The document summarizes the Dirichlet problem for the Laplace equation on the unit disc D.

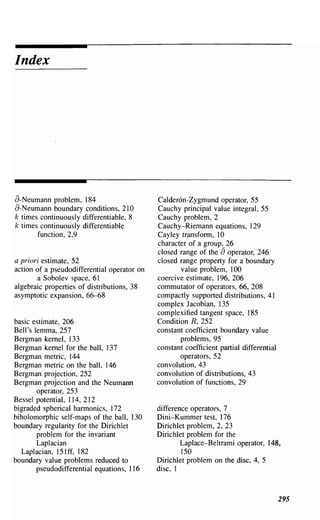

The Dirichlet problem asks us to find a function U that is harmonic (satisfies the Laplace equation) in D, continuous on D, and matches given boundary values φ on the boundary of D.

The solution can be written as a Fourier series involving the basis functions zn on D, which match the boundary values φn on ∂D. This represents the unique solution in L2. Furthermore, the series converges uniformly on compact subsets of D as the radius r approaches 1.

![2 The Dirichlet Problem in the Complex Plane

Cauchy-Riemann equations). In other words, a function satisfying of/oz == 0

may depend on z but not on z. Likewise, a function that satisfies af / 0 Z == 0

on a planar open set may depend on z but cannot depend on z.

Observe that

o

- z == 1

o

-z==O

oz oz

o o

- z ==0

oz ozz == 1.

Finally, the Laplacian is written in complex notation as

1.2 The Dirichlet Problem

Introductory Remarks

Throughout this book we use the notation C k (X) to denote the space of func-

tions that are k-times continuously differentiable on X-that is, functions that

possess all derivatives up to and including order k and such that all those

derivatives are continuous on X. When X is an open set, this notion is self-

explanatory. When X is an arbitrary set, it is rather complicated, but possible,

to obtain a complete understanding (see [STSI]).

For the purposes of this book, we need to understand the case when X is

a closed set in Euclidean space. In this circumstance we say that f is C k

on X if there is an open neighborhood U of X and a C k function j on U

1

such that the restriction of to X equals f. We write f E Ck(X). In case

k == 0, we write either CO(X) or C(X). This definition is equivalent to all

other reasonable definitions of C k for a non-open set. We shall present a more

detailed discussion of this matter in Section 3.

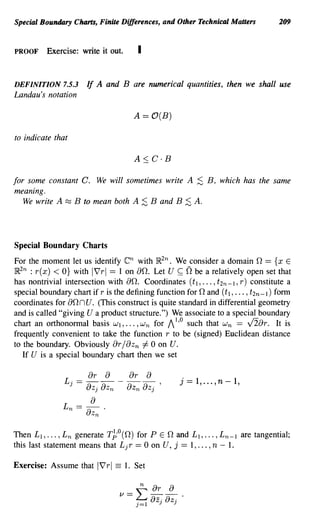

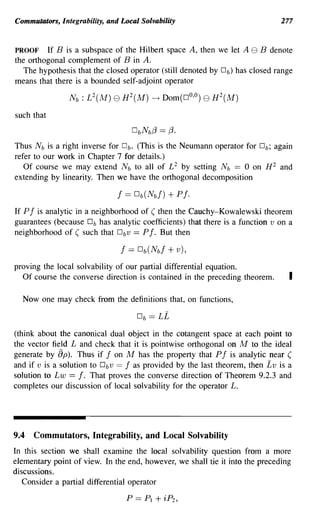

Now let us formulate the Dirichlet problem on the disc D. Let ¢ E C(oD).

The Dirichlet problem is to find a function U E C(D) n C 2 (D) such that

~U(z) == 0 if zED

U(z) == ¢ ( z) if z E aD.

REMARK Contrast the Dirichlet problem with the classical Cauchy problem

for the Lapiacian: Let S ~ lR2 == C be a smooth, non-self-intersecting curve](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/partialdifferentialequationsandcomplexanalysis-121120212851-phpapp02/85/Partial-differential-equations-and-complex-analysis-13-320.jpg)

![The Dirichlet Problem 3

s

u

FIGURE 1.1

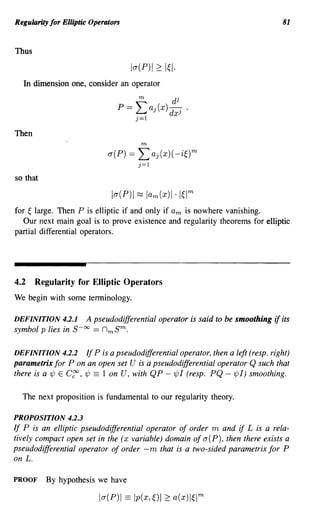

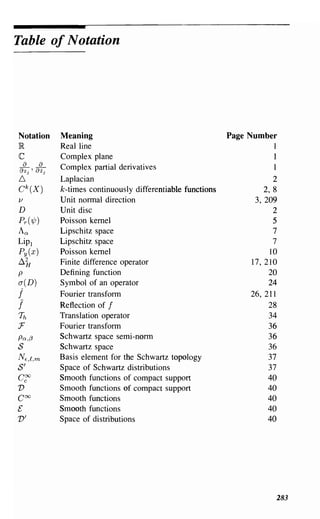

(part of the boundary of a smoothly bounded domain, for instance). Let U be

an open set with nontrivial intersection with S (see Figure 1.1). Finally, let ¢o

and ¢l be given continuous functions on S. The Cauchy problem is then

~u(z) == 0 if z E U

u(z) == ¢l (z) if z E S n U

au (z) == ¢l

av if z E S n U.

Here v denotes the unit normal direction at z E S.

Notice that the solution to the Dirichlet problem posed above is unique: if

Ul and U2 both solve the problem, then Ul - U2 is a hannonic function having

zero boundary values on D. The maximum principle thea implies that Ul == U2.

In particular, in the Dirichlet problem the specifying of boundary values also

uniquely determines the normal derivative of the solution function u.

However, in order to obtain uniqueness in the Cauchy problem, we must

specify both the value of U on S and the normal derivative of u on S. How can

this be? The reason is that the Dirichlet problem is posed with a simple closed

boundary curve; the Cauchy problem is instead a local one. Questions of when

function theory reflects (algebraic) topology are treated, for instance, by the de

Rham theorem and the Atiyah-Singer index theorem. We shall not treat them

in this book, but refer the reader to [GIL], [KRl], [DER]. I](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/partialdifferentialequationsandcomplexanalysis-121120212851-phpapp02/85/Partial-differential-equations-and-complex-analysis-14-320.jpg)

![The Dirichlet Problem 5

If we sum the two geometric series and do the necessary algebra then we find

that

27r 1 2

S 0 - -1

(r, ) - 21r 0

f it

1 - r d

( e ) 1 - 2r cos (0 - t) + r 2 t.

This last formula allows one to do the estimates to check for uniform conver-

gence, and thus to justify the change of order of the sum and the integral.

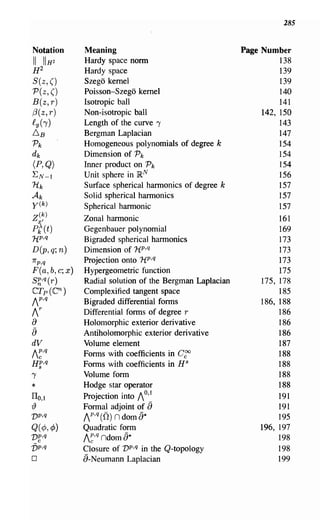

We set

=~

2

Pr ( 'lj;) 1- r

27r 1 - 2r cos ('l/J) + r2 '

and we call this function the Poisson kernel. Since the function

u(re iO ) == S(r, 0)

is the limit of the partial sums TN(r, 0) == E:=-N anrlnleinO, and since each

of the partial sums is hannonic, u is hannonic. Moreover, the partial sum

TN is the harmonic function that solves the Dirichlet problem for the data

f N(e iO ) == E:=_

N an einO . We might hope that u is then the solution of the

Dirichlet problem with data f. This is in fact true:

THEOREM 1.2.3

Let f(e it ) be a continuous function on aD. Then the function

u(reiO ) == { J~7r.f(ei(O-t))Pr(t) dt if 0 :::; r < 1

f(e~O) ifr == 1

solves the Dirichlet problem on the disc with data f.

PROOF Pick E > O. Choose 8 > 0 such that if Is - tl < 8, then If( eis ) -

f (e it )I < Eo Fix a point eiO E aD. We will first show that limr-t 1- u(re iO ) ==

f(e iO ) == u(e iO ). Now, for 0 < r < 1,

lu(re ill ) - I(e ill )/ = 11 2

71: l(e i(II-t»)Pr(t) dt - l(eill)l. (1.2.3.1)

Observe, using the sum from which we obtained the Poisson kernel, that

f27r f27r

1 IPr(t)1 dt = 1 Pr(t) dt = 1.

0 0

Thus we may rewrite (1.2.3.1) as

r

io

2

71: [I (e i(lI-t») - 1 (e ill )] Pr (t) dt =

i

r

1 tl<8

[I (e i(lI-t») - f( eill )] Pr (t) dt

+l<::,t <::'27r-JI( ei(lI-t») - I( eill )] Pr(t) dt

== I + II.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/partialdifferentialequationsandcomplexanalysis-121120212851-phpapp02/85/Partial-differential-equations-and-complex-analysis-16-320.jpg)

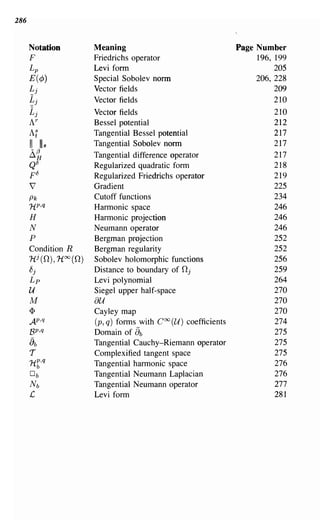

![Lipschitz Spaces 7

1.3 Lipschitz Spaces

Our first aim in this book is to study the boundary regularity for the Dirich-

let problem: if the data f is "smooth," then will -the solution of the Dirichlet

problem be smooth up to the boundary? This is a venerable question in the

theory of partial differential equations and will be a recurring theme throughout

this book. In order to formulate the question precisely and give it a careful

answer, we need suitable function spaces.

The most naive function spaces for studying the question formulated in the

last paragraph are the C k spaces, mentioned earlier. However, these spaces

are not the most convenient for our study. The reason, which is of central

importance, is as follows: We shall learn later, by a method of Hormander

[H03], that the boundary regularity of the Dirichlet problem is equivalent to the

boundedness of certain singular integral operators (see [STSI]) on the boundary.

Singular integral operators, central to the understanding of many problems in

analysis, are not bounded on the C k spaces. (This fact explains the mysteriously

imprecise formulation of regularity results in many books on partial differential

equations. It also means that we shall have to work harder to get exact regularity

results.)

