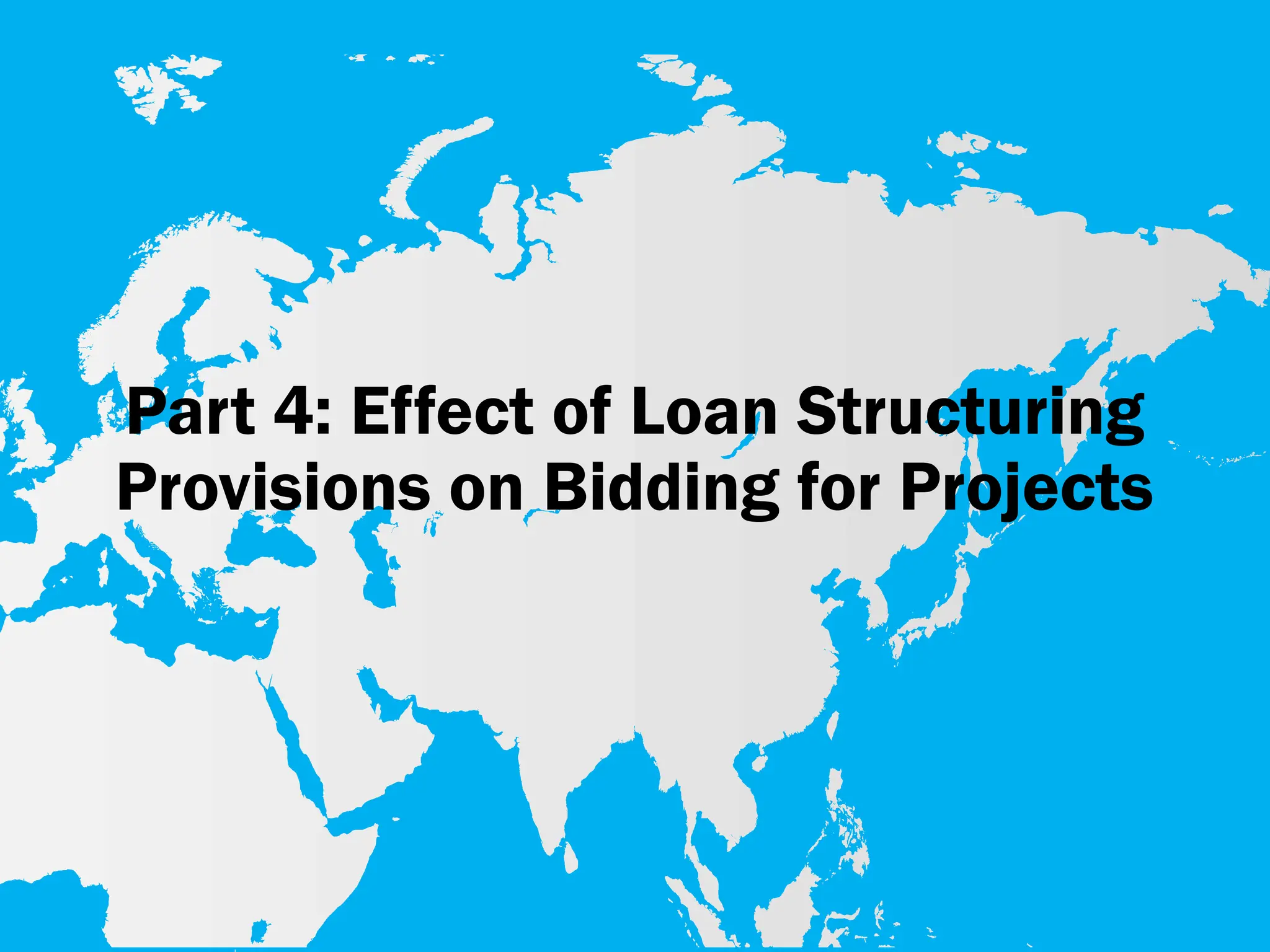

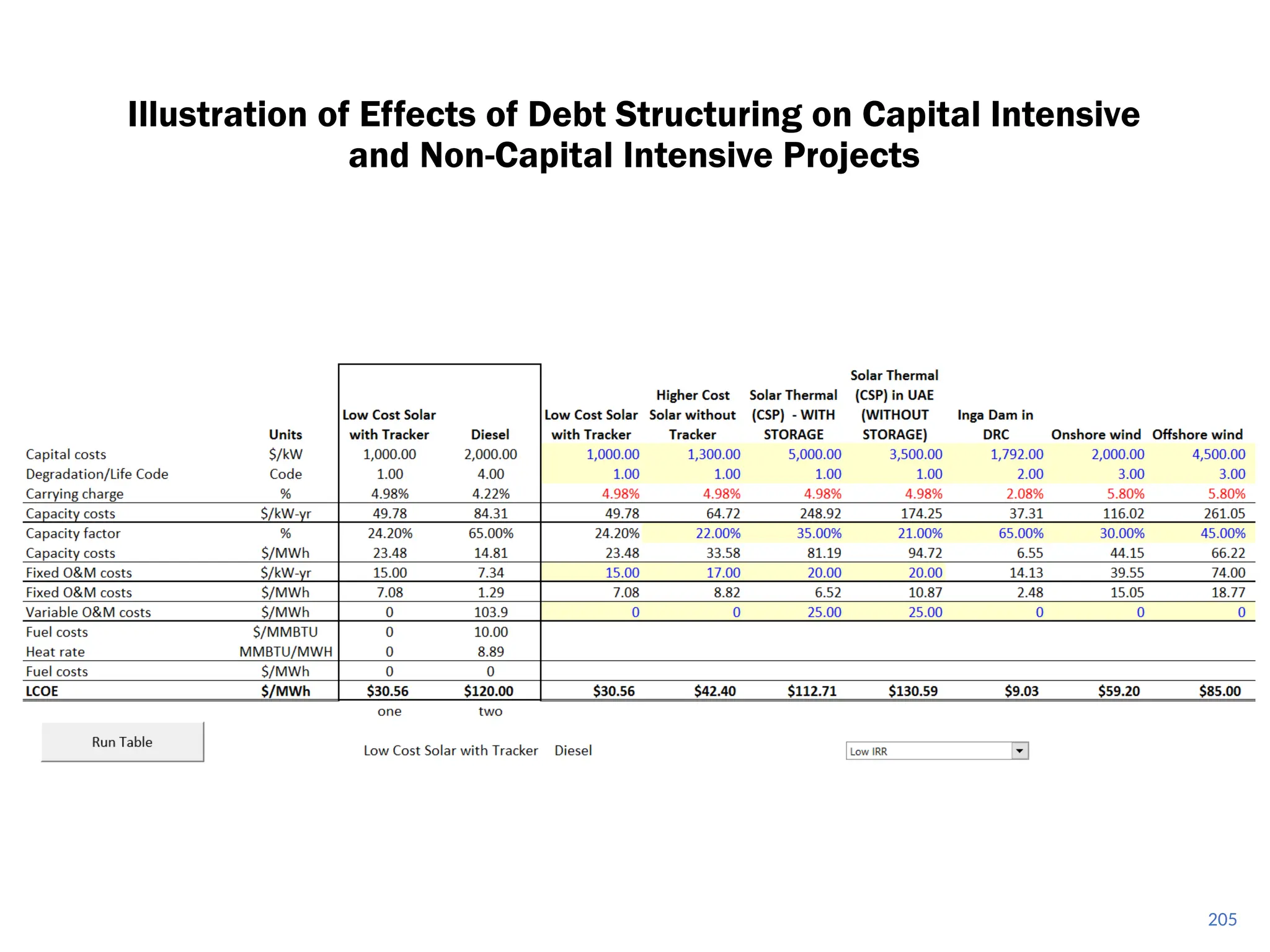

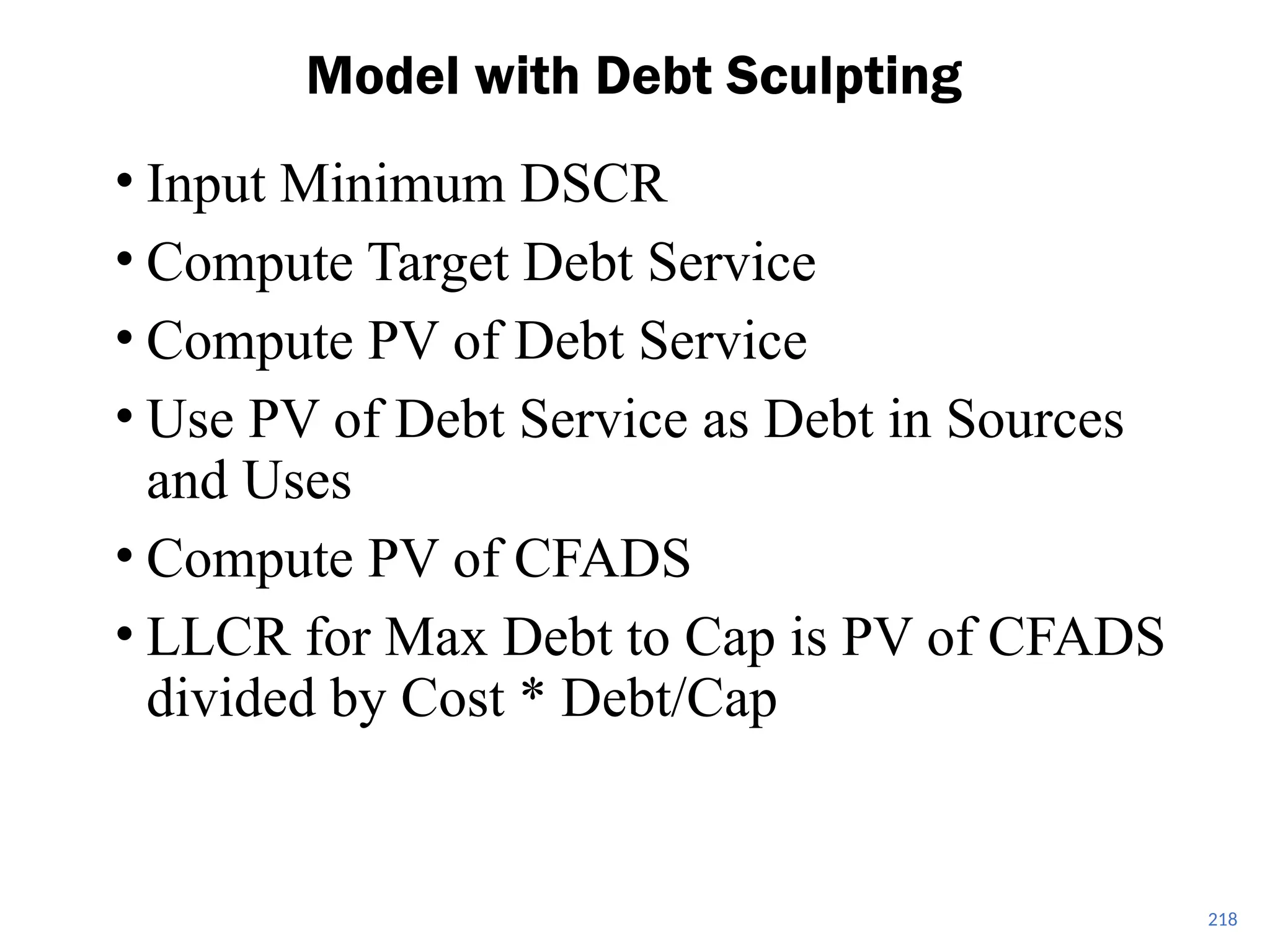

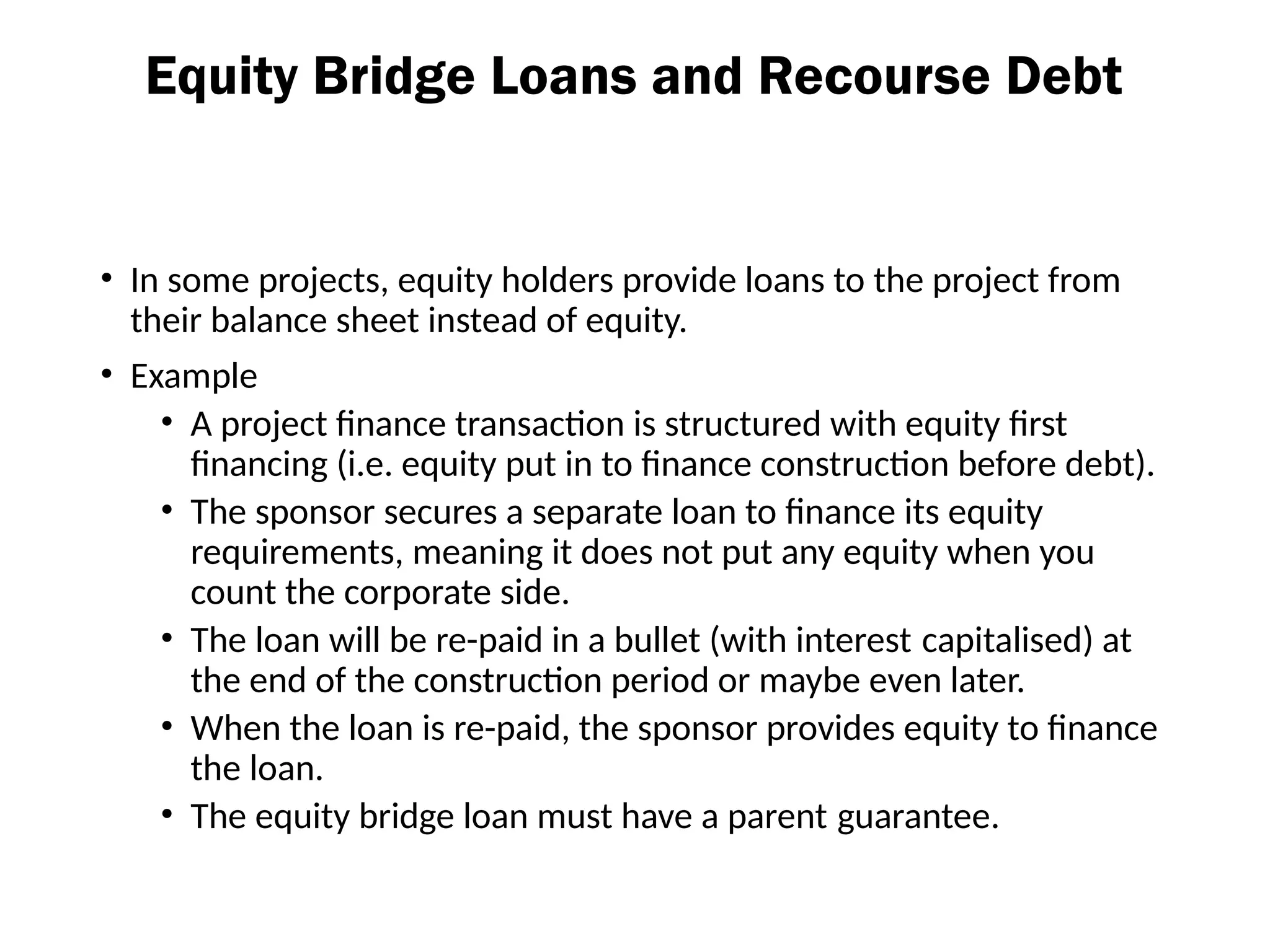

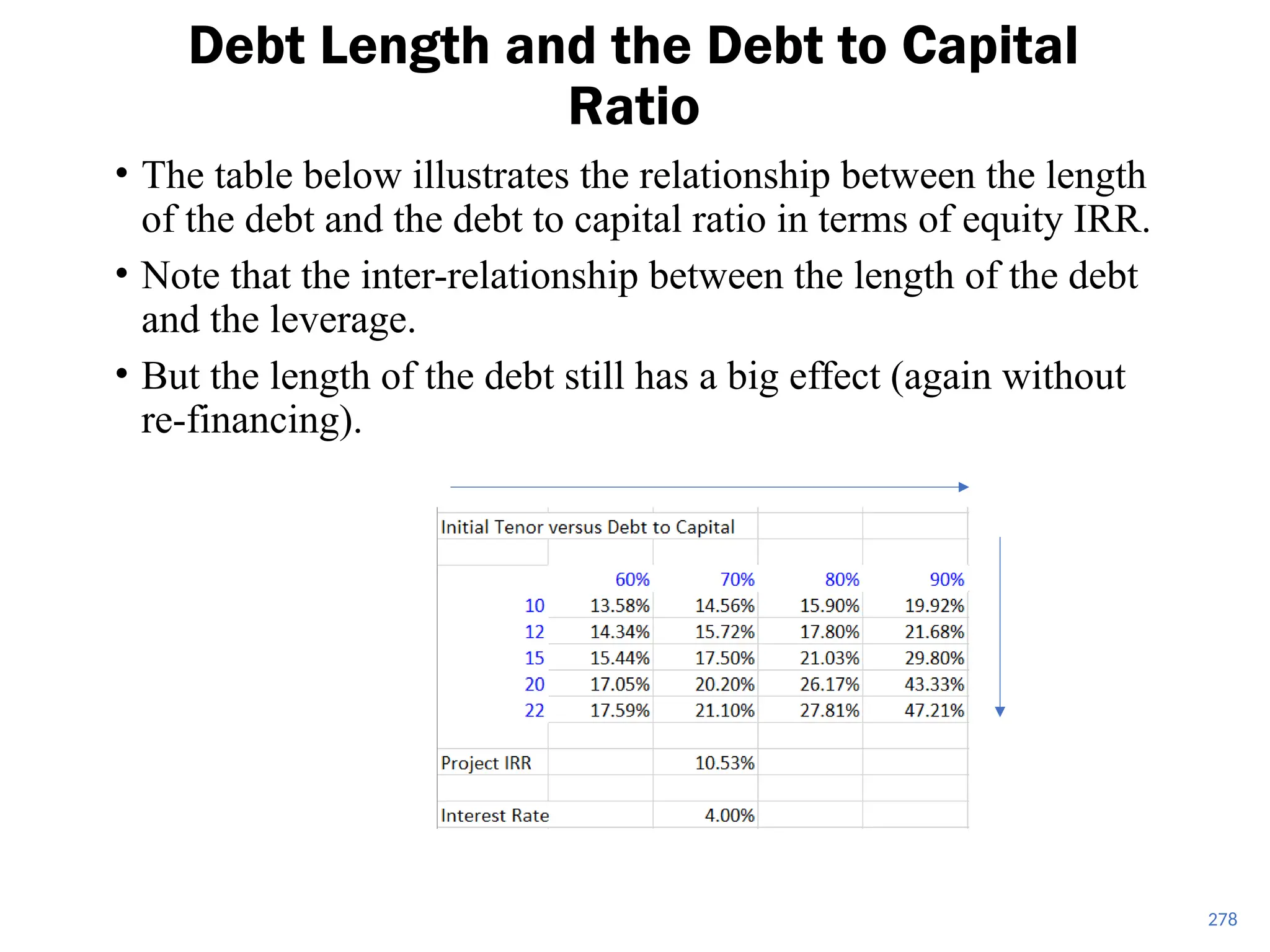

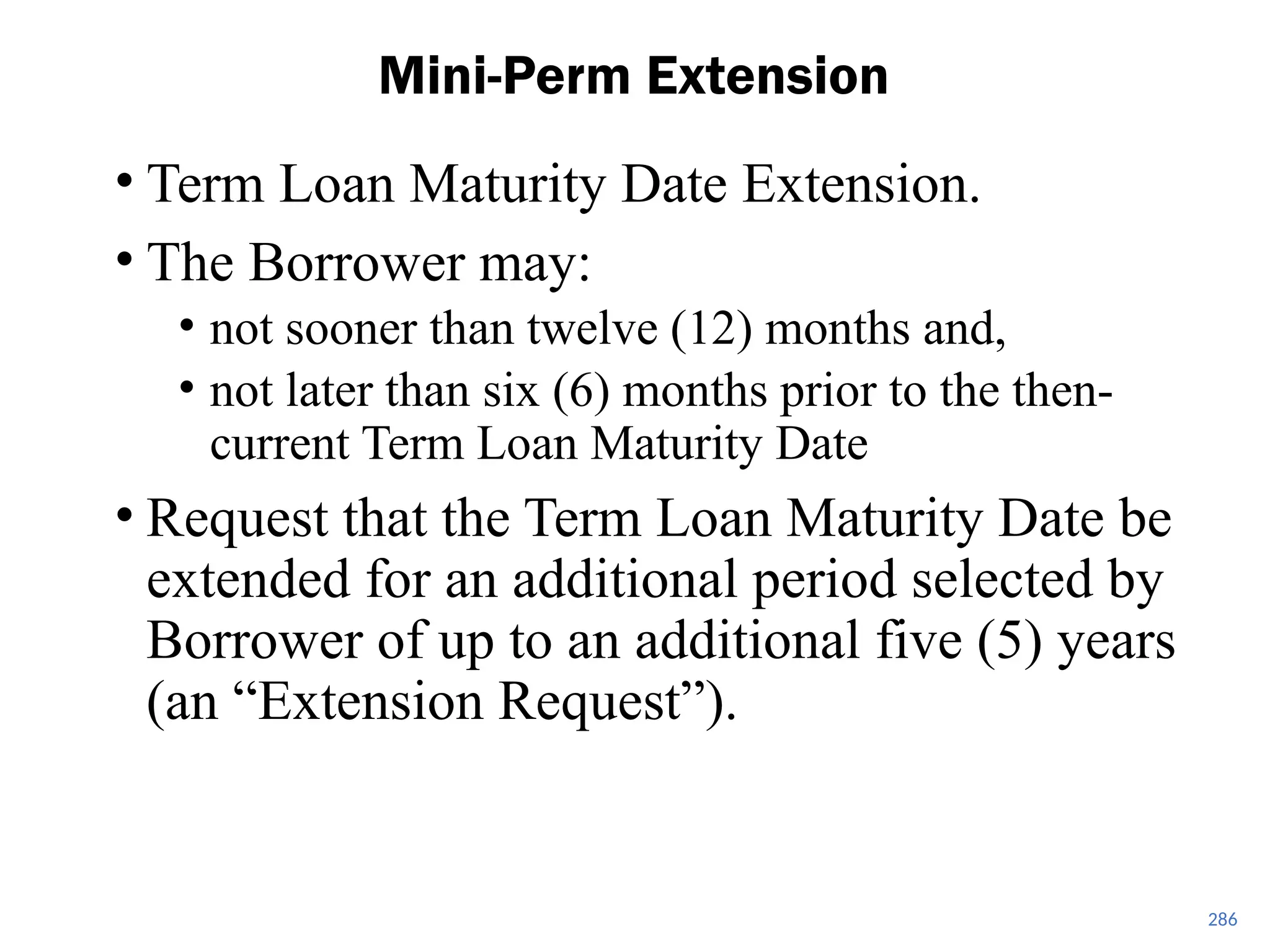

![• Prior to satisfying the options conditions, it is the

usual practice for the financiers to:

• be able to rely on other contractual or financial resources

(recourse or some kind of support from sponsors) to repay

that funding [if the project fails to be completed];

• If equity is not up-front may require letter of credit,

sponsor guarantee or really strong EPC contract; and,

• to roll up the capitalized interest-during-construction

(“IDC”) into the financing (i.e. capitalizing interest).

• During the construction phase, equity and debt funds

are used to finance the project construction with

funds generated from the project cash flow covering

the operation period.

Project Finance Loans – Drawdown during Construction

(Reference)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/project-finance-2-1-250115111236-848ba4b7/75/Project-Finance-2-1-Basics-of-Project-Finance-240-2048.jpg)

