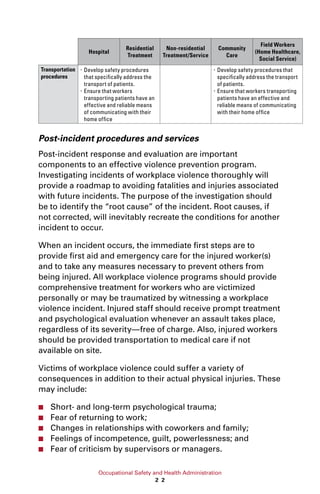

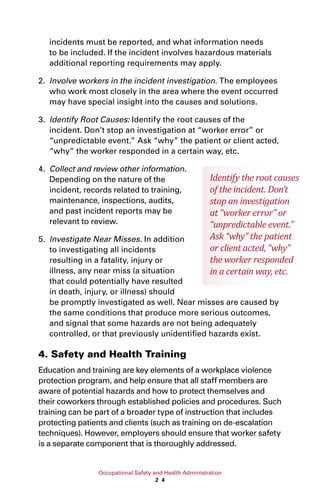

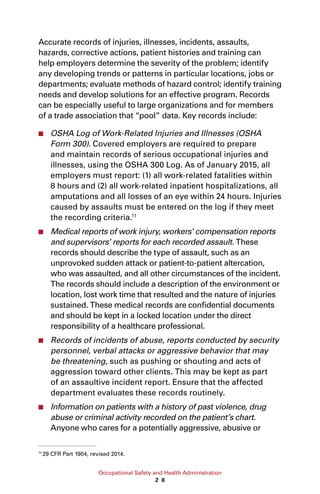

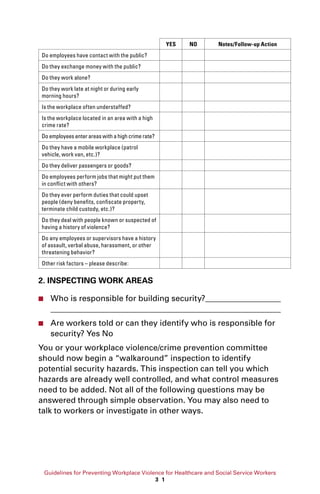

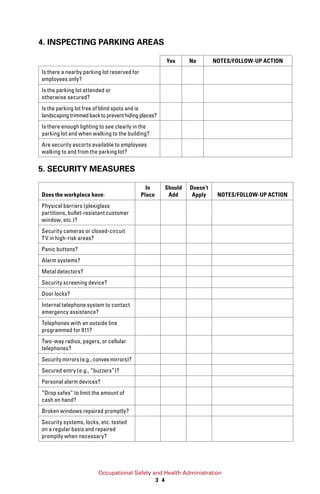

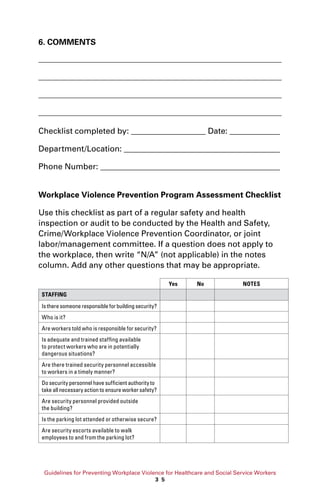

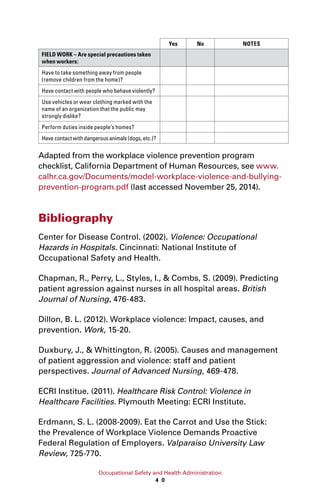

This document provides guidelines for preventing workplace violence for healthcare and social service workers. It discusses the impact of workplace violence on these workers, noting they face significant risks. The guidelines recommend developing violence prevention programs that involve management commitment, worksite analysis to identify hazards, implementing hazard prevention/control measures, safety training, and recordkeeping/evaluation. The purpose is to help employers address serious workplace violence hazards using industry best practices.