This document provides information about a precalculus and trigonometry workbook created by The Great Courses. It includes a biography of the workbook's author, Professor Bruce H. Edwards of the University of Florida. The workbook is designed to accompany Professor Edwards' Great Courses lecture series on precalculus and contains 30 lesson guides on topics ranging from functions and complex numbers to trigonometric identities, vectors, and conic sections. It is published by The Great Courses, an educational media company located in Chantilly, Virginia.

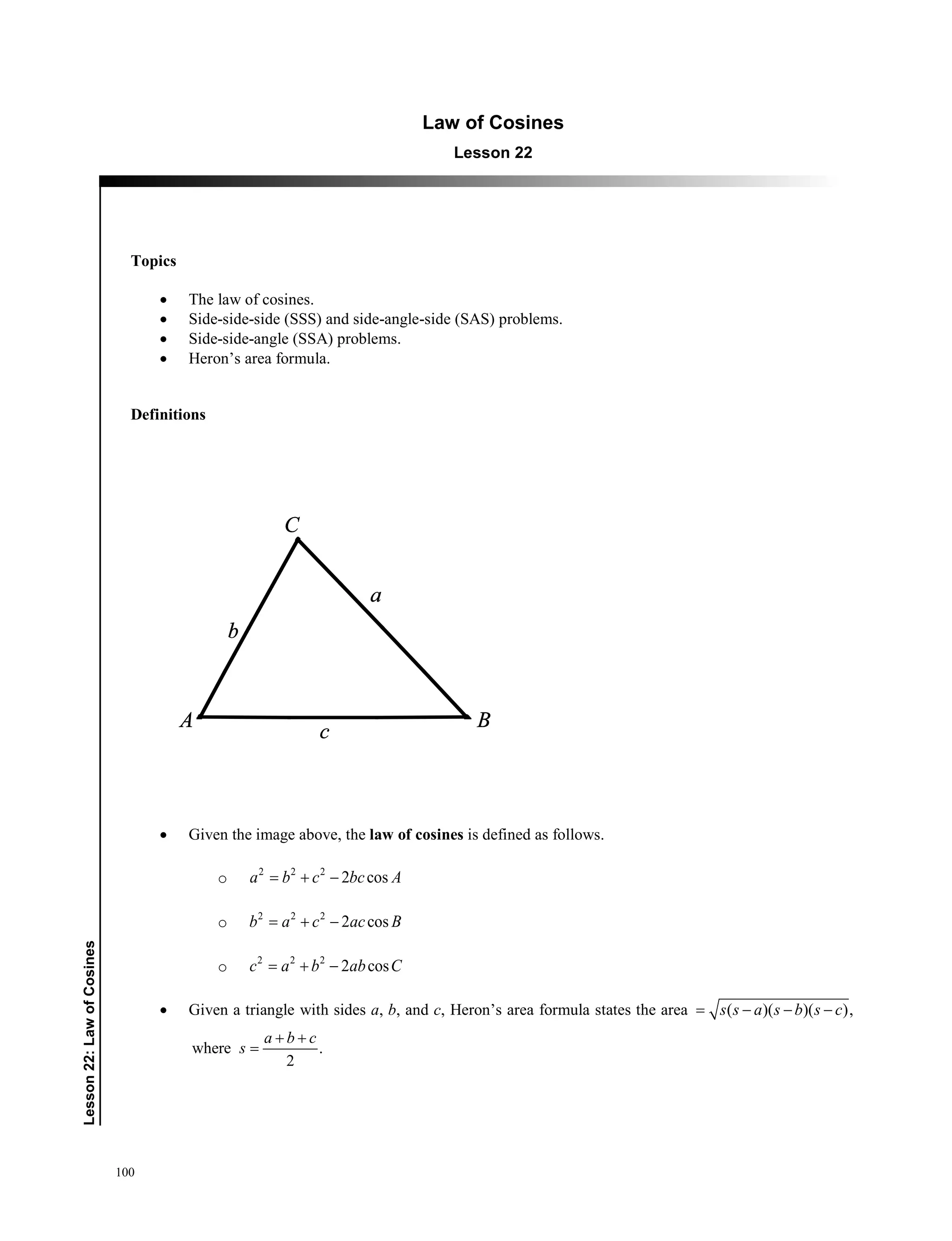

![THE GREAT COURSES®

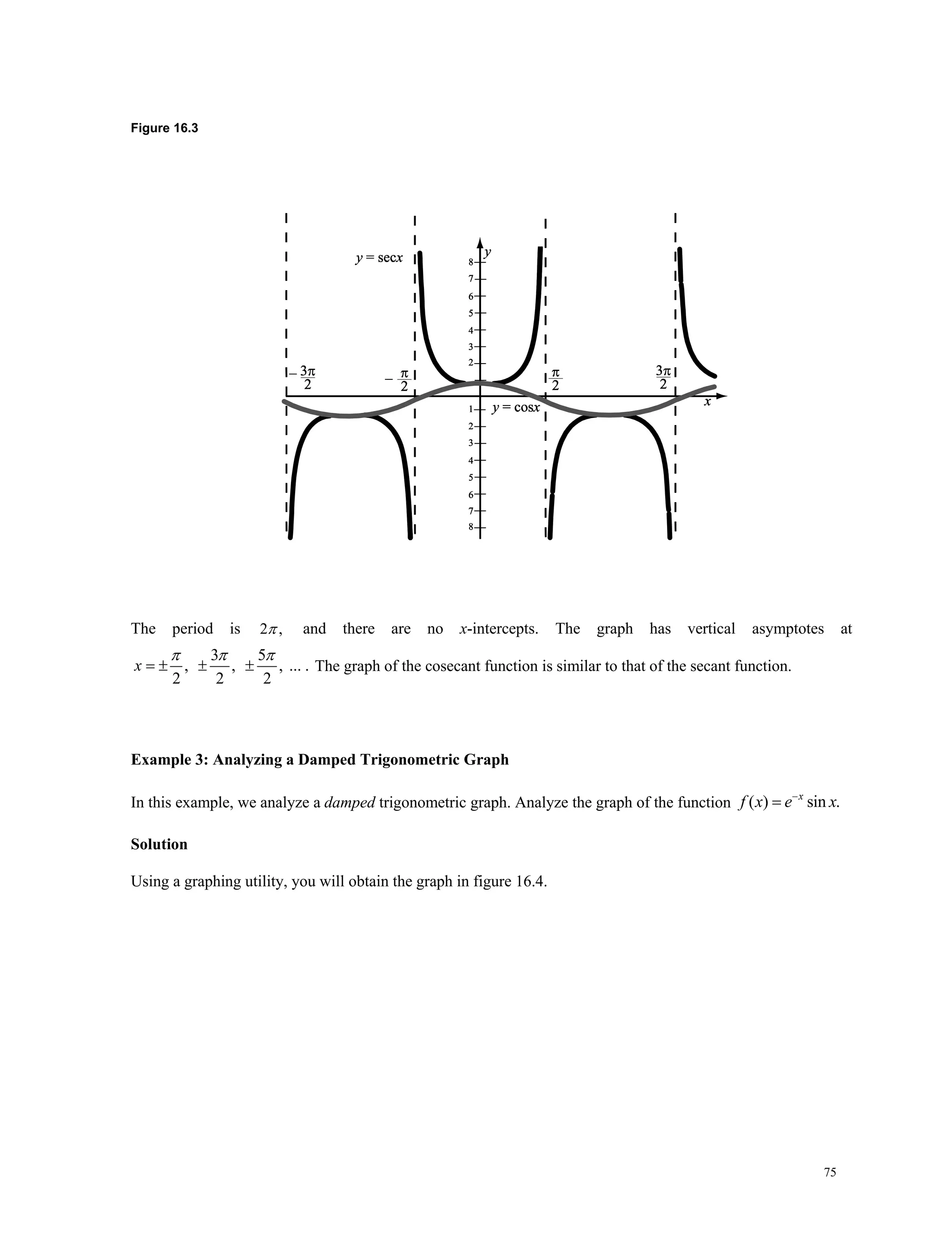

Corporate Headquarters

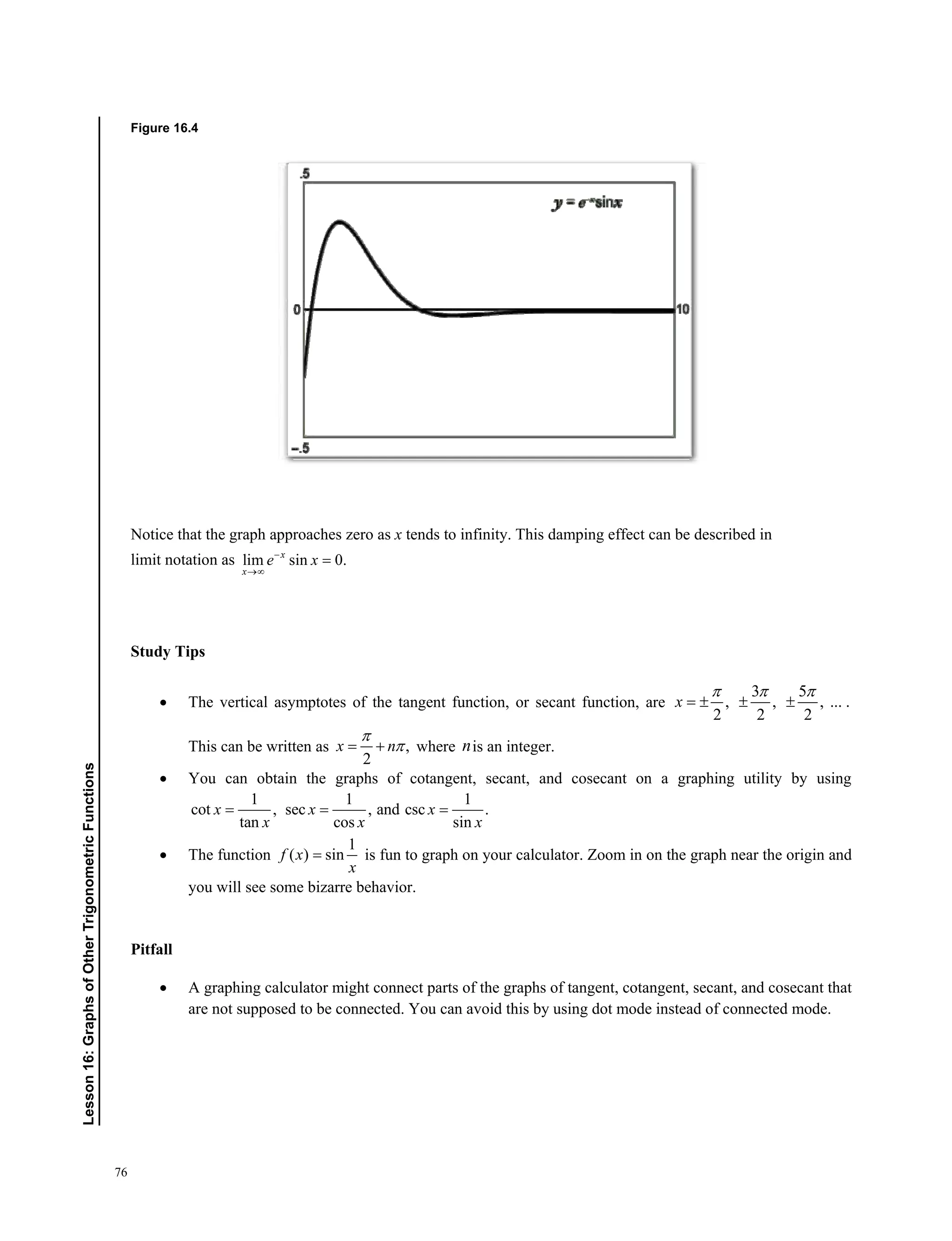

4840 Westfields Boulevard, Suite 500

Chantilly, VA 20151-2299

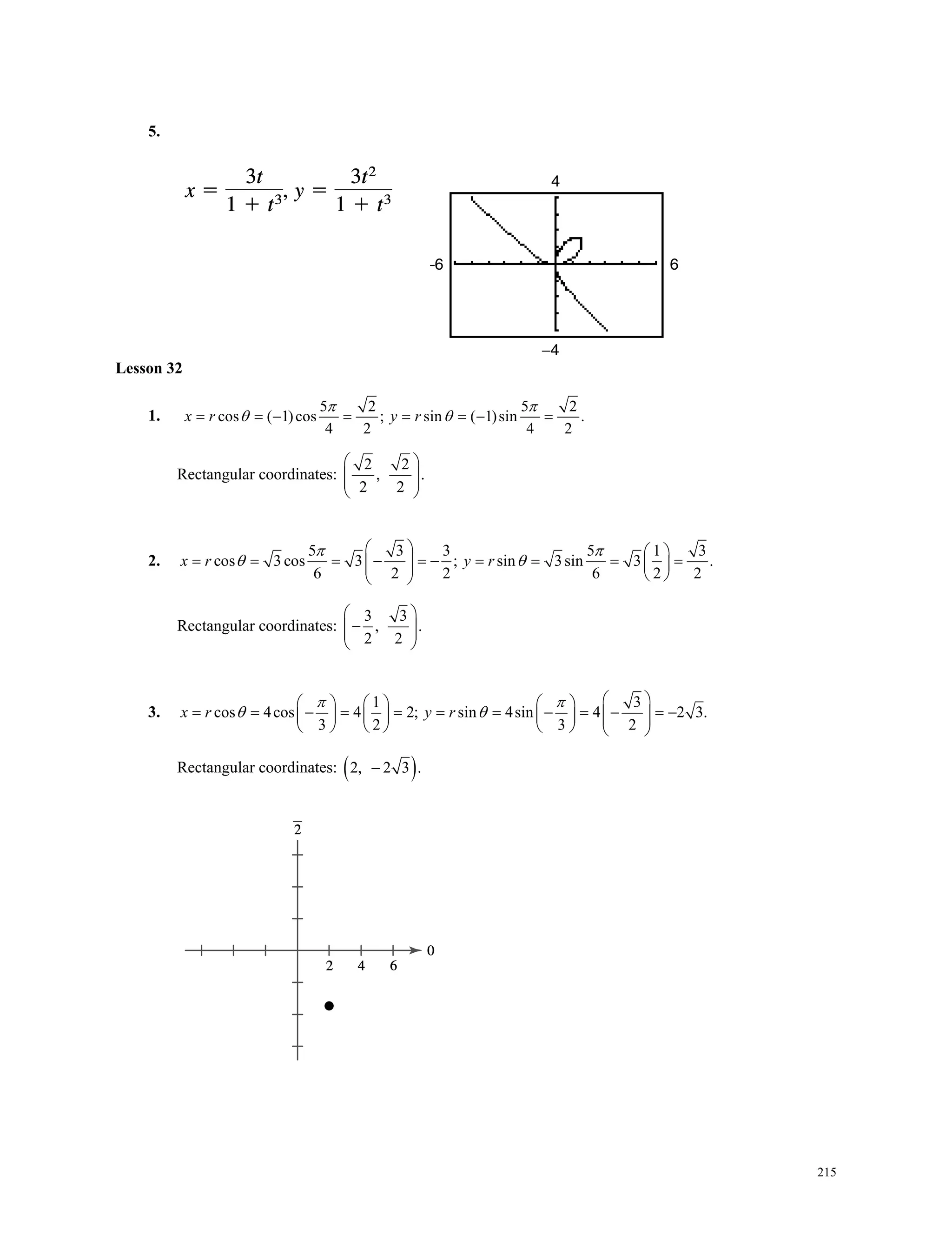

USA

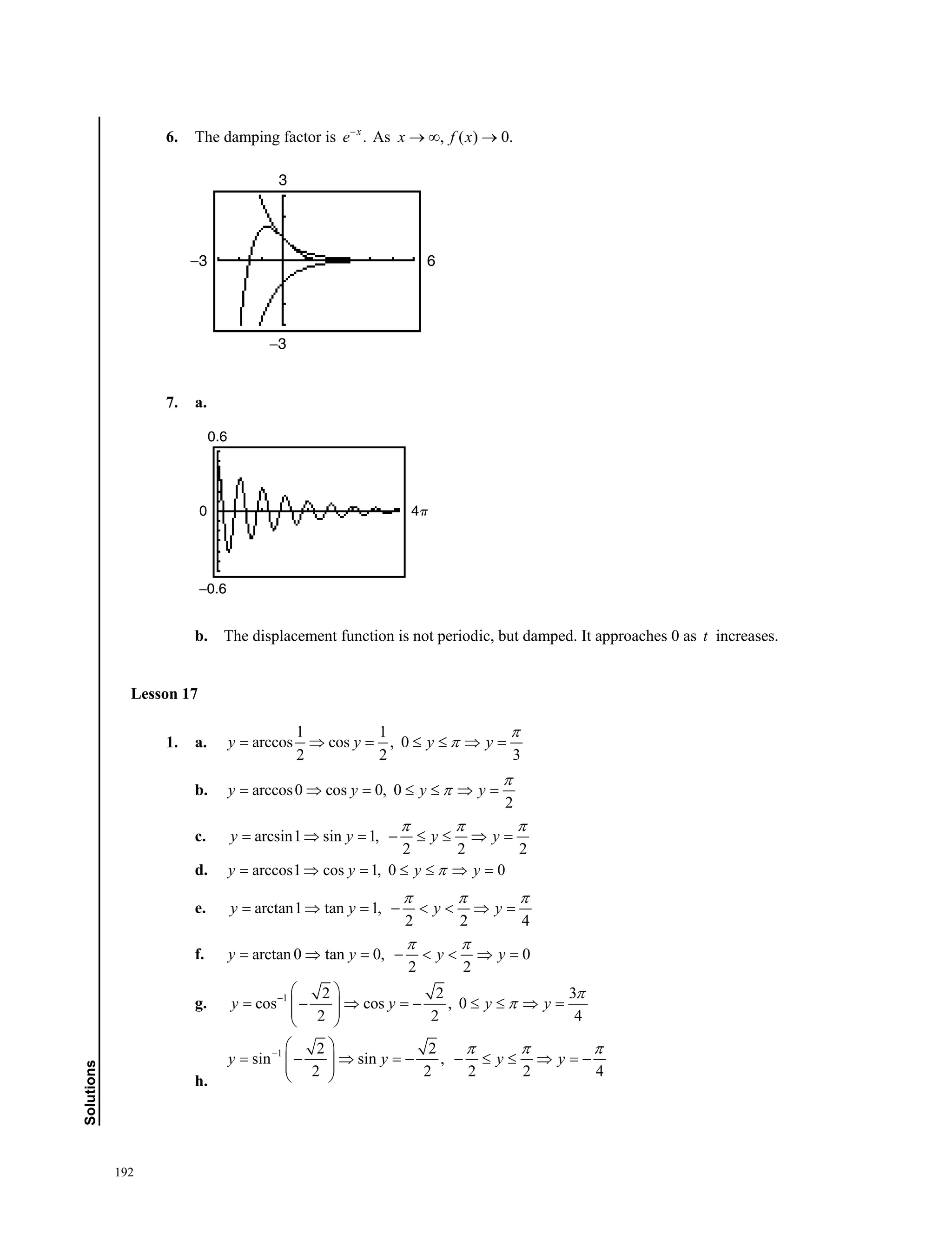

Phone: 1-800-832-2412

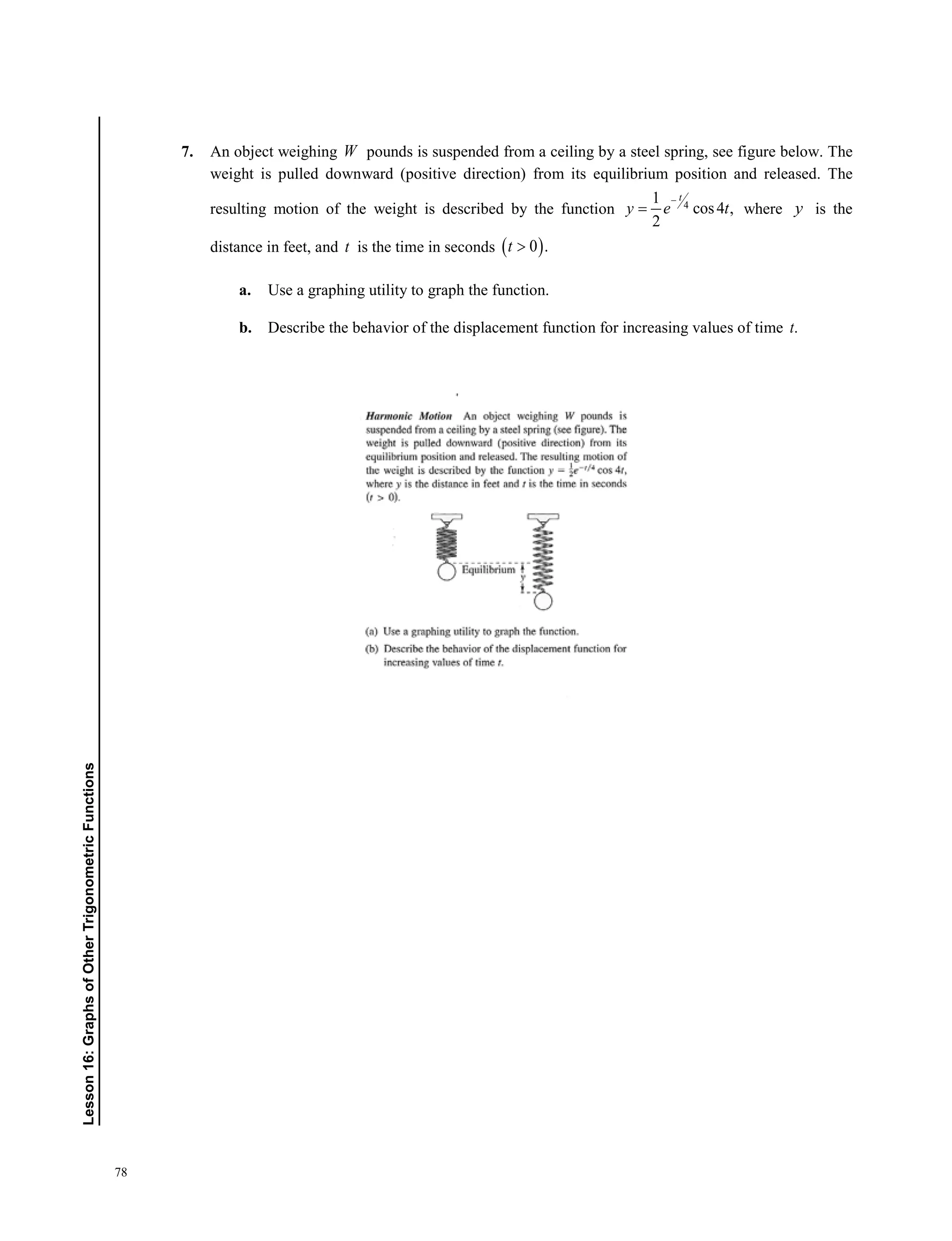

www.thegreatcourses.com

Course No. 1005 © 2011 The Teaching Company.

Cover Image: © Marek Uliasz/iStockphoto.

PB1005A

“Pure intellectual stimulation that can be popped

into the [audio or video player] anytime.”

—Harvard Magazine

“Passionate, erudite, living legend lecturers. Academia’s

best lecturers are being captured on tape.”

—The Los Angeles Times

“A serious force in American education.”

—The Wall Street Journal

High School

Topic

Mathematics

Subtopic

Course Workbook

Mathematics Describing

the Real World:

Precalculus and Trigonometry

Professor Bruce H. Edwards

University of Florida

Professor Bruce H. Edwards is Professor of Mathematics at the University of Florida, where

he has won a host of awards and recognitions. He was named Teacher of the Year in the

College of Liberal Arts and Sciences and was selected as a Distinguished Alumni Professor

by the Office of Alumni Affairs. Professor Edwards’s coauthored mathematics textbooks

have earned awards from the Text and Academic Authors Association.

PrecalculusandTrigonometryWorkbook](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/precalculusandtrigonometry-201205151455/75/Precalculus-and-trigonometry-1-2048.jpg)

