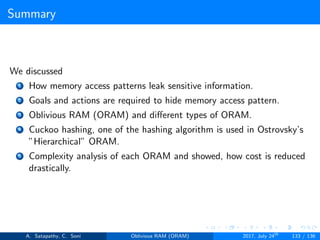

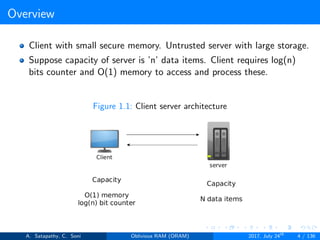

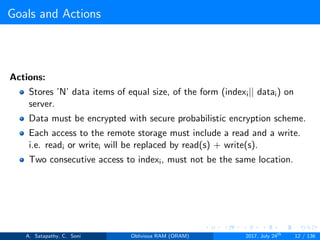

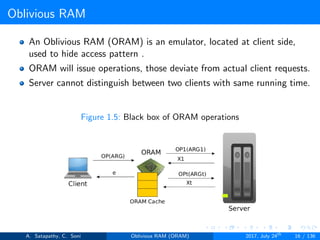

The document discusses Oblivious RAM (ORAM), a protocol designed to obscure access patterns between clients and untrusted servers while ensuring confidentiality, integrity, and privacy. Various types of ORAM are examined, including optimal, trivial, and Goldreich's square root ORAM, each addressing different trade-offs in storage and operational cost. Cuckoo hashing is also introduced as a key hashing technique used in ORAM constructions to facilitate efficient access and storage.

![Hide Access Pattern

1: function GENOME(int a, array M)

2: return M[a] Read an element of M

3: end function

Algorithm 1: Read a specific location from GNOME

1: function GENOME(int a, array M)

2: M[a] = #num Re-Write an element of M

3: return M[a]

4: end function

Algorithm 2: Update GNOME sequence

A. Satapathy, C. Soni Oblivious RAM (ORAM) 2017, July 24th

8 / 136](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/oram-180914093456/85/ORAM-8-320.jpg)

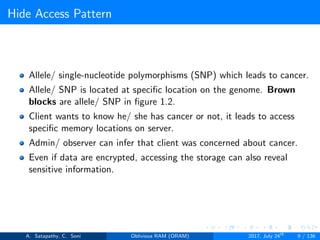

![Cuckoo Hashing

→ 20, h1(20) = 9

Table 1.3: Cuckoo hash table after insertion 20.

Table[1] 20

Table[2]

→ 50, h1(50) = 6

Table 1.4: Cuckoo hash table after insertion 50.

Table[1] 50 20

Table[2]

A. Satapathy, C. Soni Oblivious RAM (ORAM) 2017, July 24th

20 / 136](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/oram-180914093456/85/ORAM-20-320.jpg)

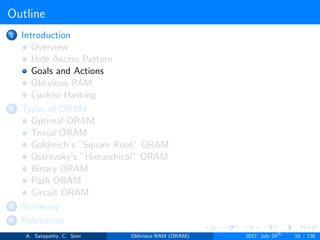

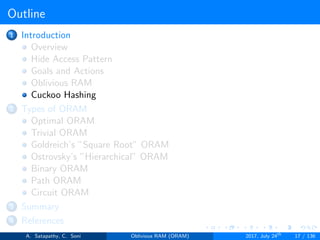

![Cuckoo Hashing

→ 53, h1(53) = 9, but 20 at 9. So, h2(20) = 1.

Table 1.5: Cuckoo hash table after insertion 53.

Table[1] 50 53

Table[2] 20

→ 75, h1(75) = 9, h2(53) = 4

Table 1.6: Cuckoo hash table after insertion 75.