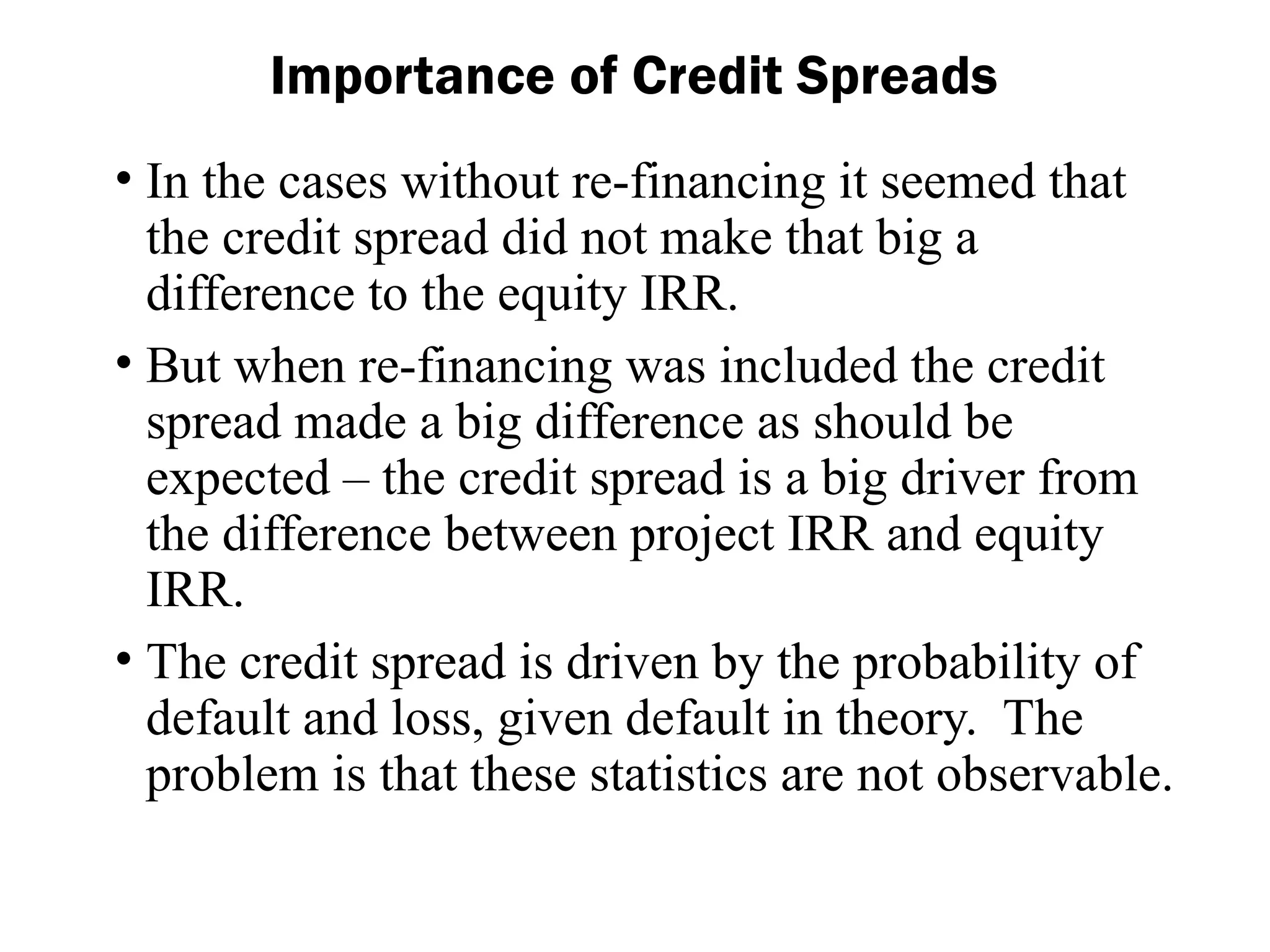

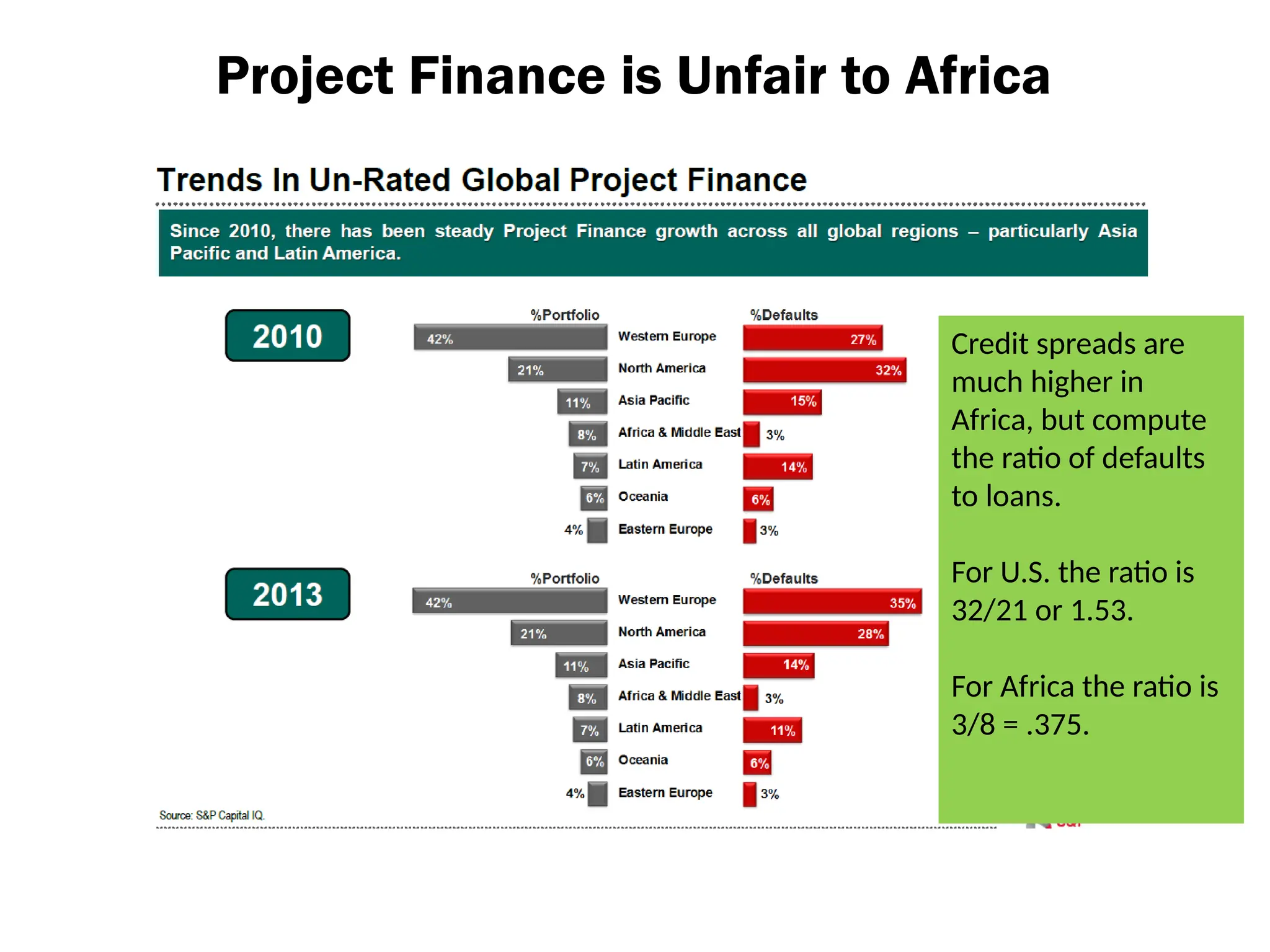

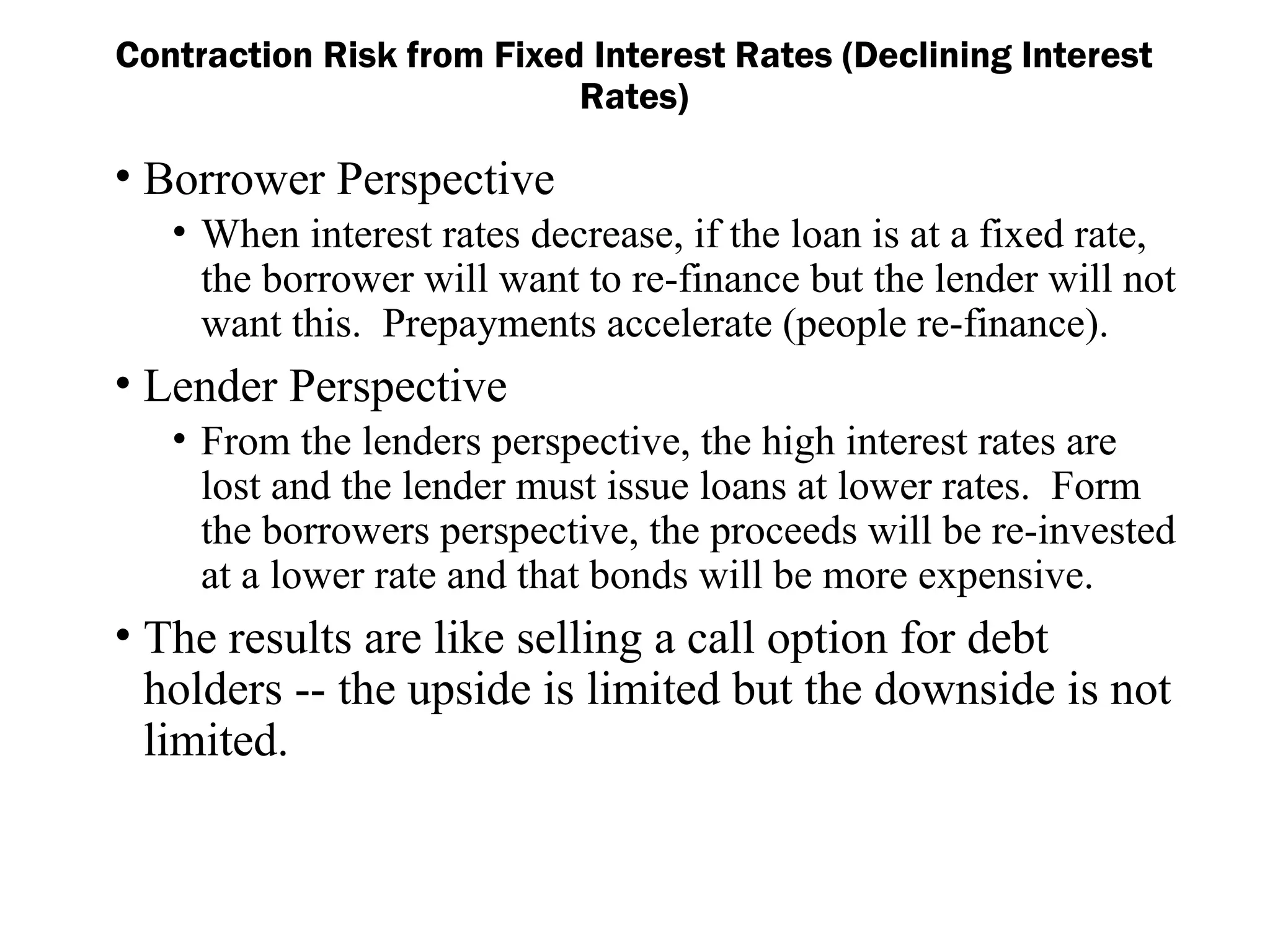

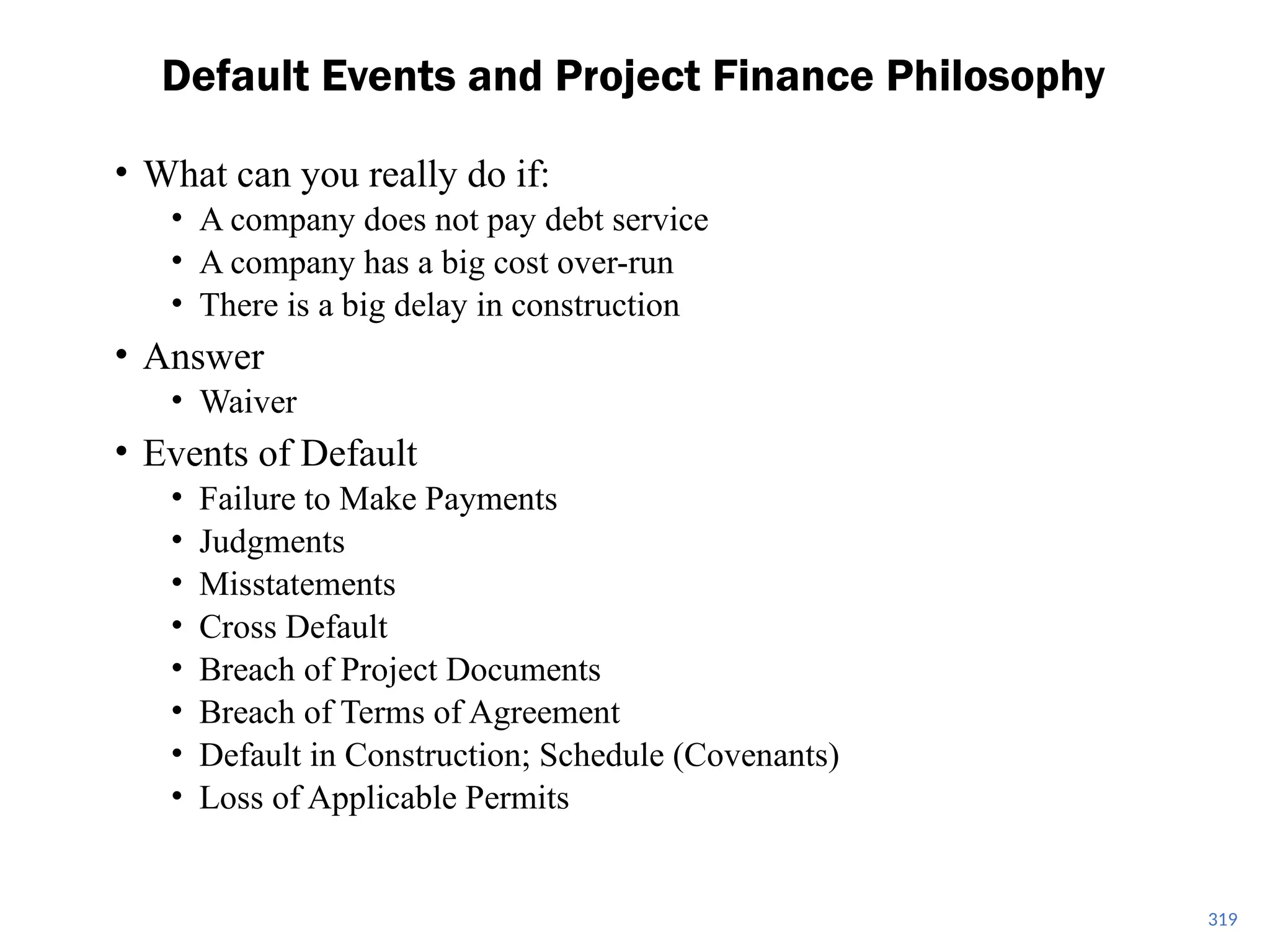

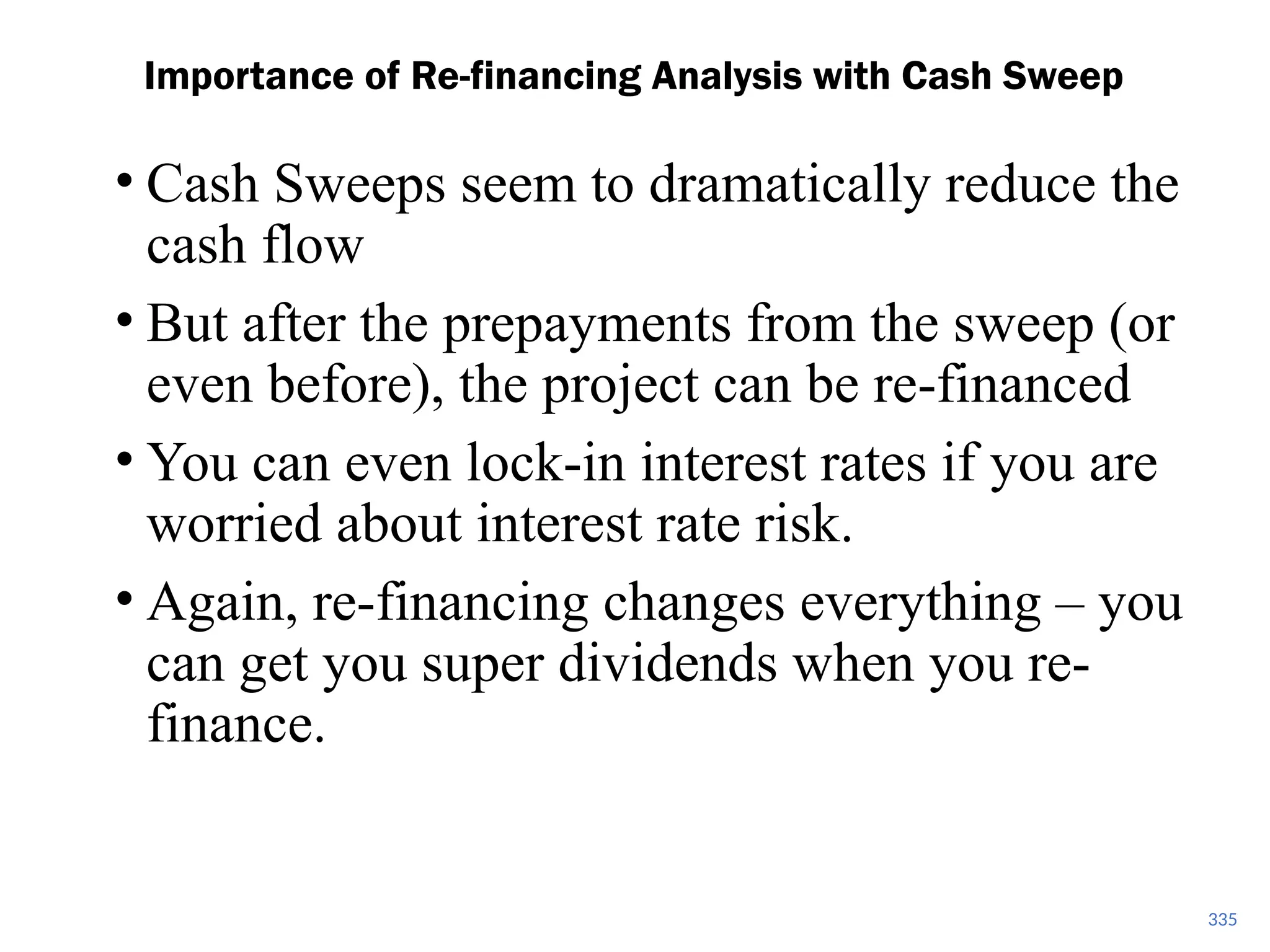

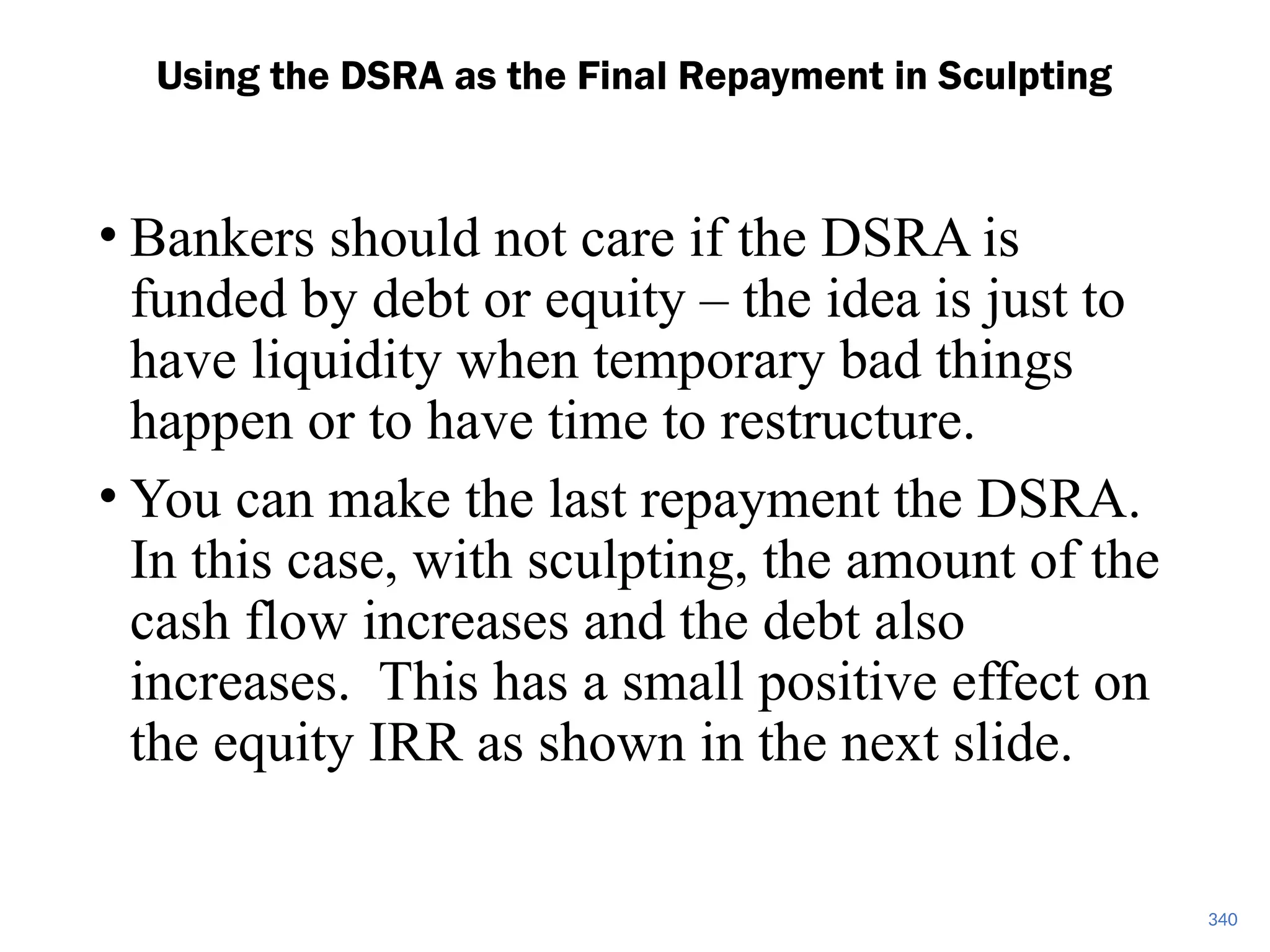

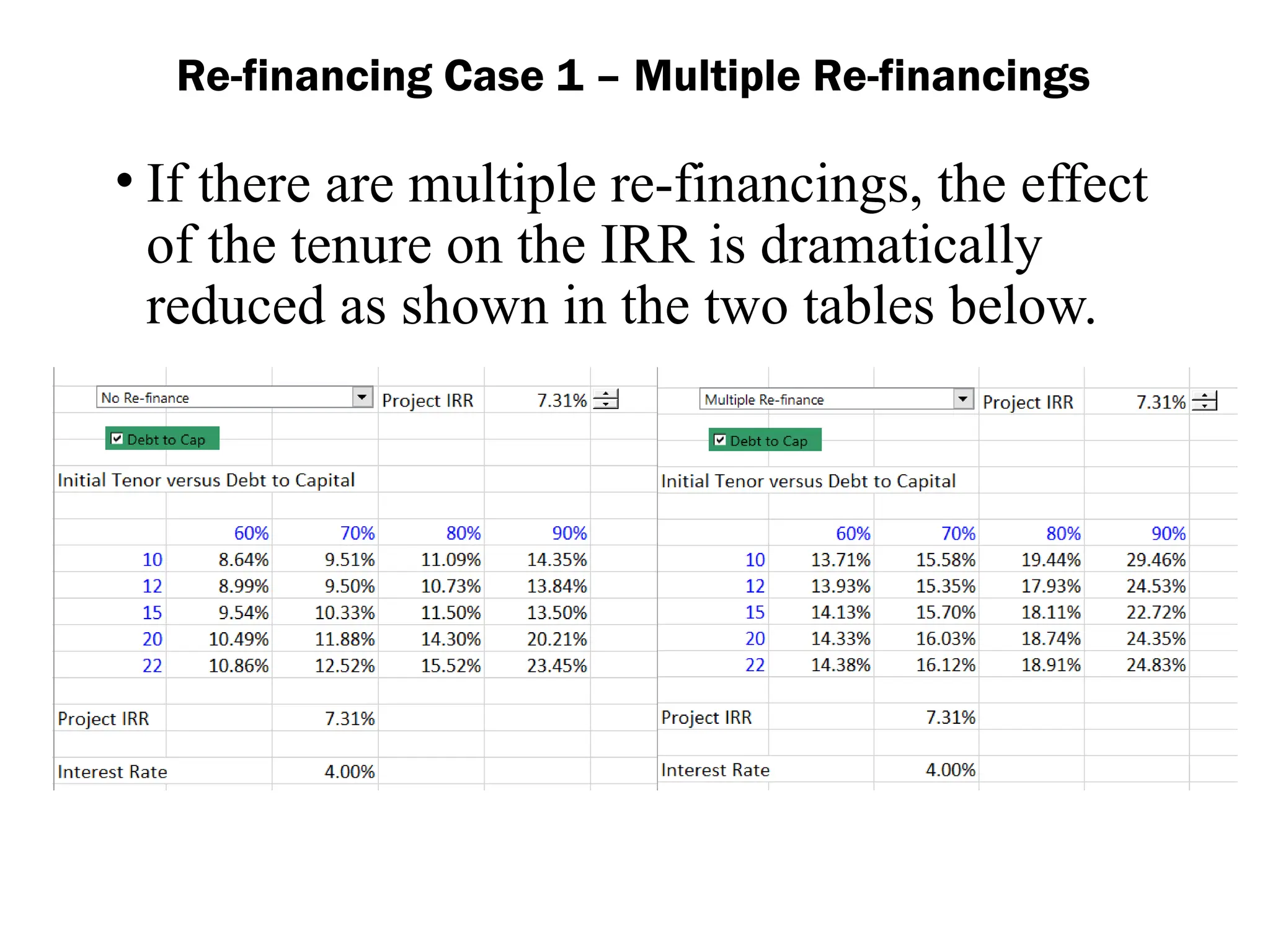

