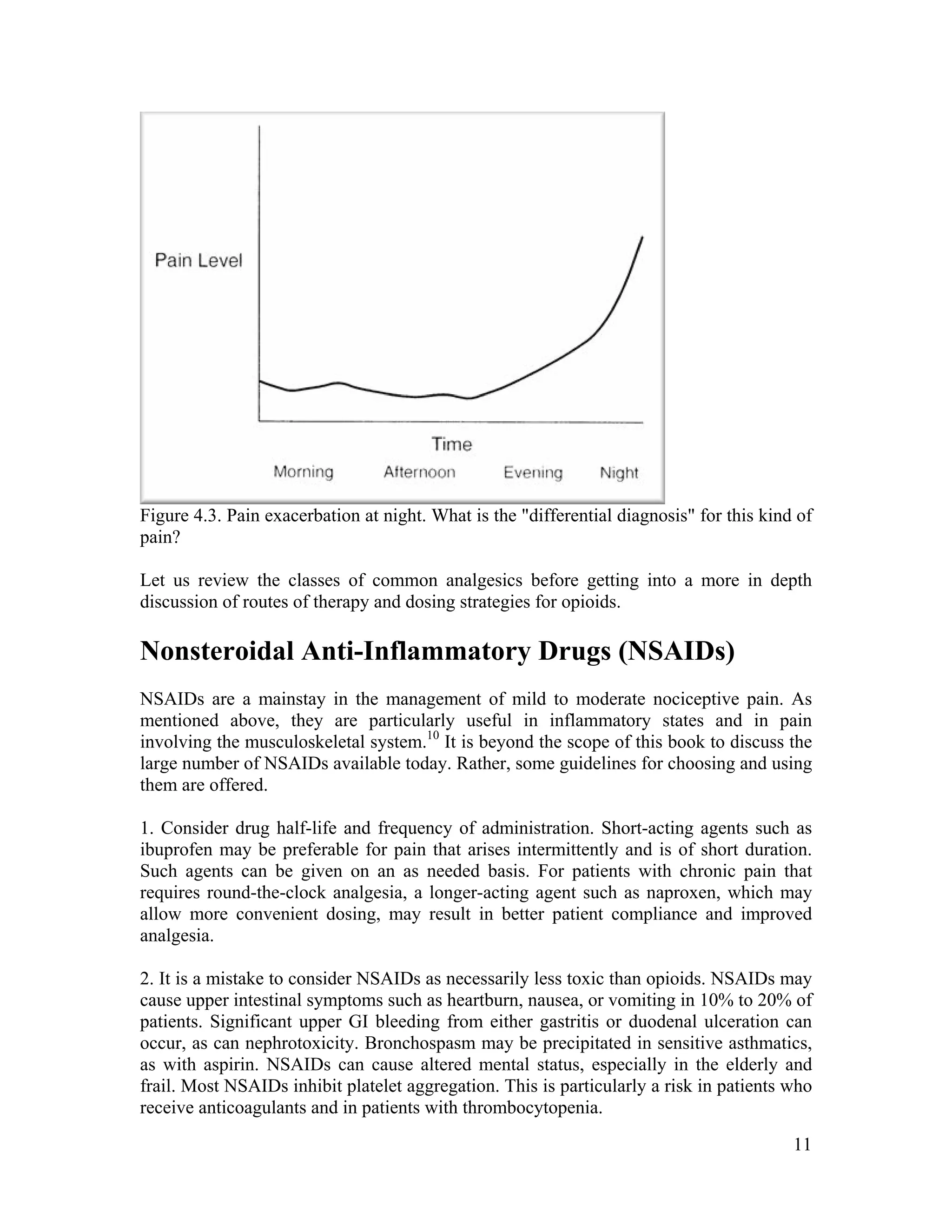

The document discusses the differences between acute and chronic pain, highlighting that acute pain serves a clear biological purpose and is easier to recognize and treat, while chronic pain is complex, often coexisting with depression, and lacks obvious physical signs. It emphasizes the importance of using pain scales for assessment and understanding patient experiences to avoid undertreatment or overtreatment. The document also details nociceptive and neuropathic pain types, their origins, and the necessity of a biopsychosocial approach to pain management.

![34

Conversion tables listed an equivalent dose of fentanyl q1 hour, but they could not figure

out how this related to the fact that the fentanyl patch is changed q72h. Being unskilled in

using tables, they would not use them, fearful of making a mistake (and potentially

killing a patient). Thus, it is critical that trainees demonstrate the skills outlined above.

Ideally, the practice of such skills will occur in real life under appropriate supervision (as

is the case for other medical skills). Barring this, it is strongly recommended that trainees

practice skills such as opioid conversion using cases in groups or via self-directed

learning. Teachers may wish to make up their own cases and ask trainees to perform

certain skills (such as writing appropriate opioid orders using a conversion table), or

trainees may wish to work independently.

References

1. Good, M. et al., eds. Pain as Human Experience. 1992, University of California Press:

Berkeley, p. 1.

2. Portenoy, R. K. and P. Lesage. Management of cancer pain. Lancet 1999; 353(9165):

1695-700.

3. Bonica, J. and J. D. Loeser. Medical evaluation of the patient with pain. In: Bonica J.,

C. Chapman and W. Fordyce, eds. The Management of Pain. 1990, Lea & Febiger:

Philadelphia, pp. 563-79.

4. SUPPORT. A controlled trial to improve care for seriously ill hospitalized patients.

The study to understand prognoses and preferences for outcomes and risks of treatments

(SUPPORT). JAMA 1995; 274(20): 1591-8.

5. Won, A. et al. Correlates and management of nonmalignant pain in the nursing home.

SAGE Study Group. Systematic assessment of geriatric drug use via epidemiology. J Am

Geriatr Soc 1999; 47(8): 936-42.

6. Grossman, S.A. et al. Correlation of patient and caregiver ratings of cancer pain. J Pain

Symptom Manage 1991; 6(2): 53-7.

7. McDowell, I. and C. Newell. Measuring Health:A Guide to Rating Scales and

Questionnaires, 2nd ed. 1996, Oxford University Press: New York, pp. 355-79.

8. Weissman, D. E. and J. D. Haddox. opioid pseudoaddiction - An iatrogenic syndrome.

Pain 1989; 36(3): 363-6.

9. Twycross, R. Pain Relief in Advanced Cancer. 1994, Churchill Livingstone: London,

pp. 240, 288, 325, 353, 409-16.

10. Jenkins, C. A. and E. Bruera. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs as adjuvant

analgesics in cancer patients. Palliat Med 1999; 13(3): 183-96.

11. Hudson, N., A. Taha, et al. Famotidine for healing and maintenance in nonsteroidal

anti-inflammatory drug-associated gastroduodenal ulceration. Gastroenterology 1997;

112: 1817-22.

12. Hawkey, C. Cox-2 Inhibitors. Lancet 1999; 353: 307-14.

13. Silverstein, F. E. et al. Gastrointestinal toxicity with celecoxib vs nonsteroidal anti-

inflammatory drugs for osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis: The CLASS study: A

randomized controlled trial. Celecoxib Long-term Arthritis Safety Study. JAMA 2000;

284(10): 1247-55.

14. Porter, J. and H. Jick. Addiction rare in patients treated with narcotics [letter]. N Engl

J Med 1980; 302(2): 123.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pain-management-overview-by-muhammad-nizam-uddin-150530095409-lva1-app6892/75/Pain-Management-Overview-Muhammad-nizam-uddin-34-2048.jpg)