Table[1] 50 75

Table[2] 20 53

A. Satapathy, C. Soni Oblivious RAM (ORAM) 2017, July 24th

21 / 136](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/oram-180914093456/85/ORAM-21-320.jpg)

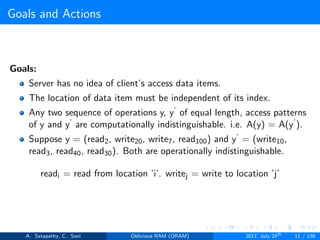

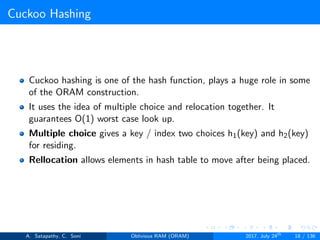

![Cuckoo Hashing

→ 100, h1(100) = 1.

Table 1.7: Cuckoo hash table after insertion 100.

Table[1] 100 50 75

Table[2] 20 53

→ 67, h1(67) = 1, h2(100) = 9.

Table 1.8: Cuckoo hash table after insertion 67.

Table[1] 67 50 75

Table[2] 20 53 100

A. Satapathy, C. Soni Oblivious RAM (ORAM) 2017, July 24th

22 / 136](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/oram-180914093456/85/ORAM-22-320.jpg)

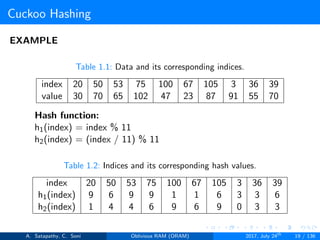

![Cuckoo Hashing

→ 105, h1(105) = 6, h2(50) = 4, h1(53) = 9, h2(75) = 6.

Table 1.9: Cuckoo hash table after insertion 105.

Table[1] 67 105 53

Table[2] 20 50 75 100

→ 3, h1(3) = 3.

Table 1.10: Cuckoo hash table after insertion 3.

Table[1] 67 3 105 53

Table[2] 20 50 75 100

A. Satapathy, C. Soni Oblivious RAM (ORAM) 2017, July 24th

23 / 136](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/oram-180914093456/85/ORAM-23-320.jpg)

![Cuckoo Hashing

→ 36, h1(36) = 3, h2(3) = 0.

Table 1.11: Cuckoo hash table after insertion 36.

Table[1] 67 36 105 53

Table[2] 3 20 50 75 100

→ 39, h1(36) = 6, h2(105) = 9, h1(100) = 1, h2(67) = 6, h1(75) = 9,

h2(53) = 4, h1(50) = 6, h2(39) = 3.

Table 1.12: Cuckoo hash table after insertion 39.

Table[1] 100 36 50 75

Table[2] 3 20 39 53 67 105

A. Satapathy, C. Soni Oblivious RAM (ORAM) 2017, July 24th

24 / 136](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/oram-180914093456/85/ORAM-24-320.jpg)

![Cuckoo Hashing

Table 1.13: Final hash table

Table[1] 100 36 50 75

Table[2] 3 20 39 53 67 105

Time complexity; Insertion - O(1). Deletion - O(1).

If collision occurs using two exist hash functions, new hash functions

are selected. Continue the cycle, until all data are placed

A. Satapathy, C. Soni Oblivious RAM (ORAM) 2017, July 24th

25 / 136](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/oram-180914093456/85/ORAM-25-320.jpg)