Because of the remarks in the preceding paragraph, we now introduce the scale

of Lipschitz spaces. They will be somewhat familiar, but there will be some

new twists to which the reader should pay careful attention. A comprehensive

study of these spaces appears in [KR2].

Now let U ~ ~N be an open set. Let 0 < Q < 1. A function f on U is said

to be Lipschitz of order Q, and we write f E An, if

If(x + h) - f(x)1

sup

h:;tO

Ihl a + Ilfllux,(u) == IlfIIA,,(U) < 00.

x,x+hEU

We include the term IIfIILoo(u) in this definition in order to guarantee that the

Lipschitz norm is a true norm (without this term, constant functions would have

"norm" zero and we would only have a semi-norm). In other contexts it is

useful to use IlfIlLP(u) rather than IlfIILOO(U). See [KR3] for a discussion of

these matters.

When Q == 1 the "first difference" definition of the space An makes sense,

and it describes an important class of functions. However, singular integral

operators are not bounded on this space. We set this space of functions apart

by denoting it differently:

sup If(x + h) - f(x)1

Ihl +

IIIII Loo(U) < 00.

h=¢.O

x,x+hEU](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/partialdifferentialequationsandcomplexanalysis-121120212851-phpapp02/85/Partial-differential-equations-and-complex-analysis-18-320.jpg)

![The Dirichlet Problem in the Complex Plane

The space Lipl is important in geometric applications (see [FED]), but less so

in the context of integral operators. Therefore we define

IIfIIA ==

If(x + h) + I(x - h) - 2/(x)1 IIIII

1 (U) sup

h:;iO

Ihl + LCXJ(U) < 00.

x,x+h,x-hEU

Inductively, if 0 < k E Z and k < a ::; k + 1, then we define a function f

on U to be in Aex if I is bounded, I E C1(U), and any first derivative Djl

lies in Aex - l . Equivalently, I E A ex if and only if f is bounded and, for every

nonnegative integer f < Q and multiindex {3 of total order not exceeding f we

have (8 j 8x)(3 I exists, is continuous, and lies in Aex - f .

The space Lip k' 1 < k E Z, is defined by induction in a similar fashion.

REMARK As an illustration of these ideas, observe that a function 9 is in

AS / 2(U) if 9 is bounded and the derivatives 8gj8xj, 82gj8xj8xk exist and lie

in A1/ 2 •

Prove as an exercise that if Q' > Q then Aexl ~ A ex . Also prove that the

Weierstrass nowhere-differentiable function

00

F(O) == L 2- e j i2ie

j=O

is in Al (0, 27r) but not in LiPl (0, 21r). Construct an analogous example, for

each positive integer k, of a function in A k Lip k'

If U is a bounded open set with smooth boundary and if 9 E Aex(U) then

does it follow that 9 extends to be in A ex (U)? I

Let us now discuss the definition of C k spaces in some detail. A function

f on an open set U ~ }RN is said to be k-times continuously differentiable,

written lEek (U), if all partial derivatives of I up to and including order k

exist on U and are continuous. On }Rl , the function I (x) == Ixllies in CO C 1•

Examples to show that the higher order Ok spaces are distinct may be obtained

by anti-differentiation. In fact, if we equip Ok (U) with the norm

IlfIICk(U) == IlfIIL(X)(U) + L II (~::) II

lal::;k Loo(U)

'

then elementary arguments show that C k + 1 (U) is contained in, but is nowhere

dense in, Ck(U).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/partialdifferentialequationsandcomplexanalysis-121120212851-phpapp02/85/Partial-differential-equations-and-complex-analysis-19-320.jpg)

![Lipschitz Spaces 9

It is natural to suspect that if all the k th order pure derivatives (a/ax j )f f exist

and are bounded, 0 ::; /!, ::; k, then the function has all derivatives (including

mixed ones) of order not exceeding k and they are bounded. In fact Mityagin

and Semenov [MIS] showed this to be false in the strongest possible sense.

However, the analogous statement for Lipschitz spaces is true-see [KR2].

Now suppose that U is a bounded open set in ~N with smooth boundary. We

would like to talk about functions that are C k on U == U u au. There are three

ways to define this notion:

I. We say that a function f is in C k (0) if f and all its derivatives on U of

order not exceeding k extend continuously to (j.

II. We say that a function f is in C k (0) if there is an open neighborhood

W of 0 and a C k function F on W such that Flo == f.

III. We say that a function f is in Ck(U) if f E Ck(U) and for each Xo E au

and each multiindex Q such that IQ I ::; k the limit

ao:

lim

U3x----+xo

-a f(x)

xO:

exists.

We leave as an exercise for the reader to prove the equivalence of these

definitions. Begin by using the implicit function theorem to map U locally to a

boundary neighborhood of an upper half-space. See [HIR] for some help.

REMARK A basic regularity question for partial differential equations is as

follows: consider the Laplace equation

.6u == f.

If f E ;'0: (~N ), then where (Le. in what smoothness class) does the function u

live (at least locally)?

In many texts on partial differential equations, the question is posed as "If

f E C k(~N) then where does u live?" The answer is generally given as

"u E Cl~:2-f for any E > 0." Whenever a result in analysis is formulated in

this fashion, it is safe to assume that either the most powerful techniques are not

being used or (more typically) the results are being formulated in the language

of the incorrect spaces. In fact, the latter situation obtains here. If one uses

the Lipschitz spaces, then there is no t-order loss of regularity: f E Ao: (~N)

implies that u is locally in AO:+ 2 (IR N ). Sharp results may also be obtained by

using Sobolev spaces. We shall explore this matter in further detail as the book

develops. I](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/partialdifferentialequationsandcomplexanalysis-121120212851-phpapp02/85/Partial-differential-equations-and-complex-analysis-20-320.jpg)

![Boundary Regularity 13

As a result, line (1.4.1.1) equals

Ii: ::2 Py (X - t) [J(t) - f(x)] dtl

< C i: ::2 I Py (X - t)llx - til> dt

cjOO 1

2Y (3(x - tf - ~2) IIX _ tl a dt

- 00 [ (x - t) 2 + y2]

2

C JOO Iy(3t - y2) Iit ia dt

-00 (t 2 + y2)3

OO 1

C a-2

y J -00 (t 2 + 1)2-a/2

dt

C ya-2 .

This completes the proof of Fact 1.

PROOF OF FACT 2 First notice that, for any x E IR,

:; ~1

7r -00

00

[(x - t)2 + y2]

2

I(x - tf + y - 22y21If(t)1 dtl

y=2

<~

- 7r

1

-00

00

If(t)1

(x - t)2 + y2

dtl

y=2

::; C . IIfIlLOO(~).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/partialdifferentialequationsandcomplexanalysis-121120212851-phpapp02/85/Partial-differential-equations-and-complex-analysis-24-320.jpg)

![14 The Dirichlet Problem in the Complex Plane

Now, if Yo ~ 2, then from Fact 1 we may calculate that

1~~(xO,Yo)1 ~ 11 ~:~(XO,Y)dY+ ~~(XO,2)1

YO

~ l YO

y"-2dy+ 1~~(XO,2)1

< Ca [ya-l

- 0 + 2a - l

] + C2

A nearly identical argument shows that

au( xo,yO) I ~

ay c 'a 1

Yo-

I

when 0 ::; Yo < 2.

We have proved Facts I and 2 and therefore have completed our estimates of

term I.

The estimate of I I I is just the same as the estimate for I and we shall say

no more about it.

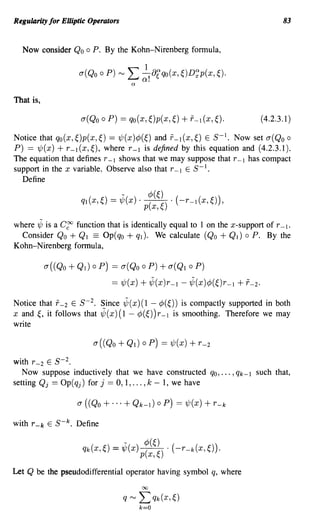

For the estimate of II, we write A == (aI, a2) and B == (b l , b2). Then

lu(A) - u(B)1 == lu(al' a2) - u(b l , b2)1

::; lu( aI, a2) - u(b l , a2) I + lu(b l , a2) - 'u(b l , b2) I

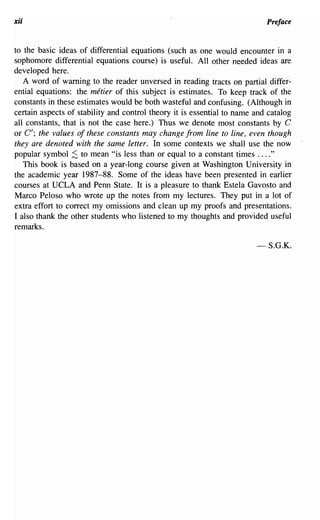

Assume for simplicity that al < bl as shown in Figure 1.2. Now set 7](t) =

(al + t, a2),O < t < bl - al. Then

bl - al d

I I I ==

l o

- (u 0 7]) (t) dt

dt

= Jo

rbl-al d

dt

1 00

-oc Pa2 (al + t - 8)f(8) d8 dt

I

I

bl-all°O -d Pa2(al + t -

d

==

l o -00 t

s) [f(s) - f(t)] ds dt.

We leave it as an exercise for the reader to see that this last expression, in

absolute value, does not exceed GIHla.

The tenn 112 is estimated in the same way that we estimated I. I](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/partialdifferentialequationsandcomplexanalysis-121120212851-phpapp02/85/Partial-differential-equations-and-complex-analysis-25-320.jpg)

![16 The Dirichlet Problem in the Complex Plane

THEOREM 1.4.3

If f E AI(~), then

u(x, y) == l Py(x - t)f(t) dt

We break the proof up into a sequence of lemmas.

LEMMA 1.4.4

Fix y > O. Take (xo, YO) E U. Then

u(xo, Yo) = l Y

y' ()~~2 u(xo, Yo + y') dy' - y :y u(xo, Yo + y) + u(xo, y + Yo)·

PROOF Note that when y == 0, then the right-hand side equals O-O+u(xo, Yo).

Also, the partial derivative with respect to y of the right side is identically zero.

That completes the proof. I

LEMMA 1.4.5

If f E Al (~), then

PROOF Notice that, because u is harmonic,

I::2 ul = I::2 ul

=I ::2 f Py(x - t)f(t) dtl

= If (::2 Py(x - t)) f(t) dtl

= If (::2 Py(x - t)) f(t) dtl

= IJ (::2 Py(t)) f(x - t) dtl

= ~ IJ (:t: Py(t)) [I(x + t) + I(x - t) - 2f(x)] dtl](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/partialdifferentialequationsandcomplexanalysis-121120212851-phpapp02/85/Partial-differential-equations-and-complex-analysis-27-320.jpg)

![Boundary Regularity 19

Finally, the same reasoning gives

11111::; IHI 2 . sup 1V'2 u (xo+th l ,yo+th2 +y)1

It I:::; I

::; C . IHI 2 . y-I.

