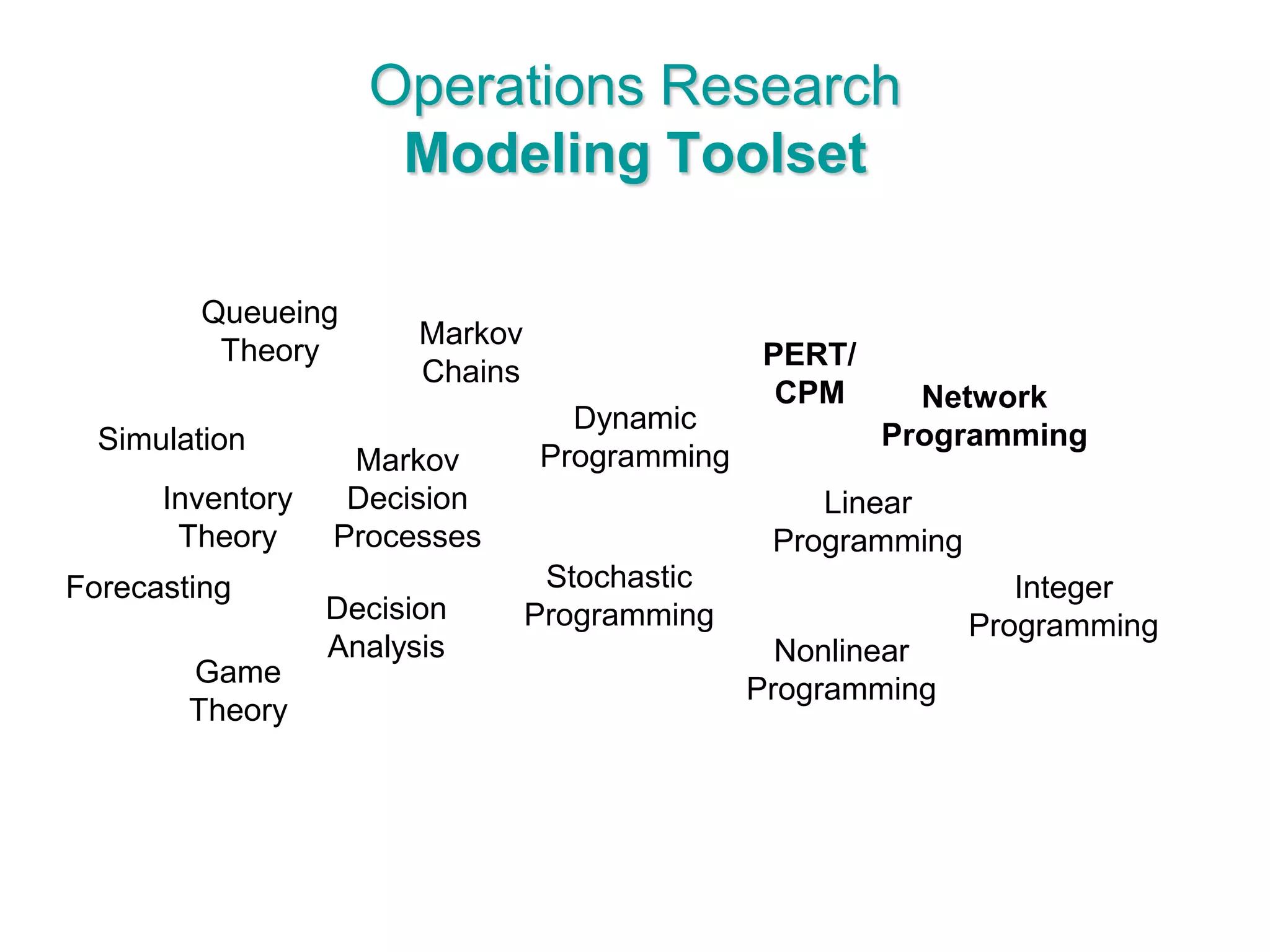

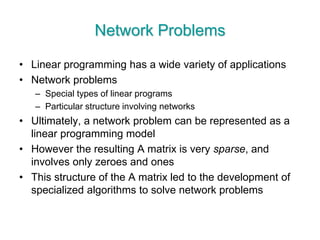

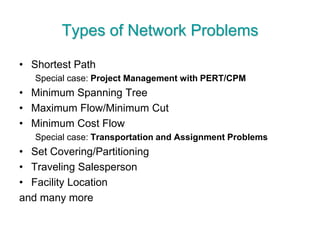

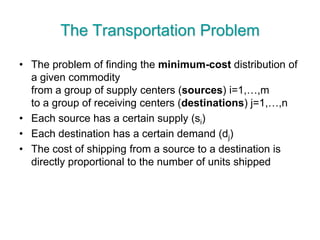

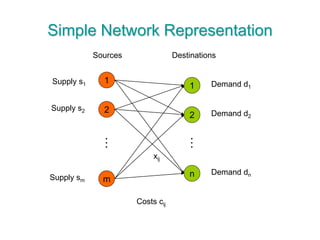

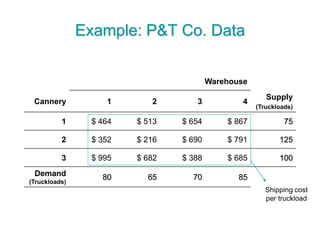

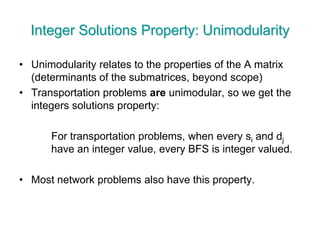

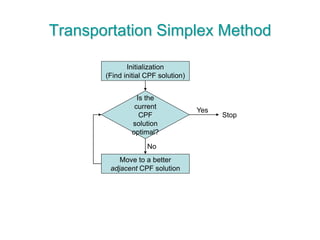

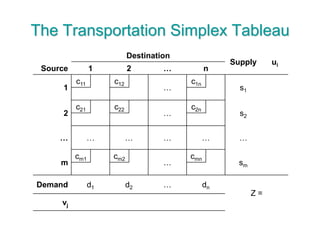

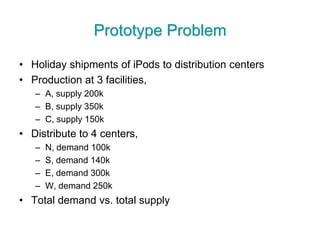

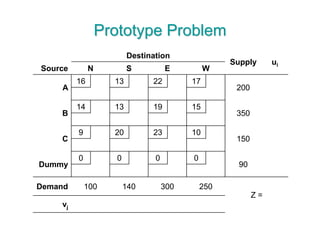

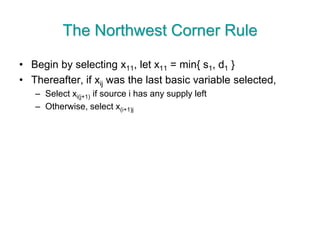

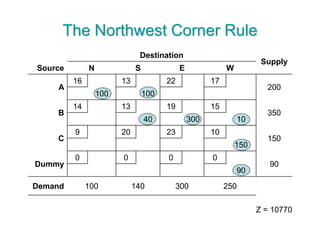

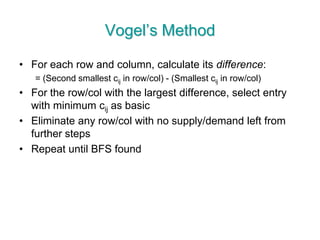

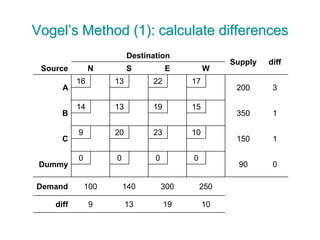