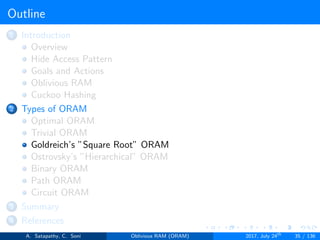

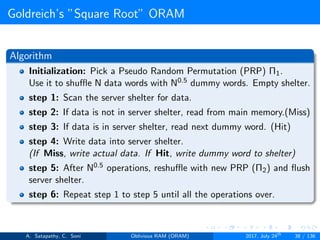

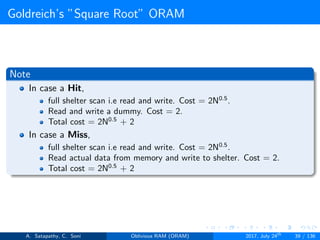

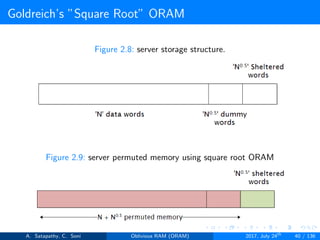

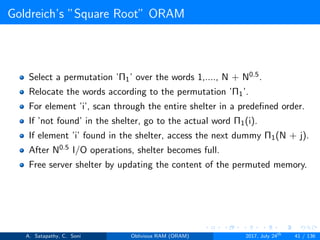

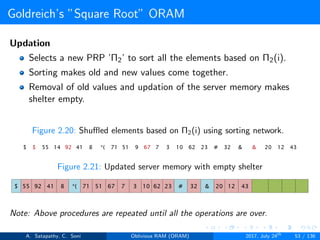

![Goldreich’s ”Square Root” ORAM

Goldreich’s square root ORAM requires

Server storage N + 2C words

Client storage O(1) [Constant data words]

’N’ actual data words, ’C’ dummy words and ’C’ sheltered words

Figure 2.6: server storage structure in square root ORAM

A. Satapathy, C. Soni Oblivious RAM (ORAM) 2017, July 24th

36 / 136](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/oram-180914093456/85/ORAM-36-320.jpg)

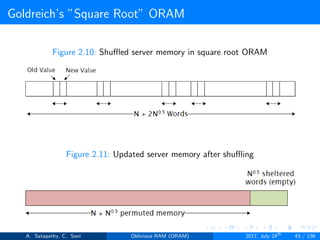

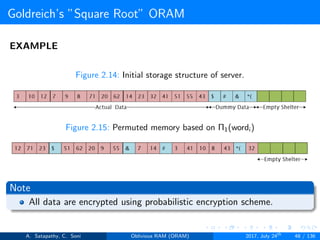

![Goldreich’s ”Square Root” ORAM

Generally, in Goldreich’s square root ORAM, C = N0.5

Server storage N + 2N0.5 words

Client storage O(1) [Constant data words]

’N’ actual data words, ’N0.5’ dummy words and ’N0.5’ sheltered words

Figure 2.7: server storage structure in square root ORAM

A. Satapathy, C. Soni Oblivious RAM (ORAM) 2017, July 24th

37 / 136](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/oram-180914093456/85/ORAM-37-320.jpg)

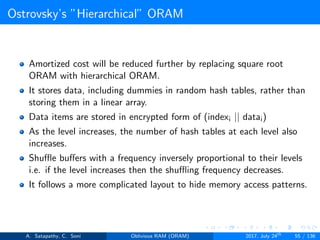

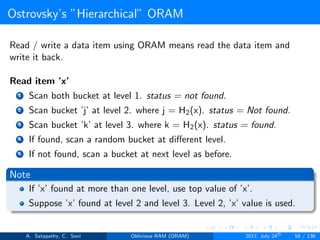

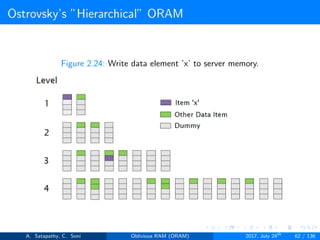

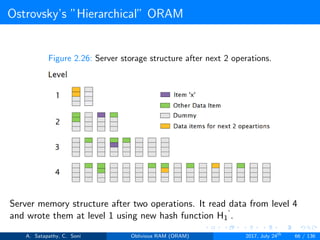

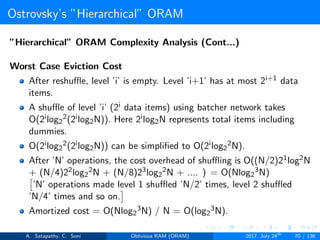

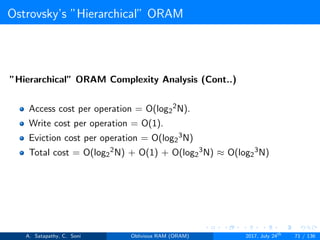

![Ostrovsky’s ”Hierarchical” ORAM

Client Storage

Hash function for each level.