Now we take y == 21HI. The estimates on 1,11,111 then combine to give

1~~u(X)1 ::; CIHI·

This is the desired estimate on u. I

REMARK We have proved that if f E Al (IR) then u == Pyf E Al (U) us-

ing the method of direct estimation. An often more convenient, and natural,

methodology is to use interpolation of operators, as seen in the next theorem.

I

THEOREM 1.4.8

Let V ~ IRm, W ~ IRn be open with smooth boundary. Fix 0 < 0: < (3

and assume that T is a linear operator such that T : Aa(V) ~ Aa(W) and

T : A{J(V) ~ A{J(W). Then, for all 0: < 1 < (3 we have T : A,(V) ~ A,(W).

Interpolation of operators, presented in the context of Lipschitz spaces, is

discussed in detail in [KR2]. The subject of interpolation is discussed in a

broader context in [STW] and [BOL]. Here is an application of the theorem:

Let 0: == 1/2, {3 == 3/2, and let T be the Poisson integral operator from

functions on IR to functions on U. We know that

and

We may conclude from the theorem that

Thus we have a neater way of seeing that Poisson integration is well behaved

on AI.

REMARK Twenty years ago it was an open question whether, if T is a bounded

linear operator on CO and on C 2 , it follows that T is a bounded linear operator

on C l . The answer to this question is negative; details may be found in [MIS].

In fact, AI is the appropriate space that is intennediate to CO and C2.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/partialdifferentialequationsandcomplexanalysis-121120212851-phpapp02/85/Partial-differential-equations-and-complex-analysis-30-320.jpg)

![20 The Dirichlet Problem in the Complex Plane

One might ask how Poisson integration is behaved on Lip I (IR). Set f(x) ==

Ixl· ¢(x) where ¢ E Cgo(IR), ¢ == 1 near O. One may calculate that

(x, Y ) == P yf (x ) == ~ In [ (1 - 2x) + y2 . (1 +2x) + y2]

2 2

U 2- 2 2

X +y x +y

+x 1- x 1+ x]

[ arctan -y- - arctan -y-

+ (smooth error).

Set x == O. Then, for y small,

Again, we see that the classical space Lipi does not suit our purposes, while

Al does. We shall not encounter LiPI any more in this book. The space Al was

invented by Zygmund (see [ZYG]), who called it the space of smooth functions.

He denoted it by A*.

Here is what we have proved so far: if ¢ is a piece of Dirichlet data for

the disc that lies in An (aD), 0 < a < 2, then the solution u to the Dirichlet

problem with that data is An up to the boundary. We did this by transferring

the problem to the upper half-space by way of the Cayley transform and then

using explicit calculations with the Poisson kernel for the half-space.

1.5 Regularity of the Dirichlet Problem on a Smoothly Bounded

Domain and Conformal Mapping

We begin by giving a precise definition of a domain "with smooth boundary":

DEFINITION 1.5.1 Let U ~ C be a bounded domain. We say that U has

smooth boundary if the boundary consists of finitely many curves and each of

these is locally the graph of a COO function.

In practice it is more convenient to have a different definition of domain with

smooth boundary. A function p is called a defining function for U if p is defined

in a neighborhood W of au, l p i= 0 on au, and wnu == {z E W : p(z) < O}.

Now we say that U has smooth (or C k ) boundary if U has a defining function

p that is smooth (or C k ). Yet a third definition of smooth boundary is that the

boundary consists of finitely many curves rj, each of which is the trace of a

smooth curve r( t) with nonvanishing gradient. We invite the reader to verify

that these three definitions are equivalent.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/partialdifferentialequationsandcomplexanalysis-121120212851-phpapp02/85/Partial-differential-equations-and-complex-analysis-31-320.jpg)

![Regularity of the Dirichlet Problem 21

"",---- ........... ,

/ ", "

/_-........" U ",

/-- ........

""

I / " / /

~ '

laD'

Iw /

I / ~ I

I I

I

aD

/ I I I

/ / I I /

I ( / / I

"

au' / / / ",/

"'-..... -. ' - _ / "'B /

"........

" ........ _--_/ ",

/

FIGURE 1.3

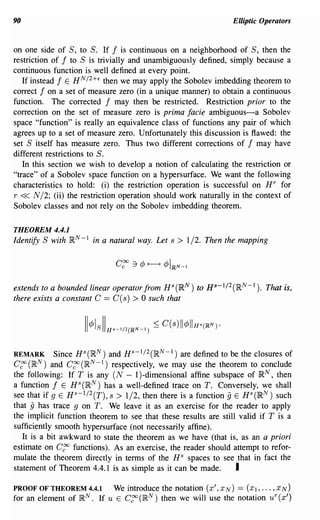

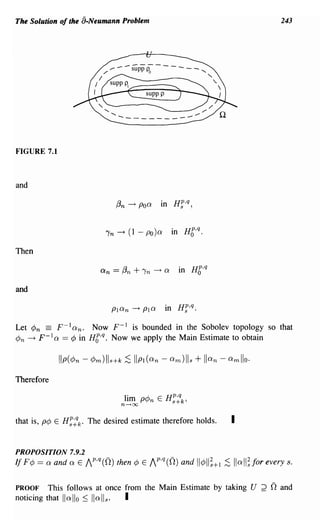

Our motivating question for the present section is as follows:

Let n ~ C be a bounded domain with smooth boundary. Assume

that! E An (an). If u E C(n) satisfies (i) u is harmonic on nand

(ii) ulan == !, then does it follow that u E An(n)?

Here is a scheme for answering this question:

Step 1: Suppose at first that U is bounded and simply connected.

Step 2: By the Riemann mapping theorem, there is a conformal mapping ¢ :

U ~ D. Here D is the unit disc. We would like to reduce our problem

to the Dirichlet problem on D for the data ! 0 ¢ - 1•

In order to carry out this program, we need to know that ¢ extends smoothly

to the boundary. It is a classical result of Caratheodory [CAR] that if a simply

connected domain U has boundary consisting of a Jordan curve, then any con-

formal map of the domain to the disc extends univalently and bicontinuously to

the boundary. It is less well known that Painleve, in his thesis [PAl], proved that

when U has smooth boundary then the conformal mapping extends smoothly to

the boundary. In fact, Painleve's result long precedes that of Caratheodory.

We shall present here a modem approach to smoothness to the boundary

for conformal mappings. These ideas come from [KERl]. See also [BKR]

for a self-contained approach to these matters. Our purpose here is to tie the

smoothness-to-the-boundary issue for mappings directly to the regularity theory

of the Dirichlet problem for the Laplacian.

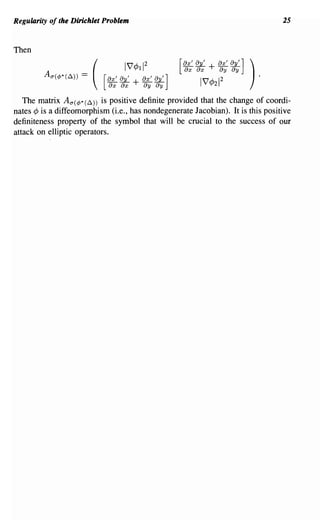

Refer to Figure 1.3. Let W be a collared neighborhood of au. Set au' ==

aw n U and let aD' == ¢(aU'). Define B to be the region bounded by aD](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/partialdifferentialequationsandcomplexanalysis-121120212851-phpapp02/85/Partial-differential-equations-and-complex-analysis-32-320.jpg)

![22 The Dirichlet Problem in the Complex Plane

and aD'. We solve the Dirichlet problem on B with boundary data

I if (E aD

f(() ={ 0 if (E aD'.

Call the solution u.

Consider v == u 0 ¢ : U ~ nt Then, of course, v is still hannonic. By

Caratheodory's theorem, v extends to au, au', and

I if (E au

v == { 0 if (E au'.

Suppose that we knew that solutions of the Dirichlet problem on a smoothly

bounded domain with Coo data are in fact Coo on the closure of the domain.

Then, if we consider a first-order derivative V of v, we obtain

IVvl == IV(u 0 ¢)I == l7ull7¢1 ~ C.

It follows that

(1.5.2)

This will prove to be a useful estimate once we take advantage of the following

lemma.

LEMMA 1.5.3 HOPF'S LEMMA

Let n cc }RN have C 2 boundary. Let u E C(n) with u harmonic and noncon-

stant on n. Let PEn and assume that u takes a local minimum at P. Then

the one-sided normal derivative satisfies

au

av (P) < O.

PROOF Suppose without loss of generality that u > 0 on n near P and that

n

u(P) == O. Let B R be a ball that is internally tangent to at P. We may assume

that the center of this ball is at the origin and that P has coordinates (R, 0, ... ,0).

Then, by Harnack's inequality (see [KR1]), we have for 0 < r < R that

R2 - r 2

u(r, 0, ... , 0) ~ c· R2 + r 2 '

hence

u(r,O, ... ,O)-u(R,O, ... ,O) , 0

- - - - - - - - - - - < -c < .

r-R -

Therefore

ou() ,

ov p ~ -c < o.

This is the desired result. I](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/partialdifferentialequationsandcomplexanalysis-121120212851-phpapp02/85/Partial-differential-equations-and-complex-analysis-33-320.jpg)

![Regularity of the Dirichlet Problem 23

Now let us return to the u from the Dirichlet problem that we considered

prior to line (1.5.2). Hopf's lemma tells us that l7ul 2 c' > 0 near aD. Thus,

from (1.5.2), we conclude that

17¢1 ~ C. (1.5.4)

Thus we have bounds on the first derivatives of ¢.

To control the second derivatives, we calculate that

C 2 17 2 vl == 17(7v) 1== 17(7(u 0 ¢))I

== 1 (7 u ( ¢) . 7¢)1== 1(7 2U . [7¢] 2 ) + (7 u . 7 2 ¢)

7 I·

Here the reader should think of 7 as representing a generic first derivative and

72 a generic second derivative. We conclude that

Hence (again using Hopf's lemma),

17 2 "'1 <

f' -

~

l7ul

< C".

-

In the same fashion, we may prove that l7 k ¢1 ~ Ck , any k E {1,2, ...}. This

means (use the fundamental theorem of calculus) that ¢ E Coo (0).

We have amved at the following situation: Smoothness to the boundary

of confonnal maps implies regularity of the Dirichlet problem on a smoothly

bounded domain. Conversely, regularity of the Dirichlet problem can be used,

together with Hopf's lemma, to prove the smoothness to the boundary of con-

formal mappings. We must find a way out of this impasse.

Our solution to the problem posed in the last paragraph will be to study the

Dirichlet problem for a more general class of operators that is invariant under

smooth changes of coordinates. We will study these operators by (i) localizing

the problem and (ii) mapping the smooth domain under a diffeomorphism to

an upper half-space. It will tum out that elliptic operators are invariant under

these operations. We shall then use the calculus of pseudodifferential operators

to prove local boundary regularity for elliptic operators.