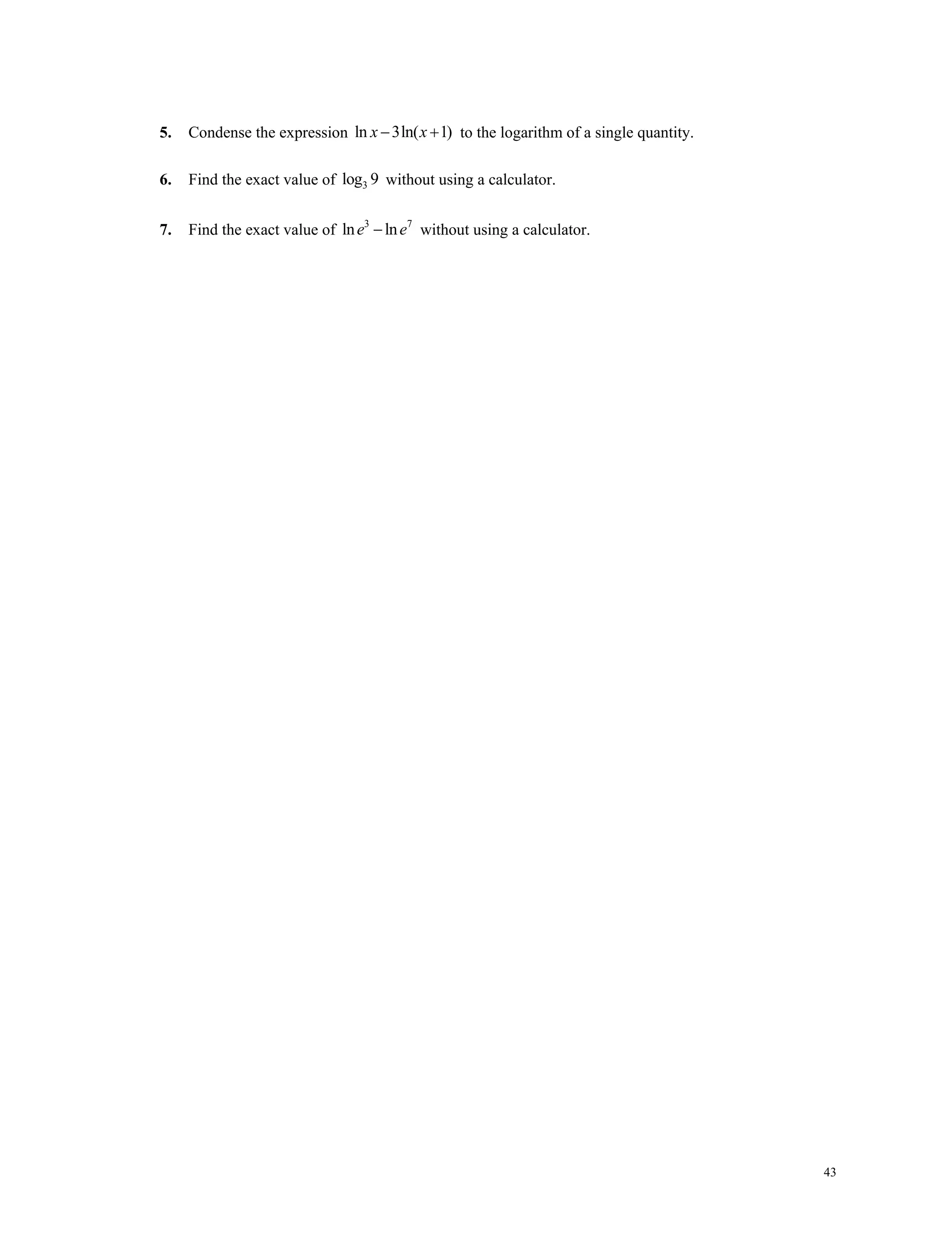

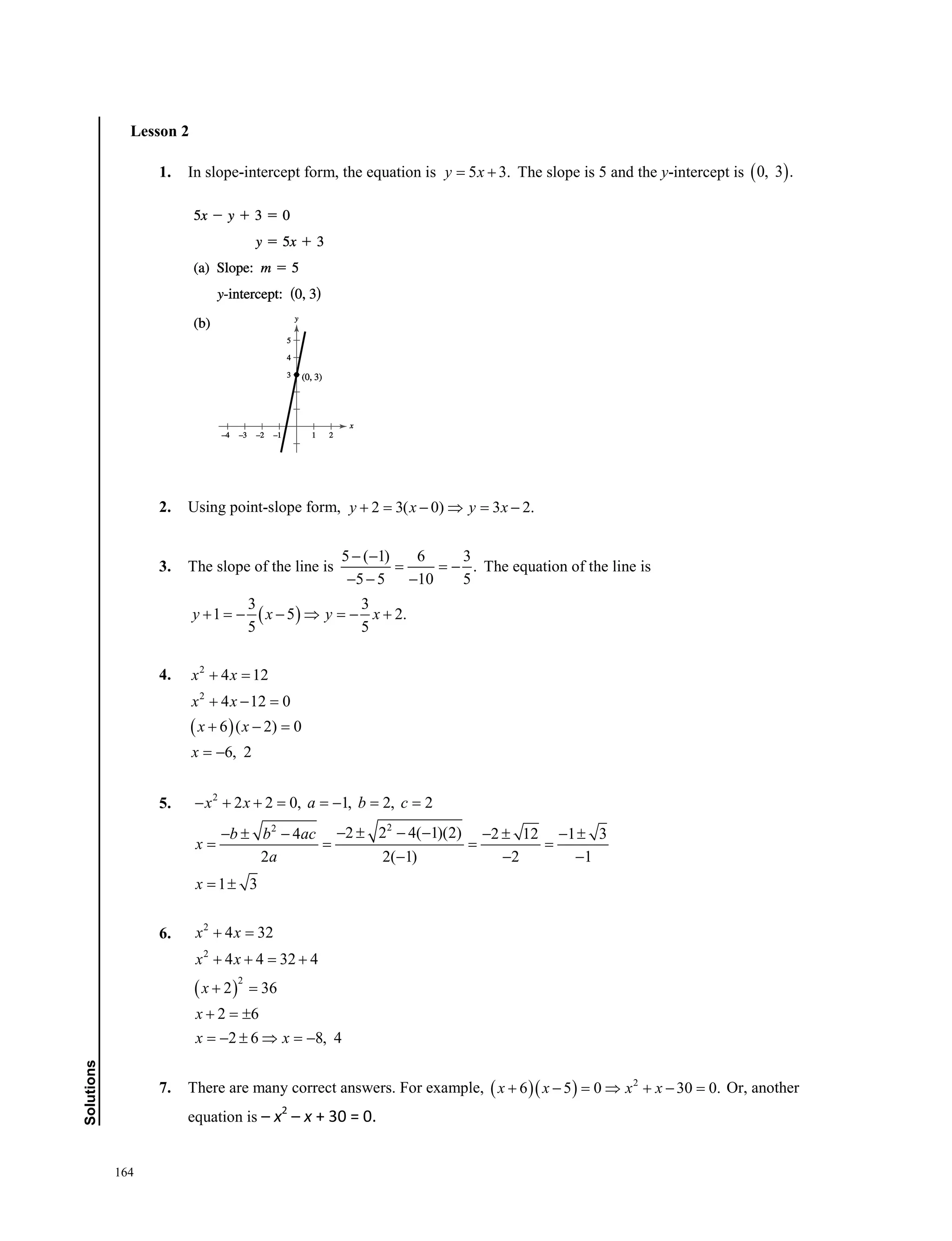

![223

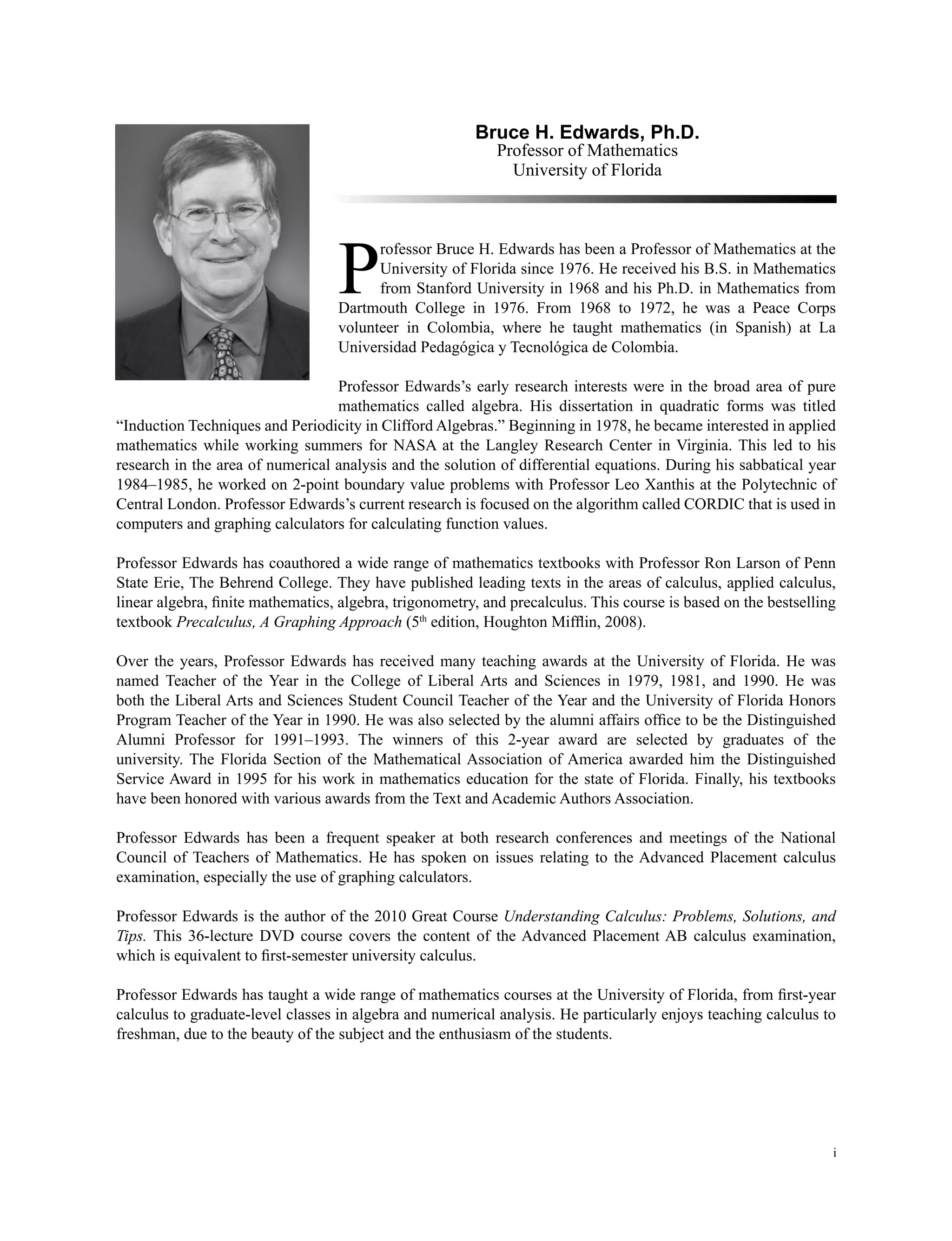

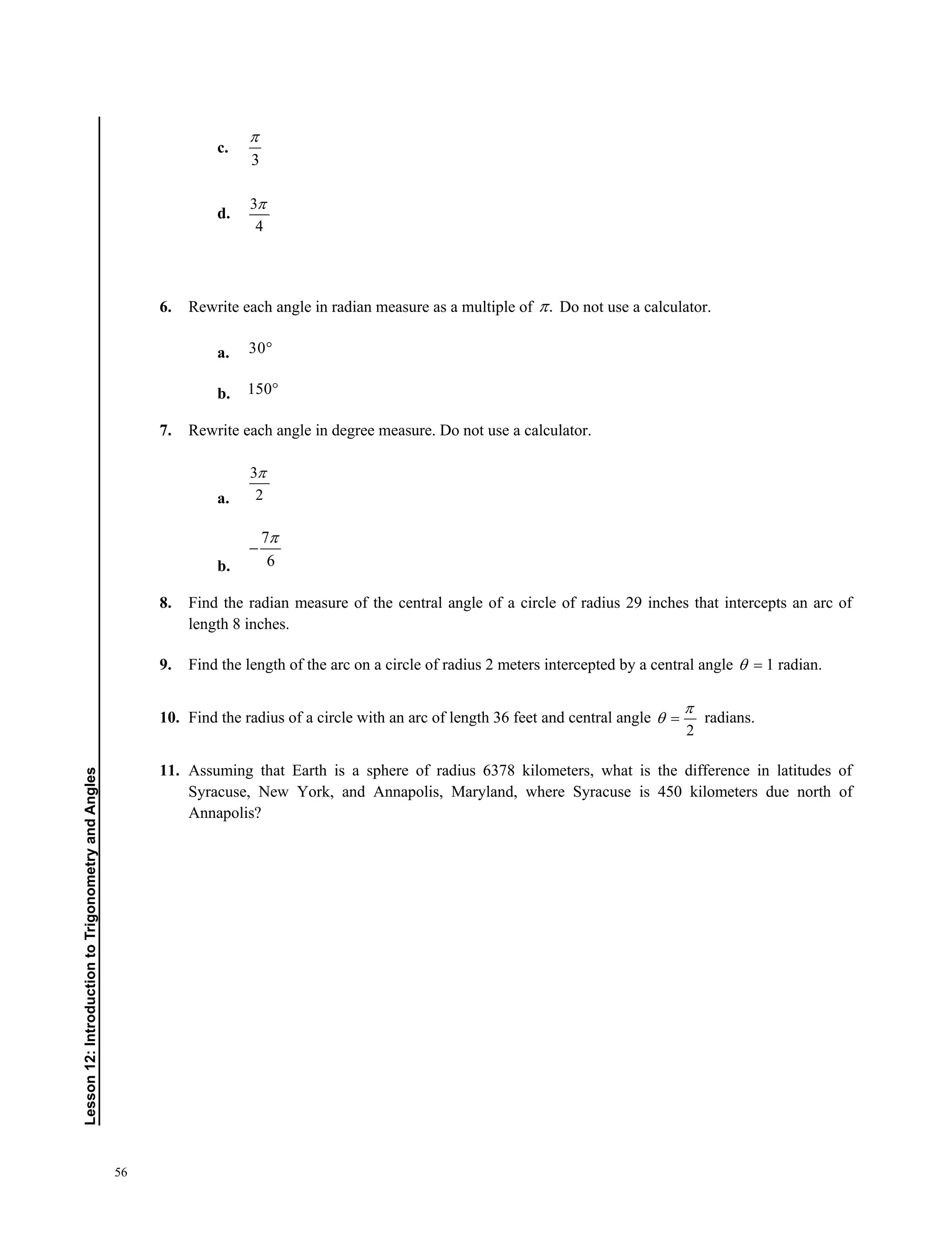

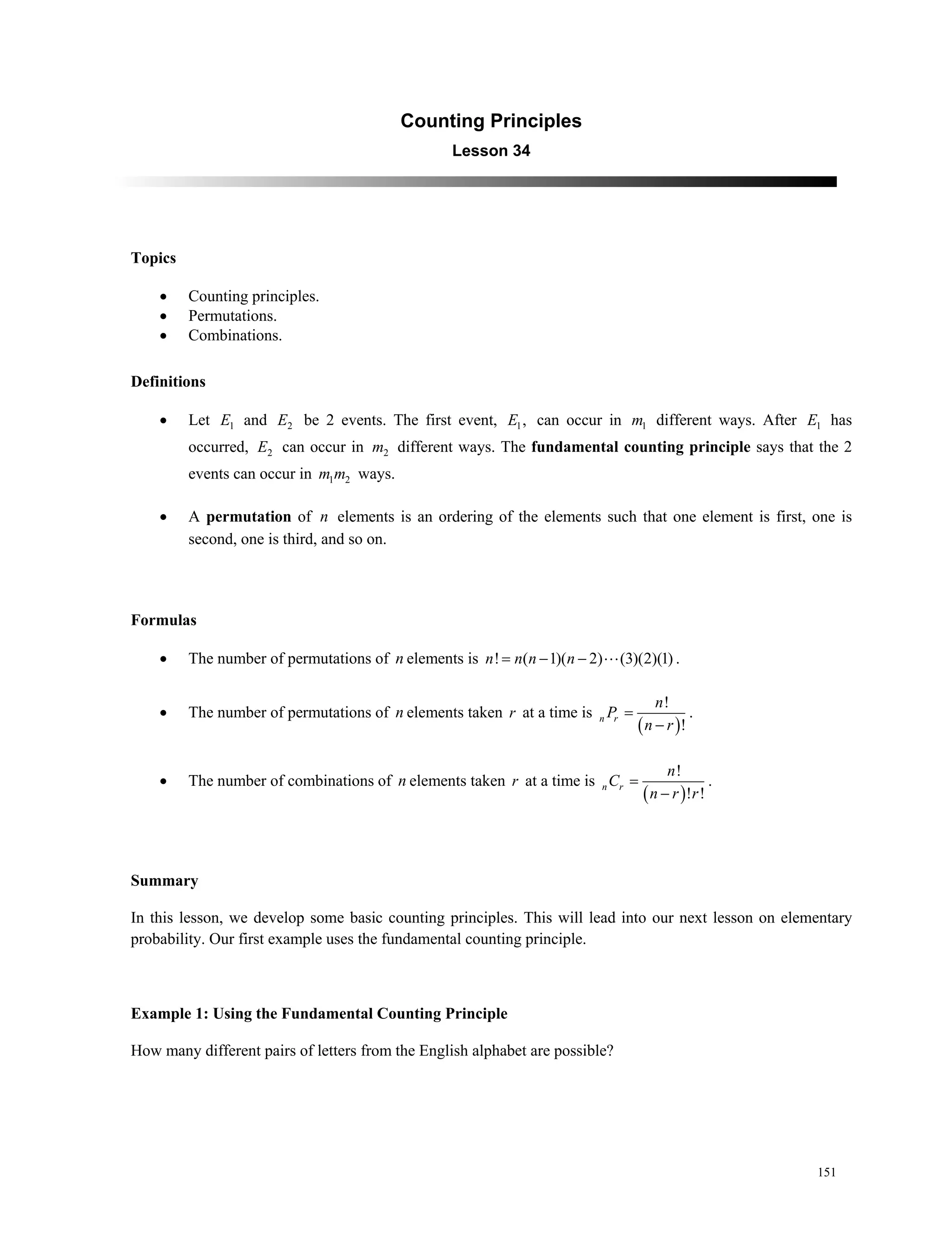