O(1) client memory. [Constant data words].

Server Storage

log2N levels for ’N’ data items.

Level ’i’ contains 2i hash tables or buckets.

Each hash table contains log2N blocks.

Each block contains encrypted data or dummy item.

Level ’i’ contains at most 2i data items.

Item ’x’ is located in one of the levels, in buckets Hi(x). (i is the level,

x is index of the item)

A. Satapathy, C. Soni Oblivious RAM (ORAM) 2017, July 24th

56 / 136](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/oram-180914093456/85/ORAM-56-320.jpg)

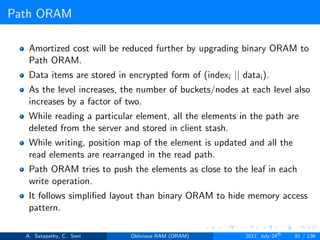

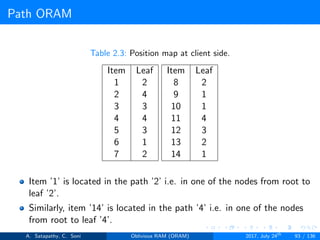

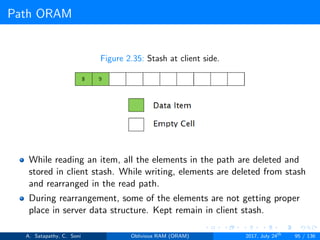

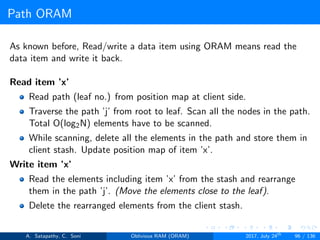

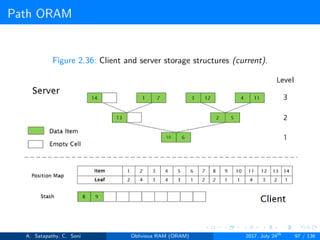

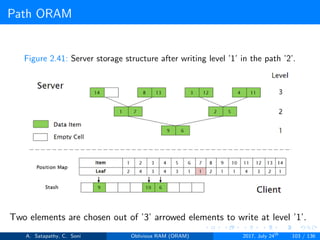

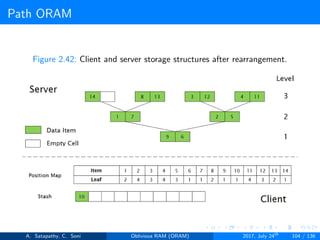

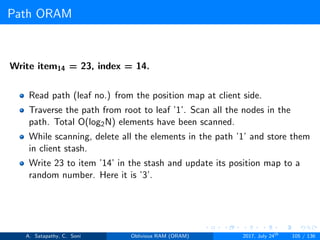

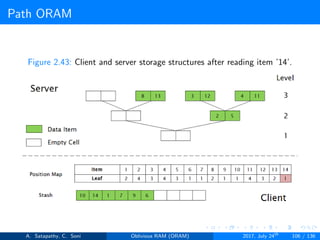

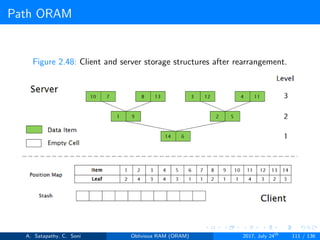

![Path ORAM

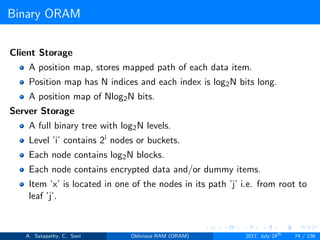

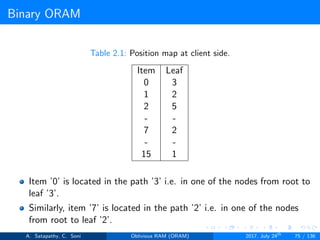

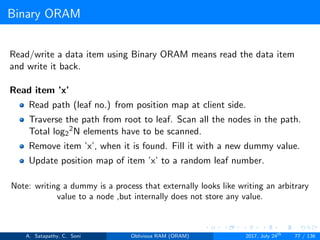

Client Storage

A position map, stores mapped path of each data item.