There is an important point implicit in our discussion that deserves to be

brought into the foreground. The Laplacian is invariant under conformal trans-

formations (exercise). This observation was useful in setting up the discussion

in the present section. But it turned out to be a point of view that is too narrow:

we found ourselves in a situation of circular reasoning. We shall thus expand

to a wider universe in which our operators are invariant under diffeomorphisms.

This type of invariance will give us more flexibility and more power.

Let us conclude this section by exploring how the Laplacian behaves under

a diffeomorphic change of coordinates. For simplicity, we restrict attention to](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/partialdifferentialequationsandcomplexanalysis-121120212851-phpapp02/85/Partial-differential-equations-and-complex-analysis-34-320.jpg)

![24 The Dirichlet Problem in the Complex Plane

]R2 with coordinates (x, y). Let

¢ ( x, y) == (¢ 1 (x, y), cP2 (x, y)) == (x', y')

be a diffeomorphism of }R2. Let

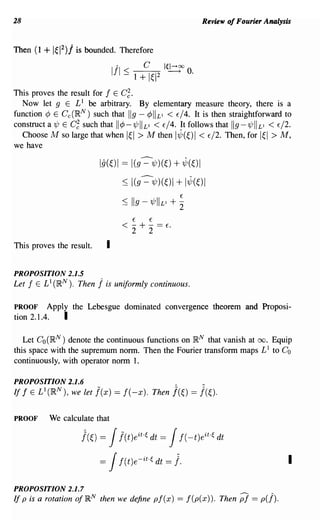

In (x', y') coordinates, the operator ~ becomes

In an effort to see what the new operator has in common with the old one, we

introduce the notation

where

a a a a

axO: axr 1 ax~2 ... ax~n

is a differential monomial. Its "symbol" (for more on this, see the next two

chapters) is defined to be

The symbol of the Laplacian ~ == (a 2 / ax 2 ) + (a 2 / ay2) is

(J(~) == ~f + ~i·

Now associate to (J(~) a matrix ..4~ == (aij)1:S;i,j:S;2, where aij = aij(x) is the

coefficient of ~i~j in the symbol. Thus

The symbol of the transfonned Laplacian (in the new coordinates) is

(J(¢*(~)) == 17¢112~f + 17¢212~i

ax' ay' ax' ay,]

+2 [ - - + - - ~le2

ax ay By By

+ (lower order tenns).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/partialdifferentialequationsandcomplexanalysis-121120212851-phpapp02/85/Partial-differential-equations-and-complex-analysis-35-320.jpg)

![2

Review of Fourier Analysis

2.1 The Fourier Transform

A thorough treatment of Fourier analysis in Euclidean space may be found in

[STW] or [HOR4]. Here we give a sketch of the theory.

If t, ~ E }RN then we let

t· ~ == tl~1 + ... + tN~N.

We define the Fourier transform of an f E £1 (I~N) by

j(~) = Jf(t)eit.~ dt.

Many references will insert a factor of 271" in the exponential or in the measure.

Others will insert a minus sign in the exponent. There is no agreement on this

matter. We have opted for this definition because of its simplicity. We note that

the significance of the exponentials eit.~ is that the only continuous multiplicative

homomorphisms of}RN into the circle group are the functions ¢~ (t) == eit.~.

(We leave this as an exercise for the reader. A thorough discussion appears

in [KAT] or [BAC].) These functions are called the characters of the additive

group }RN.

Basic Properties of the Fourier Transform

PROPOSITION 2.1.1

If f E £1 (}RN) then

PROOF Observe that

Ij(~) I ::; J If(t)1 dt. I](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/partialdifferentialequationsandcomplexanalysis-121120212851-phpapp02/85/Partial-differential-equations-and-complex-analysis-37-320.jpg)

J (pf)(t)eif,.t dt = J f(p(t))eif,.t dt

(s=g,(t)) J f(s)e i f,.p-'(s) ds =J f(s)eip(f,).s ds

(p(j)) (~). I

PROPOSITION 2.1.8

We have

PROOF We calculate that

PROPOSITION 2.1.9

If 8 > 0 and f E L 1(IR N ), then we set 08f(x)

8- N f(x/8). Then

(alif) = ali (I)

0 8f == 08j.

PROOF We calculate that

(alif) = J(ali/) (t)eit.f, dt = J f(8t)e it .f, dt

= J f(t) ei(t/li)-f, 8- N dt = 8- N j(E,/8) = ali(j).

That proves the first assertion. The proof of the second is similar. I

If I, g are L 1 functions, then we define their convolution to be the function

f * g(x) = J f(x - t)g(t) dt = J g(x - t)f(t) dt.

It is a standard result of measure theory (see [RUD3]) that I *g so defined is

an L 1 function and III * gllL1 ::; IIfllL1 IIgllLI.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/partialdifferentialequationsandcomplexanalysis-121120212851-phpapp02/85/Partial-differential-equations-and-complex-analysis-40-320.jpg)

![The Fourier Transform 31

PROOF It is enough to do the case N == 1. Set I == J~oo e- t2 dt. Then

I "I = I: I: e-

s2

ds e-

t2

dt = II

IR2

e-!(s,t)!2 dsdt

{21r roo _r 2

= Jo Jo e rdrd()=7L

Thus I == ~, as desired. I

REMARK Although this is the most common method for evaluating J e- 1x !2 dx,

several other approaches are provided in [HEI]. I

Now let us calculate the Fourier transform of e- 1xI2 • It suffices to treat the

one-dimensional case because

(e- 1xI2 f = IN e-lx!2eixof, dx = l e-x~eixlf,1 dX"""l e-x~eixNf,N dXN"

Now when N == 1 we have

l e-

x2 ix

+ f, dx =l e(f,/2+ix)2 e-e/ 4 dx

= e-e /4l e(f,/2+ix)2 dx

== e-~2 /4 { e(~/2+ix/2)2 ~ dx

J

IR 2

== ~e-~2 /4 1 e(Z/2)2 dz. (2.1.12.1)

2 Jr

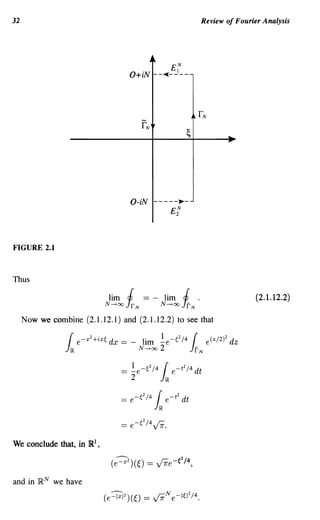

Here, for ~ E R fixed, r == r ~ is the curve t ~ ~ + it. Let r N be the part of

the curve between t == - Nand t == N. Since Ir

== limN ---l>OO Jr N' it is enough

J

for us to understand r N' Refer to Figure 2.1.

Now

Therefore

But, as N -+ 00,

1 +1 -+ O.

JEfl JEr](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/partialdifferentialequationsandcomplexanalysis-121120212851-phpapp02/85/Partial-differential-equations-and-complex-analysis-42-320.jpg)

![The Fourier Transform 33

It is often convenient to scale this formula and write

The function G(x) == (27r)-N/2 e- 1 I2 /2 is called the Gauss-Weierstrass ker-

x

nel. It is a summability kernel (see [KAT]) for the Fourier transform. Observe

that G(~) == e-I~12 /2.

On R N we define

Then

-- --

~(~) = (e-'1~12 /2) = (avee-I~12 /2)

= ave [(27r)N/2e-I~12/2]

== E-N/2(27r)N/2e-I~12 /(2E).

Now assume that !, j are in L 1 and are continuous. We apply Proposi-

tion 2.1.11 with 9 == GE ELI. We obtain

Jf~(x) Jj(~)C.(~) d~.

dx =

In other words,

(2.1.13)

Now e-EI~12 /2 - t 1 uniformly on compact sets. Thus J j(~)e-EI~12 d~ -t

J j(~) d~. That takes care of the right-hand side of (2.1.13).

Next observe that

Thus the left side of (2.1.13) equals

(27r)N Jf(x)G,(x) dx = (27r)N J f(O)G,(x) dx

+(27r)N j[f(x) - f(O)JG,(x) dx

-t (27r)N ·1(0).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/partialdifferentialequationsandcomplexanalysis-121120212851-phpapp02/85/Partial-differential-equations-and-complex-analysis-44-320.jpg)

![34 Review of Fourier Analysis

Thus we have evaluated the limits of the left- and right-hand sides of (2.1.13).

We have proved the following theorem.

THEOREM 2.1.14 THE FOURIER INVERSION FORMULA

If !, j E £1 and both are continuous, then

f(O) = (27r)-N Jj(~) d~. (2.1.14.1 )

Of course there is nothing special about the point 0 E R N . We now exploit

the compatibility of the Fourier transform with translations to obtain a more

general formula. First, we define

(Th!)(x) == I(x - h)

for any function I on RN and any h E RN . Then, by a change of variable in

the integral,

T;] == eih.~ j(~).

Now we apply formula (2.1.14.1) in our theorem to T-h/: The result is

or

THEOREM 2.1.15

If I, j E £1 then for any h E R N we have

f(h) = (2JT)-N Jj(~)e-ih.f, d~.

COROLLARY 2.1.16

The Fourier transform is univalent. That is, if I, 9 E £1 and j == 9 then f = 9

almost everywhere.

PROOF Since I - 9 E £1 and j - g == 0 E £1, this is immediate from either

the theorem or (2.1.13). I

Since the Fourier transform is univalent, it is natural to ask whether it is

surjective. We have

PROPOSITION 2.1.17

The operator

is not onto.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/partialdifferentialequationsandcomplexanalysis-121120212851-phpapp02/85/Partial-differential-equations-and-complex-analysis-45-320.jpg)

![The Fourier Transform 35

PROOF Seeking a contradiction, we suppose that the operator is in fact surjec-

tive. Then the open mapping principle guarantees that there is a constant C > 0

such that

IIIIILI :S cllj"L~'

On IR , let g(~) be the characteristic function of the interval [-1, 1]. The in-

I

verse Fourier transform of g is a nonintegrable function. But then {G 1/ j * g}

forms a sequence that is bounded in supremum norm but whose inverse Fourier

transforms are unbounded in £1 norm. That gives the desired contradiction.

I

Plancherel's Formula

PROPOSITION 2.1.18 PLANCHEREL

If I E C~ (IR N ) then

JIj(~)12 d~ = J (21T)N If(xW dx.

PROOF Define g( x) == I * 1E c~ (IRN ). Then

,,~ ,,~ ,,~ .... 2

9 == I . I == I . I == I . f == III . (2.1.18.1)

Now

g(O) = f * 1(0) = J f( -t)!( -t) dt = J f(t)/(t) dt = J 2

If(t)1 dt.