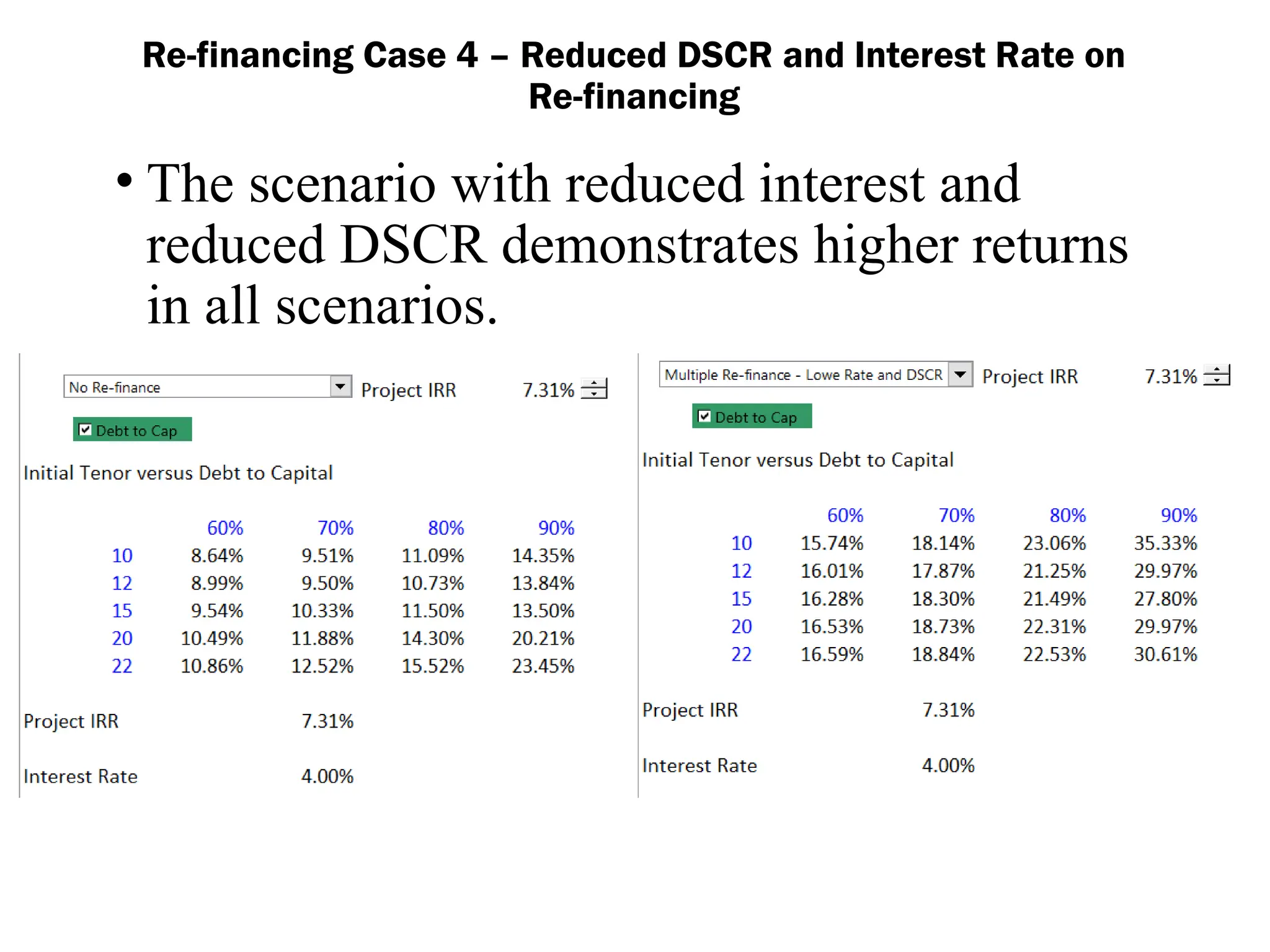

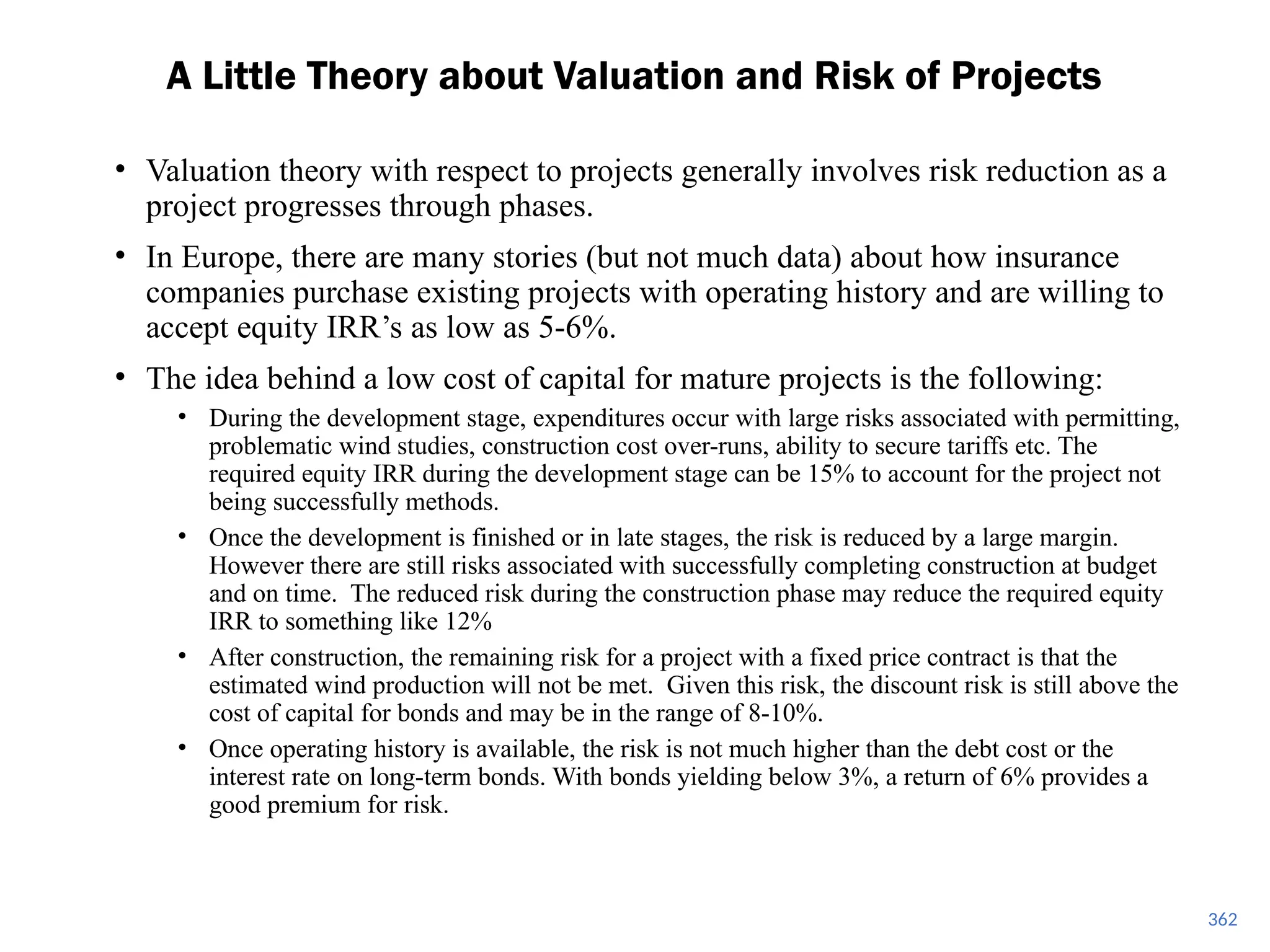

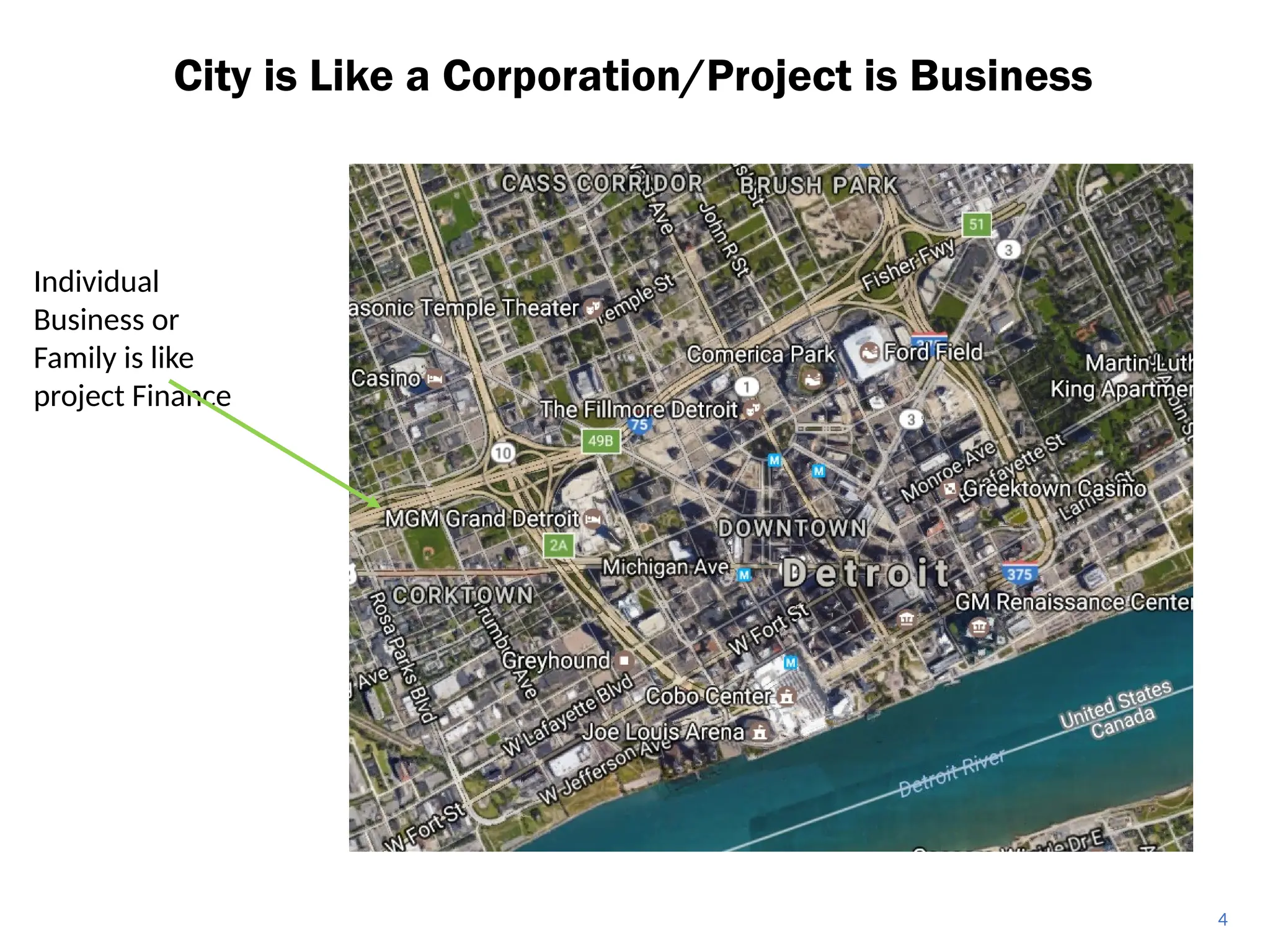

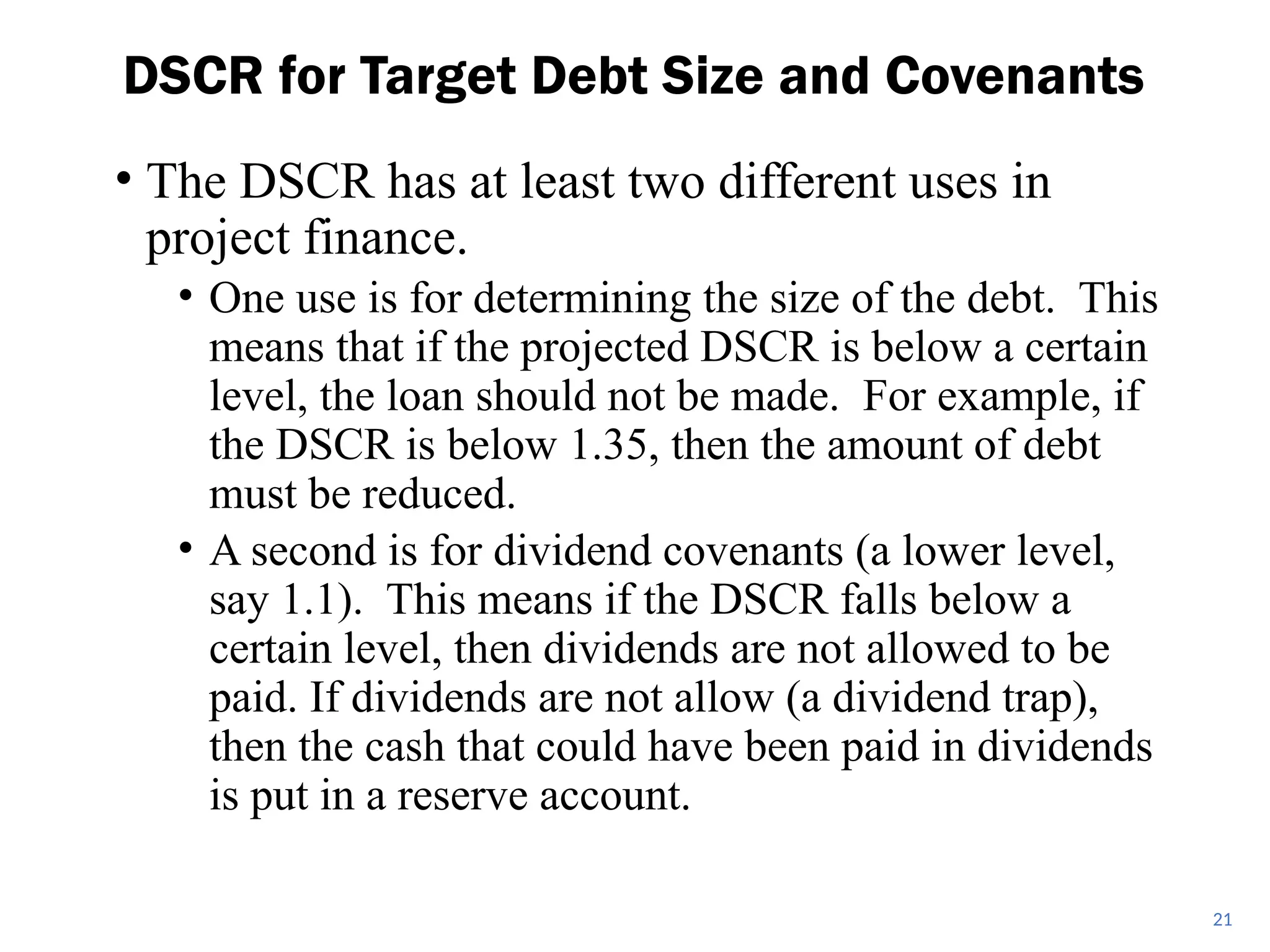

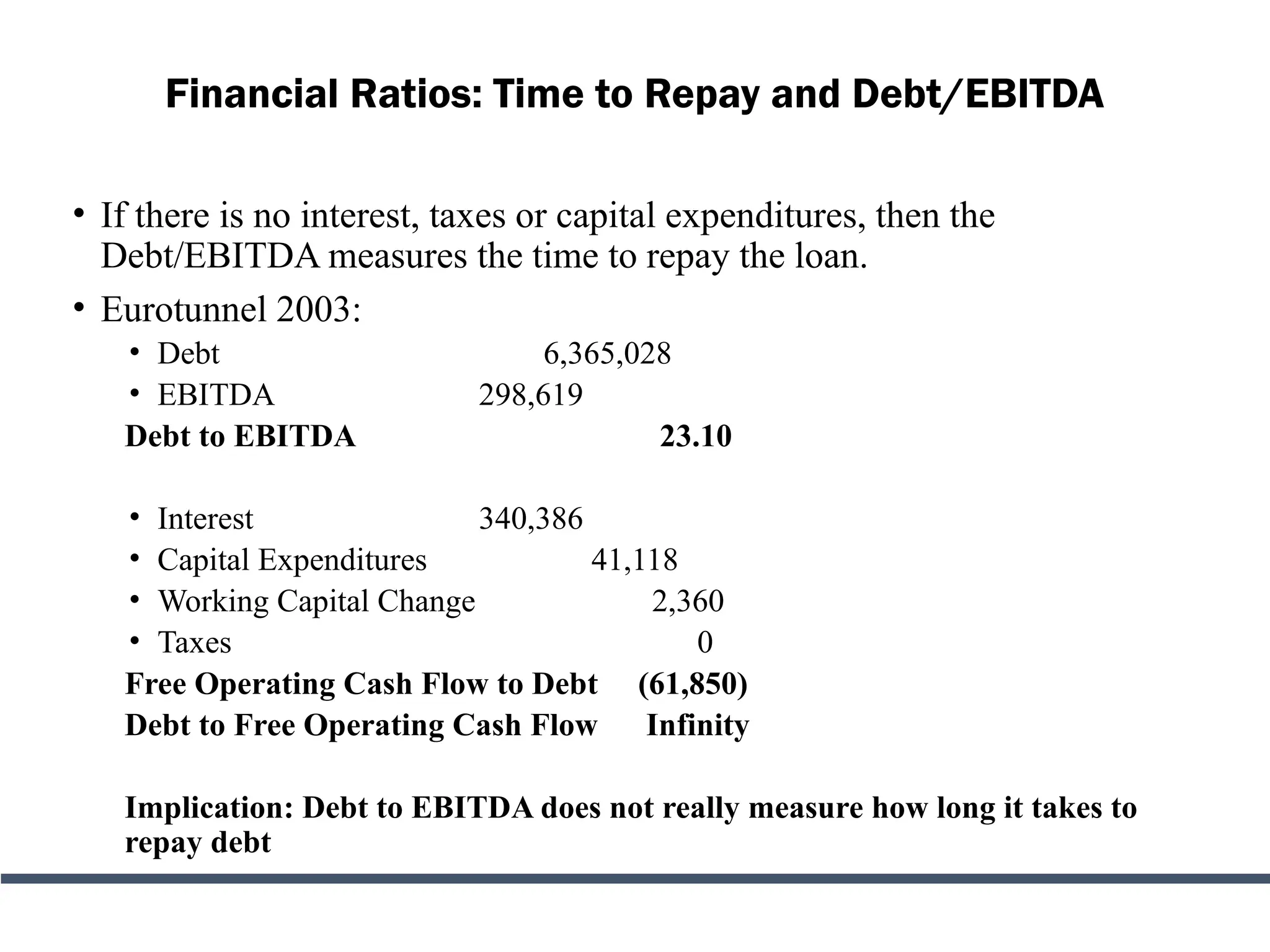

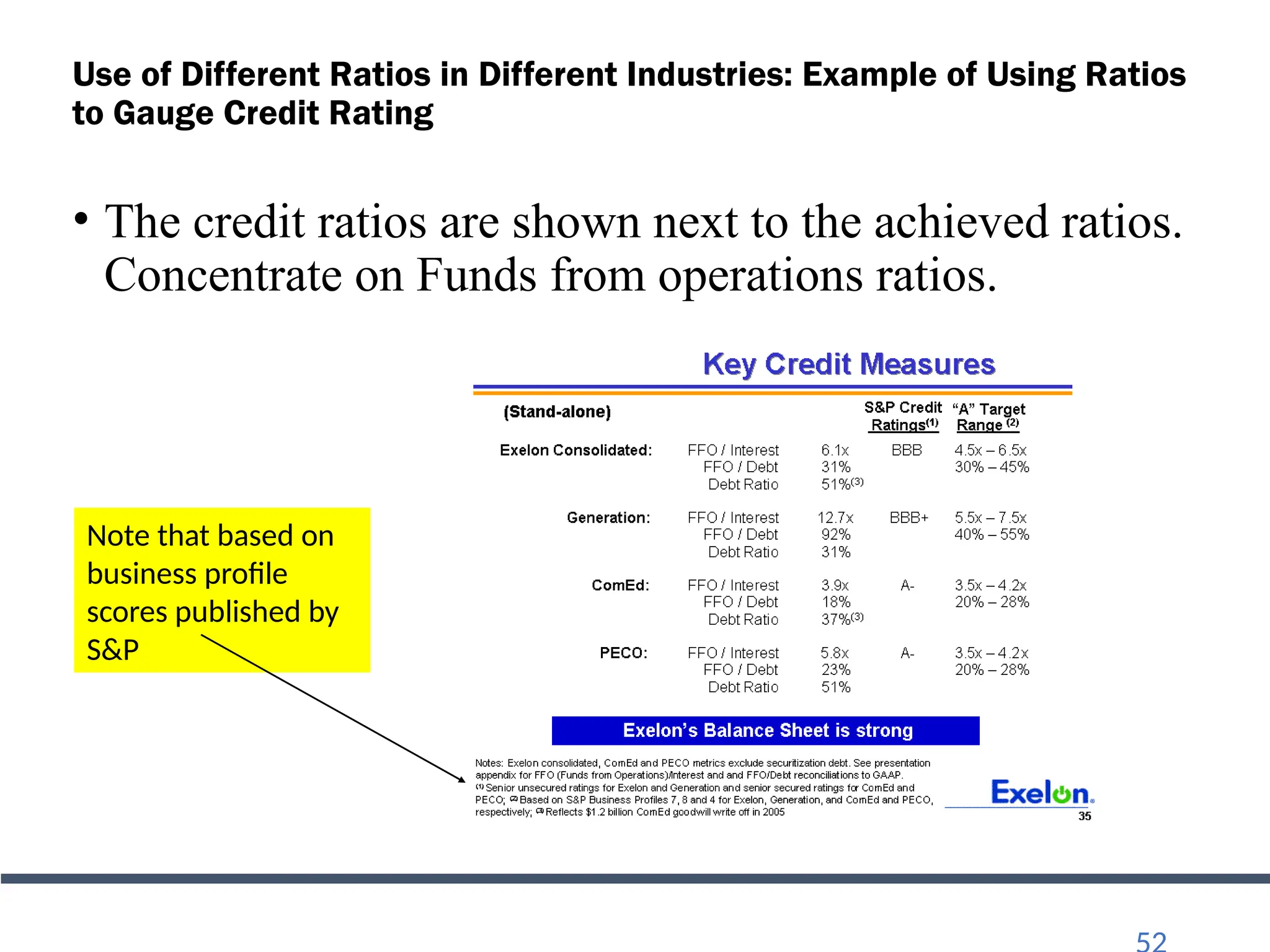

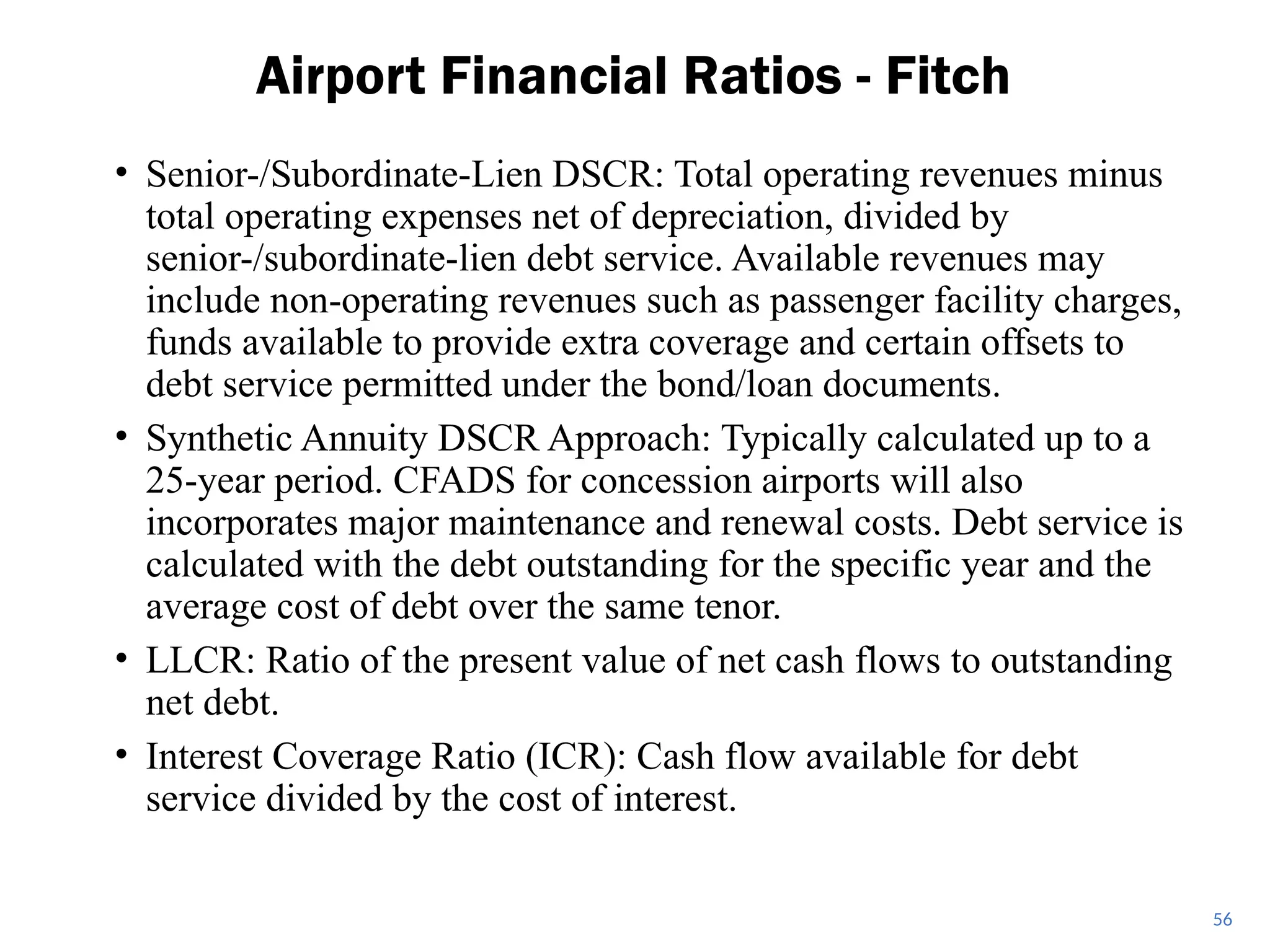

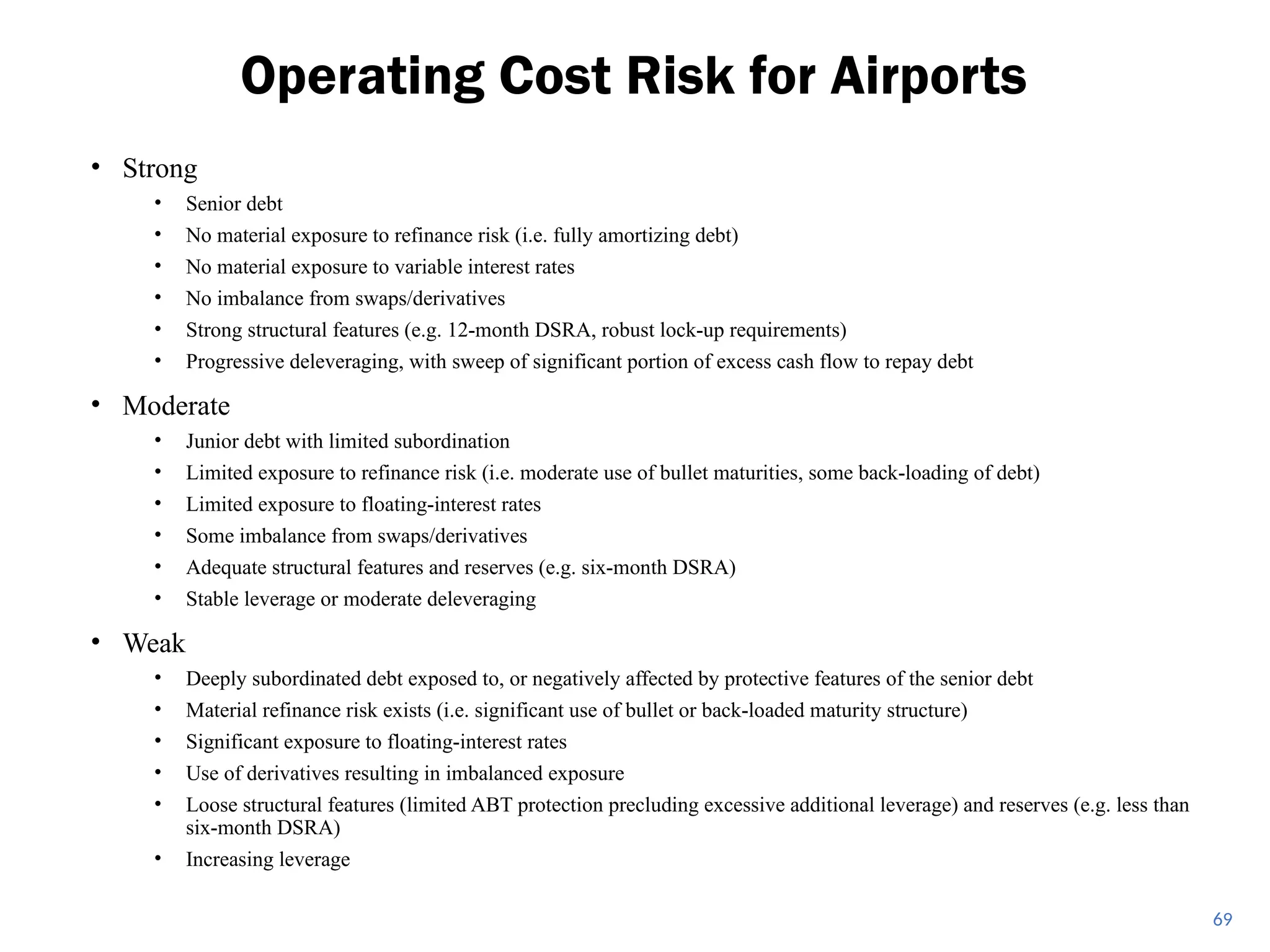