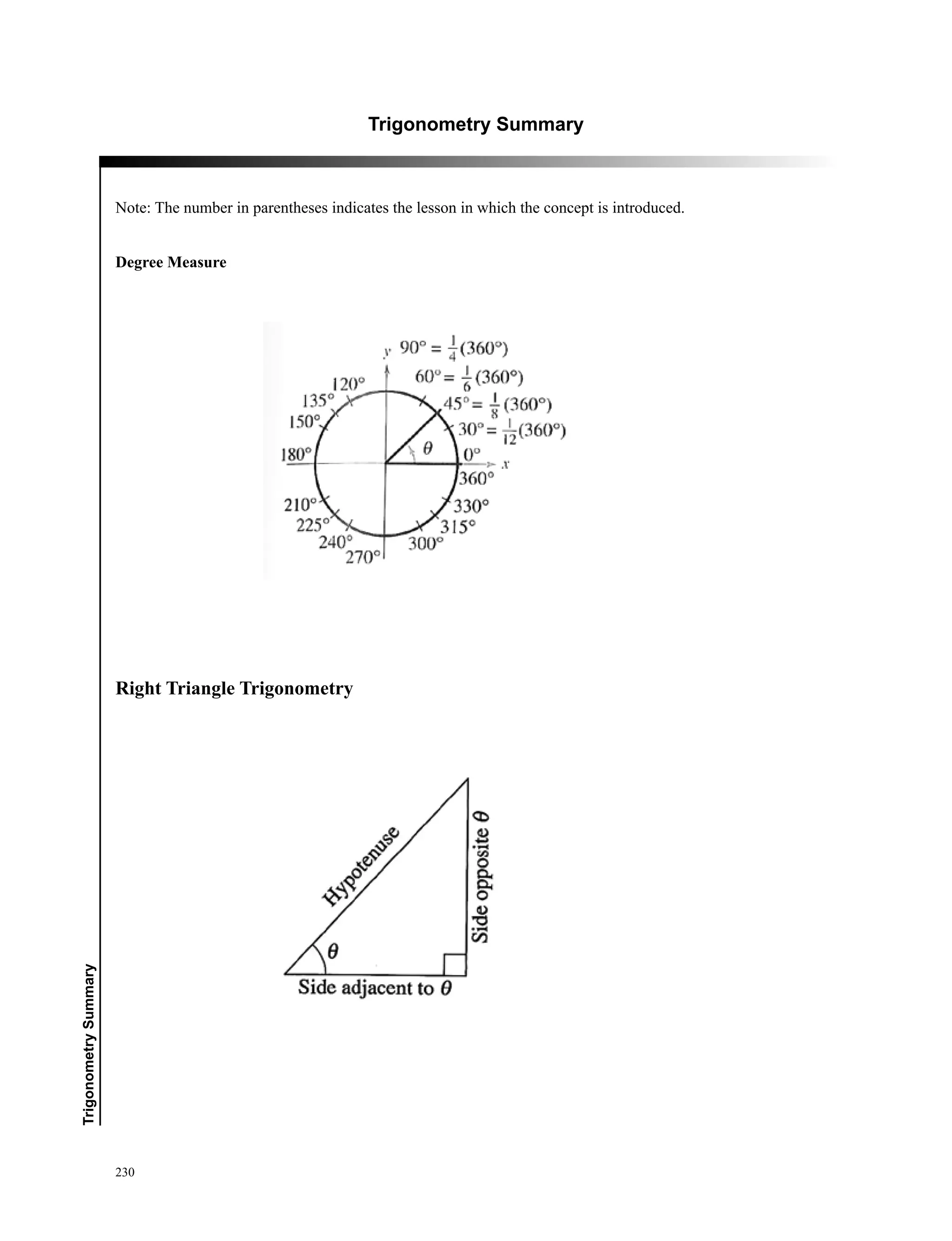

fundamental theorem of algebra (3): If f is a polynomial of degree , 0,n n then f has precisely n linear

factors: ( )( ) ( )1 2( ) ,n nf x a x c x c x c= − − − where 