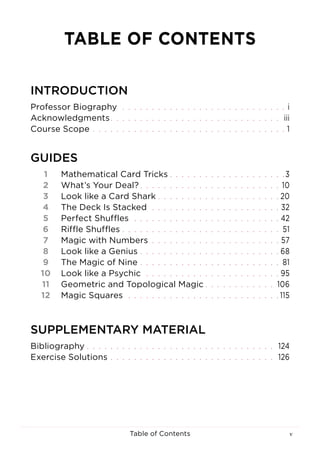

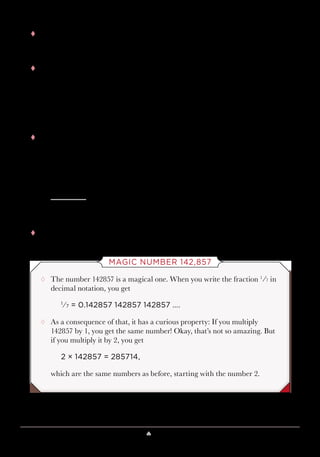

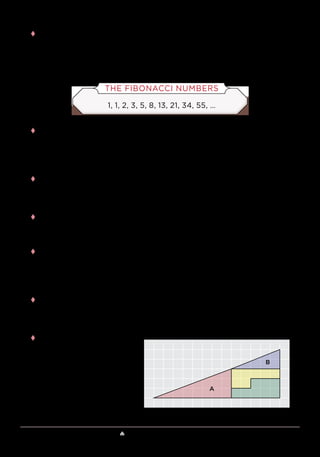

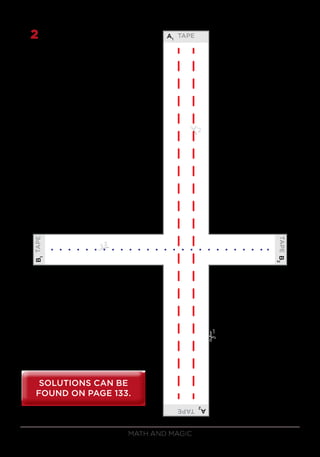

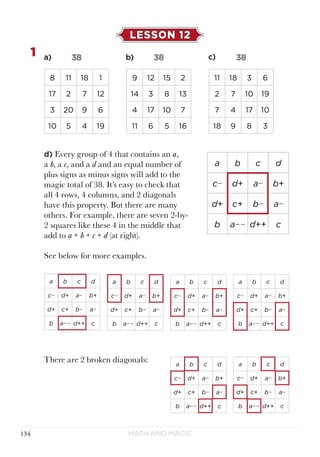

This document provides an overview of a course on using math concepts in magic tricks. The course consists of 12 lessons that teach mathematical card tricks, mental math skills, geometric and topological illusions, and magic squares. The goal is for students to learn tricks that make them appear skilled at cards, calculations, psychic abilities, and more. Many tricks use everyday props like cards and coins, with math incorporated but sometimes concealed. By the end of the course, students will be able to perform impressive tricks for others in an entertaining way.

![Published by

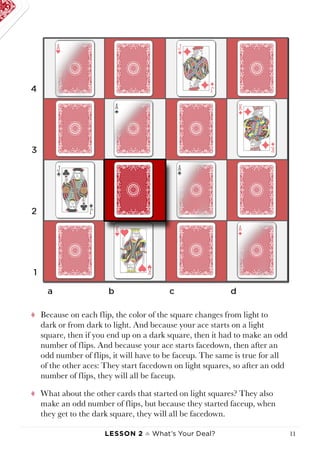

THE GREAT COURSES

Corporate Headquarters

4840 Westfields Boulevard | Suite 500 | Chantilly, Virginia | 20151‑2299

[phone] 1.800.832.2412 | [fax] 703.378.3819 | [web] www.thegreatcourses.com

Copyright © The Teaching Company, 2018

Printed in the United States of America

This book is in copyright. All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no

part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in

any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise), without the prior

written permission of The Teaching Company.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/mathandmagic-201205151443/85/Math-and-magic-2-320.jpg)