By Fourier inversion and formula (2.1.18.1) we may now conclude that

J If(t)1 2 dt = g(O) = (21T)-N Jg(~) d~ = (27T)-N JIj(~)12 df

That is the desired formula. I

COROLLARY 2.1.19

If f E £2 (IR N ) then the Fourier transform of I can be defined in the following

fashion: Let Ij E C~ satisfy fj -+ I in the £2 topology. It follows from

the proposition that {.fj } is Cauchy in £2. Let g be the £2 limit of this latter

sequence. We set j == g.

It is easy to check that the definition of j given in the corollary is independent

of the choice of sequence Ij E C~ and that

J11(01 d~ 2

= (21T)N J If(xW dx.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/partialdifferentialequationsandcomplexanalysis-121120212851-phpapp02/85/Partial-differential-equations-and-complex-analysis-46-320.jpg)

![36 Review of Fourier Analysis

We now know that the Fourier transform F has the following mapping prop-

erties:

F: £1 ~ LX

F: L 2 ~ £2.

The Riesz-Thorin interpolation theorem (see [STW]) now allows us to conclude

that

F : £P ~ LP' , 1 ~ p ~ 2,

where p' == p/ (p - 1). If p > 2 then F does not map LP into any nice function

space. The precise norm of F on LP has been computed by Beckner [BEC].

Exercises: Restrict attention to dimension 1. Consider the Fourier transform F

as a bounded linear operator on the Hilbert space £2 (IR N ). Prove that the four

roots of unity (suitably scaled) are eigenvalues of F.

Prove that if p(x) is a Hermite polynomial (see [STW], [WHW]), then the

function p(x)e-lxI2/2 is an eigenfunction of F. (Hint: (ix!) == (j)' and == l'

-i~j.)

2.2 Schwartz Distributions

Thorough treatments of distribution theory may be found in [SCH], [HOR4],

[TRE2]. Here we give a quick review.

We define the space of Schwartz functions:

s = {¢ E c oo (IRN ) : Pa,(3(¢) == x~~ Ix

a

(~) (3 ¢(x) I < 00,

0: = (0:1, .. " O:N), {3 = ({31,"" (3N) }.

Observe that e- 1x12 E Sand p(x) . e- 1x12 E S for any polynomial p. Any

derivative of a Schwartz function is still a Schwartz function. The Schwartz

space is obviously a linear space.

It is worth noting that the space of Coo functions with compact support (which

we have been denoting by C~) forms a proper subspace of S. Since as recently

as 1930 there was some doubt as to whether C~ functions are genuine functions

(see [OSG]), it may be worth seeing how to construct elements of this space.

Let the dimension N equal 1. Define

if x ~ 0

if x < o.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/partialdifferentialequationsandcomplexanalysis-121120212851-phpapp02/85/Partial-differential-equations-and-complex-analysis-47-320.jpg)

![Schwartz Distributions 37

Then one checks, using l'Hopital's Rule, that A E Coo (IR). Set

h(x) == A( -x - 1) . A(X + 1) E C~(I~).

I:

Moreover, if we define

g(x) = h(t) dt,

then the function

f(x) == g(x + 2) . g( -x - 2)

lies in C~ and is identically equal to a constant on (-1, 1). Thus we have

constructed a standard "cutoff function" on ~l. On IR N , the function

plays a similar role. '

Exercise: [The Coo Urysohn lemma] Let K and L be disjoint closed sets

in IR N . Prove that there is a Coo function ¢ on IR N such that ¢ == 0 on K and

¢ == 1 on L. (Details of this sort of construction may be found in [HIR].)

The Topology of the Space 5

The functions Pn,(3 are seminorms on 5. A neighborhood basis of 0 for the

corresponding topology on 5 is given by the sets

NE,f,m == {¢: L lal:S€

Pa,(3(¢) < E} .

1.6I:Sm

Exercise: The space 5 cannot be normed.

DEFINITION 2.2.1 A Schwartz distribution Q is a continuous linear functional

on 5. We write Q E 5'.

Examples:

1. If f EL I , then f induces a Schwartz distribution as follows:

S:3 qH--> f </>fdx E C.

We see that this functional is continuous by noticing that

If </>(x)f(x) dxl ::; sup 1</>1· Ilfll£l = C . Po,o(</».](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/partialdifferentialequationsandcomplexanalysis-121120212851-phpapp02/85/Partial-differential-equations-and-complex-analysis-48-320.jpg)

![38 Review of Fourier Analysis

A similar argument shows that any finite Borel measure induces a distri-

bution.

2. Differentiation is a distribution: On R I , for example, we have

5 ::1 ¢ ~ ¢'(O)

satisfies

I¢' (0) 1 ::; sup I¢' (x) I == PO.I (¢).

xElR

3. If f E LP (RN ), 1 :::; p ::; 00, then f induces a distribution:

Tf : S 3 </J f--> J </Jf dx E c.

To see that this functional is bounded, we first notice that

(2.2.2)

where 1/ p + 1/ p' == 1. Now notice that

(1 + Ix IN +I) I¢(x )I ::; C (po,o (¢) + PN + 1,0 ( ¢)) ,

hence

C

I</J(x) I ::; 1 + Ixl N +1 (Po,o( </J) + PN+I,O(</J)) .

Finally,

II</JII Lp f ::; c· [

J(1 + I~IN+I ) P

,

dx

] lip'

. [Po,o(</J) + PN+I,O(</J)] .

As a result, (2.2.2) tells us that

T f ( ¢) ::; ell f II Lp (Po ,0 ( ¢) + PN + I ,0 ( ¢)) .

Algebraic Properties of Distributions

(i) If Q, (3 E 5' then Q+ (3 is defined by (Q + (3) (¢) == Q(¢) + (3( ¢). Clearly

Q + (3 so defined is a Schwartz distribution.

(ii) If Q E 5' and C E C then CQ is defined by (CQ)(¢) == c[Q(¢)]. We see

that CQ E 5'.

(iii) If 1/J E 5 and Q E 5' then define (1/JQ) (¢) == Q(1/J¢). It follows that 1/JQ

is a distribution.

(iv) It is a theorem of Laurent Schwartz (see [SCH]) that there is no contin-

uous operation of multiplication on S'. However, it is a matter of great

interest, especially to mathematical physicists, to have such an operation.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/partialdifferentialequationsandcomplexanalysis-121120212851-phpapp02/85/Partial-differential-equations-and-complex-analysis-49-320.jpg)

![Schwartz Distributions 39

Colombeau [CMB] has developed a substitute operation. We shall say no

more about it here.

(v) Schwartz distributions may be differentiated as follows: If J-l E S' then

(8/ 8x)(3 J-l E S' is defined, for ¢ E S, by

Observe that in case the distribution J-l is induced by integration against a

C~ function f, then the definition is compatible with what integration by

parts would yield.

Let us differentiate the distribution induced by integration against the function

f(x) == Ixl on lIt Now, for ¢ E S,

f'(¢) == - f(¢')

= - [ : f¢' dx

= -100 f(x)¢'(x) dx - [°00 f(x)¢'(x) dx

= _ roo x¢'(x) dx + fO x¢'(x) dx

io -00

00

=- [x¢(x)]: + 1 ¢(x) dx + [x¢(x)]~oo - [°00 ¢(x) dx

= roo ¢(x) dx _ fO ¢(x) dx.

io -00

Thus f' consists of integration against b( x) == -x (-00,0] + X[O,oo). This function

is often called the Heaviside function.

Exercise: Let n ~

R N be a smoothly bounded domain. Let v be the unit

outward normal vector field to 8n. Prove that -VXn E S'. (Hint: Use Green's

theorem. It will tum out that (- VXn) (¢) == Jan ¢ da, where da is area measure

on the boundary.)

The Fourier Transform

The principal importance of the Schwartz distributions as opposed to other dis-

tribution theories (more on those below) is that they are well behaved under the

Fourier transform. First we need a lemma:](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/partialdifferentialequationsandcomplexanalysis-121120212851-phpapp02/85/Partial-differential-equations-and-complex-analysis-50-320.jpg)

![42 Review of Fourier Analysis

THEOREM 2.2.6 STRUCTURE THEOREM FOR V'

flu E V' then

k

U == LDjJ-lj,

j=1

where J-lj is a finite Borel measure and each Dj is a differential monomial.

IDEA OF PROOF For simplicity, restrict attention to R I . We know that the

dual of the continuous functions with compact support is the space of finite

Borel measures. In a natural fashion, the space of C I functions with compact

support can be identified with a subspace of the set of ordered pairs of Ce

functions: f +-+ (I, f'). Then every functional on C~ extends, by the Hahn-

Banach theorem, to a functional on C e x C e . But such a functional will be

given by a pair of measures. Combining this information with the definition

of derivative of a distribution gives that an element of the dual of C~ is of the

form J-l1 + (J-l2)'. In a similar fashion, one can prove that an element of the dual

of C~ must have the form J-li + (J-l2)' + ... + (J-lk+I)(k).

Finally, it is necessary to note that V' is nothing other than the countable

union of the dual spaces (C~)'. I

The theorem makes explicit the fact that an element of V' can depend on

only finitely many derivatives of the testing function-that is, on finitely many

of the norms Pn,(3.

We have already noted that the Schwartz distributions are the most convenient

for Fourier transform theory. But the space V' is often more convenient in the

theory of partial differential equations (because of the control on the support

of testing functions). It will sometimes be necessary to pass back and forth

between the two theories. In any given context, no confusion should result.

Exercise: Use the Paley-Wiener theorem (discussed in Section 4) or some other

technique to prove that if cP E V then ¢ (j. V. (This fact is often referred to as

the Heisenberg uncertainty principle. In fact, it has a number of qualitative and

quantitative formulations that are useful in quantum mechanics. See [FEG] for

more on these matters.)

More on the Topology of V and V'

We say that a sequence {cPj} ~ V converges to ¢ E V if

1. all the functions ¢j have compact support in a single compact set K o;

2. PK,n(¢j - ¢) -+ 0 for each compact set K and for every multiindex Q.

I

The enemy here is the example of the "gliding hump": On R , if 'ljJ is a

fixed Coo function and ¢j (x) == 'ljJ (x - j), then we do not want to say that the

sequence {¢j} converges to O.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/partialdifferentialequationsandcomplexanalysis-121120212851-phpapp02/85/Partial-differential-equations-and-complex-analysis-53-320.jpg)

![44 Review of Fourier Analysis

PROOF We calculate that

(a * g)(cP) = a(§ * cP) = aX [1 §(x - t)cP(t) dt] .

Here the superscript on Q denotes the variable in which Q is acting. This last

Next we introduce the concept of Friedrichs mollifiers. Let ¢ E C~ be

supported in the ball B (0, 1). For convenience we assume that ¢ 2: 0, although

this is not crucial to the theory. Assume that J ¢( x) dx == 1. Set ¢E (x) ==

N

E- ¢(x/ E).

The family {¢E} will be called a family of Friedrichs mollifiers in honor of

K. O. Friedrichs. The use of such families to approximate a given function

by smooth functions has become a pervasive technique in modem analysis. In

functional analysis, such a family is sometimes called a weak approximation to

the identity (for reasons that we are about to see). Observe that J ¢E (x) dx == 1

for every E > O.