1 2, , nc c c are complex numbers.

Gaussian model (11): ( )2

/

.

x b c

y ae

− −

=

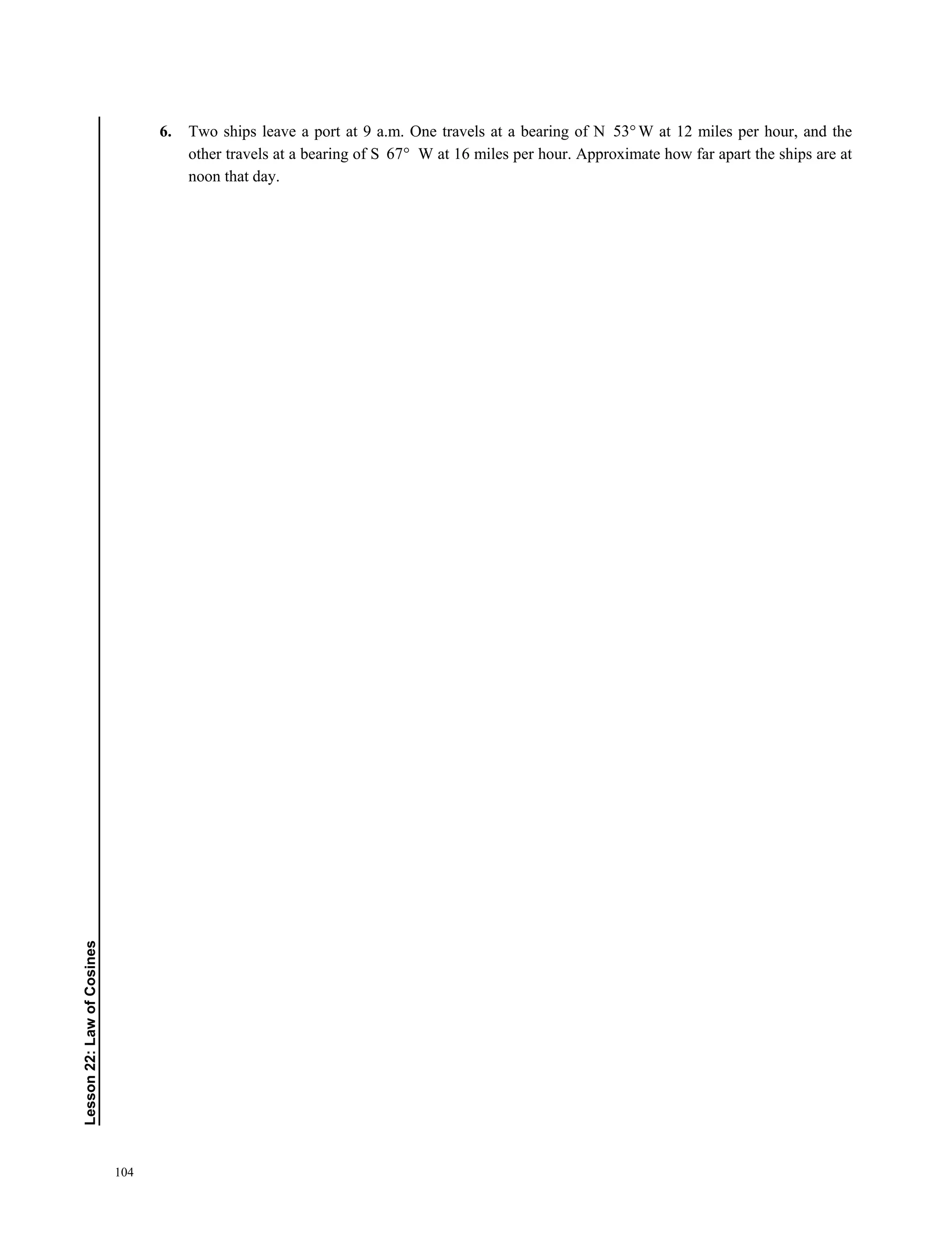

Heron’s area formula (22): A triangle with sides a, b, and c: where .