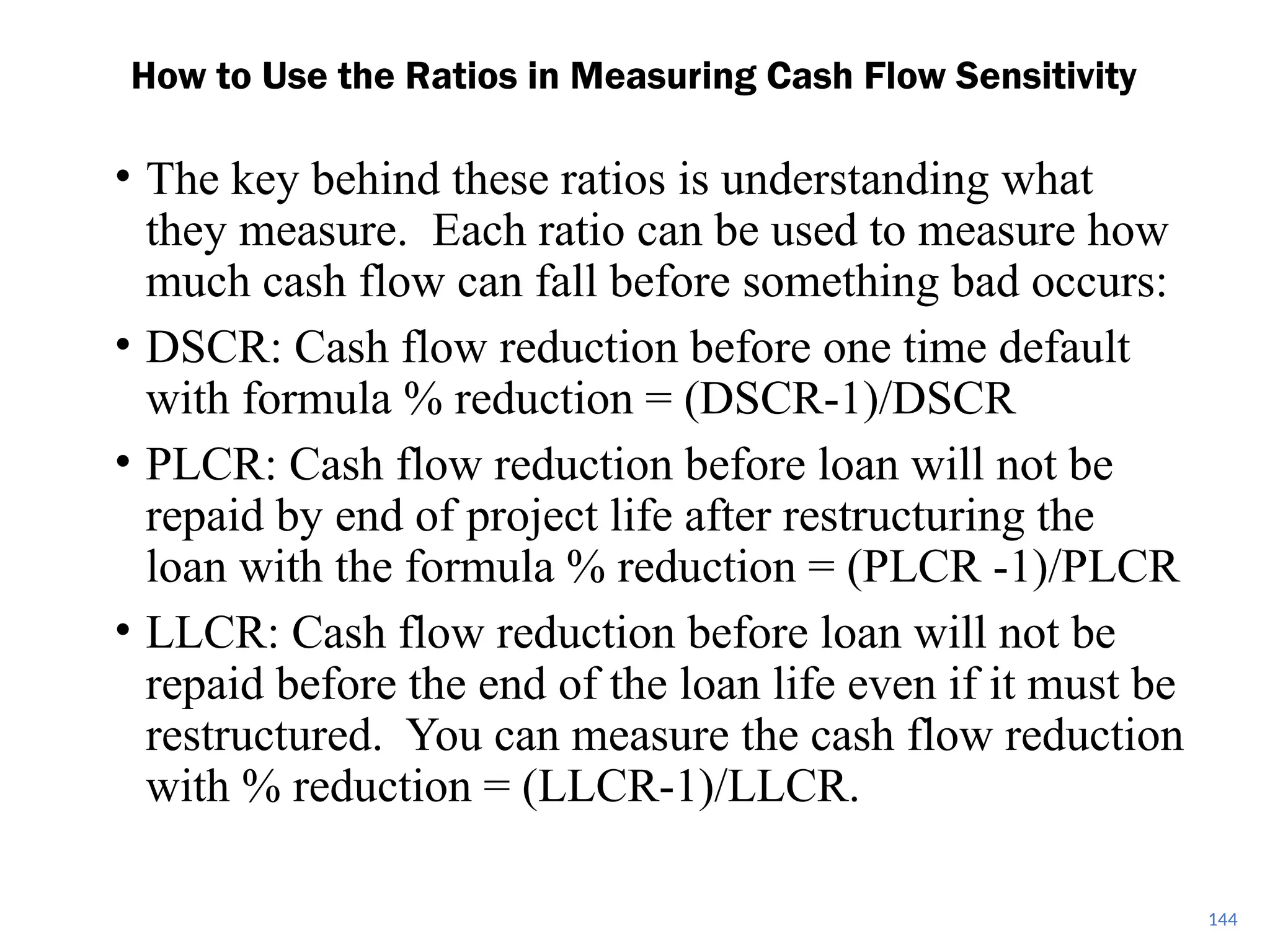

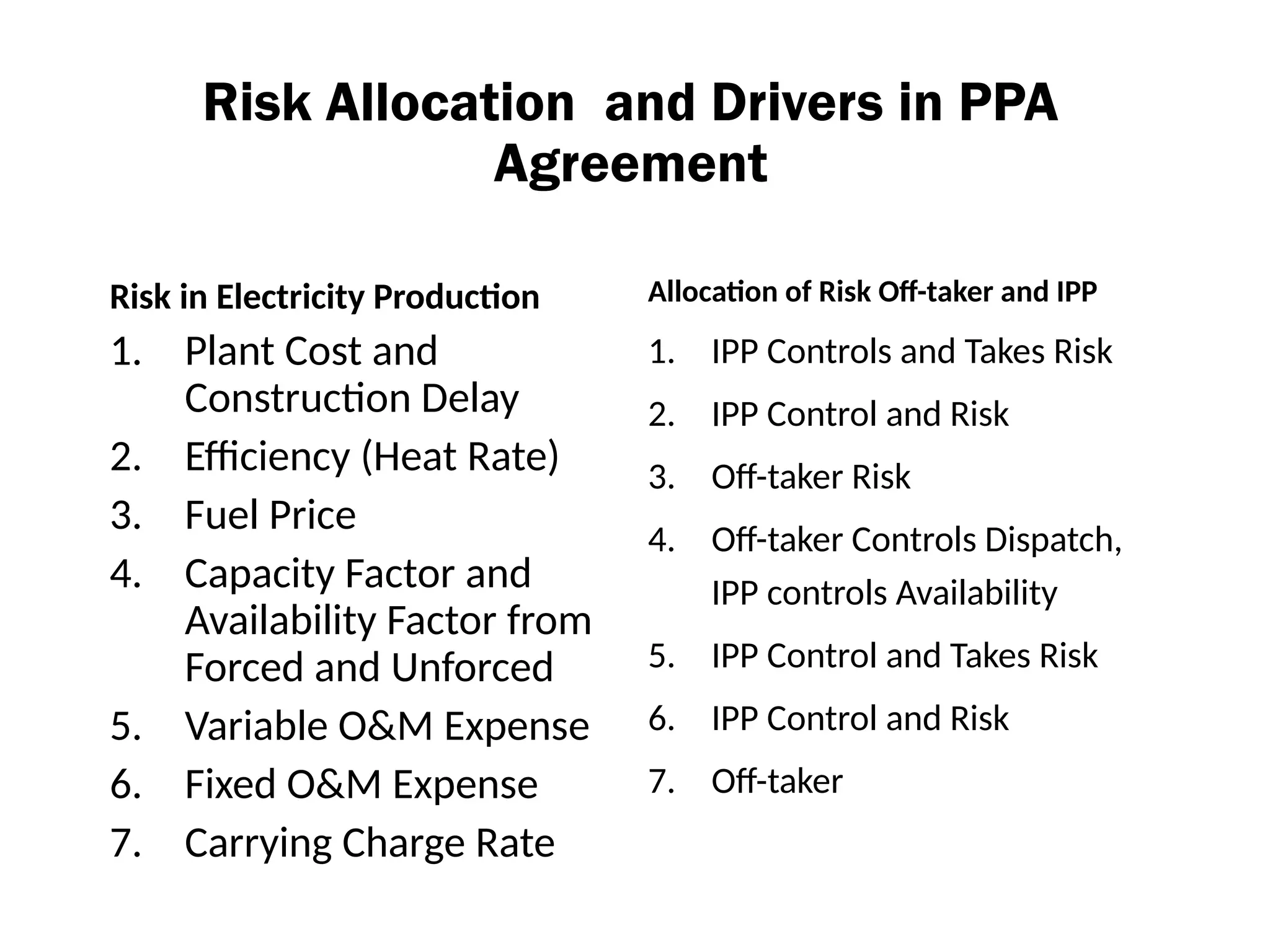

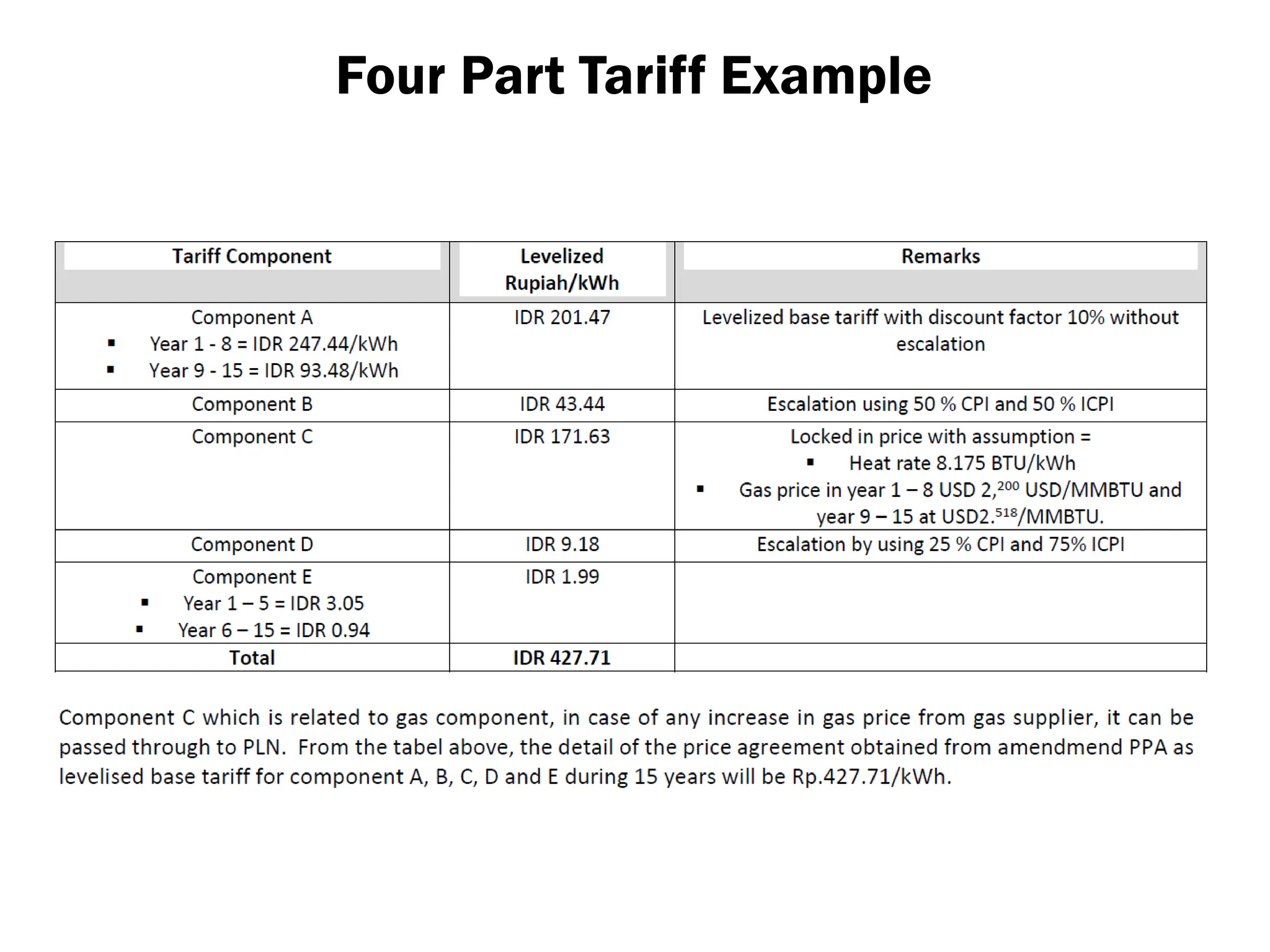

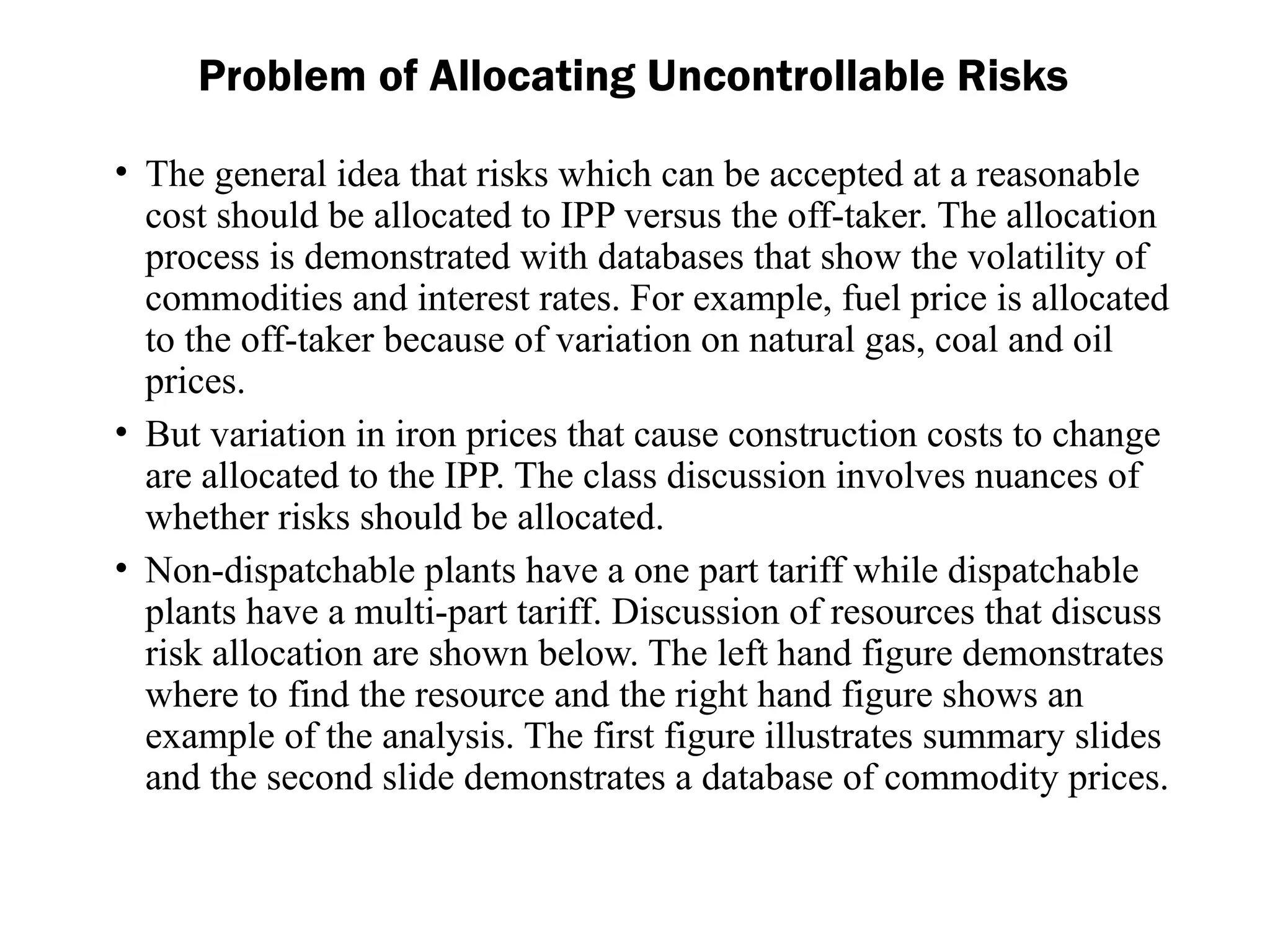

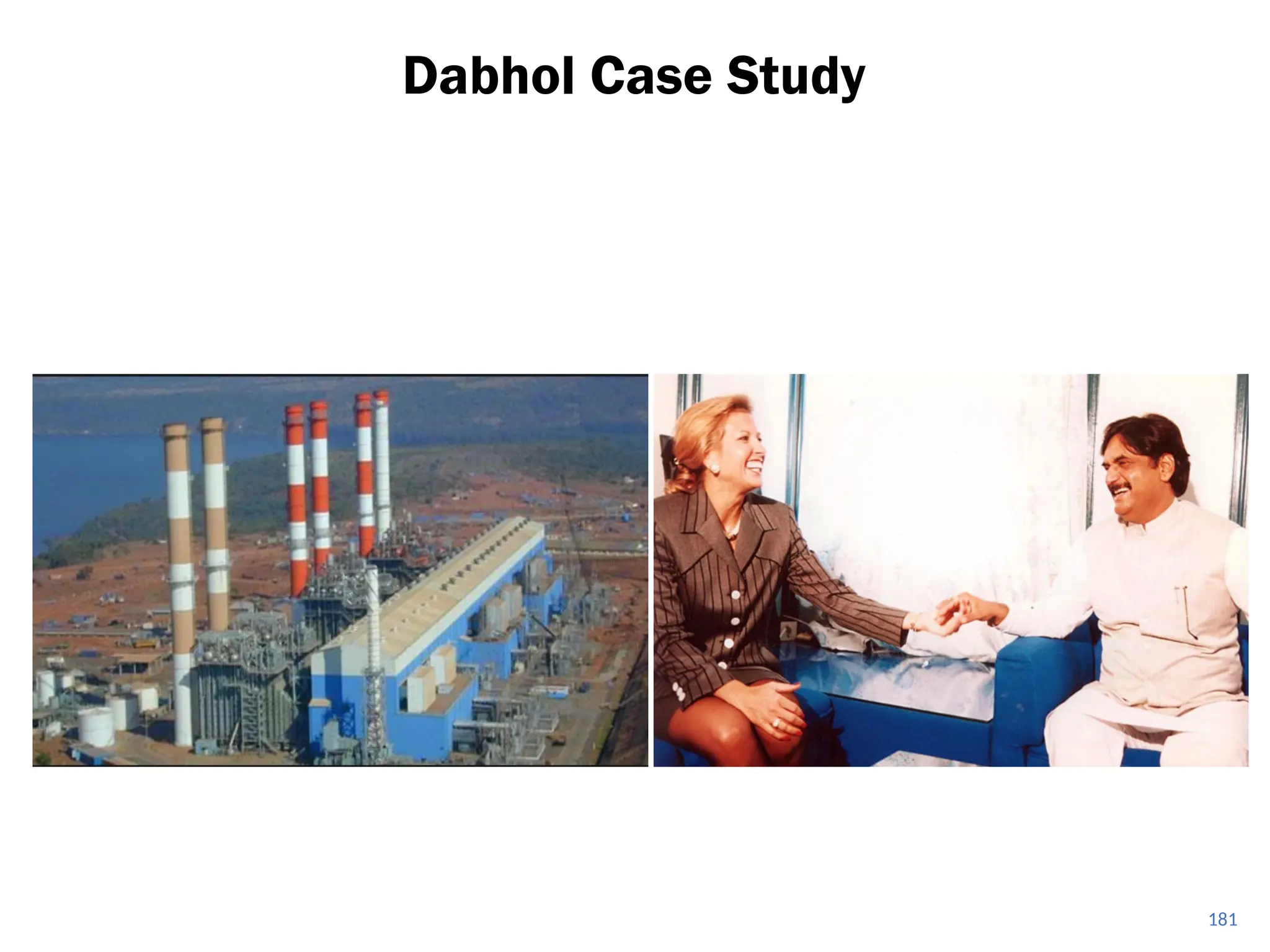

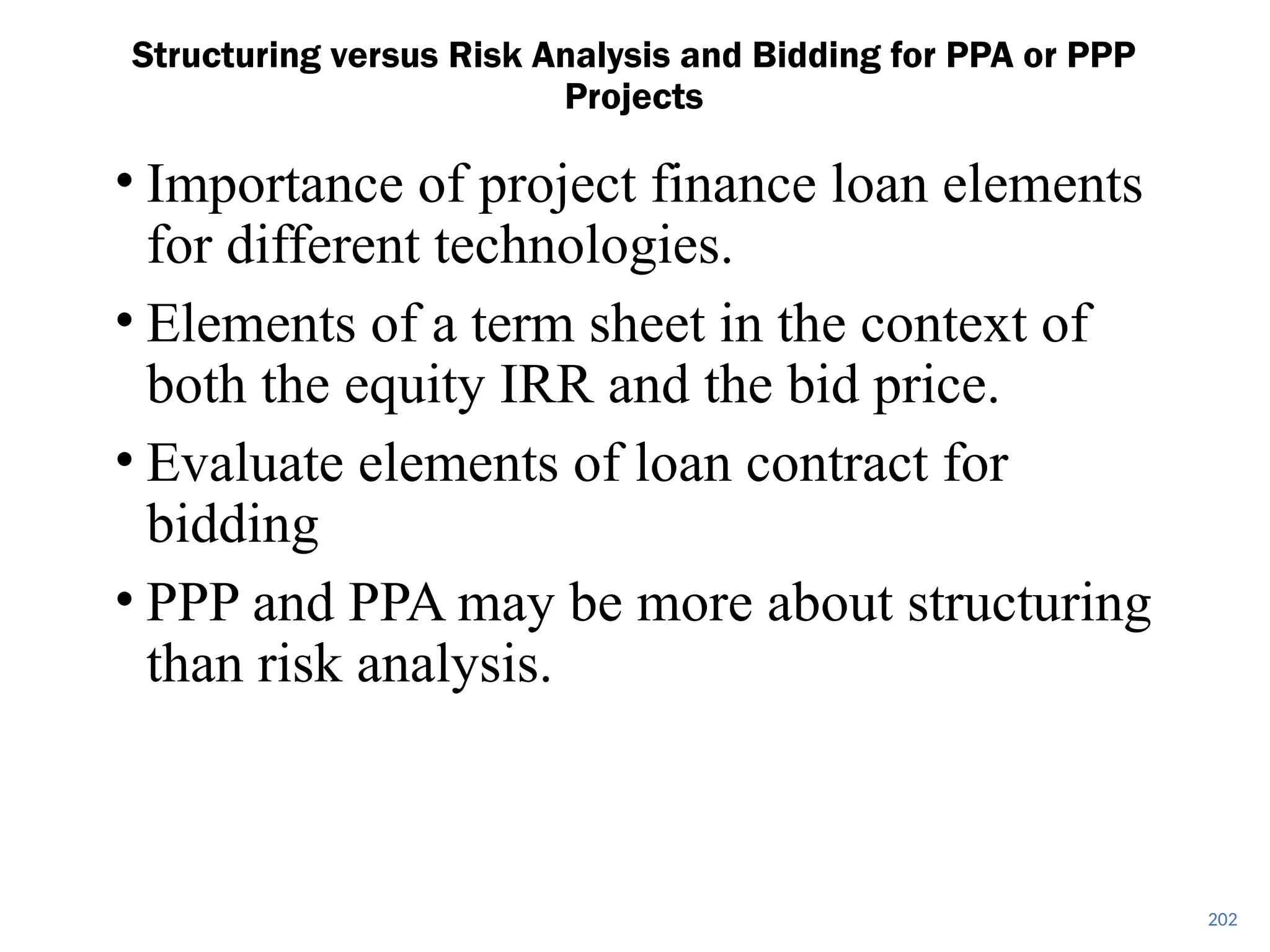

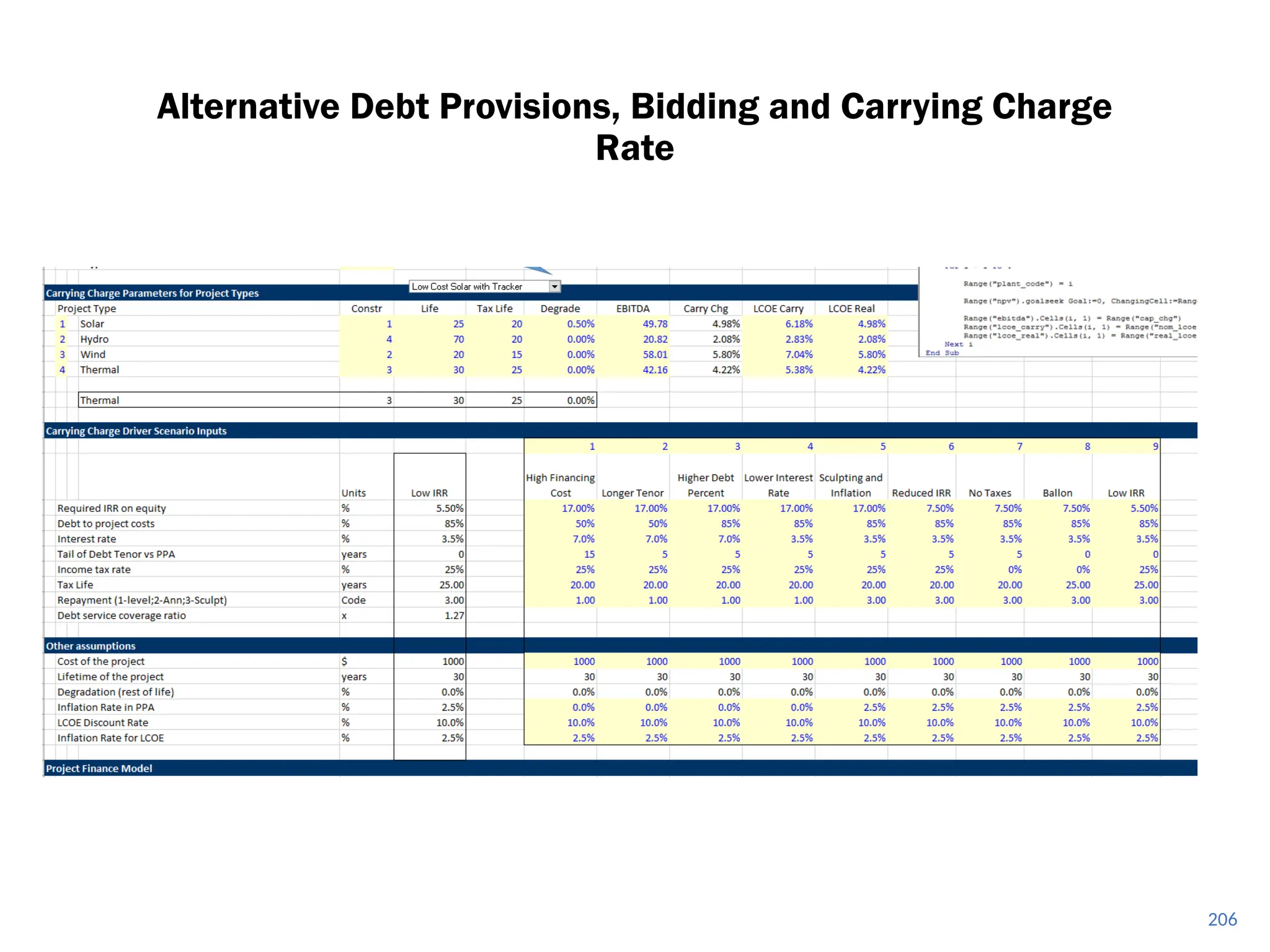