Position map has N indices, but each index is log2N bits long.

A position map of Nlog2N bits.

A stash (temporary storage) where size of stash is bounded by

Pr[stash = R] ≥ 1 - 2-Ω(R). R = O(log2N).ω(1).

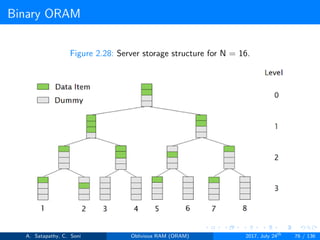

Server Storage

A full binary treee with log2N levels.

Each node contains O(1) blocks.

As level increases, number of nodes increases by a factor of two.

Block in each node either contains encrypted data item or it’s empty.

item ’x’ is located in one of the nodes in its path ’j’ i.e. from root to

leaf ’j’.

A. Satapathy, C. Soni Oblivious RAM (ORAM) 2017, July 24th

92 / 136](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/oram-180914093456/85/ORAM-92-320.jpg)

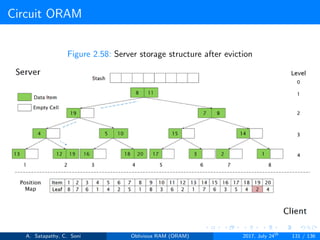

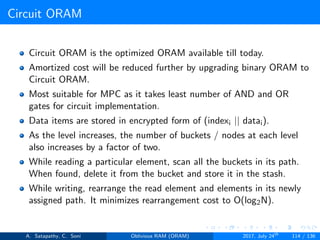

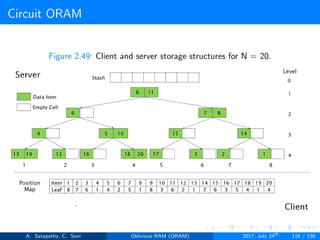

![Circuit ORAM

Client Storage

A position map, stores mapped path of each data item.

Position map has N indices, but each index is log2N bits long.

A position map of Nlog2N bits.

Server Storage

A full binary tree with log2N levels.

Each node contains O(1) blocks.

As level increases, number of nodes increases by a factor of two.

Block in each node either contains encrypted data item or it’s empty.

Item ’x’ is located in one of the nodes in its path ’j’ i.e. from root to

leaf ’j’.

A stash (temporary storage) where size of stash is bounded by

Pr[stash = R] ≥ 1 - 2-Ω(R). R = O(log2N).ω(1).

A. Satapathy, C. Soni Oblivious RAM (ORAM) 2017, July 24th

115 / 136](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/oram-180914093456/85/ORAM-115-320.jpg)