2

a b c

s

+ +

=

horizontal translations (15): Determined by solving the equations 0bx c− = and 2 .bx c π− =

intermediate value theorem (2): If a and b are real numbers, ,a b and if f is a polynomial function such that

( ) ( ),f a f b≠ then in the interval [ ], ,a b f takes on every value between ( )f a and ( ).f b In particular, if ( )f a

and ( )f b have opposite signs, then f has a zero in the interval [ ], .a b

law of cosines (22): 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2

2 cos ; 2 cos ; 2 cos .a b c bc A b a c ac B c a b ab C= + − = + − = + −

law of sines (21): .

sin sin sin

a b c

A B C

= =

linear speed (12): Arc length divided by time: .

s

t

logistic growth model (11): .

1 rx

a

y

be−

=

+

magnitude (or length) of v (23):

matrix inverse algorithm (27): To find the inverse of the n n× square matrix ,A adjoin the n n× identity

matrix and row reduce. If you are able to reduce A to ,I then I will simultaneously reduce to the inverse 1

A−

:

[ ] 1

A I I A−

→ . Otherwise, the matrix A does not have an inverse.

multiplication and division of complex numbers (24): Let ( )1 1 1 1cos sinz r iθ θ= + and ( )2 2 2 2cos sin .z r iθ θ= +

• Multiplication: ( ) ( )1 2 1 2 1 2 1 2cos sin .z z r r iθ θ θ θ= + + +

• Division: ( ) ( )1 1

1 2 1 2 2

2 2

cos sin , 0.

z r

i z

z r

θ θ θ θ= − + − ≠

Newton’s law of cooling (11): The rate of change in the temperature of an object is proportional to the difference

between the object’s temperature and the temperature of the surrounding medium.

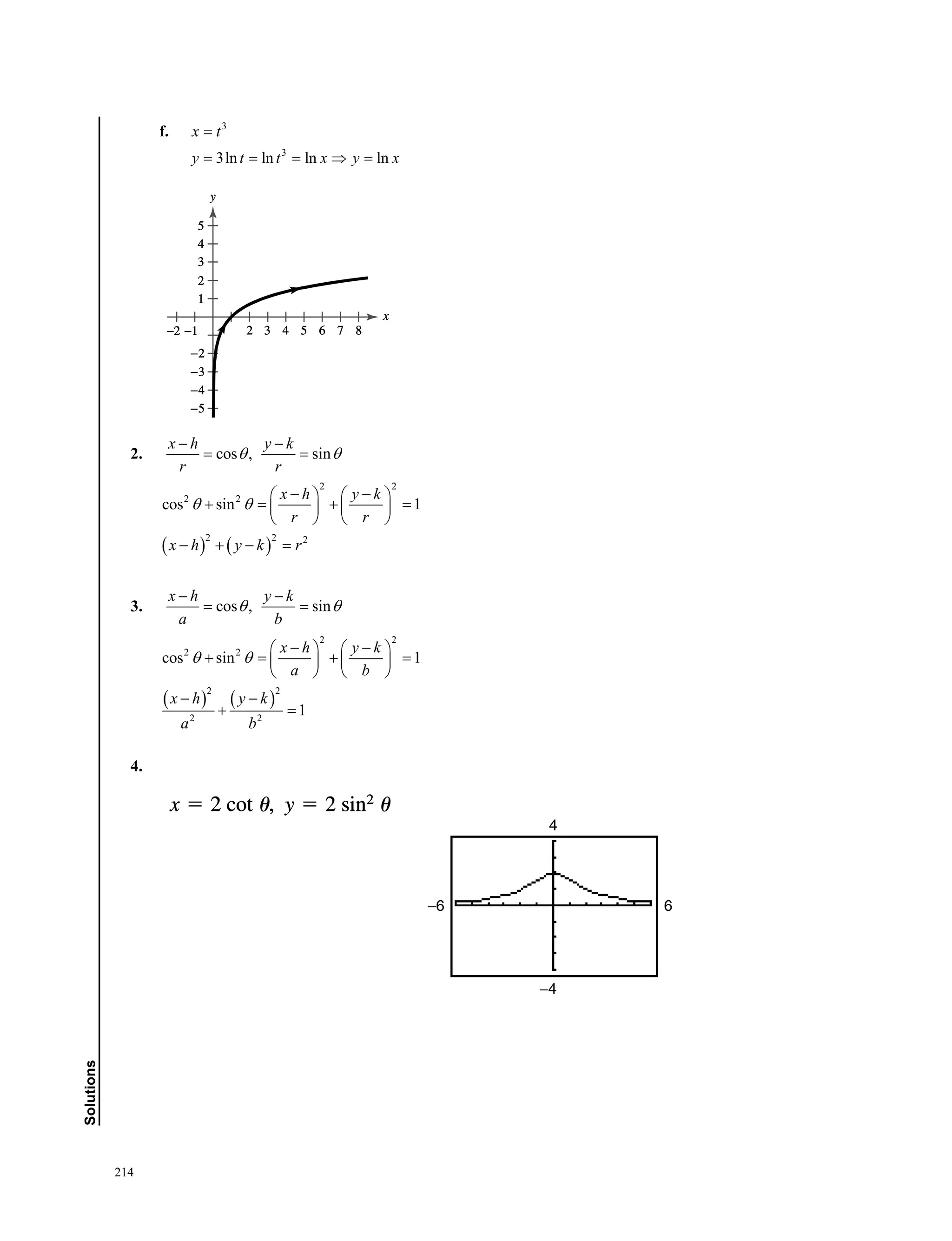

parametric equations (31): The parametric equations of the line through the 2 points ( )1 1,x y and ( )2 2,x y are

( ) ( )1 2 1 1 2 1, .x x t x x y y t y y= + − = + −](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/precalculusandtrigonometry-201205151455/75/Precalculus-and-trigonometry-229-2048.jpg)

