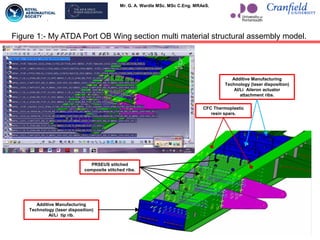

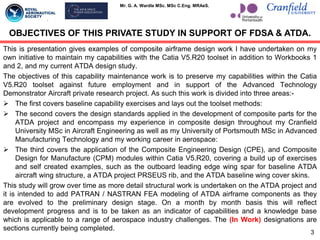

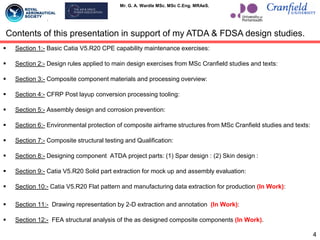

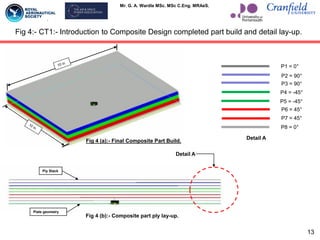

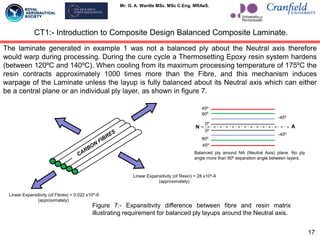

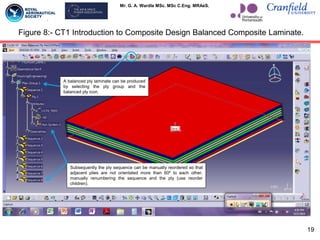

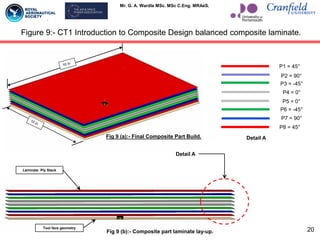

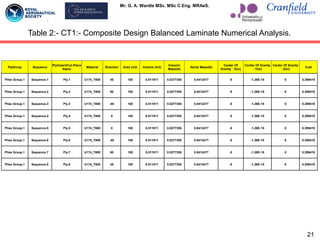

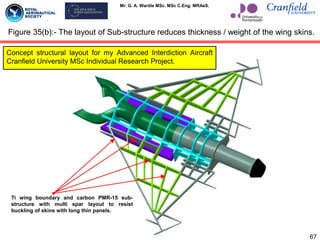

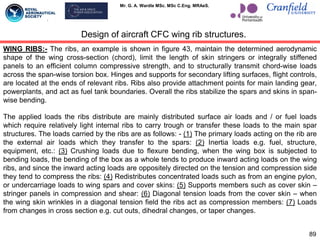

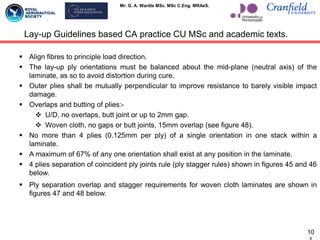

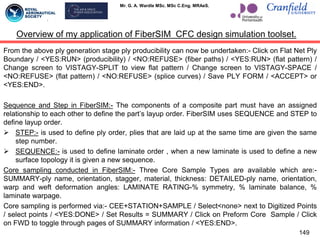

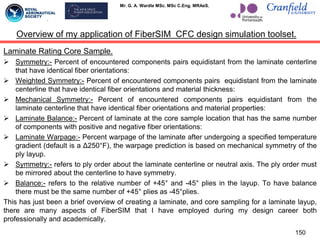

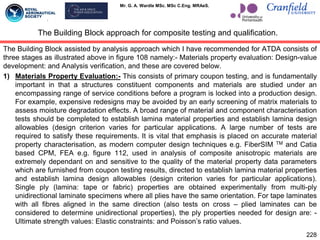

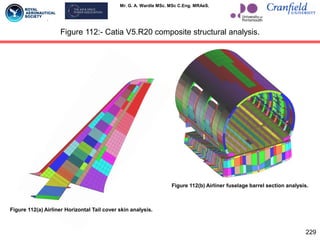

This document outlines Mr. G. A. Wardle's studies on airframe composite design, showcasing his work with the CATIA V5 R20 toolset to maintain and enhance his capabilities in aerospace engineering. The study is divided into sections covering baseline capabilities, design standards, and practical applications of composite engineering modules, alongside detailed methodologies for creating composite laminates. The ongoing research is aimed at supporting the Advanced Technology Demonstrator Aircraft project and reflects the development progress in composite materials and design techniques.