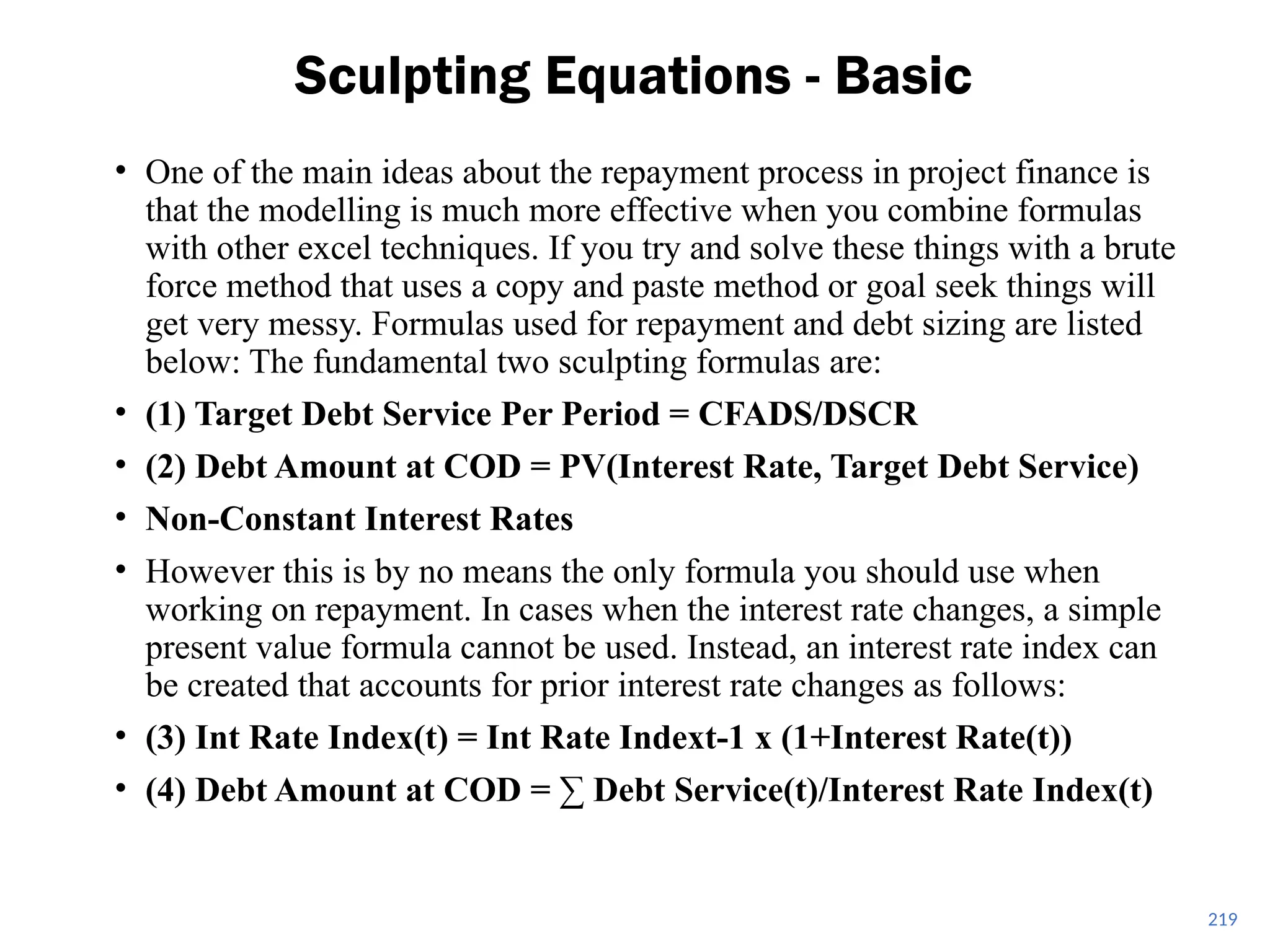

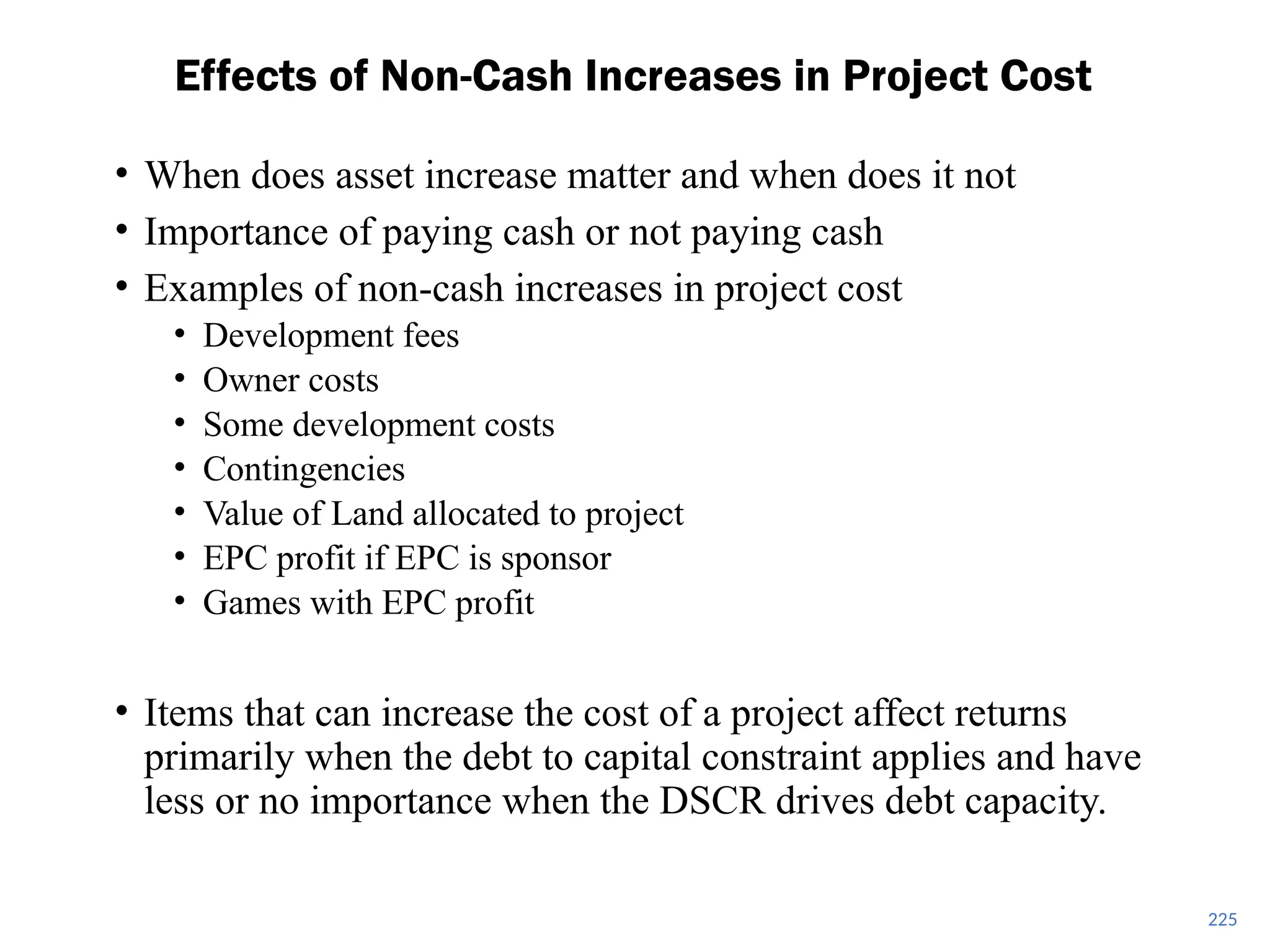

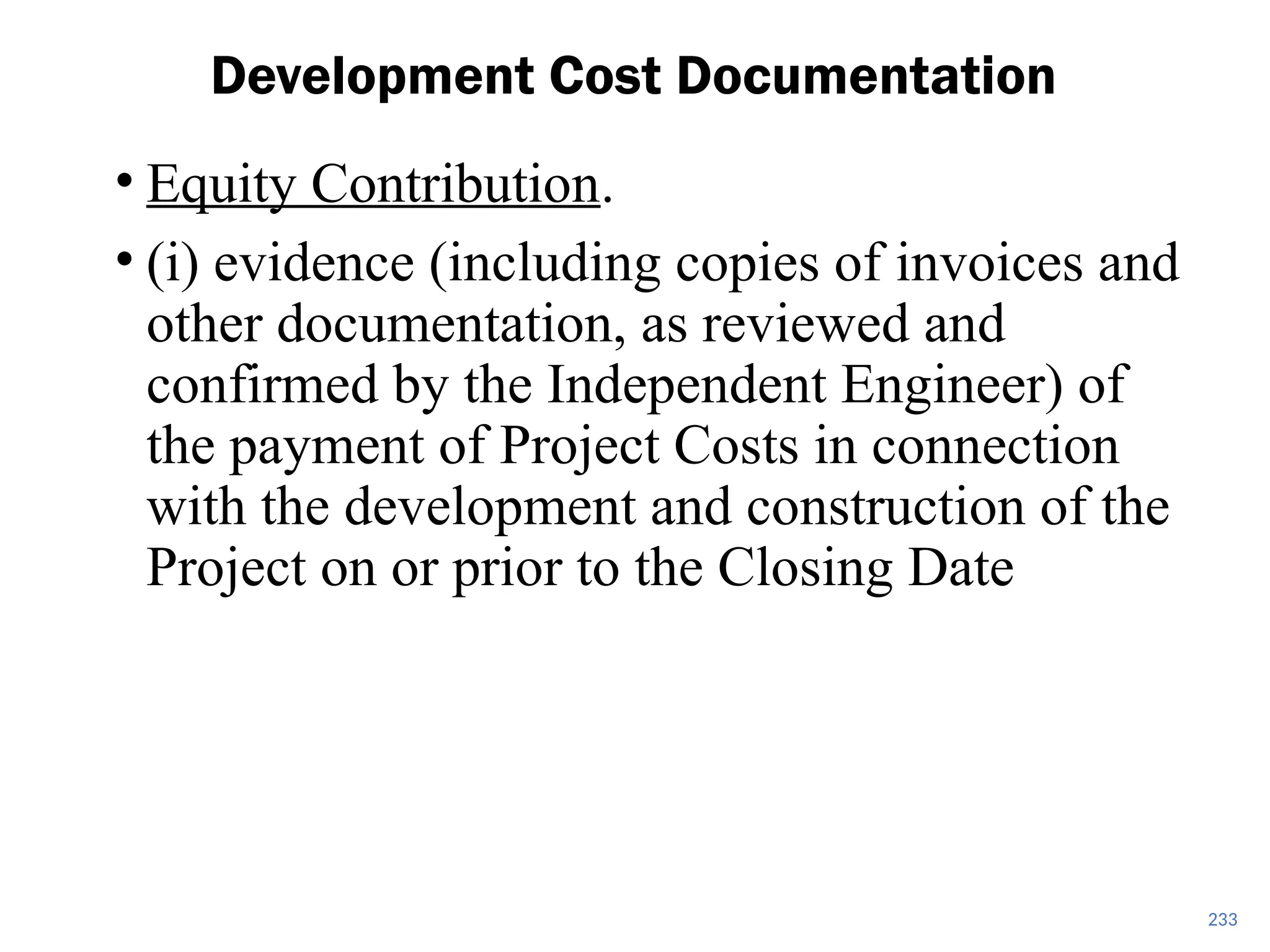

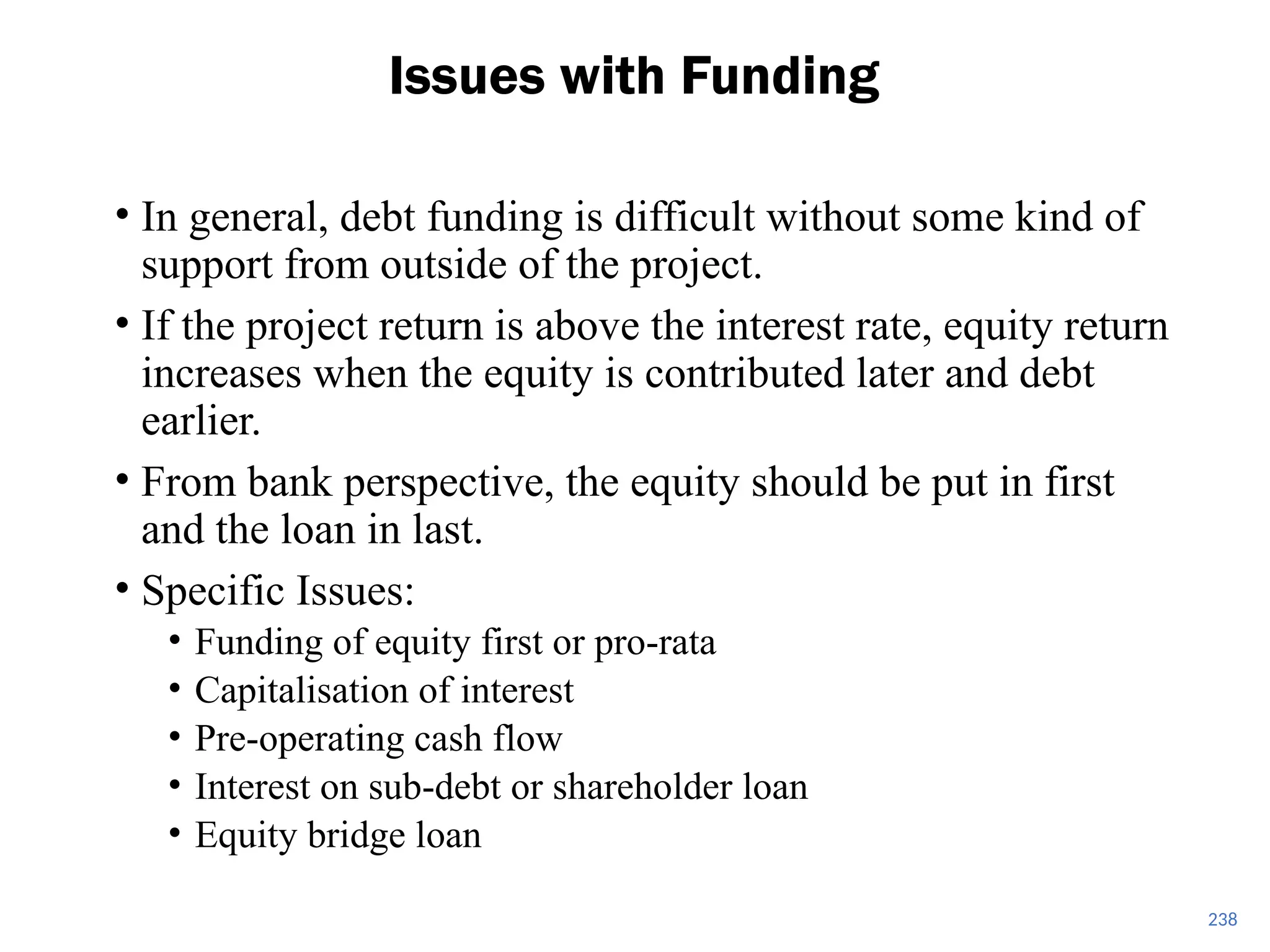

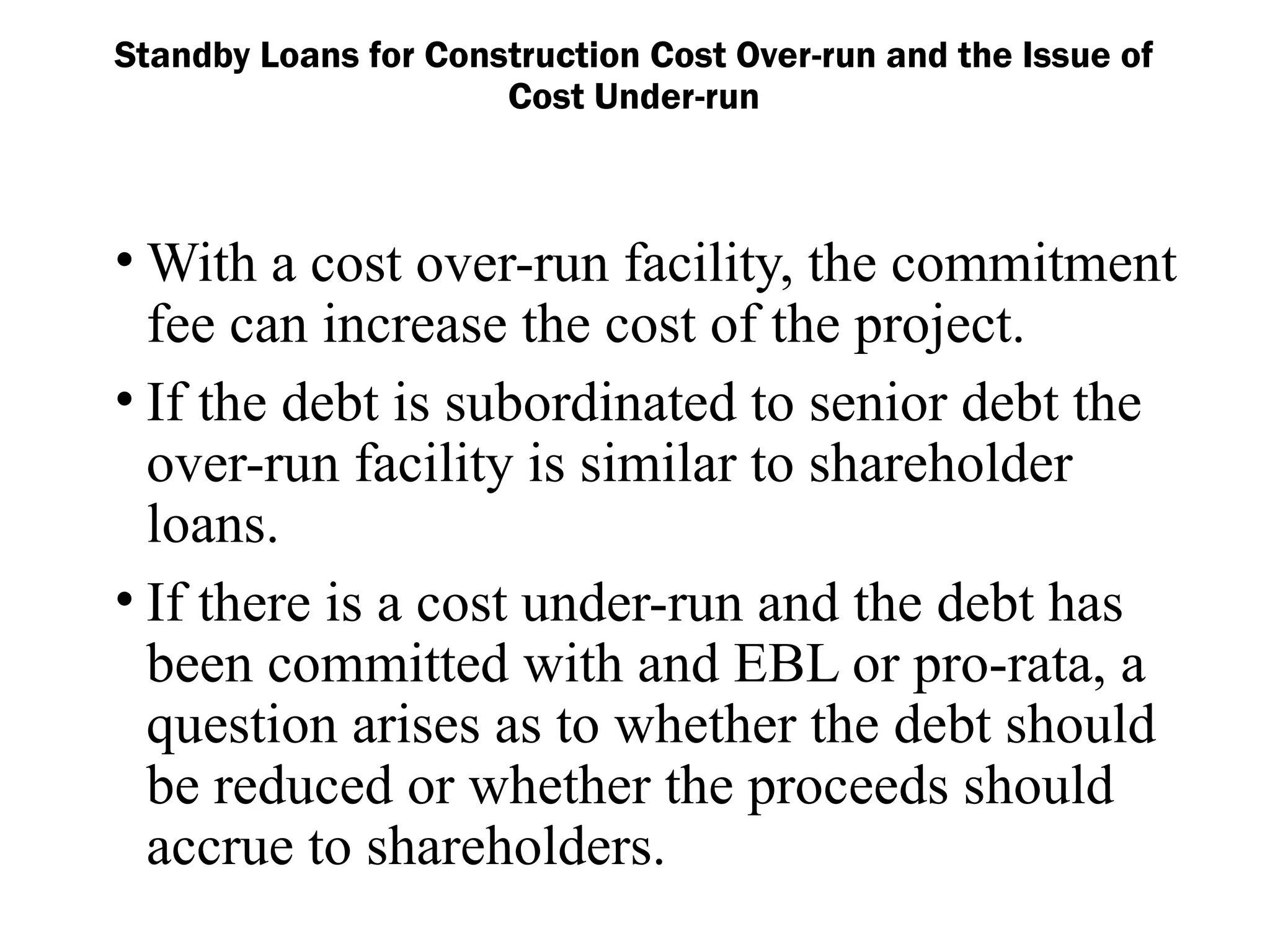

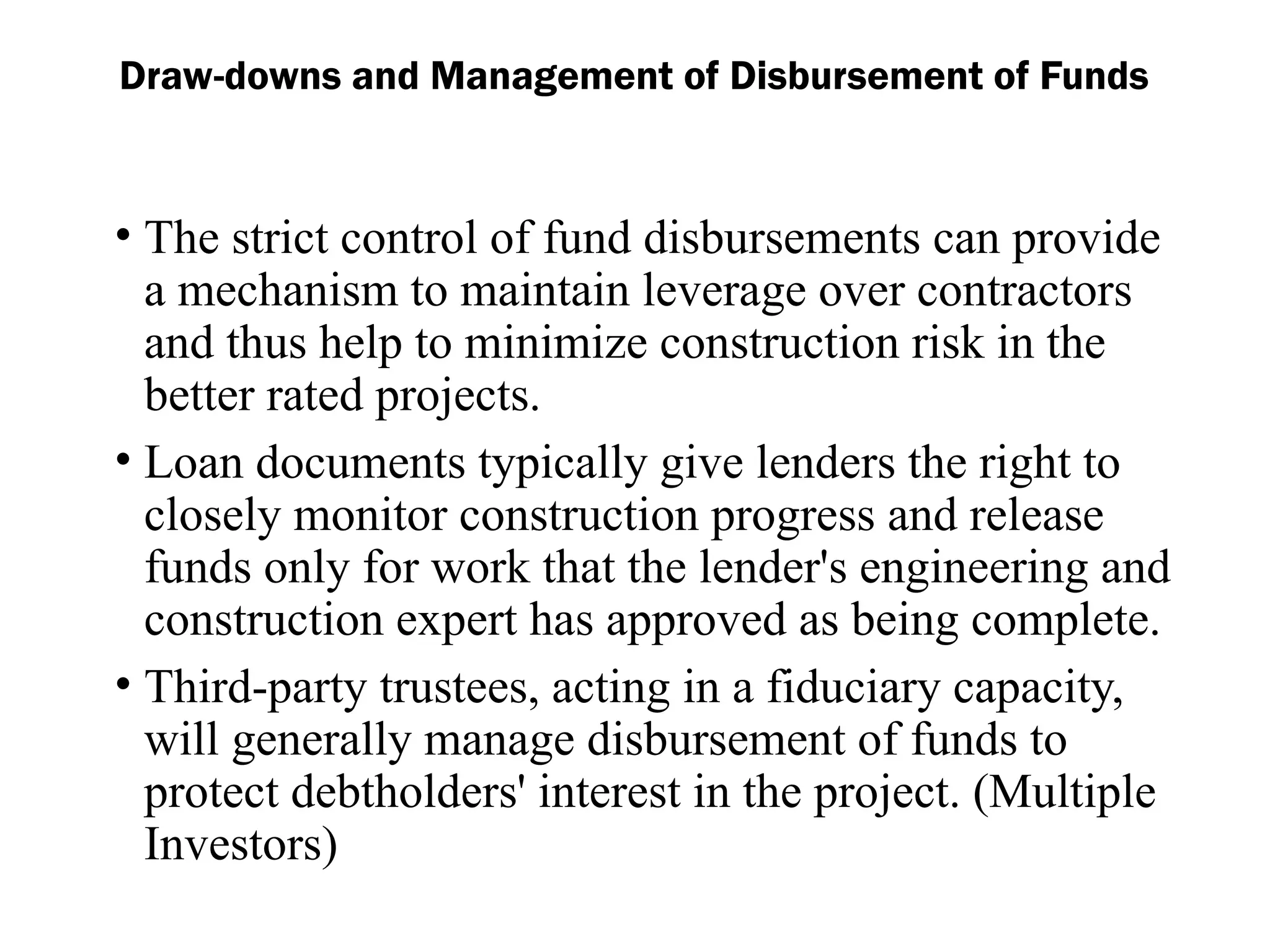

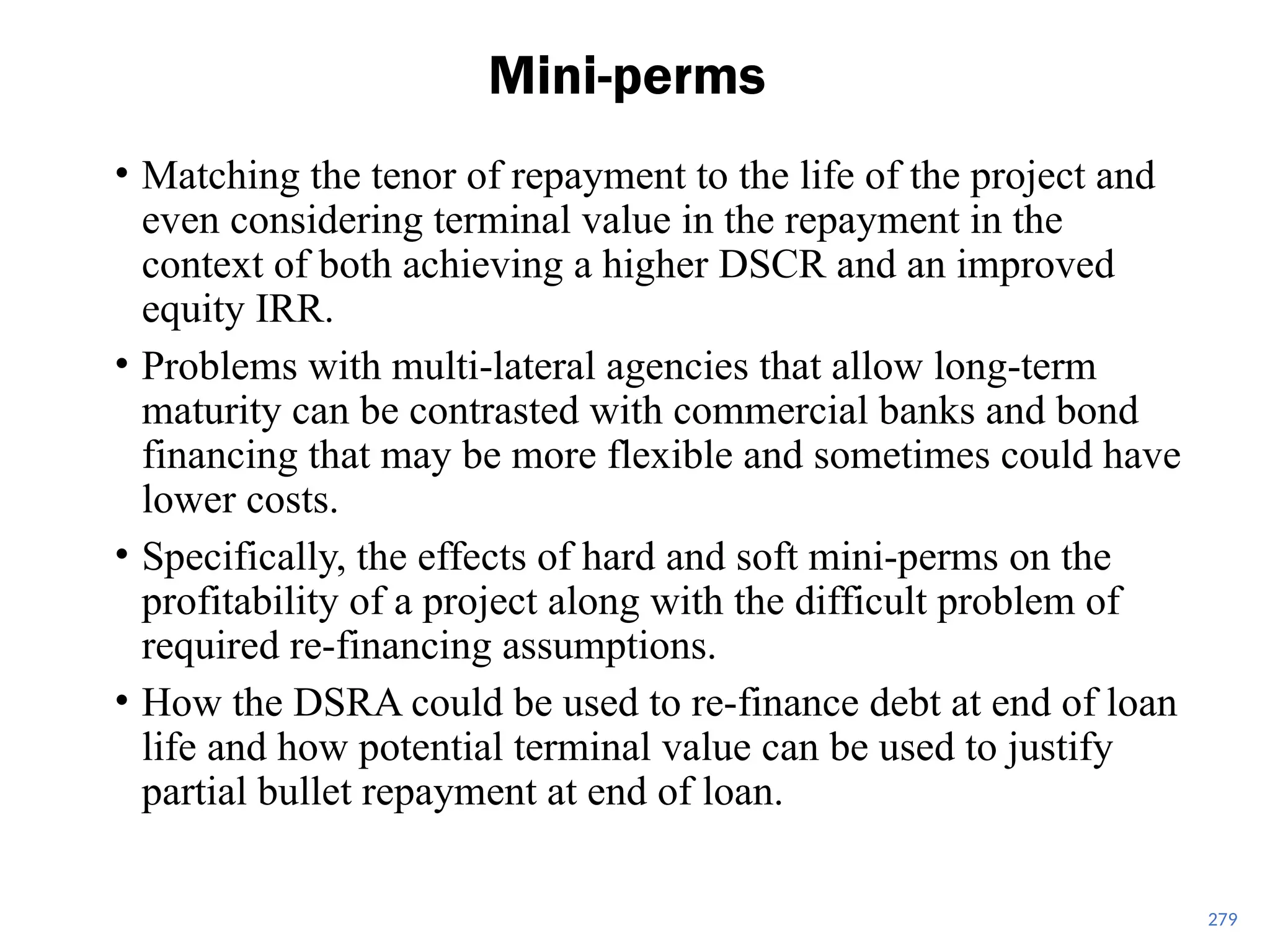

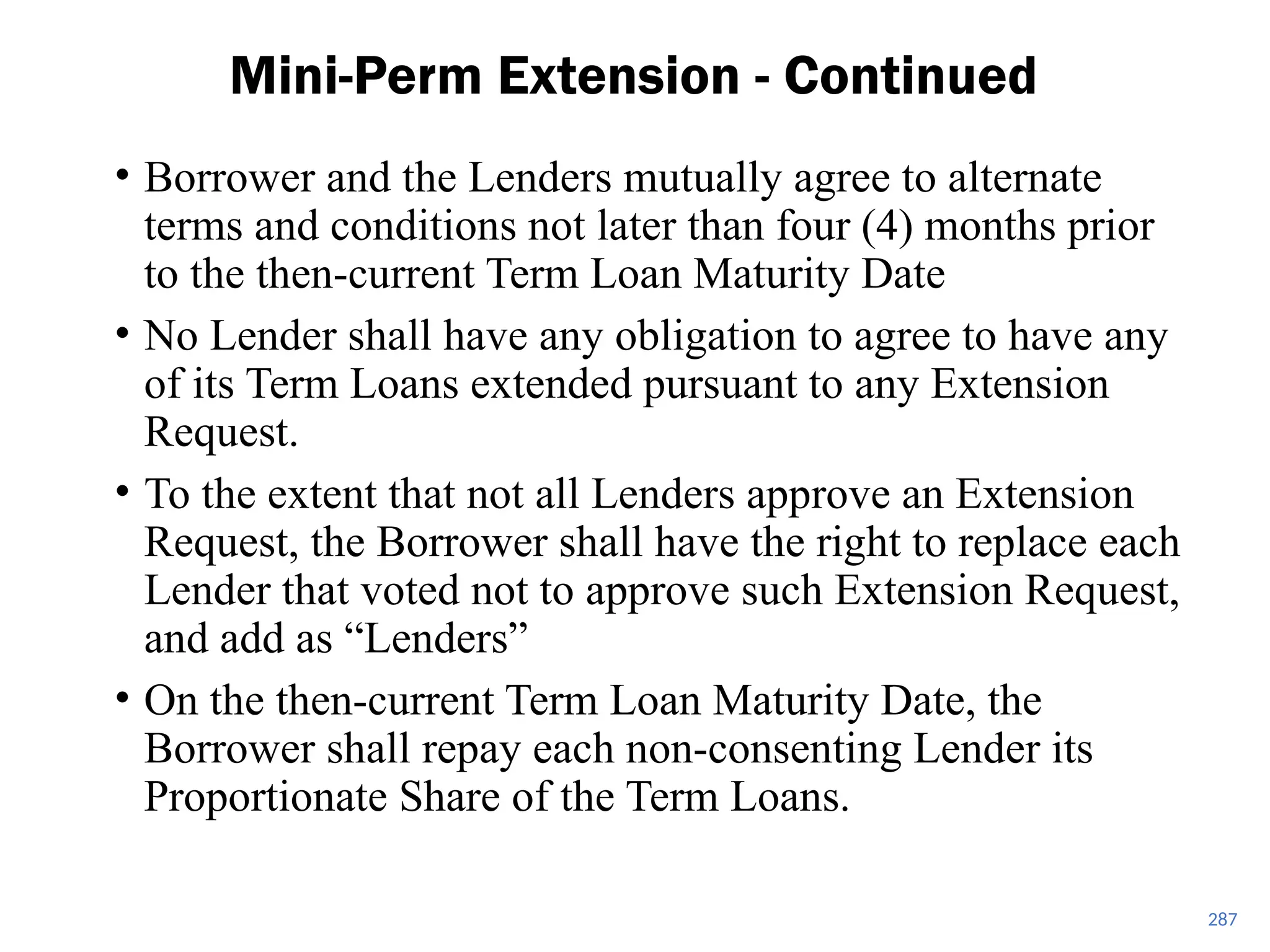