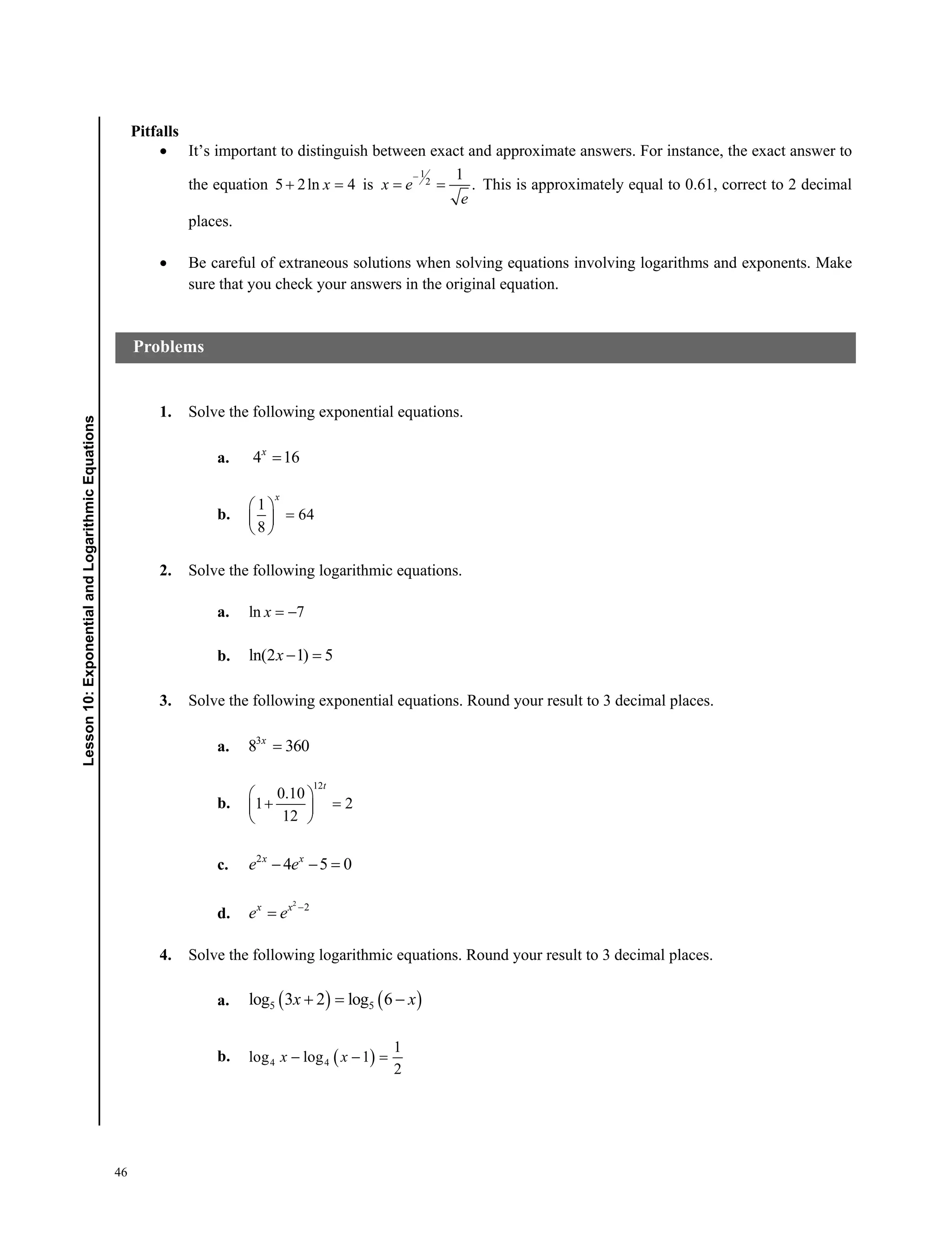

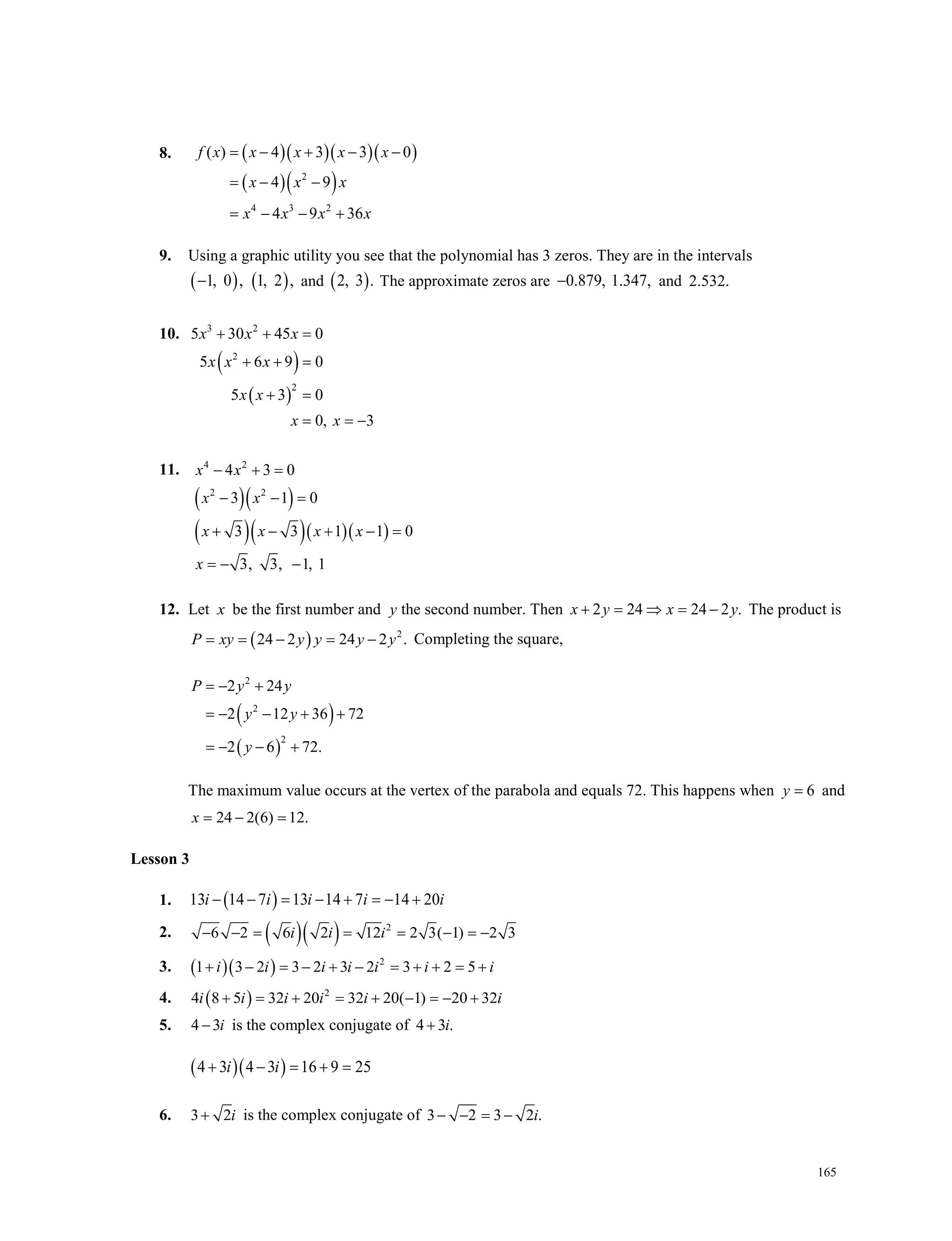

![237

Glossary

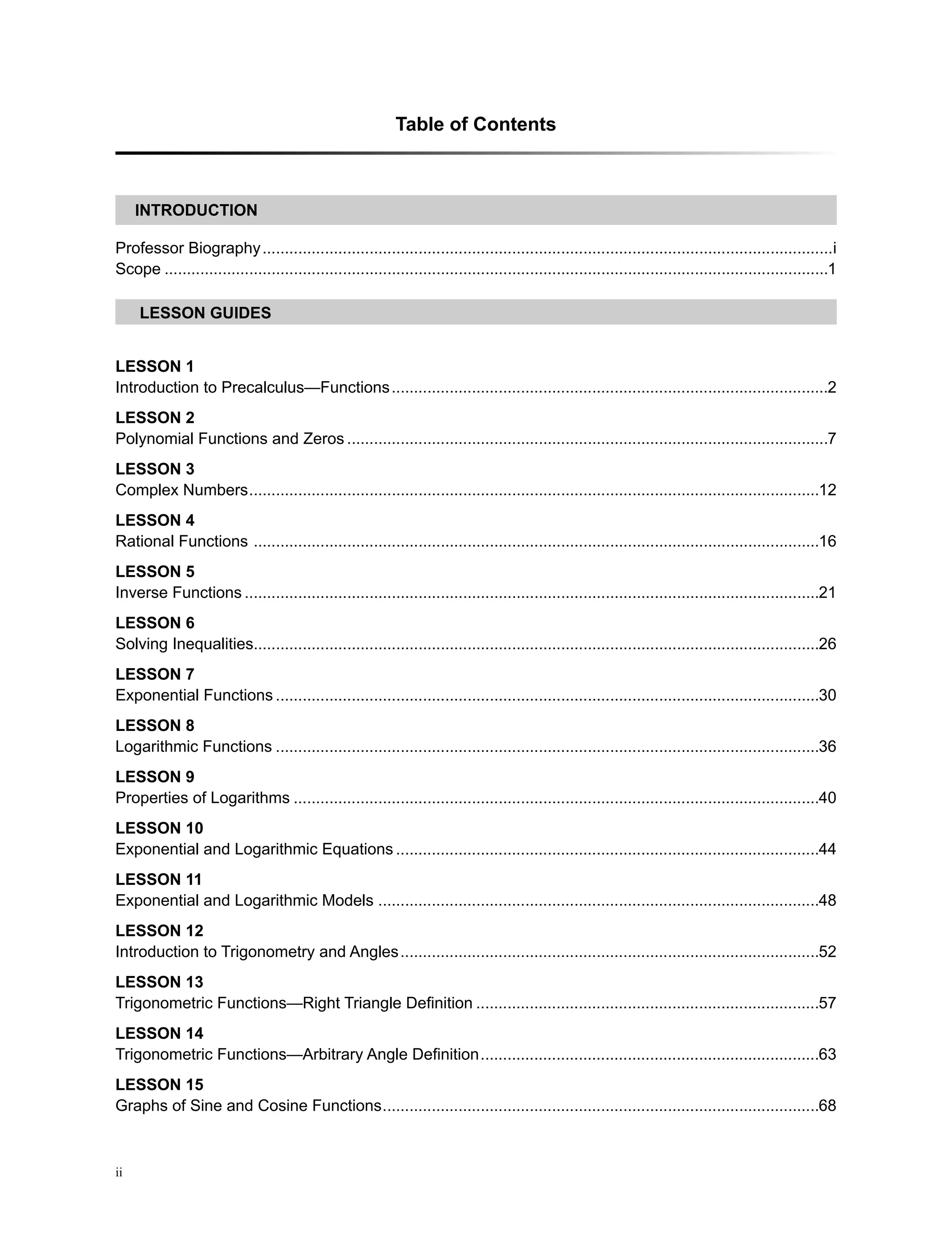

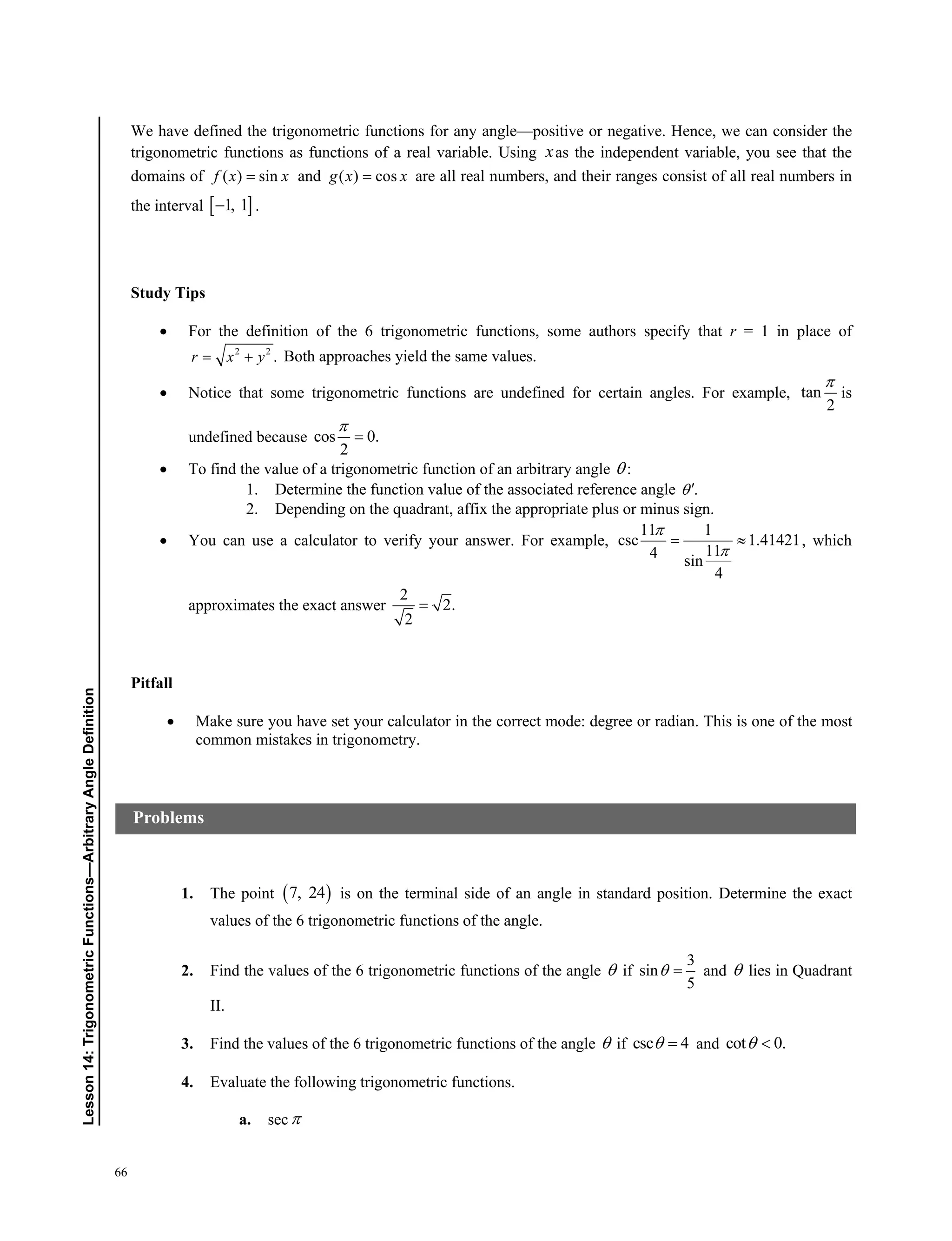

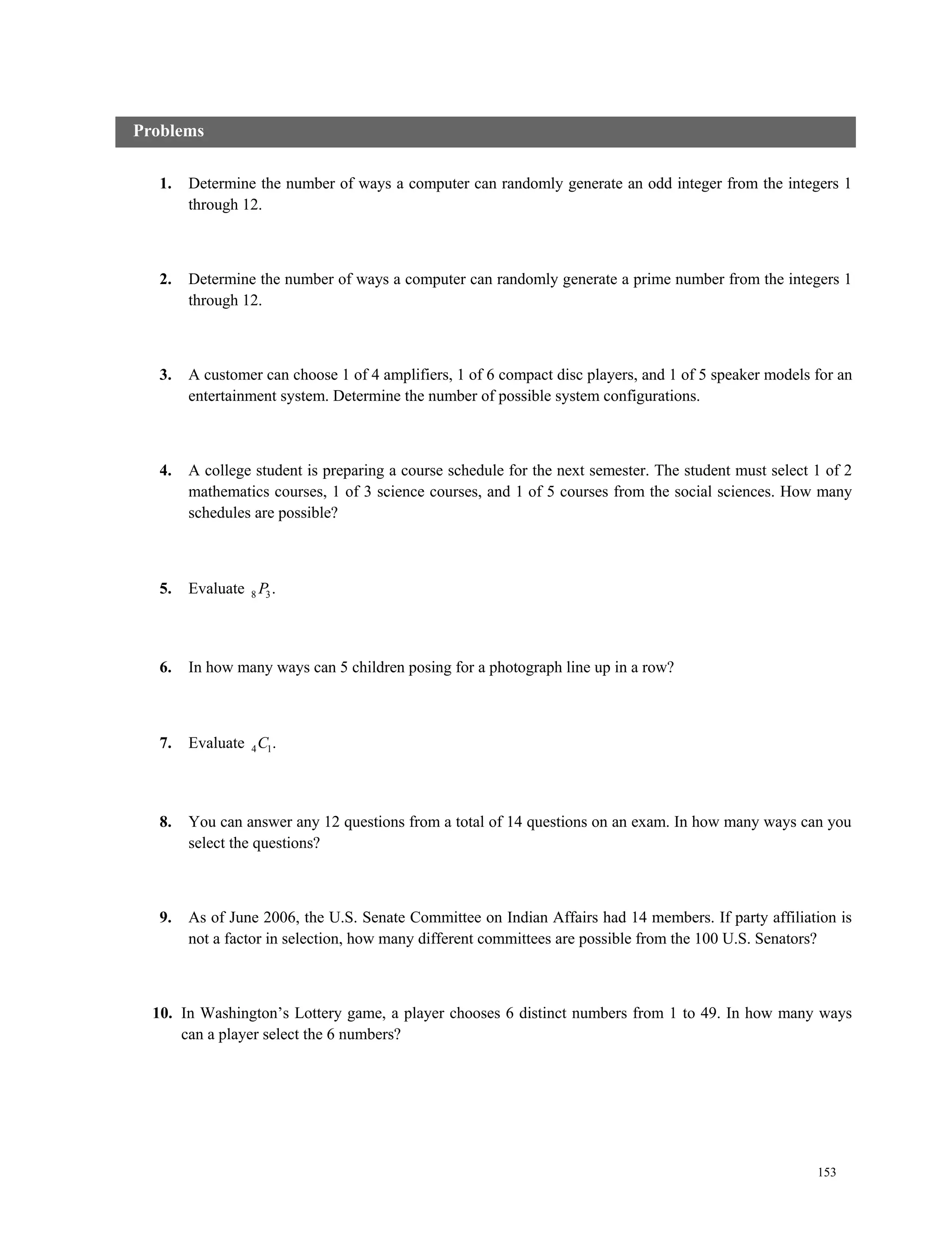

Note: The number in parentheses indicates the lesson in which the concept or term is introduced.

absolute value function (1):

, 0

( ) .

, 0

x x

f x x

x x

≥

= =

−

The absolute value of a number is always nonnegative.

absolute value of a complex number (24): See complex numbers.

acute angle (12): An angle between 0° and 90 .°

addition of functions (5): ( )( ) ( ) ( ).f g x f x g x+ = +

amplitude (15): Given the general sine and cosine functions sin( ), cos( ),y d a bx c y d a bx c=+ − =+ − where

b 0, amplitude is .a This number represents half the distance between the maximum and minimum values of

the function.

angle (12): Is determined by rotating a ray (half-line) about its endpoint. The starting position of the ray is the

initial side, and the end position is the terminal side. The endpoint of the ray is the vertex. If the origin is the

vertex and the initial side is the positive x-axis, then the angle is in standard position.

