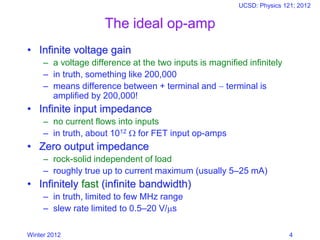

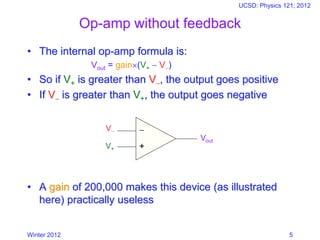

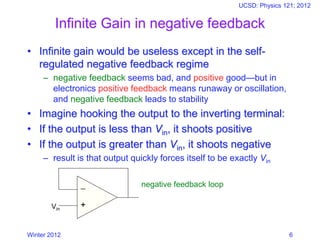

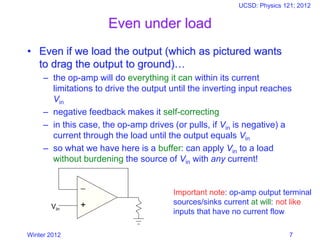

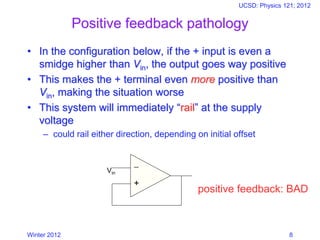

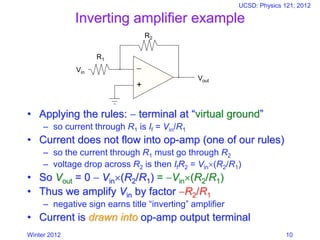

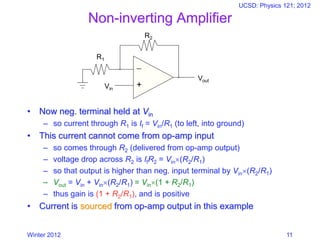

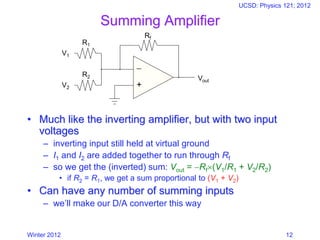

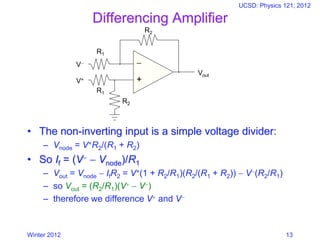

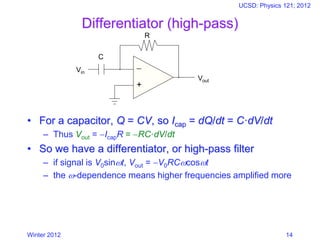

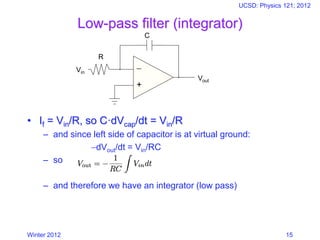

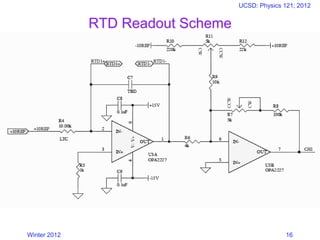

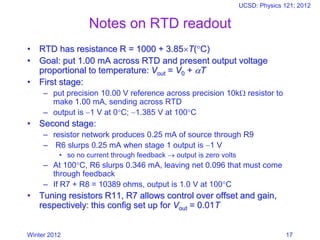

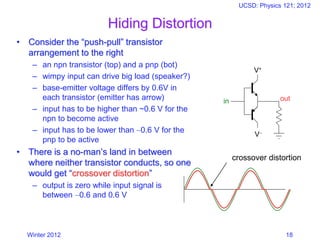

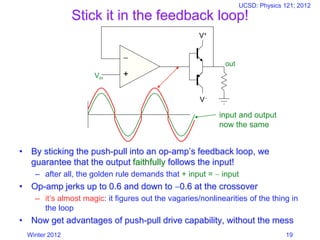

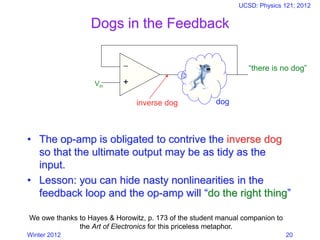

This document provides an introduction and overview of operational amplifiers (op-amps). It discusses the key characteristics of op-amps including their symbol, inputs and outputs. It then explains how op-amps work in negative feedback configurations to achieve high gain and voltage regulation. Several common op-amp circuit configurations are presented such as inverting amplifiers, non-inverting amplifiers and summing amplifiers. Examples of applications like temperature sensors and active filters are also covered. The document emphasizes that op-amps in negative feedback will regulate their output to match the difference between their input terminals.