This document dwells into the Various methods used for optimization of fermentation process and their applications in food industry.

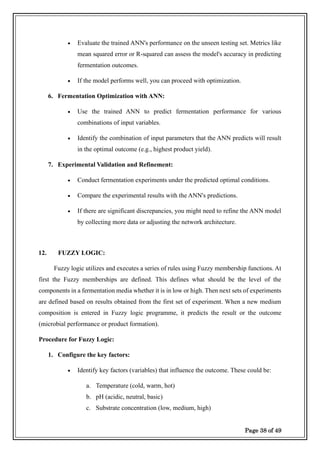

Fermentation optimization is a cornerstone of efficient and scalable bioproduction. It

involves meticulously fine-tuning various process parameters to create an ideal environment

for the target microorganisms. This translates to maximizing desired outputs, such as product

titer and yield, while ensuring process robustness and cost-effectiveness. The ultimate goal is

to create an optimal environment for the target microorganisms, allowing them to thrive and

produce the target molecule at the highest possible rate and concentration (titre) while

minimizing production costs and ensuring consistent product quality. This optimization process

is crucial across various industries that rely on fermentation, including: Optimizing

fermentation for beer, yogurt, or cheese production can enhance flavour profiles, improve

texture, and increase yield, Fine-tuning fermentation processes for bioethanol or biodiesel can

significantly impact production efficiency and fuel quality and optimizing fermentation for

antibiotics or other drugs can maximize yield, reduce production time, and ensure consistent

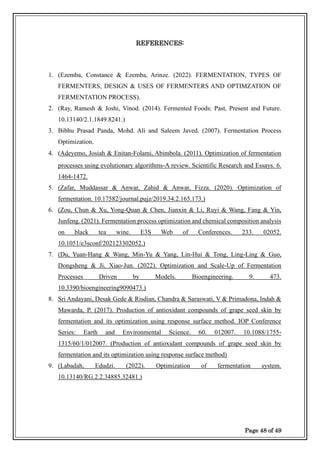

drug potency. Many optimization techniques are available for optimization of fermentation

medium and fermentation process conditions such as

✓One-factor-at-a-time.

✓ Borrowing.

✓ Component replacing.

✓ Biological Mimicry

✓ Factorial Design.

✓ Placket and Burmar’s Design.

✓ Central composite Design.

✓ Response Surface methodology.

✓ Evolutionary operation.

✓ Evolutionary operation factorial design.

✓ Artificial neural network.

✓ Fuzzy logic.

✓ Genetic Algorithms

Each

optimization technique has its own advantages and disadvantages.