This manual provides a comprehensive overview of netcasting, focusing on webcasting and podcasting, aimed at non-technical businesspeople. It explains what netcasting is, its historical context, and its evolution, stresses the difference between webcasting and podcasting, and offers practical steps to create your first podcast. Additional resources, a glossary, and a cost model are included to support further learning and understanding.

![Sample Podcasts

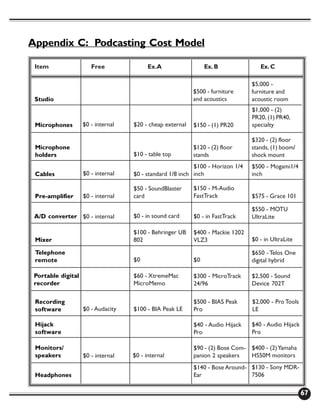

To find the following podcasts, launch iTunes software and search the iTunes Music Store (Section 3.1).

WGBH Morning Stories [audio]

Unforgettable stories from everyday people.

MAKE Magazine [video]

Phillip Torrone hosts the MakeZine.com audio show for MAKE magazine fans. MAKE is a

quarterly publication from O’Reilly for those who just can’t stop tinkering, disassembling, re-

creating, and inventing cool new uses for the technology in our lives. It’s the first do-it-yourself

magazine dedicated to the incorrigible and chronically incurable technology enthusiast in all of

us. MAKE celebrates your right to tweak, hack, and bend technology any way you want.

This WEEK in TECH (twit) [audio, video]

Your first podcast of the week is the last word in tech. Join Leo Laporte, Patrick Norton, John C.

Dvorak, and other luminaries in a roundtable discussion of the latest trends in high tech. Winner

of “People’s Choice Podcast” and “Best Technology Podcast” in the 2005 People’s Choice

Podcast Awards. Released every Sunday at midnight, Pacific time zone.

American Public Media Marketplace [audio]

American Public Media’s Marketplace is public radio’s daily magazine on business and

economics news for the rest of us. Each day, host Kai Ryssdal and guests bring you the best in

business news from wallet to Wall Street. The Marketplace podcast is updated Monday through

Friday.

iTunes New Music Tuesday [enhanced audio]

New Music Weekly is your guided tour through the best new music iTunes has to offer. From

brand new releases, exclusives, pre-releases, iTunes Originals, and catalog albums just added,

there are thousands of tracks in the store every single week. Navigate through the abundance of

music to find the hottest new tracks and the hidden gems every week.

Marketing Edge [audio]

The original marketing podcast. Thoughtful commentary, advice and insight on marketing, public

relations, podcasting and communication from Albert Maruggi, a veteran of radio, television,

politics and the corporate world.

The Podcast Academy [audio]

A channel from GigaVox Media, brings you recordings of Podcast Academy event speakers.

Updates are provided on technology, technique, and podcast industry insights.

57](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/netcastingmanual-120126071812-phpapp01/85/Netcasting-Manual-58-320.jpg)