LEMMA 2.3.3

If f E LP(RN ), 1~p ~ 00, then

PROOF The case p == 00 is obvious, so we shall assume that 1 :::; p < 00.

Then we may apply Jensen's inequality, with the unit mass measure ¢E(X) dx,

to see that

Ilf*cP,II1p = 111 P

f(x-t)cP,(t)dtI dx

:=; 1

1 If(x - t)IPlcP,(t)1 dt dx

= 11 If(x - t)IP dx cP,(t) dt

= 1IlflltpcP,(t) dt

== 11111~p· I

REMARK The function IE == f * ¢E is certainly Coo Gust differentiate under

the integral sign) but it is generally not compactly supported unless I is. I](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/partialdifferentialequationsandcomplexanalysis-121120212851-phpapp02/85/Partial-differential-equations-and-complex-analysis-55-320.jpg)

![Convolution and Friedrichs Mollijiers 45

LEMMA 2.3.4

For 1 :::; p < 00 we have

PROOF We will use the following claim: For 1 :::; p < 00 we have

where 7ft f (x) == ! (x - h). Assume the claim for the moment.

Now

II!< - !11~p 111 !(x - t)¢«t) dt - 1!(x)¢«t) dtl[

111[!(x - t) - f(x)]¢«t) dtl[

111[Ttf(x) - f(x)]¢«t) dtl[

< 1IITt! - fll~p¢«t) dt

(t=J-U)

== 1II -! liP ()

TJi,E! LP¢ J-l dJ-l.

In the inequality here we have used Jensen's inequality. Now the claim and the

Lebesgue dominated convergence theorem yield that lifE - fllLP -+ O.

To prove the claim, first observe that if 1/J E GYe then I Th1/J - 1/J I sup -+ 0

by uniform continuity. It follows that II Th 1/J - 1/J II Lp -+ O. Now if ! E LP is

arbitrary and E > 0, then choose 1/J E Ce such that II! - 1/J II Lp < E/2. Then

lim sup II Thf - !IILP :::; lim sup II Th(! -1/J)IILP + lim sup IITh1/J -1/JII :::; E.

h---+O h---+O h---+O

Since E > 0 was arbitrary, the claim follows. I

LEMMA 2.3.5

If ! E C e then fE -+ ! uniformly.

PROOF Let 1] > 0 and choose E > 0 such that if Ix-yl < E then If(x)- f(y)1 <

1]. Then

If«x) - !(x)1 11 f(x - t)¢«t) dt - !(x)1

=

= I/[f(x - t) - f(x)J¢«t) dtl](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/partialdifferentialequationsandcomplexanalysis-121120212851-phpapp02/85/Partial-differential-equations-and-complex-analysis-56-320.jpg)

![46 Review of Fourier Analysis

:; r J1tl$.E

Ij(x-t)-j(x)I¢«t)dt

::; / ry¢< (t) dt

== 1].

That completes the proof. I

Exercise: Is the last lemma true for a broader class of /? Prove that if

f E C~(IRN), then lifE - flick - t O.

Now if Q E V' and cPE is a family of Fredrichs mollifiers, then we define

o:«x) == 0: * cP«x) = o:(¢«x - .)) = 0: ('L:i<) .

LEMMA 2.3.6

Each QE is a Coo function. Moreover, Q E -t Q in the topology of V'.

PROOF For simplicity of notation, we restrict attention to dimension one. First

let us see that Q E is differentiable on R We calculate:

Q[cPE(X + h - .)] - Q[cPE(X - .)]

h

= 0: ( ¢< (x +h -1- cP< (x - .)) . (2.3.6.1)

Observe that

cP«x + h -1- ¢«x - .) _ ¢:(x _ .)

in the topology of V. Thus (2.3.6.1) implies that

0:< (x + h~ - o:«x) _ o:(cP:(x _ .))

as h - t O.

Now let us verify the convergence of Q E to Q. Fix a testing function 'l/J E V.

Then

0:< ( 'ljJ) = / 0:< ( x) 'ljJ (x) dx = / 0:

8

(cP< (x - s)) 'ljJ (x) dx

= 0:

8

[/ (¢«x - s)) 'ljJ(x) dX] = 0: 8

[/ (¢«x)) 'ljJ(x + s) dX]

= 0:

8

[/ ¢< ( -x )'ljJ( S - x) dX] . (2.3.6.2)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/partialdifferentialequationsandcomplexanalysis-121120212851-phpapp02/85/Partial-differential-equations-and-complex-analysis-57-320.jpg)

![48 Review of Fourier Analysis

To see this, let ¢ E V. Then

REMARK If a E V' is compactly supported and 'l/J E £, then we can define

Q( 'l/J) in the following manner: Let supp Q ~ K a compact set. Let <I> E C~

be identically equal to 1 on K. Then we set Q ( 'l/J) == Q (<I> . 'l/J). I

Now let us use (2.3.8) to see that & is Coo when Q E V' is compactly

supported. For simplicity, we assume that the dimension is one. Then

Notice that we may pass the limit inside the brackets because the Newton quo-

tients converge in C k for every k on the support of Q. Thus we have shown

that & is differentiable. Iteration of this argument shows that & is Coo. We

shall learn in the next section that, in fact, the Fourier transform of a compactly

supported distribution is real analytic.

We conclude with a remark on how to identify a smooth distribution. The

spirit of this remark will be a recurring theme throughout this book. We ac-

complish this identification by examining the decay of & at infinity. Namely, let

¢ E C~ be such that ¢ == 1 on a large compact set. We write & == ¢& +(1- ¢ )&.

Applying the inverse Fourier transform (denoted by ---), we see that

Then, since (¢&) is compactly supported, the first term is a Coo function. We

conclude that, in order to see whether Q is Coo, we must examine (( 1 - ¢) &)".

But this says, in effect, that we must examine the behavior of & at infinity.

2.4 The Paley-Wiener Theorem

We begin by examining the so-called Fourier-Laplace transform. If f E C~ (I~N )

and ( == ~ + if] E ]RN + ilRN ~ eN, then we define

j(() = r

J~N

!(x)e ix -( dx.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/partialdifferentialequationsandcomplexanalysis-121120212851-phpapp02/85/Partial-differential-equations-and-complex-analysis-59-320.jpg)

![leVleW oJ ~"ourier Analysis

for some C, K. As a result,

I&(()I == IQX(eix'()1 == IQx (¢((x))1

:S C L sup IDJ3¢(1

1J3I~K B(O,A)

:S C(I(I + I)K sup le ix .( I

xEB(O,A)

Next let us assume that Q is a C~ function supported in B(O, A). We shall

prove (2.4.1.2). Now

I&(()I = If a(x)e ix -<: dxl

::: r la(x)leA11m(1 dx

JB(O,A)

:S IIQIILle A1Im (l.

This is (2.4.1.2) with K == 0. To obtain (2.4.1.2) with K == 1 we write, for

(j i= 0,

I&(()I = If a(x)e

ix

-<: dxl

== Ifa(x)~~eix,(

Z(j aXj

dxl

= I :j f (&~j a(x)) eix .( dxl

:S _1 II~QII eA11m(l.

I(jl aXj Ll

We can iterate this argument to obtain (2.4.1.2) for every K.

Next we prove that if (2.4.1.2) holds then Q is a C~ function with support

in B(O, A). We write

la(x)1 = I(27r)-N f U(~)e-ix,~ d~1

= I(27r)-N JU(~ + i1])e-ix.(~+i'7) d~l·](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/partialdifferentialequationsandcomplexanalysis-121120212851-phpapp02/85/Partial-differential-equations-and-complex-analysis-61-320.jpg)

![Introduction to Pseudodifferential Operators 53

Ehrenpreiss and Malgrange, among others. The approach of Ehrenpreiss was to

write

u(x) = c· Ju(~)e-ix.~ d~ = J-1;1 j(~)e-ix,~ ~. 2

Using Cauchy theory, he was able to relate this last integral to

J- + I~

1.

~1712

j(~ + i1])e- ix '(U i7]) d~.

In this way he avoided the singularity at ~ == 0 of the right-hand side of (3.1.2).

Malgrange's method, by contrast, was to first study (3.1.1) for those f such

that j vanishes to some finite order at 0 and then to apply some functional

analysis.

We have already noticed that, for the study of Coo regularity, the behavior

of the Fourier transform on the finite part of space is of no interest. Thus

the philosophy of pseudodifferential operator theory is to replace the Fourier

multiplier 1/1~12 by the multiplier (1 - ¢(~))/1~12, where ¢ E C~(IRN) is

identically equal to 1 near the origin. Thus we define

for any 9 E C~. Equivalently,

Now we look at u - Pf, where f is the function on the right of (3.1.1):

.-..

(u - P f) == it - P f

1 A 1- ¢(~) A

=-~f+ 1~12 f

== _ ¢(~) fA

1~12 .

Then u - P f is a distribution whose Fourier transform has compact support,

that is, u - P f is Coo. So studying the regularity of u is equivalent to studying

the regularity of P f. This is precisely what we mean when we say that P is a

parametrix for the partial differential operator~. And the point is that P has

symbol - (1 - ¢) / 1~12, which is free of singularities.

Now let L be a partial differential operator with (smooth) variable coefficients:

The classical approach to studying such operators was to reduce to the constant](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/partialdifferentialequationsandcomplexanalysis-121120212851-phpapp02/85/Partial-differential-equations-and-complex-analysis-64-320.jpg)

![Introduction to Pseudodifferential Operators 55

In the constant coefficient case, composition of operators corresponds to multi-

plication of symbols so that we would have

((L 0 T)f) = £(~) . (I ~(;)(~)) j(~)

== (1 - <P(~))j(~).

In the variable coefficient case, we hope for an equation such as this with the

addition of an error.

A calculus of pseudodifferential operators is a collection of integral opera-

tors that contains all elliptic partial differential operators and their parametrices

and such that the collection is closed under composition and the taking of ad-

joints. Once the calculus is in place, then, when one is given a partial or

pseudodifferential operator, one can instantly write down a parametrix and ob-

tain estimates. Pioneers in the development of pseudodifferential operators were

Mikhlin ([MIK1], [MIK2]) and Calderon and Zygmund [CZ2].

One of the classical approaches to developing a calculus of operators finds

it roots in the work of Hadamard [HAD] and Riesz [RIE] and Calderon and

Zygmund [CZ1]. To explain this approach, we introduce two types of integral

operators.

The first are based on the classical Calderon-Zygmund singular integral ker-

nels. Such a kernel is defined to be a function of the form

O(x)

K(x) = Ixl N '

where 0 is a smooth function on }RN {O} that is homogeneous of degree zero

(i.e., O(AX) == O(x) for all A > 0). Then it can be shown (see [STSI]) that the

Cauchy principal value integral

TK f(x) == lim r

E---+O+ J1tl>E

f(x - t)K(t) dt

converges for almost every x when f E LP and that T is a bounded operator

from LP to LP, 1 < p < 00.