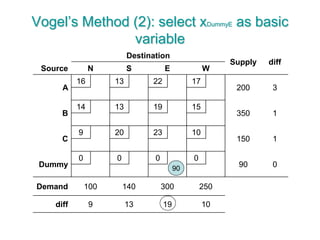

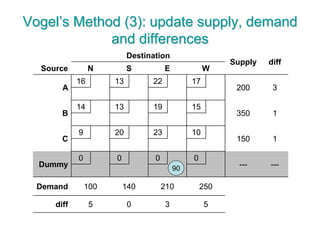

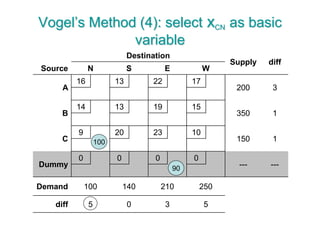

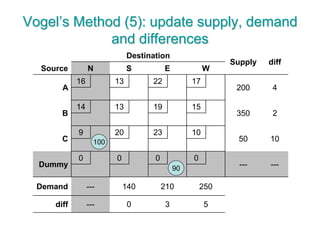

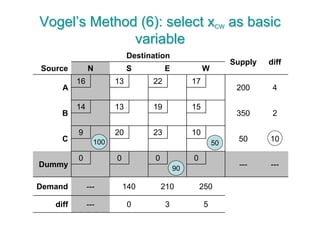

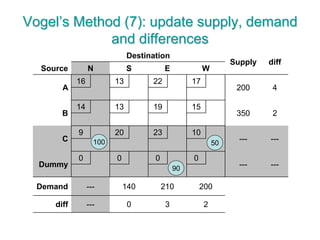

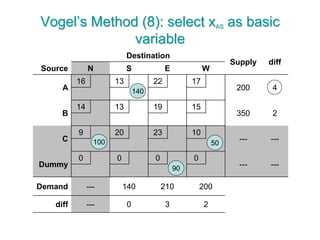

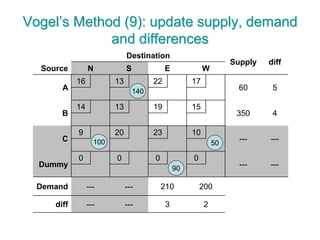

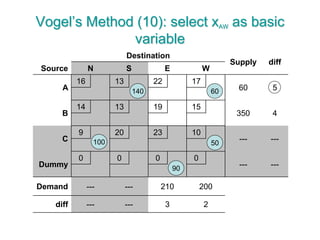

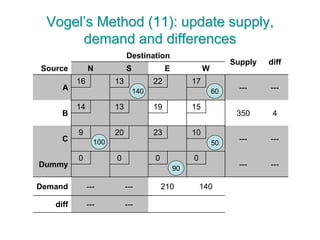

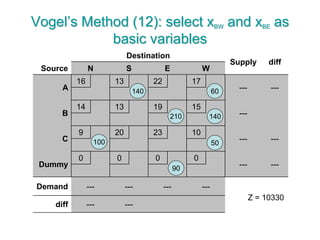

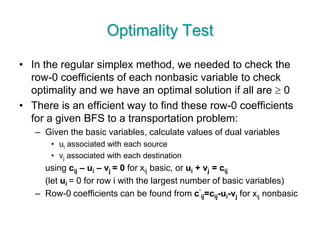

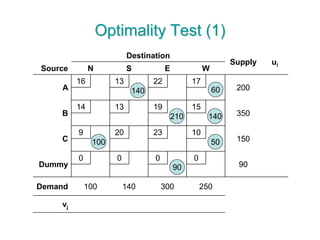

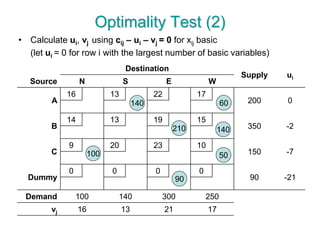