angular speed (12): Measures how fast the angle is changing. It is the central angle divided by time: .

t

θ

axis of a parabola (29): See parabola.

center of a circle (29): See circle.

center of a hyperbola (30): See hyperbola.

center of an ellipse (30): See ellipse.

circle (29): The set of all points ( ),x y in a plane that are equidistant from a fixed point ( ), ,h k called the center

of the circle. The distance between the center and any point ( ),x y on the circle is the radius, r.

closed interval (6): Closed interval [ ],a b means .a x b≤ ≤

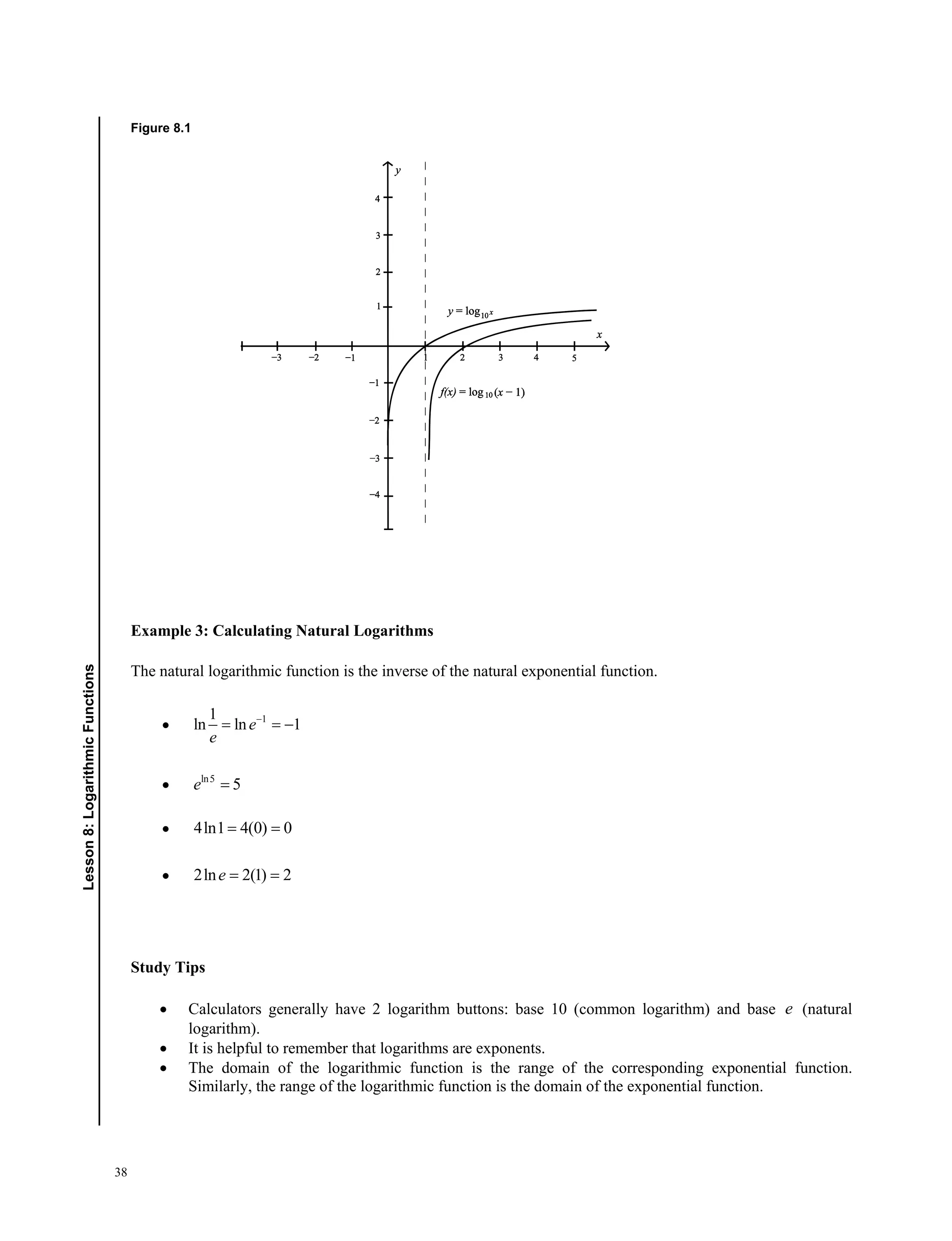

common logarithms (8): Logarithms to base 10.

complementary angles (12): Two positive angles are complements of each other if their sum is 90 .°

complement of an event (35): See experiment.

complex conjugate (3): The complex conjugate of a bi+ is .a bi−

complex numbers (3): The set of complex or imaginary numbers consists of all numbers of the form ,a bi+

where a and b are real numbers.

The absolute value or modulus of a complex number a bi+ is 2 2

.a bi a b+ = +](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/precalculusandtrigonometry-201205151455/75/Precalculus-and-trigonometry-243-2048.jpg)