The second type of operator is called a Riesz potential. The Riesz potential

of order ex has kernel

0< ex < N,

where CN,Q is a positive constant that will be of no interest here. The Riesz

potentials are sometimes called fractional integration operators because the

Fourier multiplier corresponding to k Qis c~ Q I~I-Q. If we think about the fact

that multiplication on the Fourier transform side by ( -I ~ 1) ex > 0, corresponds

2

Q ,

to applying a power of the Laplacian-that is, it corresponds to differentiation-](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/partialdifferentialequationsandcomplexanalysis-121120212851-phpapp02/85/Partial-differential-equations-and-complex-analysis-66-320.jpg)

![56 PseudodifferentiDl Operators

then it is reasonable that a Fourier multiplier 1~1J3 with (3 < 0 should correspond

to integration of some order.

Now the classical idea of creating a calculus is to consider the smallest algebra

generated by the singular integral operators and the Riesz potentials. Unfortu-

nately, it is not the case that the composition of two singular integrals is a

singular integral, nor is it the case that the composition of a singular integral

and a fractional integral is (in any simple fashion) an operator of one of the com-

ponent types. Thus, while this calculus could be used to solve some problems,

it is rather clumsy.

Here is a second, and rather old, attempt at a calculus of pseudodifferential

operators:

DEFINITION 3.1.1 A function p(x,~) is said to be a symbol of order m if p

is Coo, has compact support in the x variable, and is homogeneous of degree

m in ~ when ~ is large. That is, we assume that there is an M > 0 such that

if I~I > ]v! and A > 1 then

It is possible to show that symbols so defined, and the corresponding operators

form an algebra in a suitable sense. These may be used to study elliptic operators

effectively.

But the definition of symbol that we have just given is needlessly restrictive.

For instance, the symbol of even a constant coefficient partial differential oper-

ator is not generally homogeneous and we would have to deal with only the top

order terms. It was realized in the mid-1960s that homogeneity was superfluous

to the intended applications. The correct point of view is to control the decay

of derivatives of the symbol at infinity. In the next section we shall introduce

the Kohn-Nirenberg approach to pseudodifferential operators.

3.2 A Formal Treatment of Pseudodifferential Operators

Now we give a careful treatment of an algebra of pseudodifferential operators.

We begin with the definition of the symbol classes.

DEFINITION 3.2.1 KOHN-NIRENBERG [KONlj Let m E}R. We say that a

smoothfunction a(x,~) on }RN x}RN is a symbol of order m if there is a compact

set K ~ }RN such that supp a ~ K x}RN and, for any pair of multiindices Q, (3,](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/partialdifferentialequationsandcomplexanalysis-121120212851-phpapp02/85/Partial-differential-equations-and-complex-analysis-67-320.jpg)

![A Formal Treatment of Pseudodifferential Operators 57

there is a constant Cn ,/3 such that

(3.2.1.1)

We write a E sm.

As a simple example, if <I> E C~ (IR N ), <I> == 1 near the origin, define

Then a is a symbol of order m. We leave it as an exercise for the reader to

verify condition (3.2.1.1).

For our purposes, namely the local boundary regularity of the Dirichlet prob-

lem, the Kohn-Nirenberg calculus will be sufficient. We shall study this calculus

in detail. However, we should mention that there are several more general cal-

culi that have become important. Perhaps the most commonly used calculus is

the Hormander calculus [HOR2]. Its symbols are defined as follows:

DEFINITION 3.2.2 Let m E IR and 0 ~ p, 8 ~ 1. We say that a smooth

function a( x,~) lies in the symbol class S;::c5 if

The Kohn-Nirenberg symbols are special cases of the Hormander symbols

with p == 1 and 8 == 0 and with the added convenience of restricting the x

support to be compact. Hormander's calculus is important for the study of the

a-Neumann problem (treated in our Chapter 8). In that context symbols of class

S:/2,1/2 arise naturally.

Even more general classes of operators, which are spatially inhomogenous

and nonisotropic in the phase variable ~, have been developed. Basic references

are [BEF2], [BEA 1], and [HOR5]. Pseudodifferential operators with "rough

symbols" have been studied by Meyer [MEY] and others.

The significance of the index m in the notation sm

is that it tells us how the

corresponding pseudodifferential operator acts on certain function spaces. While

one may formulate results for C k spaces, Lipschitz spaces, and other classes of

functions, we find it most convenient at first to work with the Sobolev spaces.

DEFINITION 3.2.3 If ¢ E V then we define the norm

II¢IIHS = 11¢lls == (/ 1¢(~)12 (1 + 1~12r d~) 1/2 .

We let HSC~N) be the closure of V with respect to II I/s.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/partialdifferentialequationsandcomplexanalysis-121120212851-phpapp02/85/Partial-differential-equations-and-complex-analysis-68-320.jpg)

![A Formal Treatment of Pseudodifferential Operators 59

Our plan is to show that {¢j} is an equibounded, equicontinuous family of

functions. Then the Ascoli-Arzehi theorem [RUD1] will imply that there is a

subsequence converging uniformly on compact sets to a (continuous) function

g. But (3.2.5.1) guarantees that a subsequence of this subsequence converges

pointwise to the function f. So f == 9 almost everywhere and the required

assertion follows.

To see that {¢j} is equibounded, we calculate that

IcPj(x)1 = c ·11 e-ix.F,Jj(~) d~1

~ c· 1IJj(~)1(1 + 1~12)s/2(1 + 1~12)-s/2 d~

~ c· 1IJj(~)12(1 + 1~12)s d~ . 1 + 1~12)-s d~)

( )

1/2 (

(1

1/2

.

Using polar coordinates, we may see easily that, for s > N /2,

Therefore

and {¢ j} is equibounded.

To see that {¢j} is equicontinuous, we write

Observe that le-ix,~ - e-iy·~ I ::; 2 and, by the mean value theorem,

Then, for any 0 < E < 1,

le-ix,~ _ e-iY'~1 == le-ix,~ _ e-iY'~ll-t:le-ix,~ _ e-iY'~It: ::; 21-€lx _ ylt:I~It:.

Therefore

IcPj(x) - cPj(y)1 ~c 1IJj(~)lIx yl'I~I' d~

-

~ C1x - 1IJj(~)1 + 1~12)'/2 d~

yl' (1

~ C1x - yl' IlcPj IIHB ( J(1 + It;Y)-s+, d~ )

1/2

.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/partialdifferentialequationsandcomplexanalysis-121120212851-phpapp02/85/Partial-differential-equations-and-complex-analysis-70-320.jpg)

![62 Pseudodifferential Operators

LEMMA 3.2.8

If P E sm then, for any multiindex a and integer k > 0, we have

Here F x denotes the Fourier transform in the x variable.

PROOF If a is any multiindex and r is any multiindex such that I,I == k, then

1'YIIFx

17 (D~p(x,~)) 1== IFx (D1D~p(x,~)) (1])1

::; IID~+'Yp(x,~)IILI(x) ~ Ck,o:' (1 + 1~I)m.

As a result,

This is what we wished to prove. I

LEMMA 3.2.9

We have that

PROOF Observe that

But then HS and H-s are clearly dual to each other by way of the pairing

(I, g) = Jj(~)g(~) df I

The upshot of the last lemma is that, in order to estimate the H S norm of a

function (or Schwartz distribution) cP, it is enough to prove an inequality of the

form

for every 1/J E V.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/partialdifferentialequationsandcomplexanalysis-121120212851-phpapp02/85/Partial-differential-equations-and-complex-analysis-73-320.jpg)

![A Formal Treatment of Pseudodifferential Operators 63

PROOF OF THEOREM 3.2.6 Fix ¢ E V. Let p E Smand let P = Op(p). Then

PcjJ(x) = 1 O¢(~) d~.

e-ix.€p(x,

Define

SX(A,~) = 1eiX·)o.p(x,~)dx.

This function is well defined since p is compactly supported in x. Then

P¢(1]) = 11 ~)¢(~) d~eiTJ'x

e-ix.€p(x, dx

= 1 ~)¢(~)eix'(TJ-O d~

1 p(x, dx

= 1Sx(1]-~,~)¢(~)df

We want to estimate IIP¢Is-m. By the remarks following Lemma 3.2.9, it is

enough to show that, for 'l/J E V,

We have

11 PcjJ(x)ijj(x) dxl = 11 P¢(~)~(~) d~1

= 11 (1 Sx(~ - 1], 1])¢(1]) d1]) ~(~) d~1

= 1 Sx(~

1 - 1],1])(1 + 11]I)-s(1 + Iw s- m

x ~ ( ~) (1 + 1 1) m - s ¢(17) (1 +

~ 1171) s d 17 d~ .

Define

K(~,1]) = ISx(~ -1],1])(1 + 11]I)-s(1 + Iws-ml·

We claim that

JIK(~, d~ 1])1 :::; C

and

JIK(~,1])1 d1]:::; C.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/partialdifferentialequationsandcomplexanalysis-121120212851-phpapp02/85/Partial-differential-equations-and-complex-analysis-74-320.jpg)

![66 Pseudodifferential Operators

Here D~ == (ia j ax)Q. We shall learn more about asymptotic expansions later.

The basic idea of an asymptotic expansion is that, in a given application, the

asymptotic expansion may be written in more precise form as

One selects k so large that the error term £k is negligible.

If we apply this asymptotic expansion to the operator a(X)ajaxl that was

just considered, it yields that

o-(A*) = i~la(x) - ~a (x),

UXI

which is just what we calculated by hand.

Now let us look at an example to motivate how compositions of pseudodif-

ferential operators will behave. Let the dimension N be 1 and let

d

and B == b(x) dx .

Then a(A) == a(x)( -i~) and a(B) == b(x)( -i~). Moreover, if ¢ E 'D then

(A 0 B)(¢) = (a(x) d~) (b(X) ~~)

Thus we see that

0-( A 0 B) = a(x) ~~ (x) (-i~) + a(x )b(x)( -i~f.

Notice that the principal part of the symbol of A 0 B is

a(x)b(x)( -i~)2 == a(A) . a(B).

In general, the Kohn-Nirenberg formula says (in }RN) that

o-(A 0 B) = L Q

od (a)Q (o-(A)) . D~(o-(B)).

1 fJ~ (3.3.1)

Recall that the commutator, or bracket, of two operators is

[A,B] == AB - BA.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/partialdifferentialequationsandcomplexanalysis-121120212851-phpapp02/85/Partial-differential-equations-and-complex-analysis-77-320.jpg)

![The Calculus of Pseudodifferential Operators 67

Here juxtaposition of operators denotes composition. A corollary of the Kohn-

Nirenberg formula is that

a([A, B]) = L (8/8~Y>a(A)D~a(B) -, (8/80aa(B)D~a(A)

Q.