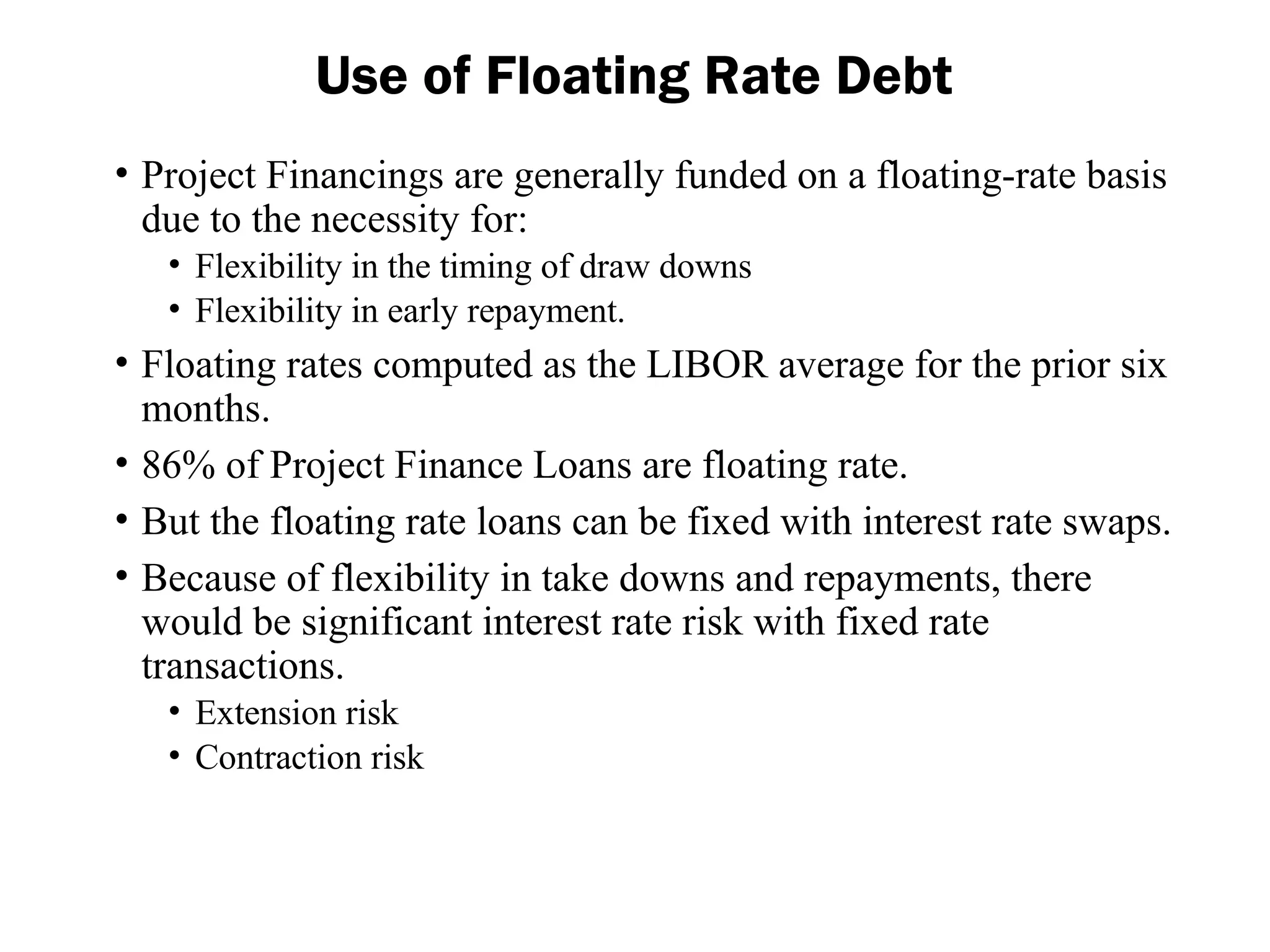

![• Premium for fixing rates is very expensive

because of expected inflation.

Floating versus Fixed Rate Debt

0.00

1.00

2.00

3.00

4.00

5.00

6.00

7.00

01-août-01

01-janv-02

01-juin-02

01-nov-02

01-avr-03

01-sept-03

01-févr-04

01-juil-04

01-déc-04

01-mai-05

01-oct-05

01-mars-06

01-août-06

01-janv-07

01-juin-07

01-nov-07

01-avr-08

01-sept-08

01-févr-09

01-juil-09

01-déc-09

01-mai-10

01-oct-10

01-mars-11

01-août-11

01-janv-12

01-juin-12

01-nov-12

01-avr-13

01-sept-13

01-févr-14

01-juil-14

01-déc-14

01-mai-15

01-oct-15

01-mars-16

01-août-16

01-janv-17

30

YR

Swap

Rate

30 YR Swap Rate [Final Value 2.07 ] vs

Overnight LIBOR [Final Value 0.43 ]

Overnight LIBOR

30 YR Swap Rate](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/project-finance-2-1-250115111236-848ba4b7/75/Project-Finance-2-1-Basics-of-Project-Finance-295-2048.jpg)