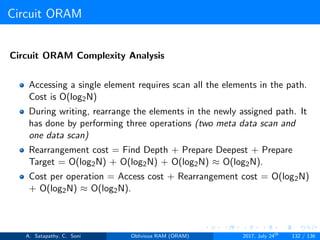

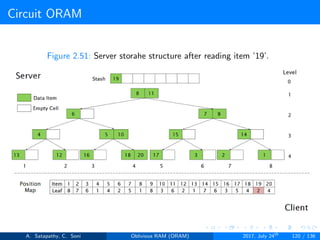

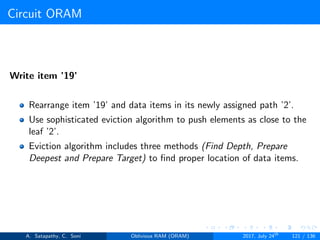

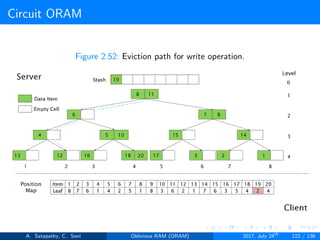

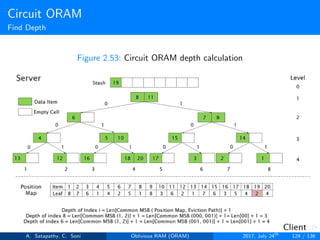

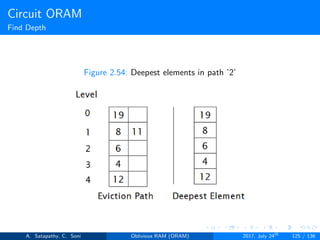

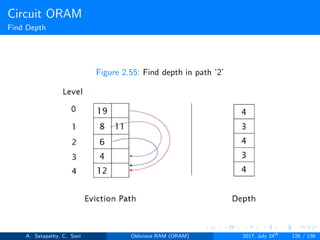

![Circuit ORAM

As eviction is performed after each read operation, find deepest element to

be evicted, at each level in the path. Eviction in a path includes

Find Depth (s → t): It is the top-down proceduce. A block in

node[s] can legally reside in node[t]; but no block in node[s] can

legally reside in node[t+1...L]. Here s < t.

Prepare Deepest (s → t): It is the bottom-up procedure. The

deepest block in node[0...s-1] that can legally reside in node[s]

currently resides in node[t]. Here t < s.

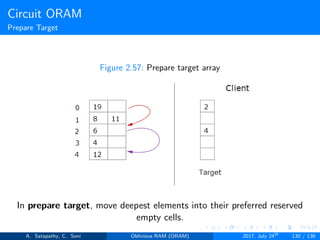

Prepare Target (s → t): It follows top-down approach. During the

real block scan, pick up the deepest block in node[s] and drop it in

node[t]. Here s < t.

A. Satapathy, C. Soni Oblivious RAM (ORAM) 2017, July 24th

123 / 136](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/oram-180914093456/85/ORAM-123-320.jpg)

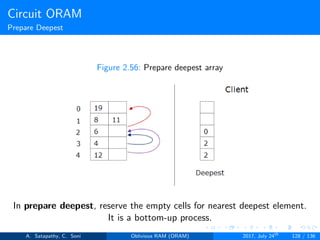

![Circuit ORAM

Prepare Deepest

1: function PREPARE DEEPEST(int Depth[ ])

2: Initialize Deepest := (⊥,⊥, ..., ⊥), src := ⊥, goal := -1.

3: If stash not empty then src := 0, goal := Depth[0]

4: end if

5: for i = 1 to L do:

6: if goal ≥ i then Deepest[i] : = src

7: end if

8: l := Deepest[i]

9: if l > goal then goal := l, Src := i

10: end if

11: end for

12: end function

Algorithm 3: Prepare deepest array.

A. Satapathy, C. Soni Oblivious RAM (ORAM) 2017, July 24th

127 / 136](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/oram-180914093456/85/ORAM-127-320.jpg)

![Circuit ORAM

Prepare Target

1: function PREPARE TARGET(int Deepest[ ])

2: Initialize dest := ⊥, src := ⊥, Target := (⊥,⊥,...,⊥)

3: for i = L down to 0 do:

4: if i == src then Target[i] := dest, dest := ⊥, src := ⊥.

5: end if

6: if ((dest = ⊥ and node[i] has empty slot) or (Target[i] =

⊥)) and (Deepest[i] = ⊥) then

7: src := Deepest[i], dest := i

8: end if

9: end for

10: end function

Algorithm 4: Prepare target array.

A. Satapathy, C. Soni Oblivious RAM (ORAM) 2017, July 24th

129 / 136](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/oram-180914093456/85/ORAM-129-320.jpg)