Inl>O

(notice here that the Q == 0 term cancels out) so that a([A, B]) has order strictly

less than (order(A) + order(B)). This phenomenon is illustrated concretely in

JRl by the operators A == a(x)d/dx, B == b(x)d/dx. One calculates that

db da) d

AB - BA == ( a(x) dx (x) - b(x) dx (x) dx'

which has order one instead of two.

Our final key result in the development of pseudodifferential operators is the

asymptotic expansion for a symbol. We shall first have to digress a bit on the

subject of asymptotic expansions.

Let f be a Coo function defined in a neighborhood of 0 in R Then

00 1 dn f

f(x) r-..J " -(0) x n .

- (3.3.2)

L..-i n! dx n

o

We are certainly not asserting that the Taylor expansion of an arbitrary Coo func-

tion converges back to the function, or even that it converges at all (generically

just the opposite is true).

This formal expression (3.3.2) means instead the following: Given an N > 0

there exists an M > 0 such that whenever m > M and x is small then the

partial sum Sm satisfies

Now we present a notion of asymptotic expansion that is related to this one,

but is specially adapted to the theory of pseudodifferential operators:

DEFINITION 3.3.3 Let {aj} be symbols in UmS m . We say that another symbol

a satisfies

if for every L E jR+ there is an M E Z+ such that

M

a - Laj E S-L.

j=l](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/partialdifferentialequationsandcomplexanalysis-121120212851-phpapp02/85/Partial-differential-equations-and-complex-analysis-78-320.jpg)

![The Calculus of Pseudodifferential Operators 69

Notice that the integral is not absolutely convergent and must therefore be in-

terpreted as an iterated integral.

PROPOSITION 3.3.7

Let r E T m have x- and y-supports contained in a compact set K. Then

the operator R defined as in (3.3.6) defines a pseudodifferential operator of

Kohn-Nirenberg type with symbol pEW K having an asymptotic expansion

p(x,~) '" L ~!alD~r(x,~,y)ly=x'

n

PROOF We calculate that

JeiY'~r(x, ~,y )¢>(y) dy = (r(x, ~, .)¢>(-))

= (i3 (x, y, .) * J(-)) (~).

Here f3 indicates that we have taken the Fourier transform of r in the third

variable. By the definition of R¢ we have

R¢>(x) = JJei(-x+Y)'~r(x,~,y)¢>(y)dyd~

J

= e-ix.~ [i3(x,~,.) * J(-)] (~) d~

= JJi3(x,~, ~ - TJ)J(TJ) dTJe-ix,~ d~

= JJi3(x,~, ~ - TJ)e-ix,(~-'f}) d~J(TJ)e-ix.'f} dT]

== J p(x, y)J(TJ)e-ix.'f} dTJ·

Here

Ji3(x,~, ~ TJ)e-ix(~-'f}) ~

p(x, TJ) == -

=Je-ix'~i3(x, ~ + TJ,~) d~.

Now if we expand the function f3 (x, TJ + .,~) in a Taylor expansion in powers

of ~, it is immediate that p has the claimed asymptotic expansion. In particular,

one sees that p E sm. In detail, we have

i3(x, 1] +~,~) = L a;i3(x, TJ,~) ~~ + R.

Inl<k](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/partialdifferentialequationsandcomplexanalysis-121120212851-phpapp02/85/Partial-differential-equations-and-complex-analysis-80-320.jpg)

![70 Pseudodifferential Operators

Thus (dropping the ubiquitous c from the Fourier integrals),

p(x,Tj) = L 1e-iX'€8;f3(x,Tj,~):~ d~ + 1Rd~

lal<k

= L ~!8;D~r(X,Tj,y)ly=x + 1 Rd~.

lal<k

The rest is formal checking. I

PROOF OF THEOREM 3.3.5 Let pEW K n sm

and choose cP, 1/J E V. Then,

with P the pseudodifferential operator corresponding to the symbol p, we have

(dJ, P* 1/J) == (PcP, 1/J)

= 1[1 e-iX'€p(X,~)¢(~)d~] "j;(x)dx

= 1 1e-i(x-YH4>(y)dyp(x,~)d~"j;(x)dx.

1

Let us suppose for the moment that p is compactly supported in~. With this

extra hypothesis the integral is absolutely convergent and we may write

(4), P*7/J) = 14>(Y) [11 ei(x-y)·€ p(x, ~)7/J(x) d~ dx ] dy. (3.3.5.1)

Thus we have

P*7/J(y) = 1 ei(x-YHp(x,~)7/J(x)d~dx.

1

Now let p E C~ be a real-valued function such that p == 1 on K. Set

r(x,~,y) == p(x)· p(y,~).

Then

P*7/J(y) =11 ~)p(Y)7/J(x) d~

ei(x-YH p(x, dx

=1ei(x-YHr(y,~,x)7/J(x)d~dx

== R1/J(y),

where we define R by means of the multiple symbol r. (Note that the roles of

x and y here have unfortunately been reversed.)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/partialdifferentialequationsandcomplexanalysis-121120212851-phpapp02/85/Partial-differential-equations-and-complex-analysis-81-320.jpg)

![The Calculus of Pseudodifferential Operators 71

By Proposition 3.3.7, P* is then a classical pseudodifferential operator with

symbol p* whose asymptotic expansion is

p*(x,~) '" ~ ~! of D; [p(x)p(y, ~)] Iy=x

'" L J,af D';p(x, ~).

Q.

a

We have used here the fact that p == 1 on K. The theorem is thus proved with

the extra hypothesis of compact support of the symbol in ~.

To remove the extra hypothesis, let ¢ E ergo satisfy ¢ == 1 if I~ I ~ 1 and

¢ == 0 if I~I 2: 2. Let

Observe that Pj ~ P in the e k topology on compact sets for any k. Also, by

the special case of the theorem already proved,

The proof is completed now by letting j ~ 00. I

THEOREM 3.3.8 KOHN-NIRENBERG

Let P E l1 K n sm, q E l1 K n sn. Let P, Q denote the pseudodifferential

operators associated with p, q respectively. Then Po Q == Op(a) where

1. a E l1 K n sm+n;

2. a ~ La ~8rp(x, ~)D~q(x, ~).

PROOF We may shorten the proof by using the following trick: write Q =

(Q*) * and recall that Q* is defined by

Q*¢J(y) = / / ei(x-YH¢J(x)q(x,~)dxd(,

= (/ eix'~¢J(x)q(x,~) dx ) ---- (y).

Here we have used (3.3.5.1).

Then

Q¢J(x) = (J eiY·~¢J(y)q.(y,~) dy) ---- (x), (3.3.8.1 )](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/partialdifferentialequationsandcomplexanalysis-121120212851-phpapp02/85/Partial-differential-equations-and-complex-analysis-82-320.jpg)

![72 Pseudodifferential Operators

where q* is the symbol of Q*. (Note that q* is not if; however, we do know

that if is the principal part of q*.) Then, using (3.3.8.1), we may calculate that

(P 0 Q)(¢»(x) = J e-ix·ep(x, ~)(Q¢)(O d~

= JJe-ix·ep(x,Oeiy·eq*(y,~)¢>(y)dyd~

= JJe-i(x-y)·e [p(x,~)q*(y,~)] ¢>(y)dyd~.

Set q == q*. Define

r(x,~, y) == p(x,~) . ij(y, ~).

One verifies directly that r E Tn+m. We leave this as an exercise. Thus R,

the associated operator, equals P 0 Q. By Proposition 3.3.7 there is a classical

symbol a such that R == Op( a) and

a(x,O "-J L ~! of D~r(x,~, y)ly=x'

Q

Developing this last line we obtain

a(x,O "-J L ~!OfD~ (p(x,Oq(y,~))ly=x

Q

"-J L ~!Of [p(x,OD~q(y,O] Iy=x

Q

"-J L ~or [p(x,OD~q(x,O]

o.

Q

"-J L all! [or1p(x,o] a;! [otD~2D~lq(X,~)]

QI,Q2

QI

'""" oI! 8 ~ p ( x, ~ ) D x

~ 1 ~ 0 1 ! 8Q2 D x q x, ~ ) ]

2 ~

QI ['""" Q2 _(

f"V

QI Q2

"-J L ~o{p(X,~)D~lq(X,~).

0'.

QI](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/partialdifferentialequationsandcomplexanalysis-121120212851-phpapp02/85/Partial-differential-equations-and-complex-analysis-83-320.jpg)

![The Calculus of Pseudodifferential Operators 73

Here we have used the fact that the expression inside the brackets is just the

asymptotic expansion for the symbol of (Q*) *. That completes the proof. I

The next proposition is a useful device for building pseudodifferential oper-

ators. Before we can state it we need a piece of terminology: we say that two

pseudodifferential operators P and Q are equal up to a smoothing operator if

P - Q E Sk for all k < O. In this circumstance we write P rv Q.

PROPOSITION 3.3.9

Let Pj, j == 0, 1,2, ..., be symbols of order mj, mj ~ -00. Then there is a

symbol P E smo, unique modulo smoothing operators, such that

PROOF Let 'l/J : ~n ~ [0, 1] be a Coo function such that 'l/J == 0 when Ixl ::; 1

and 'l/J == 1 when Ixl 2: 2. Let 1 < t l < t2 < ... be a sequence of positive

numbers that increases to infinity. We will specify these numbers later. Define

00

p(x,~) == L 'l/J(~/tj )Pj (x, ~).

j=O

Note that for every fixed x, ~ the sum is finite, for 'l/J (~/ tj) == 0 as soon as

tj> I~I. Thus P is a well-defined Coo function.

Our goal is to choose the tj'S so that P has the correct asymptotic expansion.

We claim that there exist {t j} such that

Assume the claim for the moment. Then for any multiindices Q, {3 we have

00

ID~Drp(x,~)1 ::; L ID~Dr ('l/J(~/tj)Pj(x,~))1

j=O

00

::; L2- (1 + 1~l)mJ-IQI

j

j=O](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/partialdifferentialequationsandcomplexanalysis-121120212851-phpapp02/85/Partial-differential-equations-and-complex-analysis-84-320.jpg)

![74 Pseudodifferential Operators

It follows that p E sm

o• Now we want to show that p has the right asymptotic

°

expansion. Let < k E Z be fixed. We will show that

k-l

p- LPj

j=O

lives in smk. We have

k-l

- L (l-7/J(~/tj))Pj(x,~)

j=O

== q(x,~) + s(x, ~).

It follows directly from our construction that q(x,~) E k

sm

• Since [l-'ljJ(~/tj)]

has compact support in B(O, 2t l ) for every j, it follows that s(x,~) E S-oo.

Then

k-l

P - LPj E sm k

j=O

as we asserted.

We wish to see that P is unique modulo smoothing terms. Suppose that

qE smo and q L~OPj. Then

f"V

P- q== (p - LPj) - (q - LPj)

J<k J<k

for any k. That establishes the uniqueness.

It remains to prove the claim. First observe that, for lad == j,

IDf7/J(~/tQ)1 = ik I(Df7/J) (~/tj)1

t·

J

+

~ tjl I1€1::;2t

sup

J