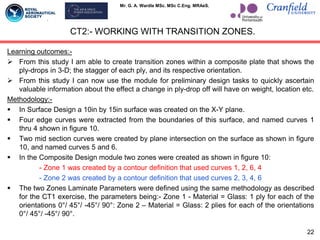

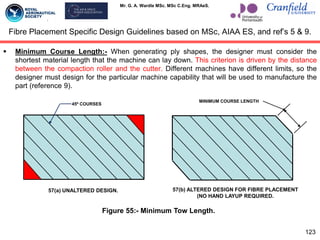

![Mr. G. A. Wardle MSc. MSc C.Eng. MRAeS.

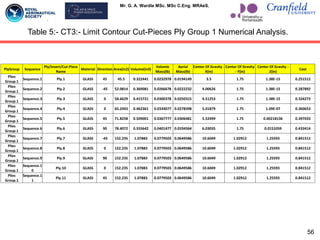

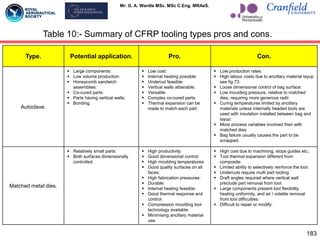

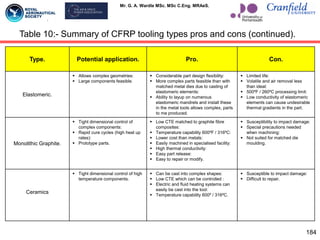

Properties

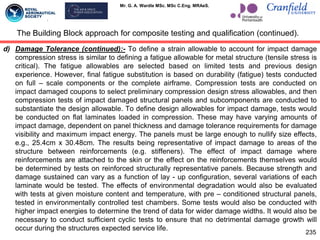

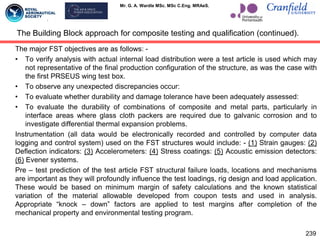

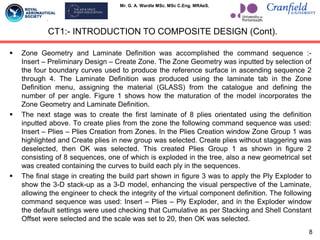

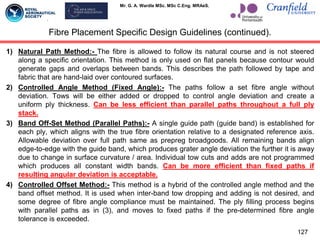

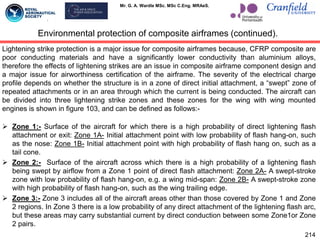

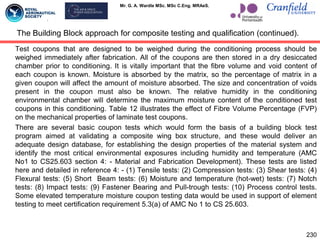

Effect of FVP on laminate mechanical properties.

0ºnt 90ºnt ±45ºns [(±45º)5/0º16/90º4]c

Ultimate strength

Varies directly

with FVP

Not sensitive to

FVP

Varies directly

with FVP

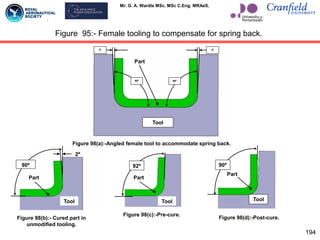

Varies directly

with FVP

Ultimate strain

Not sensitive to

FVP

Not sensitive to

FVP

Not sensitive to

FVP

Not sensitive to

FVP

Proportionality

limit stress

Varies directly

with FVP

Not sensitive to

FVP

Varies directly

with FVP

Varies directly

with FVP

Proportionality

limit strain

Varies directly

with FVP

Not sensitive to

FVP

Varies directly

with FVP

Varies directly

with FVP

Poisson‟s ratio

Not sensitive to

FVP

Not sensitive to

FVP

Varies directly

with FVP

Not sensitive to

FVP

Modulus of

elasticity

Varies directly

with FVP

Varies directly

with FVP

Varies directly

with FVP

Varies directly

with FVP

231

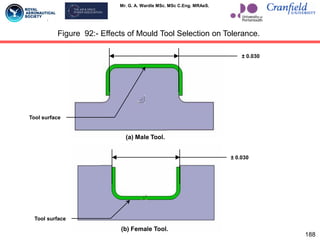

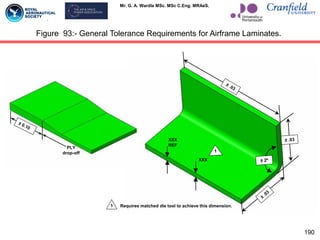

Table 12:- Effect of Fibre Volume Percentage (FVP) on laminate mechanical properties.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/myairframecompositedesigncapabilitystudies-240624105336-ff711ea0/85/My-Airframe-Composite-Design-Capability-Studies-pdf-231-320.jpg)