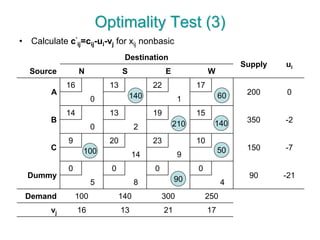

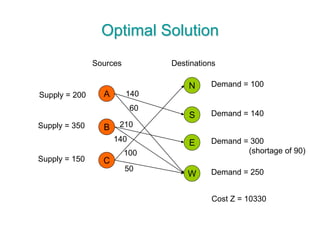

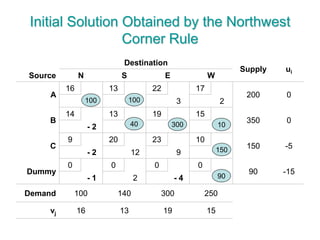

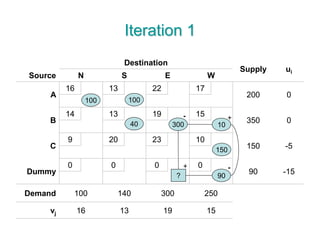

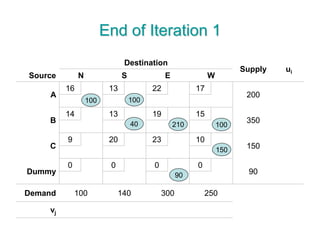

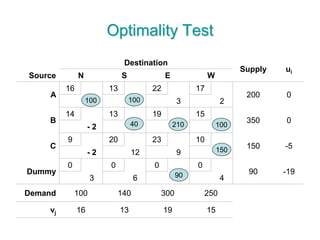

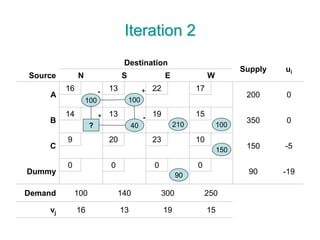

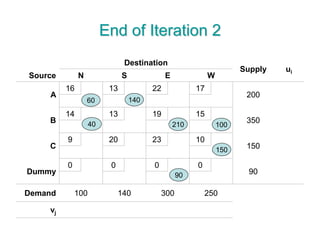

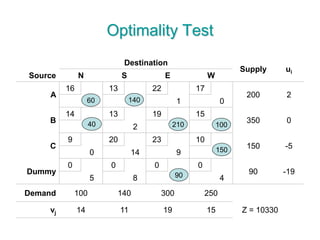

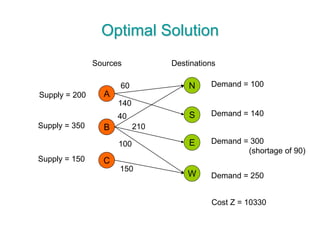

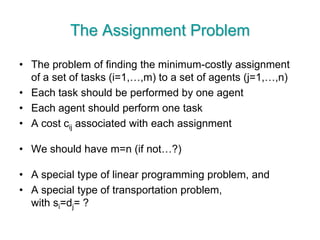

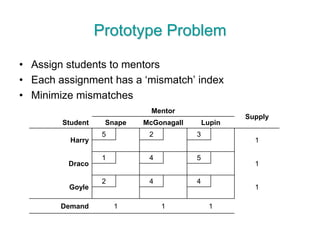

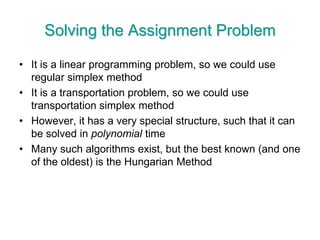

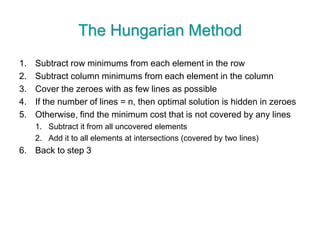

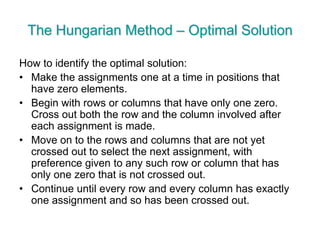

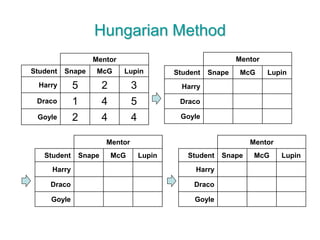

The document discusses operations research modeling tools, particularly focusing on linear programming and its application to network problems, including transportation and assignment problems. It explains the transportation problem, which aims to minimize distribution costs while satisfying supply and demand constraints, and introduces the transportation simplex method for finding optimal solutions. Several methods for finding initial basic feasible solutions, as well as optimization techniques within the context of transportation, are also outlined.